Peoria’s Warehouse District

CHALLENGES FOR DEVELOPMENT

Most people are not aware that peoria was a bustling, prosperous regional center for territorial trade, transportation, and commerce long before Chicago (Fort Dearborn) was much of a settlement on the banks of Lake Michigan. Peoria’s location on the Illinois River and within the fertile central Illinois prairie has been a positive factor in its development and growth throughout its history (fig. 12.1). Its natural resources of freshwater for drinking and transportation and rich, productive soils for agriculture have attracted resident entrepreneurs and many others who have capitalized on these and other resources offered by the region.

Like Peoria, many communities have experienced the economic transitions from an agrarian base to manufacturing and, now, to the information age. The ebb and flow of these transformations have certainly been evident in Peoria, from its earliest history, when the riverboat packet companies hauled freight up and down the Illinois River, to the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the distilleries that formed the Warehouse District and, more recently, as the world headquarters of Caterpillar, the world’s largest manufacturer of earth-moving equipment. The economic legacies of these historic enterprises are evident today — not the least of which is the built environment of substantial warehouses and commercial structures located in the community’s former rivercentric warehouse district. This chapter will explore the issues, challenges, and opportunities involved in the reinvigoration of this important area within Peoria.

The “Rest” of Illinois: Beyond Metropolitan Chicago

“Just outside Chicago, there’s a place called Illinois.” The state of Illinois developed this catchy slogan for its tourism marketing program to encourage Chicago-area residents to visit Illinois south and west of Chicago, instead of visiting Wisconsin and Michigan. The strategy is aimed to keep tourism and the dollars it generates in Illinois.

The strategy need not stop at tourism, though. Communities in downstate Illinois, like Peoria, should employ a similar strategy when attracting businesses and economic development. Attractive “assets” abound. Outside of the Chicago metropolitan area, the cost of home ownership and renting, as well as, generally, the cost of doing business, is much lower. Congestion, often cited as a quality-of-life issue, is virtually nonexistent; “rush hour” in smaller communities is often the “rush minute.”

Demographic trends indicate that the challenges are only going to increase for northeastern Illinois. By 2030, the state is projected to grow over 15%, but of the 2 million more people who will live there, most will be living in or near metro Chicago. While growth is encouraging, it comes with associated costs. Both Chicago and Illinois would be better off if some of the projected growth occurred in other Illinois communities.

Illinois communities outside the greater Chicago metropolitan area, and Peoria in particular, could accommodate and welcome much of this projected new growth. Many communities are at best experiencing moderate growth, while many more are losing population. These smaller communities often have housing stock, roads, schools, and other infrastructure that have greater capacity than they need to meet their present and future needs.

This potential is illustrated by comparing two large metropolitan areas in Illinois. The moderately growing Peoria metropolitan area is the second largest metro area in Illinois. However, as a quality-of-life comparison between Peoria and Chicago illustrates, there are significant advantages to locating or relocating “downstate” in Illinois (table 12.1).

Relocating Businesses and Employees Downstate

Before the Great Recession of 2008–2009, more people were able to determine where they would work in the United States. Today, the internet permits people to work remotely. Telecommuting allows mobile professionals to flee large, congested metro areas and work and live in less congested cities or even rural environments. Freelance writers, advertising executives, entrepreneurs, artists, computer experts, and salespeople are typical employees and entrepreneurs who often have control of their work location. Jack Manahan is a government computer consultant who left the Chicago suburbs for Peoria. When he needs to visit a client, he simply drives 10 minutes to the airport. “I saved half the cost of my auto insurance and got a much nicer home in Peoria when I left Chicago,” says Manahan. “And the rush hour is much less than in Chicago. Peoria is a pleasant place to live and work, without the hassle of a really big city.”

Manufacturers, agencies, sales forces, and consulting companies no longer need to be located in a large metropolitan area to conduct business, with modern communications technologies and globally connected transportation hubs conveniently located to regional business areas. The same connectivity that permits telecommuting allows business leaders the flexibility to move their entire companies to smaller, more attractive communities where both the quality of life and the cost of doing business can be better. This trend is accelerating and will likely continue to be popular, especially as big city congestion increases.

