By 1964, the Beatles had already spread their tentacles into the western world and beyond. Before undertaking their trip downunder, they embarked on a whistlestop barnstorming of the USA. ‘I want to hold your hand’ had reached Number 1 on the American charts – a milestone for a British act. Images of the Beatles captivating Americans on the Ed Sullivan Show and in press conferences flashed on to New Zealand television screens.

From the USA the Beatles returned to England to make the movie A Hard Day’s Night before heading out again on a concert tour that would include Hong Kong, Australia and New Zealand. Ringo nearly put the kibosh on the tour. During a photo session, he collapsed and was rushed to hospital with tonsillitis. The Beatles were sorely tempted to cancel the tour, given that the band was already a four-headed hydra. Take away one head ... But commitments are commitments. Jimmy Nicol, a British drummer from Georgie Fame’s band who, at a pinch, could be made to look like a Beatle, was drafted in to deputise for Ringo. And so the Beatles show went on.

On 11 June the band touched down in Australia. They performed in Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney (they also appeared in Brisbane on their way back from New Zealand). Jimmy Nicol deputised in four shows, before Ringo, triumphant if a little wan, rejoined his mates in Melbourne. New Zealand fans were delighted that Ringo was back in the saddle. Excitement mounted as everyone began to wonder about the phenomenon that was about to wing our way. After all, 300,000 Australians had gathered to welcome the Beatles outside their Adelaide hotel. It was the largest such gathering ever recorded in Australia.

On 21 June 1964, 7000 Beatle fans began screaming as the TEAL Electra carrying the Beatles touched down at Wellington Airport. Casual onlookers and listeners reckoned the screaming obliterated the sound a turbo-prop airliner makes as it taxis down the runway. As the four Beatles emerged from the plane the screaming—not unlike the sound of a modern wide-bodied jet—intensified.

The Beatles had finally touched down on New Zealand soil. Members of Te Pataka concert party presented an early Maori perspective to the welcome, as tiki and poi were presented to the hirsute visitors. Reporters and cameramen swirled. Members of the concert party applied the hongi to each of the Beatle noses. Ringo, he of the generous appendage, responded willingly to the ancient Maori custom. A large replica of a kiwi was presented to the Beatles. The fact that the gift had been made by the Auckland Returned Servicemen’s Association struck an immediate, poignant note. The RSA, one of the more conservative bastions, would never have fashioned such an adornment had Elvis Presley been touching down.

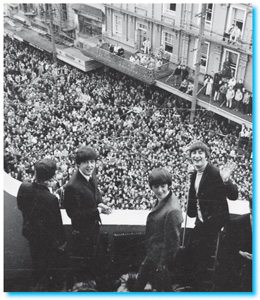

The Beatles were transported on the tray of a small truck, past the screaming hordes, until they reached a waiting sedan among a collection of vehicles, constituting a cavalcade that swept the visitors to their Wellington hotel. Three thousand fans lined the route and gathered around the Hotel St George. The bedlam of screaming, shouting, twisting, surging fans could be heard echoing around the canyons of central Wellington.

While the surging crowds were generally well behaved, there were one or two ‘casualties’. At the airport one young girl was taken to hospital by ambulance after cutting her leg while trying to climb a wire-mesh fence. In the heart of Wellington itself two police motorbikes were pushed over, and another, with rider, came to grief in the mêlée, although the policeman soon regained his composure.

Police were already applying various plan Bs to ensure the safety of the Beatles. They spirited the group through the bottle-store entrance of the St George, while the crowd focused their attention on the main entrance. Very soon the Beatles appeared on the hotel balcony and the crowd let out a deafening roar. Paul McCartney, tongue in cheek, invited members of the crowd to join them. Two young men, however, had serious intentions and before policemen could intervene, they had clambered up the fire escape towards the balcony. Both were apprehended at the balcony, but not before one of them had shaken Paul McCartney’s hand (I want to hold your hand).

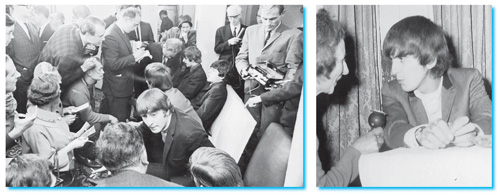

At the first press conference at the hotel John Lennon was asked for his opinion about the Hotel St George. He replied that St George himself must have opened it, given its elderly status.

