Hope for the Future of the Postindustrial City

Well I went back to Ohio | But my city was gone | There was no train station | There was no downtown

“My City Was Gone” (1982)—The Pretenders (music and lyrics by Chrissie Hynde)

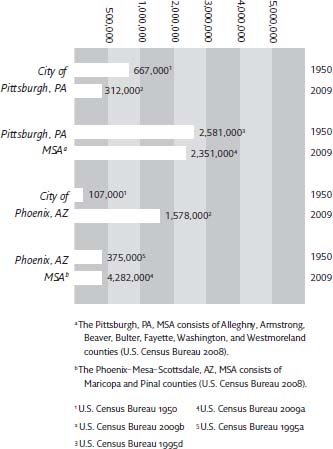

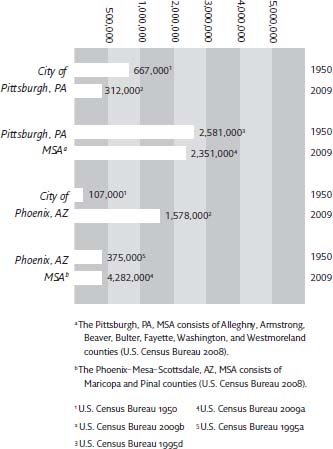

The term “postindustrial” was first popularized by Daniel Bell in his 1973 book The Coming of Post-industrial Society, in which he forecast that mature national economies were moving and would continue to move from being manufacturing based to service based. The United States indeed went in that direction and prospered overall. What Bell did not predict were the severe regional disparities that would result between the so-called Rust Belt cities of the Northeast and Midwest and the Sun Belt cities of the South and Southwest. Over the next 40 years, Rust Belt cities were characterized by depopulation, disinvestment, and decline while Sun Belt cities were characterized by population explosion, economic growth, and sprawl. Graph 1.1 illustrates the magnitude of this geographic shift, comparing population change in two representative cities, Pittsburgh (Rust Belt) and Phoenix (Sun Belt), and their respective Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAS) between 1950 and 2009. The symptoms of decline in the Rust Belt are well known, the causes have been identified, and the diagnosis has been consistently grim for cities like Detroit and Youngstown, Ohio.

This chapter will present a more optimistic future for the postindustrial cities of the Rust Belt. The transformation of the “Steel City” of Pittsburgh into a technology and financial center will be featured as a case study. Although “Shrinking Cities” — a term some consider pejorative — have indeed bled jobs and people for decades in the Northeast and Midwest, the cities themselves remain national treasures not to be tossed aside like the silver ghost towns of Nevada. Shrinking cites with well-planned postindustrial redevelopments, such as SynergiCity, have the best attributes of “Smart Growth,” including walkable neighborhoods, affordable housing, historic downtowns and main streets, strong universities and hospitals, cultural amenities, parks, unused infrastructure capacity, development density sufficient to support public transit, and abundant water.

By contrast, the burgeoning cities of the Sun Belt are low-density, auto-dependent, and surviving on ever-diminishing supplies of borrowed water. Sun Belt economies have been driven not by diverse economies but by the business of growth itself, such as home building and construction, which the Great Recession of 2008-2009 revealed as illusory and unsustainable (Florida 2010). A new terminology now seems appropriate. Rust Belt becomes “Water Belt.” Sun Belt becomes “Drought Belt.”

We cannot undo the post-1950 global economic patterns that led to these regional inequities, but we can provide strategies for the rebirth of our industrial heartland in the postindustrial economy, especially if redevelopment is tackled on a regional basis, not just in the central cities. The regional cities of the Water Belt may now, half a century later, have regained a competitive advantage. They have space to grow internally on vacant and underutilized land. They have adaptable buildings and walkable neighborhoods. They have roads and utilities in place. They have strong institutional resources. They are places of authenticity and heritage. They have the persistence, strength, and resiliency of the people who did not leave. They have water.

GRAPH 1.1. Populations of Pittsburgh (Rust Belt) v. Phoenix (Sun Belt) in 1950 and 2009. (Courtesy of Donald Carter)

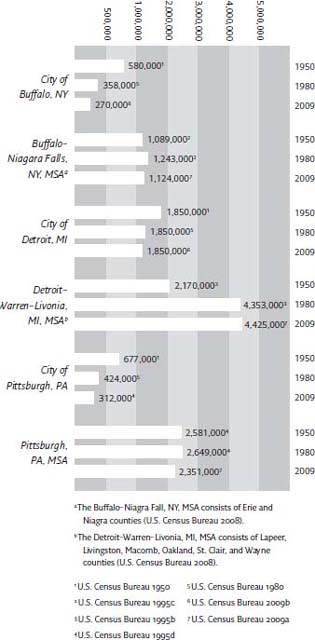

GRAPH 1.2. Population Change in Buffalo, Detroit, and Pittsburgh, 1950-2009. (Courtesy of Donald Carter)

There is every reason to believe that many of these American heartland cities can, with proper planning and investment, repopulate and prosper as some of the expanding U.S. population (300 million people in 2010 to 400 million in 2050) migrates to sustainable and livable cities with high quality of life, affordability, amenities, and economic opportunity. This can be the future of American postindustrial cities and can be a replicable model for postindustrial cities internationally.