Peoria’s Warehouse District Strategy circa 2006

Peoria is the city center for the second largest metropolitan area in Illinois and boasts the second most intensely developed downtown. The downtown is a vibrant and successful commercial district with an attractively redeveloped riverfront, beautiful buildings, and, until recently, a strong and growing employment base. Like many older cities, however, it is in need of new housing and retail in and near the downtown core. The city has many historic industrial buildings that could be adaptively reused as housing and retail space. Some vacant tracts could welcome new construction of single-family homes and townhouses.

Figure 12.1. Peoria in the early twentieth century. Peoria’s growth throughout its history was due to its access to the Illinois River. (Courtesy of Peoria County Historical Society)

TABLE 12.1 Chicago and Peoria: Quality-of-Life Comparisons

| CHICAGO | PEORIA | |

| Median home price 2006–20101 | $269,000 | $119,000 |

| Average commute time (2006–10)2 | 34 minutes | 17 minutes |

| “Cost of doing business” rank3 | 90th | 47th |

| Cost-of-living index composite4 | 103.9 | 96.9 |

| Student/teacher ratio5 | 16.4 | 14.4 |

Source: Courtesy of Chris Setti, Ray Lees and Craig Hullinger.

1“U.S. Census Bureau 2006-2010.” http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/17/1714000.html

2“U.S. Census Bureau 2006-2010” http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/17/1714000.html

3“Best Places for Business and Careers,” Forbes, May 5, 2005.

4Cost of Living Index, 2nd Quarter 2005, Council for Community and Economic Research, http://www.coli.org/store.asp. Accessed January 6, 2012.

5“Best Places to Live 2005” CNN Money, http://money.cnn.com/magazines/moneymag/bplive/2005/index.html. Accessed January 6, 2012.

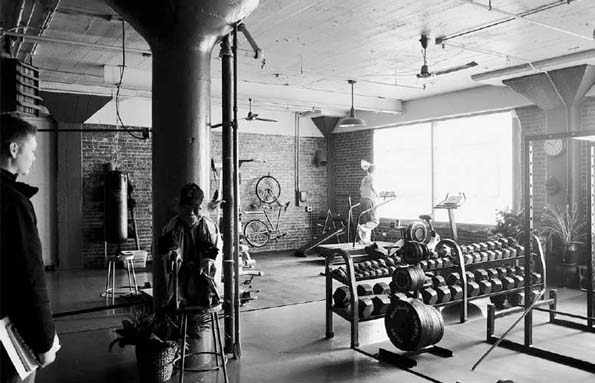

FIGURE 12.2. The fitness room in the Murray Building in the Warehouse District of Peoria allows tenants to stay in shape. With over 80,000 gross square feet of space, the Murray Building illustrates the potential of adapting warehouses for almost any use. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

The formally designated Warehouse District, located immediately south of downtown Peoria on the Illinois River, has great redevelopment potential. Many well-constructed and structurally sound masonry buildings constructed in the late 1800s and early 1900s are located in the district, as are one-story industrial buildings of more recent vintage, along with many vacant land parcels. While many of these buildings are in good condition and some have been adapted to new uses today, the economic value of many of the historic multistory buildings located in the district had greatly diminished by 1980. During the 1960s and 1970s many industrial and warehousing operations were relocated to modern one-story buildings in other areas of the city or suburbs, which left many of the buildings to be mothballed or barely maintained, while others were abandoned and, regrettably, allowed to deteriorate to the point that demolition was required.

As the proposals for a SynergiCity approach to this area have already shown, it could once again become a vibrant urban neighborhood with a mix of residential and commercial uses. Examples of the adaptive reuse of the old industrial lofts already exist on Water Street between State and Liberty streets. Street-level space makes prime commercial and retail uses, and upper floors can be occupied by offices and residences. Artists and artisans have already relocated to the district, leasing studios primarily in former warehouse buildings such as the Murray Building (fig. 12.2).

Recognizing the economic value of this historic building stock and the proximity of the Warehouse District to the city center and Central Business District, the city of Peoria has formulated a Redevelopment Strategy to promote the revitalization of this area into a new urban community.

