The creators and contributors of SynergiCity share the following points of general consensus:

We are pro-development.

We are pro-density.

We are pro-community.

We are pro-environment.

We are pro-sustainability.

We believe in the heritage of the built place.

We believe in large-scale visioning.

We believe in small-area revitalization.

We are against development centered on the automobile.

SynergiCity is, in fact, the product of synergy. More than just an area of architecturally rehabilitated buildings, it is the transformation of dormant factories and warehouses into inviting attractors of small businesses, incubators, offices, retail shops, green public places, and residences. It is the result of five distinct environmental design professions (architecture, planning, historic preservation, landscape design, and urban design) and cities working together to produce a singular vision addressing postindustrial urban redevelopment that is far greater than the individual visions of each entity. It is the culmination of the meeting of industrial heritage with nature, architecture with social economics, and urban revitalization with environmentally sustainable design. It is a city-within-a-city, a neighborhood for residents, a destination for shoppers, and a community for creative entrepreneurship. It is the ideal postindustrial community of the twenty-first century comprised of the creative capital of economy, marketable talent, and industrious people.

Manufacturing began in the Midwest in the late nineteenth century with significant industrialization occurring between 1860 and 1920 (Meyer 1989). This industrial maturation resulted in large factories built to produce more goods, mostly built between 1890 and 1940. Manufacturing in the United States began to decline in the 1970s. During the 1980s corporate takeovers precipitated this decline; in the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century, manufacturing began its current steep decline as globalization took hold in the world economy. Nearly every city in the Midwest has been affected by this change. Cities such as Cleveland and Youngstown, Ohio; Detroit and Flynt, Michigan; and Elkhart, Indiana, have lost significant portions of their populations as more and more people have left former manufacturing cities for work elsewhere (McCormack 2010). Today, warehouses sit empty, factories are shuttered, and smokestacks, once towering symbols of industrial might, are reduced to either nostalgic relics or rubble. This book not only presents the case for their preservation, but provides direction for their redevelopment as a base for the twenty-first century and green economy, the theoretical core of SynergiCity.

Postindustrial redevelopment is hardly new; it is even older than the term “postindustrial,” as Daniel Bell dubbed it in 1973. Originally, such redevelopment was considered part of the fringe element of American culture; artists, low-level retail, and ethnic groups, such as first-generation immigrants, engaged in this kind of development, since “normal” development (central business districts in cities) and use of urban space was cost prohibitive to them (Jacobs 1961). Today, transformed districts such as Milwaukee’s Third Ward, the Minneapolis Warehouse District, and Lowertown in Saint Paul are, after 30 years of intensive work, once again serving the economic needs of the city. These successes, combined with today’s sustainable culture of reduce, reuse, and recycle, make the case for rehabilitating postindustrial districts an easy one. The utilization of these historic existing buildings and the reuse of their materials for living and working keeps viable materials out of the landfill and keeps the production of new raw materials at a minimum. The vastness and size of these districts will accommodate the need for space required in small-batch manufacturing. All of these factors will help keep the new industry ideas alive in the Midwest despite the effects of the Great Recession.

Manufacturing continues to be a vital component of the economy of midwestern cities. Within one year after the mass layoffs of employees of Caterpillar in 2009, Peoria was still ranked by Money as one of the best cities in the United States to start a small business (Tarter 2010). Sometimes unemployment of skilled workers can give rise to new industries, such as the production of wind turbines for green energy, medical devices for the expanding biotech market, and agricultural equipment for agribusiness, an industry started in Peoria by Caterpillar’s former middle management. Small, innovation-based companies such as these are emerging in the postindustrial Midwest — precisely the shift to creative and innovation-based jobs that Richard Florida calls the “Great Reset” (Florida 2009). With its flexible infrastructure, vast amounts of space, visual and historic character, and location near central business districts, the postindustrial district can be redeveloped to become environmentally sustainable, pedestrian friendly, and the ideal location for these twenty-first-century businesses (plates 2 and 3). It is precisely this type of major transformation the district must undergo if it is to survive the shift from manufacturing sector jobs to service sector jobs, which the American economy is currently undergoing, as described by Mark Gillem in chapter 7. Today, very few postindustrial districts are being used as centers for innovation businesses. Cities such as Rockford, Illinois (fig. 14.1), and Elkhart, Indiana, need to “reset” their postindustrial districts (McCormack 2010).

