“I feel like people talk faster than they usually do on screen, and I don’t understand why, when somebody asks you if you want a cup of coffee, you can’t just say yes or no. Why do you have to have four expressions, and then look and think? You don’t. You know if you want coffee, or if you don’t want coffee.”

—AMY SHERMAN-PALLADINO WRITER/CREATOR/SHOWRUNNER/DIRECTOR GILMORE GIRLS, THE MARVELOUS MRS. MAISEL

Chapter 10

Writing Smart Dialogue in the Digital Era

There are plenty of books on screenwriting out there that talk about the importance of sharp, crackling dialogue. Since I’m going to be discussing both TV comedy and drama, I’ll present dialogue examples from each as I cover practical exercises and core skills to develop in our toolboxes as television writers.

The Oblique

One of the most frequent notes on beginning screenwriters’ scripts is that the dialogue is “OTN,” or “on the nose.” Although it’s my belief that the best dialogue is oblique, often with my own writing, I’ll first write the scene on the nose as an exercise, writing just the bare facts of what every character would say if they were to speak exactly what their truth is. Sometimes we can do that in outline, including quotes where the characters say what they feel and what their needs are directly. Then, go back and dig in. Digging in is asking ourselves, “Based on the chemistry of these characters, and based on the specific circumstances of this scene, knowing where each character came from and where each character is going after this scene, what’s the character’s mood? Where is he or she emotionally?” Based on those factors, a lot of what characters might actually say in the scene gets subverted. They’re not really speaking their truth, but rather, their words are influenced by many factors that may have nothing to do with the person that they’re talking to in the scene. It could be that they had a bad day at the office and they just came from an argument with a co-worker, and now they’re in a scene with a person who they have no problem with, but that tension is carried over. So tracking—both logistical and emotional—is a key component in how we approach dialogue. Where are characters coming from, where are they going to and, when they meet in a scene, what is the main focus of the action? Are they going to speak their truth, or are they going to couch it in softer terms? Are they going to project things into the scene that have nothing to do with the actual dynamics of it?

Secondly, it’s important to realize that dialogue is not real speech. Meaning that, even in the most realistic, grounded, gritty series such as HBO’s critically acclaimed The Wire, where people do speak in ways that sound very natural and faithful to who they are as characters, the dialogue is heightened. There’s poetry in the words. The writers not only played around with how the more educated, erudite characters speak, but they also gave disenfranchised characters a specific slang that’s their own private language. Speaking to a class at UCLA recently, creator David Simon said that the vernacular used among the “corner boys” was a by-product of his own years sitting out on a West Baltimore corner. He also said that he would not attempt to write The Wire set in today’s Baltimore because the language on the streets, in his view, has changed completely.

Whether a character talks a lot or a little depends on who they are. Some characters are laconic—men and women of few words. Others are chatterboxes, speak in huge volumes of words, and it becomes part of who they are as characters. Take Jimmy McGill in Better Call Saul: His words are both his defense and his weapon, and he uses them to manipulate people. They’re also what he gets his strength from. Jimmy (a/k/a Saul Goodman, played by Bob Odenkirk) is a wordsmith. The way he plays people and his expertise in the courtroom come from his natural talent for and relationship to language. Other characters in the show, such as Mike Ehrmantraut (Jonathan Banks), are constricted because they can’t ever quite find the right words. Even if they’re very powerful and have a dynamic internal life, when they have to speak and make connections with other people, they find themselves frightened about it. It’s the power of Mike’s character to choose to stay silent when he wants.

Bonus Content

Bonus Content

Mike Ehrmantraut and The Profound Power of Silence, plus script excerpt from Better Call Saul at www.routledge.com/cw/landau.

Idiosyncratic Voices: Empire, Silicon Valley

Related to the idea that dialogue is not real speech is the fact that every character needs to have a distinctive voice. Your real-life friends may all speak in a similar way, but one of the tools that we use to differentiate between each character is to give each of them a different cadence, vocabulary and approach in terms of how he or she sees the world and relates to other people. The more we can create distinctive voices, the more the dialogue will pop off the page. It’s a good exercise, after writing a scene, to cover the name of the character and just read the dialogue without knowing who’s saying what. We—and anyone who’s reading—should be able to identify the character just based on how the characters are drawn. If the lines of dialogue are interchangeable, it means they’re not idiosyncratic enough. Maybe we don’t know our characters well enough yet. That’s when it’s time to go back and layer it and write things that only one character would say, and things that only another character would say, so that the audience can really get their unique personalities, their relationship to language and how they communicate with other people.

