VI

THE ADAPTATION OF THE FAMILY TO THE CHILD1

THE title which I have given to this paper is rather an unusual one, for we are generally concerned with the adaptation of the child to the family, not that of the family to the child; but our special studies in psycho-analysis have shown that it is we who should make the first adaptation, and that we have in fact made the first step in this direction, which of course is to understand the child. Psycho-analysis is often reproached for being too exclusively concerned with pathological material; this is true, but we learn much from a study of the abnormal that is of value when applied to the normal. In the same way the study of the physiology of the brain would never have advanced so far as it has without a knowledge of the processes of faulty function; by a study of neurotics and psychotics psycho-analysis shows the way in which the different levels or layers, or the different ways of functioning, are hidden behind the surface of normality. In the study of the primitive or the child we find traits which are invisible in more civilized people; indeed we stand in debt to children for the light they have thrown on psychology, and the best and most logical way of repaying that debt (it is in our interest as well as theirs to do so) is to strive to improve our understanding of them through psycho-analytical studies.

I confess that we are not yet in a position to assess precisely the educational value of psycho-analysis, nor to give rules regarding practical details of education, because psycho-analysis, which is ever cautious in giving advice, is primarily concerned with matters which education has either mishandled or left untouched; we can tell you how not to educate your child better than we can tell you how to do it; the latter is a much more complicated question, but we are hoping that we shall be able some day to give a satisfactory answer to that too. For this reason in what I have to say I am compelled to be more general in my treatment of the subject than I would like, but I can say that the study of criminals, or normal people, or neurotics, will not be complete until we have made further progress in the analytical understanding of the life of the child.

The adjustment of the family to the child cannot take place until the parents first of all understand themselves and thus get some grasp of the mental life of grown-ups. Up to now it has often been taken for granted that parents are endowed with a natural knowledge of how to bring up their children, though there is a famous German saying which states the opposite: ‘It is easy to become a father, but difficult to be one.’ The first mistake that parents make is to forget their own childhood. Even in most normal people we find an astonishing lack of memories from the first five years of life, and in pathological cases the amnesia is even more extensive. These are years in which the child has in many ways reached the level of adults—and yet they are forgotten! Lack of understanding of their own childhood proves to be the greatest hindrance to parents grasping the essential questions of education.

Before I come to my real topic—the question of education—let me make a few general remarks on adaptation and its part in psychic life. I have used the word ‘adaptation’, and I do so because it is a biological term and draws our attention to biological concepts. It has three different meanings—the Darwinian, the Lamarckian, and a third which can be called the psychological. The first deals with natural selection, and is at bottom a ‘statistical explanation’ of adaptation in that it concerns itself with general questions of survival. For example, the giraffe, having a longer neck, can reach food that shorter-necked animals cannot; it can therefore satisfy its hunger and live to propagate its kind; this explanation is in fact applicable to all creatures. According to the Lamarckian view, the exercise of a function both helps the individual to become stronger and passes on the increased capacity to posterity; this is a ‘physiological explanation’ of adaptation. There is a third way in which individuals can adapt themselves to their environment, and that is by psychological means. It is probable that alteration in the distribution of mental or nervous energies may make an organ grow or degenerate. It has become fashionable in America to deny the existence of psychology as a science; every word beginning with ‘psych-’ is a brand-mark of the unscientific, on the ground that psychology contains a mystic element. Dr. Watson once asked me to say just what psycho-analysis was. I had to confess that it was not so ‘scientific’ as behaviourism, viewing science, that is to say, solely as a discipline of the measure and scales. Physiology requires that every change should be measured with an instrument, but psycho-analysis is not in a position to deal with emotional forces in this way. Very slight approaches, it is true, have been made to this goal, but they are at present far from satisfying. However, if one explanation fails, it is not forbidden to try others. One such we owe to Freud. He found that by a scientific grouping of the data of introspection one could gain a new insight just as certainly as by grouping the data of external perceptions derived from observations and experiments; these introspective facts, though as yet not measurable, are none the less facts, and as such we have the right to group them and try to find out ways of helping us to something new. By merely regrouping introspective material Freud constructed a psychical system; in this there are of course hypotheses, but these are found no less in the natural sciences. Among them the concept of the unconscious plays a very special part, and with its help we have reached conclusions which were not possible with the hypotheses of physiology and cerebral anatomy. When progress in microscopy and chemistry shows us that Freud’s hypotheses are superfluous we shall be ready to resign our claims to science. Dr. Watson is of the opinion that one can understand the child without the help of psychology; he thinks that psychology is unscientific and that conditioned reflexes can explain behaviour fully. I had to answer him that his physiological scheme may lead to an understanding of white mice and rabbits, but not of human beings. But even with his animals he himself is, without admitting it, constantly using psychology—he is an unconscious psycho-analyst! For instance, when he speaks of a fear reflex he uses the psychological term ‘fear’. He uses the word correctly because he knows from introspection what fear is; if he had not known it introspectively he would not have realized what running away meant to the mouse. But to return to the question of adaptation: psycho-analysis brings forward a new series of facts besides those of the natural sciences—the working of internalfactors which cannot be detected except through introspection.