Pathology of Postindustrial Cities

Well we’re living here in Allentown

And they’re closing all the factories down

Out in Bethlehem they’re killing time

Filling out forms, standing in line

“Allentown” (1982) (music and lyrics by Billy Joel)

There is an established pathology for American postindustrial cities. The symptoms are well known and follow a well-documented pattern: loss of industrial jobs; subsequent loss of support and multiplier jobs; out-migration and population loss; lack of private investment; tax base decline; neglect and disinvestment in infrastructure and public services; abandoned factories; brownfields; vacant houses; vacant land; declining real estate values; loss of family equity; increased poverty; and finally, loss of hope and psychological depression.

The United States is not alone in experiencing postindustrial decline. In 1988, the International Remaking Cities Conference was held in Pittsburgh with over 350 delegates from industrial regions such as the Ruhr Valley in Germany, the Midlands in England, and the Monongahela Valley in Pittsburgh. Urban designers, market economists, architects, and citizens shared ideas for the reinvigoration of postindustrial cities that informed subsequent redevelopment policy in the Pittsburgh region (Davis 1989).

Graph 1.2 tracks population for three representative postindustrial U.S. cities and their respective MSAS from 1950 to 2008: Buffalo, Pittsburgh, and Detroit. Note that the central cities suffered large declines in population compared to their regions, which experienced moderate growth or decline. This reflects the 65-year pattern of suburbanization of America that accompanied the emptying out of the urban core, a national trend termed by Rolf Pendall (2003) as “sprawl without growth.”

The causes of the decline of postindustrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest are likewise well known: loss of basic industries to low-cost, nonunion producers in the Sun Belt, Far East, and Mexico; an entrepreneurial vacuum creating no new industries to replace the lost jobs; the lure of suburbia; racial conflict; white flight; middle-class flight; concentration of poverty and crime in the urban core; investment in highways over public transit; steady decline of funding for essential services such as schools, parks, and public works; and the overall deterioration of the built environment, including streets, bridges, and buildings. Why stay?

The standard prognosis for postindustrial cities has been bleak. At worst, these cities are dead and will not come back. At best, they will become Shrinking Cities populated by an increasingly aged and poor population. They will have to do less with less. Like Camden, New Jersey, they will become “wards of the State” (Gillette 2005: 39). Whole parts of cities will be abandoned. Indeed, some of this is happening already in Detroit, Buffalo, and Flint, Michigan, where “managed decline” is the new strategy (Oswalt 2006a; Pallagst et al. 2009) and once-vibrant neighborhoods are being transformed into urban farms, recreational amenities, green infrastructure zones, and natural areas. Such downsizing strategies have been successfully adopted in depopulated cities in the former East Germany in an attempt to match cities’ footprints to their new populations (Müller 2010). This still may be the fate of some cities. But there is an alternative scenario, best exemplified by the remaking of Pittsburgh, the quintessential industrial city and personification of the Rust Belt.

What Happened in Pittsburgh

Now Main Street’s whitewashed windows and vacant stores

Seems like there ain’t nobody wants to come down here no more

They’re closing down the textile mill across the railroad tracks

Foreman says these jobs are going boys and they ain’t coming back to

Your hometown, your hometown, your hometown, your hometown

“My Hometown” (Music and lyrics by Bruce Springsteen, 1984)

The song lyrics quoted about the breakdown of the Midwest’s great industrial cities by Chrissie Hynde, Billy Joel, and Bruce Springsteen are from the 1980s. That is not a coincidence; it was indeed a dire time. Pittsburgh and many of its sister cities across the Northeast and Midwest lost their industrial bases in the space of a few years and went into precipitous, seemingly irreversible decline. That has not been the outcome for Pittsburgh. There are lessons to be learned in recounting how Pittsburgh was transformed in one generation from “Steel City” to “Knowledge City” (Carnegie Mellon University 2002) and how it became “a center for technology and green jobs, health care and education” (Obama 2010). The remaking of Pittsburgh did not happen by chance or luck. It was the result of a realistic assessment of assets and problems, imaginative long-range economic regional planning, a shared vision, a tradition of successful public-private partnerships, involvement of concerned private organizations, authentic citizen participation, strategic investments, organized feedback and evaluation, and patience to stay the course. First, a brief history of industrial Pittsburgh is in order to understand the city’s underlying “DNA.” Its current vibrancy is built on the legacy of three successive eras: Industrial Powerhouse (1865-1945); Renaissance (1945-1985); and Regrouping and Transformation (1985-present).

FIGURE 1.1. Downtown Pittsburgh (daytime), c. 1940. Street lights were turned on during the day. Businessmen put on clean shirts in the afternoon. (Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of Smoke Control Lantern Slide Collection, Archives Services Center, University of Pittsburgh)

INDUSTRIAL POWERHOUSE (1865-1945)

The unprecedented industrial growth of Pittsburgh between the Civil War and World War I was the foundation for all that followed. That expansive era was made possible by nearby natural resources, particularly coal, oil, and gas; good transportation connections via rivers, canals, and railroads; an abundance of immigrant workers; and the genius and resourcefulness of a remarkable group of entrepreneurs: Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, H. J. Heinz, Andrew Mellon, and George Westinghouse, to name the most famous.

Pittsburgh was truly a boomtown, albeit a polluted one, indelibly characterized by James Parton in 1868 as “Hell with the lid taken off” (Cronin 2008). In the 1870s, Pittsburgh was called the “‘Forge of the Universe,’ turning out half the glass, half the iron, and much of the oil produced in the United States” (Toker 2009). Between World War I and World War II, Pittsburgh maintained its place as one of the largest industrial centers in the world, despite suffering an economic downturn during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The armaments needed for World War II brought the city back to full employment as new factories were built overnight and pollution poured from the smokestacks and into the rivers. Streetlights were on at midday. Pollution meant prosperity (fig. 1.1).

