When you think about it, for many New Zealanders it really was just the music – initially. Someone said the Beatles sounded just like any other band. When you got over the sacrilege of such comments, the analysis set in.

‘Love me do’ and ‘From me to you’ were good but not extraordinary, but ‘Please please me’, ‘She loves you’, ‘I want to hold your hand’ and ‘Can’t buy me love’ were songs the like of which hadn’t been written yet. And then there was the playing. As a combo they stood alone. You could hear that in their New Zealand concerts – occasionally. The beat was huge, and although any band can turn up the volume, the individual playing styles somehow melded into a very distinctive rock ’n’ roll format. At times it was clank and throb. It was very electric. John’s rhythm guitar on ‘I want to hold your hand’ had a menacing thrust to it. Perhaps that’s why the birds went wild. Paul’s bass run on ‘I saw her standing there’ was a melody line in itself. And George turned ‘I call your name’ into a distinctly Beatles statement with murderous guitar phrasings.

The early explosion rode on the back of these factors. Along the way hair, suits, sex, films and controversy entered the mix, but for many it was always the music. In New Zealand, as everywhere, we hadn’t heard anything that good before. Simple.

‘They were just chords, like any other chords,’ John Lennon once said, in apparent refutation of his own unique talent. Some New Zealanders tended to disagree. Shelby Grant, a private, registered music teacher of Wellington, a musician who has sharp recollections of the Beatle phenomenon, was also able to make significant interpretations of Beatle music. At a time when British musicologists were perhaps reading more into Beatle music than the Beatles themselves were prepared to admit or acknowledge, Shelby considered there was something in the so-called ‘aeolian cadence’ harmonising the melody line of ‘Not a second time’, a distinctly John Lennon rock ballad off With the Beatles. By humming the melody and the tumbling notes devised by Lennon – set to the basic accompaniment of hand on thigh – Shelby was able to highlight the tune, which in such a barren setting, sounded for all the world like an Arabian dirge. Which made sense given that the term ‘aeolian’ harked back to Arabic influences. You could almost smell the camels and sense the date palms wavering in the hot desert wind.

In general, members of the New Zealand music scene, particularly those with formal training, were overwhelmed by the Beatles’ unconventional approach. Because the Beatles had had no formal training of their own, their approach and finished product were utterly original. Their melodic and harmonic constructions were instinctive. No one had told them not to play and write and sing the way they did, and their genius was able to flower. George Martin, their record producer, a man with much formal training and knowledge of how music should sound, was also able to recognise the raw talent and rare instinctiveness of his charges. The Beatles might have been breaking the rules, but to them – and George Martin – it all sounded valid and exciting. A less astute and less trained producer might have missed the boat – and the point – of Beatle music.

Informally, too, a lot of New Zealand fans began poring over the songs. Some became very interested in Beatle nuances, and analysis of Beatle harmonies became popular. There were a few oddities. Someone noticed that when John and Paul harmonised on the chorus of ‘I saw her standing there’, all was going well until John seemed to be unable to find a harmony on the last word, ‘there’, so he just sang unison.

Questions were also raised regarding John’s apparent ability to play the harmonica and sing at the same time, but by now he was overdubbing one on the other. Some years ago a rare live version of ‘I saw her standing there’ surfaced on an obscure CD called For No One. The artefact featured tracks the Beatles themselves contributed from their private collection (or so the accompanying liner notes claimed). It was thrown together long before the Anthology phenomenon. On this version of ‘I saw her standing there’ John played harmonica so much that it seems unlikely he was playing rhythm guitar at all. This apparent lack of rhythm guitar highlighted the all-pervasiveness of Paul’s bass line that held the sound together.

It was unusual for a bass player to be so up-front in those days. It showed what Paul, the bassist, was capable of. In the early years his bass was often sublimated by the guitars of John and George, but it wouldn’t be long before Paul’s bass became a dominant instrument. Later tracks like ‘Hello goodbye’ and ‘Lady Madonna’ featured bass as a driving force. It wasn’t just the fact that it was turned up loud in the mix. What he was playing – the notes he was hitting – was extremely inventive.

Although such displays of individual brilliance could be highlighted, it was the cohesiveness of the band that took many fans’ fancy. And their amazing ability to write a seemingly never-ending supply of really catchy tunes.

