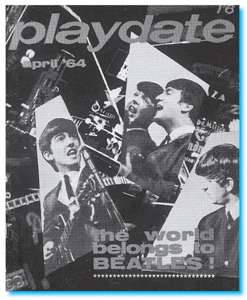

Rising excitement. A Playdate magazine cover, two months before the Beatles’ New Zealand tour.

With the death of George Harrison, in November 2001, the world was reminded again of the sheer significance of the Beatles.

‘I saw the Beatles,’ an unassuming Onehunga shipping executive announced at a family gathering not long after George’s death.

‘Yeah, right,’ replied a cocky, cellphoned nephew with a number one haircut, and a copy of the Beatles 1 CD compilation first released in 2000.

‘It’s true. I was there in ’64. The Auckland Town Hall. The 6p.m. show. George Harrison sang “Roll over Beethoven”.’

It was a bit like saying you’d seen the Second Coming. And it reminded you that sometimes it would be nice not to have newspapers – and media in general – to bring you bad news, like the passing of George (‘All thing must pass’).

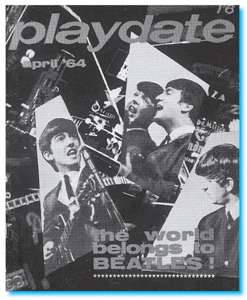

Of course the media had played a pivotal role in sustaining the Beatle phenomenon, so much so that some critics accused the media of stirring up, if not creating, Beatlemania. From a media standpoint, the Beatles, in 1964, were everywhere. In the everyday press and electronic media, on magazine covers as diverse as The New Zealand Women’s Weekly (where their story shared equal billing on the cover with ‘The most popular biscuits ever baked’), to the more appropriate Playdate, the New Zealand magazine dedicated to the reporting of rock ’n’ roll events and recordings.

Daily newspapers had a field day. The Beatles were ‘good press’. Whether they were receiving ‘roaring welcomes’ or being ‘modest and friendly’ at press conferences, the targets of real missiles (eggs in Wellington, eggs and tomatoes in Christchurch, jelly beans and marbles in Dunedin) or imagined ones (bomb scares in Auckland and Wellington), the Beatles were big news. There wasn’t a day of their eight-day tour when ‘matters Beatle’ were not splashed across the headlines of metropolitan dailies and provincial papers as well. In fact, daily New Zealand newspapers had already featured articles and reports on Beatle concerts for well over a year before the band even reached these shores.

It wasn’t just accredited journalists who took up the cudgel. The general public, many of them for the first time, felt compelled to compose letters to the editor:

Sir,

The robes and regalia of a city are the emblems of the toil, aspirations, prayers and evolved dignity of the people of the city, offered over a long

number of years to the purpose of producing a cultured and dignified society. They should not be used frivolously or degraded in the using.

A civic reception should be a mark of honour and esteem paid only to a person of extreme ability, to be cherished as a gesture of recognition by a cultured and dignified people.

I have nothing against the Beatles. I do not like the noise they make, but I recognise the necessary outlets for adolescent exuberance, and providing that they are reasonable, subscribe to them as part of the evolutionary development of the individual. However, to hold a civic reception for any of these degrades the Civic Fathers to the status of capering clowns, and brands the city as uneducated and undignified.

L. WATKINS, AUCKLAND

Sir,

Congratulations to the Mayor of Auckland for insisting that the Beatles have a mayoral welcome. Why shouldn’t the young ones have a chance to welcome their idols? What is a paltry £60 compared to the hundreds of pounds spent on receptions, etc, during the festival?

TEENAGER’S MUM, PARNELL

Sir,

I was thoroughly ashamed of Dunedin as a city when I read it was only with a grudge that a reception for the Beatles was to be given. There is no worry about ‘who’ to invite. An informal introduction to the city as was given to N.Z.’s leading city on Thursday was all that was called for. It obviously reached the ears of the Beatles that the city was going to be put to too much trouble, so they graciously refused any reception.

GEORGE, DUNEDIN

Sir,

Being an ageing spinster with radiophobia, I have never had the pleasure (nor the anguish) of hearing the Beatles except in snatches, but the photo in

The Dominion of 23 June, of teenagers in the Town Hall beating time with radiant glowing faces, has disposed me to be more Beatle-minded, for

the same reasons as were expressed by ‘Middle Aged’, seeing in them avantcouriers of a happier form of self-expression and (in England anyway) of bad conditions of yesterday.