In 1943, as World War II raged, Pittsburgh civic and business leaders, led by Democrat mayor David L. Lawrence and Republican business magnate Richard K. Mellon, son of the famed banker Andrew Mellon, determined that cleaning up the image of the city was critically important. This era has been dubbed “Renaissance I”; it included a smoke control ordinance, locks and dams on the rivers to prevent flooding, four major urban redevelopment projects (Gateway Center, Lower Hill, North Side, and East Liberty), and an urban highway system. Corporate headquarters were built for U.S. Steel, Alcoa, Mellon Bank, and Westinghouse. A new key player on the private side, the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, was formed in 1945 and was comprised of the CEOs of Pittsburgh’s corporations, banks, private foundations, and universities.

“Renaissance II” is associated with Mayor Richard Caliguiri (1977-1988). During his time in office, a $2 billion downtown development boom occurred with six new office towers and a convention center hotel (fig. 1.2). The construction of a light rail subway system downtown and an exclusive busway to the eastern part of the city further strengthened the employment function of the urban core. Caliguiri also developed strategies for neighborhood revitalization, including housing rehabilitation and new infill development. Midway through his term of office, the steel industry in the Pittsburgh region collapsed, and 133,000 manufacturing jobs were lost in the span of eight years (Bureau of Economic Analysis 2010).

REGROUPING AND TRANSFORMATION (1985-2010)

Not only did the Pittsburgh region lose basic manufacturing jobs, but in 1985, Gulf Oil, a Fortune 500 company founded and headquartered in Pittsburgh, ceased to exist as it merged with Chevron, moving all operations to Houston and San Francisco. Rockwell International and Koppers likewise disappeared in mergers and acquisitions. Westinghouse faced financial problems that led to its eventual breakup into separate companies and subsequent loss of jobs in Pittsburgh. Things looked bleak. Families left the region for points south and west in quest of jobs. “Rust Belt” started to sound about right.

FIGURE 1.2. View of Downtown Pittsburgh, “The Golden Triangle,” 2008. The Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet to form the Ohio River. Over 300,000 persons work downtown. (Courtesy of Bobak Ha’Eri)

Improbably, in the midst of these losses, Rand McNally’s Places Rated Almanac crowned Pittsburgh the nation’s “Most Livable City” in 1985, displacing Atlanta, to its disbelief and dismay, and producing derisive snickers coast to coast. That surprising designation offers an important key to the continued resilience of Pittsburgh: quality of life. The city received medium and high marks for climate and terrain, housing, health care, transportation, education, the arts, recreation, and economic outlook. In essence, the Most Livable City designation was and is a measure of quality of life, and Pittsburgh was exceptional. Pittsburgh was named Most Livable City by the Places Rated Almanac again in 2007. In 2009, the British magazine Economist rated Pittsburgh the Most Livable U.S. City and twenty-ninth in the world. A year later, Forbes named metropolitan Pittsburgh the Most Livable City in the country and the Best Place to Buy a Home (Kalson 2010). Other recent accolades for the Pittsburgh region include “Number 1 Commercial Real Estate Market” in 2009, from Moody’s Investors Service, and “Second Best Place to Raise Kids,” from Business Week (2008).

Nevertheless, it was clear in 1985 that an economy based on heavy manufacturing was over. The often-quoted dictum from the richest American ever, Andrew Carnegie — “Put all your eggs in one basket, and then watch that basket” — does not apply if the eggs and the basket have disappeared. In the 1980s, Pittsburgh still had the key indicators of quality of life, but if well-paying jobs continued to disappear, so would quality of life.

Something had to be done, and it was. Between 1985 and 1995, the regional economic agenda for the next 25 years was set. This process involved leaders in the public and private sectors, in much the same way Renaissances I and II had. But something else also began to happen — an unprecedented bubbling up of quality-of-life initiatives from individuals, volunteer groups, and nongovernmental organizations, many of them in turn funded by the corporations and foundations. There was receptivity to new things and willingness to take risks. This bottom-up energy was especially exhibited by young adults in their twenties and thirties who began populating older neighborhoods, renovating houses, creating art, and starting new businesses. Two important civic groups, the Pittsburgh Urban Magnet Program (PUMP) and GroundZero Action Network, were created by and for young adults. Word of mouth fed a trickle and then a steady flow of young expatriate Pittsburghers who were coming back home (“boomerangs”) and young newcomers eager to take advantage of the low cost of living, available jobs, and a vibrant cultural scene.

Charting the changes from the mid-1980s, when all seemed lost, makes a remarkable story. The first important transformative effort after the collapse of Big Steel was the formation in 1985 of Strategy 21, a consortium of the city of Pittsburgh, the county of Allegheny, the University of Pittsburgh, and Carnegie Mellon University that developed a strategy “to transform the economy of the Pittsburgh/Allegheny region as it enters the 21st century” (Strategy 21 1985: 1). Strong emphasis was placed on creating a diversified economy to take “maximum advantage of emerging economic trends toward advanced technology and international marketing and communications systems” (Strategy 21 1985: 1). The Allegheny Conference on Community Development and local foundations were silent partners and major funders of the effort. Strategy 21 projects included the Software Engineering Institute (1986), the Pittsburgh Super Computing Center (1986), a new international airport terminal (1992), and major infrastructure improvements and brownfield reclamation projects throughout the region.

