XXI

NOTES AND FRAGMENTS1

Editor’s Note

ON Ferenczi’s death a number of notes were found among his papers. These were jottings of ideas that were to be worked up later, if occasion arose, into more permanent form. They were for his private use, in the four languages which served as the medium of his thought, and were scribbled on odd bits of paper, using abbreviations for phrases and ideas which needed some effort to discover and correctly to transcribe.

Ferenczi’s literary executors translated the bulk of these notes into German (where that language was not originally used) and published them in the Bausteine, Vol. IV.

The originals were burnt when Ferenczi’s charming house in Buda was destroyed in the siege of 1944–5.

I (1920)

26.9.1920

Nocturnal Emission, Masturbation, and Coitus

1. Nocturnal emission is always unconscious masturbation (often brought about by means of unconscious fantasies).

2. It always follows as a substitute on the giving up of masturbation. In some cases masturbation in sleep slips in as a transitory stage.

3. Complementary series. Onanism=masturbation+fantasy. The more the masturbation, the smaller the role played by fantasy, and vice versa. Fantasy is more exhausting, both physically and morally.

4. Therapy: nocturnal emission can be changed into onanism, and it is only the onanism that can be converted into coitus.

5. Precocious ejaculation reduces the friction to a minimum and increases to the extreme the mental aspects of the emotion (and of fantasy). It corresponds to a diurnal emission.

6. Forepleasure gratifications are as far as possible to be forbidden to patients suffering from precocious ejaculation.

7. The tendency to onanism is probably connected with increase of urethralism. (Tendency to ejaculation outweighs tendency to retention.) Such urethralism would be characteristic of the neurasthenic constitution, while the tendency to retention (anal-erotic) could go together with the constitution for anxiety neurosis. (Tendency to coitus reservatus, interruptus, incompletus.)

In the same way:

I/1. Urethral-erotic constitution=tendency to enuresis—tendency to onanism (to nocturnal emission).

2. Inordinately great discharge—manifestation of neurotic symptoms=impoverishment of the organ (or organs) in libido.

II/1. Anal-erotic constitution—tendency to retention.

2. Retention—anxiety neurosis (manifest).

What could the hypochondriac constitution be? Tendency to accumulate organ libido (organ eroticism). (Fixation to this eroticism).

Perhaps: already an accumulation of protonarcissistic (genital—anal and urethral—) libido in the organs.

26.9.20

‘Zuhälter’ and ‘Femme Entretenante’

Being kept by a prostitute is not simply ‘moral insanity’, but also fixation (regression) to the desire of being kept by the mother. Many impotents are unconsciously Zuhätter who cannot surrender in love to a woman if they have to give anything in return or sacrifice something. Amongst other things, ejaculation is such a sacrifice.

(Parallel: woman who keeps a man—mother type, one who provides, a cook.)

30.9.20

Anxiety and Free Floating Libido

The association of a patient brought a striking confirmation of the correctness of Freud’s ideas, according to which anxiety is to be explained by the libido becoming free and remaining unsatisfied: ‘My wife used to have fears when she had to fetch something from a dark room; her method of protection against this was to take her baby into the room with her; if she pressed the child to herself she did not feel any anxiety at all.’

The efficacy of this remedy proves to us ex iuvantibus that anxiety in this case was brought about by a relative frustration of libido satisfaction. This corresponds to a similar case described by Freud of a child who was not afraid in the dark if he could hear his mother speak. Hearing her voice, the darkness for him became ‘lighter’.

30.9.20

On Affect Hysteria

Exaggerated disgust is directed against everything that is in any way connected with genitality. (Fat women, over-full breasts, pregnancy, confinement, newly born babies.) Idiosyncrasies against certain kinds of food and drink.

‘Squandering of affect’ in the work of introjection.

Genital excitement is discharged in non-genital affects.

Conversion is (Breuer, Freud) also discharge of affect.

Conversion: an affect acquired ontogenetically.

Affect: conversion acquired phylogenetically.

Stigmas are trivial (inherited) conversion symptoms.

Stigmas and excessive affects are petite hystérie.

II (1930)

10.8.1930

Oral Eroticism in Education

1. It is not impossible that the question of how much oral eroticism (sucking the breast, the thumb, the dummy—kissing) should be allowed or even offered to the suckling, and later in the period of weaning, is of paramount importance for the development of character.

2. Tactless, un-understanding education provokes outbursts of rage and thus conditions the child to discharge tensions through aggressivity and destruction.

3. Simultaneously with these outbursts attempts at compensation develop: gratification by means of permitted parts of the body. (Screen memory: in the flat—the first remembered—sitting on the pot and rhythmically pushing a little toy (a tiny bell) up inside the nose. It remains stuck in the cavity of the nose, a doctor is called, attempts at escape. This screen memory emerged under the pressure of feelings of confusion and anxiety. The patient (woman) is essentially aggressive and negativistic. The relative friendliness of the analyst deprives her of the possibility of a fight; behind the aggressive tendencies anxiety becomes manifest, which then leads to the screen memory quoted above.) Obviously the love life of the newly born begins as complete passivity. Withdrawal of love leads to undeniable feelings of being deserted. The consequence is the splitting of the personality into two halves, one of which plays the role of the mother (thumb sucking: thumb is equalled with the mother’s breast). Prior to the splitting there is probably a tendency to self-destruction caused by the trauma, which tendency, however, can still be inhibited—so to speak—on its way: out of the chaos a kind of new order is created which is then adapted to the precarious external circumstances.

10.8.1930

Each Adaptation is preceded by an Inhibited Attempt at Splitting

1. Probably each living being reacts to stimuli of unpleasure with fragmentation and commencing dissolution (death-instinct?). Instead of ‘death-instint’ it would be better to choose a word that would express the absolute passivity of this process. Possibly complicated mechanisms (living beings) can only be preserved as units by the pressure of their environment. At an unfavourable change in the environment the mechanism falls to pieces and disintegrates as far (probably along lines of antecedent historic development), as the greater simplicity and consequent plasticity of the elements makes a new adaptation possible. Consequently autoplastic adaptation is always preceded by autotomy. The tendency to autotomy in the first instance tends to be complete. Yet an opposite movement (instinct of self-preservation, life-instinct) inhibits the disintegration and drives towards a new consolidation, as soon as this has been made possible by the plasticity developed in the course of fragmentation. It is very difficult to form a conception of the true essence of this instinctual factor and its function. It is as if it could command sources of knowledge and possibilities which go infinitely far beyond everything that we know as faculties of our conscious intelligence. It assesses the gravity of the damage, the amounts of energy of the environment and of the surrounding people, it seems to have some knowledge of events distant in space and to know exactly at what point to stop the self-destruction and to start the reconstruction. In the extreme case when all the reserve forces have been mobilized but have proved impotent in the face of the overpowering attack, it comes to an extreme fragmentation which could be called dematerialization. Observation of patients, who fly from their own sufferings and have become hypersensitive to all kinds of extraneous suffering, also coming from a great distance, still leave the question open whether even these extreme, quasi-pulverized, elements which have been reduced to mere psychic energies do not also contain tendencies for reconstruction of the ego.

10.8.1930

Autoplastic and Alloplastic Adaptation

Contrasted with the form of adaptation described above is alloplastic adaptation, i.e. the alteration of the environment in such a way as to make self-destruction and self-reconstruction unnecessary, and to enable the ego to maintain its existing equilibrium, i.e. its organization, unchanged. A necessary condition for this is a highly developed sense of reality.