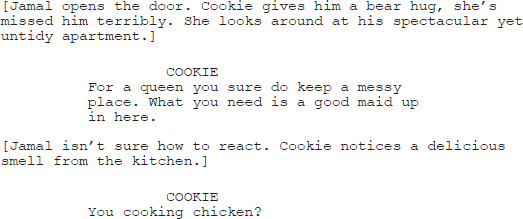

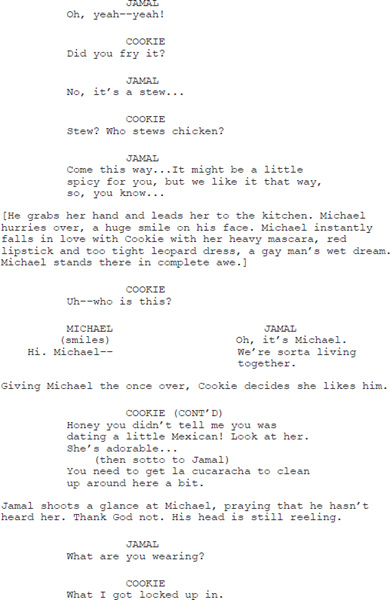

Empire features an ensemble cast of characters who each have very distinctive voices, particularly the character of Cookie (Taraji P. Henson). Cookie has her own way of looking at the world, her own sense of entitlement and her own view of right and wrong. She has her own language in how she talks to people, how she uses her sexuality, her feminine wiles and maternal persuasion in certain situations. She’s a diplomat when it’s called for, but she’s also a person who you do not want to cross, because if you get on her bad side, it’s not going to go well for you. Cookie’s spent time in prison, has got street smarts and, now, even though she has money and power, and dresses the part, she is somebody to underestimate at one’s own peril. In the pilot, she gets out of jail and goes to see her son Jamal (Jussie Smollett) who she knows is gay, but he thinks she’s completely in the dark about it. He’s at home with his boyfriend Michael (Rafael de la Fuente), and as soon as Cookie’s outside, they try to take away any signs in their apartment that would reveal that they’re a couple. They’re self-conscious and afraid of what Cookie’s going to think of them. But she breezes in, and it’s almost immediately dispelled in a fresh, unique way.

In terms of distinctive voices, also check out the pilot episode of Silicon Valley. In the teaser, a nerdy venture capitalist speaks at an event at a McMansion where Kid Rock is the entertainment. The guy tries to be cool, but his speech is chock full of Silicon Valley techno jargon. All of the main characters dress, relate to and interact with each other in a certain way—as techno-nerds. The scene speaks volumes about who they are, without having to see them in some kind of prologue that showed us how they got to this point. They don’t need to explain the jargon; they just speak that way. Some people, such as my stepson, who is a computer genius, understand everything they’re saying about algorithms or what have you. I have no idea what they’re saying, but I know that it must mean something. What’s important is that I know it’s important to them and that they know what it means. And so they create their own private language.

Get in Late, Get Out Early

When writing scenes, try to start in the middle and get out before they end. A general rule of thumb is, after finishing the script, go back and look at every scene. Cut the first two and last two lines, and the scene will almost always be better. One of our instruments in the toolbox of dialogue writing is telling the story “in the cut”—what we cut from and to in the next scene actually creates momentum and narrative drive. Unless we’re writing a multi-camera sitcom, we want to be able to cut away from a scene and don’t need to have characters entering and exiting spaces. That’s often repetitive. They can be walking and talking, but it doesn’t have to start at the very beginning of a conversation. Just drop us in and have things already in motion. It creates momentum in the script.

Verbal and Non-Verbal Communication

Bear in mind that when we talk about communication, and we talk about dialogue, in general, about 7% of communication is actual words. There are statistics that say that 38% is vocal elements, such as the tone and pitch of someone’s voice—are they agitated, happy, fearful etc.—and the other 55% is non-verbal. Non-verbal communication includes facial expressions, gestures and posture. So 93% of our communication is non-verbal. If somebody is leaning back with their arms crossed and we ask, “Are you mad at me?” he/she might say, “No, I’m not mad at you at all,” but their words are in opposition to the truth. And the truth often will come out through body language and through lack of eye contact. How we behave and our actions, speak louder than words.