In the 25 years since 1985, manufacturing jobs have decreased by 40%, but total employment in the Pittsburgh region has grown by 13%, with growth in the health care, education, research, technology, finance, and arts sectors (Bureau of Economic Analysis 2010). New research institutes were created, including the Pittsburgh Transplantation Institute, National Robotics Center, and Gates Center for Computer Science. Scores of new nongovernmental organizations emerged, including Leadership Pittsburgh, the Green Building Alliance, Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership, Sustainable Pittsburgh, Riverlife, and Bike Pittsburgh.

New cultural organizations joined the four established world-class institutions (the Pittsburgh Symphony, Pittsburgh Opera, Pittsburgh Ballet, and Carnegie Museum), including the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust (with four downtown theaters), the Andy Warhol Museum, the Senator John Heinz History Center, and the August Wilson Center for African American Culture. In addition, art galleries, live music venues, performance groups, and neighborhood arts initiatives emerged, accompanied by new coffee shops and restaurants. Four large public buildings were built downtown: the David L. Lawrence Convention Center, PNC Park (baseball), Heinz Field (football), and the Consol Energy Center (hockey).

The most recent transformative project is the Pittsburgh Promise. Based on the highly successful 2005 Kalamazoo Promise, Pittsburgh Promise provides college scholarships for graduates of the Pittsburgh public schools or one of its charter high schools who have maintained a grade point average of 2.5 and a 90% attendance record from the ninth grade. The Pittsburgh Promise was jump-started in 2009 with a $100 million grant and pledge from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), with substantial additional funding and matching contributions anticipated from businesses, foundations, and individuals over the next nine years to reach the goal of $250 million.

Several demographic trends are promising. In the last 25 years, regional population loss has slowed each decade, to the point that the population has now stabilized at about 2.4 million, with a slight increase projected for 2010 (Rotstein 2010). The region’s net domestic out-migration in 2007 was lower than that of 16 of the top 40 regions, including Boston, Chicago, San Diego, and Silicon Valley (Miller 2008). The median age of employed Pittsburghers has started to drop, as younger people are drawn to the quality of life and a steady economy (Bowling 2008). Even senior citizens are finding Pittsburgh an attractive relocation destination. A study by the University of Pittsburgh and the Rand Corporation found that one-third of the elderly who moved to Pittsburgh between 1995 and 2000 migrated from Florida (Zlatos 2006).

Thorny issues nevertheless remain for the Pittsburgh region, including a surplus of vacant land and buildings; declining neighborhoods; racial and socioeconomic inequities; aging infrastructure, such as combined sewer overflows and bridge maintenance; stressed municipal finances; fragmented government; and an underfunded public transit system. These problems are shared with most of the deindustrialized cities in the Northeast and Midwest as they struggle to make a comeback. Philadelphia, Youngstown, Pennsylvania, Cleveland, and Detroit are exploring innovative approaches to the vacant land problem, including urban agriculture, return of nature to the city, and densifying certain neighborhoods along with dedensifying others. Many postindustrial cities are striving to capitalize on the strengths of their universities and medical centers. Yet Pittsburgh, of all those cities in the Northeast and Midwest, stands out today as exemplary in its transformation given the circumstances it faced in 1985. What lessons from Pittsburgh can be replicated in other postindustrial cities?

Lessons from Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh’s path of recovery over the last 25 years, although difficult, is an example of how to build on current assets and respect past strengths while boldly embracing the future. The Pittsburgh story suggests that hope for the future of postindustrial cities will depend on the hard work and creativity of today’s citizens, institutions, businesses, and governments working together with a shared vision. Below are 10 lessons for postindustrial cities from the remaking of Pittsburgh.

POPULATION GROWTH IS NOT NECESSARILY THE ANSWER

For so-called shrinking cities, the typical lament has been “If only we had more people. . . .” That is the wrong metric. Most of the deindustrialized regions of the Northeast and Midwest, although not growing, are in fact viable even at their reduced size. Many, like Pittsburgh, have stabilized in population at a size that can provide the services and amenities of world-class regions. For example, the population of the Pittsburgh region (2.4 million) is equal to or greater than 75% of the major metropolitan regions of Europe. This includes Copenhagen (2.4 million), Zurich (2.5), Vienna (2.2), Stockholm (2.2), Turin (2.2), and Dublin (1.6), to name just a few (OECD 2006). It is not likely that any of these regions will grow substantially in the next 20 years, but they will remain vibrant and viable. The same can be said about Pittsburgh.

Population size is not the issue, nor is population growth. Paul Gottlieb, in his 2002 paper for the Brookings Institution Growth without Growth: An Alternative Economic Development Goal for Metropolitan Areas, makes the argument that per capita growth in income is more important than population growth. He groups U.S. cities into four categories: Wealth Builders; Population Magnets; High-Growth Traditional; and Low-Growth Traditional. He argues that Wealth Builder cities tend to be in the “Frost Belt” and have high-tech economies. According to his analysis, the top three Wealth Builder cities are St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and Boston. Population Magnets like San Diego or Orlando tend to be in the Sun Belt and have economies based on tourism and low-paying, low-tech jobs. Gottlieb concludes: “We do not normally think of metropolitan areas like Milwaukee, St. Louis, or Pittsburgh as economic success stories, but by this particular welfare measure they are” (Gottlieb 2002: 25).

