A couple of hours before dusk, I pulled into Zoar in northeast Ohio. Dense fog covered the trees and cupolas like bed sheets. At first, I thought I was driving into heavy smoke, but then I realized that the light rain and high humidity had created a wall of haze that stood along the Ohio and Erie Canal. On the town’s narrow streets, yellow lights glowed dimly, invitingly, from back porches and gardens buried deep within the fog.

I came to stay the night in one of Ohio’s historic communities: a German Separatist village that flourished in the early 1800s. I wanted to experience Zoar for what it was—a communal enclave in Buckeye farm country. I wasn’t disappointed in the surroundings, for they reminded me of a set for one of those horror films about an old village coping with its demons. The place looked downright eerie in the thick fog. As I drove past log houses and the big, unused hotel, I felt a little uneasy, and then I remembered that this town also sponsors such benign events as a Christmas walk and a Civil War camp reenactment.

The old canal still has water in it—as well as too many big mosquitoes that attacked me through my open car window. As I carried my suitcase into the Cowger House Bed and Breakfast (known in Zoar as the Number Nine House), I paused to read a large, framed rectangular poster from the 1890s that was affixed to a wall in the dark rear hall:

PUBLIC SALE.

The trustees of Separatists of Zoar will sell at public sale … 100 houses! 100 milk cows! 200 young cattle! 300 sheep! 100 hogs!

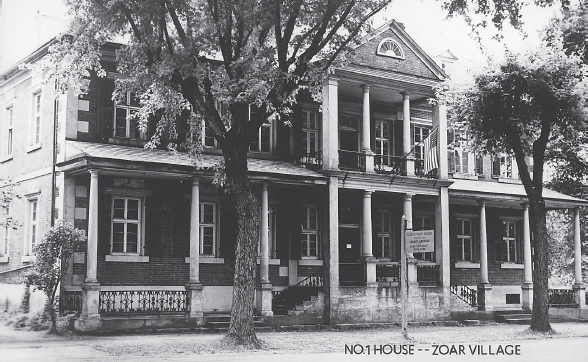

At that moment I understood: the commune of Zoar didn’t survive the new century of capitalism. At random I chose a room on the second floor. When the light shower stopped about thirty minutes later, from my window I watched the wooden town unfold like a flower. Everything brightened up. I walked down to the Zoar Store, built in 1833 and now operated by the Ohio Historical Society. It also operates eleven other buildings in town, including the Number One House, sewing shop, magazine complex, garden and greenhouse, dairy, and hotel.

Nowadays, residents live in the Zoarites’ original houses. They call Zoar a living village. Because the old architecture is still intact, Zoar is one of the few towns that can live in both the past and present. In one way, its past version is a ghost town. The Zoarites are gone; in their place live modern families who are not members of the founding sect. The Zoar Community Association, a group of residents and business people formed in 1967 to preserve the history and heritage of Zoar, operates a museum in the town hall. Anyone can rent the Zoar Schoolhouse for meetings, weddings, and special events. It is as if the modern residents are simply caretakers for a dead race.

The community is no longer self-sufficient; modern Zoar is a commuter and tourist town. Larger events include the Harvest Festival, Apfelfest, Christmas in Zoar, and the Spring Garden and Backyard Tour.

The village is still undeniably German, settled by Separatists who fled Wurttemberg with their mystic leader in search of religious freedom in America. They called themselves Separatists because they often opposed the state’s Lutheran Church for its formal doctrine. Originally, they were pietists, who believed in leading a purer life through individual rebirth and attaining a purer moral life through prayer meetings, Bible study, and attending Sunday school. When rationalism influenced church leaders in the 1700s, pietists separated from the Lutheran Church. Many of the Separatists were known as chiliasts, the believers in a doctrine of premillenialism (they thought Christ would return in 1836). Later, the sect drifted toward mysticism, and by 1791 it had grown larger, with dissenting pietists who opposed the new church hymnal as being too worldly. For breaking away, the Separatists were often harassed, imprisoned, and murdered by the state. Separatists did not accept sacraments such as confirmation, marriage, and baptism. They also opposed military service (a dangerous stance in the German states of the period), and the more radical members refused to pay taxes. A few of them practiced vegetarianism and celibacy.