I will now try to deal with the practical problems connected with the ways in which parents adapt themselves to their children. Nature is very careless; she does not care for the individual, but we human beings arc different; we wish to save the lives of every one of our offspring and spare them unnecessary suffering. Let us therefore turn our special attention to those phases of evolution in which the child has to deal with difficulties. There are a great many of them. The first difficulty is birth itself. It was Freud himself who told us that the symptoms of anxiety were closely connected with the particular physiological changes which take place at the moment of the transition from the mother’s womb to the external world. One of his former pupils used this view of Freud’s as a springboard from which to leap to a new theory, and, leaving psycho-analytical concepts behind him, tried to explain the neuroses and psychoses from this first great trauma; he called it ‘the trauma of Birth’. I myself was very much interested in this question, but the more I observed the more I realized that for none of the developments and changes which life brings was the individual so well prepared as for birth. Physiology and the instincts of the parents go to make this transition as smooth as possible. It would indeed be a trauma if lungs and heart were not so well developed, whereas birth is a sort of triumph for the child and must surely exert as such an influence on its whole life. Consider the details: the menacing suffocation is dealt with, for the lungs are there and begin to expand at the very moment of the cessation of the umbilical circulation, and at the same time the left side of the heart, till then inert, takes up its role with vigour. In addition to these physiological aids, the parents’ instincts guide them to make the situation as agreeable as possible, the child is kept warm and protected from the disturbing stimuli of light and sound as far as possible; indeed they make the child forget what has happened, it can make believe that nothing has happened. It is questionable whether an event dealt with so smoothly and speedily should be called a ‘trauma’.

Real traumata are more difficult to solve; they are less physiological than birth, they concern the child’s entry into the company of his fellow mortals; the intuitions of the parents do not make such good provision in this respect as they did at birth. I refer to the traumata of weaning, training to cleanliness, the breaking of ‘bad habits’, and, last and most important of all, that breaking off from childhood itself into the adult way of life. These are the biggest traumata of childhood, and for these neither parents in particular nor civilization in general have as yet made adequate preparation.

Weaning is and always has been an important matter in medicine. It is not only the change from a primitive way of feeding to the active act of mastication, that is, it is a change not only of physiological, but also of great psychological, importance. A clumsy method of weaning may influence unfavourably the child’s relation to his love objects and his ways of obtaining pleasure from them, and this may darken a large part of his life. We do not, it is true, know much about the psychology of the one-year-old child, but we are beginning to get a faint conception of the deeper impressions which weaning may leave. In the early states of embryonic development a slight wound, the mere prick of a pin, can not only cause severe alterations in, but may completely prevent, the development of whole limbs of the body. Just as, if you have only one candle in a room and put your hand near the candle, half the room may become darkened, so if, near the beginning of life, you do only a little harm to a child, it may cast a shadow over the whole of its life. It is important to realize how sensitive children are; but parents do not believe this, they simply cannot comprehend the high degree of sensitivity of their offspring, and behave in their presence as if the children understood nothing of the emotional scenes going on around them. If intimate parental intercourse is observed by the child in the first or second year of life, when its capacity for excitement is already there but it lacks as yet adequate outlets for its emotion, an infantile neurosis may result which may permanently weaken the child’s effective life. Infantile phobias and hysterical anxieties are common in the early developmental years; usually they pass without disturbing later life, but quite often we find that they have left deep impressions on the mind and character of the child. This much for the more or less passive relation of the parents to the young; we must now examine a situation or series of situations in which the parents play an active part in the intimate concerns of the child’s emotional life, and it is here especially that we find how necessary it is for the parents to understand their own minds and instinctual reactions before they embark on the task of ‘upbringing’.