10.8.1930

Autosymbolism and Historical Representation should be taken into consideration in equal measure when interpreting dreams or symptoms; the former hitherto much neglected. In hysterical symptoms a subjective moment of the trauma is essentially always repeated. First: the immediate sensory impressions; second: the emotions and the physical sensations associated with them; third: the accompanying mental states, which are represented also as such. (For instance: representation of unconsciousness by the feeling of the head being cut off or lost. Representation of confusion as vertigo, of distressing surprise as being caught in a whirlwind, and of the impotence of dying as being projected into a lifeless thing or animal. The splitting of the personality is mostly represented as being torn to pieces, the fragmentation as an explosion of the head.) Hysterical symptoms seem to be mere autosymbolisms, that is, reproductions of the ego memory-system, but without any connexion with the causative moments. One of the main methods of making something unconscious seems to be the accentuation of the purely subjective elements at the cost of knowledge about external causation.

10.8.1930

On the Analytical Construction of Mental Mechanisms

The topic-dynamic-economic construction of the mental apparatus is based exclusively on the elaboration of subjective data. We relate the sudden disappearance of one part of the content of the conscious, occurring simultaneously, seemingly without any motive, with the appearance of another idea, to a displacement of mental energy from one mental locality to another. A particular case of this displacement process is repression.

Certain observations urge us not to exclude out of hand the possibility of other processes in the mental apparatus. With the same right with which one speaks of the process of repression one may accept as valid statements by patients, that is to say, one may allow the topical point of view in cases in which the personality is described as torn into two or more parts and after this disintegration the fragments assume, as it were, the form and function of a whole person. (Analogy with zoological observation, according to which certain primitive animals can disintegrate and then the individual fragments can reconstitute themselves as whole individuals.) Another process requiring topical representation is characterized in the phrase ‘to get beside oneself’.1 The ego leaves the body, partly or wholly, usually through the head, and observes from outside, usually from above, the subsequent fate of the body, especially its suffering. (Images somewhat like this: bursting out through the head and observing the dead, impotently frustrated body, from the ceiling of the room; less frequently: carrying one’s own head under one’s arm with a connecting thread like the umbilical cord between the expelled ego components and the body.) Typical examples:

1. The ego suddenly acquires a widely extended vision and can move with ease in these endless plains. (Turning away from pain and turning towards external events.)

2. At a further increase of the painful tension: climbing the Eiffel Tower, running up a steep wall.

3. The traumatic force catches up and, as it were, shakes the ego down from the high tree or the tower. This is described as a frightening whirlwind, ending in the complete dissolution of connexions and a terrific vertigo, until finally

4. the ability, or even the attempt, to resist the force is given up as hopeless, and the function of self-preservation declares itself bankrupt. This final result may be described or represented as being partially dead.

In one case such ‘being dead’ was represented in dreams and associations as maximal pulverization, leading finally to complete de-materialization.

The de-materialized dead component has the tendency to drag the not yet dead parts to itself into non-existence, especially in dreams (particularly in nightmares).

It is not impossible that, by further accumulation of experience, the topical point of view will be able to describe, in addition to displacement and repression, also the fragmentation and pulverization of complex mental structures.

17.8.1930

On the Theme of Neo-catharsis

It appears that we must make an exact differentiation between that part of catharsis which appears spontaneously when approaching the pathogenic mental content and that which, as it were, can only be elicited by overcoming strong resistance. The single cathartic outbreak is not essentially different from the spontaneous hysterical outbreak with which patients ease their tensions from time to time. In neo-catharsis such an outbreak indicates merely the place where further detailed exploration has to begin, that is to say, one must not content oneself with what is given spontaneously, which is somehow adulterated, partially displaced, and quite often attenuated; one must press on (of course as far as possible without suggesting contents) to obtain from the patient more about his experiences, the accompanying circumstances, and so on. After the ‘waking up’ from this trance state, the patient feels more stable for a time; that state is soon dissipated, however, and gives way to feelings of insecurity and doubt, which often deteriorate into hopelessness. ‘Well, all this sounds all right’, they say frequently—‘but is it also true? I shall never, never find security based on true recollections.’ The next time the cathartic work sets in at quite a different place, and leads, not without energetic pressure from ourselves, to the repetition of other traumatic scenes. This hard task must be repeated innumerable times until the patient feels, as it were, surrounded, and cannot but repeat before our eyes the trauma which originally had led to mental disintegration. (It is as if one had, by strenuous mining operations, to open a cave filled with gas under high pressure. The earlier, smaller outbreaks were like cracks from which some of the material could escape, but which soon closed up spontaneously.) In the case of Tf. the cathartic work lasted longer than a year, after a preceding analysis of four years, it is true with some interruptions. It must be admitted, however, that my lack of knowledge of the neocathartic possibilities may be responsible for the long duration of the analysis.

24.8.1930

Thoughts on ‘Pleasure in Passivity’

The problem of bearing, accepting, even enjoying unpleasure seems to be insoluble without far-reaching speculations. The assertion and defence of egoistic interests is certainly a well-tried form of securing an unendangered tranquillity. At the moment when all defensive forces have been exhausted (but also, when the suddenness of aggression overpowers the defensive cathexes), the libido apparently turns against the self with the same vehemence with which it has defended it till then. Indeed, one could speak of identification with the stronger victorious opponent (on the other hand the role of the opponent can be taken also by some unspecified, impersonal elemental forces). The fact is that such self-destruction can be associated with feelings of pleasure and it is necessarily so associated in cases of masochistic surrender. Whence this pleasure? Is it only (as I ventured to interpret it earlier) the identification in fantasy with the destroyer—or have we rather to suppose that the enjoyment of the egoistic tranquillity—after the recognition that it cannot be preserved any longer and that a new form of equilibrium has become necessary—veers suddenly round to a pleasure in self-sacrifice, which could confidently be called ‘altruistic pleasure’? The example of the bird, fascinated by the sight of a serpent or by the claws of the eagle, which, after a short period of resistance, throws itself to its own ruin, can be quoted here. In the moment when one must cease to use the environment as material for one’s own security and well-being (i.e. when the environment does not consent any longer to accept the role of being incorporated in this way), one accepts the role of sacrifice, so to speak, with sensual pleasure, i.e. the role of material for other, stronger, more self-asserting, more egotistic, forces. Egotistic and altruistic tranquillity were, accordingly, only the two extremes of a higher general principle of tranquillity, including both. The instinct of tranquillity is accordingly the principal instinct, to which the life (egotistic) and death (altruistic) instincts are subjected.

The change of direction of the libido does not always happen in this sudden way nor is it always complete. One could say that the pleasure in self-destruction often (but not always) goes no further than it is driven by the irresistible forces. As soon as the rage of the elements (or of the human environment, most frequently of the parents and adults) has exhausted itself, the part of the ego which remained intact immediately starts to build up a new personality from the preserved fragments, a personality which, however, bears the traces of the endured struggle fraught with defeat. This new personality is called one that is ‘adjusted to the conditions’. Each adaptation is accordingly a process of destruction interrupted in its course. In some cases of fragmentation and atomization after a shock the pleasure in one’s own defeat was expressed in:

I have the feeling that with these points the motivation of the pleasure of self-destruction is far from being exhausted and would like to add that partial destruction (immediately after a trauma or shock)—as represented in fantasies and dreams—shows the previously unified personality in a secondarily narcissistic splitting, the ‘dead’, ‘murdered’ part of the person—like a child—nursed, wrapped up in, by the parts which remained intact. In one of my cases it came, in later years, to a repeated trauma which, for the most part, destroyed also this nursing outer shell (atomization). Out of this as it were pulverized mass there developed a superficial, visible, even partly conscious, personality, behind which the analysis was able to reveal not only the existence of all previous layers, but was also able to revive these layers. In this way it was possible to dissolve quite ossified character traits, products of adaptation, forms of reaction, and to reawaken stages apparently long superseded.

