I speak as a proud liberal.

I speak as a strong supporter of President Obama.

I also speak as a liberal Democrat disappointed in his presidency, because he let progressives down so badly.

Indeed, you could sum up this book in one sentence: On too many issues, once he got to the White House, President Obama abandoned his campaign promises and disappointed the people who worked so hard to elect him.

At this point in the twilight of the Obama administration, looking at the differences between what was promised and what was delivered, more and more progressives want to know:

We voted for hope and change, Mr. President, but what did we get?

Sure, we got a better economy than Bush left us with, but we also have stagnant wages, a struggling middle class, rising income inequality, and a diminished social safety net.

Sure, we got “health insurance reform,” but without single-payer and with a monopoly for private insurance companies.

Sure, the Iraq and Afghanistan wars were ended, but now we’re still in Afghanistan and back in Iraq and Syria, fighting ISIS.

Sure, we decimated al Qaeda’s leadership, but now we’ve got killer drones raining death from the sky without due process, and the NSA spying on all our phone calls and emails.

And that’s just the beginning.

Throughout this book, we’ll go over the countless ways Obama fell short of what he could have accomplished. Time and again, he abandoned the progressive beliefs he’d promised to uphold, on issues across the board, from the economy to the environment, from immigration reform to gun control—yes, even on health care.

Ironically, from a progressive point of view, Obama’s best years may be his last two years. It was almost as if the burden of elections had weighed him down. Once the midterm elections of 2014 were behind him and he was freed from the obligation to campaign for himself or anybody else ever again, Obama suddenly got tougher and began to flex his political muscles at last, using the power of the executive order to take bolder action on immigration reform and climate change.

But by then, it was too little, too late on most fronts. For the most part, Obama’s efforts were limited to actions he could take using executive powers alone. On Capitol Hill, Republicans, who now controlled both houses of Congress, were often able to block him and did.

That in itself was a painful reminder of all he might have accomplished, but did not, during his first two years in office, when Democrats were in charge of both House and Senate.

What makes our disappointment in Obama so hard to take is: It wasn’t supposed to be this way. For passion and excitement, American politics had seldom seen a phenomenon like the Obama campaign of 2008.

For a dyed-in-the-wool liberal like me, that campaign was especially exciting. It was something I’d been waiting my whole political life for. I got my start in Democratic politics in San Francisco—by volunteering for Eugene McCarthy for president in 1968. I went on to run local and statewide campaigns. I worked for Governor Jerry Brown for four years. I led a statewide initiative campaign and ran for statewide office in California. I served three years as chair of the California Democratic Party.

And since 1980, I’ve been a liberal commentator and talk show host on radio and television. In Los Angeles, on KABC-TV and KCOP-TV, and KABC Radio and KFI Radio. For six years, I was the liberal cohost of CNN’s Crossfire. I also cohosted The Spin Room with Tucker Carlson on CNN, and Buchanan and Press with Pat Buchanan on MSNBC. Since 2005, I’ve been host of The Bill Press Show, broadcast on radio stations nationwide and simulcast, first on Current TV and now on Free Speech TV. And since 2009, I’ve been a member of the White House Correspondents’ Association and attend daily press briefings at the White House.

I’ll proudly match my progressive credentials against those of anybody in the media. I’ve been promoting and defending liberal ideals on radio and television for thirty years. And I’ve defended Obama, too. My last book, The Obama Hate Machine, outlined the relentless, racist, over-the-top (and often Koch-funded) personal attacks by the right against the president.

So, when it comes to fighting for liberals, I feel like I’m the real deal. And in 2008 I thought President Obama was the real deal: the truly progressive president we’ve been waiting and working for all our lives.

And I wasn’t the only one. Even celebrities—otherwise cool, rational people who live and breathe this kind of hype every day—suddenly caught a public case of “Obamamania.” Those gushing over Barack Obama included:

• Halle Berry: “I’ll do whatever he says to do. I’ll collect paper cups off the ground to make his pathway clear.”

• George Clooney: “He walks into a room and you want to follow him somewhere, anywhere.”

• Congressman Elijah Cummings: “This is not a campaign for president of the United States, this is a movement to change the world.”

• Caroline Kennedy: “I have never had a president who inspired me the way people tell me that my father inspired them.”

• Toni Morrison: “Of one thing I am certain: this opportunity for a national evolution (even revolution) will not come again soon, and I am convinced you are the person to capture it.”

• Oprah Winfrey: “For the first time I’m stepping out of my pew because I’ve been inspired. I’ve been inspired to believe that a new vision is possible for this country.”1

The 2008 campaign was one of the most brilliant and strategically executed political campaigns ever. It ran an aggressive, daily, and flawless message operation. It outfoxed and outmaneuvered the fabled Clinton political machine in an extended and hard-fought primary season. And its goal of electing a smart, young newcomer to Washington—and the promise of electing the nation’s first black president—inspired millions of Americans who’d never before taken any interest in politics to get involved: making phone calls, walking precincts, talking to their friends and family, and turning them out to vote.

Voter turnout, in fact, was the greatest demonstration of Obama’s unique appeal. Over 130 million Americans, or 64 percent of the electorate, cast their ballots on November 6, 2008. Those numbers were swelled by a surge in young and minority voters, the vast majority of whom came out to vote for Obama. He won 66 percent of voters ages eighteen to twenty-nine, 66 percent of Latinos, and 95 percent of African-Americans.2

The most important element in Obama’s success may have been first-time voters. He turned them on like no other presidential candidate has ever done. Out of 131,406,895 ballots counted, 15,112,000 belonged to Americans who were voting for the very first time—and 68.7 percent of them gave Obama their votes, adding up to a million votes more than his ultimate margin over John McCain. It’s no exaggeration to say that the Americans whom Barack Obama inspired to go out and vote for the first time in their lives elected him the forty-fourth president of the United States.3

Nobody felt that excitement more than liberals like me, who saw in Barack Obama the kindred progressive spirit we’d long been yearning for. In a sense, we agreed with John McCain when he acidly called Obama “The One.” There was something “messianic” about the candidate. In our eyes and dreams, Barack Obama—the “skinny kid with the big ears and funny name,” as he described himself—was, indeed, “The One,” the one who’d bury the failed policies of George Bush and Dick Cheney, fix the broken politics of Washington, and move the country in a dramatically new and different direction. He promised no less.4

