The Socioeconomic Opportunities of SynergiCity

The Promise of SynergiCity

Cities support a large number of interlinked human institutions and provide the physical context within which much of the world’s population lives and works. To support city habitation, the quality of life offered to all urban residents, regardless of their socioeconomic standing, should be a critical consideration in rethinking urban redevelopment models for the “creative age” (Florida 2002). Quality of life depends not only on opportunities to build wealth and maintain employment but also on the attributes of the built environment, measures of physical and mental health, and opportunities for education, recreation, leisure time, and a sense of social belonging (Gregory 2009). Broadly examining the SynergiCity concept allows consideration of the urban system as a whole to understand and address the complex problems many cities face, particularly declining industrial cities.

FIGURE 5.1. The Eastern Market in Detroit is a popular destination. The comprehensive redevelopment plan for the market and its surrounding district is embodied in the title “Eastern Market 360.” (Courtesy of Laura Mann)

Cities that are in physical, social, and economic decline offer fertile ground for reimagining urban form, distribution, and infrastructure, to creatively rethink and address the “wicked problems” (Rittel and Webber 1973) present in these environments. To be sure, issues of social equity, educational opportunity, and qualities of place must figure prominently in this reimagination, as should attributes of quality of life. Implementation of the SynergiCity concept in Rust Belt cities must recognize the underlying social inequity that currently undergirds postindustrial development. Likewise, addressing and strengthening the inherent qualities of place must be central in the application of the SynergiCity concept in medium-sized Midwest cities. In addressing issues of social equity in the application of the SynergiCity concept for urban redevelopment, this chapter will first briefly provide context for the idea of social equity in urban redevelopment and will then examine several ongoing redevelopment efforts that address social equity, economic opportunity, and sense of place. An analysis of efforts in two cities — Detroit’s Eastern Market District redevelopment (fig. 5.1) and Boston’s Dudley Street Initiative — offers lessons from successful bottom-up, community-based efforts that build on local strengths that can be applied to the SynergiCity concept to fully realize its potential.

The chapter concludes with three primary lessons for SynergiCity:

1. Equitable urban design and architecture. Urban redevelopment should incorporate a process that promotes involvement of all stakeholders in a meaningful way in creating the plan for redevelopment and the resulting physical interventions.

2. Safeguard the local population. It is necessary to guard against socioeconomic changes in the urban environment that result in informal eviction of lower income residents who may no longer be able to afford higher rents and decreasing affordability of local businesses as they begin to cater to a more affluent set of neighborhood consumers.

3. Environments that educate. As environments are redeveloped, they need to do more than provide for utilitarian functions. Environments should be designed so that they illustrate physically and socially sustainable development patterns. These environments may visibly demonstrate waste and water recycling or social inclusion of all generations through meaningful opportunities for involvement.

Historical Socioeconomic Patterns in the Industrial City

The social, economic, and political histories of industrial midwestern cities underlie their current physical forms. The layouts of these cities result from patterns of urbanization generated in response to the Industrial Revolution. In these cities a new social hierarchy, headed by an entrepreneurial class of industrial capitalists, developed and transformed urban physical, economic, and political structures. Patterns of socioeconomic segregation and assumptions about exploitable human labor underpinned the urban forms that these cities developed. Opportunities presented by this development came at substantial social and physical costs, as workers were forced into strictly controlled living and working conditions that were dominated by a new industrial environment. The power structures implicit in the socioeconomically segregated industrial city were exacerbated, particularly in the United States, as suburbanization resulted in ever greater distances between those in the middle and upper classes and those in the industrial working classes. Over the last three decades transformation from an industrial-based to an informational-based economy has intensified the socioeconomic divide, as well as the physical decline of many midwestern industrial cities.

The conditions of decline present in many cities are beyond singular, quick-fix solutions. Cities face complex problems resulting from a layering of decades of changing demographics, technological transformation, and a shifting and increasingly global marketplace. While the results of urban problems are visible physical decay, the threads of these problems run much deeper and are not just physical in nature. Thus purely physical solutions, while they may present a glimmer of hope as fresh, clean additions in areas of decay, ultimately fail to spark long-term and lasting change because underlying structural problems remain. The conditions present are not simply physical, not simply local, and not simply solved with more money (Keating and Krumholz 1999). They are complex, with linked social, political, economic, and physical dimensions that overlap at multiple scales. They impact not just the local neighborhoods of central cities but also adjacent neighborhoods, city districts, whole cities, regions, and states. Therefore, the solutions cannot be simple, or singular.

Some cities, such as New York, seem to be eternally resilient and able to remake themselves as a whole even while retaining pockets untouched by economic, social, and physical renaissance. Other historically industrial U.S. cities have spent decades remaking themselves and only now have begun to demonstrate progress in addressing these complex and multidimensional urban problems. Those that demonstrate success, such as Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, have built on their physical, social, and economic strengths and the opportunities they present. Rather than using public funds in public-private real estate partnerships that generate spectacular developments and provide a new highprofile façade for the downtown (Krumholz 1999), these cities have “use[d] that money to invest in local assets, spur local business formation and development, better employ local people and utilize their skills, and invest in improving quality of place” (Florida 2010: 84). Furthermore, Philadelphia, recognizing that long-term prosperity in the informational age requires an increasing population of college graduates, has taken important steps to build an alliance of city government, foundations, and private and educational institutions that support city residents returning to school to earn a degree (Florida 2010).