Many of Zoar’s old buildings still stand, including the Number One House, built in 1835.

Zoar’s founders arrived in Ohio in a century when communes, some of them religious, were operating in rural areas across the United States. They included the Perfectionists of Oneida, New York; the Shakers at various sites in Ohio, Kentucky, and the East; the Harmonists at Economy, Pennsylvania; the communal societies of Aurora and Bethel in Missouri and Oregon; and the Amana Society in Iowa. German immigrants with spiritual leaders also founded the Aurora, Amana, and Harmony groups. But each one espoused different principles.

The Separatists needed a new home and found one in America. Each member sold his possessions to help pay for the voyage. In August 1817, they arrived in Philadelphia. Assisted there by Quakers, the group arranged to borrow money to buy land. The Quakers suggested they settle in Ohio. In October, the members arrived in the Tuscarawas River Valley to build a village, which they named Zoar in honor of the place where Lot went after fleeing Sodom in biblical times. Over the next fifteen years, the Zoarites bought fifty-five hundred acres to farm. Their emblem became the seven-pointed star of Bethlehem; their symbol, the acorn.

The Zoarites lived as a commune after their early attempts at farming failed. Unlike other communal groups, which operated this way for political or religious reasons, the Zoarites did it for practical purposes; they knew no other way to survive. All property and earnings became common stock. On April 19, 1819, 53 men and 104 women established the Society of Separatists of Zoar, under the leadership of Joseph Baumeler (later spelled Bimeler), their agent and spiritual leader. He disliked ministers, saying they knew books but not God. He discouraged marriage (but in fact he was married with children). He and his followers did not use prayer books; they thought they were harmful and preachers deceitful. And members were ahead of their time in one way: Men and women held equal rights in making community decisions, and women worked in the fields alongside the men.

Despite having some success raising crops, the Zoarites needed more money to stay in business. In 1827, the group decided to contract with the state to dig the Ohio and Erie Canal, which would pass through their land. Most communities allowed the state to dig the canals, but the hardworking Zoarites recognized the coming of the canal as a means of getting out of debt. When members finished the difficult work in 1828, they earned $21,000—more than enough to pay the $16,500 mortgage that they owed the Quakers. Because the canal ran next to the town, the Zoarites knew they could make money from commerce. They operated four canal boats, provided services to canal travelers, and sold their surplus goods. In 1835, the society became practically self-sufficient and increasingly wealthy. Seventeen years later, its property was valued at more than one million dollars—a substantial sum in those days.

Unfortunately, the society had little time to enjoy its good fortune. Bimeler died in 1853, leaving the group without its leader. On top of that, canal traffic started to decline. But it took decades for Zoar to die as a communal society.

At its peak, Zoar was green and prosperous. Apple trees grew everywhere. Members loved flowers and planted them in large gardens in the center of town, where they grew vegetables, flowers, and small fruits. On an entire block, they built the Zoar Garden and Greenhouse in 1835. It symbolized the new Jerusalem described in the Revelation of John. In the center—called the Centrum—stood a Norway spruce, representing everlasting life; a surrounding arbor signified heaven. Around the spruce stood twelve juniper trees, representing the twelve apostles. A circular walk enclosed the Centrum, from which twelve other walks led farther into the four corners of the garden, denoting the various paths to heaven. From each of these paths led smaller ones, like the worldly paths that people take as they seek the Lord’s salvation. Yet another, wider path went around the whole garden, to show the path of unredeemed souls.

The Zoarites grew flowers for their own enjoyment in the early years, but later they grew them commercially for markets in Cleveland and other places across the Midwest. Gradually, the society at Zoar branched into many different moneymaking operations. In the 1840s, at its peak of five hundred members, the community baked; made soap; grew grapes for wine; worked on the canal boats; brewed beer; raised and sold chickens and hogs (this was before they decided against eating pork); forged iron products; made pottery; milled flour; raised sheep for the wool; produced milk and butter; sewed clothing; and built stoves, tools, plows, and wagons. They also operated a general store and hotel that catered to outsiders.

