Sometimes New Zealand female Beatle fans had a more complex time of it. Most Kiwi males fell in behind the Beatles because of the music and adolescent hero worship. Had the Beatles been the Beatlettes, four young and attractive British birds, who knows what the socio-sexual dynamics might have been for New Zealand males.

The added ingredient in the mix for female fans was that the Beatles were male. It wasn’t always just the music that fuelled the attraction. In hindsight it was naive for commentators to expect the female contingent of any given Beatle-related gathering to sit on their hands and keep their lips zipped. By the same token, the sheer explosion of emotion displayed by young Kiwi female fans was enough to send psychologists scrambling for their research scales and data measurement devices.

Beatlemania as such became closely associated with female hysteria from the outset of the ’64 tour, with typical symptoms including screaming, sobbing, stumbling and involuntary behaviour. In fact it was concluded by some psychologists that Beatlemania, as they defined it, was a temporary reaction displayed by mainly young adolescent females to group pressures that met their unique emotional needs. It was that simple – and measurable, apparently.

Out in layman’s land such conclusions seemed a little sterile, although it was comforting to learn that if one came down with Beatlemania, there was nothing much to worry about. There was little evidence to suggest that half the nation’s young females had gone mad. They were not hysterical in a clinical sense. No one died as a result of Beatlemania either. Furthermore, it was comforting to learn, in the Kiwi egalitarianism of the times, that Beatlemania straddled the social divide, such as it was back then.

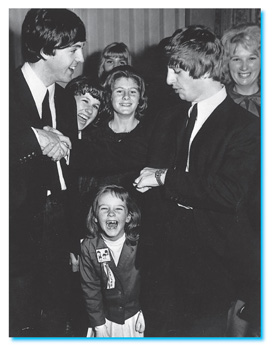

Despite such academic reassurances, the phenomenon of female Beatlemania became an eye- and ear-catching departure from the norm. Out in the field the phenomenon was often quite remarkable. Young females became transported by the Beatles.

I remember sitting next to a young female Beatle fan at one of the Auckland concerts. Before the appearance of the Beatles, while the Phantoms, Johnny Devlin and the other support acts went through their time-honoured rock manoeuvres, the young woman and I exchanged pleasantries, shared aspects of our passion for Beatle music, compared notes on favourite Beatle songs, attempted to out-score one another on Beatle facts – who sang lead on ‘Long tall Sally’, who wrote ‘Don’t bother me’? (It was George, which often caught out the unwary.) When the Beatles walked on to the Town Hall stage, the young female Beatle fan suddenly became someone else. Limbs flailed, while hysterical screaming, tears and strange, guttural sounds suddenly emerged.

The transformation was total. While my male companion and I settled down to attempt to listen to the music, the young female fan continued to perform like a whirling dervish. To an outsider, it may have taken on aspects of an emotional breakdown. It was no wonder psychologists took a particular interest in the phenomenon. Classic symptoms of hysteria were in the air. It wasn’t always mob hysteria either. The girl next to me was one of the first to explode. She wasn’t following the pack. It was an independent explosion of emotion. Perhaps she was a leader of the pack. All mob hysteria has to start somewhere or with someone.

To many New Zealand Beatle fans, females in particular, there was something perfectly symmetrical about the Beatles. Perfect, in fact. Four was a good number to have in a band. It heightened and multiplied the effect. It was a bit like four Elvises, and besides there was safety in numbers. Elvis on his own had been picked off, first by the US Army and then by his parasitic manager Colonel Tom Parker, who wasn’t even a real colonel. Who’d want to call themselves Colonel anyway? Wasn’t the war over? It was Parker who dispatched Elvis to Hollywood to make those formulaic movies and soundtrack albums – Blue Hawaii, Green Hawaii...

You couldn’t imagine the Beatles being manipulated in quite the same way. Safety in numbers again, and a group confidence that helped fire their sex appeal for the ‘screamagers’, as some New Zealand newspapers had it.