Behind this ‘pleasure of adaptation’ or ‘altruistic pleasure’ it was possible to reveal the defeated egotistic pleasure. To be sure, this pleasure had first to be strengthened by the force of analytic encouragement. With our help the analysand is able to face, to bear, even to react to, situations which formerly were too much for him in his state of isolation and helplessness to which he had had to surrender unconditionally, even surrender with pleasure. Far-going homosexual bondages can occasionally be traced back to their traumatic sources and the adaptive reaction be re-transformed into a reactive one.

Expressed in biological terms this means: Re-activation of the traumatic conflicts and dealing with them in an alloplastic way instead of the previous autoplastic one.

31.8.1930

Fundamental Traumatic Effect of Maternal Hatred or of the Lack of Affection

T.Z. speaks incessantly of hate waves which she has always felt as coming from her mother, according to her fantasy even when still in mother’s womb. Later she felt unloved because she was born a girl and not a boy. Identical conditions in Dm. and B.

Dm. has always had the compulsion to seduce men and to be thrown into disaster by them. In fact she has done so only to escape from the loneliness which was brought upon her by her mother’s coldness. Even in the overpassionate ruthless expressions of love by her mother, she felt her mother’s hatred as a disturbing element (difficult birth, although no actual contraction of the pelvis).

S. had to be brought up by the father because of his mother’s aggressiveness. The father died when the child was eighteen months old and then he was delivered over to the cruelty of the mother and the grandfather. These traumata have led to disturbance of all object relations. Secondary narcissism.

The relation between the strong heterosexual trauma (father) and the defective mother fixation must remain problematic for the time being. Further experience needed.

7.9.1930

Fantasies on a Biological Model of Super-ego Formation

H.’s spontaneous statement on her fatness: ‘all this fat is my mother’. If she felt freer inside from the disastrous (introjected) mother-model, then she noticed a decrease in the fat padding, and at the same time she lost weight.

During the week, in which, for the first time, he faced up defensively to his cruel mother: S. felt he had lost weight. At the same time, however, he had the idea that this fat was that of his equally cruel grandfather.

These observations lead to the idea that formation of the super-ego occurs as the final outcome of a fight, in reality lost, with an overwhelming (personal or material) force, roughly in the following way:

A precondition is the existence of an ‘intelligence’ or a ‘tendency to deal with things economically’, with an exact knowledge of all the qualitative and quantitative energy charges and possibilities of the body, also of the ability of the mind to accomplish, to bear, and to tolerate; in the same way this ‘intelligence’ can estimate with mathematical exactitude the distribution of power in the external world. The first normal reaction of a living being to external unpleasure is an automatic warding off, that is to say a tendency to self-preservation. If beaten down by an overwhelming force, the energy (perhaps in fact the external power of the trauma) turns against the self. In this moment the ‘intelligence’, which is concerned above all with the preservation of the united personality, seems to resort to the subterfuge of turning round the idea of being devoured in this way: with a colossal effort the ‘intelligence’ swallows the whole hostile power or person and imagines1 that it itself has devoured somebody else and, in addition, its own person. In this way man can have pleasure in his own dismemberment. Now, however, his personality consists of a devoured, over-great (fat) aggressor and a much smaller, weaker person, oppressed and dominated by the aggressor, that is, his pre-traumatic personality. Many neurotics symbolize their illness in dreams and symptons as a bundle that they have to carry on their backs; in others this bundle becomes part of the body and turns into a hump or growth; also favoured is the comparison with an enveloping great person which, as it were, enwraps maternally the former personality.

The psychological ‘devouring’ seems to be associated with greedy voracity and increased hunger for assimilation: putting on fat as a hyserictal symptom. If, by the analytic revision of the traumatic struggle, the person has been freed from the overwhelming power, then the obesity, the physiological parallel phenomenon, may disappear.

Physiological and chemical aspects: the muscle and nerve tissues consist, in essence, of protoplasm, that is to say mainly of proteins. Protein is specific for each species, perhaps even for each individual. Foreign protein acts as poison; it is therefore broken down and the specific protein synthesized anew out of the harmless constituents. Not so with unspecific fat. Pork fat, for instance, is stored in the cells as such, and can quite well stand as the organic symbol, or the organic tendency to manifestation, which runs parallel with the devouring of the external powers.

Here a still quite vague idea emerges. Is it possible that the formation of the super-ego and the devouring of the superior force in defeat may explain the two following processes:

(1) ‘Eating up the ancestors’, and (2) adaptation in general.

1. Plants grow and develop through the incorporation of minerals. Thereby the possibility of existence within the organism is offered to minerals (inorganic substances) which, however, is equivalent to being devoured by the organism. How far the inorganic matter as such is destroyed or dissolved, however, remains problematic. Quantitative analysis rediscovers the consumed inorganic substances to the last grain. When the plant is devoured by a herbivorous animal, the plant organism is destroyed, that is to say reduced to organic or even partly inorganic components. It remains problematic whether or not, despite this, part of the plant substance survives and conserves its individuality, even in the body of the herbivorous animal. In this way the animal body is a superstructure of organic and inorganic elements. Expressed psycho-analytically (although at first glance highly paradoxical) this means: the animal organism has devoured one part of the (menacing?) external world and thus provided for the continuation of its own existence.

The same thing happens at the devouring of animal organisms. It is possible that we harbour in our organism inorganic, vegetative, herbivorous, and carnivorous tendencies like chemical valencies. The likewise highly paradoxical aphorism here is as follows: ‘Being devoured is, after all, also a form of existence.’

The idea then emerges that one ought to consider in this process the possibility of a mutual devouring, that is to say a mutual super-ego formation.

2. Adaptation in general appears to be a mutual devouring and being devoured, whereby each party believes that he has remained the victor.

21.9.1930

Trauma and Striving for Health

The immediate effect of a trauma which cannot be dealt with at once is fragmentation. Query: is this fragmentation merely a mechanical consequence of the shock? or is it as such already one form of defence, i.e. adaptation? Analogy with the falling to pieces of lower animals when subjected to excessive stimulation and continuation of existence in fragments. (To be looked up in biological text books.) Fragmentation may be advantageous (a) by creating a more extended surface towards the external world, i.e. by the possibility of an increased discharge of affects; (b) from the physiological angle: the giving up of concentration, of unified perception, at least puts an end to the simultaneous suffering of multiple pain. The single fragments suffer for themselves; the unbearable unification of all pain qualities and quantities does not take place; (c) the absence of higher integration, the cessation of the interrelation of pain fragments allows the single fragments a much greater adaptability. Example: at a loss of consciousness, changes in the shape of the body (being stretched, strained, bent, compressed to the limit of physical elasticity) appear to be possible, whereas a simultaneous defence reaction would increase the danger of irreparable fractures or tears, of. examples of terrible injuries in childhood, for instance violation, with ensuing shock and rapid recovery.

By the shock, energies which have hitherto been quiescent or used up in object relations are suddenly awakened in the form of narcissistic care, concern, and helpfulness. The certainly quite unconscious internal force, as yet unrecognized in its essence, which estimates with mathematical accuracy both the severity of the trauma and the available ability for defence, produces with automatic certainty and according to the pattern of a complicated calculating machine the only practical and correct psychological and physical behaviour in a given situation. The absence of emotions and speculations which might disturb the senses and distort reality permits the exact functioning of the calculating machine, as if in sleep-walking.

As soon as the shock has, in a way, been dealt with by means of the above processes, the psyche hastens to concentrate in a unit the individual fragments which have now once more become manageable. Consciousness returns, but is completely unaware of the processes since the trauma.

It is much more difficult to explain the symptom of retroactive amnesia. Probably it is a defensive mechanism against the memory of the trauma itself.

Further examples of the regenerative tendency to be worked out in detail.