Toilet training is one of the most difficult phases in the child’s development. It is one that can be very dangerous, but it is not always so; there are children who are so healthy and well equipped that they can deal with the silliest parents, but these are exceptions, and even if apparently successful in dealing with their bad upbringing we too often note that they have lost something of the happiness which life can bring. The possibility of loss of happiness through careless or over-vigorous ‘training’ in cleanliness should make parents and educators pay far more attention than they do to the feelings of the child and appreciate its difficulties. Freud’s observations on the emotional changes in the child during the adaptations to the adult code of cleanliness led him to the signal discovery that an important part of the character of the individual is formed during this process. To put it in other words: the way in which the individual adapts his primitive urges to the requirements of civilization in the first five years of life will determine the way in which he deals with all his difficulties in later life. Character is from the point of view of the psycho-analyst a sort of abnormality, a kind of mechanization of a particular way of reaction, rather similar to an obsessional symptom. We expect an individual to be able to adapt himself precisely to the details of the current situation, but consider how far this is compatible with what his character has made out of him! If you know the character of any individual, you can make him perform an action when you wish and as often as you wish, because he behaves like a machine. If you put something into his ear he will shake his head, if you utter a particular name you know he will also shake his head (physical and psychical reflex, i.e. automatic response). He gives this automatic response to your cunningly chosen word because it is ‘in his character’ to do so. When I was a student too much importance was accorded in medicine to inherited characteristics; physicians believed that we were the product of our constitution. Charcot, one of our best teachers in Paris, gave many important lectures on this topic I well remember a typical incident which illustrates this. One day a mother came to him at one of his leçons du mardi and wished to speak to him about her neurotic child. He began, as always, to ask about its grandfather and what diseases he had and what he died of, and about its grandmother and the other grandfather and grandmother and all its relations: the mother tried to interrupt and tell him of something that had happened to the child a week or a year ago. Charcot became irritated, and did not want to hear about this; he was intent on tracing the inherited characteristics. We psycho-analysts do not deny their importance; on the contrary we believe them to be among the most important factors in the aetiology of neurotic or psychotic disease, but not the only ones. The inherited disposition may be there, but its influence may be modified by post-natal experience or by education. Both heredity and the individual traumata must be taken into account. Cleanliness is not a thing inborn, it is not an inherited quality, so it must be taught. I do not mean that children are not sensitive to this sort of teaching, but I think that, unless taught, children would not acquire this training by themselves.

The natural tendency of the baby is to love himself and to love all those things which he regards as parts of himself; his excreta are really part of himself, a transitional something between him and his environment, i.e. between subject and object. The child has a sort of affection for his excrement; in fact some adult people share this attitude too. I have sometimes analysed so-called normal people, and I have never found very much difference in this respect between them and the neurotics, unless it be that the latter have somewhat more unconscious interest in dirt; and since hysteria is the negative of a perversion, as Freud has taught us, cleanliness in a normal man is founded on his (repressed) interest in dirt. People generally call it abnormal if a person is interested in the excretory functions, but most of us are to a certain extent during the whole of our lives. Do not let us be downhearted about it, for these primitive functions provide us with energy for the great achievements of civilization. If we ignore this and rage cruelly and blindly against the child struggling with difficulties—achieving the repression of these difficulties—we shall only deflect the energies to false paths. The reaction will differ according to the varying constitutions of the individuals; one will possibly become a neurotic, another a psychotic, a third a criminal. If, however, we know our way in these matters and treat the children with understanding, let them work out their impulses in their own way to a certain extent, and by giving way give them a chance to sublimate those impulses, the path will be much smoother and they will learn to turn their primitive urges into the paths of usefulness. Teachers often wish to ‘weed out’ these primitive urges (which are most important sources of energy) as if they were vices, whereas if led into social channels they can be used for the good of the individual and for the benefit of society.

The real traumas during the adaptation of the family to the child happen in its transitional stages from the earliest primitive childhood to civilization, not only from the point of view of cleanliness, but from the point of view of sexuality. One often hears people saying that Freud bases everything on sexuality, which is quite untrue. He speaks of the conflict between egoistic and sexual tendencies, and even holds that the former are the stronger. Psycho-analysts in fact spend most of their time in the analysis of the repressing factors in the individual.