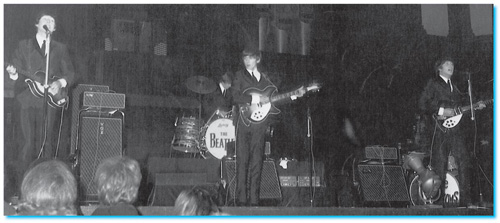

The perfect symmetry was seen when the Beatles took the stage for their New Zealand concerts – two from each side. It might have seemed a minor detail, but such an entrance only heightened the impact. You couldn’t imagine the Everly Brothers or Jan and Dean entering the hall in such a fashion. That would have looked daft. Those two-man configurations were considered a bit incestuous anyway. The average three-piece seemed to live out the adage that three was a crowd. Five and over became shambolic and dysfunctional, like the Beach Boys. The four Beatles seemed the ideal.

John, Paul and George were all exactly 5’11” in height. The casting director of The Monkees TV show would have killed for that sort of uniformity. They all had brown hair and lots of it – even Ringo who, as the sit-down drummer, could afford to be 5’8”. Ringo would never have been the same had he been 5’11” too – the notion of a tall Ringo was laughable.

You could understand why they dropped Pete Best. His hair was stuck in the ’50s rock groove, and a significant part of the Beatle thing was undeniably about hair. Best’s music and personality were very ’50s too. He harked back to James Dean – and Elvis – and the early rock scowl.

Some New Zealand female Elvis fans suggest now that had Pete Best been stationed, scowling, behind the Beatles’ drums, they might not have felt so alienated by the sea change in rock sexuality instigated by the Beatles. Some suggest that John and Paul felt threatened by Best. He might pull more birds. Others claim that the perfect physical and psychological symmetry of the Beatles would have been challenged, in a negative way, by a Pete Best figure. It was now all about wit, forward-combed, non-tensile hair and being part of a team.

There were technical considerations as well. When you hear Best’s playing on some of those very early Beatle recordings you realise that his machine-gun drumming, like a bar-room brawl, was totally inappropriate as an underpinning for the new music the Beatles were peddling. Such obtrusive percussion would have detracted from the excellence of the Lennon-McCartney songs that propelled the Beatles on to the world stage.

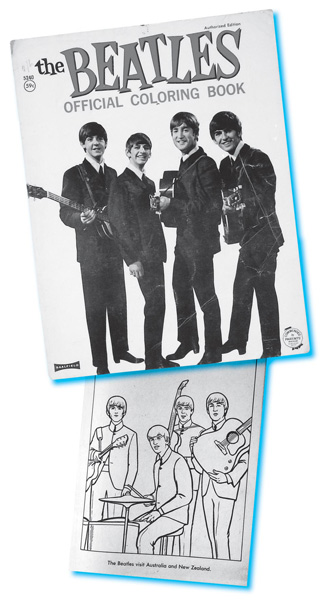

When they toured New Zealand they all performed in matching gear. They deliberately looked like a team. This was in the days before the shallow individualism of rock crept in: the cloying introspection of the rock representatives of the ‘me’ generation. Young people in 1964 identified with the Beatles’ uniformity – and uniforms. After all, they had emerged (or gone AWOL in some instances) from an education system that championed the school uniform.

The uniformity of the Beatles was augmented by Paul McCartney’s left-handedness. When he and George Harrison came together to sing back-up harmonies, it made perfect sense to have George’s guitar pointing one way and Paul’s bass, the left-handed one, pointing the other. When Paul and George joined forces at the first Wellington concert to harmonise the ‘come ons’ in ‘Please please me’, it was a ‘come on’. The girls went into a frenzy. Were those juxtaposed guitars representing something we weren’t supposed to think or talk about? It obviously wasn’t just an issue of uniformity or symmetry.