HAVE A LONG-TERM REGIONAL VISION

The unit of economic competitiveness is no longer the central city but the metropolitan region (Calthorpe and Fulton 2001). Despite the fragmentation of local government, the Pittsburgh region has been able to forge a unified economic vision.

Following Strategy 21 in 1985, a second regional visioning effort was initiated in 1993, with the publication of a white paper by Robert Mehrabian, president of Carnegie Mellon University. Commissioned by the Allegheny Conference, the study compared the Pittsburgh region’s economic indicators to those of the 24 largest regions in the country. The comparison was sobering. From 1970 to 1990, the Pittsburgh region had the largest decline in manufacturing jobs, the slowest growth in service jobs, and the greatest loss of population. On the other hand, the report identified inherent strengths on which to base an economic recovery: a strong downtown; a concentration of university and corporate research; a dedicated and trained workforce; a growing core of high-value, high-tech manufacturing and specialty companies; and an extraordinary range of high-quality recreational and cultural amenities. The report proposed a nine-month public engagement process to develop a consensus vision for the region. That process involved over 5,000 people and resulted in a report, The Greater Pittsburgh Region: Working Together to Compete Globally, published the following year (Mehrabian and O’Brien 1994). The Working Together Consortium, comprised of representatives from government, business, labor, education, community and religious organizations, and counties throughout the region, was subsequently formed to implement the plan.

The Strategic Investment Fund was established in 1996 by private corporations and foundations to complement and support public sector investments in economic development. Originally endowed with $40 million, it received a second round of capitalization of $30 million in 2002. The Fund provides gap-financing loans of $500,000–$4,000,000 for two categories of development: regional core investments, and industrial site reuse and technology development.

One of the most important actions of the Working Together Consortium affecting quality of life was the enactment of State Law 77, which enabled the adoption of a 1% added sales tax in Allegheny County in 1994. The 1% tax increment was split three ways: 0.25% to municipalities for tax relief; 0.25% to Allegheny County for tax relief; and 0.5% to the newly created Regional Asset District. The portion of the tax designated for the Regional Asset District provides operating support to the Pittsburgh Zoo, National Aviary, Phipps Conservatory, Carnegie Museums, Carnegie Libraries, County Parks, Convention Center, stadiums, and many smaller cultural organizations. From 1994 to 2010, the Regional Asset District has provided $1.1 billion to these regional assets.

A further regional initiative, “Power of 32,” began in 2010 with the goal of creating a regional vision for the 32 counties surrounding Pittsburgh. With the tag line “32 Counties, 4 States, 1 Vision,” Power of 32 will gather 4.2 million people from southwestern Pennsylvania, eastern Ohio, northern West Virginia, and western Maryland in a large-scale visioning project modeled after “Envision Utah” and “Louisiana Speaks.”

MAKE LOCAL GOVERNMENT MORE EFFICIENT

The implementation of the Regional Asset District sales tax in 1995, in effect a regional tax-sharing mechanism, was an important first step in restructuring local government, a major goal of the Working Together Consortium. It was followed in 1998 by a ballot initiative changing the governance of Allegheny County from three elected county commissioners, with its foundation in an outmoded rural model, to an elected county executive and 15 councilors. In 2005, Allegheny County voters approved the conversion of previously elected offices, such as the clerk of courts and coroner, to merit-based appointments by the county executive and county council. The city of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County began discussions regarding city-county consolidation based on successful consolidations in Indianapolis/Marion County and Louisville/Jefferson County. However, other than a city-county summit in 2004 and a 2008 public agreement between the current mayor and county executive to work toward consolidation, there has been little progress in merging departments. As they have in the past, when progress has stalled on important regional issues, the local foundation community in July 2010 stepped in to create and fund the Allegheny Forum. The Forum consists of 300 invited residents representing the county’s demographic and partisan makeup who have been tasked with simplifying the “gnarled, centuries-old issue of divided governance.” Their first assignment will be to look at the sustainability of maintaining 109 separate police forces across Allegheny County.

FOSTER PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS

The remaking of Pittsburgh could not have taken place in the last 65 years without the extraordinary public-private partnerships described previously. Government, corporations, and philanthropic foundations worked together on issue after issue, whether environmental cleanup, transit, or public schools. It may be difficult for other cities to replicate the large behind-the-scenes investments by Pittsburgh’s private foundations that bear the names of the industrialists and financiers of the Industrial Powerhouse years (Mellon, Heinz, McCune, Benedum, Hillman, Hunt, and Buhl, among others). This may be one area where Pittsburgh has a decided advantage. Nevertheless, philanthropic and corporate resources are available in every community. The important lesson is to engage local foundations and corporations, whoever they are, in the remaking effort. For example, an adventuresome, farsighted Chattanooga foundation, the Lyndhurst Foundation, spearheaded the acclaimed revitalization of the Chattanooga downtown and riverfront.

DIVERSIFY THE ECONOMY

The city of Pittsburgh’s decisions in the 1980s and 1990s to diversify the economy into high-tech industries and research have paid large dividends. Today, the Pittsburgh region has a smaller share of employment in manufacturing than the national average, but its share of employment in the education and health services industry is 1.5 times larger than the average in the United States (Miller and Rudick 2007). All those lost manufacturing jobs (and more) were replaced over three decades by jobs in research, medicine, finance, and services and in new fields such as robotics, information technology, and green industries. This was a deliberate strategy backed by studies and strategic investments by government, corporations, universities, and foundations, working together with one shared vision. An indicator of this strategy is that the Pittsburgh region’s unemployment rate has been lower than or equal to the national rate since early 2007 (Rotstein 2010).