Sexuality does not begin with puberty, but with the ‘bad habits’ of children. These ‘bad habits’, as they have been erroneously called, are manifestations of auto-eroticism, that is of primitive sexual instincts in the child. Do not be afraid of these manifestations. The word masturbation frightens people immensely. If, in consultation—and how often this happens—the doctor’s advice is asked about the auto-erotic activities of children, he should tell the parents not to take it tragically; parents, however, have to be treated tactfully in this matter because of their immense fears and their lack of comprehension. Curiously, what the parents do not comprehend is precisely what the children understand only too well and experience deeply, and what the children cannot fathom is as clear as daylight to the parents. I will explain this riddle later on: it contains the whole secret of the confusion in the relation between parents and child.

I will turn for a moment from this paradox to the salient question of how to deal with the neurotic child. There is only one way of doing this, and that is to find out his motives, which, though hidden in his unconscious mind, are nevertheless active. Several attempts have already been made in this direction; a former pupil of mine and of Dr. Abraham’s, Mrs. Melanie Klein, whose paper on ‘Criminal Tendencies in Normal Children’ appeared in this Journal, Vol, VII, 11, pp. 177–92, has courageously attempted the analysis of children as if they were adults, and has met with great success. Another attempt, on different, more conservative, lines has been made by Miss Anna Freud, Professor Freud’s daughter. The two methods are quite different; we shall see some day whether they can be brought together and the difficult problem of a combination of education and analysis solved; at any rate we can say that the beginnings are hopeful.

When in America recently I had an opportunity of studying the methods of a school which is run by psycho-analytically trained and mostly psycho-analysed teachers. This is the Waiden school. The teachers try to deal with the children in groups, since separate individual analysis of each child, which would be preferable, is out of the question on account of time. They attempt to educate children in such a way that analysis becomes unnecessary. If they have a really neurotic child they make, of course, a particular study of it, giving it an individual analysis and as much individual attention as it requires. In particular I was greatly interested in the way in which they deal with sex education. The school emphasizes in its conferences with parents the need for answering children’s questions on sex in a simple, natural way. Unfortunately they adopt the ‘Botanic Method’, i.e. they use plant analogies in explaining reproduction in the human species.

I have an objection to make against this. It is too informative, that is, not sufficiently psychological, in its appraoch. It may be a good beginning, but it does not give full consideration to the internal needs and strivings of the child. For instance, even the most elaborate and physiological explanation of where children come from does not satisfy the child, and the usual way in which children react to this information is by sheer disbelief. They virtually say: ‘You tell me this, but I don’t believe it.’ What the child really needs is an admission of the erotic (sensual) importance of the genital organs. The child is not the scientist who wants to know where children come from; it is interested, of course, in this question as it is interested in astronomy, but it is much more desirous of having the admission from parents and educators that the genital organ has a libidinous function, and as long as this is not admitted by the parents no explanation is satisfactory to the child. The child puts to itself such questions as this: how often does sexual intercourse take place? and tries to compare the answer with the number of children in the family. Then he says, perhaps: ‘It must be very difficult to produce a child, because it lasts so long.’ It guesses that the sexual act occurs repeatedly, not once only, and that it causes pleasure to the parents; sympathetically, as we say, it feels erotic sensations in its own genitals which can be satisfied by certain activities, and it is clever enough to find out and to feel that the genital organ has a libidinous function. It feels guilty because it has libidinous sensations at this stage, and therefore thinks: ‘What an inferior person I am to have libidinous sensations in my genitals, whereas my respected parents only use this organ in order to have children.’ As long as the erotic or pleasurable function of the genital is not admitted, there will always be a distance between you and your child, and you will become an unattainable ideal in its eyes—or the reverse! This is what I meant by the paradox a few moments ago. The parents cannot believe that the child experiences in its genitals sensations similar to their own; whereas the child, just because of these sensations, feels corrupt and believes that the parents are in this respect pure and immaculate, which the parents find readily acceptable; there is thus a gulf between parent and child on this intimate domestic matter. If a similar gulf developed between a husband and wife—as in fact it not so seldom does—we should not be at all surprised that it led to an ‘estrangement’: but with the blindness which clouds our vision on nearly all matters connected with the sexual activity of children (due to our infantile amnesia) we expect implicit trust from children while denying them the validity of their own physical and psychical experiences. Often one of the child’s greatest difficulties arises later when it realizes that all this high idealization is unfounded, is not true, and it becomes disappointed and mistrusts every authority. One should not deprive the child of its trust in authority, in the truthfulness of its parents and others, but it should not be forced to take everything on trust. Perhaps I can illustrate this best by saying it in another way, that it is a disaster for a child to grow up to disbelieve, to be disappointed too early.