Musicologists, psychologists and the mere man and woman in the street had a field day with the ‘ooos’ of early Beatle songs. Many would have you believe that the harmonised, whooping ‘ooos’ by Paul and George (and occasionally John, who was married) were some sort of orgasmic vocalisation. ‘I saw her standing there’, ‘She loves you’ and most significantly ‘Twist and shout’ featured the ‘ooos’ as integral parts of the song. At the Beatle concerts in New Zealand, most of which featured these three songs, the ‘ooos’ activated some of the more ear-shattering screams from female concert-goers, so much so that it soon became a talking-point. Were the girls responding to the sound of a male orgasm? Or female? Why did they go nuts at the sound? The common consensus was that until the Beatles came along no one had produced such a mating call – if that’s what it was. The closest anyone came to replicating the phenomenon in rock music was Little Richard with his yelps and squeals, and Elvis with his basic grunts.

The appeal of the Beatles for female Beatle fans was undeniable. When they screamed and vented at concerts it was like a pressure gauge going through the roof.

As well as these public displays of affection, New Zealand girls took the Beatles to heart. If it wasn’t the brazen craving of the older girls, it was the idealised, in-house romanticism of the younger ones, multiplied by four.

Such romantic love would never die. No matter what the four Beatles did, they would remain truly faithful. For other older female fans the emotional attachment was less binding.

For other young New Zealand women, the notion of getting to see the Beatles was just a pipe-dream, although the change in youth culture was tangible.

The youngest female fans, because of their tender years, not only missed out on attending the concerts, but often felt marginalised by the Beatle emotion of the older girls.

I was a 12-year-old not-quite-teenager when the Beatles toured. At first I was a bit overwhelmed, but I soon realised that the Beatles phenomenon was very significant. By reading Diane magazines we were able to keep tabs on their development. My friends and I went through a ‘tennis racket’ stage, when we jumped around to the music, pretending to play guitars. Apparently such an aberration was quite common. You wondered if sales of tennis rackets soared during the Beatle invasion.

I remember getting into trouble because we left a tennis racket or two out in the sun and they became warped. My mother, generally a good-hearted soul, blamed the Beatles before blaming me. I remember Mum humming along to the tune of ‘Please please me’ at the kitchen sink, so obviously the power of the songs was having an effect on traditional ears.

Most of my girlfriends – ‘younger’ Beatle fans – loved Ringo, because he was non-threatening and supposedly cuddly, but I always loved Paul. It wasn’t just because he was goodlooking. His arched eyebrows made him look musical. At least that’s the way I interpreted it.

We identified so closely with the Beatles that my friends and I wanted to form our own band – a girl group. We all started combing our hair forward on cue. Hair definitely became an issue. My older sister used to date guys whose hair was invariably slicked back. I went for guys whose hair flicked forward – like the Beatles. It was a defining aspect of the times, which way your hair went.

Well she was not even seventeen. Christine Targett, as a young bridesmaid, in the tumultuous months following the Beatles’ tour.

In a small town you might have been able to buy the records, but you couldn’t always get items like plastic Beatle wigs. It was hard to know where to go to make such purchases. We tried Woolworths, the music shop and the toy shop. We even tried one of the local barbers. The barber, a grumpy guy at the best of times, positively scowled and sent us packing. In retrospect, I guess he felt threatened in a commercial sense.

Then I learnt my brother was going to the Beatles concert in Auckland. Very few locals had the opportunity. I felt privileged to be able to say that my brother was going to see the Beatles. I was deemed to be too young to go, and although I was initially disappointed, I have to say that the screaming and fainting of many older girls not only surprised me, it scared me a bit too. I guess I didn’t understand that side of it because I was only 12.

CHRISTINE TARGETT, CENTRAL COAST, AUSTRALIA

For some younger girls, the Beatles became very much an abstraction. They loved the music but issues of romantic love did not become an overriding factor. Groups of young girls, some with longer, Beatlesque hair anyway, used to gather in sitting rooms while their mothers were at meetings of the Women’s Division of Federated Farmers and their dads at the RSA, to jump around pretending to be the Beatles. It didn’t matter to them that the Beatles weren’t girls. These young females were happy in their hall-mirrored fantasy to be boys – for as long as it took a WDFF meeting to conclude.