‘George (Harrison) has settled in very quickly at the St George,’ added Lennon. The Beatles had obviously brought their famous wit with them.

The press conference revealed that all four Beatles liked New Zealand mutton and butter and George liked bacon and eggs. The conference also portrayed the Beatles as four likeable young men who, while being quick-witted and good-humoured, were also able to respond to serious questions in a manner not usually associated with rock stars.

On the other side of the divide, the police announced that Wellington teenagers were a credit to teenagers everywhere, in the way they had been able to restrain themselves. From a public relations perspective the Beatles tour had made an auspicious beginning.

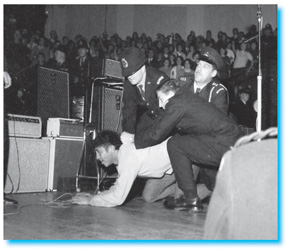

The Beatles were scheduled to do two concerts at the Wellington Town Hall on consecutive evenings. The first concert – the 6p.m. show – was straightforward enough by Beatle concert standards. Several girls were cautioned for leaning too far over the balcony rail and a young Maori boy evaded the security cordon and somehow leapt ten feet from the front row seats on to the stage. The police moved in and the boy quickly retreated.

The second show at 8.30p.m. brought to the surface more sinister undertones. Hundreds of hysterical teenagers surged from their seats towards the stage and the full contingent of police and security guards was obliged to quell a near-riot. The security line was breached and Paul and Ringo were manhandled, although they showed their true trooper colours by smiling and continuing to play. John and George did the same. At the end of the concert everyone was on their feet and the National Anthem was played in an attempt to control the masses. Such a gesture seemed quaint, even at the time, and it appears more likely that the request for calm by Paul McCartney towards the end averted a more serious disturbance.

The police effort was galvanised by events at the second Wellington concert. They and the rest of New Zealand now knew that the mere appearance of the Beatles, in concert and elsewhere, would unleash forces that hadn’t been encountered before. Some commentators had suggested before the tour that New Zealand teenagers and young adults would react in a more stoic, controlled, Kiwi fashion. None of the bedlam like that witnessed overseas. They were quite wrong. The Beatles were a global phenomenon. Even conservative New Zealand was not immune.

Counter-forces were at work too. A group of anti-Beatle fly-by-nighters were apprehended trying to break into the Beatles’ hotel, with the avowed intention of cutting the Beatles’ hair. A Beatle protection police force had been set up, and they treated very seriously the bomb threats that arrived by way of anonymous phone calls. Bomb attacks would be made on the Hotel St George and the Wellington Town Hall. Thankfully such threats amounted to hoaxes, but the message was clear: not everyone was ecstatic about the Beatle phenomenon.

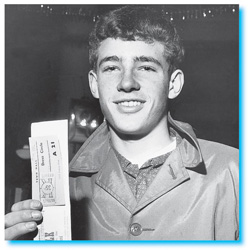

I was the first in the queue to get tickets to the Wellington concert, which, because the Beatles played Wellington first, in effect made me the first New Zealander to procure a Beatle concert ticket. I was surprised at the lack of competition for places in the queue. I expected something like the queuing that went on outside Athletic Park for a rugby test match. I had experience of that phenomenon too, being a keen rugby player and a big All Black fan. In particular I recall the huge, milling throngs that gathered throughout the night, before the second test between the All Blacks and Springboks in 1956.

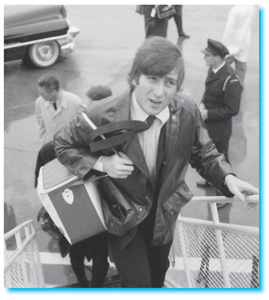

I took up station for the Beatle tickets queue at 7a.m., but for the early part of proceedings was on my own. Later on, as day broke, about 300 fans had joined me, and when I finally came away with my precious Beatle concert ticket I was snapped by a press photographer and ended up on the front page of the Evening Post with my Beatle ticket prominently displayed.