One cannot change in one generation what has been in the making for centuries. When the fever of release cools down, they may or may not tune a quieter ear to Liszt or Chopin. They are much preferable, one might feel, to the faltering, pathetic little snobs whose mothers have convinced them of a taste for highbrow entertainment before they are able to saturate it or even understand it. Better an honest love of the Beatles than a dishonest love of Chopin.

As to the Beatles’ hairdo, it has poetry and grace. The beating of the drums is no more savouring of the jungle than the heaven-help-you-if-you-live-outside-the-tribe attitude. There are surely greater causes for indignation in the world than what people do with their own hair.

U.S. BEESON, WELLINGTON

Sir,

The Beatles are apparently capable of attracting a near-capacity house at each of their two sessions (6p.m. and 8.30p.m.) at a price varying from 25s to 50s for adults. One wonders where the musical ‘taste’ of many of our people is when the Beatles with this type of ‘music’ can command audiences as mentioned, while many genuinely talented combinations with music of a more mature nature can command only a partially filled hall. Apparently our modern generation which is anxious to decry the merit of other tastes, is proving to be as susceptible to high pressure publicity as ever. In the past it has been proved that this ‘popular’ music has a short life, while ‘mature’ mellows with age.

R.W. WHITE, CHRISTCHURCH

If views were polarised in letters to the editor (of which the above is a fair sample), then opinions regarding the Beatles were also divided in the more arcane encampments of quality journalism and comment.

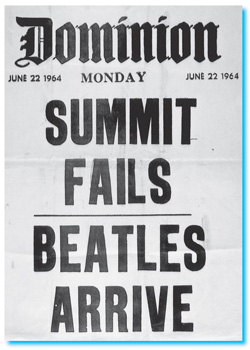

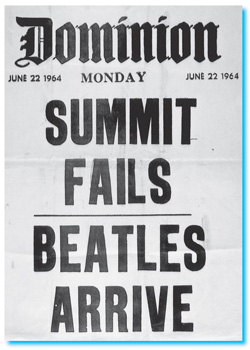

Well they have come and gone, the most fabled young men in the world. Ten thousand throats are raw, a thousand tear ducts dry. A two-day state of siege is lifted in the cities, policemen return to more usual ‘beats’, and the hearts of the young are heavy with loss. The extravagance is hardly too lush for an event, celebrated unforgettably by Wellington’s morning billboard: SUMMIT FAILS/BEATLES ARRIVE.

What is their secret? Why does each of these young men earn as much in a month as a Prime Minister in ten years? Why, all over the world, do strong girls scream and weep? What is being liberated? Many have tried to answer and all have failed, even the most distinguished and learned. The boys themselves decline to comment, wisely; their progress has been intuitive and if they could explain it, they would not be where they are. Perhaps, then, their secret has nothing to do with learning and distinction; perhaps anyone has a right to his say. Here is mine.

First, a personal digression. Last August I was abroad, and thinking fondly of my elder daughter, sought to tell her what was with it in the British pop world. I sat solemnly through sessions of Juke-Box Jury on TV and noted the hits; read the popular press, kept my ears to the air and to the ground. I dutifully reported my researches, and commented as follows: ‘The most popular group here at the moment seems to be the Beatles. Have you heard of them?’

Her reply was blistering. ‘You are,’ she wrote with acid affection, ‘the most complete * in the business!’ Crushed, I returned in December to find her wallpaper obliterated by huge portraits of John, George, Paul and Ringo; her bookcase stacked with magazines exclusively devoted to them; her shoes all mysteriously pointed; her drawers stuffed with weird trinkets; the radiogram never free of the decisive (for it is nothing, if not that) Mersey Beat.

I am now with it. I know every word of their recorded songs, every plangent thrum of their guitars, every detail of their lives, what they say, what they read, what they eat, what they think. It has been no effort; with my household rocking to the beat and littered with the icons and mythology of the cult, it has been as painless as osmosis. And, like many thousands of others, I have at last seen them on the stage, watched them

in action and knew, from time to time, which songs they were performing, when my daughter and her thousand-throated friends drew breath. These are my credentials for what follows.