I remember being at a party in 1964 and an incredibly happy song came burst-ing out of the gramophone. It was obviously the Beatles. The voices and harmonies gave it away. Was it their new single? I hadn’t heard ‘Can’t buy me love’ yet, which was, according to one camp of followers, already on the airwaves and in the record stores. Obviously, I figured, that’s what the new happy song must be ‘...and all I’ve gotta do is thank you girl’, went the chorus. Wrong. It was ‘Thank you girl’, the other side of ‘From me to you’. I played the track all night, or until such time as some drunken short-hair considered he had heard enough. It was hard to comprehend, a song as good as ‘Thank you girl’ being hidden on the B-side of an early Beatles single.

Not long before the Beatles toured New Zealand, they released what many critics consider to be their first genuine double A-side hit, ‘Can’t buy me love’ coupled with ‘You can’t do that’. Again it seemed daft that any band would hide a rock song as good as ‘You can’t do that’ on the B-side. Their earlier singles all had interesting material on the flip-sides. ‘Love me do’, in its first configuration, had Paul McCartney’s pure pop ballad ‘PS I love you’ on the other side. New Zealand female fans really loved it, as much for the fine sentiments as for the words and music. ‘Please please me’ had another Lennon-McCartney song on the flip-side, ‘Ask me why’, which seemed to confirm that the Beatles were committed to putting their own stuff on both sides of their singles. That was a landmark in rock music. The accepted thing in the parasitic rock industry was for the manager of any given star or stars to help pen a truly awful throwaway and stick that on the flipside, in the interests of inveigling easy royalties. B (for bad) sides really were B-sides.

But the Beatles were different – and the trend continued. ‘From me to you’ had ‘Thank you girl’ on the B-side. Some Beatle music worshippers claimed that to be the first double-sided single because ‘Thank you girl’ was so unabashedly catchy. It really was a ‘happy’ song, with John and Paul propelling the line, ‘you make me glad when I was blue’ into the consciousness on the wings of an unusual chord change that coincided with the word ‘glad’. ‘She loves you’ was so good that anything on the flipside could not possibly compete. And it couldn’t. ‘I’ll get you’ was catchy, but definitely the B-side. The same applied to ‘I want to hold your hand’. That song was a double A, A-plus track in its own right. In fact ‘This boy’, a John Lennon ballad on the B-side, was just about the least liked song from their early catalogue for many fans. It was considered to be too slow at a time when all Beatles songs – both sides – were expected to be upbeat. Years later fans began listening more intently to ‘This boy’ and were staggered at the complexity of the three-part harmony. It may not have been a great song but the singing was pure, Liverpudlian, nasal indulgence. The precise mechanics of the harmonies remain impenetrable to many.

While everyone went nuts over the music, it was interesting how some Beatle music followers, with the benefit of hindsight, came up with the notion that we were looking at the Beatles through rose-tinted glasses. The first album, Please Please Me, was great, if for no other reason than that in ‘I saw her standing there’, the album contained a track that stacked up with the best singles of the early years. Yet ‘I saw her standing there’ wasn’t even a single, not at the outset anyway. Cliff Richard or Bobby Vee would have killed for a rock-pop song like that.

And from the outset there were some unexpected preferences. A number of fans claimed they were turned on to the album by John singing ‘Anna’, which was not a Lennon-McCartney original. It was a good cover version but, it seemed, right-thinking Beatle nuts did not go ape over ‘Anna’. Perhaps those who did, the guys anyway, had a crush on a bird called ‘Anna’. There was obviously a fair bit of subjectivity involved with Beatle music. After all, their fans were essentially teenagers and young adults who had various agendas and esoteric notions of identity and where they fitted into this earth-moving stuff.

With the Beatles, the second album, was regarded by most as a masterpiece, a creative progression on Please Please Me. It was also regarded as a laudable display of democracy in action within the band. George Harrison was allocated four lead vocal spotlights, including his own composition, ‘Don’t bother me’. Paul sang another four and John, the dominant voice in all ways at this stage of Beatle evolution, sang seven. Ringo was not left out and got to sing ‘I wanna be your man’, which became a hit for the Beatles’ apparent arch-rivals, the Rolling Stones. Talk about nice guys! The Beatles were not only sharing their own spoils, they were being generously inclusive of the wider rock world.