Originally, television had its roots in theater, so early television was just that: theatrical. Characters often made obvious, declarative statements about their thoughts and feelings. The idea was that the TV screen was like a proscenium arch, and all the action would occur within that frame. Later, as TV evolved, it became all about close-ups. In daytime and nighttime soap operas such as Peyton Place and Marcus Welby, M.D., the writers were cognizant that TV cameras offered a sense of intimacy by being able to get in extremely close on the actors’ faces. That was something new, an added bonus that audiences couldn’t get in the theater.

Today, as television has continued to advance, and our TV screens have increased in quality, television has become more cinematic—to the point where many shows, for instance, Game of Thrones, are as cinematic as any epic, wide-screen movie. Now, it could almost be a criticism for some single-camera and one-hour dramas, that they’re too claustrophobic. On shows such as Orange Is the New Black, which takes place in an inherently claustrophobic environment, creator Jenji Kohan is always trying to find ways to get them out of the prison. She uses flashbacks to what happened to the characters before they arrived at the prison, and any time she can get them out on a van, on a field trip, out in the yard, or any other exterior location, she does.

The pilot of The Walking Dead isn’t any different from a movie visually; it is very expansive. But it was also difficult and expensive to produce, so as the show progressed, the writers created more containment on the ranch and in the prison. Multiple locations are costly and such production values are difficult to replicate on a weekly basis with a tight production schedule.

So early television based on theater evolved into the use of close-ups and today competes directly with the cinematic experience. Non-verbal communication became increasingly more important. In today’s shows, especially on cable and digital platforms, there’s no difference between television dialogue and movie dialogue. Less is more—writers write less obvious dialogue in favor of implied subtext. Description includes visual sequences that reveal much of the story, and the writer also employs more subliminal exposition instead of putting it in the mouths of the characters. The viewer can drop into the story and just see them in action and understand what’s going on. If we don’t immediately grasp what’s going on, we trust (because we are now more savvy television viewers) that we will learn and get all the information we need as the story progresses.

Again, one writing exercise is to compose a first draft where the dialogue is on the nose and gets all the information and facts and the main information of the scene out. After digging in and tracking, the next step is to go back and bury the information and camouflage it, putting in subtext and finding things that are better left unsaid, or better “written” through describing the action and character’s body language. Another helpful exercise is the opposite of that—namely, to first write the scene with no dialogue at all. We can try to convey everything in the scene that we need to convey with the fewest amount of words possible. And then, only add dialogue where it’s absolutely necessary. I read hundreds of scripts, and often the criticism I have is that they’re too “talky.” In general, most people—myself included—overwrite dialogue. And that’s fine when we’re in the drafting process, just putting words on the pages and trying to get people talking. We also overwrite dialogue initially because we’re just trying to understand who these characters are and get a sense of their voices and what they might sound like. But bear in mind that we need to then go back and rewrite it. There was a term I learned when working on Steven Bochco’s show, Doogie Howser, M.D., Bochco used to talk about “raking your dialogue,” like raking leaves. He would say, “Put all the dialogue down that you want, but then rake it, and take out all the unnecessary words. Just keep the essence of what the line needs to be.”

In general, I find that less is more, and if a character can say something with a look and no dialogue at all, that’s the best. If we can have a character say something in one sentence rather than five, the one sentence is probably better. In our effort to write only what’s necessary in dialogue, we need to remember to write only necessary non-verbal actions and expressions. As Amy Sherman-Palladino points out in the quote at the beginning of this chapter, “Why do you have to have four expressions, and then look and think?” So, it’s a fine balance between what’s spoken and unspoken. If we stay true to our characters, this will come across on the page in their verbal and non-verbal communication.

Point of View and Subtext: The Last Man on Earth, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend

When we talk about subtext in a scene, point of view is essential. Point of view basically means, does a character know more than other characters, or less? Who has information in a scene, and who doesn’t? Good scenes are about power dynamics between the characters. And as we all know, information is power. If a character knows more than another character in a scene, we can get rich subtext out of that. And if two characters know more than all the other characters, we get rich subtext out of that, too. There are all kinds of dynamics in terms of who knows what, and when. The suspense and the subtext of such a scene is all about the audience having information that some characters do not have and playing out the tension, or the fun, of that kind of close call.

