Developing SynergiCity

THE REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVE

Many industrial cities in America’s heart-land and others elsewhere in the United States have endured long-term economic decline. Their manufacturing base has been undermined, and their central areas have lost many traditional economic functions, as well as population and employment, to peripheral locations. In an era of limited financial assistance from state or federal government, many cities are struggling to shore up their economic base and to strengthen central areas. Local civic and political leaders, economic developers, and downtown advocates have worked hard to attract private investment against long odds. In recent years, many can point to increases in private and public investment that indicate improvement. Although the recession that began in 2008 has derailed or delayed planned investments, redevelopment projects that leverage public infrastructure investments have become the favored vehicles for urban revitalization.

Even when markets improve, private investors are usually too risk-averse to pursue redevelopment projects without significant public assistance. That is why almost all urban redevelopment efforts involve public-private partnerships (Frieden and Sagalyn 1989; Kotin and Peiser 1997; Sawicki 1989). Local governments, community-based organizations, foundations, neighborhood groups, and other community advocates typically represent the public sector. Real estate developers and investors, commercial bankers, and tenants or their brokers represent the private sector. These participants seek ways to increase private returns in order to attract investment capital to redevelopment projects at reasonable public cost. In some cases, however, scarce public resources have not been utilized effectively, which slows the pace and reduces the impact of redevelopment (Meyer and Lyons 2000).

Since the mid–1980s, income tax rates, capital gains treatment, depreciation schedules, and loss provisions have significantly reduced the tax-shelter benefits of real estate ownership. The federal tax credit programs that exist are for low-income housing, historic preservation, or low-income areas (New Markets). Even when these programs are fully utilized, socially beneficial urban redevelopment projects must be both economically viable and financially feasible if private equity and debt are to be secured on reasonable terms (Adair et al. 1999; Gyourko and Rybczynski 2000).

Local leaders and concerned citizens often have a physical vision of revitalized central areas that is far ahead of market realities, as it should be. The difficult task involves attracting sufficient local and/or external demand to expand the local market in order to make the vision feasible. We must merge civic vision with economic and financial realities to achieve urban redevelopment.

This chapter focuses on real estate redevelopment in postindustrial cities. Rather than survey success stories, the emphasis is on the economic and financial dimensions of redevelopment at both the project and strategic levels. These dimensions must be addressed to achieve greater investment and improve property values. Ideas and guidelines are presented about ways to increase private investment through public-private partnerships. When local demand increases, private investment can be stimulated by increasing revenues, reducing costs, or — most important — lowering the perceived risk associated with redevelopment. Numerical examples are provided to help the reader understand the economic and financial realities of urban redevelopment more fully. (For an excellent review of this general topic, see Sagalyn 2007.)

Project-Level Approaches

Private developers use “baclc-of-the-envelope” techniques of financial analysis to compare value to cost in order to gauge the attractiveness of competing development opportunities at the outset of the development process. Project value is found by dividing estimated net operating income (NOI) by the appropriate market-determined capitalization (cap) rate. Net operating income is simply gross revenue (current market rent multiplied by the number of units or square footage of the project) reduced by vacancy allowance and operating expenses. The cap rate comes from transactions involving comparable properties. The cap rate can be considered the overall return investors expect per dollar invested. In other words, a 9% cap rate reflects the expectation that investors will earn 9 cents for every dollar used to purchase a property. Project cost is estimated by adding to the cost of the site construction costs per unit or square foot. Developers consider many projects, but few are sufficiently attractive to pursue.

The urban redevelopment context is quite different. The city administration, local economic development organization, or downtown advocacy group identifies potential redevelopment sites in central areas. The lead entity usually calls for public input on redevelopment options. Through charrettes or other means, it fashions a plan or vision for the physical redevelopment of small areas or specific sites. This plan or vision should be consistent with legal and institutional requirements as well as the site’s physical constraints. At this point, the decision to redevelop depends on whether the numbers will work. In other words, feasibility depends on economic and financial considerations.

One difference in approach is that private developers almost always begin with a use (property type) and then try to find the most appropriate site. Local developers limit their search to available sites in the local market. Regional and national developers survey larger geographic areas and then narrow down to neighborhoods and finally specific sites. On the other hand, redevelopment projects promoted by the public sector almost always begin with specific sites within redevelopment areas. The question becomes: what is the most fitting and appropriate use for the site?1 Private developers begin with a use and then determine whether an appropriate site exists for the project. Publicly inspired projects do not have this flexibility and must do sufficient feasibility research to review many potential uses as well as a combination of uses (mixed use).

Another rather obvious difference is that private developers usually build new products on “greenfield” sites. Urban redevelopment projects begin with infill sites that have been used previously or buildings that should be preserved through adaptive reuse (fig. 13.1). Both differences reflect the fact that private developers and their equity investors are footloose, whereas public redevelopers are committed to specific places.

Figure 13.1. The lobby of Harvester Lofts in Minneapolis combines historic elements and contemporary furnishings and finishes to attract young buyers. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

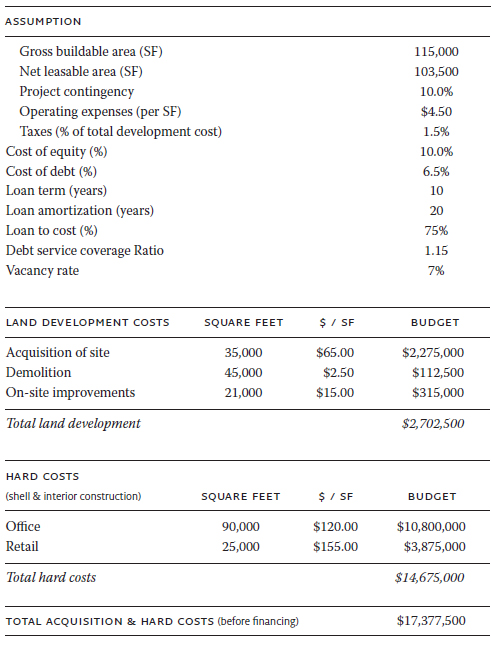

Given an infill site or existing building, the first step is to estimate the cost of the redevelopment project. Although an array of public incentives and subsidies is usually available, cost estimates should be made without the inclusion of subsidies. These cost estimates are organized in the capital budget for the project. The budget should include best estimates of land and site development costs, construction costs including the structure and all systems (hard costs), and associated cost of services (soft costs).2 appendix A shows a hypothetical capital budget for an urban redevelopment project.

Once the capital budget is estimated, financial and market realities can be introduced. James Graaskamp developed a straightforward static method to conduct this analysis (Appraisal Institute 2008; Ciochetti and Malizia 2000; Graaskamp 1981). The cost-driven approach begins with the project capital budget and estimates the rent levels required to support this cost. The market-driven approach begins with existing market conditions and finds the project cost afforded by the market.

