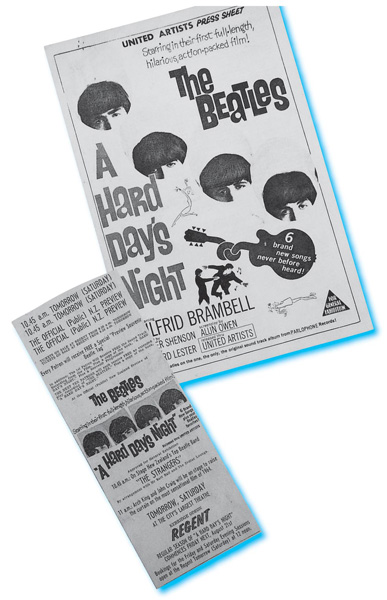

The Beatles came to New Zealand in celluloid form in 1964. Their much-heralded and long-awaited movie, A Hard Day’s Night, was released on 15 August, a couple of months after their concert tour. Sixteen theatres in 16 cities throughout New Zealand screened the iconoclastic movie at the same time.

While this coordinated screening was described as a ‘special preview’, the real thing occurred some days later, on Friday 21 August – the beginning of the film’s regular season. Never before in the history of motion picture distribution had 16 prints of the same film been released simultaneously.

For many Kiwis the release of A Hard Day’s Night represented the next best thing to being at a Beatles concert. For those who had been lucky enough to see them in the flesh, the movie was further confirmation that the Beatles, quite suddenly, had taken over the world – in terms of mass-media communication.

Our very first 45 was ‘A hard day’s night’, given to my sister Frances and me by our parents, along with ‘If I had a hammer’ by Peter, Paul and Mary. We really can’t remember why we were bequeathed these, as there was little music in our house and our mother has always had a tin ear and ‘nil musical appreciation’. We overheard her talking to a neighbour and saying that she ‘hoped they would wear it out soon’, after constant playing on the turntable.

I was able to convince my mother that it would be safe for me to go to the film, A Hard Day’s Night, with two female acquaintances, wearing my trusty red duffel coat. My sister Frances cried because she couldn’t go too, even though she owned Beatle boots and was known as ‘Beatle’ at school because of her hairstyle. Frances thought the Beatles were particularly wonderful.

Both Frances and I remember seeing the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show, but most of the time it was a matter of finding out about them through second-hand knowledge. I had the chance to read girls’ magazines on Girl Guide camps, magazines I wasn’t allowed at home. I remember having to fight even to see Cliff Richard in Summer Holiday.

JOSEPHINE MAPLESDEN, SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHER, HAMILTON

Princess Margaret and Lord Snowden attended the London premiere of the movie and most reviewers, including royalty, were loud in their praises of yet another artistic triumph for the lads from Liverpool.

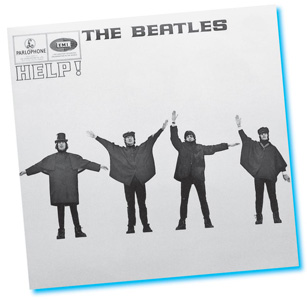

The movie, rather surprisingly, was a black-and-white affair, which if nothing else, was in keeping with the cover of their last album, With the Beatles. It was entirely representative of the Beatles at their monochrome stage. Later creative efforts would see the fab four in stunning technicolour in the sunny Bahamas (their second movie Help!) and kaleidoscope flashes (the cover of Sergeant Pepper).

The immediacy of the Beatles was in evidence again. The globality of the phenomenon. Just as many of their recordings were released as simultaneously as possible throughout the world, so A Hard Day’s Night was put out there in a ‘saturation bombing’ style of mass culture exposure. Brian Epstein had said virtually from the outset that he wanted ‘his boys’ exposed to the world with an urgency that would make their appeal instantaneous and the product immediately accessible. None of this drip-feed approach adopted by the purveyors of the Elvis product. That may have increased the mystique but it did little to satisfy the craving fans. Beatle products were ‘at your store now’ or in local theatres before you could even ask your parents if you might be permitted to attend.