Even in cities and city districts that continue to struggle with complex endemic social, economic, and physical challenges, ongoing redevelopment efforts that address social equity, economic opportunity, and sense of place offer examples of successful bottom-up, community-based efforts that build on local strengths. These redevelopment efforts are offered in distinct opposition to mega real estate ventures, such as festival marketplaces and sports stadiums, which have promised comprehensive urban renaissance but mostly have provided negligible economic spillover for city residents. Efforts that have been successful in addressing the complex problems facing U.S. industrial cities as they attempt to redevelop have addressed issues of social and economic equity through local economic development that has created new jobs for unemployed local residents and provided net tax increases to cities (Krumholz 1999). Over the past 30 years, these two development paradigms — spectacular downtown real estate development and local economic development — have been deployed to address the complex challenges of urban redevelopment in U.S. cities. The two paradigms offer very different processes, as well as different physical and socioeconomic redevelopment outcomes.

Issues of Redevelopment

Planners and designers have attempted to engage urban problems throughout history. Rittel and Webber (1973) suggest that planners historically conceptualized such problems as “tame” or simple and addressed them in a straightforward manner. In addressing many urban problems of the past, this approach improved conditions for many people, for example, reducing epidemics of water and airborne disease. However, this kind of simple conceptualization of urban problems and their solutions also played a role in the complexity and intensity of urban problems that exist today. Rittel and Webber use the term “wicked” to describe the type of complex problems that planners and designers encounter in urban environments. In using this label they mean to suggest that the complexity of the problems is vexing and without a clear or easy solution. Accordingly, development of suburbs and single-use zoning has solved the problem of unhealthy urban environments by providing improved quality of life for those who could migrate to the suburbs, thus improving their condition. However demonstrating the complexity of the issue, it heightened problems for those who were left behind (Cisneros 1996).

The complicated and protracted troubles left in the wake of past planning and development efforts have stymied those who recognize their complexity (Man-Neef 1991). Several authors have suggested that viable solutions to complex problems depend on how the problem is framed (Krumholz 1999; Rittel and Webber 1973; Schon 1987). Viable solutions also are contingent on an analysis of the strengths and opportunities a particular city’s physical and social environments present. Detroit, widely recognized as one of the most economically and physically traumatized U.S. industrial cities in our day, is clearly distressed but also offers strengths and opportunities. Its current complex challenges are rooted in its historical cultural segregation and animosity between African Americans and Caucasians and the resulting race riots of 1943 and 1967; its 1970s downtown real estate development focus on the spectacular Renaissance Center; and its physical fabric of sprawling detached single-family homes developed in the age of the automobile. The historical and current strengths of the Detroit region, to name a few, include a metropolitan area population of 4.2 million, a world-class airport, the educational and research potential of two nearby major universities and numerous local educational institutions, some of the world’s most advanced engineering technology, a creative spark represented by its historical and current progressive music scene, and at present a great deal of vacant urban land (Florida 2010). Rebuilding Detroit, given its challenges and assets, will take time and creative, community-based, bottom-up development processes that must be bolstered by city and state policies that support neighborhood-based, small-scale redevelopment efforts within a frame of comprehensive regional development.

Woven through the history of Detroit, as well as other U.S. industrial cities, is the undercurrent of social inequality and social exclusion. Although Detroit had a “large and prosperous black middle class [and] higher than normal wages for unskilled black workers due to the auto industry” (Fine 1989: 32), African Americans felt dissatisfaction with Detroit’s social conditions even before the 1967 riots. They felt discriminated against in regard to policing, housing, employment, spatial segregation within the city, mistreatment by merchants, shortage of recreational facilities, quality of public education, access to medical services, and the way President Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty operated in their city (Fine 1989). Following massive white flight of the 1960s and 1970s, which hollowed out the city’s core and concentrated disadvantaged populations within the city, the conditions have continued to deteriorate, and dissatisfaction has grown as a result of ineffective redevelopment strategies. Recurrent patterns of spatial and social inequity plague many cities that have, like Detroit, chosen not to focus on their inherent strengths or to support job creation, improved education, and small-scale, residentdriven development. Even strategies that are local and neighborhood-based must be implemented carefully, lest gentrification make an area unaffordable to its low- and moderate-income residents.

Attracting middle- and upper-income households back to city neighborhoods is a common urban redevelopment strategy. Diversifying the income range of city dwellers to include households with more disposable income offers one way to maintain the economic health of cities and to increase a city’s tax base (Betancur 2002). However, this should be accomplished while securing a place for low- and moderate-income residents in their own neighborhoods. The first step in avoiding various pitfalls that isolate and exclude on the basis of social and economic characteristics is to recognize the benefit of supporting a diverse urban population. The second step is to develop a comprehensive strategy that addresses social and economic equity concerns. The next section examines two case studies that demonstrate strategies for accomplishing this second step.

Creative Economy and Social Equity

The restructuring of urban fabric that has accompanied macro-scale economic changes over the last decades of the twentieth century has exacerbated urban social inequality by creating and maintaining patterns of social and spatial exclusion. The persistence of spatial segregation, poverty, homelessness, urban crime, and neighborhood change through gentrification have been set within a debate about the “worthiness” of those who have been marginalized by these changes (Thorns 2002). Such gentrification within former warehouse and industrial districts generally follows after pioneering artists take up residence. Without specific policies and strategies to safeguard the affordability of these districts, these artists often are displaced from these districts as traditional developers use public and private funds to transform them into mixed-use villages, as Gillem and Hedrick note in chapter 7.

In order to rectify structural forces that undergird inequalities, there is a need to change the way economic and social opportunities are structured and wealth is generated (Thorns 2002). Although economic and social systems have evolved to utilize human creativity as never before, we are failing to engage the opportunity of the so-called creative age to uniformly “raise living standards, build a more humane and sustainable economy, and make our lives more complete” (Florida 2002: xiii). Rather than solving the myriad structural inequalities that exist, the creative economy has tended to amplify social and economic inequality by failing to recognize and address “externalities” (Florida 2005: 171) such as increased housing costs, economic displacement, traffic congestion, and stress. Direct confrontation of these externalities at the beginning phases of development through comprehensive planning and government support is needed. The following two case studies, Detroit’s Eastern Market District Redevelopment and Boston’s Dudley Street Initiative, highlight creative solutions that build on local strengths to recognize and address structural inequalities. The degrees to which comprehensive planning and local government support have been or could be beneficial to the bottom-up, community-based efforts will be discussed.