With the cost-driven approach, project cost as presented in the capital budget needs financing. Most real estate projects are leveraged, which means that the project is financed with permanent debt as well as equity. By introducing debt and equity, the financial dimension essentially links the cost estimates to existing market conditions.

Lenders apply two basic criteria to evaluate any loan request — the loan-to-cost (or loan-to-value) ratio and the debt service coverage ratio. In this case, the loan-to-cost ratio would be used to determine how much private debt could be provided. This ratio would usually vary in the 60–80% range. Private equity would be sourced to provide the rest of the financing.

The annual cost of private debt is not difficult to ascertain. Commercial lenders can quote the expected terms of the permanent loan — interest rate, amortization period, term of loan, and other provisions. These parameters can be used to find the monthly amount of debt service needed to repay the loan. The mortgage constant is amount of monthly debt service paid per dollar of principal. This constant is multiplied by 12 to find the annualized monthly mortgage constant.

The cost of equity is less accessible since real estate developers often rely on informal sources of equity (friends, family, business associates, etc.). In this static model, what is needed is an estimate of the cash-on-cash return on equity. In other words, how much cash would the project have to generate for equity investors to contribute one dollar of equity?

The annual return on equity and cost of debt add to NOI. The logic here is that the project’s NOI will be split between the lenders and owners of the project. Project revenue is estimated by adding operating expenses, including real estate taxes and the vacancy allowance to NOI. The project size, either in square feet (SF) or units, is divided into project revenue to find the rent level required to develop the project. For most urban redevelopment projects, market rents will be below the rent required to support project cost. The question is, how large is the difference between market rents and the rent level needed to make the project feasible? Costdriven analysis is shown in appendix B. With the costs reflected in the capital budget (appendix A) the cost-driven analysis indicates that the hypothetical redevelopment project is not feasible. The spreadsheet showing the market-driven analysis is included in appendix B.

Cost-driven/market-driven analysis is a powerful tool to evaluate redevelopment alternatives. The analysis is especially valuable because the information needed is not extensive or difficult to gather. Given the existing preference for mixeduse redevelopment projects, the analysis involves finding the combination of uses that offers the least infeasible projects. These projects are financially infeasible because project cost is greater than project value. Still, they represent the ones that require lowest amount of public subsidy, given market realities. The analysis can be refined by figuring out how much of each use should be included in the project and by evaluating this mix of uses on several potential redevelopment sites. The best options that come out of this analysis can be described in a Request for Qualifications (RfQ) or Request for Proposals (RfP) (described below) in order to attract the most qualified private developers.

PUBLIC SUBSIDIES

The lead public entity must decide whether subsidizing the project at the required level is financially and politically feasible. If the entity wants to pursue the project, the dynamic (discounted cash flow; DCF) analysis or static analysis (cost-driven/market-driven analysis) can be used to examine the impact of different forms of public participation in the project (sensitivity analysis). The underlying question to be answered is: does the redevelopment project provide sufficient public benefits to justify the public subsidy (Malizia 1999; Sagalyn 1997)?

Infeasible projects show cost (as reflected in the capital budget) greater than value (NOI/cap rate). For the redevelopment project, this difference is an initial estimate of the amount of subsidy required.

However, DCF analysis should be used to get more accurate results. The DCF methodology for estimating public subsidies is described and illustrated in appendix C.

It should be noted that entities promoting redevelopment often do not conduct this type of analysis. Instead, they employ what might be called the “buffet” approach. They usually have many types of subsidies available, everything from facade improvement programs to concessionary financing. They invite the private developer to select all the items from the buffet that appeal to his or her taste. With this approach, the developer can figure out whether to proceed with the project, but the public will learn nothing about the economics of the deal or whether too much subsidy has been provided. The public needs to know the economic and financial details of the project, given the objective of fashioning cost-effective public-private partnerships.

In general, urban redevelopment projects can be subsidized by increasing revenue, reducing cost, or lowering risk (Hodge 2004). The public entity can increase project revenues by boosting rent or decreasing vacancy. It is not prudent for the public to overpay for space. However, every project expects some level of vacancy loss, and the public can boost revenues by occupying space at market rents for the long term that otherwise might have remained empty.

By far, the most common subsidies involve lowering project cost. The capital budget in appendix A provides many subsidy opportunities. Lowering or eliminating site acquisition cost is one of the most popular.3 Public entities can also provide or pay for site development, including demolition costs.4 Although less common, the public can also contribute to the long list of professional fees and studies needed to plan and review the project. For example, public entities could conduct surveying, appraisals, or land planning. Or the public entity could encourage private consultants to provide some of these services pro bono. The public may also waive fees or pay for impact studies.

With respect to operating expenses, many jurisdictions have the authority to reduce, rebate, or eliminate ad valorem property taxes (fig. 13.2). Although the impact can be significant, the reduction of tax revenues and potential increases in public borrowing should be explicitly addressed as opportunity costs. The best approach is to conduct a fiscal impact analysis.5 For projects with positive fiscal impacts, the tax abatements could be limited to equal the excess revenues. For fiscally neutral or negative projects, the public entity would have to gauge how much burden to place on the public sector to offer tax abatements. For these projects, the abatement could be limited to the early years of the project and reduced over time as NOI increases.6

Finally, many public entities participate in redevelopment through concessionary financing. Typically, some portion of the permanent financing is provided by a community development financial institution (CDFI). In comparison to private financing available in the market, the CDFI’s financing is offered at lower cost (interest rate), longer term, longer amortization period (or interest only), and in some instances flexible repayment schedules. The financing is subordinated to private debt. Although the public entity may take an equity position in the project, this is not typical. Most public objectives can be achieved with flexible debt financing without assuming the complications and risk of project ownership (Malizia 1997; Meeker 1996).

The importance of risk reduction at the project level is not widely recognized, in part because it is indirect. Yet its impact can be profound and cost effective. All participants in the redevelopment project price their services in relation to risk; the higher the risk, the higher the necessary return. Equity investors, permanent and construction lenders, and general contractors are the most important participants in this regard.

FIGURE 13.2. Urban projects are often made possible through incentives provided to developers by the city, for example the 730 Lofts, designed by Urban Works Architecture, on 4th Street in the Warehouse District of Minneapolis. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

For the contractor, site development and building restoration are the most difficult costs to assess. The public entity could assist in site assessments, including soil borings, and in building inspections and testing. The public entity should ascertain the estimated cost reductions forthcoming from the contractor before pursuing these activities. In general, the contractor should work for a lower margin and/or require less contingency when the public entity reduces development risk.