Such antics had nothing to do with latent lesbianism. It was simply a matter of latching on to the faddishness of the Beatles and celebrating the joyous music. At a time when some New Zealand parents reckoned the Beatles were the latest fad to come along after the hula hoop and the twist craze, the Beatles were not expected to last. However some mothers – and fathers – were becoming aware of a certain Beatle longevity and the fact that if they were a fad, they were a good one.

Such parents considered the Beatles to be ‘harmless enough’. It was nice that they were British. Not like Elvis Presley. That chap was in it for the sex, they reckoned. He tended to scowl like a spoilt brat and was a bit too suggestive with his body movements. They had worried about Elvis’s effect on their older daughters, particularly when the latter starting going out with scowling, mongrel types from questionable homes. There weren’t a lot of bad homes back then, but Elvis and his sort seemed to encourage a bit of movement from the wrong side of the tracks.

The Beatles seemed to be enjoying themselves too, many parents noted. They laughed a lot and cracked jokes, where Elvis and his type used to grunt. The Beatles were more wholesome in that respect, reassuring parents who worried about their daughters’ affiliations. Johnny Devlin, New Zealand’s Elvis, had been a bit of a grunting scowler too. Girls used to tear Johnny’s shirt off, although it was later revealed that one of his entourage unstitched the sleeves to make it easier. What sort of nonsense was that!

These Beatles wore suits – and ties. The early Beatle suits initially looked as if some girls had already torn the collars off, but then it was revealed that that was the way they had been tailored. Collarless. A new look. Perhaps the Beatles’ tailor had anticipated trouble with girls tearing at the collars and had decided to outwit them by having no collar to begin with.

In a more empirical sense, by the time the Beatles arrived, New Zealand was a good place to live. Things weren’t perfect. Many women accused their husbands of staying too long at the clubs and pubs. After snaffling a glimpse of life beyond the kitchen sink during the man-powering movement of the Second World War, some women still felt a little aggrieved that such liberation had been nipped in the bud once the men came home. But now with this Beatle invasion there was something stirring again just beneath the surface. Many mothers sensed another round of liberation emerging courtesy of the establishment-challenging, shaggy-haired boys from Blighty. In general, in New Zealand at the time of the Beatle invasion, everyone knew their place, and prosperity stretched right across the social spectrum. There were very few genuinely poor people.

A lot of Kiwi parents were up with the play thanks to television. The Beatles were frequently on the box in Britain. Young people were seen to be getting really steamed up about them. Britain, the mother country, was the setting for early Beatle stampedes and near-riots. When it was announced that the Beatles were coming to New Zealand, some mothers figured they’d be helping out the mother country. New Zealand, the granary, would provide the Beatles with some decent home cooking and a bit of a haircut. After all we were world famous for our topnotch fodder and shearing ability. Back then a couple of the Beatles looked a bit scrawny, and knowing the British passion for jam butties and a lack of veges and dairy products, we would see them right.

Many New Zealand parents were also reassured by a wonderful press photo showing British bobbies (and a couple of bobbettes as well) holding back the screaming fans as the Beatles appeared on some balcony like four Prince Charmings. The policemen and women had big grins on their faces, although their work seemed to be quite strenuous, if not downright dangerous. But that was the Beatles. Everyone seemed to like them, even the coppers who had the unenviable job of preventing mayhem.

And of course the titles and content of their early songs were reassuring too. ‘Please please me’, the first big hit, elicited quaint responses.

‘What nice boys,’ commented a mother who, like most New Zealand parents, admired good manners. ‘They actually said “please”.’