Case Study 1: Detroit’s Eastern Market

As noted, Detroit is widely recognized as one of the most distressed cities in the United States. Even given this notoriety, “a more organic grassroots kind of redevelopment is taking place” in Detroit (Florida 2010: 80). However, such redevelopment, “left to its own devices will neither realize the promise [of innovative, wealth-creating productivity] nor solve the myriad social problems” (Florida 2005: 171) present in a city like Detroit. This case study will highlight the redevelopment of the Eastern Market and its surrounding district to illustrate efforts to address social, spatial, and economic inequity in Detroit. This redevelopment effort, spearheaded by the Eastern-Market Board and the market’s director, builds on three of Detroit’s existing strengths: underutilized historic building stock, activist residents and nonprofit leaders, and plentiful vacant land. First, central to the plan is the Eastern Market, a public market facility that has provided city residents with access to the agricultural bounty of the region since 1891 (Johnson and Thomas 2005). Second, the plan develops linkages between the Eastern Market vendors and merchants, the city of Detroit (who owns the market’s assets), and the greater community of residents and local nonprofit organizations. Finally, the plan employs new strategies to redevelop large tracts of vacant land in neighborhoods adjacent to the market by creating a system of linked denser urban villages with networks of open space usable for agricultural production, recreation, and rebuilding a healthy urban ecosystem.

In the pre –World War II era, the Eastern Market grew to be one of the largest farmer’s markets in the United States, where fresh produce was delivered for resale to wholesalers, retailers, and the general public. However, following World War II, with the advent of prepackaged foods and the modern supermarket, the nature of the Eastern Market and the surrounding district changed. Fewer members of the general public shopped at the market, and more wholesalers and large-scale food processors located in the area. In the recent past, the Eastern Market has become known to the general public as an important hub for the southeastern Michigan food distribution industry rather than a farmer’s market serving the public throughout the week. The comprehensive redevelopment plan for the market and its surrounding district, which is embodied in the title “Eastern Market 360°,” is to transform the liveliness of Saturday morning at the market into a vitality that extends throughout the week. In addition, the overarching strategy underpinning the reinvigoration of the market and its district is to help rebuild the region’s local food system by creating facilities and strategies that help increase both the supply of and the demand for healthy food. This philosophy, related to the international “slow food” movement, links to grassroots efforts across the United States and particularly in Michigan and Wisconsin. However, the Eastern Market’s bottomup strategy to focus on developing and promoting the local food system is unique in urban redevelopment, even when compared to redevelopment in St. Louis’s Soulard Market district (fig. 5.2) where its renaissance was kindled by the return of middle and upper-income citizens in the 1970s (Rowley 2010).

FIGURE 5.2. The Soulard Square Market in St. Louis, Missouri, was founded during the 1970s and serves as a prototype for neighborhood urban markets today. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

In Detroit, this redevelopment strategy grows not only out of the desire to reinvigorate the urban environment through redevelopment but also out of a very real need for residents of the city’s neighborhoods to gain access to fresh, healthy foods in a city with a surfeit of convenience and liquor stores and without a single major grocery store (Clynes 2009). As the recession of the early twenty-first century has battered Detroit, the inability of residents to locate and afford healthy food has increased, and the goals of the Eastern Market redevelopment have solidified around strategies to increase access to healthy food while simultaneously establishing a foodcentric creative district that supports “foodie entrepreneurs” and associated startup businesses (Gentile 2009).

The Eastern Market 360° Plan is based on physical construction and reconstruction, but the purpose of the expanded and improved facilities at the market is to help redevelop Detroit’s local food system, with the Eastern Market as its hub (fig. 5.2). While the market is already part of the system’s retail, wholesale, and food processing functions, the redeveloped market will also provide nutrition education, grower training, organic waste composting facilities, specialty food production, and incubation of small food businesses (Kavanaugh 2009). Aspects of the 360° Capital Improvement Plan that specifically address social and economic equity and quality of life for Detroit’s low-, moderate-, and middle-income residents include the plan’s focus on improving public health by increasing supply and demand for nutritious food and on expanding district business activity. The plan calls for adding the Market Hall Education Center Complex and for greater utilization of the wholesale market to get food into underserved areas of the city. Thus, expanding these facilities and programs will increase access for all to knowledge about improving nutritional health and healthier cuisine and how to prepare it. Increasing district business activity includes expanding the retail farmer’s market operation beyond Saturdays, increasing special events opportunities, incubating food-related businesses, and adding appropriate mixed-use development to increase customer traffic and economic vitality (Eastern Market Corporation 2009). This goal incorporates corresponding increased opportunities for job creation and income-earning possibilities for local residents.

One other important initiative in the redevelopment of the Eastern Market campus is a partnership with the nonprofit Greening of Detroit to create the Detroit Market Garden adjacent to the campus. Detroit Market Garden will be the city’s first production-focused small-scale farm, where a variety of fruits, vegetables, and cut flowers will be grown and harvested for sale in the Eastern Market District (Eastern Market Corporation 2007). This market garden will also act as a demonstration for local low- and moderate-income gardeners to highlight intensive planting strategies and the use of hoop houses to extend Detroit’s growing season to 11 months. The garden will also produce starter plants and offer them to local gardeners. Through these strategies the market garden will facilitate more productive household and community gardens within the city, increasing low-cost access to healthy fresh food and possibly resulting in smallscale, high-yield urban farms (fig. 5.3).

