Creating a Town-Gown Partnership

THE MILWAU KEE MODEL

Many factors must converce to successfully stimulate the growth and reinvention of cities, and as many agents of creative change as possible need to be harnessed toward the positive regeneration of the urban environment. One such agent, which can often be overlooked in the municipal decisionmaking process, is that of education, specifically higher education, for universities and colleges can provide a continuous stream of fresh, new ideas and alternatives that can enrich the debate on future development. Faculty and students, particularly in design-related disciplines, can focus their intellectual exploration on city issues and help to inform and influence physical change. However, their efforts can only be effective if their work reaches the appropriate level of political decisionmaking and, as important, if they can do this on a regular basis. Without this consistent engagement good ideas, whether potentially useful or not, will remain untested in the realm of theory. In order to promote a more effective engagement between academic exploration and practical development, a formal, structural relationship can promote the chances of new ideas being introduced at the appropriate political level and increase their capacity for contributing toward positive regeneration.

In Milwaukee, an innovative partnership between city government and a major public university has been developed to explore the role education can play in “real-world” urban development. Now in its sixth year, the “town-gown” initiative structurally links the vision, energy, and diverse abilities of the faculty and students of the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee (UWM) School of Architecture and Urban Planning (SARUP) with the ongoing infrastructure needs and interests of the city of Milwaukee. Through the direct engagement of the school in city development on a daily basis, faculty and student perspectives are introduced into the routine activities and awareness of the city. In addition, regular coordination of semester courses, studios, and theses in both academic departments with prevailing governmental interests and initiatives enables the exploration of a continuous stream of focused ideas and to their ultimately being shared with city personnel, enhancing the potential for positive change.

This chapter will articulate the nature of the partnership that has been forged between the city of Milwaukee and SARUP. The mutually established agenda will be examined to assess its impact after six years, and lessons learned from the experience will be outlined as a potential blueprint for other communities where a relationship between city government and local universities could be similarly beneficial. This includes enriching the academic experience for students with real-world projects, engaging faculty in applied research opportunities, and injecting fresh, innovative ideas into governmental departments responsible for urban redevelopment.

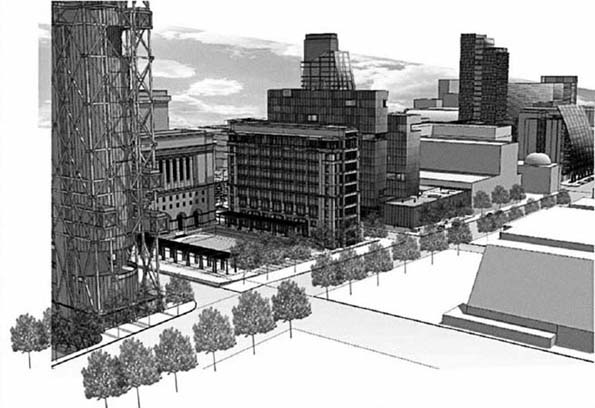

FIGURE 11.1. Aerial view of the now demolished Park East Freeway in Milwaukee. The combined efforts of the city of Milwaukee working in partnership with the School of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee convinced planning officials that the freeway should be removed and the Park East corridor should be redeveloped instead with mixed-use buildings. (Courtesy of the City of Milwaukee Department of City Development)

The School of Architecture and Urban Planning: The Urban Focus

Since its inception 40 years ago, SARUP has always been mindful of its urban context and has tried to be a relevant agent for change and influence within the city of Milwaukee. Certainly, there has been a long history of involvement that has led to significant redevelopment. Projects that were initially explored in the 1980s and 1990s in design studios or as special projects and that ultimately came to fruition include O’Donnell Plaza (a public plaza built on a parking garage at the lakefront), the Public Market, East Pointe Commons, and the removal of the Park East Freeway (fig. 11.1).