The construction lender can reduce project cost when the public entity participates to lower risk, increase revenues, or reduce costs. The construction lender should respond by requiring a smaller project contingency and/or lower adjustable interest rate. Construction interest is also lessened when the project takes less time to complete. Although few options exist to reduce construction time, the public sector can offer timely building inspections and the certificate of occupancy (CO) issuance on completion.

In addition to lowering project cost, concessionary permanent financing lowers financial risk and should therefore impact the permanent private loan. When the public provides a subordinated second mortgage loan, the private lender’s exposure is greatly reduced. The impact is similar to increasing equity, which reduces the loan-to-cost ratio. Concessionary financing often boosts the debt service coverage ratio, which also reduces risk. Moreover, the public entity can directly reduce private lending risk by guaranteeing the private loan.

In response, private lending terms should be improved, lowering project cost further. When concessionary financing is in play, the private loan should be negotiated at better terms — lower interest, longer term, and/or longer amortization period. The amount of the loan may also be increased, lowering project cost further by replacing some of the equity required for the project. This outcome reflects the fact that debt is cheaper to secure than equity because creditors assume less risk and earn less than equity investors.

Equity investors form expectations by comparing risk and return for different opportunities.7 They view urban redevelopment projects as carrying more risk than projects in locations where the market is more established or robust. Therefore, their return requirements are higher.

Public entities can work with developers to help educate their equity sources about the many ways that project risk is expected to be lowered through public participation. All of the methods that reduce costs or raise revenues could reduce equity return requirements to some extent. The problem is that most equity investors have experience only with new development in peripheral locations. These projects appear to be lower risk than urban redevelopment projects. Even with information about how the public-private partnership is lowering risk for project owners, many equity investors may still require higher returns. The fact that typical equity investors lack experience with redevelopment would elevate return requirements even if the redevelopment project were objectively no more risky than a suburban alternative.8 Return requirements are ultimately subjective. Still, any reduction achieved in equity return requirements would increase project value at no additional public cost.9

In addition, public entities could try to recruit potential investors directly and educate them about urban redevelopment. As a result, these investors may seek more modest returns on projects they come to understand well. With effective communication about the details of redevelopment projects, the cost of equity could be reduced with minimal additional public outlay.10

When the redevelopment project has achieved stabilized occupancy, it is an operating enterprise that should have positive cash flow with public subsidies included. Effective property management is essential to maintaining and improving this enterprise over time. Public entities promoting urban redevelopment should network to find good property management firms, since many real estate developers do not have property management capacity within their firms (fig. 13.3). The public sector can use the RfQ/RfP process to identify and select the most attractive property managers.

Generally, public entities initiate the redevelopment process by issuing RfQs. The responses enable the public to consider how different developers would approach the prospective redevelopment in relation to their development experience. Once the qualified firms are selected, the public entities issue RfPs. Only the qualified firms can respond to the RfP. Once the firm is selected, the public entity formalizes the partnership agreement that lays out the expectations and responsibilities of all participants.11

This discussion of redevelopment at the project level assumes that the objective is to increase private investment in urban areas for economic revitalization and physical renewal. The important related objective is to redevelop in a sustainable manner. Sustainable development has many meanings. In this context, sustainable redevelopment or green redevelopment pertains both to construction and ongoing building operations.12 The evidence suggests that construction costs are increased marginally as a result and that operating costs can be lowered substantially. Although the research is limited, sustainable/green projects also achieve higher than average market value (Dermisi 2009). Evidence also exists that worker productivity and turnover are lower in healthier work environments (Miller et al. 2009). Sustainable practices in construction are promoted by Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) whereas ENERGY STAR is the best known vehicle promoting sustainable/green building operations.

Figure 13.3. Interior of Franco’s Restaurant, a prime tenant in the Soulard Square Lofts in St. Louis. Successful businesses bring people to urban districts and encourage further development. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

Strategic Approaches

Public strategies that promote urban redevelopment can be designed to influence the expectations and behaviors of private actors. The sources of debt and equity capital are addressed here to cover the financial dimension. The next section considers ways to increase local demand, which covers the economic dimension. (This section draws from Malizia and Accordino 2001 and Malizia 2003; see also Leinberger 2005.)

In general, lenders and other sources of debt capital underwrite urban redevelopment projects more conservatively than more robust projects and commit less debt capital to them.13 Another disincentive is that commercial lenders do not have access to secondary markets, given the uniqueness of urban redevelopment projects. Therefore, the capital devoted to these projects remains committed and is not replenished by another financial source that purchases the loan. For a related discussion of development lending, see Gordon (1997) and Jackson (2001).

Commercial lending behavior deserves further attention, especially during periods when credit is difficult to access. Unlike investors who can seek higher returns by accepting greater risk, prudent lenders have to take a different approach to the deployment of debt capital. Lenders determine a comfortable, presumably modest, range of risk in identifying “creditworthy” projects. They charge similar interest rates to these projects when they allocate funds to them. If the project exceeds its expected rate of return, the owners benefit; lenders earn the same amount of interest. Therefore, lenders worry about downside risk much more than the upside earnings potential. They ration credit to the projects they prefer.

On the other hand, if lenders pursued projects with the highest expected returns and charged higher interest rates afforded by these high return expectations, they would end up holding a portfolio of loans that would be high risk. The conventional wisdom is that greater potential earnings from high-risk loans would not compensate for the additional risk assumed (Wood and Wood 1985).

With respect to equity capital, investors consider both amount and timing of equity infusions, as well as holding period, in determining return requirements. They expect to earn more than tax-credit investors who infuse equity late in the development process, after construction and substantial leasing have been completed. When equity investors are asked to infuse equity during early stages of the project or provide the balance sheet that is used to guarantee the construction loan, their equity return requirements increase.14

Figure 13.4. In many places in the United States, low financing rates for housing help both developers and buyers, for example Cotton Mills Condos in New Orleans, the first complex in the Warehouse District to be approved for FHA financing. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

Given these expectations and behaviors, public sector entities should formulate strategies to lower risk in order to promote urban redevelopment. Four strategies to reduce financial risk are presented below: (1) develop and steadfastly implement small-area revitalization plans, (2) concentrate infrastructure improvements, (3) use triage when necessary, and (4) promote competition.