To more effectively assess and plan for the Warehouse District’s revitalization, the city has supported a wide variety of initiatives and studies, including developing a Comprehensive Plan and conducting a Detailed Building Inventory. This was followed by the planning guidelines and recommendations published in Heart of Peoria, the result of a community charrette led by Andres Duany of DPZ Architects in 2003. The city of Peoria then commissioned the Warehouse District Redevelopment Plan and TIF Study, which recommended creating Tax Increment Financing (TIF) zones throughout the city to encourage development. Heart of Peoria had recommended using a form-based code to promote a mix of uses based on market research conducted by the focus group Ferrill Madden and Tracy Cross.

FIGURE 12.3. The adaptive reuse of 401 Water Street for prime office space illustrates the potential of historic warehouses to meet modern living and working requirements. Renovation of existing buildings is often cost effective; the average purchase price may be less than $11 per square foot, and retrofit can cost as little as $40 per square foot. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

Public-Private Collaboration: A Key to Success

Each of the community stakeholders knows that the long-term success of redevelopment is dependent on both the city and the private sector coming together and working collaboratively to achieve common goals and objectives. A few of the “action” items expected to be accomplished by developers and the city include Developer Actions and City Actions.

Developer Actions include (1) acquiring or optioning for developable real estate for new buildings in the district, (2) renovating existing buildings for mixed uses, (3) implementing the Heart of Peoria Plan using Smart Growth planning, (4) market redeveloped buildings to a wide range of buyers or leases, and (5) creating and promoting new livable urban neighborhoods.

City Actions would be done jointly or concurrently with development and include (1) implement the Heart of Peoria Plan with Smart Growth principles; (2) add parking and an enhanced streetscape on Washington Street; (3) reconstruct the historic character of existing streets around the Railroad Depot and Artist Alley with brick pavers; (4) optimize on-street parking with diagonal and parallel configurations; (5) create economic incentives such as TIF and Enterprise Zones to finance streetscape improvements and building renovations (6) lobby the state of Illinois to create a State Historic Tax Credit program for the District and facilitate the Federal Historic Tax Credit program; and (7) facilitate market research and area planning to promote the Warehouse District and the city as a livable community for business, culture, and living.

Some of these actions are already under way. The redevelopment of the Kellerher’s Block and the former Sealtest Ice Cream Factory are just two examples that are helping to revitalize the district. Another has been the adaptive reuse of 401 Water Street into prime office space (fig. 12.3). Dewberry Architects, Inc., which handled the design of exterior improvements and interior public spaces, occupies the seventh and eighth floors in upscale offices that provide dramatic views of the Illinois River. According to James Kemper, associate principal and design director at Dewberry, retrofitting an old warehouse building for modern offices is challenging. Wiring for modern data systems had to be routed under existing floors, and exposed ductwork for heating and air conditioning is suspended from structural beams. Sprinkler systems also had to be installed to meet stringent fire codes. Historical features, such as the water tower and an exterior materials chute, were retained and have become part of the aesthetic. The result combines modern materials and finishes with the historic warmth and character of traditional materials such as masonry and wood.

Community Profile: Changing Demographics

Peoria, over the past several decades, has successfully shifted from a manufacturing-based economy to one centered on professional and technical jobs. While Peoria is still its headquarters, Caterpillar Corporation’s local presence is dominated as much by its “white-collar” engineers, researchers, managers, and executives as by its “blue-collar” factory workers. As a result, Peoria has seen a dramatic increase in its “creative class” due to expansion of the economic sectors of health services, research, and development, higher education, finance, and law. The city has become a major medical center for most of central and downstate Illinois and a referral center for specialty disciplines beyond Illinois. To respond to this market growth, the three hospitals in the city are working together to invest over $500 million in capital expansion projects. Research and development activities valued at over $1 billion annually are being conducted by Caterpillar, Bradley University, the University of Illinois College of Medicine, and the National Center for Agricultural Utilization and Research, as well as up-and-coming companies like zuChem and IPICO Sports. In addition, Peoria is home to a number of regional banking institutions, as well as serving as central Illinois’s legal center as the county seat and having a federal courthouse.

Downtown Peoria employs nearly 20,000 people. This rise in the creative economy has changed the demographics of the city. Every day newly recruited engineers, doctors, lawyers, professors, and other professionals move to Peoria, often from large urban areas. While many of these transplanted individuals and families desire urban living, they find that opportunities to live close to where they work, in and around downtown, are limited.