In cities around New Zealand interest in the film was profound. A young man from Brooklyn, Wellington, was the first Beatle fan to form the head of the queue outside the Regent Theatre. In scenes that mirrored the gatherings of pre-test match rugby queues, the Beatle-fringed fan took up position at 3a.m., more than seven hours before the theatre doors opened. Such behaviour, in respect of movie queues, was unheard of in New Zealand. No one queued like that for Rock Around the Clock or G.I. Blues.

The only company early queuers had for the first couple of hours were members of the police force. In the upbeat mood of the times, it was reasonable to suppose that the police were hoping to get a good seat at the Regent too. After all, they wore uniforms just like the Beatles. By the time the theatre opened at 10.15a.m. the queue had grown to 350, an excited, seething beast that snaked around Cuba Street for thirty metres – the average length of a Don Clarke penalty goal.

Once New Zealand Beatle fans and curious Kiwis got to see A Hard Day’s Night, they found a slick, often brilliantly directed slice of controlled celluloid chaos, that depicted the Beatles going through the rigours of being Beatles, before presenting a concert that featured, not surprisingly, Beatle songs. A whole raft of them. Brand new ones. In the process, director Richard Lester was able to reveal the individual personalities of the four Beatles, while presenting in mock-documentary style the phenomenon of Beatlemania.

We saw the movie in Christchurch with a mate who, while not a true Beatles fan, was prepared to admit that something significant was unfolding in popular culture. A man behind us stormed out half-way through, but it had nothing to do with anti-Beatle feelings. It was simply the fact that the movie was so fast-paced, the images so teeming, that his programmed senses couldn’t keep up. In fact they reckon he did a bit of a swoon as he groped around in the darkened aisle.

Females were screaming. Some of them had to be escorted to the foyer. We figured it would be fertile ground for a psychologist to study the behaviour of young women in response to inanimate objects, which the celluloid Beatles were. You could perhaps understand them screaming at the concerts – reacting to animate objects – but losing everything in a darkened cinema smacked of forces we males didn’t understand.

If you blinked you missed something. I think I blinked a couple of times, and saw fit to see the film a second time. My mate saw A Hard Day’s Night four times, at the end of which he was totally converted. He thought the Beatles were the greatest comedians since the Marx Brothers, particularly John and Ringo. It took me some time to remind him that the Beatles were a rock band, not movie actors as such. Their personality, wit and camaraderie came across big time on the big screen.

While the Beatles were in New Zealand they nominated a McCartney ballad, ‘And I love her’, as the stand-out track from A Hard Day’s Night. In retrospect, such a judgement may have been tongue-in-cheek. ‘And I love her’ was the sort of song that the establishment would feel comfortable with. It was pure, love-above stuff, full of positives and love that will never die. The backing was understated, with none of the electric thrash that had propelled the Beatles on to the world stage. It was Paul’s home-made ‘A taste of honey’ and ‘Till there was you’. It was good, but some of the other tracks were more representative of the escalating development of the phenomenon that was now coined ‘Beatle music’.

In fact John was the dominant voice in and on A Hard Day’s Night, the movie and the album. The title track, a John song, apart from the Paul bridge, became a massive worldwide Number 1 hit. You heard it everywhere on jukeboxes throughout New Zealand. From Temuka to Te Puke, George Harrison’s striking opening chord riveted Kiwis to the spot. Then John Lennon’s dominant doubletracked voice punched out the anthem. Even the cunning wordplay, (the title A Hard Day’s Night made no literal sense at all) was assimilated rapidly into the argot of the day. Central Otago shearers admitted over bottles of Speights to having had ‘a hard day’s night’ after shearing a million sheep. King Country freezing workers, who might otherwise have regarded the Beatles as ‘girls’, confessed in the public bar to having had a hard day’s night’s butchering. Auckland stevedores, the same. At one stage someone reckoned ‘A hard day’s night’ became the working-class anthem in New Zealand, and before too long it was being trundled out alongside ‘Hoki mai’ and ‘Jailhouse rock’.