Because I was the first to buy a ticket, I had the luxury of choosing where I would sit in the Wellington Town Hall. John Lennon was the Beatle who fascinated me the most, so I was able to secure a seat directly opposite where I knew he would be standing. The concert started, appropriately, with John’s song ‘You can’t do that’, and despite what a lot of people said about the screaming and other disruptive noises, I was able to hear a lot of the music. It probably had a lot to do with the fact that I was right up the front.

On stage John anchored the ship with his legs apart in a solid, basically unmoving stance. Ringo nailed the sound down at the back with surprising power for such a little chap. Just out of hospital too. Paul performed the function of MC, the charmer of the birds. George, in the middle, looking very much the youngest, concentrated hard on his guitar work.

To me John was definitely the most influential Beatle. Not only was he the obvious leader of the band at the concert (he threatened to take the Beatles off because the local sound system was so primitive), but to me he was more than a musician – he was an artist. When he put out his first book In His Own Write, complete with his own witty wordplay and line drawings, it was obvious that being a Beatle was only part of his range of creative skills. In 1964 he wrote and sang much of the Beatle music. He played harmonica and found fantastic chords. He occasionally wore a leather hat. Already, within a band that was undeniably original, he was pushing the boundaries.

Although I was able to hear a lot of the music amid the turmoil of the Town Hall, it was noticeable that on occasions John had to turn to Ringo, sitting in splendid isolation at his drums at the rear of the stage, to make sure that Ringo was able to keep in time with the others.

Even back then I considered Paul to be more an entertainer than an artist. He was more representative of Tin Pan Alley than John, and while such a stance was invaluable to the overall Beatle songs and sound, it was John who struck me as being the creative original in the band.

GRAEME COLLINS, MUSICIAN, WELLINGTON

Before the Beatles arrived in New Zealand Neville Chamberlain, or ‘Cham the man’ as he was known, held a contest via his nationwide pop show. You had to make as many words as possible out of the two words, ‘The Beatles’, and the prize was to be ‘A trip to meet the Beatles’, including tickets to their evening show in Wellington. There were to be four winners.

At home in Timaru, I made a couple of lists. It was now the May holidays. I worked with a dictionary and added ‘s’ to the ends of words where possible. I ended up with 1197 words. The lists were mailed off.

One night in early June 1964 there was a phone call from Wellington. Great excitement! I was out on a training run with friends, but took the call the following night. I was one of the winners. My air tickets would be mailed shortly. The winners were announced by Cham on his show. Word spread around Timaru. My sister Stephanie arrived home with a handful of senior boarder autograph books from school. They were sent back. The only autographs I got from the Beatles were for my brother and sister.

As I had to have two days off school, a meeting was arranged with my headmaster. I’m not sure that I asked, but rather advised that I would be away. Fred Crombie seemed unusually content. Perhaps he was a secret fan, along with my geography master who used to advise the class that ‘money can’t buy me study...’

It was an early flight from Levels Airport and coolish in the DC6, so passengers were given blankets. My first big flight. The Canterbury Plains were patchwork, the Kaikouras majestic, dusted in snow.

Cham and his 2IC, Nick, met me at Wellington Airport and I soon met the other winners: Linda and Noeline from Auckland and Wellington, and a guy from St Andrews in Christchurch.

We were all staying at the Travel Lodge by the airport. It was close to midday, so we were all taken into Willis Street for lunch, just by the Hotel St George where the Beatles were staying. There were some girls on each of the four corners, but not many. After a tour of the city we went to EMI Studios to look at their operation. As we left, they presented the four of us with a copy of the new Beatles EP, which included ‘Long tall Sally’. It was later autographed, along with the two LPs that were part of the contest prize.

We had an early dinner at the ‘Mermaid’ back at the Lodge. I had put my new jacket on and my brother Tony’s newish black leather shoes, before heading into the Town Hall where the meeting with the Beatles was to take place after the 6p.m. show. The seven, comprising Cham, his boss, Nick the 2IC and the four of us wandered down the side of the hall to a door next to the stage. We were ushered into a small room. The Beatles were sitting around a dining table in white shirt-sleeves. There was fruit and Coke. Perhaps this was the first course. A slim guard stood inside the door while a lady came in with a watermelon on a tray. It was made up to look like a beetle. We chatted and the Beatles autographed. Their accents were broad. Cham was taping madly while the Beatles remained relaxed and friendly. They joked among themselves as a photographer was shooting. We were given copies of photos which are still treasured.