Even the media got caught up in the giddiness of the moment. People made fun of MSNBC’s Chris Matthews when he told then–NBC Nightly News host Brian Williams he “felt this thrill going up my leg” whenever he heard Obama speak during the 2008 campaign. But what liberal didn’t experience that same feeling? It was thrilling to hear Obama vow, after winning the South Carolina primary, that he would carry across the country his message “that out of many we are one, that while we breathe we will hope, and where we are met with cynicism and doubt and fear and those who tell us that we can’t, we will respond with that timeless creed that sums up the spirit of the American people in three simple words: Yes, we can.”5

We were even more convinced we were part of something new and different when Obama clinched the Democratic nomination in June, after a long and intense primary battle against Hillary Clinton, who’d been the overwhelming favorite until just a few weeks before the Iowa caucuses. That night he told a crowd of supporters in St. Paul, Minnesota: “We will be able to look back and tell our children that this was the moment when we began to provide care for the sick and good jobs to the jobless; this was the moment when the rise of the oceans began to slow and our planet began to heal; this was the moment when we ended a war and secured our nation and restored our image as the last, best hope on earth.”6

Five months later, on election night, November 6, anchoring a nationwide broadcast in front of a live audience in San Francisco, I wept openly when Obama and his family walked out onstage at Chicago’s Grant Park to declare victory: “If there is anyone out there who still doubts that America is a place where all things are possible, who still wonders if the dream of our founders is alive in our time, who still questions the power of our democracy, tonight is your answer.”7

The promise was so great. The hope was so real. But it didn’t take long after Obama made it to the White House for that bubble to burst. And it happened so fast.

Of course, you expect the love affair with any president to cool down by the end of a presidency. He or she (someday!) is bound to let you down, sooner or later. What stunned Obama’s liberal supporters, however, was how soon and how often he disappointed them—and how quickly he chose to compromise with conservative forces, rather than stand up to them. Congressman John Conyers learned that early on.

Conyers did not intend to get in trouble when he agreed to appear as a guest on my radio show in early December 2009. Nor did I intend to get the senior Democrat from Michigan, one of the most liberal members of Congress, and a forty-nine-year veteran of the House, in trouble when I booked him. But that’s what happened.

Near the end of our interview, I asked Conyers whether, as a liberal, he was happy with President Barack Obama’s first year in office. After a long, pregnant pause, Conyers replied: “Now, why did you ask me that?” Another pause. Then: “Frankly, I’m getting tired of saving Obama’s can in the White House.” He went on to accuse Obama and then–chief of staff Rahm Emanuel of “bowing down to nutty right-wing” health-care proposals in a desperate attempt to win passage of the Affordable Care Act, and complained about liberals in the House being forced to hold their nose and vote for a health-care bill that no longer contained a “robust public option.”8

Conyers’s blast at Obama made the front page of The Hill newspaper the following morning. Two days later, he was back on the front page—as the recipient of an angry phone call from the president himself, who told Conyers he was not pleased that the senior African-American congressman was out on the radio “demeaning” him. It wasn’t personal, Conyers assured the president, just an “honest difference of opinion on the issues.”9

Like any good foot soldier, Conyers then walked back his criticism somewhat. But too late. He’d already spoken aloud what many liberals were already feeling even this early in the Obama presidency: disappointment with Obama’s caution in the top job, and frustration at his apparent reluctance to seize the reins of presidential power and run with them.

Even by December 2009, all too many progressives had come to the same grim conclusion as Conyers: Barack Obama the president wasn’t at all what we had come to expect, or been promised, by Barack Obama the candidate.

That doesn’t mean liberals were sorry they voted for Obama. They certainly didn’t regret not voting for John McCain or Mitt Romney. They just felt let down. On so many issues, progressives began wondering: What happened to “Change We Can Believe In”? What happened to “the Fierce Urgency of Now”? Or, as John McCain’s vice-presidential candidate, Sarah Palin, once teased Democrats: “How’s that hopey, changey stuff working out?”10