The Waiden school does good work, but of course it is only a beginning. Their method of influencing the child’s mind through the medium of the parents’ understanding is in some cases quite good, and in early cases of neurotic difficulties it might even be successful. We must remember that the first child analysis was done by Professor Freud in this way (Little Hans1). He interviewed the father of the neurotic child and all the explanations were given by the father. But the father was analysed by Freud, a fact likewise to be forgotten.

The difficulties of adaptation at the age when the child becomes independent of the family are very much connected with sexual development. This is the stage of the formation of the so-called Oedipus conflict. If you think of the ways in which children sometimes express themselves about this question, then you will probably not find it so tragic. The child sometimes spontaneously tells the father: ‘If you die, I shall marry Mother.’ Nobody takes it very seriously, because this is said at a time before the Oedipus conflict, that is to say at a period when the child is permitted to do and think everything without being punished for it, just because the parents do not comprehend the sexual nature of the child’s intentions. Suddenly the child, which until then had fully believed in its complete freedom, finds that at a certain age such things are taken seriously and are punished. In these circumstances the poor child reacts in a very particular way. To help you to understand this, I shall use a simple diagram of the human mind as explained by Freud:

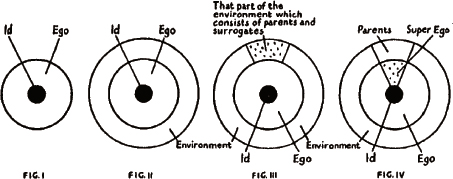

The Id (the instincts) is the central part, the Ego the adaptive peripheral part of the mind, the part which must adjust itself to the environment in any particular relationship. Human beings are a part of the environment, differing greatly in importance from all other objects in the world, particularly in one significant respect: all other objects are always equable, always constant. The only part of the environment which is not reliable is other persons, particularly the parents. If we leave something in any place we can find it again in the same place. Even animals do not vary greatly, they do not lie against their own natures; once known, they can be depended upon. The human being is the only animal which lies. It is this which makes it very difficult for a child to adapt itself to the parental part of its environment; even the most respected parents do not always tell the truth, they lie deliberately, though—as they think—only in the interests of the child. But once a child has experienced this it becomes suspicious. That is one difficulty. The other is the child’s dependence on its environment. It is because of the ideas and ideals of its environment that the child is forced to lie. Parents have here set a kind of trap for the child. The child’s first judgements are of course its own, that sweets are good, and being trained is bad; it then discovers that another set of standards is firmly implanted in the parents’ mind, namely that sweets are bad and being trained is good, and so forth. The former set is derived from its own perceptions of pleasant and unpleasant experience; the latter is thrust upon it by persons who, in spite of these views, are deeply loved. The child, being dependent on the parents both physically and emotionally, has to adapt itself to the new and difficult code. It does this in a particular way, which I will illustrate from a case. I had a patient who remembered his early life very well. He was not what we should call a good child, he was rather bad, and was beaten every week, sometimes in advance. When he was beaten he suddenly began to think consciously: ‘How nice it will be when I am a father and can beat my child!’, thus showing that in his fantasy he already enjoyed himself in his future role of father. An identification of this kind leads to a change in a part of the mind. The ego has become richer by acquiring from the environment something that was not inherited. This is also the way by which one becomes ‘conscientious’. First we are afraid of punishment, then we identify ourselves with the punishing authority. Then father and mother may lose their importance; the child has built up a sort of internal father and mother. This is what Freud calls the super-ego (see diagram).

The super-ego is thus the result of an interaction between the ego and the environment; if you are too strict you can make the life of a child unnecessarily difficult by giving it a too harsh super-ego, I think it will be necessary at some time to write a book not only about the importance and the usefulness of ideals for the child, but also about the harmfulness of exaggerated ideals. In America children are very disappointed when they hear that Washington never told a lie in his life. When one little American heard that Washington never lied, he asked: ‘What was the matter with him?’ I felt the same dejection when I learned at school that Epaminondas did not lie, even in joke—Necjoco quidem mentiretur.