During the tenure of Mayor John Norquist, the city raised urban design in Milwaukee to greater significance, and the relationship between SARUP and the city began to formalize. Both the mayor and his director of planning taught as adjunct faculty at UWM, and the dean of SARUP chaired the City Plan Commission during the 1990s at the mayor’s request. A number of faculty members also served on related city committees and task forces (for example, the Historic Preservation Commission). At the same time, as the program matured, SARUP evolved into a significant influence in Milwaukee architecture and planning. For example, the skyline of the city has been effectively shaped by the many alumni (and faculty) who work in local practices, while the architect selection process for major projects invariably involves SARUP influence, most notably in the cases of Discovery World, the Public Market (fig. 11.2), the Bradley Technical School, the Milwaukee Theatre, and the extension to the Milwaukee Art Museum. However, the relationship between town and gown, while often useful, was predicated on a project-by-project basis, so interaction was not always as consistent or information sharing as effective as some believed it could be.

With the election of Tom Barrett as the new mayor of Milwaukee in 2004, a new opportunity arose to create a more formalized relationship between academia and government. After considerable discussion, the city appointed the dean of SARUP concurrently to the position of director of planning and design for the city of Milwaukee, thereby creating a new structural link that brought the ideas and viewpoints of the SARUP directly into the Department of City Development (DCD) and the mayor’s office on a regular basis. These partnerships have resulted in an increase in student and faculty involvement in city planning and design, an intensified coordination of city interests and needs with student course and studio direction, and the exposure of governmental decision-makers to a wider variety of design-related ideas. As faculty and students have engaged directly in city projects, city staff have become more regularly involved in teaching classes and attending design juries at the university, thus simultaneously enriching the academic process.

Formulating the Agenda

While creating a structural link through a formalized, contractual relationship was at the heart of the initiative, the intent was not to transform the university into a quasi-governmental unit performing routine duties. Initial discussions led to the development of an overarching strategy that has directed the work completed over the past six years. Influenced by the thinking of Allison and Peterson Smithson, English visionary architects of the mid-twentieth century, early presentations of the initiative likened the arrangement of streets and buildings within the city to the intricate weaving of fabric, most specifically the fabric contained within a single valuable entity like a tapestry or carpet. While this did perhaps on occasion engender some bafflement and amusement among city personnel, it was effective in highlighting two maxims derived from the metaphor that have driven efforts ever since:

Everything is Important.

The Whole must exceed the sum of the Parts.

The notion of conceiving all 99 acres of the city as a single entity has helped to articulate the position that all areas of the city are important, from the downtown to the furthest southern neighborhoods, and that all parts of the urban fabric — buildings, streets, alleys, parking lots, parks — have to work in harmony to enhance urban quality. Furthermore, it is important to convey that all buildings matter, regardless of size and function. While big, prominent iconic structures are important, the less glamorous building stock — big box retail, parking garages, signage, strip malls, and so on — still have a powerful and sometimes deleterious impact on urban quality and are deserving of equal attention from the city. (Of course, these principles were not entirely new to city planning, as evidenced by the success of the Riverwalk development along the Milwaukee River under Mayor John Norquist and in recent area planning efforts, such as the Third Ward Plan, adopted in 2005.)

From this early strategic thinking, a three-part agenda was developed, as follows.

FINISH THE PLAN

Since its incorporation in 1846, Milwaukee has never undertaken comprehensive citywide planning. It certainly undertook some excellent planning that has been very effective — for example, the Menomonee Valley Plan and the 1999 Downtown Plan — but the plans tended to be localized, discrete, unrelated to each other, and predominantly clustered around the downtown.