An example of this kind of subtext in comedy can be found in “She Drives Me Crazy,” in Season 1 of the hilarious The Last Man on Earth on Fox. Phil (Will Forte), who thinks he is the last man on earth after a mysterious apocalypse, has met and married Carol (Kristen Schaal), who is not his dream girl but seems to be the last woman on earth. So in order to have sex again, and based on Carol’s demand that she won’t sleep with him unless they’re married, he thinks, “What the hell, I’ll marry her.” Right after they tie the knot, he discovers there’s another female survivor, a beautiful blonde named Melissa (January Jones). He recognizes he’s made a huge mistake, because if he’d known that Melissa existed, he would have never married Carol. In every scene, Phil tries to find ways to get closer to Melissa. He doesn’t really care what happens to Carol at this point; all he can think about is his obsession with Melissa. Then, another man shows up—an overweight, mustachioed, balding guy named Todd (Mel Rodriguez). What makes Todd such a fun character is that Melissa truly seems to love this less attractive, but genuine, man. The shallow Phil can’t believe that Melissa would actually choose Todd over him. All of the humor in the scenes comes from what is not said and from how Phil squirms and all of his facial expressions. After Todd and Melissa go off together from yet another romp, we see how Phil truly feels, when he goes into the back yard and plunges himself face down in a kiddy pool full of tequila. But when he interacts with Todd it’s all restrained, and the humor comes out of the subtext.

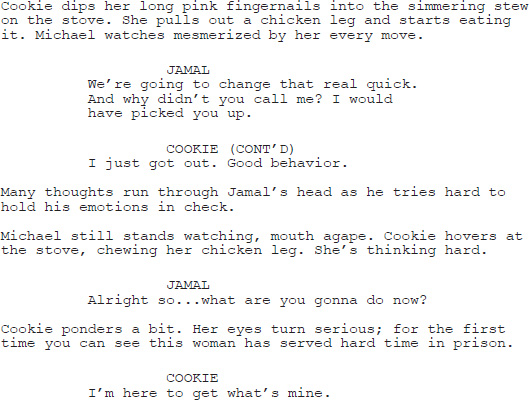

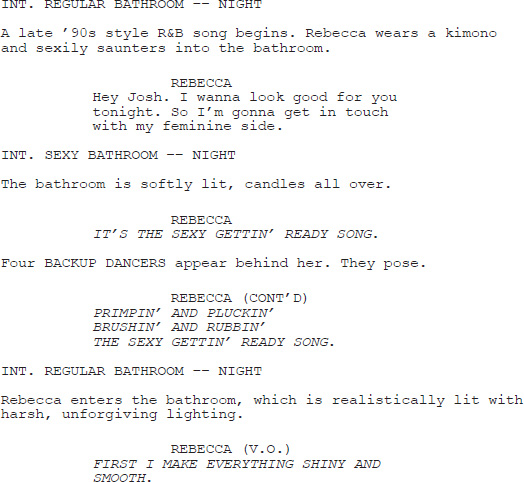

In the pilot of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, Rebecca (Rachel Bloom) spends hours painstakingly getting ready the first time we see the ’90s music video style “The Sexy Getting Ready Song.” Then when she meets her date Greg (Santino Fontana), she shrugs off her appearance, to comedic effect. Bear in mind the effort is actually all for the benefit of Josh (Wilson Rodriguez III), the ex she’s hoping to see at the party with Greg, even though Greg is her date and ticket into the party. The audience is complicit with Rebecca—we have the information that Greg doesn’t, while Rebecca’s song keeps us humming. Here’s an abridged version of the scene.

Writers Aline Brosh McKenna and Rachel Bloom effectively communicate story through song. Their choices of sultry, dated tune—and even rap in the unabridged version—maximize the irony and wit of the smart lyrics. It’s a monologue set to music that happens to rhyme. Sarah Silverman’s new Hulu series I Love You, America also uses lyrics in the place of a monologue, but from an overtly political standpoint. Silverman’s satirical lyrics in the title song are simultaneously an ode to the country and an appraisal of the issues it currently faces, from prejudice to agricultural subsidies. The song’s subtext, which Silverman eventually admits in verse, is her personal ignorance of key issues, which is indicative of the wider population’s, too. Optimistically, she sings that she wants to improve.