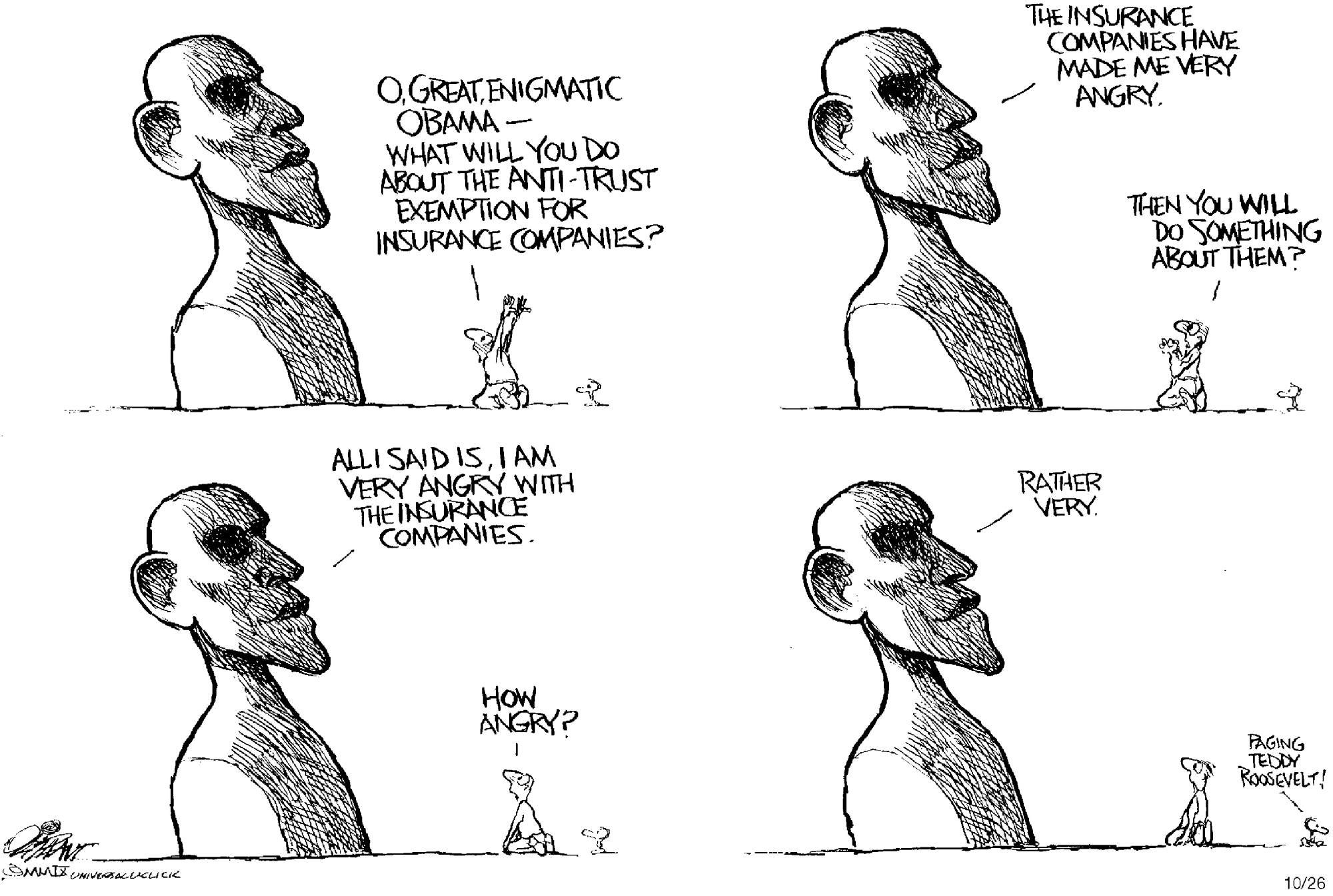

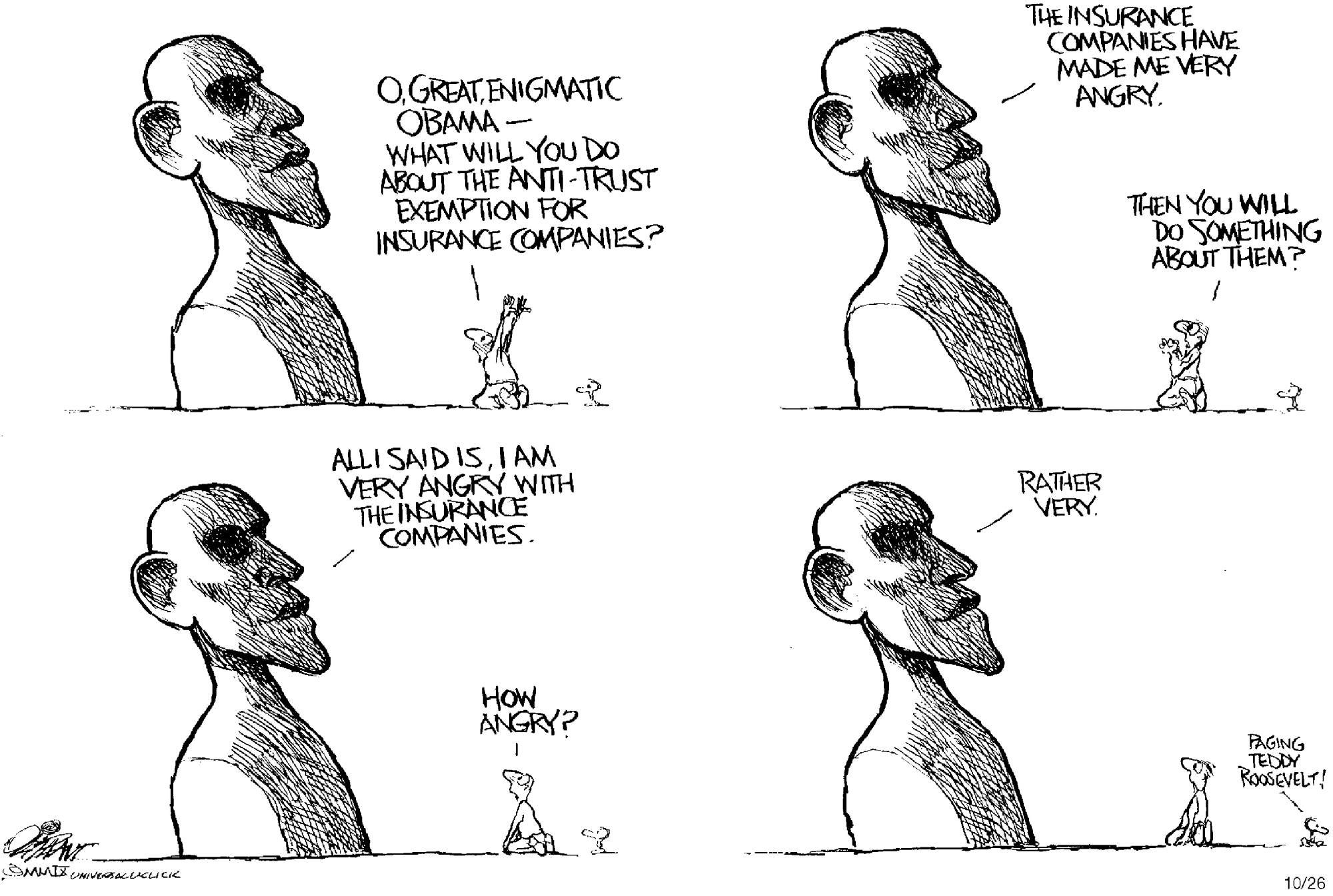

By that time, too, the media had begun to reflect the disillusionment among many Democrats. On February 24, 2009, only thirty-five days after Obama’s inauguration, Pulitzer Prize–winning political cartoonist Pat Oliphant depicted the new president as a cold, distant, aloof, and inscrutable Easter Island statue, who avoided any direct answers to pleas from supporters about what he was going to do about the nation’s many problems, now that he was in office. In a September 2014 interview for The Atlantic, political reporter Les Daly asked Oliphant if he felt “extraordinarily incisive and prescient” in being the first to note a character flaw in Obama that everybody was talking about six years later. “I’ll take that,” the Australian-born cartoonist responded. “I just had this feeling about him, that maybe he thought he shouldn’t be there. We were looking for and imbued him with qualities which he never had and still doesn’t have, inflated expectations.”11