III (1931)

9.3.1931

Attempt at a Summary

1. Technical. Further development of neocatharsis: contrary to the conception previously current, according to which pathogenic material must be probed only associatively so that it may discharge and emotionally empty itself spontaneously and, because of its strong tension, with great vehemence (and at the same time creating and leaving behind it the feeling of the reality of having experienced a trauma), there occurs, to one’s astonishment, soon and occasionally immediately after each such discharge a revival of the doubts about the reality of all that has been experienced in the trance state. In some cases the feeling of well-being lasts the whole day, yet nightly sleep and dreaming, especially the awakening from them, bring a complete reappearance of the symptoms, complete loss of the confidence of the previous day, even once more the feeling of complete hopelessness. There may then follow days, even weeks, of complete resistance; until the next successful absorption in the deepest layers of the spheres of experience reaches the same moment of experience, complements it with new convincing details, and brings a renewed strengthening of the reality feeling with somewhat more permanent effect.

Absorption in the real sphere of emotional experience inevitably demands as complete as possible an abandonment of present reality. In principle so-called free association is in itself such a diversion of attention from actual reality, yet this diversion is rather superficial and is maintained at a rather conscious, at the most pre-conscious, level both by the intellectual activity of the patient and by our attempts to explain and interpret following one on the other in more or less rapid succession. It indeed requires of the patients a colossal trust to allow such absorption in the presence of another person. They must first have the feeling that, even in our presence (a) they can allow themselves everything in words, gestures, emotional outbreaks, without fear of punishment or of being pulled up by us in any way; and more than that [they can expect]1 complete sympathy and full understanding of everything, come what may. It is in addition a precondition that they should safely feel that we mean well and are willing to help, and that they must also have the hope that we are indeed able to help. (b) No less important is the feeling of reassurance that we are sufficiently powerful to protect the patient against all excesses which might be harmful to him, to us, to other persons and things, and especially that we are both willing and able to bring him back from this ‘mad unreality’. Some secure our goodwill in a truly childish fashion by clutching our hand or holding it fast during the whole period of the absorption in the trance. What one calls trance is, therefore, a kind of state of sleep in which communication is yet kept up with a reliable person. Slight changes in the force of the grip here become the means of expressing emotions. Responding or not responding to the changing pressure of the grip may then be taken as the measure and direction of the analyst’s reaction. (In an emergency, for instance in the case of too great anxiety, a firm pressure can prevent a frightened awakening; the limpness of our hand is occasionally felt and evaluated as a mute contradiction or as a partial dissatisfaction with the material.)

ESCAPE OF THE PATIENT FROM CONTACT WITH THE ANALYST

After this communication with the patient has lasted for a more or less longish time, just like a conversation in half-sleep, which has to be guided with extraordinary tact and the greatest possible economy and adaptation, it may happen that the patient is suddenly overpowered by an extremely strong hysterical pain or spasm, not infrequently by a true hallucinatory nightmare, in which he acts out in word and gesture some inner or external experience. There is always present the tendency to awake immediately afterwards, to look round for some seconds as if dazed, and then to reject all that has happened as a stupid and senseless fantasy. With some skill we can succeed, however, in restoring contact with the patient who is still in the fit. This must be done rather forcefully. Without actually giving him direct hints, the patient can be brought to tell us about the causes of his pain, the meaning of his defensive struggle, still apparent in his muscles. We may thus succeed in getting from him details of his emotional and sensory processes and of the exogenic causes of those traumas and sensations, and the defences against them. Often the responses at first appear very indistinct and vague. After some urging, however, an enveloping cloud, a weight pressing heavily on the chest, may gradually assume definite outlines; there may then be added to it the taut features of a man which, according to the patient’s feelings, express hatred or aggressiveness; the indistinct sensations of pain and congestion in the head may reveal themselves as remote consequences of a sexual (genital) trauma; when we then put all these formulations to the patient and urge him to combine them into a whole, we may experience the re-emergence of a traumatic scene with distinct indications of the time and place at which it occurred. Not infrequently we then succeed in differentiating the autosymbolic representation of the mental processes after the trauma (e.g. fragmentation as falling to bits, atomization as explosion) from the real external traumatic events, and in this way reconstruct the total picture of both the subjective and objective history. There often follows, then, a state of calm relaxation, with a feeling of relief. It is as if the patient had with our help succeeded in climbing a hitherto unscaleable wall which awakes in him a feeling of increased internal power, with the help of which he has now succeeded in conquering certain dark forces whose victim he had been until now. However, as already mentioned, we should not place too much hope on the permanence of this success; the next day we may find the patient in full rebellion and desolation again, and often it is only after some days’ effort that we may succeed in getting near once more to the painful point, or in getting out of the depths new painful points which are interwoven with the previous ones as it were in a traumatic web.

Budapest, 13.3.1931

On the Patient’s Initiative

To continue the previous paper on the humility of the analyst: this could be extended also to the way of keeping the work going. In general it is advantageous: to consider for a time every one, even the most improbable, of the communications as in some way possible, even to accept an apparently obvious delusion. Two reasons for this: thus, by leaving on one side the ‘reality’ question, one can feel one’s way more completely into the patient’s mental life. (Here something should be said about the disadvantages of contrasting ‘reality’ and ‘unreality’. The latter must in any case be taken equally seriously as a psychic reality; hence above all one must become fully absorbed in all that the patient says and feels. Connexions here with metaphysical possibilities.) As a professional man the physician feels uneasy, of course, when the patient not only expresses his own opinion of the interpretations, which opinion is in complete contradiction to the current (analytic) convictions, but also criticizes the methods and techniques used by the physician, ridicules them for their inefficiency, and puts forward his own technical propositions. There are two motives which might lead one to change the usual technique in some way, even in the sense of the patient’s propositions: (1) if one has not made progress with work lasting weeks, months, or even years, and the analyst is faced with the possibility of dropping the case as incurable. It is indeed more logical, before giving it up completely to try out on the case some of the patient’s propositions. Of course therapeutically this has always been so, only the physician had to know that what he then did was no longer analysis, but something different. I would like to add, however, that the occasional accepting of ‘something different’ may enrich even the analysis itself. Analytical technique has never been, nor is it now, something finally settled; for about a decade it was mixed with hypnosis and suggestion … [Continuation not found. Editor.]

22.3.1931

Relaxation and Education

It appears that patients arrive at a point—even if granted the greatest toleration and freedom for relaxing—where the freedom must be somewhat restricted out of practical considerations: e.g. the desire to have the analyst constantly present, the desire to change the transference situation into a real lasting relation, must remain unfulfilled. The consequent, often extraordinarily strong emotional reaction repeats the shock which led originally to symptom formation. The analyst’s great compliance and acquiescence bring for a while—as if by contrast—many bad, hitherto unconscious, experiences of the infantile period into consciousness or make reconstruction feasible. Finally it becomes possible to reduce—so to speak—the whole pathological fabric to the traumatic core and then almost all dream analyses become centred around a few staggering infantile experiences. Occasionally during such analyses the patients are carried away by their emotions; states of severe pain both mental and physical, deliria with more or less deep loss of consciousness, and coma mix themselves into the work of pure intellectual associations and constructions. One urges the patient in this state to give information about the causes of the various emotional and perceptual disturbances. The insight achieved in this way brings about a kind of gratification which simultaneously is emotional and intellectual and is worthy to be called a conviction. But this gratification does not last long, often for some hours only; the next night brings the distorted repetition of the trauma perhaps in the form of a nightmare, without the slightest feeling of understanding; the whole conviction has completely gone. The transitory, intellectual and emotional conviction is torn to bits again and again and the patient oscillates, now as before, between the symptom in which he feels all the unpleasure and does not understand anything, and the conscious reconstruction in which he understands everything yet feels little or nothing. A deep change of this often tiresome and automatic oscillation is brought about by the need mentioned above to restrict the relaxation. It is the high degree of our compliance that makes even the slightest refusal by us uncommonly painful; the patient feels as if he were struck off his balance, produces the most intense degrees of shock and resistance, he feels deceived but inhibited in his aggressiveness, and ends in a kind of paralysed state which he experiences as dying or being dead. If we then succeed in directing this state away from us and back to the infantile traumatic events, it may happen that the patient seizes the moment in which, at that time, knowing and feeling led, under the same symptoms of helpless rage, to self-destruction, to splitting of the mind in unconscious feeling and unfelt knowing,1 i.e. to the same process that Freud assumes to be the basis of repression. Our analyses will and apparently can go back also to these preliminary stages of the process of repression. It is true that to achieve this one must give up completely all relation to the present and sink completely into the traumatic past. The only bridge between the real world and the patient in this state of trance is the person of the analyst, who, instead of the simple gesticulatory and emotional repetition, urges the patient struggling with his affects to intellectual work, encouraging him incessantly with questions.