Our seats at the concert were ten rows from the front. Cham taped the show. A Victoria University professor in the audience was making a study of the performance. He reckoned all the young people would be deaf within a couple of years. A band called the Phantoms started the gig. They had a good sound and a great drummer. The Beatles appeared in their Beatle suits. There was some female screaming, then and throughout the show, but only for short periods. One or two girls walked to the stage, but the majority remained seated throughout. I don’t recall any interaction with the audience. The Beatles’ songs were very well played, but of course, the fans would have turned up just to see them. Ringo sang ‘Boys’; ‘Twist and shout’ was sung last.

So who was this band? Would they last longer than the Dave Clark Five or Gerry and the Pacemakers? I caught the end of the late news that night. TVNZ’s Bill Toft referred to the drummer as Ring O.

CHRIS WATSON, GREENLANE, AUCKLAND

I went to one of the Beatles’ concerts in Wellington with a mate of mine, Dave Henderson, who later went on to play a hundred games as a half-back for the Wellington rugby team. We sat in the organ loft of the Wellington Town Hall, about two or three rows back from the stage, looking out over the top of Ringo Starr and his drum kit. Despite the fact that the Beatles basically had their backs to us, it was most noticeable – and certainly appreciated – the way all four of them turned around from time to time to make us feel part of the action.

Ringo had just joined the Australasian tour after a bout of tonsillitis. Jimmy Nicol, the stand-in drummer, returned to England after the Melbourne concerts, and we felt privileged to be able to see the band back to full strength. It wouldn’t have seemed the same without Ringo.

When the concert began the noise was unbelievable. Girls screamed, but there was a cacophony of cheering from the boys and young men as well. The noise generated by the Beatles themselves was monstrous. I’d never heard anything to compare with it back then.

By my reckoning the Beatles were on stage for only 22 minutes but we felt we’d received our money’s worth. I’ve never seen or heard anything quite like it in terms of excitement and history in the making.

It was the first time I’d seen security guards anywhere in New Zealand, and at the end of the show we walked down several flights of stairs towards the stage. We found ourselves hovering around Ringo’s now-abandoned drum kit and noticed a hand-written list of the songs the Beatles performed, taped to the bass drum. We figured it would be dead easy to reach over and claim the list as a souvenir. In the light of the value of Beatle memorabilia in this day and age, God knows what that list would be worth now, but a hulking security guard – I think he had been flown in like the others from Australia – advised us to ‘clear off’, or words to that effect.

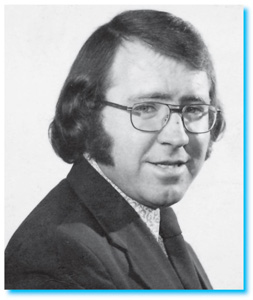

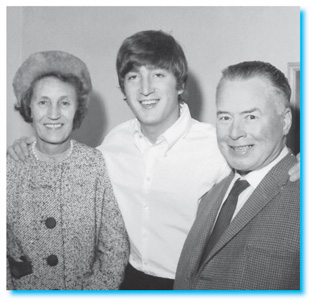

Keith Quinn a few years after the Beatles’ visit.

After the concert we joined the excited, jostling crowd that gathered outside the Hotel St George where the Beatles were staying. At about 10.30p.m. the Beatles appeared from their hotel rooms, waved to the screaming masses, then retreated. I remember the curtains being pulled shut, which effectively ended the evening’s entertainment. It was significant that the Beatles show – in its entirety – did not conclude for most of us until that moment. It was only when I crashed into bed that night that I realised my ears were ringing.

KEITH QUINN, SPORTS BROADCASTER/WRITER, WELLINGTON

Lynda Mathews, John Lennon’s second cousin, who was then a 17year-old nurse at a private hospital in Masterton, recalls the Beatles’ visit:

The Beatles’ tour was an exciting time for my family, particularly my father, who had stayed in touch with John’s Aunt Mimi.

My grandmother, Harriet Millward, and John’s grandmother, Annie, were sisters. My father, Jim Mathews, was born in Liverpool and came out to New Zealand when he was a baby. My father and John’s Aunt Mimi corresponded with each other for many years and became very close. At the outset we knew that John was in a band, but we didn’t know much about them.