All is not lost. A newspaper headline heralds the Beatles’ arrival.

First, I sense a deep satisfaction in their being a quartet and not a trio, or a quintet. For many centuries, our culture has insisted, in its rituals and mythologies, that if human destiny is represented by a trinity, it is most justly expressed in action by a quartet. The four Evangelists, the four temperaments of medieval philosophy, the four traditional characters of early Italian comedy, soprano, alto, tenor, bass in song and opera. The quadrilateral in motion is somehow intrinsic and basic. The Beatles are, I would say, perfectly poised one against the other, not in opposition, but in fruitful counterpoint. John is the dependable leader, firm of mien, fixed of purpose, feet gripping the stage and barely moving; Paul is the pleasant boy from next door, alert, appealing, mercurial and light footed, in this for a lark; Ringo is the farthest out in every sense, set back from the others at his drums, an air of sometimes raffish melancholy on his face, eccentric and with his rings, conveys a whiff of the exotic; George is the dark horse, the ‘common man’ of the group, as someone suggested to me, bridging the gaps in the spectrum, moving solicitously between John and Paul, singing now with one, now with the other, watchful, considerate.

And I detect in the group a multiple ambiguity, amounting to paradox. Their name, for example, Beatle is perfect, with its play on the most homely and harmless of insects; who could imagine them spiders, newts, scorpions or caterpillars? Then there is the cross-fertilisation from Beatnik, the Beat generation, perhaps a glance towards Beatitude, to which we can surrender in their presence, to say nothing of the Mersey beat itself, with its challenging and characteristic zing and clang.

Although their appeal not only crosses frontiers but language, with screams as piercing in Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Hamburg as in London, New York or Sydney, they remain unaffectedly provincial, speaking with the sturdy accent of their town and shire. Their personalities may light fires in a million young hearts, but when the demi-gods arrive, they speak of homely matters: of family, of food, of Mum and of Dad. Where their audience is frenzied, they are cool and controlled, running their routines

calmly (if not quietly!), and where many of their young fans affect garish colours and outlandish designs, the Beatles are immaculate and sober in their dress. They might be the newly appointed prefects in a very exclusive school of graduates in the charm section of the Foreign Office, if it had one. The Phantoms of the first half yelled and gyrated in shimmering blue lamé: Johnny Devlin, fiercely energetic, invited multiple dislocations in a costume poised somewhere between trick cyclist and Martian visitor – the contrast with The Beatles’ cool sobriety of manner and dress could not be more glaring.

Against this sobriety works the startling ambiguity of their shocks of hair. Does their strength, like Samson’s, lie in it? Yes, it partly does, I think; it’s their gimmick and sign, the symbol by which they can be represented and recognised all over the world. And by growing it, they have violated one of the most cherished taboos of the Anglo-Teutonic male, to whom, for over a century, long hair has been the symbol of the arty non-conforming pansy. Why this should be so is probably deeply rooted in Puritan psychology; it certainly explains the abortive attempt to storm the Hotel St George in Wellington for a shearing exercise, to say nothing of Howard Morrison’s ‘I wanna cut your hair’. Every true-blue New Zealand male will wanna cut their hair because, somehow, it challenges him.

In their music itself, I find ambiguities. Although noisy and frenetic in style, in sentiment it is often tender, consoling, conciliatory. Affectionate letters pass between lovers, those estranged are persuaded to make friends (‘Yeah Yeah Yeah!’), money can’t buy you love. Corn? All right, but unexceptionable, worthy, harmless. Are they first-rate musicians? I wouldn’t know precisely.

Their style is individual and unmistakable and I agree with that critic who, tongue in cheek or no, found the shape of their melodies, modal. Some of their tunes veer between major and minor in an arresting way and modal is probably the term for this. Their skill is of the order that invites an orgiastic response (which it surely gets!) rather than wide-eyed goggle at their musicianship. The overwhelming response to the Beatles suggests that our straight-laced society offers little opportunity for passionate and spontaneous feeling. This the boys accept with grace and tact; their

splendid unison bows of Oriental depth, complete their highly finished presentation.