‘I should have known better’, another John Lennon composition sung entirely by John, and featuring his distinctive harmonica-playing, was almost as earcatching, while ‘Little child’, off With the Beatles, with its exuberant singing and affirming subject matter, continued the notion that the Beatles were intent on peddling happiness. True, it was love-above stuff too, but delivered in such a boisterous, boyish manner – laddish almost – that it made ‘And I love her’ seem the preserve of the sissy. And Kiwis couldn’t abide sissies. Perhaps it was the timbre of the two voices – John’s and Paul’s. Someone reckoned John sounded like an All Black singing at an after-match function; Paul came across as a choir boy – or Vic Damone.

The third track, ‘If I fell’, has long been regarded as one of the best Beatle songs. After a somewhat terse intro by an unaccompanied John (‘and I’ve found that love is more than just holding hands’), a glorious two-part harmony with Paul carries the song to the heights. The gauche sentiments of ‘I want to hold your hand’, having been debunked in John’s intro, are further buried in a ‘words and music’ stream of consciousness that suggested that Lennon-McCartney love songs were evolving into mature statements about the reality of relationships and the bitter possibility of rejection and pain, commitment and insecurity.

George Harrison sang the next track, ‘I’m happy just to dance with you’. After ‘Don’t bother me’, his stand-out composition on With the Beatles, everyone expected George to sing one of his own songs, but such was the momentum of the Lennon-McCartney machine – and the egos – there was no time for George’s apparent doodling.

John, predicably, wrote ‘I’m happy just to dance with you’ specifically for George to ‘have a sing’. It was such a good song that Anne Murray, the Canadian songstress, later produced a version that highlights all its vocal and structural nuances.

The screams, the dervishness that greeted George’s turn in the vocal spotlight revealed his massive popularity. In New Zealand, at least, George Harrison was often the most popular Beatle, the quiet, cautious youngster who appealed to Kiwis because he seemed to lack the attention-seeking antics of the other three – certainly John and Paul. Not that we felt sorry for George. Not all the time anyway. But there was something in the way he moved between the two giants, John and Paul, something in his gracious reticence that convinced us that George, the epitome of the Kiwi ‘boy next door’, was more like most young New Zealanders than the others.

After all, the Beatles were Poms. In New Zealand we’d experienced the young braggards and big mouths shipped here from the mother country. Some of them continued to remind us that we were colonials. At one stage John Lennon and his merchant seaman father Fred were famously going to immigrate to New Zealand. A quick double-take of that scenario would have produced the notion of the Lennons as ‘Poms in New Zealand’, with all the swagger and pugnacity – and cleverness and cruel wit – that has sometimes been associated with British migrants.

Ironically it was George Harrison, the quiet artisan who would not have seemed out of place on a South Island high country farm, who announced after the Beatles returned to Britain that New Zealand was a ‘pretty dead place’. It reminded him of eighteenth-century England.

So George in and on A Hard Day’s Night was happy just to dance with you. Then came Paul’s ‘And I love her’, followed by a marvellous, manic three-part harmony gem called ‘Tell me why’ that was essentially another song written mainly by the precocious Pom, John Lennon.

To add a semblance of balance, the all-Paul ‘Can’t buy me love’ completed the A-side of the album, a side that contained the songs that could be accommodated, time-wise, in the movie. That meant a further six songs, an entire album’s B-side, could not find a home in the ground-breaking movie.

As a consequence, there was a tendency at the outset to be a bit dismissive of side two of the Hard Day’s Night album. But in the opinion of many Beatles sages the songs on the B-side, those not included in the film, took on an aura of their own. They were Beatle ‘rejects’. A rich man’s out-takes.

