It wasn’t all beer and skittles being a Beatles fan. My mate and I were in a record shop in Otorohanga, no doubt buying Beatle records, when a local farmer accosted us in a way that seemed harmless at first, but then turned a bit nasty. I had always had a Beatle haircut. It just grew that way. Suddenly people were saying I looked like Paul McCartney, although I countered by saying McCartney looked a bit like me. In some situations I was able to cash in on the lookalike factor, but on other occasions, like in the Otorohanga record shop, it worked against me.

‘Which one are you then?’ a very serious, short-haired farmer asked. ‘Are you John, Ringo or Dick?’

The mood was tense. Obviously not everyone had jumped on the Beatle bandwagon. I remember seeing a placard in the crowd at Christchurch that said ‘We like Elvis, Cliff, Castro, Mao Tse-tung, but not the Beatles’.

A couple of years later I remember seeing that serious, short-haired farmer, and his hair had been allowed to grow so that it was now covering his sunburnt ears and threatening his collar. The Beatle thing did get in. A message got through. It just took some conservative elements in New Zealand a bit longer.

Even the Beatles noticed our quietness and conservatism. Paul, my lookalike, suggested it might be because of our descent from solid English families. Stiff upper lips down under and all that.

The Beatles left New Zealand, but their influence would be felt for many years. More than that, they changed the world, and that included New Zealand – even if we didn’t know it at the time.

PETER SKERMAN, SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHER, HAMILTON

While the Beatle party seemed from some perspectives to be firing on all fronts, there were obviously pockets of resistance, reaction and indifference. Academics picked up on aspects of Beatlemania that to them were quite sobering. Down in Dunedin, the Beatles’ impact was regarded as being slightly evangelical. Everyone enjoyed the comment of the security guard who, when warned of the impending chaos about to descend on the city, made the immortal remark: ‘Don’t worry, we’ve had Vera Lynn through here twice’, but there were undertones of panic in the actions of Beatles fans. While Vera Lynn had raised hopes during World War II, in a very controlled, ‘orders is orders’ sort of way, the explosion that greeted the Beatles seemed to reflect a sense of relief among youngsters. And deflection.

The Beatles in party mood, as seen on the cover of an album of New Zealand and Australian interviews.

‘You’re entitled to your opinion, but did you have to express it on my Beatle sweater?’

With the nuclear threat hovering, so the men of letters hypothesised, young people anticipated the end of the world. See if Vera Lynn can sing you out of that one – global destruction! But as long as the Beatles, as evangelists, could take young minds off that apparent inevitability, the world might be OK. Cause and effect.

Young New Zealanders had been freaked out by the film On the Beach, the adaptation of Neville Shute’s novel that depicted the world ending with a whimper in Australia (which meant New Zealand too), as mankind choked on radiation clouds. Back then, kids didn’t articulate their chaos the way they do now. They were expected to shut up and pay attention. Boys were the progenitors of the ‘strong, silent type’, and young women in interpersonal situations often resorted to sulking and ‘no-talkies’ as tactical ploys.

So Beatlemania, to a clutch of Dunedin academics, was little more than an emotional release. Far from being a celebration, it was a knee-jerk reaction. To other New Zealanders the Beatles were little more than, variously, loud, spotty, disruptive and disrespectful. In pockets of back country New Zealand, they were seen to be fair game, like some kind of mutant marsupials who threatened New Zealand manhood (and womanhood if you let them anywhere near the sheilas).

I remember going to a party with a couple of mates in Awakino, which was pretty much near the end of the line. The back of beyond in some ways. I was still at school at the time – 1964, the year of the Beatles’ tour. It was the first gathering I had attended where alcohol was the guest of honour. The party was populated by shearers, stock agents, farmers and the odd fisherman/duck shooter. This was rootin’ tootin’ territory. Please Please Me, the album, was booming out of the radiogram as the boys and men gathered in one corner to drink as much beer as they could, in the shortest space of time, and the girls and women – all six of them – clustered in the alcove near a bay window. The issue of the Beatles came up as a talking-point, in between the long silences and rugby monologues, although the jolly sounds of Please Please Me didn’t cause the deteriorating mood of the party. In fact the music didn’t impact at all. To most of the party-goers the radiogram was just playing ‘something off the hit parade’. It was more the length of Kevin’s hair, one of my mates, that caused the meltdown in relationships. Drunken shearers, or sober ones for that matter, had been known to shear the hair of any male who wasn’t short-back-and-sides. The mood became tense as shearers’ bloodshot eyes fell on my hirsute mate. Not that his hair was that long.