Filled with their success, the Zoarites expanded. Dallas Bogan of the Warren County Historical Society in southwest Ohio told me he believes the Zoarites founded another town called Zoar in his county in the 1840s, although firm evidence linking the two towns is lacking.

Warren County’s Zoar prospered immediately, keeping busy two blacksmith shops and two wagon makers’ shops that employed eight to ten laborers. According to History of Warren County, Ohio, “Prosperity was destined only to be transitory. The streets of Zoar became long ago deserted and the sound of the hammer is no longer heard within her borders.” Until now, that is. When I drove through the ghost town on U.S. Route 22 / State Route 3, I noticed development all around me. Now, suburban people are fleeing to Zoar because it is only about five miles from Interstate 71. The rest of Zoar consists mostly of a few small brick and wooden houses built from the 1930s to the 1960s, the Zoar United Methodist Church, St. Philip’s Catholic Church, a storage building, and a body shop. Nothing remains of the old town.

Tuscarawas County was much better suited to a long-lasting town because it offered prime farmland, the canal, and the church elders. Yet visitors of the period must have considered the Zoarites an odd sect. After all, what Christian people disregarded baptism and the Lord’s Supper? What kind of gentleman wanted no titles—not even mister? Kept his hat on in a public room? Called a sermon anything but a sermon? Because the Zoarites believed all men were equal, members nei ther tipped their hats nor bowed. They did not mark their graves. They worked on Christmas, Easter, Sundays, and holidays, which they barely considered. The Zoar women, who outnumbered the men three to one at one point, were largely responsible for digging out much of the canal. Residents’ homes were numbered, but not in sequence; when people moved to another house, they took their number with them. (The Zoarites wanted to simplify everything, so they identified their buildings by numbers, not names.) Members were also obsessed with cleanliness. They scoured and scrubbed the village daily—even the trees. They removed and washed windows every day. They used two soaps—toilet soap for the face and a homemade soap for the body. Members caught using the more expensive toilet soap on their bodies received a reprimand. They drank beer—no, savored it. Never too happy with marriage, by the 1820s they embraced celibacy to give women more time to work on the canal. The Zoarites believed that God only tolerated marriage, and that it caused trouble in the community, but they did not forbid members from marrying. Celibate members divided themselves into houses of twenty each—for men, women, or both. They lived by the twelve Principles of the Separatists, including this one (number nine): “All intercourse of the sexes, except what is necessary to the perpetuation of the species, we hold to be sinful and contrary to the order and command of God. Complete virginity or entire cessation of sexual commerce is more commendable than marriage.”

When children reached age three, they were placed in community nurseries until they turned fourteen. (In 1840, one of the town trustees refused to send his children to the nursery, so the town dropped the requirement. By 1860, the practice died out.) The idea was to free the women to work outside their homes. Mothers and fathers did not see their children too often in those days. Rearing the children was left to the nursery supervisors; some were harsh and cruel. They insisted that the children earn their room and board by performing household tasks. Children lived in quarters that were hot and humid in the summer and cold in the winter. The early Zoarites believed a kiss was sinful and didn’t even believe in kissing their children.

While visiting the community in 1875 to write The Communistic Societies of the United States, reporter and author Charles Nordhoff couldn’t reconcile many of the Zoarites’ odd practices. He decided that he would not want to live in such a place. He wrote:

Yet, when I had left Zoar, and was compelled to wait for an hour at the railroad station, listening to men cursing in the presence of women and children; when I saw how much roughness there is in the life of the country people, I concluded that, rude and uninviting as the life in Zoar seemed to me, it was perhaps still a step higher, more decent, more free from disagreeables, and upon a higher moral scale, than the average life in the surrounding country. And if this is true, the community life has even here achieved moral results, as it certainly has material, worthy of the effort.

After visiting a dozen communal towns across America, Nordoff considered Zoar a town filled with dull and lethargic people:

Though founded fifty-six years ago, [it] remains without regularity of design; the houses are for the most part in need of paint; and there is about the place a general air of neglect and lack of order, a shabbiness, which I noticed also in the Aurora community in Oregon, and which shocks one who has but lately visited the Shakers and Rappists.