However, before midwestern cities “reset,” they should reconsider, analyze, and plan their postindustrial districts for a new and productive future that will generate highly valued technologies, experiences, products, and services. Rather than being based on simply mechanical production, the new, innovative economy of the twenty-first century will be powered by imagination, creativity, and teamwork. In order for it to thrive, it requires a highly educated and motivated workforce, institutions of higher education (for training and business collaboration), and buildings and places that are conducive to human interaction and collaboration. Postindustrial districts revitalized in accordance with the concept of SynergiCity have the attributes to attract the highly educated and creative minds needed for the innovation economy to emerge. The challenge is the transformation of the postindustrial district for the new economy.

This book answers this challenge by presenting one viable option for economic renewal through the rebuilding of the industrial districts of midwestern cities. Each of our contributors has proposed ideas to help facilitate the redevelopment of buildings, underground infrastructure, and streets with the creation of public parks and plaza spaces. Their ideas also address immediate and broader challenges facing America today, including unemployment, poor air quality, declining real estate values, addiction to fossil fuels, suburban sprawl, and an impending lack of potable water.

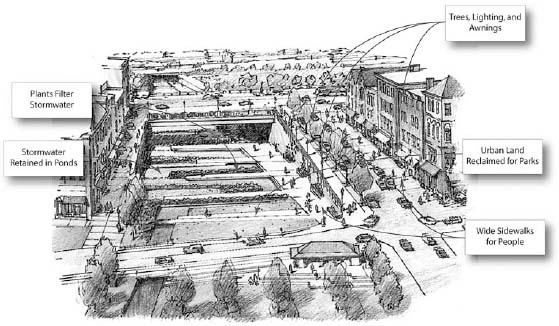

The SynergiCity idea of postindustrial urban redevelopment is a three-part approach, ecological, interactive, and adaptive. This approach strives to renew the urban ecology as it redevelops the postindustrial district (fig. 14.2). An interactive approach, it proposes active environments that emphasize walking and active living, pedestrian movement instead of automotive movement — all of which stimulates social interaction and provides environments that aspire to do more than be engaging and instead to become “environments that educate.” Finally, the SynergiCity approach embraces the industrial heritage of the postindustrial district. Through adaptive use, it seeks to transform large buildings that have a vast amount of adaptable, useable space and robust structures for new uses that complement the original character of the buildings.

SynergiCity begins with ecological design. In the Midwest, potable water must be a major criterion in urban redevelopment, especially in attracting new innovation-based “green” industries and a creative, well-educated workforce. Water certainly attracted industrialists well over a century ago, who used it to provide transportation systems for people and manufactured goods in Rockford and St. Louis, to manufacture whiskey in Peoria and beer in Milwaukee, and to generate power for mills such as the St. Anthony Falls in Minneapolis — and water continues to attract industry today. The Midwest is blessed with the largest bodies of freshwater (the Great Lakes) in the world, the great Mississippi and Ohio rivers, and aquifers full of high-quality fresh water. Mercer, a global human resource and financial consulting firm that provides rankings produced exclusively to inform top companies and their top talent which cities are the most livable, has taken note. In Mercer’s first “Eco-City” ranking of the most environmentally friendly cities in the world, Minneapolis ranked sixth and St. Louis ranked forty-third. The criteria for this ranking included water availability, water portability, waste removal, sewage, air pollution, and traffic congestion. Water is now not only a public health issue but also an economic development and marketing issue: mayors, city administrators, and public officials should make the availability of potable water a priority as they plan for future development, since companies today consider a city’s commitment to environmental stewardship a criterion for location.

For the past 15 years, water experts throughout the Great Lakes region have been concerned about the future of potable water (Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant 2010). The value of this precious resource increases even more as sources from aquifers around the United States are now being used at a faster rate than they can be replenished, especially in areas that lack large bodies of fresh water such as the Southeast and Southwest (Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant 2010). In chapter 1, Don Carter correctly sets the ecological tone when he recodifies these regional disparities in America by redefining former “rust belts” as “water belts” and so-called sun belts as arid “drought belts.” Thus, he maintains, in the twenty-first century a potable water source will no longer be continual. If water becomes a finite resource and as precious as oil in the twenty-first century, then the states that border the upper Great Lakes are likely to be the new “OPEC of water.” Therefore, planners and government officials all throughout the Midwest where fresh water is abundant should take note of the future economic and ecological potential of potable water.