Based on the success of several Area Plan exercises that engaged local organizations, businesses, and individuals in the planning process, the DCD Planning Department launched an ambitious initiative to complete all planning for the city of Milwaukee within five years, including a Comprehensive (Smart Growth) Plan and 12 Area Plans (two of which were updates of existing plans) that collectively covered every part of the municipality. Given the considerable expense to the taxpayer of this extensive venture, the department pledged to reduce the anticipated cost of each plan by bringing work normally contracted out to consultants in-house. (The initial plan costs were estimated at $200,000–$250,000. The DCD Planning Department calculated that they could work efficiently with consultants and reduce the cost per plan to $150,000.) In each case, only half of the plan cost was requested from the city and ultimately the taxpayer. The DCD Planning Department agreed, in an unprecedented move, to privately raise the other half of the funding from grants and private donations between 2005 and 2009 — despite the challenge of adopting the new role of fundraiser. (The Department personnel successfully raised the matching funds necessary to complete all the plans and even extended their work by agreeing to update the 1999 Downtown Plan.)

At the time of writing, all Area Plans and the Comprehensive Plan have been fully funded, completed, and approved. The original 1990 Downtown Plan has also been updated and awaits imminent approval from the city, and work has also been completed on the Mayor’s Green Team report, which entailed considerable contributions from UWM faculty and students and has led to the establishment of the Office of Sustainability within the mayor’s office. The overall exercise has engaged countless organizations, businesses, community groups, and individuals from across the city, empowering them to participate in the visualization of their future. The power of the planning process and the engagement of so many citizens have already led to actions both predictable and unforeseen, such as the successful securing of development grants, the creation of new business organizations, including the Airport Gateway Association, and the creation of neighborhood amenities such as parks.

FIGURE 11.2. The Milwaukee Public Market in the Third Ward. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

FIGURE 11.3. Addition to Eero Saarinen’s Milwaukee Art Museum by Santiago Calatrava. The sculptural brise-soleil opens and closes like the wings of a bird to regulate light entering the interior atrium. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

RAISE THE BAR

In 2001, the extension of the Milwaukee Art Museum, by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, was completed (fig. 11.3). This proved to be a catalytic event in Milwaukee, helping to raise public awareness and expectations for future development. This phenomenon, coupled with mayoral support from two administrations, a regular, persuasive voice of architectural review in the local newspaper, and the growing influence of SARUP, led to the formation of the Design Review Team within the DCD. The stated purpose of the Design Review Team has always been to consistently raise the bar on Milwaukee architecture by working collaboratively with architects and developers. Members of the team, who are comprised almost entirely of architecturally trained UWM alumni and interns who work in the DCD, review all projects that require any form of city subsidy or approval. Commentary to applicants is confidential and, wherever possible, constructive, in an attempt to, at a minimum, make every project, however modest, a little better than it might have been. Major successes include the Intermodal Station, certain big box developments (a seven-part set of guidelines has been developed), bridges, parking lots, garages, and even signage: the maxim “Everything is Important” underlies all activities.

THINK OUTSIDE THE BOX

While the strength of the academic role lies primarily in the development of new ideas that inform the decision-making process in the physical environment, faculty and students play an expanded role in neighborhood development, many of them through Community Design Solutions (the outreach arm of SARUP, which completes over 20 projects a year), and work directly with city agencies and numerous community groups and businesses (see appendix A).

However, an added strength of the academic world lies in its role as “idea factory” — the promulgation of alternative futures that require out-of–the-box thinking initially freed from political and financial constraints. The SARUP has had significant success in this role. For example, under the direction of former planning director Peter Park, SARUP successfully explored the demolition of an infrequently used and aging freeway, creating plans for redevelopment as a reweaving of the urban fabric that was displaced by its original construction. The plans were met with interest, the ideas were adopted by the city, and the freeway has now been razed. The area awaits development; many plans created within the redevelopment area have been temporarily deferred due to prevailing economic conditions. Looking at politically charged projects such as knocking down a freeway (the demolition was completed by April 2003) from an academic perspective effectively insulates government from attack, as the work remains within the academic arena and at a theoretical level. Should the ideas find favor in the public realm, however, they can be speedily adopted and adapted for municipal use.

Another such project that the current mayor requested students and faculty to address concerned the future of MacArthur Square, a sprawling, illused park disconnected from the grid of the city, sitting atop a 2,000-space underground parking garage exhibiting significant signs of wear and water damage.