FIGURE 5.3. DSI-Youth Farming Project, Detroit, August 2010. (Courtesy of Sunita L. Karan)

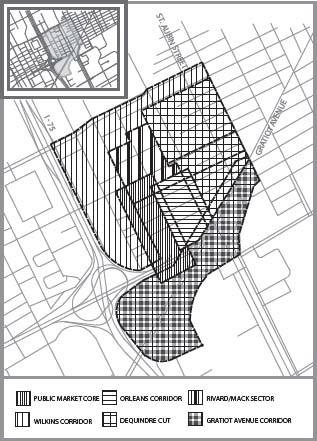

FIGURE 5.4. Map of Eastern Market District Redevelopment Area of Detroit, highlighting the six redevelopment subareas. (Courtesy of Charles Dana)

The redevelopment of the Eastern Market Campus is intended to increase the facility’s market share within the regional food network and to strengthen an important anchor that can help transform the historic core of Detroit using a food focus. The redeveloped Eastern Market Campus is the centerpiece of a plan to redevelop the Eastern Market District, an area bounded by Interstate Route 75, St. Aubin Street, and Gratiot Avenue and at this time somewhat cut off from adjacent areas (fig. 5.4). The primary initial strategy employed within the Eastern Market District Redevelopment Plan is to simplify zoning in the area; this would eliminate current conflicts between different sets of regulations and organizations such as city zoning, the Eastern Market Historic District, the Urban Renewal Area, the Empowerment Zone, and the Recreation Department Area, to name a few. This strategy would in turn lead to an increase in the area’s mix of uses and would allow greater connectivity to other neighborhoods (Kavanaugh 2009).

The proposed rezoning would eliminate purely industrial zones in favor of zones that will increase the density of business uses and expand areas devoted to residential and mixed-use residential and business. The plan seeks to balance opportunities for economic development within the district while maintaining the area’s “authentic grittiness” in order to attract more creative people to live, work, visit, and invest in the district. Further, the plan seeks to create a mixed-use, mixed-income neighborhood that improves the business climate and enlivens streets and public spaces through the careful blending of housing options and businesses that respect the “food identity” of the district. Finally, the plan seeks to enhance connectivity within the area and between it and other parts of the city so that traffic flow will be improved for vehicles, cyclists, and pedestrians and so that major corridors will develop a unique sense of place while providing pleasant experiences (Chan Krieger Sieniewicz Architecture & Urban Design 2008).

Within this comprehensive redevelopment plan the Eastern Market plays three roles: (1) the hub of a robust local food system, (2) the heart of a compelling business district, and (3) the keystone to adjacent viable and sustainable neighborhoods (Eastern Market Corporation 2009). The market also becomes the centerpiece of a socially, economically, and physically sustainable redevelopment initiative. This initiative builds on the strength of a locally diverse agricultural asset. It leverages existing facilities and infrastructure in the renovations and additions to the district. The redevelopment plan’s improved connectivity to the rest of the city through the rails-to-trails transformation that is proposed for the Dequindre Cut area, as well as the reconnecting of street grids to surrounding neighborhoods, offers the potential of easy access to jobs, food, and housing. The plan focuses on energy efficiency and small-scale energy production. It promotes the development of small, local, independently owned businesses. Addressing the fact that some city residents may have difficulty getting to the market, the plan also incorporates initiatives to bring fresh food from the market into other city neighborhoods through collaborations with local food banks and through the “AM Market Fresh Farm Stand,” which is a cooperative effort to get products from the growers at Eastern Market into a wide variety of venues throughout the region, including convenience stores in inner-city neighborhoods (Eastern Market Corporation 2009). Finally, the motivation at its heart is to improve the physical and economic health of all of Detroit’s residents.

This case study of the Eastern Market has highlighted nonprofit-driven, neighborhood-level planning and redevelopment, which has as its centerpiece a neighborhood anchor and urban historic landmark. Although the motivation for the plan is a broad concern for improving residents’ health and access to healthy food citywide, the plan relies relatively little on comprehensive city planning and policy changes. Nonetheless, it has great potential to spur new development around the market because it incorporates support for job creation through new food-based businesses with its incubator and economic development support and because it develops a mixed-use district and creates conduits to move goods from the district into the larger city. The next case study, the Dudley Street Initiative, conversely illustrates a redevelopment strategy that has been strengthened and made more effective as a result of city-level policy initiatives and changes.

Case Study 2: The Dudley Street Initiative

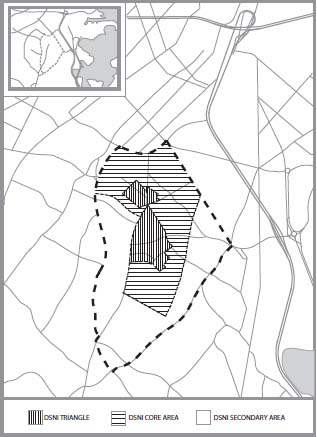

The one and a half square miles of the Dudley Street Neighborhood within the Roxbury and North Dorchester sections of Boston (fig. 5.5) had a population of 12,000 in its core area in 1990 (Medoff and Sklar 1994). While this number represents a population only half what it was in 1950, it is substantially larger than the 125 residents who currently live in Detroit’s Eastern Market Redevelopment Area. To understand redevelopment that has occurred under the Dudley Street Initiative beginning in 1984, it is necessary to take several steps back in Boston’s post–World War II development history.