A surprising but apparently generally valid ct fain this process of self-splitting is the sudden change of the object-relation that has become intolerable, into narcissism. The man abandoned by all gods escapes completely from reality and creates for himself another world in which he, unimpeded by earthly gravity, can achieve everything that he wants. Has he been unloved, even tormented, he now splits off from himself a part which in the form of a helpful, loving, often motherly, minder commiserates with the tormented remainder of the self, nurses him and decides for him; and all this is done with deepest wisdom and most penetrating intelligence. He is intelligence and kindness itself, so to speak a guardian angel. This angel sees the suffering or murdered child from the outside (consequently he must have, as it were, escaped out of the person in the process of ‘bursting’), he wanders through the whole Universe seeking help, invents fantasies for the child that cannot be saved in any other way, etc. But in the moment of a very strong, repeated trauma even this guardian angel must confess his own helplessness and well meaning deceptive swindles to the tortured child and then nothing else remains but suicide, unless at the last moment some favourable change in the reality occurs. This favourable event to which we can point against the suicidal impulse is the fact that in this new traumatic struggle the patient is no longer alone. Although we cannot offer him everything which he as a child should have had, the mere fact that we can or may be helpful to him gives the necessary impetus towards a new life in which the pages of the irretrievable are closed and where the first step will be made towards acquiescence in what life yet can offer instead of throwing away what may still be put to good use.

26.3.1931

On the Revision of the Interpretation of Dreams

In Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams the wish-fulfilling transformation of the disturbing unpleasurable residues of the day is represented as the sole function of the dream. The importance of these day’s and life’s residues is elucidated with almost unsurpassable accuracy and clarity; I think, however, that the recurrence of the clay’s residues in itself is one of the functions of the dream. While following up the connexions, it strikes us more and more that the so-called day’s (and as we may add, life’s) residues are indeed repetition symptoms of traumata. As is known the repetition tendency fulfils in itself a useful function in the traumatic neuroses; it endeavours to bring about a better (and if possible a final) solution than was possible at the time of the original shock. This tendency is to be assumed even where no solution results, i.e. where the repetition does not lead to a better result than in the original trauma. Thus instead of ‘the dream is a wish-fulfilment’ a more complete definition of the dream function would be: every dream, even an unpleasurable one, is an attempt at a better mastery and settling of traumatic experiences, so to speak, in the sense of an esprit d’escalier which is made easier in most dreams because of the diminution of the critical faculty and the predominance of the pleasure principle.

I would like the return of the day’s and life’s residues in the dream not to be considered as mechanical products of the repetition instinct but to presume that behind it is the functioning of a tendency (which should be called psychological) towards a new and better settlement, and the wish-fulfilment is the means which enables the dream to achieve this aim more or less successfully. Anxiety dreams and nightmares are neither wholly successful nor even almost entirely unsuccessful wish-fulfilments, but the beginnings of this are recognizable in the partially achieved displacement. Day’s and life’s residues are accordingly mental impressions, liable to be repeated, undischarged and unmastered; they are unconscious and perhaps have never been conscious; these impressions push forward more easily in the state of sleep and dreaming than in a waking state, and make use of the wish-fulfilling faculty of the dream.

In a case, observed for many years, each night brought two and often several dreams. The first dream, experienced in the hours of the deepest sleep, had no psychic content; the patient awoke from it with a feeling of great excitement with vague recollections of pain, of having experienced both physical and mental sufferings and with some indications of sensations in various organs of the body. After a period of remaining awake she fell asleep with new, very vivid dream images which turned out to be distortions and attenuations of the events experienced in the first dream (but even there almost unconsciously). Gradually it became clear that the patient could and must repeat the traumatic events of her life, purely emotionally and without any ideational contents, only in a deep unconscious, almost comatose sleep; in the subsequent less deep sleep, however, she could bear only wish-fulfilling attenuations. Theoretically important in these and similar other observations is the relation between the depth of the unconsciousness and the trauma, and this justifies the experiments of searching for the experiences of shock in an intentionally induced absorption in trance. An unexpected, unprepared for, overwhelming shock acts like, as if it were, an anaesthetic. How can this be? Apparently by inhibiting every kind of mental activity and thereby provoking a state of complete passivity devoid of any resistance. The absolute paralysis of motility includes also the inhibition of perception and (with it) of thinking. The shutting off of perception results in the complete defencelessness of the ego. An impression which is not perceived cannot be warded off. The results of this complete paralysis are: (1) The course of sensory paralysis becomes and remains permanently interrupted; (2) while the sensory paralysis lasts every mechanical and mental impression is taken up without any resistance; (3) no memory traces of such impressions remain, even in the unconscious, and thus the causes of the trauma cannot be recalled from memory traces. If, in spite of it, one wants to reach them, which logically appears to be almost impossible, then one must repeat the trauma itself and under more favourable conditions one must bring it for the first time to perception and to motor discharge.

Returning to the trauma: the state of unconsciousness, the state of sleep, favours not only the dominance of the pleasure principle (wish-fulfilling function of the dream), but also the return of unmastered traumatic sensory impressions which struggle for solution (traumatolytic function of the dream). In other words: the repetition tendency of the trauma is greater in sleep than in waking life; consequently in deep sleep it is more likely that deeply hidden, very urgent sensory impressions will return which in the first instance caused deep unconsciousness and thus remained permanently unsolved. If we succeed in combining this complete passivity with the feeling of ability to re-live the trauma (i.e. to encourage the patient to repeat and to live it out to the end—which often only succeeds after innumerable unsuccessful attempts and at first usually only piecemeal) then it may come to a new, more favourable and possibly lasting mastery of the trauma. The sleep itself is unable to achieve this—at most it can lead only to a new repetition with the same paralysing end result. Or it may happen that the sleeper wakes with the feeling of having experienced various mental and physical unpleasurable sensations, then falls asleep again and in his dream the distorted mental contents appear. The first dream is purely repetition; the second an attempt at settling it somehow by oneself, i.e. with the help of attenuations and distortions, consequently in a counterfeited form. Under the condition of an optimistic counterfeit the trauma may be admitted to consciousness.

The main condition of such a counterfeit seems to be the so-called ‘narcissistic split’, i.e. the creation of a censuring instance (Freud) out of a split off part of the ego which, as it were, as pure intellect and omniscience, with a Janus head estimates both the extent of the damage and that part of it which the ego can bear, and admits to perception only as much of the form and content of the trauma as is bearable, and if necessary, even palliates it by a wish-fulfilment.