Eight months later, October 26, 2009, Oliphant depicted Obama back on Easter Island, refusing to say what he’d do about tax breaks for big insurance companies. Oliphant closed by having his signature character Punk plead: “Paging Teddy Roosevelt!”12

In his book Revival, which charts Obama’s rough-and-tumble efforts to build support for health-care legislation, author Richard Wolffe notes that by the time Obama signed the Affordable Care Act in March 2010, it looked like Washington had changed him more than he had changed Washington. “He campaigned as an outsider who could battle the nation’s vested interests and the tired old political class,” Wolffe writes. “Yet he seemed to govern as an insider who would cut deals with those same vested interests and who was beholden to the same political class. The sense of authenticity in his candidacy gave way to the conventional tokens of the presidency: a round seal stuck to a stocky podium, precooked remarks on a teleprompter, a motorcade led by two limos with darkened windows.”13

If there’s one word I hear from progressives about President Obama more than any other, it’s “disappointment.” That one word seems to sum up his presidency. And disappointment with Obama only grew with each succeeding year. “I don’t think that anyone at this point would characterize the president as the progressive warrior that the progressive movement is anxious to see,” Rep. Alan Grayson (D-Fla.) told Politico in September 2013.14

At the Toronto Film Festival in September 2014, liberal filmmaker Michael Moore told The Hollywood Reporter that Obama would be remembered for only one reason: “When the history is written of this era, this is how you’ll be remembered: He was the first black president.” Moore added: “Eight years of your life and that’s what people are going to remember. Boy, I got a feeling, knowing you, that—you’d probably wish you were remembered for a few other things, a few other things you could’ve done.”15

Grayson and Moore had company. Asked about his views on Obama five years into his presidency, left-leaning actor and advocate Matt Damon told BET in August 2013, “he broke up with me. There are a lot of things I really question, you know: The legality of the drone strikes, and these NSA revelations . . . you know, Jimmy Carter came out and said we don’t live in a democracy. That’s a little intense when an ex-president says that. So you know, he’s got some explaining to do, particularly for a constitutional law professor.”16

A year later, professor and prominent liberal intellectual Cornel West was even more dismissive. “The thing is, he posed as a progressive and turned out to be counterfeit,” West told Thomas Frank in August 2014. “We ended up with a Wall Street presidency, a drone presidency, a national security presidency. The torturers go free. The Wall Street executives go free . . . he acted as if he was both a progressive and as if he was concerned about the issues of serious injustice and inequality and it turned out that he’s just another neoliberal centrist with a smile and with a nice rhetorical flair.”17

One of the harshest criticisms of Obama from the left came from former Ohio congressman Dennis Kucinich, who ran against him in 2008 for the Democratic nomination. In a 2013 interview with Politico’s Edward-Isaac Dovere, Kucinich accused Obama of poisoning the liberal movement by seeming to support it, while actually betraying it. As long as Obama was widely and wrongly perceived as our most “liberal” president, Kucinich argues, he prevented any real liberal agenda from taking hold.18

In May 2015, Esquire magazine interviewed artist Shepard Fairey, who created the iconic “Hope” poster that became Obama’s political calling card in 2008. When asked if he thought Obama had lived up to his promise in that campaign, Fairey replied, “Not even close. Obama has had a really tough time, but there have been a lot of things that he’s compromised on that I never would have expected. I mean, drones and domestic spying are the last things I would have thought [he’d support.]”19

You could almost feel the air leaking out of a balloon. It reminded me of the euphoria I first experienced among young people in San Francisco in 1967, true believers in the revolutionary, transformative nature of the countercultural movement of the mid-sixties—and the huge letdown we experienced watching it all fall apart with the blowup of the Vietnam War, the violence in Chicago’s Grant Park, the election of Richard Nixon, and the triumph of the establishment.

At that time, nobody described the transition from hope to disappointment better than Hunter Thompson, in his classic book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. “There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning,” Thompson recalled. “And that, I think, was the handle—that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of old and evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave. So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look west, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.”20

Flash forward to the early days of the Obama presidency. As disappointment started to set in, and some progressives dared express it openly, Obama’s team openly ridiculed his critics. In the first year of the administration, former White House press secretary Robert Gibbs bristled at criticism from people he called the “professional left” over Obama’s compromises on health-care legislation: “I hear these people saying he’s like George Bush. Those people ought to be drug tested. . . . They will be satisfied when we have Canadian health care and we’ve eliminated the Pentagon. That’s not reality. They wouldn’t be satisfied if Dennis Kucinich was president.” For all his tantrum, however, Gibbs was kinder than former chief of staff Rahm Emanuel, who lashed out at Obama’s critics on the left as “fucking retarded.”21

Today, as the Obama presidency winds down, progressives find themselves especially disillusioned, frustrated that the change they worked so hard for, believed in, and were promised was never delivered. At least not on the scale they needed or expected. As the economist John Maynard Keynes once said of Woodrow Wilson, another progressive president who promised to change the world, after the Treaty at Versailles in 1919: “The disillusion was so complete that some of those who had trusted most hardly dare speak of it.”22

So, what happened?

Part of the answer may lie in Gibbs’s rant, which, however mean-spirited, did contain a kernel of truth. Let’s be honest: Liberals, as a group, are never satisfied. And, again, I say this as a proud liberal myself. There’s a good reason why politicians often find liberals a thorn in their side: Because sometimes, it’s true, in our heart of hearts we let the great become the enemy of the good, and get too easily dismayed by half-measures. Even if politicians finally get something right, we’ll complain about why it took so long.