FIGURE 5.5. Map of Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative Area in Boston. (Courtesy of Charles Dana)

At the end of World War II, Boston was in the midst of severe fiscal decline, with the total assessed valuation of real property having fallen about 30% between 1930 and 1960 and with only one private office building having been built in the city in that same time period. From 1950 to 1960 Boston’s population decreased by 13% as white, middle-class residents moved from the city to the suburbs. In the same decade the number of jobs in the city also declined by 10% (Krumholz and Clavel 1994). Understanding the impact of these economic conditions on their investments, business and corporate communities mobilized to elect a succession of two probusiness mayors who would be supportive of a vigorous redevelopment agenda to sustain the growth strategy of the city’s private business and real estate interests. John Hynes, mayor from 1949 to 1959, and John Collins, mayor from 1959 to 1968, successively enacted policies and redevelopment schemes that paved the way for large-scale developments like the Prudential Center and urban renewal schemes like the West End clearance project.

These efforts, dubbed the “New Boston,” exacerbated poverty by draining the city of working-class manufacturing jobs and drastically reducing the supply of housing affordable to working-class and low-income families. Fried (1972) documented the negative impact on the more than 2,600 workingclass West End families who lived in that area prior to its clearance, one of the first massive federally funded urban renewal endeavors in the country. Such large-scale “slum” clearance projects generally targeted socially cohesive working-class neighborhoods in desirable locations near downtown. Cleared land was then made ready for redevelopment by the increasingly influential business community.

During Collins’ administration, a group of particularly influential business leaders, known as the Boston Coordinating Committee, “persuaded the state and the city to create a ‘superagency,’ the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA), which combined the city’s planning and urban renewal functions” (Krumholz and Clavel 1994). The BRA’s urban renewal program cleared around 25% of the city’s land area, sharply reducing affordable rental housing. To spur development of large-scale office towers and luxury housing downtown in cleared areas, Collins offered tax concessions and other incentives. This promotion of upscale office development continued with the administration of Boston’s next mayor, Kevin White.

The pattern of redevelopment implemented in Boston between 1950 and 1984 created economic prosperity for some but left a majority of poor and working-class residents unemployed or underemployed and in competition for an ever-decreasing number of low-cost rental units in the city. These inequitable conditions paved the way for a more socially conscious political and development agenda, which many Bostonians hoped for when they elected Ray Flynn mayor in 1983. Flynn had been a progressive city council member who “was always introducing bills to protect tenants from condo conversions and rent increases” (Krumholz and Clavel 1994: 134). The Flynn agenda attempted to share prosperity between downtown businesses and the working-class and poor residents and neighborhoods through development linkage, inclusionary zoning, rent control, and control of condominium conversions.

The Flynn administration also developed a property disposition process that favored neighborhood-based non-profit development corporations (CDCs). The intention was to give neighborhood residents the ability to set the development agenda. At the same time the Flynn administration put measures in place to nurture and support development by CDCs, building development capacity, packaging available subsidies, and working to get long-term affordability guidelines in housing guaranteed by FHA, Fannie Mae, and HUD. Flynn also campaigned to get banks to invest in the city’s neighborhoods by commissioning a study of disinvestment measures among Boston’s banks (e.g., redlining, discrimination, and disparity in lending terms). The Dudley Street neighborhood and surrounding areas of Roxbury and Dorchester had suffered large-scale disinvestment during the probusiness mayoral administrations of Hynes, Collins, and White. Concurrent with the final years of the White administration and the beginning of the Flynn administration, service providers and leaders in the Dudley Street neighborhood began to meet and organize in response to negative conditions. In the midst of White’s more proneighborhood political agenda, the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative was taking shape.

The Dudley Street area was home to successive groups of immigrants who relocated from ethnic neighborhoods in the old part of Boston. From the late 1800s through the 1950s, the neighborhood sustained a mix of ethnic and immigrant groups, including Irish, Italian, and African Americans. Latinos and Cape Verdean immigrants became a significant part of the Dudley population during the 1960s and 1970s (Medoff and Sklar 1994). As a result of urban renewal “slum” clearance in some neighborhoods and gentrification in other neighborhoods, African Americans and a variety of Latino groups removed in the renewal process moved to the Dudley Street neighborhood. By 1990 the neighborhood’s population had a concentration of Latinos (30%) and of non-Hispanic blacks (50%) that included Cape Verdeans. The Latinos were a mix of Puerto Rican, Dominican, Honduran, Guatemalan, Cuban, and Mexican. The non-Hispanic black population was composed primarily of African Americans and Cape Verdeans, each making up about 25% of the Dudley core area population.

This mix of English, Spanish, and Portuguese (Cape Verdean) speakers initially came together in the 1980s around the issue of illegal dumping of garbage. Decades of disinvestment in the neighborhood, resulting from redlining by banks and insurance companies and lack of maintenance by absentee landlords, resulted in large tracts of vacant land and abandoned structures. In addition, BRA’s urban renewal plans for the neighborhood led to tensions, speculation, and one of the highest arson rates in the country (City of Boston Arson Prevention Commission 1986; Medoff and Sklar 1994). By the late 1970s, the heart of the Dudley neighborhood had “approximately 840 vacant lots covering 177 acres of land” (Medoff and Sklar 1994: 32). This desolate landscape of weedy vacant lots became a dumping ground for trash, old cars, and construction debris, resulting in unhealthy and intolerable conditions for residents. However, it took the impetus of an alliance of service providers, a private foundation, and community organizing to bring residents together to fight for residentdirected redevelopment.

In early 1981, a number of neighborhood organizations, service providers, and a church came together to form a coalition focused on neighborhood crime issues but did not generate much momentum. Later that year one of the involved groups, La Alianza Hispana, a Hispanic social service agency, commissioned an in-depth planning study by MIT students titled From the Ground Up. This document emphasized the “potential asset” in the neighborhood’s large tracts of vacant land and suggested putting vacant land in a trust for future housing and other development. In 1984, again with technical support from MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning, a strategic planning conference was organized for community stakeholders and activists. Shortly after this conference, the director of La Alianza Hispana contacted the Riley Foundation, one of Massachusetts’s larger charitable trusts, seeking funds to replace carpet in the organization’s facilities.