It was estimated that over $20 million worth of reconstruction would be necessary solely to fix the leaks, while the parking garage would remain as isolated and underutilized as ever. What could be done, if anything, to address this problem that had been ignored or overlooked for many years?

Under the visionary guidance of SARUP professor Larry Witzling and with strong support from DCD commissioner Richard “Rocky” Marcoux, a scheme was developed that effectively reconnected the raised park to the city grid, thereby allowing vehicle access, by bringing two ramps up onto the surface of the park. This then opened up hitherto unrecognized development opportunities, which were visualized by local architectural practices in a two-day charrette, funded by a local philanthropic group, the Herzfeld Foundation (fig. 11.4).

While economic uncertainty has stalled plans for repair and therefore major redevelopment of the square, the radical thinking in the plans will provide a provocative perspective on redevelopment that will shape planning decisions at the appropriate time.

Summary

The structure of city government differs considerably from that of an academic department, and while their objectives may differ, it is possible to link them in a way that benefits both agendas. The structural linking of SARUP with DCD ensures continuous dialogue between the two entities, primarily hinged around the joint appointment of the dean/director of planning and design (now the chair of DCD). This has led to greater coordination of class and studio projects with city interests, the results of which are collectively presented to government officials each year in an archival publication, SARUP in the City (see appendix B). In addition to the approximately 25 projects and 15 theses that are focused on Milwaukee each year, Community Design Solutions often undertakes as many as a further 20 projects that are directed toward neighborhood redevelopment. The structural link also ensures a two-way transfer of personnel between the institutions. There are a number of interns working in the city, and DCD planning personnel, as noted, often teach or participate in classes and studios.

As an urban institution, SARUP has a responsibility to respond to its immediate environment and do whatever it can to be a force for positive change. The creation of a formal relationship with an enlightened city government ensures ongoing dialogue and the flow of new ideas and perspectives directly to the decision-making levels of government. This enables the city to be enriched and informed by its academic partners and the students and faculty to become a relevant force for renewal in their environment, thus enriching their professional development. While this model may not be appropriate to all schools or cities, the benefits of a win-win partnership are worthy of exploration by the academy and government alike in all cities that could benefit from similar partnerships.

FIGURE 11.4. Artist’s rendering of proposed redevelopment of Kilbourn Avenue and MacArthur Square around the County Courthouse in Milwaukee. Town-gown partnerships can yield powerful and innovative solutions when civic leaders, city planners, and academic partners share a unified vision. (Courtesy of the City of Milwaukee Department of City Development)

COMMUNITY DESIGN SOLUTIONS PROJECT LIST, SUMMER 2008–SUMMER 2010

Planning and design

Source: Compiled by Susan Wei strop, Community Design Solutions coordinator

MILWAUKEE-FOCUSED COURSEWORK, STUDIO WORK, AND THESES PUBLISHED IN SARUP IN THE CITY, ACADEMIC YEAR 2009-2010

Coursework, Department of Urban Planning

Riverworks Neighborhood Indicators

The Zilber Institute

The Solar Initiative

The Hoan Bridge

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Campus Plan

WIRED R

The Milwaukee Foreclosure Crisis

Riverwest Neighborhood Plan

Village of Wauwatosa Business Improvement

District

Transit in Milwaukee

Brown Deer Road Corridor Redevelopment

Kinnickinnic River Parkway

Public Participation Plan

M. Arch. Theses, Department of Architecture

The Residential Alley

Popular Houses of West Allis

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Catholic

Student Center

St. Francis Cousins Center

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Residence Hall

The Loyalty Building

Interconnectivity — Space in the City

Urban Energy Center

Milwaukee Intermodal System

Sofi Urban Spiritual Retreat

The Urban Dance Center

Oak Leaf Trail Center

Family Co-housing in Downtown Milwaukee

Milwaukee Industrial Museum Reed Street Yards

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Daylight Institute