Yet there were those who tended to be dismissive. For a start, With the Beatles was a silly name for an album, these doubting Thomases claimed. The best tracks, apparently, were good old rock ’n’ rollers like ‘Roll over Beethoven’ and ‘Money’. ‘All my loving’, Paul’s song, made it from the outset as a single in the States, but nothing else seemed powerful enough to be culled as a 45. ‘Hold me tight’, also by Paul, was cited as being one of the weakest Beatle songs. Why, Paul even rewrote the song, using the same title, and came up with something more progressive for one of his later ‘Wings’ releases. ‘It won’t be long’ and ‘Don’t bother me’ were regarded as ‘promising’, and some musical expert in Britain spoke of aeolian cadences in ‘Not a second time’. But hey, cover versions like ‘You really got a hold on me’ and ‘Devil in her heart’ were just fillers. And ‘Till there was you’ was one of the most irritating tracks: Paul’s chance to wallow in the balladeer’s role. He was beginning to come across as a poseur to some, and the rest of us didn’t want to acknowledge the fact, or spoil the Beatles’ party.

But already the Beatles were several steps ahead of the pack. Quantity and quality issues surfaced. John and Paul had so many good songs they now deemed it undesirable to have to pluck singles from albums, which they rapidly came to regard as hermetically sealed, organic statements in themselves. To preserve the integrity of With the Beatles as an album, they came up with ‘I want to hold your hand’ as a single! Someone suggested that was the only reason they went away to write one of the greatest singles in rock history. If that was so, the talents of Lennon-McCartney were becoming downright scary.

There had never been any doubt about the Beatles’ ability to compose, sing and play in an original way. Even the two-part harmony on ‘Love me do’ was unusual. John and Paul sang two clearly demarcated, yet dovetailing four-note verse lines that rather denied the well-documented ‘simplicity’ of the song. ‘Seemingly simple’ was a better phrase for much Beatle music. The man and woman in the street heard it as ‘simple’, yet there were often complex dynamics that anchored the song to the subconscious.

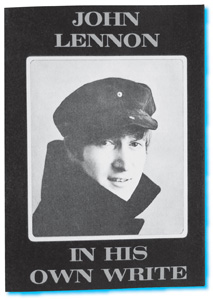

The lyrics of Beatles songs were beginning to reflect the evolutionary process as well. While there was never any doubting the quality and quantity of the tunes and harmonies, the words – and wordplay – developed dramatically. In John Lennon, the band had some sort of linguistic genius lurking in their ranks. Anyone who reads his books, In His Own Write (1964) and A Spaniard in the Works (1965), will come away with a different perspective on the English language. Others found his wordplay and bizarre juxtapositions slightly disorientating, but surrendered to the fact that Lennon, as a wordsmith, had an originality not usually associated with rock musicians.

The early Beatles lyrics concentrated on ‘this boy, that girl, love me do, she loves you’, seemingly traditional combinations expressing youthful emotions. Plenty of young love sentiments in the song mix helped capture the hearts of western females. The boys, most of them, just accepted that this was the way song words were. And yet the Lennon wordplay had already made its mark. The very name, the Beatles, which had been John’s invention, and the title of their first big hit ‘Please please me’, another Lennon throwaway, were extremely clever by the standards of the day.

The mood of the early Beatle lyrics was uplifting and celebratory, yet even on their first album, songs like ‘Misery’ and ‘There’s a place’ were atmospheric and isolating, at odds with the dominant, upbeat image of their pioneering work. John Lennon played the major lyrical hand in both those early songs, and from the outset displayed an emotional range and depth that caught Beatle fans napping. At Beatle parties, happy fans jumped around and celebrated to the morbid sentiments of ‘Misery’ as if it was just another joyous Beatle anthem.

On With the Beatles, George Harrison’s first composition, ‘Don’t bother me’, was a love song of sorts, although it possessed a caustic edge. The loner in George slipped out. He already sounded cynical and isolated by Beatlemania. John was now sending out assertive signals too, via the lyrics of ‘Not a second time’. He was sick, lyrically, of being pushed around. By the time ‘I call your name’, off the ‘Long tall Sally’ EP, came along, John sounded in pain. Love in song was turning sour. Typically, at this stage of his development, Paul’s major lyrical contributions on With the Beatles, ‘All my loving’ and ‘Hold me tight’, were still pure, positive love songs.