Another alienating determinant was the fact that Kevin had struck up a conversation with one of the young women in the alcove. He had crossed the line. And the young woman was apparently a shearer’s girlfriend. The flat DB was making inroads. Normally Kevin was as shy as a backwater trout.

Kevin told the young woman that he had tickets for the Beatles’ concert in Auckland (he didn’t), but that was enough to render her animated and friendly. The woman knew just about as much as he did about the Beatles, which was considerable. That was George Harrison singing ‘Do you want to know a secret?’, Kevin slurred as the DB did funny things to his knees. Paul’s mother was dead, and so was John’s, she replied perkily, as the shearers leered. Lennon-McCartney didn’t write ‘Twist and shout’, Kevin announced, oblivious to the mores of backcountry beer parties. Ringo’s only 5’8”, she trilled, while sipping Montana Pearl, her forehead glistening.

A duck shooter created an unwitting diversion by vomiting in the fireplace. By the time the throng returned its collective leer to Kevin and the young woman, they had disappeared.

‘I’m not too sure what happened next,’ Kevin recalled years later. ‘We ended up mucking about behind the macrocarpas where the frost had long since settled. After all, this was Taranaki in early June. Below us the lights – or light – of Awakino swam, treaded water and then sank altogether. I remember hearing the sounds of “Twist and shout” and the muffled thumps of someone beating the crap out of someone else. That was also when I realised that some bastard had shaved my hair off. I guess that’s what revived me, the fact that my head had become totally open to the elements.’

We now realised, at the age of 17, that pockets of New Zealand harboured reactionary anti-Beatle types, who would eventually be tagged ‘rednecks’. And there were more articulate and intelligent Beatle watchers who remained aloof, preferring to carve their identity through an affinity with other rock life forms. There was also the problem of the Beatles not swearing fealty to that sacred tenet of rock music – anti-establishmentism.

I was always a bit indifferent to the Beatles, and although I appreciated the excitement they brought after a very dull decade in New Zealand (the 1950s), I had began a process of rejecting the dominant British cultural influences in New Zealand at that time. I had too much of this during my growing up years in Hawera in the 1950s (‘Boy’s Own Paper’, etc) and from the first time I went to the movies at the Regent or the Opera House, I refused to stand for ‘God Save the Queen’. Mind you, I still stayed up late to hear ‘The Goons’ and serials like ‘The Day of the Triffids’ on the radio.

I think the kiss of death for the Beatles, for me, was when adults started to like them. My mother thought Beatles wallpaper was not too objectionable! Then there was the time I found myself sitting on a float in a town parade, wearing a plastic Beatle wig, no doubt looking like a right dork.

I was gradually drawn to the more daring (and dangerous?) groups like the Stones and the Kinks. I remember seeing the Pretty Things in concert at New Plymouth, when the drummer Viv Prince ran around the stage in

a drunken state, with a blazing newspaper in his hand. Shortly after this concert I recall

Truth newspaper mounting a campaign against them, which led to them leaving New Zealand prematurely.

My brother, who was living in the USA, sent me an EP of Leadbelly around this time, and this introduced me to a world of music – Black American roots/blues – I hadn’t really known about.

I went to all the Beatles movies but I don’t think I bought any of their LPs after Revolver. I started growing my hair and moved to a job in Wellington after suffering a year or more of small-town Taranaki life. Many years later I found myself in the USA.

I had been there for just a week, beginning a PhD, when John Lennon was shot.

GEOFF LEALAND, UNIVERSITY LECTURER/WRITER, HAMILTON

Rock ’n’ roll per se was not every Kiwi’s icon, and the Beatles were very much a rock band at the outset. Coincidentally, folk music had entered the mainstream on the wings of acts like Peter, Paul and Mary. Many New Zealanders had already been ‘converted’ not only to the melodic, literate folk and acoustic music, but were now coloured by the anti-commercial and anti-hype politics associated with ‘pure’ folk music.

At about the same time the Beatles were making it big, my musical focus was more on folk and acoustic music. The Beatles were very much a rock band in their early years and it wasn’t until they began to develop an acoustic edge, most notably on Rubber Soul, that they took my fancy. They were widening their scope. I used to enjoy Rubber Soul tracks like ‘Norwegian wood’ and ‘Girl’, which John had written using acoustic guitar.

Another Lennon acoustic track, ‘Julia’, off The Beatles (the White Album), was a favourite of mine, although I found the chord changes difficult at the time – and still do. And I’ve always admired Paul McCartney’s all-round musical ability.