All of these strategies are designed to reduce the uncertainty and risk involved in urban redevelopment. The most significant source of uncertainty is the wide range of informed and uninformed opinions that exist concerning the redevelopment potential of central areas. Appraisers have difficulty valuing inner-city projects accurately, due to thin markets (few transactions). The absence of good comparables increases the influence of opinions and other subjective factors. Existing property owners who derive income from current land uses have a vested interest in having an optimistic outlook on the long term. Developers may envision viable uses for central-area sites, but only if the properties can be secured in the near term at reasonable prices (fig. 13.4).15 Investors usually have a wider range of assessments about risk and uncertainty than developers or property owners. Some investors are attracted to urban redevelopment projects; others have little interest in them. Because transactions are infrequent and projects are complex, markedly different investment outlooks may be justified for central areas. However, such differences of opinion form a major barrier to attracting the resources needed for urban redevelopment because they ultimately lower the value of potential projects.16

SMALL-AREA PLANS

Physical plans have always served as a framework to guide development over the long term. As a risk reduction technique, small-area planning is critical because it significantly reduces the number of alternative futures that could pertain to specific central areas or neighborhoods. Good graphics and visual representations of what the neighborhood could become are important ingredients in changing attitudes about places. However, risks will not be decreased with visioning or general land-use proposals alone. The best plans identify which public improvements will be made, where they will be located, and when they will become operational. In other words, planning and zoning should be linked to capital improvements programming to carry small-area plans forward.

Considerable political will is needed to implement such specific small-area plans, but jurisdictions that reduce risk and uncertainty in this way should be rewarded with increased private investment. At the same time, local governments should pursue strategic land banking to help ensure that asking prices for land in locations earmarked for redevelopment that may well increase do not become a disincentive to further redevelopment.17

CONCENTRATED INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENTS

Local politics as usual calls for resource allocations that spread funds among neighborhoods. Smallscale public investments that are dispersed widely rarely change perceptions that can reduce risk. It is much more effective, but politically difficult, to concentrate resources in strategic locations. Such investment can encourage larger projects that achieve adequate scale. Projects that cluster development around strong neighborhood anchors are likely to be more successful.

Urban redevelopment resembles an invasion that must first establish a beachhead in one location before it can spread to adjacent land. Without adequate infrastructure, project scale, and concentrated development, a beachhead cannot be firmly established. With success at one location, redevelopment should gradually spread to proximate sites. As projects accumulate and deals become self-sustaining, market information improves. As a result, confidence intervals around forecasts should narrow, and the associated risk should go down. Over time, property values in targeted central areas or neighborhoods should increase.

TRIAGE

Certain areas may be too expensive to help, at least in the near term, given limited resources and the need to concentrate public investments spatially to achieve adequate scale. In these areas, most residents and businesses will want to stay, but some may want to be relocated. The public entity should help them find more viable locations. As harsh as this option may seem, private investors will come to understand that the public sector intends to ignore these areas for some period of time. As a result, asset values may decline. Over time, increased certainty about the future of these areas will narrow the range of investment alternatives considerably. More certainty should provide a countervailing tendency that may gradually increase investment. Eventually, asset values in these areas may begin to increase.

The triage strategy is worth considering even if eventual increases in asset values are not forthcoming. As will be discussed later, successful urban redevelopment draws on many different ideas that require different spatial locations. Relatively cheap sites and structures are often needed in central areas because many desirable businesses and residents can only afford modest rents.

More broadly, not all cities are experiencing sustained population and employment growth. In declining places, the market is implementing the triage strategy as firms close and people move out. It is extremely difficult for the public sector to invest sufficiently to overcome these market forces. It is usually prudent to accept them. On the other hand, the political challenges of implementing the triage strategy decline significantly in shrinking cities.

COMPETITION

The public sector can promote competition among developers and investors if central areas, in fact, provide viable investment opportunities. Strategic public investments and specific small-area plans should increase the attractiveness of specific sites and the value of property at locations where the market becomes strong. Currently, most redevelopment opportunities exist in “buyers’ markets,” where private developers are scarce and are able to exact major concessions from the public in return for buying sites and investing in redevelopment projects.

Local jurisdictions should try to make certain areas sufficiently attractive to create “sellers’ markets,” where private developers are lining up to buy or option sites in order to participate in urban redevelopment. The competition among private developers should drive up asset values, make redevelopment projects in these locations more feasible, attract even more private investment, and create opportunities to recapture appreciating property values for the benefit of the community (plate 8). As more private capital flows to urban redevelopment projects, community residents should realize more local services, jobs, business opportunities, and wealth creation.

The shift from buyers’ to sellers’ markets can only occur when local governments have targeted attention and resources to a few strategic sites in key locations, rather than dispersing scarce resources throughout the entire city. In addition to basic infrastructure, the public entity should identify public investments that create anchors on strategic sites. Such investments can conserve public resources in the long term by lowering the public subsidies required to promote public-private redevelopment projects. Potential anchor investments include city or county government facilities, educational institutions, sports facilities, civic centers, performing arts centers, museums, and public or civic open space.

Market Expansion

Urban redevelopment is limited by the extent of the market. In this context, the economic dimension of real estate development is most usefully addressed by focusing on market expansion. Real estate developers rely on real estate market research to gauge the depth and breadth of the market. They conduct in-house research and also rely on market analysts and appraisers to conduct formal market and marketability studies (Ciochetti and Malizia 2000; Fanning 2005). This work generally involves forecasting demand and competing supply to determine whether sufficient excess demand exists to warrant the project. Market risk is mitigated when development projects can provide the supply response to identified market opportunities.18

The challenge is to increase space demand in order to solicit supply response in the form of urban redevelopment. Economic developers work hard to increase the competitive advantage of their location to investment. Place-based strategies attract, expand, retain, or create businesses that provide jobs.

Recruiting businesses is by far the most common local economic development strategy and the core practice of economic developers (plate 15). Investment from external sources provides local jobs and increases the tax base. Economic developers also work with existing businesses to assist with expansions or restructurings that retain employment. Since most employment is provided by these businesses, attention to their needs is important. Strategies to promote local entrepreneurship (creation strategies) have become increasingly popular, especially during economic downturns. They range from providing basic support for small businesses to creating the milieu for new businesses to mobilizing the resources needed to identify and foster emerging growth companies. (A detailed discussion of economic development planning, strategies, and practice is presented in Blakely and Green Leigh 2010 and Malizia and Feser 1999. For more specific applications, see chapter 12.)

People-focused strategies have recently become popular, partly inspired by the work of Richard Florida (Florida 2004, 2005). Many jurisdictions have developed strategies designed to attract people under the assumption that jobs will follow. However, it is not clear that this strategy is more effective than traditional approaches to job creation. (See, for example, Donegan et al. 2008.) These strategies include downtown redevelopment, tourism development, adaptive reuse of industrial properties, historic preservation in residential areas, increases in parks, trails, and open space, improvements in education at all levels, public health initiatives related to physical activity and nutritional local food, and so on (plate 13). But these strategies can only succeed if in-migrants are in fact able to find jobs. These people-focused approaches are clearly easier to implement in large or growing metropolitan areas. However, they can succeed in declining areas when linked to effective place-focused strategies.