An example of this type of dream: Patient to whom the father made advances on several occasions in childhood and also when she reached adult age, for many months brings material that indicates a sexual trauma in her fifth year; yet despite innumerable repetitions in fantasy and in half-dream, this trauma could not be recollected, nor could it be raised to the level of conviction. Many times she wakes up from the first deep sleep ‘as if crushed’ with violent pains in her abdomen, feeling of congestion in her head, and all ‘muscle-wrenched as if after a violent struggle’, with paralysing exhaustion, etc. In the second dream she sees herself pursued by wild animals, being thrown to the ground, attacked by robbers, etc. Minor details of the persecutor point to the father, his enormous size to childhood. I regard the ‘primary dream’ as the traumatic-neurotic repetition, the ‘secondary dream’ as the partial settlement of it without external help by means of narcissistic splitting. Such a secondary dream had roughly this content: a small cart is pulled uphill by a long row of horses along a ridge so to speak playfully. To right and left are precipices; the horses are driven in a certain kind of rhythm. The strength of the horses is not in proportion to the easiness of the task. Strong feelings of pleasure. Sudden change of the scene: a young girl (child?) lies at the bottom of a boat white and almost dead. Above her a huge man oppressing her with his face. Behind them in the boat a second man is standing, somebody well known to her, and the girl is ashamed that this man witnesses the event. The boat is surrounded by enormously high, steep mountains so that nobody can see them from any direction except perhaps from an aeroplane at an enormous distance.

The first part of the secondary dream corresponds to a scene partly well known to us, partly reconstructed from other dream material, in which the patient as a child slides upwards astride the body of her father and with childish curiosity makes all sorts of discovery trips in search of hidden parts of his body, during which both of them enjoy themselves immensely. The scene on the deep lake reproduces the sight of the man unable to control himself, and the thought of what people would say if they knew; finally the feeling of utter helplessness and of being dead. Simultaneously in an autosymbolic way: the depth of unconsciousness, which makes the events inaccessible from all directions, at the most perhaps God in heaven could see the happenings, or an airman flying very very far away, i.e. emotionally uninterested. Moreover, the mechanism of projection as the result of the narcissistic split is also represented in the displacement of the events from herself on to ‘a girl’.

The therapeutic aim of the dream analysis is the restoration of direct accessibility to the sensory impressions with the help of a deep trance which regresses, as it were, behind the secondary dream, and brings about the re-living of the events of the trauma in the analysis. Consequently after the normal dream analysis in a waking state there followed a second analysis in trance. In this trance one endeavours to remain in touch with the patient which demands much tact. If the expectations of the patients are not satisfied completely they awake cross or explain to us what we ought to have said or done. The analyst must swallow a good deal and he must learn to renounce his authority as an omniscient being. This second analysis frequently makes use of some images of the dream in order to proceed through them, as it were, into the dimension of depth, i.e. into reality.

After the trance and before the waking up it is advisable to sum up what has been lived through into one total experience and then present it to the patient. After this then follows the process of waking up which demands special precautions, e.g. it is useful after the waking up to talk over again what has happened in the session. (Here one could possibly insert the train of thought about the difference between ‘suggestion of content’ in the earlier hypnoses and the pure suggestion of courage in the neo-catharsis: the encouragement to feel and to think the traumatically interrupted mental experiences to their very end.)

2.4.1931

Aphoristic Remarks on the Theme of being Dead—being a Woman

Continuing the train of thought about adaptation—each adaptation is a partial death, a surrender of one part of the personality; condition: traumatically disorganized mental substance from which then an external power may take away some pieces or into which it may add foreign elements—we must arrive at the question whether the problem of the theory of genitality—the genesis of the differences of sexes—should not be regarded also as a phenomenon of adaptation, i.e. of partial death? If this is so, it is perhaps not impossible that the higher intellectual faculties which I assumed to exist in woman might be explained by her having experienced a trauma. In fact a paraphrase of the old adage: the wiser one gives in. Or more correctly: he (she) who gives in becomes wiser. Or better still: the person struck by a trauma comes into contact with death, i.e. with the state in which egotistic tendencies and defensive measures are shut off, above all resistance by friction, which in the egotistic form of existence brings about the isolation of objects and the self in time and space. In the moment of the trauma some sort of omniscience about the world associated with a correct estimation of the proportions of the own and foreign powers and a shutting out of any falsification by emotivity (i.e. pure objectivity, pure intelligence), makes the person in question—even after consequent consolidation—more or less clairvoyant. This could be the source of feminine intuition. A further condition is naturally the supposition that the instant of dying—if perhaps after a hard struggle the inevitability of death has been recognized and accepted—is associated with that timeless and spaceless omniscience.

But now here is again the confounded problem of masochism! Whence the faculty, to become not only objective and, as far as is necessary, to renounce or even to die, but also to obtain pleasure out of this destruction? (i.e. not only acceptance of unpleasure but also addiction to unpleasure).

1. The voluntary searching for, or even hastening of, the unpleasure has subjective advantages vis-à-vis what may be a prolonged expectation of unpleasure and death. Above all it is I alone who prescribe for myself the tempo of living and dying; the motive of anxiety about something unknown is shut out. Compared with the expectation of death coming from outside, suicide is relative pleasure.

2. The voluntary hastening in itself (the flight of the little bird towards the claws of the bird of prey, in order to die more quickly) must mean some sort of gratifying experience.

3. There is a good deal in favour of associating such kind of voluntary surrender with compensatory hallucinations (deliria of rapture; displacement of unpleasure on to others, mostly on to the aggressor himself; fantastic identification with the aggressor; objective admiration of the power of the forces attacking the self; and lastly the finding of ways and means of real hope of possible vengeance and superiority of another kind even after defeat).

9.4.1931

The Birth of the Intellect

Aphoristically expressed: intellect is born exclusively of suffering. (Commonplace: one is made wise by bad experiences; reference to the development of memory from the mental scar-tissue created by bad experiences. Freud.)

Paradoxical contrast; intellect is born not simply of common, but only of traumatic, suffering. It develops as a consequence of, or as an attempt at, compensation for complete mental paralysis (complete cessation of every conscious motor innervation, of every thought process, amounting even to an interruption of the perception processes, associated with an accumulation of sensory excitations without possibility of discharge). What is thereby created deserves the name of unconscious feeling. The cessation or destruction of conscious mental and physical perceptions, of defensive and protective processes, i.e. a partial dying, seems to be the moment at which, from apparently unknown sources and without any collaboration from consciousness, there emerge almost perfect intellectual achievements; such as most exact assessment of all given external factors, and grasping of the only correct or only remaining possibilities, fullest consideration of one’s own and others’ psychological possibilities, both in their qualitative and quantitative aspects. Brief examples:

1. Sexual aggression of intolerable intensity against small children: unconsciousness; awakening from the traumatic shock without memory but with changed character: in boys, effeminization, in girls, the same or the exact opposite, ‘masculine protest’. It is to be called intelligent when the individual, while still unconscious or comatose, assessing correctly the proportion of powers, chooses the only way of saving life, that is, giving in completely; it is true at the price of more or less mechanized, permanent change and the partial loss of mental elasticity.

2. Succeeding in achieving an almost impossible acrobatic performance, such as jumping down from the fourth floor, and, during the fall, jumping into the corridor of the third.

3. Sudden awakening from a traumatic-hypnotic sleep lasting more than ten years, immediate comprehension of the hitherto almost or completely unconscious past, immediate assessment of the deadly aggression to be expected with absolute certainty, decision of suicide, and all that in one and the same moment.