At the same time, however, most liberals are also pragmatic realists. We understand the political process. We know we’re never going to get 100 percent of what we want on any issue. And we accept that—but here’s the key—as long as you fight like hell for that 100 percent before you compromise for much, much less. Which is what, too often, on too many issues, President Obama has failed to do.

It’s also possible—in fact, it’s altogether likely—that we fundamentally misread Barack Obama. Maybe we made the same mistake with him we had once made with Bill Clinton. In a kind of national political Rorschach test, American progressives across the board projected onto Obama their own liberal beliefs and dreams. African-Americans were proud of one of their own. Latinos saw the promise of a minority brother on immigration reform. Women respected a man raised by a single mother and unusually sensitive to women’s issues. Young people gravitated to Obama’s laid-back cool, and his openness on issues like his early drug use. And limousine liberals welcomed the black man who was more comfortable on the Upper East Side than in the housing projects.

Obama appeared to be all things to all people. But, as Vermont’s congressman Peter Welch observed, perhaps no human being could meet those outlandish expectations: “The president was the embodiment of the dreams and aspirations of a better country and better future. To some extent the person that he’s not is a person that he ultimately could never be.”23

A closer look at Obama’s past voting record, however, might have warned us that he was really no liberal at all. As senator, for example, Obama enraged liberals by endorsing—right after winning the Democratic nomination—legislation granting immunity to telecommunications companies that cooperated with the Bush administration in wiretapping American citizens without prior approval of the FISA Court, legislation he had vowed to oppose as candidate. He also shocked progressives by applauding a Supreme Court decision that knocked down Washington, D.C.’s ban on handguns.24

Of course, Obama’s right-wing critics, whom I branded—correctly—in an earlier book as the “Obama Hate Machine,” have always painted his politics as on the extreme left. It’s politically convenient for them to do so. But they’re totally wrong, and they know it. The reason Obama is widely perceived to be so liberal is that the Republican Party has moved so far to the extreme right that Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan look lefty by comparison. Obama’s no socialist or communist. Not even close. But he’s no liberal, either. At best, he’s a bona fide centrist, or centrist-left.

Still, the misperception of Obama as “Mr. Liberal” wasn’t entirely our fault, either. In many ways, we were deliberately misled by the candidate himself.

Candidate Obama certainly had a knack for making us believe he was on our side. After all, this was the man who, at an anti–Iraq War rally in Chicago in September 2002, had called George Bush’s war in Iraq “a dumb war” and “a rash war” at a time when Democrats in Washington were tripping over themselves to vote for it. That speech alone may have elected Obama, but it also blinded us to the fact that Obama was not as progressive as we might think on other issues. Even on Iraq, we never would have believed that he’d wind up sending American troops, even as only advisers, back into that snake pit before the end of his presidency.25

To take another example, consider candidate Obama’s much-heralded speech on civil liberties and the war on terror in August 2007: “I will provide our intelligence and law-enforcement agencies with the tools they need to track and take out the terrorists without undermining our Constitution and our freedom,” he said then. “We will again set an example for the world that the law is not subject to the whims of stubborn rulers, and that justice is not arbitrary. . . . This administration acts like violating civil liberties is the way to enhance our security. It is not. There are no short-cuts to protecting America.” Tell that to Edward Snowden, James Risen, Chelsea Manning, and the prisoners still locked up at Guantanamo seven years later, with no hope of trial.26

Yes, progressives are big dreamers, and perhaps we projected too much onto Barack Obama in 2007 and 2008. But in the end, progressives’ disappointment in President Obama stems from something a lot more substantive than that. It’s based on a grim, simple truth: On too many issues, he let us down. He simply failed to lead.

As will be seen in the chapters that follow, time and time again, when bold leadership was needed, he either refused to fight for what he wanted, gave up too early, compromised too soon, or too quickly settled for half a loaf. Too often, when action was needed, he hit the pause button. When decisions were due, he dithered.

To some extent, that is Obama’s personality. That’s why he’s called “No Drama Obama.” He’s a professor of constitutional law, and likes to deliberate. Granted, after eight years of George Bush’s “shoot first, ask questions later” style of governing, it was refreshing to have a president who didn’t rush into matters, especially foreign wars, without knowing the facts. Still, there’s a big difference between deliberate decision-making and no decision-making. Too often, Obama adopted a laissez-faire style of governing that made him look weak. New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd lamented that America had drifted from “mindless certainty” under George W. Bush to “mindful uncertainty” under Barack Obama.27

One big surprise was that Obama, who is so gifted at making speeches, and drew such huge, enthusiastic crowds during his campaign, put those talents to so little use once in the White House. Many times, when Obama was stonewalled by congressional Republicans on items high on his agenda—the public option, gun safety, an increase in the minimum wage, immigration reform—we in the White House press corps expected him to take off around the country and rally public support in order to put pressure on Congress. But it seldom happened. Instead, most of the time, he’d make one strong statement in the Rose Garden or Briefing Room, or give one rousing speech in front of a friendly audience, then move on to other matters and let others worry about the follow-through.

Vermont senator and 2016 presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, among many others, faults Obama for not using the unique opportunities of the presidency to stoke public outrage. For example, he told Meet the Press: “I think he should’ve gone to the people in a more aggressive way” and rallied supporters of an increase in the minimum wage to descend on Washington in protest.28

In her monumental work The Bully Pulpit, documenting the presidencies of Teddy Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, historian Doris Kearns Goodwin sums up the secret of TR’s success: “The essence of Roosevelt’s leadership . . . lay in his enterprising use of the ‘bully pulpit,’ a phrase he himself coined to describe the national platform the presidency provides to shape public sentiment and mobilize action.”29

The bully pulpit’s still there. Obama, however, seldom used it, and his success rate suffered because of that. Despite having such a great orator in the White House, psychology professor Drew Westen wrote in 2010: “I don’t honestly know what this president believes. But I believe if he doesn’t figure it out soon, start enunciating it, and start fighting for it, he’s not only going to give American families hungry for security a series of half-loaves where they could have had full ones, but he’s going to set back the Democratic Party and the progressive movement by decades.”30

There’s one other key factor: President Obama’s stubborn failure to build personal relationships with Democrats in Congress. For the most part, he simply ignored or snubbed them. He seldom reached out, except to ask for a key vote. And he simply refused to do the kind of schmoozing that, while somewhat phony, means so much to ego-driven politicians. Cocktail parties, exclusive dinners in the private quarters, or movie nights with members of Congress, the calling cards of the Clinton presidency, practically disappeared in the Obama White House. It became hard for members of Congress not to conclude that Obama didn’t like them and didn’t enjoy hanging out with them.