In 2006, the city of Peoria retained the urban planning and design firm Ferrell Madden and Associates to assess and evaluate development patterns in the older sections of the city. That effort involved the study of the city’s demographic, employment, and housing patterns and determined that urban Peoria could support 3,600 new dwelling units between now and 2025.

Ferrell Madden found that between 1996 and 2005 the Peoria employment picture had shifted dramatically. The sectors that declined significantly were durable goods manufacturing, nondurable goods manufacturing, and retail trades.1 The areas with the most job growth in the same time period were education, health services, and professional business services. Given these patterns, the consultants projected that through 2010, the greatest growth would be in health and education, followed by professional and business services and durable goods manufacturing.

While Peoria has been growing outward in terms of land area, its population has remained relatively flat. The 2,100 homes added in the last decade have mostly occurred along the suburban north and northwestern edges of the city, not in the urban core. Throughout the metropolitan area an average of 1,200 housing units are built each year. Given the job trends, however, we believe there is a great opportunity for a denser, more urban housing product. As part of their study, the Ferrell Madden team looked at demographics from a study done by the Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) to project the lifestyle patterns of Peoria residents.

Of note in what the ESRI study termed “Tapestry Segments” is the significant number of people who are projected to be members of “Metropolitan,” “Midlife Junction,” or “In Style” segments. These three segments comprise approximately 30% of Peoria’s population (about 13,000 households). More important, demographers believe that individuals in these segments are more likely to be drawn to vibrant, urban environments. The Metropolitan segment, especially, is more likely to live in higher density areas with nearby big-city amenities.

Ferrell Madden also documented that Peoria is becoming a wealthier city. They projected that by 2010, the jobs added to the economy would result in a substantial gain in individuals earning more than $75,000 a year. Ferrell Madden also indicated that this gain is seen across all age categories, with significant gains in the population aged 55-64. This population segment represents a tremendous opportunity for upscale loft condominiums targeting “empty nest” professionals.

Peoria is an exciting market with an excellent potential for return on investments in its urban areas. Along with the demand for 3,600 new urban housing units over the next two decades, the same market will need over 220,000 square feet of retail space. The reinvestment in areas such as the Warehouse District will also drive demand for additional office space. Given the policies being implemented by the city — form-based codes and TIF — Peoria is a prime location for quality urban development.

Cost Base in the Warehouse District: Attractive Opportunities

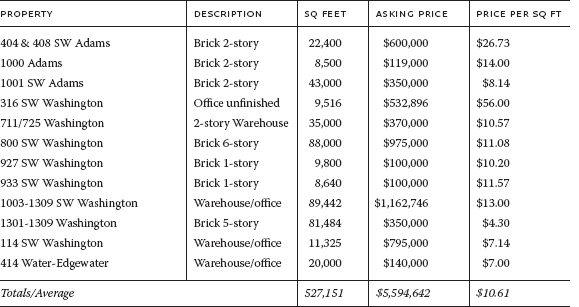

By any reasonable measure of real estate value, the cost base of properties in the district is attractive. Many of the buildings have sold for as little as $5 per square foot during the past five years. Over 400,000 square feet was listed for sale in 2006 for an average asking price of $11.87 per square foot, which was still a bargain. By 2008, costs had dropped further, reflecting the softer economy, with over 500,000 square feet listed for sale at an average asking price of $10.61 per square foot. Admittedly, many of the buildings have environmental, structural, and/or building envelope issues that need to be addressed.

Table 12.2 shows the average asking price for buildings in the Warehouse District in 2006. The average price was very low — a little over $10 per square foot. Thus, the land and building shell of a 1,000-square-foot condominium was only $10,000.

Economic Incentives: Tools to Motivate the Market

City governments today have a number of financial incentive tools that can be used to direct investment into underdeveloped urban areas. Public funding for urban redevelopment can come in the form of state- and federally-supported grants or loans, as well as partnerships with lending institutions, such as banks and mortgage lenders, the real estate divisions of insurance companies, and not-for-profit developers.