Shop Talk: Brooklyn Nine-Nine

Another example of strong dialogue can be found in shows where each character has a highly specific expertise and point of view. Again, when writing a pilot and creating the ensemble, we need to make sure they’re all very different and hopefully diverse—different ages, backgrounds, perspectives. They don’t all have to be righteous and have politically correct ways of dealing with situations. They can be edgy, desperate and make their own mistakes. They can all have unique relationships with the boss and their own unique relationships with each other. So the way they talk to their boss is going to be different from the way they talk when alone. On the Emmy-winning, fast-talking Veep, for instance, the way that Amy (Anna Chlumsky) and Dan (Reid Scott) speak to each other changes significantly when Selina (Julia Louis-Dreyfus) is present, to comedic effect. For her role as Selina, Louis-Dreyfus became the first actress to win an Emmy category six years in a row. Veep’s sweet spot is when political plans go awry and Selina throws a hissy fit—i.e., frequently. It’s heightened shop talk.

On Brooklyn Nine-Nine, Detectives Jake Peralta (Andy Samberg) and Amy Santiago (Melissa Fumero) are masters of cop speak. Their exchanges are sharp and funny. Late in Season 1, Jake and Amy are concluding a year-long bet on who’s the better cop and can make more felony arrests during the 12 months. If Amy wins, Jake’s Mustang is hers; if Jake wins, he gets to take Amy out in the Mustang. They haven’t realized they like each other—yet. With moments to spare, it’s neck and neck.

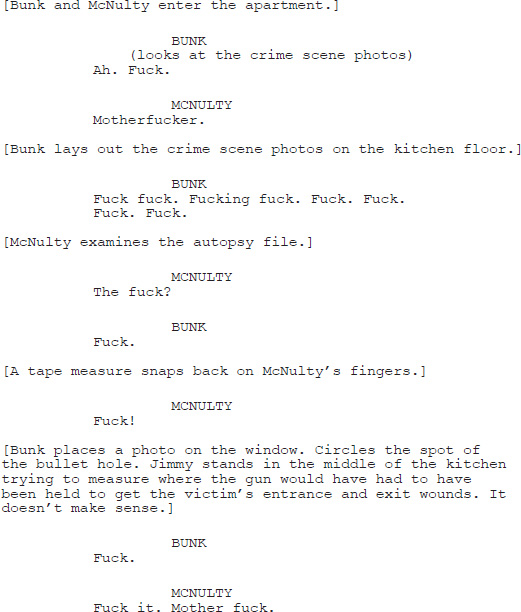

Naturalistic Dialogue: Profanity in The Wire

Some dialogue is written to feel naturalistic; the writers don’t want to draw any attention to it. They want us to feel as if we’re eavesdropping on realistic situations—such as in the infamous scene of “all fucks” from The Wire. As they keep using the word over and over again, it becomes almost like a game between the two detectives. And then they want the only words to be the f-bomb in the scene. So it starts with the writer’s agenda; the audience then starts to realize, “Oh, wow, these are the only words that are being spoken in the scene.” Then the detectives start to play off each other, and it becomes that game. If writing the scene first just on the nose to get the text out, there’s certain information that has to come out in the scene. But then we can go to our toolboxes as writers and ask ourselves, “What would be a fun, interesting, unique way to show the relationship between the two detectives, to make it more than a typical, dry procedural that we’ve seen a million times?” Since The Wire (2002–2008) was an HBO show, the writers had the freedom to use the f-word. And this was fairly early in premium cable. On a cable show, we’re not limited by Standards and Practices, which controls what curse words can be said on a network. So hey, let’s cut our characters loose and let them talk the way they really would. For good measure, here’s the playful scene from Season 1, Episode 4, entitled “Old Cases”:

Backstory: What They Don’t Say

In addition to giving every character in an ensemble a point of view, remember, characters always have history. Novice writers often write scenes as if characters never existed before that scene. But we need to remember that characters have a whole life, a whole backstory that informs the present. They bring and carry that around everywhere they go. In pop psychology, this is called our baggage. Some of this is helpful to us, while some just bogs down and limits us. But if we don’t have an ensemble, let’s say we just have a scene with two characters, bear in mind that history can be 20, 30 years into the past or more—or maybe just from last week.