The Zoarites have achieved comfort—according to the German peasant’s notion—and wealth. They are relieved from severe toil, and have driven the wolf permanently from their doors. Much more they have accomplished; but they have not been taught the need of more. They are sober, quiet, and orderly, very industrious, economical, and the amount of ingenuity and business skill which they have developed is quite remarkable.

In 1884, the town incorporated as a village, with an elected mayor, council, and secretary-treasurer. The religious society continued to function, without the commune. By 1898, when it was obvious that the boom times of the canal were never coming back, the members disbanded the society. Each received land, a house, and possessions.

Zoar became just another declining canal town with an unusual name.

I walked over to the Zoar Store and asked to go along on a group tour. A historical society guide named Steve Shonk, of Navarre, escorted us on a tour that he gives four days a week. He dressed in the style of Zoarite clothing that was typical in the 1850s, complete with broad-brimmed straw hat and white linen shirt and dark trousers.

While walking around town with him, for a moment I forgot that he was not a Zoarite. He was precise in his terms and explanations, and appreciative but not adoring of what the sect accomplished.

We walked along the damp blacktopped streets while Shonk talked. When he’s not leading tours, he is writing the Zoar Star, a newsletter published quarterly by the Zoar Community Association.

The Zoar Store was built in 1833 at Main and Second Streets. The building served as the group’s business headquarters, post office, and store. The early residents had so little money that they had to sell homemade utensils and other useful things to the farmers and hired men of the area.

“I don’t know if there was any friction between the people of Zoar and the people of the county, but there was a healthy curiosity,” Shonk said as we walked between the buildings. “They all did business together. They didn’t have time for animosity. German immigrants were often sent straight to Zoar because they could find work there and speak the language. Newcomers would find out about the communal arrangement soon enough. Some didn’t mind it. They’d stay on. Others would leave for Dover and Canton and other area towns.

“Zoar hired a lot of outside laborers. The town welcomed some of them, but some others were not received so well. This had more to do with practical matters than religious. In 1834, thirty-five to fifty villagers were claimed in a cholera epidemic. The town was left shorthanded. The Zoarites decided to hire outside laborers. Some of the elders were against the idea, fearing the effects of outside influences, but the group had no choice. They needed help. They decided to accept only Germans—poor ones who had less to leave behind in the world. The Germans were sought because of the cultural similarities. A man could join at age twenty-one, a woman at age eighteen. Of course, they could live in Zoar and not become a member of the religious sect. They simply received a wage and were not included in the ownership of the community. In 1847, a big wave of immigrants came over from Germany. They settled here. Some were not Separatists, but they ended up staying anyway. One of those families was Catholic. It didn’t matter. Anyone could attend services in Zoar.”

We passed the cobbler shop, a large wooden building where cobblers made and repaired all the shoes for the community. The frame building, constructed in 1828, is now the Cobbler Shop Bed and Breakfast. In back, owner Sandy Worley uses the original wash house (where all the laundry for the Zoar Hotel was done) for storage.

At Main and Second Streets, the hotel is the most gothic of all the buildings, with a large cupola, wide front porch, and dormer windows on the third floor. The building awaits renovation by the state historical society. Initially, it had forty sleeping rooms and a huge dining room. People of all income levels stayed there; many arrived by canal boat. Wealthy people from Cleveland came to town in the winter to observe how the Zoarites operated their greenhouses. (They heated them with coal.) All outsiders, whether multimillionaire, middle class, or poor, ate in the hotel dining room. No class distinctions were recognized; even a beggar ate here, and President William McKinley stayed more than one night. People used to walk up the winding stairway to the observatory or tower to meditate.

“The canal, the woolen mill, and the tin shop practically supported the town,” Shonk said. “The people of Zoar mined the hills around the town and operated a foundry and two iron furnaces. After a slow start, they started making money and paid off their debts. They weren’t afraid of hard work, and they knew how to invest. At one time, Zoar had one of Tuscarawas County’s highest tax bills, because the commune owned so many acres. Back in Germany, the group got into trouble for refusing to pay taxes. They didn’t want their money to support the army. In this country, they didn’t have that problem. They had no problem paying their taxes.”