This initial contact was the catalyst that eventually moved Dudley community stakeholders and activists forward to organize the Dudley Advisory Group. This group set the boundaries of a Dudley Street Neighborhood core area and secondary area (fig. 5.5) and attempted to create and put a governance structure in place for what it called the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI), a coalition to build community consensus toward an overall plan of action for the core area. At a community-wide meeting to announce the formation of the coalition and ostensibly to elect board members, some of the 200 community residents who attended challenged the legitimacy of the proposed board (mainly members of the Dudley Advisory Group) because they felt that a majority of the board should be neighborhood residents. This was a turning point when neighborhood residents began to claim ownership of the renewal process in their neighborhood. Eventually a board structure was approved that included a majority of neighborhood residents.

With initial funding and assistance from the Riley Foundation, the DSNI began fervent community organizing, first around the neighborhood illegal dumping issues. Once they got action from City Hall and the mayor’s office to stop the illegal dumping, they moved on to the next issues, addressing other neighborhood quality-of-life concerns. These organizing activities also worked to unify diverse residents and neighborhood business owners, as they were brought together in the common pursuit of making the neighborhood better in the present while also creating excitement about plans for longer term renewal.

To break the pattern of outsider agency domination and to empower residents in making decisions about the redevelopment of their neighborhood, the DSNI effectively made a bargain with the city that the city would cease selling off vacant land until the people of the neighborhood were able to complete a comprehensive redevelopment plan and exercise community control over the future vision for their neighborhood (Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative 2008; Medoff and Sklar 1994). Funding from a number of philanthropic foundations, along with an impressive record of neighborhood unity and grassroots organizing victories, allowed the DSNI to hire a consultant to engage the community in a bottom-up, participatory planning process to arrive at a shared vision for the neighborhood. The city’s public facilities office somewhat reluctantly agreed to take a secondary role in this process, to make relevant data available for the planning process, and to review and evaluate existing city policy to understand what might need modification in order for the community to achieve its goals. The DSNI board worked with the planning consultant’s team to develop a vision for the neighborhood’s future and to identify neighborhood assets. The board’s vision included “low-density, mixed-income housing with owner and renter occupancy, backyards and open space; a mix of retail stores and light industry with significant local ownership; and expanded community services with particular emphasis on the youth and elderly” (Medoff and Sklar 1994: 100). A planning committee made up of residents and experienced development professionals was charged with broad development responsibility, as well as review of activities within the larger planning process. Subcommittees chaired by board members and made up of resident members of the DSNI were responsible for working with the consultants in four key areas: housing, economic development, human services, and land use/planning. Residents were primary, active participants in the planning process, which continued for nine months. The consultants worked to encourage the residents to see new opportunities in their neighborhood.

The next parts of the planning process, in mid-1987, included a series of design charrettes, in which architectural consultants and students worked with residents to translate resident descriptions into visual representations. The most significant theme that grew out of this process was the vision that continues to guide DSNI’s management of physical and social neighborhood improvements to this day. The revitalization of the Dudley Street Neighborhood into a “sustainable urban village” (Meyer et al. 2000: 1), which combines housing, shopping, open space, and a multiuse community center, guides a range of decisions about future development that will bring “not just quality affordable housing, but quality of life” to the neighborhood (Medoff and Sklar 1994: 108).

Since the completion of The Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative Revitalization Plan (DAC International 1987), many physical improvements have taken place in the neighborhood. “More than half of the original 1,300 vacant parcels have been transformed into over 454 new quality affordable homes, community centers, a Dudley Town Common, a community greenhouse, parks, playgrounds, [community] gardens, parking lots, an orchard, and allied public spaces” (Urban Strategies Council 2007). Figure 5.6 shows the formerly vacant lots that have been transformed into a community garden, as well as a renovated triple-decker, typical of housing in the neighborhood prior to redevelopment.

Many of these efforts have been completed through partnerships with other organizations that have similar goals and ideals. In keeping with the history of this grassroots movement, neighborhood residents continue to guide development through the DSNI board and committees and engage with other nonprofit and for-profit developers to complete physical improvements. Today, the DSNI primarily focuses its efforts in three areas: community economic development, resident leadership, and youth opportunities and development.

Sustainable economic development in the Dudley Street community focuses on “generating home-grown economic power” (Meyer et al. 2000: 7) via local ownership and control and local circulation of dollars engendering more living-wage jobs for residents. Continuing resident leadership necessitates efforts to cultivate leaders from among residents of the neighborhood; the DSNI believes cultivating new leaders prevents existing leaders from becoming entrenched and offers new life for the neighborhood in organizing, planning, and implementation. The DSNI's efforts focused on youth address a critical, long-term concern in the Dudley Street Neighborhood: lack of opportunities for the neighborhood’s youth to develop into the next generation of leaders. The DSNI has an extensive series of programs focused on youth development, involving efforts to support youth in organizing activities that contribute to the neighborhood, youth entrepreneurship, and postsecondary education, including the youth urban farming project developed on vacant land within the neighborhood. With its current focus on socially sustaining programs, DSNI and the Dudley Street Neighborhood are looking ahead to a promising future. Solid community organizing has built a grassroots redevelopment process that has at its heart socially equitable development outcomes that offer improved quality of life for neighborhood residents. The DSNI's efforts are particularly concerned with offering a better quality of life to the neighborhood’s low- and moderate-income, ethnically and racially diverse residents who were for so many decades treated as second-class citizens of the city of Boston.