“For him, eating his spinach is schmoozing with elected officials,” Senator Claire McCaskill told the New York Times. “This is not something that he loves. He wasn’t that kind of senator.” West Virginia’s Joe Manchin, a key bridge-builder between Senate Democrats and Republicans, described his relationship with the president as “fairly nonexistent.” And Connecticut senator Richard Blumenthal says he can count “on both hands” the number of times he’s been invited to the White House for any event, large or small, since he took office in 2011.31

If Obama doesn’t like hanging out with Congress, he sure doesn’t want to play golf with them, either. A round of golf is President Obama’s favorite form of relaxation, which he engages in as often as possible. But he clearly doesn’t want to waste any time on the course doing what most businessmen or politicians do: chatting up friends and building relationships. He’d rather play golf with White House aides or old friends than members of Congress. As of November 3, 2015, Obama had played 260 rounds of golf as president, according to Mark Knoller, the White House correspondent for CBS Radio. Only on five of them did he invite any member of Congress. Only once did he invite Speaker John Boehner.32

That fifth round was on July 19, 2015, just days after announcement of a successful Iran nuclear deal, when Obama invited three Democratic members of Congress—John Yarmuth of Kentucky, Joe Courtney of Connecticut, and Ed Perlmutter of Colorado—to join him for a round of golf at Andrews Air Force Base, the first time Obama had played with a full congressional foursome. At our White House briefing the next day, Press Secretary Josh Earnest insisted this was just fulfillment of a promise made long ago to play golf with the four, and had nothing to do with the president’s “full-court press” on the Iran agreement.33

Two days later, Yarmuth told me on my radio/TV show that the president never discussed Iran during the four hours on the golf course. But, as he was climbing into his SUV for the return to the White House, Obama told them: “Don’t be surprised if I call on you soon to talk about the Iran nuclear deal.” All three Democrats ended up supporting it.

That still remains the one and only time Obama arranged an outing with congressional members only. Having a drink, watching a movie, playing a round of golf together may be the old kind of politics, but it was politics that Democrats like Lyndon Johnson and Bill Clinton excelled at. And as both would tell you, staying aloof from Congress is not a recipe for legislative victory.

Ironically, while avoiding contact with Democrats, Obama spent an inordinate amount of time meeting with House Republicans, especially in his first term—and none of those meetings produced any positive results. After several one-on-one private meetings with John Boehner, for example, the president and the Speaker announced they’d agreed on a “grand bargain”—a balanced mix of spending cuts and new outlays for the next year’s budget. But no sooner had Boehner returned to the Hill than Majority Leader Eric Cantor and Tea Party Republicans pulled the rug out from under him, rejecting the grand bargain outright.34

Still, Obama continued meeting with Boehner and others, determined to achieve his goal of becoming the “postpartisan” president he’d rhapsodized about during his campaign. He didn’t seem to realize that, with this gang of Republicans, that dream was impossible. They rejected the very notion of compromise. Their goal was to prevent Obama from succeeding at anything. Whatever he was for, no matter how reasonable, they were against—even if they’d supported it before, under George W. Bush. Everybody in America seemed to understand that except Obama himself.

The Republicans’ anti-Obama agenda was made most pointedly by Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell in an interview with the National Journal’s Major Garrett in October 2010. It was all very straightforward, he admitted. The number-one legislative goal of Republicans was “for President Obama to be a one-term president.” Knowing that, many Democrats openly questioned why Obama was wasting so much time meeting with Republican leaders. “He just can’t sit in a room and negotiate with people who refuse to negotiate,” fumed Senator Bernie Sanders.35

Sanders spoke for many progressives. I got nervous, sitting in the White House briefing room, every time I heard Obama brag about how far he was willing to go in compromising with Republicans. He told reporters from AP in August 2012 that if Republicans were willing, “I’m prepared to make a whole range of compromises” that would irritate his party. That same month the New York Times reported: “He particularly believes that Democrats do not receive enough credit for their willingness to accept cuts in Medicare and Social Security.” The essence of the president’s so-called grand bargain, in fact, was that Republicans would agree to tax increases on the very wealthy if Democrats would agree to cuts in benefits for the elderly, including cuts to Social Security brought about by “chained CPI”—a different way of calculating cost-of-living adjustments that would result in lower monthly benefits.36

“Stop this train,” I was tempted to shout out loud, “I want to get off.” We didn’t elect Obama to be the “compromiser-in-chief,” cutting programs like Medicare and Social Security that Democrats had fought so hard for and that millions of Americans depended on.

And yet, as Washington Post columnist E. J. Dionne put it in 2010, Obama seemed addicted to making “preemptive concessions . . . [he] seems to have decided that showing how conciliatory he can be is more important than making clear where he stands . . . he will soon have to decide whether he wants to be a negotiator or a leader.” As it was, Obama’s conciliatory strategy—which Drew Westen called “the politics of the lowest common denominator”—was a failure. It “is always a losing politics,” Westen points out. “It sends a meta-message that you’re weak—nothing more, nothing less. . . . And in fact it is weak.”37

Obama’s indifference toward Congress and the gritty business of politics manifested itself in other ways as well. The last thing he wanted to do was get down and dirty in congressional battles, not even for his own legislation or nominees. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid told the New York Times of an Oval Office meeting on Iraq in late June 2014 with the four congressional leaders: Reid, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell, Speaker John Boehner, and House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi. After Obama had briefed them on Iraq, Reid told the president he had one other important matter to discuss: the fact that Senate Republicans continued to block confirmation of dozens of Obama’s qualified nominees for ambassador.