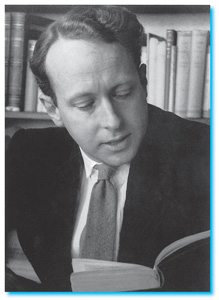

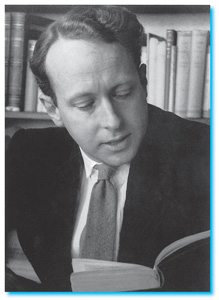

New Zealand playwright Bruce Mason: ‘I salute them [the Beatles] as gear and fab.’

I find a further startling ambiguity in the leader of the world’s number one pop group, writing a book in the style of a Joycean word play, as if Alice in Wonderland had been strained through Finnegan’s Wake and stuffed with chillies. In His Own Write is a slim work of poems and sketches, by turns sharp, hilarious, witty and obscure, but it never reveals John Lennon as ‘a pathetic near-illiterate’ as the British MP recently said, thus possibly securing his only chance of immortality. John claims, I am told, that he has never read James Joyce and was no way influenced by him. Just a moment. Here is John from ‘You might well arsk’. ‘Why did Priceless Margarine unt Bony Armstrove give Jamaika away? You might well arsk.’ And Joyce, Finnegan’s Wake, p.14: ‘What means the saloon slogan Summon In the Housesweep Dinah?’ You might well arsk again. Lennon, from ‘The Wrestling Dog’. ‘Once upon a tom in a far off distant land far across the sea miles away from anyway over the hills as the crow barks 39 people lived miles away from anywhere on a little island in a distant land.’ And Joyce, p.152: ‘Eins within a space and wearywide space it wast ere wohned a Mookse. The onesomeness was alltolonely and a Mookse he would a walking go.’ Ad leased Long John Lennie ist Missedher Joyce’s faceful disciplinall. Thair issed fur moor in theas boyce than emits the furst glans.

Have I made my point? Multiple ambiguities, a consistent fuzzing, doubtless quite intuitive, of accepted images. But none of this matters a damn to the young. They don’t sift or analyse; what need meaning when they are immersed in the flood or swimming on the tide? Is it sex? Cautiously, I beg to doubt it. The Beatles are a group, not Elvis, not Cliff, and the group is indivisible. The music? Only partly. As well if you know it by heart, because the fans don’t want to listen but yell with joy. This is what I feel the Beatles offer: a uniquely constructed, original bridge between adolescence and the confusions of the adult world. They are not angry young men, present no facet of hostility to anything. They have constantly to deal with the authority, as the young will also, in a few years. How? With a bland assurance. If a Duchess comes to their show, she is required, not to display, but rattle, her jewellery. Even Duchesses are people, they

seem to proclaim. Priceless Margarine (this is likely to stick, I feel) is one of their greatest fans. In other words, they deal only with people, never with functions. The British Ambassador in Washington or a kid with an autograph book: both are people, both entitled to their respect. Consequently, their irreverence is never insolence: they have no attitudes to strike or maintain, being content as they are. I find this fruitful, I find it remarkable, I salute them, as gear and fab.

BRUCE MASON, WRITING IN THE NZ LISTENER

Almost any group of people with passable voices can be groomed for success by the entrepreneurs, the big fellows in the background who go on making money when their ‘discoveries’ have returned to obscurity. Their choice could just as easily have fallen on the Katipos or the Huhus, if those groups existed; and next year, or the year after, the lightning will strike again. It is a strange popcorn world in which talent is strictly relative and genius an embarrassment.

Youth must now and then break through the restraints we impose upon it, and it is better done vicariously, in a concert hall, than elsewhere in violent actuality. ‘Yeah’ is not the best way of saying ‘Yes’, but it is probably the loudest, and if for a moment we could hear it through young ears, the singers shouting and the audience in ecstasy, it might cease to be merely an animal noise and become instead a joy in being alive, a cry of affirmation, that only the young can fully understand. We do not propose, however, to carry this tolerance – or brief infatuation – to a sacrificial pitch. It is our hope and indeed firm intention that, having heard the Beatles once, we shall not hear them again.