TAX INCREMENT FINANCING

The Warehouse District redevelopment area requires a TIF. However, without government incentives, the area cannot be redeveloped. For decades, this area has existed in its present condition and will probably continue as is without government support and leadership. The area qualifies for a TIF for a number of reasons, including the presence of vacant buildings, vacant land, deteriorated buildings, and poor infrastructure. Some of the buildings are obsolete for current uses, suffer from declining or stagnant assessed evaluation, have environmental problems, are located in the floodplain, or just suffer due to lack of insightful planning. The TIF would be a normal 23-year TIF, but the incremental incentive would be provided only for projects constructed within five years from the creation of the TIF. Development created after five years would pay normal taxes to all the taxing bodies.

TABLE 12.2 Asking Price for Properties in Warehouse District, Peoria, Illinois, 2006

Source: Courtesy of Ray Lees and Craig Hullinger.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION TAX CREDIT ACT

Federal historic tax credits are a major incentive to help cities renew older declining neighborhoods. The tax credit makes the preservation and renewal of dilapidated historic buildings much more likely and is an important factor in revitalizing older communities. The credit can be 20% of the investment in rebuilding historic buildings. A number of states have similar programs. The city of Peoria has proposed that the state of Illinois develop such a program, and the state legislature recently approved the proposal. The area now benefits from a 25% state historic tax credit.

Urban Living: Market and Demand

The city of Peoria in 2008 commissioned Tracy Cross & Associates to provide a market analysis regarding the potential for residential development in the city’s downtown, with particular interest in the feasibility of redevelopment within its Warehouse District. The city updated the study in 2009 at the request of developers, to determine if the market remained strong as the national housing recession deepened. Tracy Cross confirmed that the market remained strong and encouraged the city to continue to pursue its urban redevelopment goals.

The analysis demonstrates that the downtown of Peoria has the capacity to absorb 194 residential units annually, including higher density attached housing types. In fact, for the products/prices outlined below, the downtown/Warehouse District has the capacity to absorb 102 loft-style apartments converted from existing structures, 66 new construction rental apartments, 16 new garden condominiums, and 10 new construction townhomes/row homes.

Tracy Cross’s conclusions of aggregate potentials assume that a strategic approach to the introduction of new housing is taken with respect to both geography and the order in which the various housing forms are brought to market. This is to say, maximum absorption will most likely be achieved only with a concerted effort to introduce new housing in a way that extends the sphere of residential desirability and does so on an order that does not concurrently pit competitive housing forms against each other.

Much like other urban centers undergoing gentrification and redevelopment, the potential for Peoria’s downtown is very strong. The Warehouse District has already demonstrated its promise and feasibility as a place for new housing through several recent successful residential programs. In the meantime, the city of Peoria has supported additional redevelopment through the adoption of its innovative form-based zoning code and has approved generous incentives packages for developers and entrepreneurs. What is needed to continue Peoria’s downtown and Warehouse District revival is the application of a sensible and strategic plan of development that builds on existing strengths and maximizes the potential for future sites. (See plates 2 and 3 for the masterplan proposals for the Warehouse District.)

“If You Build It They Will Come”

A focus group comprised of young Caterpillar engineers and developers indicated a great interest among young people in living in a vibrant downtown neighborhood. “If you build it, they say they’ll come.”

Real estate developers who were contacted about building in the Warehouse District wanted to see market data demonstrating the interest level among people who were likely to live in new or renovated housing and commercial development around downtown Peoria. In conjunction with a number of city stakeholders, Peoria’s Department of Economic Development created a brief paper survey that gauged people’s interest in three distinct areas: (1) downtown Peoria, (2) the Warehouse District directly south of downtown, and (3) “Renaissance Park,” an area of older, single-family homes just outside downtown. The survey also gathered some demographic information about age, marital status, and other factors.

Initially, the survey was hand-distributed to a limited audience in order to refine the questions and get initial feedback. The interest level of those respondents was so positive that the city decided to release the survey more widely. Contracting with iceCentric, a Peoria-based technology company, the city made the survey available online from January 10 to February 10, 2006. Using the resources of the Chamber of Commerce and other local entities, employers were requested to ask their employees via email to complete the survey.