Lesson for SynergiCity

The lessons these two case studies offer for SynergiCity are as much about process as product; they both describe processes and outcomes that are more equitable than what has become business as usual in the redevelopment of many cities in the United States. These efforts illustrate redevelopment initiated by a nonprofit entity in the case of Eastern Market in Detroit and citizeninitiated redevelopment in the case of the DSNI in the greater Boston area. In both cases, the initiators had something other than financial profit as the primary motivator. And because they have controlled the process, they have been able to maintain focus on socially equitable outcomes, even as they have engaged, or may in the future engage, for-profit developers to take on pieces of the larger plan. While these two efforts are not primarily motivated by financial gain, we can draw three important lessons from them that can be applied to any redevelopment effort, whether for-profit or nonprofit, to create more socially equitable processes and products that offer new economic viability for urban neighborhoods and their residents.

FIGURE 5.6. The Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative Revitalization Plan in Boston has transformed formerly vacant lots into community gardens and spearheaded renovation of existing multifamily housing in the neighborhood. (Courtesy of Sunita L. Karan)

PROMOTE EQUITABLE URBAN DESIGN AND ARCHITECTURE

The first lesson offered for SynergiCity is the need for a process that involves all stakeholders in a meaningful way in creating the plan for redevelopment and the resulting physical interventions. The professionals involved in this process must work to move resources, political power, and political participation away from business elites who have frequently benefited from public policy and redevelopment and toward the needs of middle, moderate- and low-income people (Krumholz and Clavel 1994), who are often deprived of basic quality of life by redevelopment. Illustrating such a reversal of process and product, the DSNI case study describes what was considered a “throwaway” in the city of Boston in the late 1970s. The BRA was preparing to bulldoze sections of an urban neighborhood that was home to more than 12,000 people without regard for the needs or desires of those people or consideration of what would happen to them if their neighborhood was cleared.

Boston mayors and city council members listened and responded to powerful business interests in the city at the expense of working-class and low-income city residents, who were denied a voice and were left in ever more perilous economic, social, and physical conditions. The first lesson for SynergiCity should be incorporating a process and products that could be characterized as Equitable Urban Design and Architecture. It is more inclusive of diverse voices and offers the opportunity to tap the creative potential of the two-thirds of the workforce who are currently outside the creative sector (Florida 2005) by bringing them into the process of redevelopment. This lesson opens redevelopment to organic, bottom-up, community-based efforts. These efforts must be supported by local government policies and processes, as the Dudley Street case shows. But it also can be facilitated by university-based community design efforts in partnership with resident- and nonprofit-led efforts. Some for-profit developers are making an effort to involve local residents in development decisions. However, unless local citizens see themselves as partners, they will most likely not view such efforts as equitable.

SAFEGUARD THE LOCAL POPULATION

The second lesson responds to Florida’s concern for the “externalities of the creative age” (Florida 2005: 171). As a city works to create the environment that will attract creative workers and as a consequence attract companies involved in the creative economy, it may prompt gentrification as an area becomes more desirable. When wealthier people buy property in a less-prosperous community, the average income increases and average family size decreases. Gentrification may reduce industrial land use when an area is redeveloped for commerce and housing, as the Eastern Market Redevelopment case study illustrates. The gradual transformation of industrial buildings to mixed-use residential and commercial can reduce available industrial, living-wage jobs. Gentrification of areas as a result of redevelopment also often results in the informal economic eviction of lower-income residents, because of increased rents, house prices, and property costs. Such socioeconomic changes often spawn new local businesses that cater to a more affluent base of consumers and decrease affordability of goods and services for less wealthy residents.

While it can be desirable to attract a more economically diverse population to neighborhoods through the redevelopment process, if the promise of the creative age is to be realized, no one can be left unconsidered or suffering negatively through the redevelopment process. The lesson about safeguarding the local population suggests that the SynergiCity concept must incorporate, among other things, the means to support a diverse series of affordable housing options. This can be accomplished, as the Dudley Street case shows, through linkage and inclusionary zoning policies and support for neighborhood-based CDCs through local policy initiatives, and through the deliberate inclusion of housing choices that will appeal to a diverse socioeconomic population. In the case of the DSNI, the resident-directed nonprofit development corporation was one important vehicle for the development of an appropriate array of affordable housing choices. Likewise, the support of several philanthropic foundations was critical to maintaining housing affordability and promoting appropriate economic development for the neighborhood, the other component that must be considered. Economic development that creates new jobs for the local population and provides a net tax increase to support basic infrastructure and services is a critical component to safeguard the quality of life of the local population. Development incentives must be carefully structured so that they do not relinquish tax revenues that are greatly needed to support city infrastructure and services (e.g., fire, police) and public goods like financially sound public education systems.

CREATE ENVIRONMENTS THAT EDUCATE

The final lesson that these case studies offer for the SynergiCity concept has to do with the need for redeveloped environments to do more than provide for utilitarian functions. Both case studies feature physical and social environments that educate present and future generations about ways to reverse the negative consequences of current development patterns. The Eastern Market offers components of the physical environment that educate local urban gardeners about intensive planting techniques, methods to extend the local growing season, and organic waste composting — all means to increase garden yield for households, often of limited means, that will benefit from greater access to healthy food that they grow themselves. The Eastern Market likewise demonstrates an environment that intends to produce 15% of its energy from renewable sources (solar panels and biogas generation) and to increase comfort while reducing energy needs by introducing passive heating and cooling schemes. The Eastern Market development also offers more traditional learning environments such as classrooms and teaching kitchens that will be used to educate local residents about nutritious foods and how to prepare them.