Characters don’t need to speak in complete sentences. They will have inside jokes and their own shorthand with each other, based on other characters’ histories and their own, and it’s perfectly fine not to explain what those things mean. The audience will understand that part of the relationship is these inside jokes, and the shorthand between characters. That’s going to speak louder about a relationship than having characters say, “Well, you know, we’ve been married for 25 years now, and this is something that has come up a lot in our relationship.” Just have them react to each other in a way that shows they’re annoyed, and have it convey those 20-plus years of marriage. It’s going to be far stronger than having people explain things. Trust that the audience is going to understand what’s going on. If they don’t, that’s OK too. So much of what makes scenes rich and interesting is a sense of mystery.

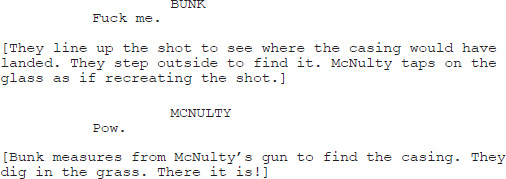

An example of not writing what the characters are thinking is in Season 1, Episode 8 of The Handmaid’s Tale, “Jezebels.” In this scene, the Commander (Joseph Fiennes) has dressed Offred/June (Elisabeth Moss) in a slinky gown and asked her to put make-up on, saying that he has a surprise for her. They’re in the back seat of his car, being driven by his chauffeur Nick (Max Minghella), who is having a forbidden affair with Offred. And unbeknownst to the Commander, Nick and Offred have real feelings for each other. Look at how Kira Snyder, the writer, forces Nick into this uncomfortable situation:

Nick’s response is both respectful and contemptuous. The two words are loaded with subtext, informed by his history with Offred.

Actions—And Triangulation

Aristotle, in his classic work on dramatic theory, Poetics, talks about how characters are defined by their actions. Characters are not defined by what they say. They are defined by what they do.1 If we look at our own lives and relationships, often people will say all the right things—“You know I love you, baby”—and then they’ll do the most inconsiderate, selfish thing, with their actions in direct opposition to the words they tell us. It’s more than body language; we know from life that actions speak louder than words, and it doesn’t necessarily matter what somebody tells us. It’s all about the follow-through.

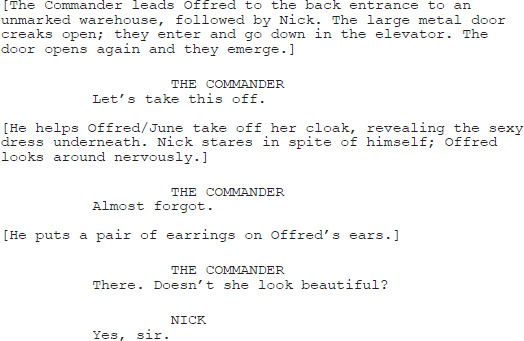

In terms of conflict and power dynamics, any time we have two characters on the same side in a scene with a “weaker” character on the opposing side, we create triangulation. And that’s always interesting, because the audience naturally wants to see who’s going to win. They may root for the underdog, or not, but if the show is well written, they’ll be rooting for one side or the other. The Fargo Season 3 pilot, “The Law of Vacant Places,” gives us a great example of triangulation, as well as character history and point of view. In the following scene, Ewan McGregor plays twin brothers Emmit and Ray Stussy. Emmit has become extremely successful as the “parking lot king of Minnesota”; his brother Ray is by contrast, a struggling parole officer. Ray has fallen in love with one of his parolees, Nikki (Mary Elizabeth Winstead). He’s come to Emmit for money that he feels Emmit owes him, and he’s forced to do it while Sy (Michael Stuhlbarg), Emmit’s right-hand man, literally looks down on Ray.

As we all know, money is power. Emmit’s choice to have Sy present is a subtle action that speaks volumes about Emmit’s relationship to his brother, as well as to Sy himself.

Overlapping Dialogue: Stranger Things

Characters, much like real people, are often bad communicators. Meaning that, we like to think we’re all good listeners and good communicators, but the reality is, most of us don’t listen well to what other people are saying. So another part of our toolboxes as screenwriters is overlapping dialogue—characters can interrupt and talk over each other.