Thus, it makes sense to combine these approaches since the local market will expand either way. Successful local economic development expands the local market as aggregate disposable income increases due to job growth. Employment opportunities in the regional economy are just as important, because they can provide jobs for local residents who become out-commuters. Jobs are also created when the existing population and tourists/visitors are better served. Moreover, the ability of the local workforce to bargain for higher wages and salaries is another effective way to increase aggregate demand.

In summary, place-based strategies attempt to expand or improve the local economic base in order to increase the demand for labor (job creation). People-based strategies attempt to increase or improve labor supply, either by providing education or training or with more attractive living opportunities. A third approach is to consider ways to expand nonbasic sectors, which are the ones that serve only the local market.

It may seem unnecessary to be concerned with nonbasic sectors when success from either place-focused or people-focused strategies will automatically generate demand in these sectors. However, in the context of the global economy, the linkage between increased local demand and growth in local businesses is far from automatic. First, “leakage” — the difference between local disposable income and local purchases — may increase. In addition to mail-order purchases, internet purchasing is increasing. More mobility leads to more purchases during trips outside the local area. Second, “inflow” — purchases from outside the primary market area — may decline. Neither residents nor nonresidents (tourists) will purchase from local businesses that do not meet their quality or price standards; as noted, convenient alternatives exist. Thus, it is vitally important to attend to strategies designed to assist local businesses. Chambers of commerce should want to assume leadership in this area.

One strategy with considerable potential would focus on local entrepreneurs. To the extent that entrepreneurs are exporting goods or services (part of basic sectors), they are already in the scope of local economic developers pursing “creation” strategies. Ones that are in nonbasic sectors are more likely to be overlooked. Two groups exist. One group of local entrepreneurs is running unique local businesses. The other group own or manage franchises, usually more than one.

Some owners in the first group may be in a position to seek locations in urban redevelopment projects. Forging the connection between these entrepreneurs and local developers should contribute to their mutual success.

One barrier stems from the fact that these young local businesses often have weak credit ratings.

Some form of credit enhancement would increase their attractiveness to redevelopment project owners. It may be possible to find locally based corporations, hospitals, universities, or public entities willing to guarantee the rent payments of these businesses. The established entity would cosign the lease.

Other local businesses may have outgrown the home office but are not seeking upscale office space. These young businesses need cheap space. Areas not targeted for redevelopment that are physically safe could offer “funky” space for these prospective tenants. As noted, areas not targeted for redevelopment are very important, because they represent affordable locations for young local businesses or even somewhat marginal ones. Business incubators and business accelerators could be located in these areas (plate 7).

The franchisees may not need additional business support, but local chambers of commerce or business associations should solicit their ideas. Simply convening them to facilitate the development of peer groups and networks can be beneficial.

In most areas, franchise businesses are not in central locations. Since most are creditworthy, they would be attractive tenants in urban redevelopment projects. As housing expands in central areas, it may become feasible to attract these businesses to redevelopment projects in these areas.

Taken together, strategies to foster both types of businesses in nonbasic sectors hold considerable promise. Certainly, latitude exists for creative thinking. More local jobs, more out-commuting, more successful local businesses, and higher wages and salaries will increase disposable income and aggregate local demand. These outcomes would expand the local market and foster urban redevelopment as a result.

Conclusion

Effective public interventions at the project and strategic levels can promote urban redevelopment. At the project level, techniques of financial analysis can be used to gauge project feasibility, estimate appropriate subsidies, and conduct sensitivity analysis. Financial feasibility can be increased by increasing project revenue, reducing project cost, and, most important, mitigating financial risk. At the strategic level, small-area planning, public infrastructure investments, and consistently applied priorities can make selected locations more attractive to private investment. Economic development strategies can enhance the local market, which will increase demand for redevelopment. They may focus on place, people, or entrepreneurs operating in nonbasic sectors.

Appendix A

CAPITAL BUDGET EXAMPLE

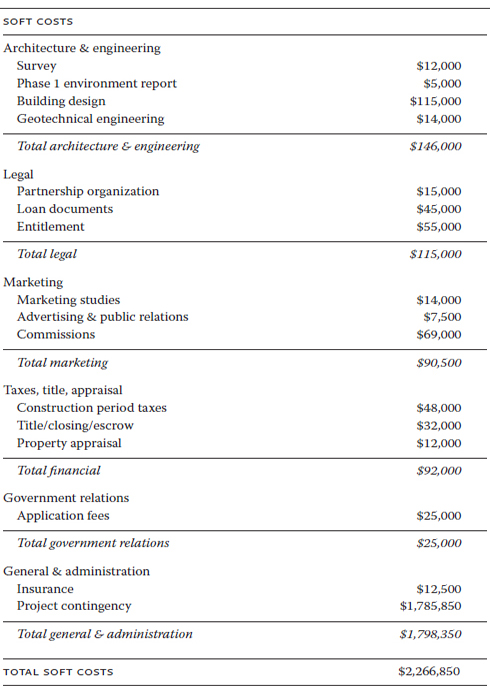

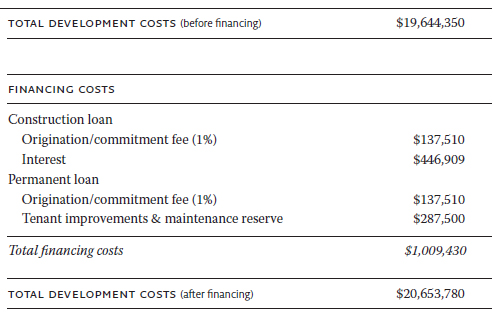

The hypothetical redevelopment project is located on an infill site where demolition is required. The proposal is to develop retail and office space at an estimated total cost of about $20 million. The summary budget provides estimates of land acquisition and development costs, hard costs, soft costs, and costs associated with construction financing (table 13A.1). General contractors estimate hard costs in much greater detail. The unit price categories typically used are shown in table 13A.2.