I have only a few points to add. The question of co-education, which I had an opportunity to see working in America, reminds me of the time when I went with my friend Dr. Jones and some other psycho-analysts in America to listen to Freud’s first American lectures. We met Dr. Stanley Hall, the great American psychologist, who said to us jokingly: ‘You see these boys and girls, they are capable of living together for weeks at a time, and unfortunately it is always without any danger.’ This is more than a joke. The repression on which proper behaviour is founded may cause great difficulties in later life. If you think that co-education is necessary you must find a better way of bringing the sexes together, because the present method of herding them together socially and at the same time forcing them to repress their passionate emotions may enhance the development of neuroses. One word only about the ways of meting out punishment at schools: I only want to stress how necessary it is to get rid of the spirit of retaliation, instead of making it just an educational measure.

The idea I had when accepting your invitation was not to say something definitive about the relations between psycho-analysis and education, but just to stimulate you to further interest and further work. Freud called psycho-analysis a kind of re-education of the individual, but things seem to develop in such a way that education will have more to learn from psycho-analysis than psycho-analysis from education. Psycho-analysis will teach teachers and parents to treat children in a way which makes this ‘re-education’ superfluous.

[The following took part in the discussion: Dr. Ernest Jones, Mrs. Klein, Dr. Menon, Mrs. Susan Isaacs, Mr. Money-Kyrle, Miss Barbara Low, Dr. David Forsyth.

Dr. Ferenczi then replied as follows:]

In answer to Dr. Jones’s objection I regret that I gave the impression of agreeing that measurement is the sole qualification for classing a method as scientific. To begin by sharing the opinion of one’s opponents is the best way to overcome them, therefore I accepted it as a positum sed non concessum. Although I have a very high opinion of mathematics I really believe that even the best measurement would not make psychology unnecessary. Even if you had a machine that could project the subtlest processes of the brain on a screen, accurately registering every change of thought and emotion, you would still have an internal experience, and would have to connect the two. There is no way out of the difficulty other than to accept both kinds of experience, the physical and the psychical; to try to dispense with this duality is only to approach the unknown.

In reply to Mrs. Klein I can only agree that full freedom in fantasy would be an excellent relief for the whole of life, and if this could be granted to children they would the more easily adapt themselves to the required changes from their autistic activities to a life in a community. Therefore it is very good to allow children to have full freedom of fantasy, but in order to have it the parents must be on an equal level with the children and acknowledge that they themselves have the same sort of fantasies: this, however, does not excuse them from teaching the child the difference between fantasies and irrevocable actions. Where this freedom is granted there is a greater probability that the emotional difficulties of later life will be lessened. You must permit the fullest freedom to fantasy, that is to say you must lead the child to acknowledge in his fantasy that he is allowed to imagine superiority that he actually has not. He will try to take advantage of the situation, and then perhaps comes a point where you have to use your authority. Only unjustified authority is not permitted by psycho-analysis.

I am reminded of an incident with a little nephew of my own, whom I treated as leniently as, in my view, a psycho-analyst should. He took advantage of this and began to tease me, then wanted to beat me, and then to tease and beat me all the time. Psycho-analysis did not teach me to let him beat me ad infinitum, so I took him in my arms, holding him so that he was powerless to move, and said: ‘Now beat me if you can!’ He tried, could not, called me names, said that he hated me; I replied: ‘All right, go on, you may feel these things and say these things against me, but you must not beat me.’ In the end he realized my advantage in strength and his equality in fantasy, and we became good friends. In fantasy a child should be free, but not in action. That is the great lesson which education has to teach, namely where the limitation of action begins; it is not the same thing as repression, and it is not harmful for the future of the child to learn to control himself. The difficulty arises when the child begins in consequence to think that he does not want to do things.

With regard to the question how to translate symbols to children, we should in general learn symbols from children rather than they from us. Symbols are the language of children; they have not to be taught how to understand them. They have only to feel that the other person has the same understanding of them that they themselves have when acceptance becomes immediate.

I think that is all I can say to-night, and I hope this meeting will act as a stimulus to further work. I will conclude with a little story about Prof. Freud, who, when anyone comes to him with an objection, instead of entering into a discussion of it, replies: ‘Excellent, excellent, now write a paper about it and do not dissipate your interest in discussing the subject with me.’ Those are my parting words to you; if you make observations and have views on the adaptation of the family to the child—write a paper about them!