Reid fully expected the president to join in and put some Oval Office pressure on McConnell. After all, the president had given several speeches urging Republicans to confirm his ambassadorial appointments. Instead, Obama coolly dismissed the whole idea and cut off any further discussion with a curt: “Harry, you and Mitch work it out.”38

It was hardly the first time Democrats in Congress had looked for leadership from the White House and didn’t get it.

The most important lesson I learned on the debate team at Salesianum High School in Wilmington, Delaware—one that served me well for years on Crossfire, Buchanan and Press, The Spin Room, and The Bill Press Show—was how to anticipate and respond to arguments from the other side. Whatever the topic—the death penalty, nuclear disarmament, or homelessness—we spent as much time anticipating opposition arguments as we did preparing our own case.

That means I’m ready for all the howls of protest I know I’ll hear from many of my liberal, Democratic friends once they discover that I’ve dared write a book critical of Barack Obama. Just watch. Their complaints will be some combination of these five:

• At least Obama was better than Mitt Romney or George W. Bush.

• How dare you criticize a fellow Democrat?

• How can you ignore all the good things President Obama has accomplished?

• You’re overlooking racism. Obama has faced unprecedented obstructions only because he’s black.

• Don’t blame him, blame Republicans in Congress for refusing to cooperate with him.

Okay, let’s deal with those criticisms one at a time, starting with the silliest of all.

Yes, of course, Barack Obama’s a far better president than George W. Bush was or Mitt Romney would have been. But—do we really want to set the bar that low? Any number of Democrats—Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, Nancy Pelosi, Joe Biden, John Kerry, Jerry Brown, Chris Dodd, or Dennis Kucinich—would have been better than Bush or Romney.

But we elected Barack Obama, instead. Why? Not just because he’d be better than Bush. But because we believed we could count on him—certainly over Mitt Romney, and even over Hillary Clinton—to fight for and deliver the progressive agenda.

Maybe our expectations were too high, but we voted for Barack Obama because we expected him to be the progressive champion we’d been yearning for, for years. To the extent he fell short, there’s nothing disloyal or disrespectful about expressing our disappointment.

There are some Democrats who believe you should never publicly criticize another Democrat. No personal attacks, but no public disagreements on policy, either. Politics is a blood sport, so party loyalty above all.

Yes, I know that school of Democrats exists. I just don’t belong to it, and wouldn’t want to join. I’ve been a Democrat all my life. But I’ve never been a blind party loyalist. Yes, I usually vote the party label, but I’ve also voted for a few Republicans in my life. And when evaluating presidents and political leaders, I look at the public policies they put forward, not just the D or the R behind their names.

Early in my television career, I blasted President Reagan on everything from Star Wars, to Iran-Contra, to the War on Drugs. But I also supported his actions on immigration and nuclear disarmament.

Later, at CNN, I roasted George W. Bush on countless issues: tax cuts for the rich, stem cells, the unmasking of Valerie Plame, the Iraq War. But I also supported him on immigration reform and his initial invasion of Afghanistan to overturn the Taliban.

It should go without saying that I would apply that same “play it as it lays” philosophy to Democratic presidents. I was one of the first TV commentators to criticize Clinton for his new Pentagon policy of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” I also didn’t hesitate to condemn Clinton for signing the Defense of Marriage Act. But when the Monica Lewinsky scandal broke, as cohost of CNN’s Crossfire, I defended Bill Clinton from day one. Not because his personal behavior was acceptable, but because whatever happened between him and Lewinsky, two consenting adults, was not an impeachable offense.

On television, on radio, in print, and in this book, I have applied that same “speak truth to power” approach to President Obama. Most of the time, over the last seven years, I’ve been in his corner. But when he’s fallen short and failed to deliver—or, worse yet, when I believe he’s gone in the wrong direction—I won’t hesitate to say so.

In my view, the willingness to criticize our own is one thing that distinguishes conservatives from liberals. Generally speaking, conservatives, usually hierarchical and authoritarian in temperament, will always coddle their own. That’s where what’s often known as Reagan’s “eleventh commandment” comes from—“Thou shalt not speak ill of other Republicans.” But liberals should either support or criticize their own, depending on where they stand on any given issue. That’s the liberal tradition I proudly embrace: to seek and speak the truth, even if it’s rough on a fellow Democrat.

I’m the first to admit there’s a lot in Barack Obama’s record that progressives can rejoice about. And I’d be wrong, and this book would be incomplete, if I did not recognize those achievements.

I certainly believe in giving credit where credit is due. So let’s acknowledge the progressive honor roll Obama has racked up. On that list, I would include, in no particular order:

The Supreme Court: Given the openings provided by the resignations of Justices David Souter and John Paul Stevens, President Obama made two outstanding appointments to the Supreme Court: Sonia Sotomayor in 2009 and Elena Kagan in 2010. Together with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, they make a powerful and long-overdue female bloc of votes, easily intellectually outpacing conservative justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito.

Gay rights: While it may have taken far longer than it should for him to come around, Barack Obama’s still the most gay-friendly president America has ever seen. Flat out. Nobody else comes close. That’s partly a reflection of his times. But it’s also a tribute to his growth. In the area of gay rights, Obama will be celebrated for four major accomplishments: ending “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”; overturning the Defense of Marriage Act; naming hundreds of LGBT Americans to key positions in his administration; and helping make same-sex marriage the law of the land.