Then, with the single ‘Can’t buy me love’, Paul, while still singing about love, was touching on the folly of money as well. It was an almost direct lyrical response to the bald, greedy sentiments expressed in ‘Money’ off With the Beatles (‘Give me money, that’s what I want’). John’s ‘You can’t do that’ on the flip-side of ‘Can’t buy me love’ was the first of his ‘jealous’ love songs. Although still writing about love, the Beatles were now producing lyrics with more complexity. When they harmonised ‘everybody’s green’ on ‘You can’t do that’, a lot of fans did a doubletake. Was John now talking about the downside of a booze hangover? Had the Beatles been stuck in the groove, and not evolving lyrically, the line might have gone, ‘everybody’s jealous, ’cause I’m the one who won your love.’

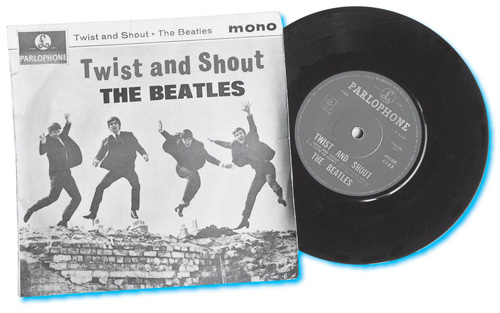

If there was one thing about Beatle music, it brought all sorts of aficionados and critics out of the woodwork. I knew a guy called Bob who hated the Beatles’ hair and accent and their original compositions. As an unabashed Elvis fan and part-time bikie, Bob figured the best music could only come out of America. He tried to justify the point by naming all the nonoriginal songs the Beatles had already released: ‘Anna’ written by Arthur Alexander, ‘Chains’ by Goffin and King, ‘Boys’ (Dixon-Farrell), ‘Baby it’s you’ (David-Williams-Bacharach), ‘A taste of honey’ (Marlow-Scott), ‘Twist and shout’ (Medley-Russell), ‘Till there was you’ (Willson), ‘Please Mister Postman’ (Holland), ‘Roll over Beethoven’ (Chuck Berry), ‘You really got a hold on me’ (Smokey Robinson), ‘Devil in her heart’ (Drapkin), ‘Money’ (Bradford-Gordy), ‘Matchbox’ (Carl Perkins), ‘Bad boy’ and ‘Slow down’ (both Larry Williams), and ‘Long tall Sally’ (Johnson-Penniman-Blackwell).

That was sixteen tracks, more than an entire album’s worth of cover versions, Bob reckoned. When the Beatles for Sale and Help! albums came along, the number of covers had climbed to 24, enough for a double album. Significantly, by the time of Help! the number of covers had been limited to two. The other tracks were all original Beatle material. And of course, earlier A Hard Day’s Night had been all Lennon-McCartney.

Bob, the original Elvis fan, who championed the non-original Beatle tracks, reckoned he had no time for ‘Please, please me’, ‘She loves you’ and all the other originals that helped change the world. Such a reactionary stance led to virtual stand-up fights over which of the Beatle songs were more valid. We acknowledged that the Beatles had, through their versions of some reasonably obscure American songs (only ‘Long tall Sally’, a big hit for Little Richard, ‘Boys’ and ‘Baby it’s you’, hits for the girl-group the Shirelles, and ‘Twist and shout’ by the Isley Brothers were known to us) opened our ears to some strong American tracks. However, we were not prepared to put up with Bob’s debunking of the beloved Beatle originals. Some of the exchanges at parties were very willing. Bob was a bit older than us, but you had to question even his evaluation of Elvis records. He bought all those god-awful Elvis movie soundtrack albums. He reckoned GI Blues was as good as early Elvis.