STRENGTHEN THE CORE

Despite its economic woes beginning in the mid-1980s, the city of Pittsburgh, the heart of the region, had significant assets: a strong downtown; distinct historic and walkable neighborhoods; two major research universities; a world-renowned medical center; a well-used public transit system; unrivaled cultural amenities for a city of its size; and a critical mass of large philanthropic foundations with a commitment to investing in the region.

Beginning with Renaissance I after World War II and continuing today, a major goal of community leaders has been to strengthen the central city of Pittsburgh and its downtown. Some mistakes were made along the way, as in other cities, most notably ill-conceived urban renewal projects that displaced low-income residents and businesses, and highway projects that severed neighborhoods from the rest of the city. But the overall result has been good, as the downtown remains the economic hub of the region, with employers providing 140,000 jobs, including corporations, banks, law firms, government offices, professional offices, hotels, two department stores, hundreds of retail stores and restaurants, and five performing arts theaters. The major public facilities built in the last 10 years (two stadiums, the arena, and the convention center) are located downtown and were central accomplishments of the Regional Destination Strategy of the Working Together Consortium. Downtown housing is increasing, aided by government programs and philanthropic efforts, and a continuous network of green spaces has been created along the rivers in the urban core. Parallel investments in housing, amenities, economic development, and brownfield redevelopment have been made in Pittsburgh’s neighborhoods by the city under Mayor Tom Murphy (1994-2006), the Strategic Investment Fund, and other civic initiatives.

COMMIT TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

Pittsburgh pioneered the environmental cleanup of industrial pollution in the late 1940s, as described in the Renaissance section. Pittsburgh became known for leading-edge engineering and construction companies involved in brownfield remediation, air and water quality technologies, and best practices in stormwater management. In the 1990s as part of the Working Together Consortium, two new Smart Growth organizations were created: the Green Building Alliance, which predated the U.S. Green Building Council, and Sustainable Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh was ahead of the curve on “green building,” becoming a national leader in Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certified buildings, including the first LEED certified convention center, botanical conservatory, and multipurpose arena. City and county governments have sustainability coordinators. Pittsburgh corporations, universities, hospitals, and real estate developers have embraced sustainability principles in their construction programs. The Strategic Investment Fund gives special consideration in its loans to projects that include brownfield redevelopment and green technology. Sustainable development has thus become an environmental ethic and brand for Pittsburgh as well as an economic driver.

CAPITALIZE ON FRESH WATER

Fresh water resources are expected to be a key determinant worldwide of the health of all metropolitan regions in the next 50 years. Water is a finite resource — a closed system that cycles over and over from evaporation to precipitation. Only 2.5% of the world’s supply is fresh water, and two-thirds of that is frozen in Earth’s polar ice caps. The remaining 97.5% is ocean salt water unusable for human consumption, industry, or agriculture without treatment (Lange 2010).

Climate change and unsustainable development practices are creating water shortages through the world, including the United States. A 2010 study by the Natural Resources Defense Council found that one-third of all counties in the lower 48 states — more than 1,100 counties — will be subject to higher risks of water shortages by midcentury. The regions in the nation with naturally abundant and rechargeable fresh water supplies, such as Pittsburgh and the other postindustrial regions of the upper Midwest, with the Great Lakes, major rivers, and large ever-renewing underground aquifers, have a decided advantage over regions in the South and Southwest. Rapidly growing regions like Atlanta and Phoenix have exceeded their natural water supplies. Water must be borrowed from other states at great expense and usually after intense disputes over riparian rights. At the same time, their underground aquifers are being pumped out faster than they are being recharged, also at great expense. Continued growth in these regions may become untenable as the fresh water supply inexorably diminishes, while the postindustrial cities of the Midwest remain water rich.

FIGURE 1.3. Kayakers on the Allegheny River, 2008. The three rivers in Pittsburgh are lined with 25 miles of bicycle and pedestrian trails where railroad lines and factories once prevented public access. (Photo by John Altdorfer. Courtesy of John Altdorfer)

Las Vegas is the first region in the nation to reach a dangerous tipping point in water resources, as Lake Mead continues to shrink and the Owens Valley aquifer is being pumped dry (Sonoran Institute 2010). By contrast, Pittsburgh and the Midwest will continue to have abundant water for agriculture, industry, drinking, and new development, while regions in the Drought Belt may have reached their peaks and may become the Shrinking Cities of the twenty-first century. “Water is going to be more important than oil in the next 20 years,” says Dipak Jain, dean of the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois (quoted in Lippert and Efstathiou 2009).