Potable water, the environment, and their relationships to the SynergiCity approach have been discussed in a variety of ways by contributors Christine Scott Thomson, James Wasley, and Mark Gillem. Together they present a common overarching urban, landscape, and design vision that can best be called Ecological Urbanism. At the heart of this design theory is a fundamental belief that the Earth is indeed a closed system. As we design with the SynergiCity approach, a new balance between natural systems and urban systems must be established. Thomson proposes an urban-scale ecological solution that protects natural estuaries and tributaries of waterways that provide the filtration of storm water before it enters rivers or lakes. By relating the natural role of an urban greenway (which is based on estuaries and tributaries) to its recreational use in the city, she proposes the greenway as a primary urban feature for the city. Redeveloping natural spaces in and adjacent to postindustrial districts can benefit the city in three ways: (1) improve the water quality, (2) improve the natural habitat of the city, and (3) provide recreational venues for all citizens. Using the proposed nearly 900-acre Milwaukee River Greenway Master Plan as a case study, Thomson presents an idea for midwestern cities that celebrates the heritage of the postindustrial city and its historical relationship to the waterways and estuaries that provide havens for wildlife and fauna. These parks can also become a recreational venue in the city with nature walks, playing fields, and rowboat opportunities. There are numerous benefits of the large-scale park and nature sanctuary in the SynergiCity approach. As Thomson states in chapter 9, the greenway can “connect people with places, both natural and human-made, connect past to present, and bring the boater into contact with the rivers and surrounding lands.”

FIGURE 14.1. The Barber Colman Factory sits idle along the Rock River in Rockford, Illinois. Without public-private investments buildings like these will deteriorate further, resulting in higher land reclamation and new construction costs in the future. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

FIGURE 14.2. Ecological redevelopment of underutilized urban areas for parks can enhance the city aesthetically. (Courtesy of U.S. Pipe/Wheland Foundry and LA Quatra Bonci Associates/Edward Dumont)

Brownfield remediation should occur regardless of use. Pollution resulting in contaminated soil and water has and will continue to be a significant challenge in the redevelopment of postindustrial sites. As we reconsider what is left on these sites after industry has discarded them for cheap labor and fewer restrictions overseas, we must plan now not only for their remediation but also for their redevelopment and reintegration into the city. In chapter 7, Mark Gillem asserts that environmental remediation of brownfield sites, which is necessary for clean groundwater and public health, can also serve as the catalyst for the betterment of the public realm. For example, Gillem showcases the remediation of contaminated sites in the Pearl District in Portland, Oregon, which allowed recyclable infrastructure to be reutilized and existing industrial buildings to be adapted for new uses. This can have two significant benefits: sites that should never have originally been developed can become parkland and nature sanctuaries, and the district’s buildings and infrastructure (streets, alleys, and rail lines) can be redeveloped.

Development in the postindustrial district should be done in a “closed-loop’’ manner. Storm water removal should equal a site’s predevelopment rate of stormwater runoff. Simply diverting storm water into large pipes and sending it to natural waterways is no longer a responsible or feasible option. In chapter 8, James Wasley proposes developing a “Zero-Discharge Zone” (ZDZ) for the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee as a sensible ecological design strategy for storm water management. All urban districts, especially midwestern postindustrial ones with their proximity to large waterways, should not only retain but also recycle their storm water, using design strategies ensuring that the water discharged from the district be as clean as possible. By implementing best management practices for storm water management, thoroughly remediating postindustrial sites, and achieving a regional vision of greenways, the industrial heritage of the city and nature can coexist in “SynergiCity’’ (plate 2).