In one month, the survey generated 1,545 responses. According to iceCentric, the response rate exceeded the industry standard by 10%. Even better, the results themselves validated the city’s desire to have increased focus on these areas. Among respondents, 31.2% were interested in downtown, 30.2% were interested in Renaissance Park, and 29.6% were interested in the Warehouse District. Some respondents indicated an interest in one area but not others; in total, 42.8% of respondents expressed interest in at least one of the three areas in the survey.

The survey also yielded useful data about what types of people were most interested in these areas. Generally speaking, interested individuals were more likely to be single and have fewer dependent children living at home than those not interested. (In fact, 68% of all those expressing interest had no children living with them at the time of the survey.) There seemed to be an equal distribution among education levels and income, with interested individuals trending toward a slightly younger demographic than their counterparts. These demographics are important when talking to developers about what to build and to whom to market their developments.

An important feature of the survey was to determine what an ideal price range would be for those surveyed. The survey indicated the housing price range of people interested in these areas, as well as the types of property they are looking to buy.

Another important aspect of the survey was that people who were interested in living in one of the target areas were able to leave their email addresses on the site. The city now has 250 email addresses that will be provided to developers as they consider various development scenarios and potential clients. Under this scenario, the developer could get an option on a building, email all those interested, and invite them to visit the building. With very little expense and effort, the developer could get a quick response from prospective buyers or renters.

This housing survey proved to be a useful and inexpensive way to develop valuable market research. For less than $1,000, the city of Peoria now has some hard data to show developers that the areas specified in the survey will produce cost-effective and marketable investments for future developments.

Implementing the Vision: Strategies and Alternatives

While the successful redevelopment of urban areas is often a complex, frustrating, and time-consuming endeavor, the rewards for public and private stakeholders alike can be significant. The city of Peoria has assessed and quantified its opportunities and is laying the necessary groundwork to achieve its goal to revitalize the Warehouse District. However, success of future development will require the following initiatives.

DIRECT SALES OF LOFT SPACES FOR RESIDENTIAL PROPERTIES

Mature and more affluent clients will expect certain amenities and upgrades that lower income residents are willing to live without. In residential units, these may include natural stone countertops and high-end appliances in kitchens, more luxurious bathrooms with double sinks, walk-in showers and whirlpool baths, walk-in closets in bedrooms, and large, energy-efficient windows in living and dining rooms for light and views. Sustainable materials, such as low-VOC paints and carpets, bamboo flooring, and recycled materials will also be a marketing advantage for older, well-educated clients. Buildings with Leadership in Ecology and Environment Design (LEED) ratings also are more attractive to educated buyers who are willing to pay premium prices for sustainable environments.

RENTAL RESIDENTIAL UNITS FOR STUDENTS AND ARTISTS

For younger clients who are seeking minimal living requirements with the potential for work-related activities, warehouses that have been converted into lofts at a low cost per square foot will meet their expectations and pocketbooks. Minimal improvements would include new plumbing, electrical, and HVAC systems; new, energy-efficient windows; large, open live/work spaces with high ceilings; standard-grade cabinetry and appliances; ample storage; and green materials. Finishes can be kept to a minimum, however, which allows for the possibility of exposed pipes, HVAC ducts, and electrical conduit as aesthetic features of the building.

Figure 12.4. Waterfront Place in Peoria has antique and specialty shops that bring visitors to the district. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

RETIREMENT HOUSING IN SOME BUILDINGS

This is potentially a large and expanding market. Retirement housing for alumni who are affiliated with Bradley University is likely to be attractive to retirees who want to return to Peoria and live in quality housing overlooking the Illinois River. Bradley University could even hold continuing education classes in one of the buildings. Retirees from other businesses and institutions, such as the hospitals and Caterpillar, may also consider living close to the downtown, where they can walk or take public transportation to shopping, entertainment, and cultural activities.

A BED AND BREAKFAST OR BOUTIQUE HOTEL IN ONE OF THE CONVERTED LOFTS

The future residents of this neighborhood might not currently live in Peoria. A quality bed and breakfast or boutique hotel could attract visitors and entice them to spend time in the area.