The claim was made that the songs featured in the film were more commercial – and conventional. This is a ‘happy’ song, (‘I should have known better’). Here comes the ‘slow’ one (‘And I love her’). The next one is George’s turn (‘I’m happy just to dance with you’). But the balance of songs on side two represented an outstanding body of work. A bit darker, more moody. Apart from ‘Things we said today’, a minor-chord, Paul classic – better, many ventured, than the A-side’s equivalent, ‘And I love her’, it was nearly all John Lennon’s work: John, the dominant rock hard man, influenced already by Bob Dylan, and harking back to diverse personal icons like Wilson Pickett (‘You can’t do that’) and Carl Perkins (‘I’ll cry instead’). Paul barely got a look in at that stage. George just played his guitar – brilliantly – and added intriguing touches like the ringing twelve-string accompaniment to ‘You can’t do that’.

When Kiwis first heard ‘When I get home’ and John sang the line, ‘I’m gonna love you ’til the cows come home’, some of us thought, in our bucolic naïvety, that John was somehow dedicating the song to New Zealand and our dairying heritage. Some hope. ‘When I get home’, like all the Hard Day’s Night tracks, was recorded long before the Beatles ever set foot in that far-flung foreign field, New Zealand.

There was an edge to everything. The guitars, Ringo’s drumming, Paul and George’s slightly manic second- and third-part harmonies and John’s lyrics. ‘I’ll cry instead’, which was eventually released as a single, commenced with the sentiment, ‘I’ve got every reason on earth to be mad...’, which sounded like a cry for help, an acknowledgement that the madness of Beatlemania, from the inside, was taking its toll.

The learning curve had been steep. While you could hear the Carl Perkins influence in ‘I’ll cry instead’, it was staggering to realise that the last Perkins song covered by the Beatles before A Hard Day’s Night – ‘Matchbox’, sung by Ringo on the ‘Long tall Sally’ EP – was a few short months ago. Lennon, the pupil, had outflanked the teacher. A wise old outback Beatle prophet suggested that ‘I’ll cry instead’ sounded as if it had been written for Ringo. After all, Ringo played no vocal part in A Hard Day’s Night, and that became one of the few disappointments. Furthermore, Ringo would have introduced an element of tragic humour had he been entrusted with the line, ‘I’ve got every reason on earth to be mad’. John, the serious talent, sounded thought-provoking if not a little scary.

Thought-provoking, scary even. Even as A Hard Day’s Night, the movie and the ‘commercial’ songs on the album celebrated the ‘happy’ aspects of the Beatles and Beatlemania, there were now tangible signs that happiness was not just a warm hotel room in Dunedin. Through their evolving music, the Beatles would soon be touching on aspects, good and bad, of the human condition itself.

For Beatle fans, A Hard Day’s Night cemented every dream half-realised by the 1964 Beatles’ tour. The movie now enabled fans to put faces to the mop-topped apparitions seen fleeing to waiting cars in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin. It was now possible to hear them speak and sing, although God knows there were still a lot of distracting shrieks in movie theatres throughout New Zealand. A Hard Day’s Night, the album, confirmed for serious Beatle music lovers that Lennon-McCartney were the greatest rock songwriters of all time. To some extent Lennon-McCartney had been marking time creatively, as they conquered America and travelled to the antipodes. ‘Long tall Sally’, the EP, released between With the Beatles and A Hard Day’s Night, contained no new original material.

A Hard Day’s Night was to become the only Beatles’ album containing solely Lennon-McCartney songs. As such, it remains a priceless treasure. A Hard Day’s Night, the movie, so captivated New Zealanders that it was little surprise when opportunists in America threw together The Monkees TV series, an unabashed ripoff, or back-handed tribute to perhaps the most remarkable rock film ever made.

Once again the Beatles had got it right. Even the tag A Hard Day’s Night was perfect. And to think that the title was based on a throwaway conversational line by Ringo – of all Beatles. Well, it made you think, that’s all.