Here we are faced with intellectual super-performances, which are inconceivable psychologically and which demand metaphysical explanation. At the moment of transition from the state of life into that of death there arrives an assessment of the present forces of life and the hostile powers, which assessment ends in partial or total defeat, in resignation, that is to say, in giving oneself up. This may be the moment in which one is ‘half dead’, i.e. one part of the personality possesses insensitive energy, bereft of any egoism, that is, an unperturbed intelligence which is not restricted by any chronological or spatial resistances in its relation to the environment; the other part, however, still strives to maintain and defend the ego-boundary. This is what has been called in other instances narcissistic self-splitting. In the absence of any external help one part of this split-off, dead, energy, which possesses all the advantages of the insensibility of lifeless matter, is put at the service of preservation of life. (Analogy with the development of new living beings after mechanical disturbance or destruction which turns into productivity, as, for instance, Loeb’s experiments in fertilization; sec the relevant chapter in my Theory of Genitality.1 The only ‘real’ is emotion=unscrupulous acting or reacting, i.e. what one otherwise calls mad.)

Pure intelligence is thus a product of dying, or at least of becoming mentally insensitive, and is therefore in principle madness, the symptoms of which can be made use of for practical purposes.

30.7.1931

Fluctuation of Resistance

(Patient B)

Sudden interruption of a fairly long period of productive and reproductive fertile work (scenes, almost physically experienced in the sessions, of seduction and overpowering by the father at the age of 4(?) years), then the sudden emergence of a practically insurmountable resistance. In any case the preceding sessions and also the intervening period were filled with almost unbearable feelings and sensations: as if the back were being broken in two; an enormous weight obstructing breathing which, after a transitory aphonia and nearly suffocating congestion in the head, was suddenly replaced by breathlessness, deadly pallor, general paralytic weakness and loss of consciousness. The crisis of these symptoms of repetition was represented by: (1) a dream of hallucinatory reality in which a thin, long rubber tube penetrates the vagina, is pushed up to the mouth and is then withdrawn, thus producing at each repeated penetration rhythmic feelings of suffocation; (2) a marked swelling of the abdomen: imagined pregnancy becoming more and more enormous, painful, and menacing. One morning the patient appeared suddenly without pains, unproductive in every respect but without symptoms; my good-humoured question whether her pregnancy had been terminated by abortion was followed by obstinacy and a feeling of being offended, which lasted for weeks. Everything achieved up till then lost its value. Patient full of doubts, hopeless, impatient. I show her consistently the tendency to escape. All in vain; with strong logical consistency she marshals her motives for being justifiably in despair over both her analysis and her whole future; often she sharply criticizes the behaviour of analysts and patients whom she knows and who are partly tied up with me. But, as she is unable to admit of any other solution than psycho-analysis, her whole endeavour and pondering comes to nothing except a general pessimism with hints of suicide.

To-day, after I had shown her that her accusations and despair were really only a disguise for her idea of interrupting the analysis, she spoke, among other things, of her inability to stop thinking and instead of it to uncover her unconscious with the help of really free association. I urged her somewhat energetically to produce free fantasies, and she immediately became absorbed in the unpleasurable sensation of the pain in her back (as if broken). After further urging, she located these sensations again in her birthplace; further she associated them with lying in grass, then the feeling: something horrible had happened to her (by whom?). ‘I don’t know, perhaps my father.’

In any case, my energetic urging to free associations, and simultaneous making her aware of my sincere sympathy, succeeded in breaking through the resistance.

Similar fluctuations, with the same suddenness, happened previously. What do they mean? Are they (1) simply attempts to escape from pain which is becoming too great? (2) Does the patient wish to indicate in this way the suddenness of the change in her life through the shock? (In fact, she became an obstinate child, difficult to manage.) Or (3) was this really provoked by my hurting her unexpectedly (admittedly sensitized by her previous history)?

General conclusion: the rhythm, the suddenness or slowness in the change of resistance and transference may also represent autosymbolically parts of the previous history.

Another confirmation of the importance of literally free associations.

Occasional need to come out of passivity and, without threatening, to urge energetically towards greater depth.

4.8.1931

On Masochistic Orgasm

B.’s dream: She walks on her knees; under her knees the torn-off right and left leg of an animal, whose head faces backwards between the legs of the dreamer. The head is triangular, like a fox’s. She passes a butcher’s shop and there sees how a huge man with one skilful stroke cuts in two a similar small animal. In this moment the dreamer feels pain in her genitals, looks between her legs, sees there the animal dragged along and similarly cut in two, and suddenly notices that she herself has a long slit between her legs on the painful spot.

The whole scene is an attempt to displace the past or just happening violation to another male being, in particular to his penis. A huge man slits not her but an animal in the butcher’s shop, then an animal between the dreamer’s legs, and only the pain on awakening shows that the operation has been performed on herself. The moment of the orgasm is indicated first by the fact that after this scene a ‘masculine ejaculation’ with strong flow has taken place, and second by another dream fragment in which three girl friends handle something very clumsily. She thereby expresses her admiration of the cruel but confident man in contrast to the woman, however masculine.

Normal orgasm seems to be the meeting of the two tendencies to activity. The love relation apparently comes about—neither in Subject A nor in Subject B—but between the two. Love therefore is neither egoism nor altruism, but mutualism, an exchange of feelings. The sadist is a complete egoist. When overpowered by a sadist, at the moment of his ejaculation into a vagina which is mentally completely unprepared and unable to respond: the woman’s first reaction is shock, i.e. fear of death and dissolution; the second a plastic empathy into the sadist’s emotions, a hallucinatory masculine identification. The therapy consists in the unmasking of the weakness behind the masculinity, the tolerance of the fear of death, even the admiration. Chiefly, however, the desire for reciprocated love as a counterbalance.

31.12.1931

Trauma and Anxiety

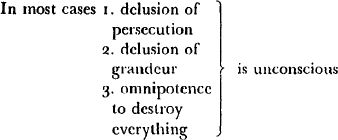

Anxiety is the direct sequel of each trauma. It consists in the feeling of inability to adapt oneself to the unpleasure situation by (1) withdrawing oneself from the stimulus (flight), (2) by removing the stimulus (annihilation of the external force). Rescue fails to appear. Hope of rescue appears out of the question. Unpleasure increases and demands ‘outlet’.1 Self-destruction as releasing some anxiety is preferred to silent toleration. Easiest to destroy in ourselves is the cs—the integration of mental images into a unit (physical unit is not such an easy prey to the impulses of self-destruction): Disorientation

Dm.: not she outraged,3 she is the father.

U.: he is strong, has colossal success in business (this fantasy is feared as mad).

Anxiety is fear of madness, but transformed. In the paranoiac the tendency to protect oneself (to ward off dangers) outweighs the wholly helpless anxiety.

Analysis must penetrate all these layers.

Dm.: must see that she intends to kill by roundabout ways and can only live with this fantasy. In the analysis she sees that the analyst understands her—that she is not bad, that she must kill—and knows that she has been, and is, inexpressibly good and would still like to be so in the future. Under these conditions she admits her weakness and badness (and confesses that she wanted to steal my ideas, etc.).

I. and S. I allowed to go away in anger instead of protesting against their desire to cut me to pieces.

IV

(1932 and undated)

10.6.1932

Fakirism

Production of organs for the purpose of ‘outlet’.1 By this, organism frees itself from ruinous tension (sensibility). The reactions are displaced somewhere else … into the future, into future possibilities which are more satisfactory. One enjoys the better future in order to forget the bad present.

That is repression.

Counter-cathexis of unpleasure with pleasure images.

Query: is such a makeshift organ capable of creating something real?

Can it influence the photographic plate? Allegedly yes. After all, it is also matter, only of a much more mobile nature (of finer structure).

One must not be so selfish, if one would like to reach and use the outer sphere. Out there, there is no (or much less) friction—only mutual yielding. Is this the principle of kindness, of mutual regard?

The fact that things can be influenced (are capable of tolerating unpleasure) is in itself proof of the existence of the II (kindness) principle.2

Death instinct? Only death (damage)3 of the individual.

Is it possible (?) to make friends with the ucs? (free-flowing, extra organic expression).