Several days before the Beatles actually touched down in New Zealand, Aunt Mimi arrived by plane in Wellington. My parents and other relatives met her off the plane and drove her up to Masterton, where they stopped for tea at a family friend’s home. It was there that I first met her, before we all travelled back to our farm at Pleckville, near Eketahuna. Mimi remained in New Zealand for several months, long after the Beatles had departed.

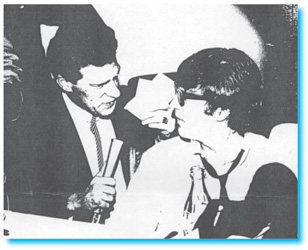

I was lucky enough to see two Beatle concerts in Wellington. I saw the first evening show and, after John had given me free tickets, part of the following afternoon’s session. Because I was John’s second cousin, the local newspaper was able to arrange a meeting with John and the other Beatles while they were in Wellington. Not surprisingly, many other fans had made the same claim – that they were related to the Beatles – but Derek Taylor, the Beatles’ publicity officer, identified the family likeness when he met me. As a consequence, I was able to meet John and the others face to face. I remember sitting on a bed in the Beatles’ hotel room, sipping whisky and coke, the Beatles’ favourite tipple at that time. Meanwhile, three Wellington high school girls managed to clamber up a drainpipe in an attempt to meet their idols. While they had to be content with autographs in the corridor, I felt very privileged to have made it into the inner sanctum. It was a funny feeling knowing that because I was related to John, I was doing what thousands of young Kiwi girls would have given an arm and a leg to be able to do.

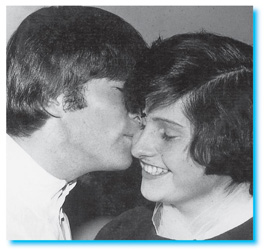

John Lennon makes the acquaintance of his second cousin, Lynda Mathews, at the Hotel St George, Wellington.

While I was talking to John, the other Beatles walked in. Paul McCartney was amazed at the family resemblance. When it was time to go, John asked me to take care of Aunt Mimi. You could sense the strong bond and love that John felt for Mimi, the woman who raised him. In fact, one of the main reasons the Beatles visited New Zealand was because John knew that his aunt had several relatives out here, and he wanted to give something back to her.

After Mimi returned to England she and my father continued to write to each other until Dad died in 1980. My family still keep in touch with the Liverpool connection through John’s cousin, Stanley Parkes. The Beatle legacy has been taken up by the next generation too. In 1987, my daughter Amanda wrote John’s life story for a Queen’s Award, the ultimate award in Girls Brigade.

LYNDA MATHEWS, SECOND COUSIN OF JOHN LENNON

Hotel security was breached completely when four girls from Chilton St James School in Lower Hutt managed to walk past guards and confront Ringo on the sixth floor. Ringo handled the situation diplomatically and after autographing the girls’ arms, persuaded them to leave. When the four girls returned to school they were ordered to wash the signatures off their arms, and had to write letters of apology to the school board.

While in Wellington the Beatles met up with some of their New Zealand-based relatives. Christine, Patricia and Teresa Starkey chewed the fat with Ringo (though their precise relationship to him is unclear). John Lennon’s Aunt Mimi was visiting New Zealand at the time, and she spent some time staying with her cousin, Jim Mathews of Eketahuna. Later she caught up with rellies in Hamilton.

Back at the Hotel St George, another young woman was able to breach security and found herself by mistake in the room where the Beatles’ support act, Sounds Incorporated, were staying. On being told she was not permitted to see the Beatles, she slashed her wrists. After a quick dash to hospital she was patched up and discharged. It had been an inside job. She had booked into the hotel with the unabashed intention of meeting the Beatles. ‘Girl tries to die for the Beatles’ announced the press headlines the next morning. As ‘shock horror’ headlines go, it was very radical for the times, and New Zealanders in general were becoming somewhat alarmed.

The police too. After they had performed their Wellington concerts, the operation to whisk the Beatles away from their hotel to the airport was carried out with sophisticated precision. As the Beatles’ Viscount airliner took off for Auckland, with the Beatles intact and on board, the rest of New Zealand braced themselves for the onslaught.