EMPHASIZE THE AREA AS THE “RIVERFRONT ARTS DISTRICT”

The city and developers can work together to attract the “creative class” to locate in the district. Artists, photographers, architects, designers, and other creative professionals seek interesting areas of cities in which to live and work. In turn, they create and support various “microeconomies” that include retail, offices, and service businesses (Fig 12.4). Bradley University and Illinois Central College could also be recruited to hold art classes and develop studios in the district.

FIGURE 12.5. Redevelopment of the Kelleher’s Block in the Warehouse District of Peoria has inspired other building owners and demonstrates the potential of the district. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

WORK WITH THE CITY TO CREATE AN ENHANCED STREETSCAPE

Improve Washington Street from Main Street south through the Arts District with additional landscaping, signage, parking, and sculpture.

CONSTRUCT PEDESTRIAN-FRIENDLY STREETSCAPES IN THE ALLEYS

The alleys on both sides of Washington Street are exceptionally wide and invite significant pedestrian-friendly development. Whereas alleys are desirable for bringing food and services to and from buildings, they can have a dual purpose in the Warehouse District: (1) to bring goods and services to businesses and residences and to remove trash during nonpeak hours, and (2) to act as interior block walking streets for pedestrians lined with shops, galleries, and offices. In the SynergiCity masterplans (see chapter 2), the alleys were also an opportunity to introduce parking and pervious paving materials and filter strips to manage storm water ecologically. New streetlighting, ballards, plantings, and seating were also proposed to give the district historical character as well as enhance the livability of the alleys themselves (plate 4).

CONSTRUCT DIAGONAL PARKING TO OPTIMIZE PARKING POTENTIAL ON EXISTING AND NEW STREETS

The district streets are exceptionally wide and can easily accommodate parking. Diagonal parking has several benefits in this case, especially since it creates more compact parking areas adjacent to key businesses and residences.

BUILD NEW SINGLE-FAMILY AND TOWNHOUSE DEVELOPMENTS ON DEPOT STREET

There are people who would like to live in the area but will not want to own a converted loft space in an existing period building. Density can still be achieved by developing townhouses and midrise condominiums and apartments. The SynergiCity masterplan proposed designating the blocks along Persimmon Street as a Mixed-Use/Office/Residential district, which would enable mixed-use multifamily development for living and working.

CREATE INDOOR PARKING IN ONE OF THE SINGLE-STORY INDUSTRIAL BUILDINGS

Convert the first 30 feet of the street face of these buildings to retail. In planning, allow the conversion of these single-story parking garages into multistory parking decks if and when demand is sufficient. We also noted that many of the existing warehouses are built robustly enough to accommodate the weight of automobiles.

Will It Play in Peoria?

Since the days of vaudeville, Peoria’s Midwest sensibilities and values have provided stage acts, products, and services “tested” in our community with a measure of market viability and success before introduction to the national marketplace. If something successfully “played in Peoria,” chances were very good it would succeed anywhere in the United States.

Obviously, a targeted comprehensive urban redevelopment effort initiated during one of the most challenging economic environments experienced in a generation is no “stage act.” Only time will tell us if our community can weather the current downturn and successfully build on the substantial foundation already put in place by the city, planners, developers and others in this River City (fig. 12.5).

Note

1 Durable goods manufacturing saw a significant decline between 1996 and 2003 but has returned sharply between 2003 and 2005, though it remains below 1996 levels.

References

Duany, A., and E. Plater-Zyberk. 2003. Heart of Peoria. Peoria, IL: City of Peoria Economic Development Department.

Hullinger, C. H. 2006. Peoria, Illinois Economic Development Plan. Peoria, IL: City of Peoria Economic Development Department.

Hullinger, C. H., and L. McClellan. 2001, January. “Do You Have a Smart Growth Plan?” Illinois Municipal Review Magazine.

Hullinger, C. H., L. Schendl, and C. Setti. 2006, January 10–February 10. Survey Tells Developers “If You Build It They Will Come.” Med/tech market survey commissioned by the City of Peoria and administered jointly by the Economic Development Department and iceCentric, Inc. Available at the website of the City of Peoria, http://www.ci.peoria.il.us/index.php?module=resourcesmodule&action=view&id=779. Accessed January 6, 2012.

Tracy Cross & Associates. 2008, February 26. Residential Market Analysis: Downtown Peoria and the Warehouse District. Report presented to the City of Peoria.