Admittedly ‘I want to hold your hand’ was a bit more demanding, but it wasn’t anything else they wanted to hold, not in the early songs anyway. And despite the fact that thousands of young Kiwi girls harboured fantasies of collecting a real Beatle trophy while they were touring New Zealand, the tight security arrangements thwarted the chance to convert Beatle fantasies into reality. After all, the Beatles were apparently untouchable, unattainable, although tales have surfaced of clandestine liaisons, in keeping with the Beatles’ status as the world’s most eligible bachelors (notwithstanding John’s married condition). But the notion of the Beatles actually stepping out or dating Kiwi girls was essentially fanciful, given the logistics and time constraints of a Beatles tour. ‘Can I take you out to the pictures, Joan?’, the line from ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’, did not represent the way they interacted with the opposite sex in 1964. However, one New Zealander got as close as having a British friend who, in earlier times, could lay claim to a reality that Kiwi girls could later only fantasise about.

All that may have changed a few years later! Change in fact became the operative dynamic in youth culture, for both young men and young women. The rate of change started out slowly, before accelerating. The Beatles, either as benefactors of social change or as the very bludgeons (sociologists were divided on this one), made change fashionable. Music, hair, clothes, attitude. The very status of young people – and of women in society generally – would never be the same.

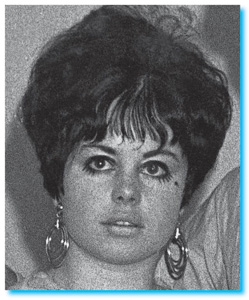

The hairstyles of young women began to change. When you look at photos of Beatle fans screaming at concerts and airports, the predominant female hairstyle is the bouffant, as championed by Helen Shapiro, Annette Funicello and Brenda Lee. Those girls looked quite mature in bouffants. In fact they looked a bit like their mothers. Heaven forbid! The explosion of youth culture, ignited by the Beatles, soon dictated that females let their hair down too, figuratively and in real terms. It was now all about length, or would soon become so. Longhaired maidens, with their hair combed defiantly in the middle, became a product of the Beatle slipstream.

New Zealanders were reminded that the Beatles were as much about hair as they were about rock ’n’ roll. It seemed vaguely silly that the simple business of how you wore your hair could be such a defining phenomenon. But in the conservative ’50s and early ’60s hair length and style, still dictated by the strictures of war and post-war recovery, demanded the regular lopping and chopping of male hair as if there was still a war on. The girls were expected to maintain the bouffant status quo – or something similarly ‘sensible’.

Discussion about the length of hair, fired by the Beatle influence, invariably revolved around practicalities and common sense demanded by Kiwi culture. Long male hair would snarl in rural combine harvesters and urban factory machinery. Long female hair might dangle in an unkempt, undisciplined way into home cooking. It might even become a fire hazard as females slaved over a hot stove or strove around the family hearth to be good mothers and home-makers.

Very soon the feminist movement took flight. It was difficult for sociologists not to see a link between the wild abandonment and emotional release associated with Beatlemania, and the new demands of young women. The swinging ’60s gave birth to the notion that women no longer needed to be ‘shackled to the kitchen sink’. The spirit of youthful female freedom and new possibilities had been ushered in by the Beatles. The invention of the birth control pill, first developed in the 60s, provided the practical wherewithal to break out of traditional female typecasts. The new music may have been emotionally liberating, but the pill and a burgeoning sense of self-belief enabled females to cast off all sorts of shackles.

Sociologists puzzled over the effect a bunch of shaggy-haired Liverpudlian male rock musicians could have had in such a revolutionary swing. Perhaps that’s why they made reference to the ‘swinging sixties’. That the Beatles helped unearth in young women an awareness of their own sexuality was undeniable.

Nights in white vinyl

It was freezing on the train, more so because I was decked out in only a white vinyl coat and black stockings. The outfit had seemed a good idea, especially with the top button missing. I could nearly manage a cleavage but already my stuffed bra was uncomfortable and the metal fastener at the top of my suspender belt had started a ladder.

Mrs Paul McCartney and Mrs George Harrison, a.k.a. Lynne Yeo and Alison Bremner, were leaving Taihape at 11p.m. to go all the way to Auckland to see the Beatles. I had dyed black hair, bouffant style, and teased so it would more or less stand on end, and large ‘doe-like eyes’. ‘Doe-like’, Alison reckoned, because the hard palette of black mascara, when applied with a toothbrush-like appliance, left you with large cakey blobs on your lashes and didn’t allow you to close your eyes.