INVEST IN EDUCATION

An educated workforce is essential to economic success, whether in remaking a city or building a new one. Pittsburgh has committed to increasing the effectiveness of its workforce over the last 25 years, and with good results. A recent report published by the University of Pittsburgh’s University Center for Social and Urban Research, comparing the educational attainment of workers aged 24 to 34 in the top 40 metropolitan areas of the nation, found that 48.1% of Pittsburghers in this cohort have obtained at least a bachelor’s degree. This puts Pittsburgh in fifth place after Boston, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Austin (Briem 2010). The deindustrialized cities of the Northeast and Midwest saw their inner-city school systems decline in enrollment, test scores, and graduation rates while the surrounding suburban school districts flourished. Central city scholarship programs like the Kalamazoo Promise counter that trend. Since the inception of the Kalamazoo Promise in 2005, enrollment in the public school system has increased 17.6%, ending 20 years of steady decline (Miller-Adams 2009). Middle-class families are moving to the city to take advantage of the scholarship program. More college preparatory courses are being offered in high school as a result. Finally, because the Kalamazoo Promise scholarships can only be used at public colleges and universities in Michigan, there is more likelihood of retaining those young people in the region when they graduate, an outcome the Pittsburgh Promise hopes to achieve.

INVEST IN QUALITY OF LIFE

Pittsburgh deserved its many citations as Most Livable City. It has also been consistently in the top 10 U.S. cities for other measures such as cultural tourism and being artist friendly. Top rankings appear every year for such quality-of-life issues as suitability to raising a family, housing affordability, bicycle friendliness, and accessibility of the outdoors. From the creation of the Regional Asset District in 1985 to the construction of 25 miles of riverfront bikeways in the 1990s and 2000s, Pittsburgh has invested heavily in amenities, including major cultural and sports facilities. Richard Florida wrote his seminal 2002 book The Rise of the Creative Class while in Pittsburgh on the faculty of Carnegie Mellon University. Funding for his initial research into amenities for young adults came from the Heinz Endowments and the Richard King Mellon Foundation, two of Pittsburgh’s largest foundations. Florida’s conclusions about the potent combination of talent, technology, tolerance, and territory validated for community leaders in Pittsburgh the importance of investing in quality of life.

There is optimism today in the Pittsburgh region, an upbeat spirit, much of it related to quality of life. Part of that is pride in having survived the collapse of the 1980s, in being named Most Livable City four times, and, of course, in winning two Super Bowls and three Stanley Cups in those years. But it is more tangible than that. People can see for themselves 25 miles of bike trails that did not exist along the rivers 10 years ago. They can see rowers and kayakers on the rivers (fig. 1.3). They can see new stadiums, new housing in once declining neighborhoods, restoration of historic buildings on main streets, an expanding arts community, neighborhood festivals, an influx of young people, and most important, new businesses and jobs.

References

Bell, Daniel. 1973. The Coming of Post-industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting. New York: Basic Books.

Bowling, Brian. 2008, September 23. “City Shifts to Younger Work Force, Census Says.” Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/news/cityregion/s_589592.htm.

Briem, Christopher. 2010, March. “Education Attainment in the Pittsburgh Regional Workforce.” Pittsburgh Economic Quarterly. www.ucsur.pitt.edu/files/peq/peq_2010-03.pdf.

Brookings Institution. 2007. Committing to Prosperity: Moving Forward on the Agenda to Renew Pennsylvania. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. 2010. Regional Economic Accounts. CA25 — Total Employment by Industry, 1985-2008. www.bea.gov/regional/reis/default.cfm?selTable=CA25.

Calthorpe, Peter, and William Fulton. 2001. The Regional City. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Carnegie Mellon University. 2002, summer. “President Bush Visits Oakland, Greets University Presidents.” Carnegie Mellon Magazine. www.cmu.edu/magazine/02summer/newsbriefs.html#bush.

Cronin, Mike. 2008, September 7. “Reactions Mixed on Comparison of City to Hell.” Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/news/specialreports/250-anniversary/s_586956.html.

Davis, Barbara, ed. 1989. Remaking Cities: Proceedings of the 1988 International Conference in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Florida, Richard. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books.

———. 2010. The Great Reset: How New Ways of Living and Working Drive Post-crash Prosperity. New York: HarperCollins.

Gillette, Howard, Jr. 2005. Camden after the Fall: Decline and Renewal in a Post-industrial City. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Gleeson, Robert E. 2004. Toward a Shared Economic Vision for Pittsburgh and Southwestern Pennsylvania: A White Paper Update. Prepared for the Center for Economic Development, H. John Heinz III School of Public Policy and Management, Carnegie Mellon University.

Gottlieb, Paul D. 2002. Growth without Growth: An Alternative Economic Development Goal for Metropolitan Areas. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Grimm, Fred. 2009, January 17. “A City Goes from Misery to Marvelous.” Miami Herald.

Grogan, Paul, and Tony Proscio. 2000. Comeback Cities: A Blueprint for Urban Neighborhood Revival. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Hudnut, William H., III. 1998. Cities on the Rebound: A Vision for Urban America. Washington, D.C.: Urban Land Institute.

Hynde, Chrissie. 1990. “My City Was Gone.” In Learning to Crawl. CD performed by The Pretenders. Sire Records 0759923980-2. Reissued 1990.

Jensen, Brian K., and James W. Turner. 2000. “Act 77: Revenue Sharing in Allegheny County.” Government Finance Review 12: 17-21.

Joel, Billy. 1982. “Allentown.” In The Nylon Curtain, performed by Billy Joel. Columbia Records QC 38200. Vinyl recording.

Kalson, Sally. 2010, May 4. “Pittsburgh Named Most Livable City Again.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Local sec.

Kromer, John. 2010. Fixing Broken Cities: The Implementation of Urban Development Strategies. New York: Routledge.

Lange, Karen E. 2010, April. “Get the Salt Out.” National Geographic.