TABLE 13 A.2 Site Work and Hard Construction Cost Elements (based on Construction Specification Institute Format)

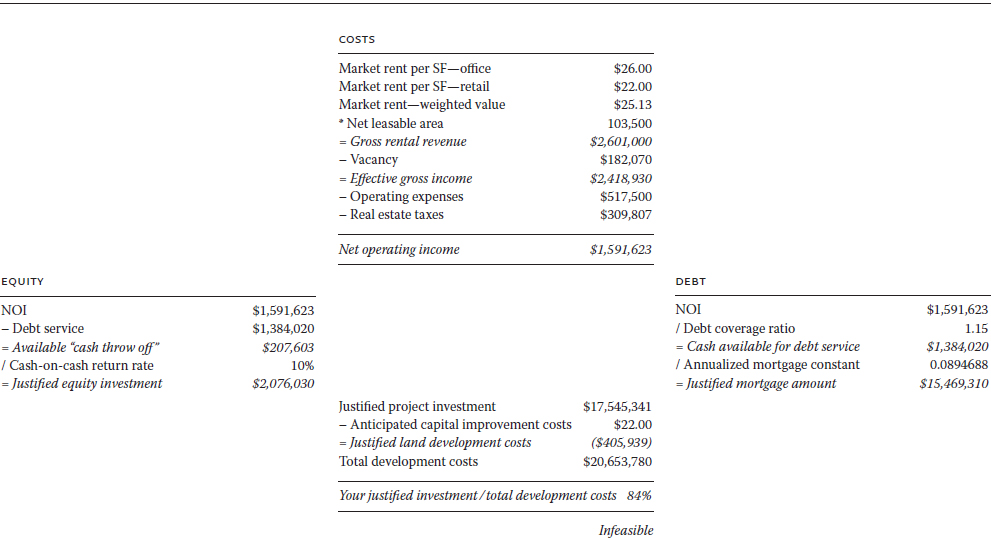

COST-DRIVEN/MARKET-DRIVEN ANALYSIS

The static cost-driven analysis begins with the project costs that are given in the capital budget and ends with an estimate of the required rent needed to make the project feasible. Since retail and office are the projected uses, current market rent is the weighted average of current rent for each use. The proposed redevelopment project requires rent that is 9% over market, which means that the project is infeasible (see table 13A.3). The market-driven approach is shown in table 13A.4. Given market rents, the project can attract only 85% of the capital needed to redevelop the site.

As noted, one can conduct sensitivity analysis with these static models to examine the impact of various subsidies. However, it is more accurate to use the dynamic DCF model to analyze the project’s performance over time, as shown in appendix C. This model should be used to conduct sensitivity analysis.

TABLE 13A.3 Cost-Driven Analysis using Loan-to-Cost Ratio

TABLE 13A.4 Market-Driven Analysis using Debt Coverage Ratio

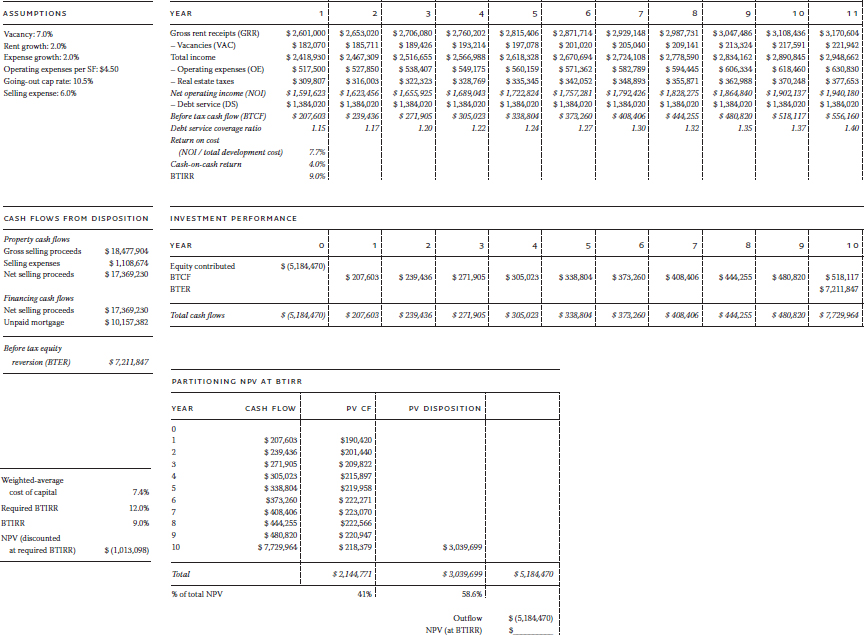

TABLE 13A.5 Discounted Cash Flow

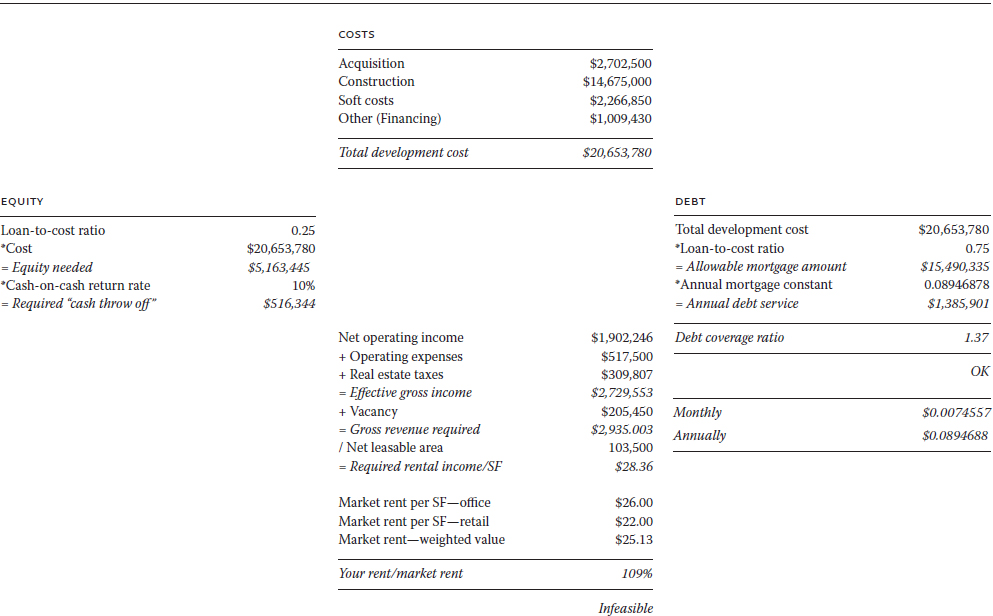

DISCOUNTED CASH FLOW ANALYSIS

This type of analysis is used to examine the financial dimension of the redevelopment project and, most important, to estimate the subsidy needed to make it feasible. The simplified analysis assumes that equity is invested in year 0, the project achieves stabilized occupancy in year 1, cash flows for the 10-year holding period are driven by the assumed rents and expenses, the project is sold at the beginning of year 11, and expected NOI in year 11 is divided by the going-out cap rate of 10.5% to estimate sales value.

The accuracy of this analysis can be improved by using months as the time period instead of years. In this way, cash solvency over the development period and the important development risk areas, such as entitlement risk and lease-up risk, can be examined. In addition, returns can be estimated more accurately with monthly figures. Although the developer should conduct monthly analysis, public participants will find the inputs for annual analysis easier to estimate than monthly figures. They should prefer annual analysis because it is sufficiently accurate and would tend to estimate lower required subsidies, given the time value of money.