M.H. HOLCROFT, EDITOR, THE NZ LISTENER

Within their own circles, New Zealand Beatle fans began using words like ‘fab’ and ‘gear’ and other scouse colloquialisms favoured by the Beatles. A certain irreverence based on the Beatle model crept into everyday conversation. ‘Cheeky brats’ and ‘loud mouths’ came out of the woodwork.

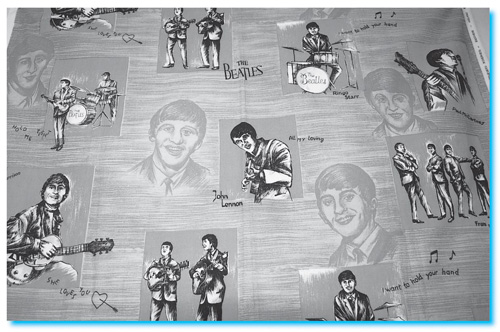

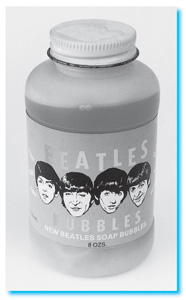

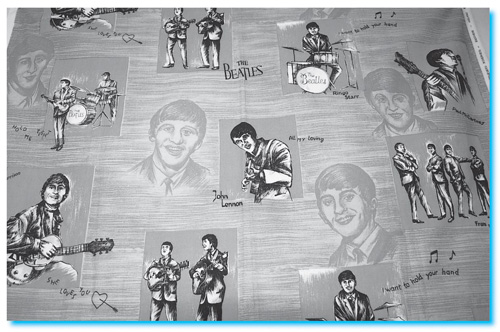

Out in the commercial world, cashing in on the phenomenon kicked in quickly. You could buy products as diverse as stockings and tea towels, with Beatle motifs and likenesses attached in some way to the product in question. Did having Beatle tea towels in the average New Zealand household mean that teenagers were becoming more inclined to dry the dishes? Not necessarily, although such a sea change would have been more likely if young dish-driers were obliged to dry the Beatle mugs that soon became available.

Many teenagers decorated their bedrooms with Beatle curtain material.

Beatle wigs, both plastic and expensive fur adornments, became popular, often as a gag to wear to the burgeoning Beatle parties that broke out in the wake of the ’64 tour. Even old Davy Crockett coonskin hats renewed their sales cycle – as ‘Beatle wigs with tails’ – or were coming out of the closet long after their original mid-50s use-by date. And it wasn’t just the younger generations who were swept up in the spin-off frenzy. Middle-aged New Zealanders and balding men took a fancy to imitation hair Beatle wigs.

Beatle handbags, frocks and jewellery were popular with female shoppers, as were suede boots bearing the ‘ladybird’ emblem. The distinctive winklepicker shoes and boots favoured by the Beatles became popular with males, although Kiwi Beatle blokes would never own up to the fact that such constricting footwear was often uncomfortable. Another painful aspect of Beatle accoutrements occurred when young men sporting genuine Beatle haircuts had their manes yanked by misguided females who figured they were wearing Beatle wigs.

Beyond such product ranges, the mere association of the Beatles tag permeated the commercial heart of New Zealand. ‘Exclusive Beatle portraits’ were available from Atlantic service stations, in settings where, no matter how you looked at it, the purveyors could not get away with selling ‘Beatle petrol’. Beatle posters, calenders and postcards were offered as inducements in many commercial outlets. A record shop in Auckland, while obviously selling the very items that had set off the spending frenzy in the first place – Beatle records – also offered free autographed Beatles’ photos – and free Fanta soft drinks. It has been rumoured that Beatle toilet paper, and other less glamorous products, were on the drawing board until the commercial powers-that-be called a halt to the more bizarre spinoffs.

And of course the New Zealand recording industry was not slow in releasing songs dedicated to, or depicting some aspect of Beatlemania as it impacted on New Zealand. One of the most successful ‘tribute’ recordings of 1964 was ‘My boyfriend’s got a Beatle haircut’, sung by Rochelle Vinsen, a 17-year-old Wellington training college student. The song had been a minor hit for American songstress Donna Lynn, but in the Beatle-besotted British outpost that was New Zealand in 1964 it shot up the charts.