Along the way I’ve had a few Beatle-relevant, often accidential experiences: recording at Abbey Road studios, where the Beatles recorded; seeing McCartney and Wings in Amsterdam on their first European tour;

having the master recording of my first album cut at the Beatles’ own Apple studios; visiting George Harrison’s office in London. While in London I also worked with an Indian musician called Keshav Sathe, who knew George Harrison because he had worked on George’s

Wonderwall album.

CHRIS THOMPSON, MUSICIAN, HAMILTON

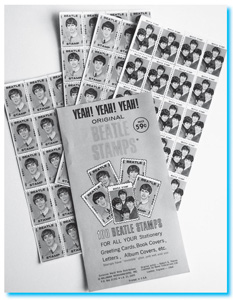

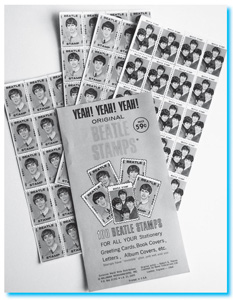

Beatles merchandise for absolutely everything.

Meanwhile back in New Zealand, despite the actions and reactions of some academics, rednecks and others, there was a noisy majority who genuinely did not want to spoil the Beatles’ party.

I already knew my way around a guitar. In a sense that was part of my Maori heritage. What I treasured most about that early Beatle music was the happiness the songs engendered. And yet the chord changes were quite complex. I was living in Matamata at the time, boarding with my sister and brother-in-law, and I had this dinky little record-player that played 45s, but nothing much else. That’s all I needed. As the singles – the 45s – hit the record stores, I’d secrete myself in my room and work out the chords and riffs and words during the week. Come the weekend, I’d go back to my old home town, usually by train, and as I hit the platform at the station I’d ask the locals, ‘Where’re the parties?’

The parties had always been rollicking affairs, but with the arrival of Beatle music they seemed to become cranked up in terms of excitement and spirit. The good times were really rolling.

NEHE PAKI, HAMILTON

And it wasn’t just the new music that added to the excitement. The whole ‘Beatles package’, which now included hair, clothes and attitude, impinged on youthful social gatherings.

For me as a teenager, the Beatles meant an association with ‘cool’. Music I could sing with, a look to dress to, a conversation topic that bonded. We could now talk Beatles talk, like they were doing on the New Zealand hit parade.

Living in a small community of 5000 in the sixties meant going to the

hotel on a Friday and Saturday night was compulsory. The local band would sing the Beatles’ songs and then we’d be off to a party, half-dozen in hand. The guitars would call out and all the known Beatles’ songs would be sung. Then home in the wee hours, to repeat the same thing next week. You could also stand next to the record-player and sing ‘Twist and shout’ as loud as you liked and you felt good. The Beatles were fun. They sang songs of hope and the sheer joy generated at several local Beatle parties became the talk of the town.

I even went to Queen Street in Auckland to purchase a suit and green suede boots that looked the part. I used to hate it if any marks got on the suede, and I remember my mother steaming them over a pot of boiling water to bring the suede to life again. They were very precious to me.

When I wore my green suede boots with their sharp pointed aspect, I couldn’t help making the comparison between them and the solid, roundtoed boots that the farmers wore. It seemed like a long way from stock boots to winklepickers. Times were changing.

I went and saw the movie A Hard Day’s Night with mates, not having a clue what was going on, but seeing the Beatles on screen for the first time.

Another positive aspect of Beatle music was the way the tunes just got catchier and catchier and the beat got more and more persuasive. Despite the winklepickers and Beatle boots, your feet just wanted to dance. In earlier times young people had been wary of the dance floor – even at dances. But now it became natural and acceptable, particularly for guys, to get up and dance.

TONY O’CONNOR, WELLINGTON

And play and sing. The proliferation of bands – invariably four-man (or woman), the gender configuration didn’t seem to matter – was as direct a homage to the Beatles as you could get. Professional bands, semi-professional, unprofessional. Good amateur bands, not-bad bands, bad bands. Tone-deaf dreamers, hamfisted, would-be bird pullers. Some just wanted to be like the Beatles, while others had been genuinely inspired by Beatle music.

Wig and winklepickers: Beatle accessories for the discerning male fan.

Beatles pantyhose was popular among the girls.