From the analysis presented in table 13A.5, return on cost is 7.7%, cash-on-cash return at stabilized occupancy (year 1) is 4.0%, and before-tax internal rate of return (BTIRR) for the holding period is 9.0%. An analysis is also shown that calculates the share of returns from cash flow compared to the share from the residual, which represents the net proceeds from the sale of the project after the mortgage balance is paid. Almost 59% of total returns come from the residual.

Discounted cash flow analysis can be conducted using the 12.0% BTIRR that equity investors expect as their hurdle rate (discount rate). At this hurdle rate, net present value (NPV) is in the red by more than $1.0 million. Thus, equity investors would not invest in this project because it fails to meet their return requirements. The project would become feasible if the public sector generated $1.013 million in subsidies. With these subsidies, NPV would be approximately zero at the 12% discount rate.

As noted, public subsidies could either increase project revenues or, more likely, reduce project costs. Project feasibility is also affected by risk perceptions. Three typical ways to lower project costs and their impact on returns are presented. First, if the public sector donates the redevelopment site, it will generate $1.4 million more subsidy than needed and 16.3% BTIRR, well above the required 12.0%. Second, reducing site cost to $38 per SF should enable the developer to do the deal. Third, if the public sector abates taxes from 1.5% to 1.0% of total development cost, which is used as the estimate of assessed value, the project becomes feasible. Similarly, concessionary financing at 5.0% interest provides slightly more subsidy than needed.

Changes in risk perceptions can significantly impact returns. Since risk perceptions can change without incurring the costs of direct subsidies, public participants should try to influence private perceptions in positive ways. If the going-out cap rate were reduced by 160 basis points to 8.9% to reflect growing investor optimism about the redevelopment area, the project becomes feasible without direct subsidies. At this cap rate, the residual value (sales price) of the project increases significantly from $7.7 million to $10.9 million.

Although the numbers in these spreadsheets are all based on assumptions and represent forecasts, DCF analysis is a powerful tool to use in negotiating public-private partnerships. First, the public entity can calculate the impact of various tactics for lowering project cost or project risk. Then, the analysis can be presented to the private entity, used to estimate the subsidy, and fleshed out when negotiating the final agreement.

Notes

1 The reader may wonder why reference is not made to the highest and best use of the site. Highest and best use in property appraisal calls for the identification of the most economically profitable use given legal and physical constraints (Appraisal Institute 2008). Most fitting and appropriate use is a broader concept that requires attention to collective users and even future users as well as current private users who are willing to pay market rents to occupy the property (Malizia 2009; Vandell and Carter 2000).

2 Soft costs include architectural and engineering fees and fees resulting from legal work, accounting, surveying, land planning, appraisal, market research, and marketing. Costs associated with the construction loan are included; construction-period interest is an important line item. All costs incurred to take the project through the development review process (entitlement process) are added, such as fees, cost of impact studies, community relations efforts, etc. Contractor fees, overhead, and contingency can be listed under soft costs but are often built into the hard cost estimates. Soft costs also include the developer fee (profit) and project contingency. The size of the latter reflects the perceived risk of the redevelopment. In private suburban projects, soft costs may be less than 25% of hard costs, but in complex urban redevelopment projects they can exceed that benchmark.

3 The ill-fated urban renewal program of the 1950–60s relied on eminent domain to condemn private property, assembled parcels into development sites, and sold these sites for nominal consideration. Public entities can contribute the land for redevelopment projects following this tradition. If the site is improved, the structure can also be contributed, but this may be both expensive and unnecessary. The developer may prefer to incur the cost of the building if historic preservation tax credits are envisioned. (When the developer purchases the building, it becomes part of the qualified basis used to calculate the tax credit.)

4 Of course, providing infrastructure within public rights-of-way is not a project subsidy but rather one way the public supports private development (see chapter 7). The subsidy begins when infrastructure is extended onto the site.

5 FIA compares the net increase in revenues to the net increase in costs. Although the redevelopment site often generates some tax revenues and requires expenditures for public services, the absolute amounts are probably not large. In the FIA, the present value of public expenditures is compared to the present value of the taxes paid to determine whether the fiscal impact of the redevelopment project is positive, negative, or neutral.

For infill sites in central areas, the redevelopment project will require public services. All uses will require police and fire protection, general governmental services, roads, utilities, etc. Projects with residential components additionally require social services, public schools, and parks and open space. Large-scale projects may well generate the need for new facilities and require additional capital outlays.

The people and businesses occupying the redevelopment project would pay municipal and county taxes downstream. In almost all states, they would pay ad valorem property taxes and sales taxes. In some areas, personal income taxes are also assessed at the local level.

6 Tax Increment Financing (TIF) is a popular way to afford subsidies to urban redevelopment projects. The property taxes forthcoming from redevelopment are dedicated to the project. Formal TIFs often float debt to finance infrastructure and then use the tax revenue stream to repay the debt. But TIFs can be used to subsidize the project directly with public support in lieu of property taxes. Informal TIFs (synthetic TIFs) can be established by mutual agreement as part of a public-private partnership and used as a source of public subsidy.

7 For example, government securities pay a return that is usually considered the risk-free rate. Other investments yield higher returns because the investor assumes more risk. General obligation bonds that are backed by jurisdictions offer lower yields than the revenue bonds because risk is less.

8 This situation is similar to differences in risk assessment among commercial lenders based on their prior experience. For example, lenders in Texas and Oklahoma are comfortable making loans for oil and natural gas exploration because they have become very familiar with that industry. Lenders without this experience would certainly shy away from these lending opportunities.

9 Project value increases when estimated NOI is divided by a lower cap rate that reflects lower return requirements.

10 The most risky stage of the development process is after the CO is issued but before the project has reached the occupancy level required by the permanent lender (stabilized occupancy). The developer seeks to increase occupancy as rapidly as possible, since the project is paying interest on the entire construction loan during this period. The public entity may be able to help market the project, but this risk is borne by the developer partly to justify his or her fee.

11 Once the private developer is selected, it is important to ensure that it will be able to carry out the redevelopment project. If the partnership is not properly structured with the appropriate lead public agency, another developer may be able to take over the project by making a nominally more attractive financial offer after all of the feasibility work and technical studies are completed (called an upset bid).

12 General contractors are learning how to reduce energy consumption during the construction process and from the materials and equipment employed. Techniques range from using locally sourced or recycled materials to worker training that reduces waste. Energy-efficient fixtures and materials are being used with greater frequency. Some projects using solar power or other non-petroleum-based sources of power are aiming to add energy to the grid on a net basis. Site development is another way to conserve resources and mitigate environmental impacts. Innovative techniques are being used for storm water management. Projects are increasingly collecting rainwater and using this gray water in place of potable water. Furthermore, urban redevelopment itself is more sustainable than new greenfield development, due to the embodied energy in existing buildings that are reused rather than replaced with new construction. (For an introduction to the topic and guide to the literature, see Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta 2009).