Finally the Beatles themselves got the better of Bob. God knows our powers of persuasion didn’t have an effect on him. In 1964, not long after the Beatles had left New Zealand, Bob was cock-a-hoop over a new Beatle release that proved, he reckoned, that the Beatles still had to cling on to American covers for credibility. On the flip side of ‘I feel fine’, which Bob found ‘trivial’ simply, we figured, because it was a Lennon original, was ‘She’s a woman’, a Paul McCartney rocker. Bob was adamant that ‘She’s a woman’ was an old Little Richard track. Even when we showed him the ‘Lennon-McCartney’ credit on the record label, he appealed on the grounds that there’d been some sort of fabrication, plagiarism or mere misprint. He was now prepared to wager that the Beatles were committing commercial fraud, claiming a song that wasn’t theirs. The mood turned ugly again, but we figured that dousing Bob with Waitemata draught would be a waste of good beer. We just got on with the business of marvelling at the incredible guitar syncopation and George’s murderous lead break – and Paul’s great rock singing. ‘She’s a woman’ did sound a bit like Little Richard, we conceded, and Bob lightened up a bit. And of course he loved the track. He played it all the time. No one minded at all.

Bob probably still reckons ‘She’s a woman’ is a Little Richard tune. I wonder how he would have felt when he heard Fats Domino, another of his favourites, doing a version of Paul’s ‘Lady Madonna’ a few years later. He was a complex sort of Beatle reactionary. We reckon he might have been involved in one of the egg-throwing episodes that occurred in the South Island when the Beatles got splattered. Another factor that might have been weighing heavily upon him at the time of the Beatle invasion was the fact that he had been going prematurely bald. Even Elvis didn’t go bald, although he went everything else. Premature baldness was a cruel fate to have to contemplate at a time when hair and lots of it became de rigueur.

Some young New Zealand music lovers flirted with the idea of boarding the Beatle bandwagon, but found it more appropriate to express their individuality by opting for other bands. Sensing that the Beatles were becoming acceptable to the establishment, these fans sided with combos like the Rolling Stones and the Kinks, knowing full well that their parents and other ‘guardians of decency’ would blanch at allegiance with such outriders.

On this side of the spectrum, well short of the Beatle bandwagon in fact, there were those who aligned themselves with Merseyside and other British bands who, but for the Beatles, would never have made it out of Liverpool or London. Trevor was one such believer. He worshipped the Searchers and the Dave Clark Five. We had him on about the Dave Clark Five. We suggested that the Don Clarke Five out of Morrinsville were better singers (there were five Clarke brothers who all played rugby for Kereone – and once for Waikato). By way of retort, Trevor then announced that a new group we may not have heard about, Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas, were in fact better than the Beatles. We waded in at this point. Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas had cracked the charts using, almost exclusively in the early days, Lennon-McCartney giveaways. ‘Bad to me’, ‘From a window’, ‘I call your name’ and a couple of others were all Lennon-McCartney songs. Was Trevor really suggesting that Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas were better than the Beatles, even if the Beatles had written most of their hits? He was, and did.

There was no doubting that Beatle music, while having a happy component, also possessed a hidden power. Perhaps it was too momentous and ground-breaking for some. However, after their ’64 tour and the dust had time to settle, they released A Hard Day’s Night, the movie and the album. To most Beatle music fans it was another quantum leap. To those who had reserved judgement it was confirmation of their greatness. For those who thought the bubble was about to burst, there was now evidence to the contrary.

For a start, and it was a real first, all thirteen tracks of A Hard Day’s Night were written by Lennon-McCartney, and there was barely a bum track. George Harrison didn’t get a writer’s look-in, although he ‘had a sing’, as he put it, through the medium of ‘I’m happy just to dance with you’, which was written mainly by John. Ringo didn’t get to sing at all, and although there had been talk, during the 1964 New Zealand tour, of Ringo having penned a song called ‘Don’t pass me by’ (which surfaced four years later on the double album The Beatles, aka the White Album), they did pass him by.

A Hard Day’s Night showcased John Lennon’s brilliance as a songwriter. He wrote most of the songs, and yet two of Paul’s ballads (no more ‘A taste of honey’ and ‘Till there was you’) would go on to become standards in their own right. ‘And I love her’ was nominated by the Beatles themselves as the best song on the album. They all said as much during a press conference while on tour in New Zealand. ‘Things we said today’, the other stand-out McCartney composition, was often regarded as being light years ahead of ‘And I love her’. The use of descending chords, where normally you’d expect otherwise, made the song a real original. Just when you figured you’d cleared the bluesy, melancholy bits and were about to hit a happy chorus, McCartney would not break out of the bittersweet straitjacket that made the song so distinctive.