The Waiouru army boys on the train were suitably impressed by our outfits, but we remained indifferent. We were keeping ourselves for THEM – the Beatles!

I could hardly believe it. With a postal note, Alison had sent away for the tickets. ‘Indifferent Parent’ thought I was going on a biology field trip when I asked if I could go and see the Beatles (she obviously thought I was talking about ‘beetles’), and now we were on our way.

Lynne Peterson, not long after the ‘Nights in white vinyl’.

I don’t know if we slept, but at 7.30a.m. when the train rumbled into Auckland I had that floating, surreal feeling. My feet were already hurting in my stilettos and my ‘Mary Quant’ look was starting to feel a bit lopsided.

Undeterred, we tottered off to our hotel, staring defensively at amused passers-by. After a couple of hours walking in light rain my coiffure was really damaged. We realised we had gone to the wrong place but finally, with me in my greying vinyl and Alison in her mini, we found a likely hotel. We saw a limo which was dutifully screamed at. Everyone else was screaming so we screamed as well. I still don’t know if it was THEM.

Soon we headed off to the mayoral reception and agonised as Paul and John and George and Ringo (so cute) hongied and posed. And then Paul winked at me. He looked straight at me and winked, but Alison wouldn’t listen because she was screaming that George had blown her a kiss.

We could only get into the 6 o’clock show. By that time I had more ladders, my eyes were smarting, I was limping and I’d lost another button, but who cared? The Beatles were on stage now. There THEY were and more gorgeous than ever in real life. All I remember is screaming deliriously, and then it was over...

It’s a funny feeling when you can’t sleep and can’t shut your eyes and you feel excited and wound up. I suppose we would have been awake for a couple of days by the time we got back to Taihape at 4a.m. I don’t think the vinyl (now definitely grey) would have made it much further, the stockings were in shreds, I’d given up on the shoes and all the Capstan Plains we’d been puffing on had given me a very nasty thick tongue.

Alison was staying at our place and the parent got us up to go to school. It was an angry parent in pink housecoat and curlers, who had just realised our journey was not of the biological kind.

I don’t think I took the eye makeup off. I guess that didn’t help our appearance at morning assembly.

Our principal was determined to assert himself. After all it was his first principal’s appointment. Despite our sleep-deprived state, we both knew what we were in for when he dramatically heaved himself forward, clutched his beloved lectern and billowed his black gown ostentatiously behind him.

I can’t remember the biblical text he had chosen to ‘expel us from assembly’, but I know he compared our sins to the very worst heathen acts of the Old Testament. Everything suddenly seemed hilarious: the old goat with his owl glasses and flared nicotine-stained nostrils, the silence, the order to depart. I couldn’t hold it back any longer and started to giggle. So did Alison. Our giggling became uncontrollable as we frenziedly tried to find the part in the curtains to make our exit. I got tangled up and Alison pulled a bit of the curtain down, while old ‘black gown’ bellowed and pointed and gesticulated. Everything just seemed so funny.

We were suspended. ‘Black gown’ had a fag in each hand, sucking furiously, as he announced our punishment. We would not be allowed to represent the school at sport (yay! I hated netball and rompers). We were to make up the time we had lost during our ‘biological trip’ by writing a page from a book each lunchtime, which would not be read but destroyed before our eyes.

Taihape was bloody cold in winter and I got to sit in a warm office and write from Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre, which I could then read in comfort. We weren’t ‘allowed’ to read such risqué stuff, but no one bothered to check what I was reading (and writing).

We were to be demoted to the bottom of the class. More joy. Down there Marilyn McGee could pop out her eyeballs and Edward Te Wiki told filthy jokes. So we became picaresque heroes: the sinners who had gone to see the Beatles. The sixth formers who went to see the ‘Golden Shears’ were apotheosised and we were damned, but how sweet it was to be martyrs for a cause.

And Paul had winked at me. No one could take that away.

LYNNE PETERSON, TEACHER, HAMILTON