Wellington band Tony and the Initials (a group with a very pre-Beatle name) released ‘Beatle bridge’. Dinah Lee chimed in with ‘Yeah, yeah, we love ’em all’ and the Howard Morrison Quartet, feeling threatened or simply culture-shocked, put out a parody, ‘I wanna cut your hair’, which was not as tongue-in-cheek as history would have us believe.

Away from the glare of commercial hype, an unknown Wanganui jam-band wrote a down-the-hall-on-a-Saturday-night type of dag-dusted ditty called ‘Don’t beat the Beatles’. Today the reel-to-reel recording of the song sounds as bad as it probably did back in ’64, with its uneasy fusion of country and western, eastern polka and ham-fisted interspersion of rock ’n’ roll backbeats. Ringo may have been able to make sense out of it, but the rest of the western world turned its back when it was earnestly presented as a serious recording proposition.

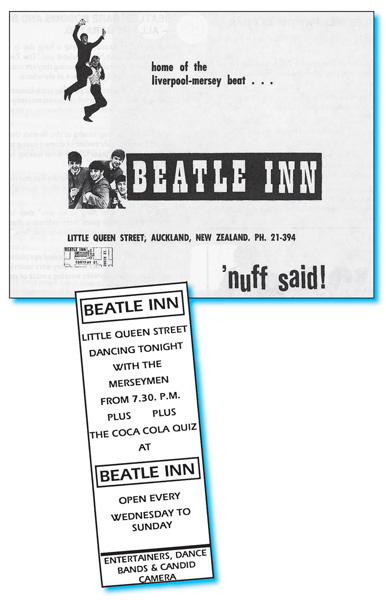

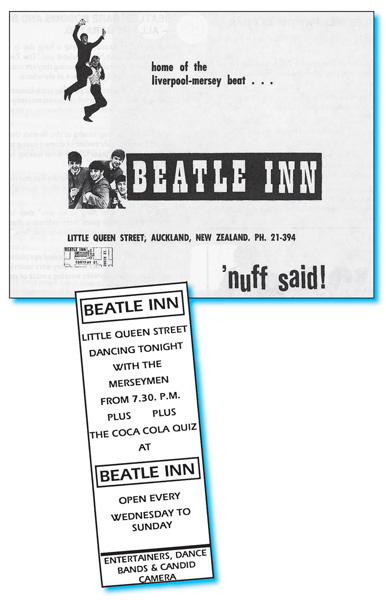

Back in the glare of commercial hype and urban opportunism, Phil Warren, the Auckland promoter – the man who had in effect unearthed Johnny Devlin as a New Zealand recording phenomenon – set up the Beatle Inn, a music club in Little Queen Street. With space for 300 revellers, the club cashed in on the Beatle craze, even cobbling together a resident band, the Merseymen, who thrashed out Beatle covers and generally did their best to project the image of the ‘Cavern’ club, Liverpool. Bob Paris and the late Dylan Taite (known then as Jet Rink) were band stalwarts and the club boasted an R18 rating, meaning that revellers over the age of 18 (‘Well she was just seventeen’) were not permitted entry.

Phil Warren cashed in further by publishing the Beatle Book, which sold about 5000 copies during the Beatles’ tour. Warren had been able to use the name ‘Beatles’ quite legally and utilise photos because the Beatles themselves (or more specifically, Brian Epstein) had not yet officially registered their name.

In such a Beatle-inspired shopping spree, there were bound to be casualties. As has already been noted, barbers suffered. Many young men simply stopped having their hair cut. Others turned to their girlfriends to tend their teeming manes, aware that traditional barbers, representing the forces of the establishment, would hack into their undisciplined locks with scant regard for the new forces unfettered by the Beatles that suggested – and then demanded – that long hair on males was now OK.

If barbers and other New Zealanders threatened commercially by the Beatle wave drew a sigh of relief when the Beatles departed New Zealand, figuring that that would represent the end of the Beatle ‘fad’, they would soon be hyperventilating again. The release of the Beatles’ first film, A Hard Day’s Night, was destined to feed the ‘fad’.

And if conservative editors thought the Beatles, in terms of column inches in newpapers and magazines, would fade, A Hard Day’s Night ensured that the New Zealand media had no choice but to continue chronicling the Beatle phenomenon. It appeared to be no ‘fad’.

A hard day’s night was guaranteed for all.