It was an extremely nostalgic song, a powerful statement coming from a bunch of young blokes who had the world at their feet. Or from Paul, on his own. At that point you sensed that this was very much Paul’s song, just as ‘I should have known better’, with its jolly vocalisations and ‘happy’ chords, was distinctly John. Even back then the two songwriters were becoming distinctive voices – and chord sets. John’s dominance on A Hard Day’s Night was now producing a critical dynamic of the band’s progression and longevity. Paul, something of a sleeping partner, had been goaded into action. To hell with what the fans craved; it was now the internal battle, the one-upmanship between John and Paul that would propel the Beatles above and beyond the call of duty.

It wasn’t until a few years after the Beatles explosion that I studied the Beatles’ songs on the guitar, which I had begun learning at 13. I then appreciated the use of interesting and less common chords in many of their songs. In my early twenties, I became a full time guitar teacher, and began playing electric guitar in rock bands in Nelson. I found the Beatles songs to be an excellent resource for teaching, although by then my students were more excited by the latest recordings of the likes of Jethro Tull and our own John Hanlon.

Looking back now, as a full-time concert guitarist with my own groups, and writing my own songs and instrumentals, I would say that the Beatles have had some influence on my own composing. I have sometimes made use of the high plucked lead guitar arpeggios used in the song ‘And I love her’. I am also inspired by some of the social realism in the lyrics of John Lennon. There was something magical about the early lives of those high-spirited lads from Liverpool, who lived the kind of life most of us only dreamed about.

JONATHON HARPER, CONCERT GUITARIST, WELLINGTON

The Beatles were coming! They would be doing concerts in the four main centres. To coincide with the event of a lifetime Parlophone released an EP on 19 June, a few days before the tour, called ‘Long tall Sally’. I remember getting my copy and spiriting it home with all due care and attention. It was like carrying a precious Egyptian vase. I can’t remember what the cover was like. I was more concerned with getting the record on the turntable. It seems a strange artefact now. Four songs by the Beatles, only one of which was an original Lennon-McCartney, and even that one – ‘I call your name’ – had been used before. It was the back-side of ‘Bad to me’ by Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas.

But that didn’t stop my mates and me organising a party based specifically on the arrival of a new Beatle recording. How many EPs had that sort of pulling power? Grady Martin, Victor Sylvester?

There were about 200 Beatle nuts at the party, that pulsated to the sounds of ‘Matchbox’, a Carl Perkins song sung by Ringo, ‘Long tall Sally’, Little Richard’s classic sung by Paul, ‘Slow down’, a rare Larry Williams track sung by John, and ‘I call your name’, which for some idealistic reason I figured was sung – very well, it had to be admitted – by George.

We all fancied ourselves as singers of Beatle songs, but when Paul sang ‘Long tall Sally’ in a robust falsetto, there was no way we could get that high. Not then anyway. Ringo sounded typically rollicking in ‘Matchbox’ and John was just John in the dense, menacing ‘Slow down’. No one had that edge like John. ‘I call your name’ was the big surprise though. It made Billy J’s version sound limp. It always was a great song anyway. Mama Cass did a wonderfully smooth version. But it was amazing the way the Beatles took ownership of the song. It was so powerful and metallic and the beat shook the brickwork. George’s guitar work transformed the song.

Teenagers playing Beatles records in the 1960s.

Later, on tour, John came forward to sing ‘I call your name’. For some reason I had seen the ‘Long tall Sally’ EP as a democratic artefact. Every band member had solo vocal spotlights. I really did think that George sang ‘I call your name’. John had already had his turn with ‘Slow down’. But there it was. John sang ‘I call your name’. As John’s voice boomed out – it was one of the few songs you could hear the bones of – you realised that George would have been too busy concentrating on and playing those brilliant electric-edged guitar licks to do the singing as well. To me it was George’s song anyway. I defy anyone, even to this day, to find me a better piece of electric guitar work.

A lot of people got wasted at our party. I remember one guy in a Beatle wig going out a window and breaking an arm. Another guy had his little finger run over by a backing car and he was pinned in this manner for some time. Amputation was considered an option because someone had lost the car keys. A rugby team gatecrashed the party and one or two of the more brain-dead forwards roughed up the longer-haired Beatle fans. But in the end the guest of honour, ‘Long tall Sally’, won everyone over.

RUSSELL YOUNG, ACCOUNTANT, TE KUITI