Unfortunately, incentives for new site development in cities today often discourage this type of sustainable redevelopment and the emergence of a “SynergiCity.” As Gillem states in chapter 7, cheap land, access to interstate highways, and cheap financing encourage developers to build on greenfields and abandon brownfields. The magnitude of effort and expense coupled with the liability of remediating brownfield sites is enough to discourage any developer to engage in such a daunting project. In chapter 6, John Norquist, CEO of the Congress of New Urbanism, proposes a clear line of demarcation between the responsibilities of the public and private sectors in the redevelopment of postindustrial districts. The public sector should take on the task of remediation, which includes upgrading the infrastructure of utility and sewerage services, while the private sector should redevelop the buildings and sidewalks. In his opinion, tax incremental financing (TIF), a current governmental program that communities use to promote private development through capturing the projected property tax revenue stream created by the development and investing those funds into the district that is being redeveloped, should be discouraged and used as a last resort. This way, public financing directly serves the public realm and private financing directly benefits the investor (Norquist 2010). This is not to say that federal and state programs such as the federal and state historic preservation tax credits or low-income tax credits and enterprise zone tax incentives should not be used; these are proven effective tools for urban redevelopment. But by clearly defining the role of the municipal government in development, the perception that some property owners are paying more taxes than their neighbors could be avoided. This perception has and will most likely continue to be a stumbling block for postindustrial district redevelopment. Until recently, environmental remediation did little to attract private investment in postindustrial redevelopment, but this is also beginning to change. As always, the market influences development. In today’s green-based economic environment, investors are attracted to what an environmentally sensitive postindustrial redevelopment can offer. People who are interested in building a business or relocating their residences are taking note of this new kind of development, its synergy between nature and industrial character, and its sense of “totality” through its diverse social, economic, and environmental opportunities in harmony with the natural and urban environments.

FIGURE 14.3. The interior of the Deere & Company building in Minneapolis combines existing materials with new, upscale elements. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

Midwestern postindustrial cities are, for the most part, entire and intact. From Milwaukee to St. Paul and Peoria to St. Louis, these districts convey a sense of “wholeness,” making them compelling places to restore and develop (fig. 14.3). The existing architectural and urban conditions found in postindustrial districts present exciting design opportunities. High-end architectural design, sustainable and ecological design, and historic preservation are but a few areas that can be explored in these districts. The pedestrian nature of the midwestern postindustrial district and the immense size of the warehouse districts are two significant attributes that can make “SynergiCity” a reality. While reinventing blocks of warehouse buildings, streets, alleys, and waterfronts, the design principles of Amble, Density, Sustainability, Epicenters, and Synergy (developed by the Peoria design studios at the University of Illinois and described in greater detail in chapter 2) did not seem so difficult to determine (plates 2 and 3). In fact, they were almost self-evident, since warehouse districts such as the one in Peoria were built with these ideas in mind. As Norquist observes: “There is nothing wrong with the warehouse district. It does everything we want a city to do” (Norquist 2010). Norquist is right. The pedestrian scale is intact, with streets and alleys originally built to accommodate large amounts of traffic. Existing warehouse buildings can be economically adapted to a wide variety of new uses. And the district’s inherent “grittiness” attracts a new “creative class” of artists and entrepreneurs.

In the past, accommodating large numbers of automobiles in postindustrial districts has been perceived as an obstacle. Instead of designing transportation systems to move automobile traffic as quickly as possible in and out of a district, a new approach to transportation design should be used that enhances the district’s sense of place and takes advantage of all of the attributes the existing transportation system offers, including wide streets, alleys, and on-street parking. In chapter 10, Norman Garrick proposes a “city-friendly” transportation planning approach that sets “maximum,” not “minimum,” parking requirements for developments and advocates that once the maximum amount of parking spaces has been reached in the district, postindustrial districts should then implement “nonauto” forms of transportation (mass transit, bicycle lanes, and parking racks). Garrick’s “city-friendly” approach promotes healthier lifestyles for people who live in the urban district as well as enhancing its historic character (fig. 14.4).

FIGURE 14.4. New infill development resides with old in the Warehouse District of New Orleans. The character of the district is maintained through the creative use of modern industrial materials. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