As we passed the oddly shaped buildings, most of them built by the people of Zoar, I asked Shonk about the town’s legacy. He thought for a moment and said, “Its legacy is in its buildings. Their houses still remain. Their furniture remains. They left us those things. It’s fortunate that enough descendants were left to donate artifacts to the state when the community was being restored twenty years ago. We lost a few buildings to lack of use, but we still have a town and it looks much the way it did when the commune was running. It is living history to us.”

Over night, the air turned cool. A misty rain fell across the fields. After a quiet, restful night at the Cowger House, I walked over to the log cabin that Mary and Ed Cowger also owned and operated as a smaller bed and breakfast. Although the couple, then in their fifties, enjoyed meeting people, they were also in a demanding business; taking care of two bed and breakfasts required a lot of time and energy. They had been in the business since they came to Zoar in 1984 and opened the Cowger House. They later bought the cabin (built in 1817) and the first schoolhouse (1833).

As candles burned brightly on the rugged pine table, I talked in the cabin’s main room, the dining room, and waited for the couple to serve a full breakfast. At 10 A.M., they walked in carrying poached eggs, sausage, biscuits, hash browns, hot tea, and orange juice.

Scanning the room, I noticed that every piece of furniture was original, at least a century old. I walked across the wood-plank floors to read a framed letter on the wall from a Civil War soldier who wrote that he could see hands and feet of dead comrades sticking out of burial grounds. The letter was just a small part of the walls’ wealth of memorabilia: old photographs, the hides of two foxes, old proclamations, a horse collar, candles, a butter churn, a musket, and an ammunition horn. “It probably looks better than when the Zoarites were here,” Ed said.

The retired history teacher and his wife sat directly across the table, watching expectantly while I ate at a tavern table made in 1850. Although this was June, the morning was gray and drizzly. The candle on the table provided a fretful light in the dim cabin. The couple seemed to be waiting for me to say something profound.

“Is it what you expected?” Mary asked.

All I could reply was, “Yes. Good.” I felt a bit claustrophobic but managed to smile.

Ed said, “In the old days, innkeepers didn’t have to be nice to you. They didn’t even have to give you a bed. In Zoar, the first hotel opened in 1829. The building we are in was the brewmaster’s home.”

“To tell you how important he was,” Mary added. “His was the second house built in town.”

“The idea was, everyone had to work,” Ed said. “They met at the assembly house every morning to find out where they had to work that day. They’d keep their children at the dormitory. The children didn’t like the place, and didn’t like the way they were treated. When one child died, the mother claimed he died of a broken heart.”

The Cowgers spoke as if they personally knew the Zoarites, as if the German neighbors were still alive. The candles flickered lower. They saw the notebook at my side and asked if I wanted to write about the house. Mary was eager to talk.

“When we first came here twenty years ago, a woman who owned Number Thirteen welcomed us to the community,” she said. “She asked me, ‘Are you Christian?’ We said, ‘Yes.’ She asked me three times. She said, ‘Do you feel you were drawn here?’ We said, ‘Yes.’ She said the town was different. We thought she was joking.

“Then one day we went to a meeting in the tavern and meeting hall. The building once had a huge horseshoe bar. We came down the steps to the tavern and I went to open my mouth and people surrounded us. I thought, Is this place possessed? They started talking about the ghosts of Zoar. A man said, ‘Do you believe in ghosts?’ I said, ‘Not yet!’ He said, ‘Don’t be too sure. If a ghost likes you, he will follow you all around from place to place.’ Then they proceeded to all talk about their ghosts and how things were moved around their homes. It was like living in an episode of The Twilight Zone.”

The Cowgers wondered what to do. They had already spent their savings to buy the property. They talked with a neighbor who had also come to town looking for a relaxing and meaningful life; she had opened a bed and breakfast in the old dormitory building. She told them that the gothic dormitory was a magnet of negativity, as if all the frustration and hurt feelings of the Zoarites had built up inside its walls and were never released. “So many strange things happened there in the dorm,” Mary said. “Another owner was walking up to the attic and passed his two boys. He turned around and saw a white mist following them down the stairs. The man was no kook; he was a former FBI agent. He was shaken up by it. We leased the boys’ dorm for a time and stayed there, and our daughter claimed she heard a baby crying. There was no baby.”