Lippert, John, and Jim Efstathiou, Jr. 2009, May 3. “Thirsty Las Vegas Is a Case Study of the Next Global Crisis.” Seattle Times, Business/Technology sec. http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/businesstechnology/2009164039_lasvegaswater03.html.

Lorant, Stefan. 1999. Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City. 5th ed. Pittsburgh: Esselmont Books.

Lubove, Roy. 1969. Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh. Vol. 1. Government, Business, and Environmental Change. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

———. 1996. Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh. Vol. 2. The Post-steel Era. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Mehrabian, Robert, and Thomas H. O’Brien. 1994. The Greater Pittsburgh Region: Working Together to Compete Globally. A Report for the Regional Economic Revitalization Initiative by Carnegie Mellon University and the Allegheny Conference on Community Development.

Miller, Christian, and Brian Rudick. 2007. The Pittsburgh Metropolitan Statistical Area. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. www.clevelandfed.org/research/trends/2007/0407/01regact_032607.cfm.

Miller, Harold D. 2008, April 13. “Regional Insights: What Can Keep People from Leaving Pittsburgh?” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Business sec. www.post-gazette.com/pg/08104/872629-28.stm#.

Miller-Adams, Michelle. 2009. The Kalamazoo Promise: Building Assets for Community Change. W. E. Upjohn Institute.

Müller, Rainer. 2010, April 9. “Eastern German Project Provides Hope for Shrinking Cities.” Der Spiegel. www.spiegel.de/international/germany/0,1518,688152,00.html.

Muro, Mark, Bruce Katz, Sarah Rahman, and David Warren. 2008. MetroPolicy: Shaping a New Federal Partnership for a Metropolitan Nation. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Nasaw, David. 2006. Andrew Carnegie. New York: Penguin Press.

National Resources Defense Council. 2010. Climate Change, Water, and Risk: Current Water Demands Are Not Sustainable. www.nrdc.org/globalWarming/watersustainability/files/WaterRisk.pdf.

Obama, Barack H. 2010, June 2. Remarks by the President on the Economy, Carnegie Mellon University. www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-economy-carnegie-mellon-university.

OECD. 2006. Competitive Cities in the Global Economy. Paris: OECD.

O’Neill, Brian. 2009. The Paris of Appalachia: Pittsburgh in the Twenty-First Century. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University Press.

Oswalt, Philipp, ed. 2006a. Shrinking Cities. Vol. 1. International Research. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

———, ed. 2006b. Shrinking Cities. Vol. 2. Interventions. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

Pallagst, Karina, Jasmin Aber, Ivonne Audirac, Emmanuele Cunningham-Sabot, Sylvie Fol, Christina Martinez-Fernandez, Sergio Moraes, Helen Mulligan, Jose Vargas-Hernandez, Thorsten Wiechmann, and Tong Wu. 2009. The Future of Shrinking Cities: Problems, Patterns and Strategies of Urban Transformation in a Global Context. Berkeley: Center for Global Metropolitan Studies, Institute of Urban and Regional Development, and Shrinking Cities International Research Network.

Pendall, Rolf. 2003. Sprawl without Growth: The Upstate Paradox. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

“The Pittsburgh Promise.” www.pittsburghpromise.org/.

Power of 32. www.powerof32.org/.

Rotstein, Gary. 2010, June 21. “Pittsburgh’s Population Expected to Grow in a Few Years: Region’s Exodus Finally Slowing.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Local sec. www.post-gazette.com/pg/10172/1067091-455.stm.

Sonoran Institute. 2010. Growth and Sustainability in the Las Vegas Valley. www.sonoraninstitute.org/component/docman/doc_download/878-las-vegas-report-09.html.

Springsteen, Bruce. 1982. “My Hometown.” In Born in the U.S.A. CD. Columbia Records CK 38653.

Stewman, Shelby, and Joel A. Tarr. 1982. “Four Decades of Public-Private Partnerships in Pittsburgh.” In Public-Private Partnership in American Cities: Seven Case Studies, ed. R. Scott Fosler and Renee A. Berger, 59-127. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Strategy 21: Pittsburgh/Allegheny Economic Development Strategy to Begin the 21st Century. 1985. A proposal to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania by the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University.

Toker, Franklin. 2009. Pittsburgh: A New Portrait. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

U.S. Census Bureau. 1950. Table 18. Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1950. www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/tab18.txt.

———. 1980. Table 21. Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1980. www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/tab21.txt.

———. 1995a. Arizona Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990. www.census.gov/population/cencounts/az190090.txt.

———. 1995b. Michigan Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990. www.census.gov/population/cencounts/mi190090.txt.

———. 1995c. New York Population of Counties by decennial Census: 1900 to 1990. www.census.gov/population/cencounts/ny190090.txt.

———. 1995d. Pennsylvania Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990. www.census.gov/population/cencounts/pa190090.txt.

———. 2008. Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas and Components, November 2008, with Codes. www.census.gov/population/www/metroareas/lists/2008/List1.txt.

———. 2009a. Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009. www.census.gov/popest/data/metro/totals/2009/index.html

———. 2009b. Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places over 100,000, Ranked by July 1, 2009 Population: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009. http://www.census.gov/popest/data/cities/totals/2009/index.html.

———. 2010. About Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas. www.census.gov/population/www/metroareas/aboutmetro.html.

Zlatos, Bill. 2006, June 19. Elderly Returning from Sun Belt. Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, News sec. www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/s_458636.html.