I didn’t know what I was going to do with my life. I was reasonably academic and it looked like I’d been earmarked for university. The Beatle thing got in the way of a career decision being made. They were so deflecting. Of course I immediately wanted to be in a band and be like the Beatles. A group of us used to wag school on a Friday afternoon and play the albums, Please Please Me and With the Beatles. We didn’t have guitars in those days but we had tennis rackets. It sounds ridiculous now, but back then it was perfectly normal to stand up and sing along to ‘Twist and shout’, pretending that tennis rackets were guitars. Our sporting activities suffered – including tennis. Appropriately there were four of us, two of whom looked a bit like the Beatles if you saw them in the half-light. Unfortunately they were the ones who couldn’t sing.

We were so inspired by the Beatles we eventually formed our own band of sorts, and started writing a few songs. We weren’t really a band. We tried hard to round up a few interested parties. From time to time we were a quartet, when a mate who played guitar and his girlfriend came down for the weekend from Auckland, but most of the time there was just my mate, who also played the guitar, and me. I wrote a few lyrics and played percussion, utilising a variety of surfaces and objects. Usually I would whack away on something reasonably resonant like a beer crate or the back of a two-string guitar. On many occasions we would retreat to my mate’s parents’ bach at Mokau on the west coast of the North Island. The bach became our Abbey Road. At times we felt like John and Paul, as we wrote songs eyeball to eyeball. My mate, who did a lot of the vocals, actually sounded a bit like McCartney, particularly after a couple of bottles of DB lager.

To compensate for the fact that we were basically a duo most of the time, we got hold of two tape-recorders and played along with one of them, while the other recorded the sound of what seemed like four musicians. We had come up with the idea after realising that the Beatles, from about the time of

With the Beatles, were using over-dubs and doubletracking. By using this crude technique, we overcame the problem of other would-be band members preferring to play rugby rather than join in our jam sessions.

I played a bit of harmonica on occasions and prided myself on the fact that I could belt out a very basic melody line, albeit double-tracked, as Lennon did on ‘Twist and shout’ and ‘Money’. Meanwhile my mate had stumbled upon the idea of playing the bass string on his acoustic guitar as a poor man’s bass guitar. By playing it very close to the microphone it sometimes sounded like the real thing.

I think the first thing we ever did was something called ‘Green bread’, a joint composition based on the fact that we’d both worked in a local bakery in the university holidays. Another early one was ‘The day that Brian got violent’, which chronicled the demise of an unassuming bank clerk from Papakura.

Once while we were playing back a couple of tracks at the Mokau bach, a tenant at a neighbouring property asked us to turn the gramophone down. If he thought our basic noise was something being played on the gramophone, then perhaps, we figured, we should take things a bit more seriously. We immediately started discussing issues like band names for ourselves.

The Beatles based their name in part on Buddy Holly’s band, the Crickets. So we called ourselves the Rugbees, probably because we had been members of the First Fifteen as well. ‘Crickets’ contained elements of team games and insects, and eventually we realised that ‘Rugbees’ did too. Insects became popular as band names for a time: the Mosquitoes, the Praying Mantises (a Christian band apparently), the Cicadas, the Black Widow Spiders (an Aussie girl group). We were going to call ourselves the Cockroaches, which in a later life might have won us notoriety, given the double – or triple – meaning of the word, but back then when the Beatles just wanted to hold hands, ‘Cockroaches’ came across as far too threatening.

We got really serious after the Beatles toured New Zealand. Our next songs were blatant adaptations of Beatle stuff: ‘She loves me’, ‘He loves her’, ‘I want to hold you, girl’. Later, as the flame of fame failed to flicker we just kept going for the fun of it. Eventually we did a series of Beatle parody songs: ‘I want to hold your handle’, ‘Do you want to know a secretary?’, ‘Across the university’, ‘I am the wallboard’. We had a lot of fun.

RUSSELL YOUNG, ACCOUNTANT, TE KUITI

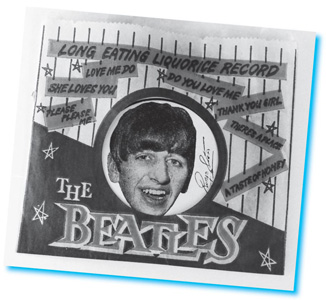

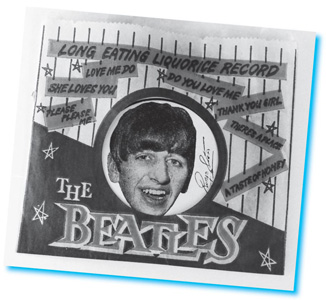

Eat the Beatles. A rare long-eating liquorice 45.