Criminal justice reform: Legislation to reform federal sentencing guidelines—which are racially biased and result in a disproportionate number of young African-American males in prison for nonviolent crimes—had bounced around Congress since the mid-1990s with no results. That finally began to change under President Obama. He signed the Fair Sentencing Act, which reduced the disparity between the penalties for crack and powder cocaine and eliminated the five-year mandatory minimum sentence for crack possession. He supported legislation in Congress to reduce sentences for those already serving time for nonviolent drug offenses and allow well-behaved prisoners to earn shorter sentences. And, as of October 2015, without waiting for Congress to act, he had commuted sentences of eighty-nine inmates in federal prison for nonviolent crime—a drop in the bucket, but still more commutations than granted by Presidents Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush combined.39

The economy: There are still fundamental weaknesses in the economy, as President Obama is the first to admit and as we lay out in Chapter One. But Obama can still point to success on several fronts. He brought the economy back from the brink of disaster. As of November 2015, the Obama administration could boast of sixty-eight straight months of private sector job growth and more than 13.5 million new jobs created. He rescued the auto industry. Corporate profits are at a record high, and, despite some shakiness in the summer of 2015, the stock market has more than doubled since January 2009. Unfortunately, that rising tide did not lift all boats. While the wealthiest Americans fared very well, the poor got poorer, and middle-class Americans were stuck in neutral: Employee compensation sank to the lowest level in sixty-five years, and wages grew at the slowest rate since the 1960s.40

Health care: We will discuss the disappointing aspects of Obamacare in Chapter Two: the lack of a public option; the fact that it still leaves 30 million Americans without health insurance and requires every American who doesn’t receive health insurance with their job to buy a policy from a private insurance company. But, on the plus side, it must be said that President Obama brought the nation closer to the goal of universal health care than any president before him. As of September 2015, 9.9 million Americans had purchased health insurance under Obamacare and a total of 17.6 million were covered, including those on Medicaid, young people on their parents’ plan, and those who had signed up for their own plan.41

Foreign policy: On the world stage, like every president before him, Barack Obama has been a prisoner of events outside his control. Still, despite the problems we’ll talk about in Chapter Four, he can chalk up some significant foreign policy successes. As promised, he ended the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—only, of course, to engage in another undeclared war in Iraq and Syria. He reversed fifty-five years of failed policy and restored relations with Cuba. And he led world powers in negotiating a historic deal preventing Iran from developing a nuclear weapon.

The excuse for Obama’s shortcomings I hear most often is: Of course, Republicans won’t cooperate with him. It’s racist. It’s all because he’s black. Now, that’s a very convenient excuse. But I don’t buy it. Are there some people who hate Obama only because of the color of his skin? Absolutely. Nobody can deny racism still exists in this country. Yet in 2008, despite the lingering stench of racism, we Americans elected our first African-American president, and we re-elected him in 2012. And Barack Obama stepped in as leader of the free world with all the power, and all the opportunities, every president enjoys, regardless of the color of his skin. Where he failed to exercise that power in support of strong progressive policies, the fault lies with him, not his racist critics.

It’s too simplistic to blame all of Barack Obama’s shortcomings or failures as president on the fact that he’s faced significant opposition because of his race. Republicans in the House did not refuse to pass an immigration reform bill because President Obama’s an African-American. They refused because they believe too many Latinos will become citizens and vote for Democrats. And it’s not because he’s an African-American that President Obama was not tougher on Wall Street, abandoned the public plan option, or expanded the use of killer drones. Those were decisions he made as president. He could just as easily have decided the opposite.

If only those pesky Republicans didn’t control the House of Representatives for the middle four years of his presidency, and both the House and Senate for the final two. That’s the “fantasyland” excuse for Barack Obama. So neat—and so wrong. Of course, Obama faced stubborn opposition from Mitch McConnell and John Boehner from day one. But other Democratic presidents had been forced to deal with a Republican-led Congress. Bill Clinton actually accomplished more under a Republican House than he had in his first two years when Democrats were in charge.

Obama’s problem is that, too often, in dealing with his Republican opposition, he was either too quick to compromise or unwilling to twist arms and knock heads together. At other times, he just didn’t seem willing to fight for what he believed in. He’d watch from the sidelines, refusing to get down and dirty. Or he’d throw in the towel before stepping into the ring. Combine that reluctance with the fact that he also didn’t cultivate many close allies among his fellow Democrats, and you have the perfect formula for a flawed record.

So here we stand now, reaching the end of the Obama administration with a great deal of disappointment. As excited as we progressives were at the beginning of his presidency, we can’t hide our frustration that, on so many issues, Barack Obama refused to exercise the full powers of his office on behalf of the causes we believed in.

So much of the idealism and energy we felt in the beginning has disappeared. Washington is still broken, and people are more disaffected than ever. The income gap between rich and poor is wider. Forty-five million Americans still live in poverty. America’s public infrastructure is crumbling. Despite increasing and incontrovertible evidence of climate change, little action’s been taken. The surveillance state is even bigger, more powerful, and more intrusive. Guantanamo Bay is still open for business. We ended one war in Iraq—only to enter another war in Iraq, three years later, against ISIS.42

And, most disappointing of all, Obama turned out to be a cautious, hesitant, almost timid chief executive, not the dynamic, bold, fearless leader we were all counting on.

As progressive blogger David Dayen wrote in 2010, “Nobody had a bigger challenge coming into office than Barack Obama but nobody had a bigger opportunity. And liberals like myself are generally peeved that the opportunity has been squandered. Yes, squandered: I know I’m supposed to talk about all the accomplishments and victories and how things would have been much worse if, say, McCain-Palin won. That’s a given and it’s not good enough.”43

Again, Obama’s failure to deliver can’t be blamed entirely on Republicans in Congress—nor on George W. Bush, economic hard times, or public malaise. The burden rests squarely on his shoulders. We gave him the job he wanted. We trusted him to take full advantage of the powers of the presidency to move this country in the bold, new direction he promised. The sad fact is, he didn’t.

And I say this regretfully. Not as an Obama critic, but as an Obama fan and supporter. Unfortunately, like so many others, a disappointed Obama fan and supporter.

Today, when many Democrats think of Obama, they feel a bad case of buyer’s remorse. Not buyer’s remorse as in “I’m sorry I ever bought this car.” But buyer’s remorse as in “Man, I sank a lot of money in this car, and it sure hasn’t run as well as I expected.”

In short, Obama squandered the once-in-a-generation groundswell of support he enjoyed and the clear mandate for change he brought with him to the White House. So many of the new people he brought into the system in 2008 have given up on politics, disappointed once more. The transformative new era of leadership Obama promised never happened. His presidency looms as a huge opportunity wasted.

Eight years ago, we chanted: “Yes, we can.” Today, on too many issues, we lament: “Yes, we could have—but we didn’t.”

As the poet John Greenleaf Whittier put it in 1856, “Of all sad words of tongue or pen, the saddest are these: It might have been!”44