13 In addition to lowering financial risk through more conservative underwriting, commercial lenders often try to lower their financial exposure further by including their Community Development Corporation (CDC) subsidiary, since bank CDCs often have the contacts needed to bring public and private financing sources together for redevelopment projects.

14 Developers often reduce the holding period and financial exposure of equity investors through refinancing. If the redevelopment project is successful, it should generate more NOI and before-tax cash flow over time, which should increase project value. As debt service reduces the principal balance of the loan, equity builds in the project. Project owners can usually refinance the higher-valued project at a higher loan-to-value ratio than the ratio used for the original loan, often loan-to-cost. As a result, the owners receive the portion of the refinancing left after the principal balance of the original loan is paid, which is used to reduce investors’ financial exposure or even buy one or two out of the project.

15 It should be noted that private developers who are attracted to public-private urban redevelopment projects tend to be less experienced, because more seasoned developers are able to pursue projects that are less complex, less time consuming, and potentially more profitable. Moreover, newer developers want to build their reputations; carrying out a highly visible redevelopment project often leads to recognition at the local and regional levels. However, major, wellestablished real estate developers do participate in urban redevelopment. Their participation is correlated with downturns in the building cycle when private development opportunities become limited.

16 In essence, more variation in expected returns translates into higher risk premiums. For elaboration, see Luscht, 1997, chs. 14-15.

17 This proposal is not meant to deemphasize the importance of long-range master plans. In some jurisdictions, the master plan may be sufficiently detailed to lessen the need for small-area plans. In these cases, it would certainly be more cost effective to forego small-area planning. However, in many places, small-area planning is essential to flesh out the preferred uses of land within districts and corridors. The cost is usually justified because portrayal of small-area plans in three dimensions adds valuable information that is rarely presented in master plans.

18 Projects have been justified not through market research but on the belief that supply will create its own demand (build it and they will come). Usually, this belief is dashed by market realities.

References

Adair, A., S. McGreal, B. Deddis, and S. Hirst. 1999. “Evaluation of Investor Behaviour in Urban Regeneration.” Urban Studies 36(12): 2031-45.

Appraisal Institute. 2008. The Appraisal of Real Estate. 13th ed. Chicago.

Blakely, E. J., and N. Green Leigh. 2010. Planning Local Economic Development: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

Ciochetti, B. A., and E. E. Malizia. 2000. “Ch. 8: The Application of Financial Analysis and Market Research to the Real Estate Development Process.” In Essays in Honor of James A. Graaskamp, ed. J. DeLisle and E. Worzala. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 135-65.

Dermisi, S. V. 2009. “Effect of LEED Ratings and Levels on Office Property Assessed and Market Values.” Journal of Sustainable Real Estate 1(1): 23-47.

Donegan, M., J. Drucker, H. A. Goldstein, N. J. Lowe, and E. E. Malizia. 2008. “Which Indicators Explain Metropolitan Economic Performance Best?” Journal of the American Planning Association 74(2): 180-95.

Fanning, S. F. 2005. Market Analysis for Real Estate. Chicago: Appraisal Institute.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. 2009. “Green Development Primer.” Special Issue. Green Partners in Community and Economic Development 19(2).

Feser, E. J., and E. E. Malizia. 1999. Understanding Local Economic Development. New Brunswick, NJ: Center for Urban Policy Research.

Florida, R. 2004. Cities and the Creative Class. New York: Routledge.

———. 2005. The Flight of the Creative Class. New York: HarperCollins.

Frieden, B. J., and L. B. Sagalyn. 1989. Downtown Inc: How America Rebuilds Cities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gordon, D. L. 1997. “Financing Urban Waterfront Redevelopment.” Journal of the American Planning Association 63(2): 244-65.

Graaskamp, J. A. 1981. Fundamentals of Real Estate Development. Development Component Series. Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute.

Gyourko, J., and W. Rybczynski. 2000. “Financing New Urbanism Projects: Obstacles and Solutions.” Housing Policy Debate 11(3): 733-50.

Hodge, G. 2004. “The Risky Business of Public-Private Partnerships.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 63(4): 37-49.

Jackson, T. O. 2001. “Environmental Risk Perceptions of Commercial and Industrial Real Estate Lenders.” Journal of Real Estate Research 22(3): 271-88.

Kotin, A., and R. Peiser. 1997. “Public-Private Joint Ventures for High Volume Retailers: Who Benefits?” Urban Studies 34(12): 1871-1997.

Leinberger, C. B. 2005. Turning Around Downtown: Twelve Steps to Revitalization. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Luscht, K. M. 1997. Real Estate Valuation. Chicago: Richard D. Irwin.

Malizia, E. E. 1997. Economic Development Finance. 2nd ed. Rosemont, Illinois: American Economic Development Council.

———. 1999. “The Garvey Retail Center Case: Redeveloping an Inner-City Site.” Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education 2(1): 63-120 and teaching notes.

———. 2003. “Structuring Urban Redevelopment Projects: Moving Participants Up the Learning Curve.” Journal of Real Estate Research 25(1): 463-78.

———. 2009. “Site Use in a Redeveloping Area.” Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education 12(1): 81-104.

Malizia, E. E., and J. Accordino. 2001. Financing Urban Redevelopment Projects. Community Affairs Office, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Research Report.

Meeker, L. 1996. Doing the Undoable Deal. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Monograph.

Meyer, P., and T. T. Lyons. 2000. “Lessons from Private Sector Brownfield Redevelopers: Planning Public Support for Urban Regeneration.” Journal of the American Planning Association 66(1): 46-57.

Miller, N. G., D. Pogue, Q. D. Gough, and S. M. Davis. 2009. “Green Buildings and Productivity.” Journal of Sustainable Real Estate 1(1): 65-89.

Sagalyn, L. B. 1997. “Negotiating for Public Benefits: The Bargaining Calculus of Public-Private Development” Urban Studies 34(12): 1955-70.

———. 2007. “Public/Private Development: Lessons from History, Research, and Practice.” Journal of the American Planning Association 73(1): 7-22.

Sawicki, D. S. 1989. “The Festival Marketplace as Public Policy.” Journal of the American Planning Association 55(3): 347-61.

Vandell, K. D., and C. C. Carter. 2000. “Ch. 15: Graaskamp’s Concept of Highest and Best Use.” In Essays in Honor of James A. Graaskamp, ed. J. DeLisle and E. Worzala. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 307-19.

Wood, J., and N. Wood. 1985. Financial Markets. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.