At this point, the Cowgers broke the news to me: a ghost lives in their inn—the one in which I had slept the night before. Sometimes he appears as a dark figure. The couple calls him George. He also appears in the annex cabin, where I was having breakfast. Visitors have reported seeing the man dressed in an old-fashioned, purple robe. That’s not all. “A friend of ours told us he thought he saw something white drift by, and once somebody tapped him on the shoulder,” Mary said. “Our friend was painting in the inn at the time. He left his paints and ran away. He was reluctant to tell the story, but I got it out of him finally. I asked him about it, and he said, ‘This frightens me.’”

Ed said, “People say they hear parties, the clinking of German steins. I was skeptical, but one day I thought I heard the clinking and I yelled, ‘Das ist gut!’ I didn’t hear them for a time.”

By now, I was feeling uncomfortable. Mary went on: “One time, after a candlelight dinner, somebody asked about ghosts in our main house. A man said, ‘My wife and I were on the top of the stairs and we saw a man this morning. He had long, white hair.’ His wife added, ‘The Quaker Oats ghost!’ Then the man said, ‘He was dressed in a purple coat and he went through the door but it didn’t slam.’ I told this to my friend Jenny, who lives across the street, and she said she had seen the man in the window, wearing purple. He must follow us from house to house.’”

A year later, the Cowgers learned a clue about the spirit’s identity from a guest who stayed in the cabin. He said his father bought it in 1949 at a sheriff’s sale and owned it for several years. The guest, a colonel in his sixties, explained to the couple that his father loved the cabin. He saw some meaning in the talk about the robe, saying his father once went to Japan and bought an unusual purple robe. He wore it in the log house frequently. Mary said, “That story gave me the chills.”

Ed excused himself. I noticed that it was still dark inside the cabin, but outside the sun had started shining. Ed returned minutes later with a black-and-white photograph of a white-haired Cleveland physician who had also enjoyed the cabin years earlier. He loved it so much, in fact, that his family buried his ashes in the cabin’s backyard. He is not the purple-robe ghost, but another spirit who can’t let go. Ed said, “I suspect it is the doctor who we have seen around here, too. We have several guests who require no pampering whatsoever.”

“Maybe the doctor makes house calls,” I told him.

Someone does. About 1:30 A.M. several years ago, Mary was painting in an upstairs room in the cabin. Ed had already grown tired and left for the couple’s main house. She remained to finish the room. “Fifteen minutes later, the front door opened,” she said. “I know how that old thing sounds; it’s loud and it sticks. I heard hard-soled shoes, heavy footsteps, coming up the steps. I could feel them getting closer. Then a man’s voice yelled, ‘Honey, I’m back.’ Naturally, I thought it was Ed, so I said, ‘OK. I’m finishing up.’ Then suddenly I realized: Ed had been wearing tennis shoes. And Ed never calls me honey. Nervously, I called his name, and got no answer. Then I got shook. I grabbed the telephone and called Ed. When he answered, I said, ‘Uh-oh.’ He said, ‘I’m on my way.’ I was even more shook up when I remembered that I had locked the door when Ed left. No one could have entered that house from the outside.”

Other strange occurrences have rattled the Cowgers over the years. Ed took a new roll of toilet paper to the guest room in the cabin. No guests were staying in the house that night, yet the next morning the paper had been removed from the roll and piled neatly down the stairs. A ghostly cat, perhaps?

Mary said, “I told him, ‘Now, explain that, Mr. Logical.’”

“Of course, I couldn’t,” he admitted.

Mary said, “I was raised with Christian beliefs. I believe you go to heaven or hell. So I have a hard time believing in ghosts. The Bible talks of evil spirits. If you believe what the Bible says, you’ve got to believe those are evil spirits. Or maybe good. All I know is, I’ve seen these things and I don’t like the experience. Leave me alone! I don’t want ghosts playing with me.”

“What if there are different dimensions, and for a few seconds they lock in and we can see each another as though we’re staring through a screen door?” Ed said. He paused for a moment to reflect, and said, “Where do they end?”

I couldn’t help but think of his theory as I shook his hand and walked down the creaky stairs, passing the hallway where the Cowgers had seen the shadow man. All I noticed there was warm air striking my face from a window, and the sun coming up over the canal.