In this scene from “Chapter One: The Vanishing of Will Byers,” the Stranger Things pilot, four 12-year-old boys talk excitedly while playing Dungeons & Dragons. (Note that they are interrupting each other throughout, even though there’s only one actual example of “dual dialogue.”)

Economy With Words

There should never be a line of dialogue in a script that doesn’t have a reason to be there. No line can just sit there because it’s a piece of information that needs to come out. Every line needs to be special and merit its existence on the page. Even when a line serves a function in a plot, it needs to be special in that it’s coming from a character’s unique voice. Any time dialogue starts to feel generic and interchangeable, it starts to feel flat. Specificity is highly important in dialogue. Think of setting as another character. Where characters come from, their ethnicity, education levels, how they speak, do they have an accent, how is their vocabulary? Do they use malapropisms? Do they speak differently in different situations depending on who they’re around? All these things add up and when we’re going through our scripts, even if we don’t know the solutions at the time, circle any line that feels as if it doesn’t have any sense of personality or anything distinctive about it. And think first, does that line need to be there, could I cut it? And second, if we can’t cut it, could it be a non-verbal action line, communicated through body language? If it can’t be cut verbally, what’s a unique way for that character to say that specific line?

E-Communication

Actors will make dialogue uniquely their own. I find that the better the actor, in general, the more comfortable they are with not having a lot of lines of dialogue. The best actors I’ve worked with feel they can convey what they’re feeling with a look or a sense of attitude. There’s the joke that actors go through a script and say, “Bullshit, bullshit, bullshit, my line, bullshit, bullshit, bullshit.” But I think that’s just a stereotype. I think that actors have realized just like audiences have that the way we communicate has become much more sophisticated and technological. Consider how we communicate with texts and emails. If I’m going to call somebody, or have a phone conversation, it has to be important—because texting, email, Instagramming and Facebooking are more efficient. Our efficiency in communication crosses over into how we communicate in our daily lives, because if we have something important we want to discuss with somebody, often their response is, “Well, didn’t you get my text?” A USA Network show from a few years back, The Starter Wife, was about a woman whose Hollywood executive husband breaks up with her in a text. Computers and smart phones have created a sea change in how we communicate; we communicate in fragments, soundbites and pieces of quick information that can be exchanged through little acronyms of text and emojis. It’s also affecting how we speak when we are together. In Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why, at least 30% of all communication between teens is via text—which often leads to misunderstandings and hurt feelings. Electronic communication is efficient and constant, but is it more empathetic? Does it facilitate better understanding and bring us closer together or have the opposite effect: alienation? Texting is exchanging information, not a pure dialogue. There’s no eye contact, no sense of inflection, no facial expression. In rare cases, it can be dangerous, the inferred leading to a subsequent actual conversation—as damage control. Even Facetime and Skype video cannot replace the joy and necessity of in-person communication.

Listening to Our Characters

The best dialogue comes from people who are good listeners. Screenwriters need to be great listeners. We need to eavesdrop on conversations, listen to how people talk, listen to the rhythms. Go out if feeling blocked, stuck or incapable of writing sharp, authentic dialogue. Go to a shopping mall, go to a restaurant and just eavesdrop on people. How do they speak, what’s the subtext in the scene, what’s the body language? That level of specificity adds layer upon layer to a script that starts off flat, maybe with text that’s obvious, then we camouflage and layer it with subtext and nuance. That’s the goal, and that’s what we’re hoping to nail in every script before it goes out.

Bonus Content

Bonus Content

Further analysis on dialogue, including Bones, Orphan Black, The Americans and Scandal, is at www.routledge.com/cw/landau.

Note

Episodes Cited

“Pilot,” Empire, written by Lee Daniels & Danny Strong; Imagine Television/20th Century Fox Television.

“West Covina,” Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, written by Rachel Bloom and Aline Brosh McKenna; Lean Machine/Black Lamb/racheldoesstuff/The CW.“The Bet,” Brooklyn Nine-Nine, written by Laura McCreary; Universal Television/NBC Studios/20th Century Fox Television.

“Jezebels,” The Handmaid’s Tale, written by Kira Snyder; Temple Street Productions/Hulu.

“The Law of Vacant Places,” Fargo (Season 3), written by Noah Hawley; MGM Television/FX Productions.

“Chapter 1: The Vanishing of Will Byers,” Stranger Things, written by the Duffer Brothers; 21 Laps Entertainment/Monkey Massacre/Netflix.