The DSNI illustrates a social environment that educates neighborhood residents, and youth particularly, about their talents as leaders and their value within the neighborhood social network. The DSNI's programs to foster resident leadership in adults and youth demonstrate to residents their worth in the community. This is critical to community participation and contradicts many messages that low-income minority adults and youth receive from the broader social environment about their lack of value vis-à-vis middle- and upper-income urban area residents. Like the Eastern Market, the DSNI also provides support for more traditional forms of education through its youth scholarship program and the neighborhood mentoring activities of those youth who are scholarship recipients. The Dudley Street Neighborhood redevelopment likewise also includes aspects of the physical environment that educate with regard to equitable and resource efficient development through reuse of existing housing and additions of new affordable housing and through the local urban farms and community gardens that now exist on vacant land in the neighborhood. These aspects demonstrate careful and equitable use of resources that benefit low- and moderate-income residents by supporting basic needs for a healthy living environment.

The planners, architects, and landscape architects who work on this kind of development effort must conceive of environments, like those presented here, that not only amply satisfy functional needs but go beyond them to educate all who experience the environment about development options that have a smaller resource footprint and promote an equitable social arrangement.

The Socioeconomic Opportunities of SynergiCity

This chapter has demonstrated that with some very deliberate efforts, the SynergiCity concept offers incredible socioeconomic opportunities for cities and the broad social and economic spectrum of urban residents. As Florida (2002: xiii) points out, no one is going to succeed in modifying the social and economic system “to complete the transformation to a society that taps and rewards our full creative potential” without taking careful and deliberate actions that target the entire population. Such a modified social and economic system will need to recognize the worth and potential contribution of all citizens. It will need to nurture the potential contributions of those who are not yet part of the “creative class.” Conditions to nurture creative contributions will require that planners, policymakers, politicians, educators, architects, urban designers, and developers come to terms with embedded structural inequalities and work to reverse those inequalities through changes in public policy, education, and the built environment. With such changes in place, the socioeconomic promise of SynergiCity can be broadly realized.

References

Betancur, J. J. 2002. “Can Gentrification Save Detroit? Definition and Experiences from Chicago.” Journal of Law in Society 4(1): 1-12.

Chan Krieger Sieniewicz Architecture & Urban Design. 2008. Eastern Market District Economic Development Strategy. Cambridge, MA: Eastern Market Corporation.

Cisneros, H. G. 1996, December. “The University and the Urban Challenge.” In A Collection of Essays. Special issue, Cityscape 1-4: 1-23.

City of Boston Arson Prevention Commission. 1986. Report to the BRA on the Status of Arson in Dudley Square. Boston: Boston Redevelopment Authority.

Clynes, M. 2009. “Fresh, Fresh, Exciting: Near East Side Dwellers Get Boxes of Green Goodness.” Available at the website of Issue Media Group, www.modeldmedia.com/features/freshfood20209.aspx. Accessed February 8, 2010.

DAC International. 1987. The Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative Revitalization Plan. Boston: DSNI.

Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative. 2008. “DSNI Historic Timeline.” Available at the website of Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative’ www.dsni.org/timeline.shtml.date. Accessed June 10, 2010.

Eastern Market Corporation. 2007. “Detroit Eastern Market.”

———. 2009. “Eastern Market: Redeveloping America’s Largest Public Market.” Detroit: Eastern Market Corporation.

Fine, S. 1989. Violence in the Model City. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Florida, R. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic Books.

———. 2005. Cities and the Creative Class. New York: Routledge.

———. 2010. The Great Reset: How New Ways of Living and Working Drive Post-crash Prosperity. New York: HarperCollins.

Fried, M. 1972. “Grieving for a Lost Home.” In People and Buildings, ed. R. Gutman, 229-48. New York: Basic Books.

Gentile, M. 2009. “Saturday Morning Marketing: Entrepreneurs Use Eastern Market to Grow.” Available at the website of Issue Media Group, www.modeldmedia.com/features/easternmarket20209.aspx. Accessed February 8, 2010.

Gregory, D. 2009. “Quality of Life.” In The Dictionary of Human Geography, ed. D. Gregory, R. Johnston, and G. Pratt, 606-7. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Johnson, L., and M. Thomas. 2005. Detroit’s Eastern Market: A Farmers Market Shopping and Cooking Guide. 2nd ed. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Kavanaugh, K. B. 2009, March 17. “Eastern Market Plan Calls for $50M in Investment over 10 Years.” Model D, Development News sec., www.modeldmedia.com/devnews/emkt36018309.aspx.

Keating, W. D., and N. Krumholz, eds. 1999. Rebuilding Urban Neighborhoods: Achievements, Opportunities, and Limits. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Krumholz, N. 1999. “Equitable Approaches to Local Economic Development.” Policy Studies Journal 27(1): 83-95.

Krumholz, N., and P. Clavel. 1994. Reinventing Cities: Equity Planners Tell Their Stories. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Man-Neef, M. A. 1991. Human Scale Development: Conceptions, Applications and Further Reflections. New York: Apex Press.

Medoff, P., and H. Sklar. 1994. Streets of Hope: The Fall and Rise of an Urban Neighborhood. Boston: South End Press.

Meyer, D. A., J. L. Blake, H. Caine, and B. W. Pryor. 2000. Program Profile: Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative. Columbia, MD: Enterprise Foundation. Rittel, H. W. J., and M. M. Webber. 1973. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences 4: 155-69.

Schon, D. A. 1987. Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Thorns, D. C. 2002. The Transformation of Cities: Urban Theory and Urban Life. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Urban Strategies Council. 2007. “Boston’s Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative and Dudley Neighbors, Inc.” Unpublished summary.

Urban Strategies Council. Available at www.urbanstrategies.org/programs/econopp/slfp/documents/DSNIDNIDesc507.doc. Accessed January 6, 2012.