COURAGE FOR MADNESS

WITHOUT ANXIETY.

Has one then still the desire to find the way back to everyday life? And: is one then still capable of passions at all?

Biarritz, 14.9.1932

The Three Main Principles

The integration of knowledge about the Universe can be compared to the finding of the centre of gravity of a multitude of interconnected elements. Up to now I have thought of only two principles which can be grasped by man’s understanding: the principle of egoism or of autarchy according to which an isolated part of the world-total (organism) possesses in itself—as far as possible—independent of its environment, all the conditions for its own existence or development and tries to preserve them. The corresponding scientific attitude is extreme materialism and mechanism (Freud) and denial of the real existence of ‘groups’ (family, nation, horde, mankind, etc., Róheim). The minimum (?) or the complete absence (!) of ‘considerations’, or of altruistic tendencies, that go beyond the limits of egotistic needs or of the favourable returns for the welfare of the individual, are the logical sequel of this train of thought.

Another principle is that of universality; only groups, only world-total, only associations exist; individuals are ‘unreal’, as far as they believe themselves to exist outside these associations and neglect the relations between individuals (hatred, love) while leading a kind of narcissistic dream-life. Egoism is ‘unreal’ and altruism, i.e. mutual consideration, identification are justified—peace, harmony, voluntary renunciation are desirable because they alone are in conformity with reality.

A third point of view could attempt to do justice to those two opposites and, as it were, to try to find a point of view (centre of gravity) which comprehends both extremes. This would regard universalism as an attempt on the part of nature, uninfluenced by pre-existing autarchy-tendencies, at restoring mutual identification and with it peace and harmony (death instinct). On the other hand, egoism as another, more successful attempt by nature to create in decentralized forms organizations to preserve quiescence. (Protection against stimuli): (Life-instinct): Man is a very well-developed microcosmic integration; one could even think of the possibility that man might succeed in centring the whole external world around himself.

The furthest going unification would recognize the existence of both tendencies and regard, for instance, the feeling of guilt as an automatic signal that the boundaries created by reality had been crossed either in the direction of egoism or of altruism. Consequently there are two kinds of guilt feelings: first, if more has been given to the environment (groups, etc.) than is tolerable for the ego, then the ego has been sinned against; sequel: ego-indebtedness, culpability because of offending or neglecting the ego. And secondly, external-world- (group-) indebtedness: neglecting and offending altruistic obligations, i.e. what is commonly called social guilt. (Until now only this form and this motive of guilt have been recognized.)

Yet all this is only speculation, so long as cases fail to prove to my satisfaction that the A.B.C.-Principles and the A.- and B.-guilt do really exist. Neurasthenia was described by me a long time ago as having sinned against one’s own ego, as ego-indebtedness (masturbation, forced stripping the ego of libido, melancholia subjectiva, or egoistica) … Anxiety neurosis: retention of the libido beyond the measure demanded by narcissism … guilt towards others, towards the external world; hoarding of libido (‘thesauring’); repression of the tendency to give to others (out of the surplus)…. In the case of the identification reaction of a child subjected to early traumatic attack, neurasthenia and subjective-egoistic melancholia might be the consequences (suppressed is the feeling of weakness/inferiority/, pressed to the fore are vigour and efficiency, which, however, easily come to grief). (Forced libido-sequels.) With libido-frustration: anxiety.

Is in both cases rage because of enforced or frustrated love the first reaction? and is this rage identical in both cases?

Biarritz, 19.11.1932

On Shock (Erschütterung)

Shock=annihilation of self-regard—of the ability to put up a resistance, and to act and think in defence of one’s own self; perhaps even the organs which secure self-preservation give up their function or reduce it to a minimum. (The word Erschütterung is derived from schütten, i.e. to become ‘unfest, unsolid’, to lose one’s own form and to adopt easily and without resistance, an imposed form—‘like a sack of flour’). Shock always comes upon one unprepared. It must needs be preceded by a feeling of security, in which, because of the subsequent events, one feels deceived; one trusted in the external world too much before; after, too little or not at all. One had to have overestimated one’s own powers and to have lived under the delusion that such things could not happen, not to me.

Shock can be purely physical, purely moral, or both physical and moral. Physical shock is always moral also; moral shock may create a trauma without any physical accompaniment.

The problem is: Is there, in the case of shock, no reaction (defence), or does the momentary, transitory attempt at defence prove to be so weak that it is immediately abandoned? Our self-regard is inclined to give preference to the latter proposition; an unresisting surrender is unacceptable even as an idea. Moreover, we notice that in nature even the weakest puts up a certain resistance. (Even the worm will turn.) In any case flexibilitas cerea and death are examples of lack of resistance and of phenomena of disintegration. This may lead to atom-death, and finally to the cessation of all material existence whatsoever, Perhaps to temporary or permanent ‘univcrsalism’—the creation of a distance, viewed from which the shock appears minimal or self-evident.

Biarritz, 19.9.1932

Suggestion=Action without one’s own Will (with the will of another person. Case: Inability to walk. Fatigue with pains, exhaustion. Someone takes us by the arm (without helping physically)—we lean (depend) on this person who directs each of our steps. We think of everything possible and watch only the direction indicated by this person, which we follow. Suddenly walking becomes laborious, each action seems to demand a double expenditure of effort: the decision and the performance. Incapacity to decide (weakness) may make the simplest movement difficult and exhausting. Surrendering the will (decision) to someone else makes the same action easy.

Muscular activity itself here is undisturbed, smooth. Only the will to action is paralysed. This must be contributed by someone else. In hysterical paralysis this will is lacking and must be transmitted by way of ‘suggestion’ by someone else. How and by what ways and means?: (1) Voice, (2) Percussion sound (music, drum), (3) Transmitting the idea ‘you can do it’, ‘I am going to help you!’

Hysteria is regression to the state of complete lack of will and to acceptance of another’s will as in childhood (child on mother’s arm): (1) Mother takes care of the whole of locomotion, (2) Child can walk if supported and directed (not without this help). The safe feeling, that the power supporting us will not let us fall.

Question: is suggestion (healing) necessary after (or even during) the analysis? When relaxation is very deep, a depth may be reached in which only well-intentioned and kindly directed help must replace the absent or lacking act of will. Perhaps as reparation for a former suggestion which demanded only obedience; this time a suggestion which awakens (or bestows) a power of individuality must be given. Consequently: (1) Regression to weakness, (2) Suggestion of power, increase of self-esteem in place of the previous suggestion of obedience (relapse into the state of absence of will, and the counter-suggestion against the frightening earlier suggestion of obedience).

Luchon, 26.11.1932

Repression cs-(ego-) functions are pushed out (displaced) from the cerebrospinal into the endocrine system. The body begins to think, to speak, to will, to ‘act out’ instead of only carrying out (cerebrospinal) ego-functions.

The facility for it appears to be present already in a rudimentary form in the embryo. But what is possible for the embryo is harmful for the adult. It is harmful when the head, instead of thinking, acts as the genital (emission=cerebral haemorrhage); it is likewise harmful when the genital starts to think instead of carrying out its function (genitalization of the head and cerebralization of the genital).

Tripartitum:

Organic illness: when the chemistry of the body expresses ucs thoughts and emotions instead of caring for its own integrity. Perhaps still stronger, more destructive emotions and impulses (murderous intentions) which change into self-destruction. Paralysis in place of aggression (revenge). Bursting, shaken to bits. What causes the change of direction? (1. quantitatively unbearable aggression [gun] 2. premodelled as trauma.)

26.9.1932

Scheme of Organizations

The individual compounds endeavour to maintain their own particular existence against the influence—dividing or agglutinating influence—of the external world.

The developments of the organizations are processes of progressive abstraction.