Interestingly, the postindustrial district is the place where diverse and disparate design theories and philosophies converge — a synergy of architecture, preservation, landscape design, planning, and urban design. The variety of inventive design and well-planned historic preservation occurring in successfully redeveloped districts is impressive. In these successful redevelopments, New Urbanism can work hand in hand with Ecological Urbanism. Historic preservation can work with new design. Traditional or contextural architecture can coexist with the historic landmarks of the district. “Edgy” modern design fits within the old blocks of masonry warehouses. Although districts such as Milwaukee’s Third Ward have begun to enforce stricter design guidelines, essentially the use of New Urbanist “SmartCodes” and a respect for the context of street wall and building massing is sufficient for architectural expression to flourish in these districts (plate 1). Part of this reasoning is that historic warehouses in the Midwest were built with both utility and tradition in mind. Most embody traditional and classical proportion (a clearly delineated base, middle, and top composition), but they were also built using modern and industrial materials and elements including large steel framed windows, steel fire doors, and concrete structural systems — component assemblies that inspired European modernists of the early twentieth century. This architectural link between traditional and utilitarian design found in older historic warehouses allows for a visual compatibility between old and new buildings to occur. Whether it is the detailing of new against old found at the architecture offices of PSA-Dewberry in Peoria or the rooftop expansion of the old port building in the Milwaukee Third Ward, it is clearly apparent that the opportunities for interesting and innovative architecture can happen in SynergiCity.

It is also interesting to note that design expression in these districts is not necessarily prescribed by design guidelines, as one would typically encounter in a typical historic district, but is inferred by the preservation and architectural ethic of a particular city. A good example of this dichotomy of ethics can be found when comparing St. Paul to Minneapolis. In St. Paul, preservation and rehabilitation of the historic warehouses strictly followed the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation. The building of new townhomes and commercial spaces in St. Paul tended to be contextural, with new buildings designed to match the existing historic buildings. Redevelopment in Minneapolis’s warehouse district took a different approach. New buildings, comparable to any new modernism found anywhere in the world, are juxtaposed with historic warehouse buildings. The warehouses were transformed at the roof level with the addition of new units and roof terraces. Both approaches accomplish the same objective: the transformation of an unused industrial district into an enriching place to experience, at the same time respecting its historic character. This spatial arrangement and density of buildings found in the postindustrial district allows the dynamic urban phenomenon of “Urban Metabolism” to occur in the city. Urban metabolism is best defined as the ability to facilitate productive technical product-based economic enterprises and socioeconomic processes, resulting in urban growth, the production of social energy, and the elimination of organic and inorganic waste (Kennedy et al. 2007). Urban metabolism is essential for SynergiCity to become a reality. European cities such as Vienna, Helsinki, and Copenhagen are well known for their improved Urban Metabolism, which is the result of improved efficiency of mass transit, active lifestyles, and social interaction, all of which enables cities to be more productive, produce less waste, and consume less energy.

The redevelopment of postindustrial districts is a long and arduous process. This is clearly evident in the Lowertown district in St. Paul, where Weiming Lu, executive director of the Lowertown Redevelopment Corporation, spent 30 years of his long and illustrious career rebuilding and preserving that district. He planned the Lowertown redevelopment one block at a time, allowing successful projects to build off each other. Each of these small-area development projects was based on a broader vision: to transform Lowertown into a vibrant urban village within St. Paul (Lu 2010). In chapter 13, Emil Malizia presents a practical approach to implementing development through small-area revitalization, improving the infrastructure in the same small areas, doing emergency structural stabilization projects when it is necessary, and finally promoting competition within the development community. This approach has been proven successful throughout the Midwest in developments such as Midtown Alley in St. Louis. In 2003, local developer Renaissance Development Associates began a redevelopment project in a concentrated small area of abandoned historic automobile factories and sales buildings that once supported St. Louis’s short-lived automobile industry of the early twentieth century. By concentrating on an eight-block area near St. Louis University, the developers have been able to build their success one city block at a time, resulting in over $70 million of redevelopment in a seven-year span (Johnson 2010). Aside from the financial attributes of this approach, there are a number of architectural and urban facets to it as well. By implementing small-area planning, primarily through preservation development, the critical first phase of a long-term, large-scale urban redevelopment can be achieved. Malizia’s implementation approach, combined with initial broad visioning planning as suggested by both Carter and Thomson, is the key to making SynergiCity a reality. It can be developed block by block, with each small success story leading to a larger project, all of which is carefully coordinated to fulfill a common vision for redevelopment.

The timing of this book is also worth noting, because postindustrial districts throughout the Midwest are in various stages of redevelopment. Postindustrial districts in Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and St. Paul can now be considered redeveloped after 30 years of planning and construction. These districts are now considered successful, with new and rehabilitated buildings that have been recognized for their innovation and have received architecture, historic preservation, and sustainability awards. However, it is worth noting that once redeveloped, postindustrial districts can become victims of their own success. They can become too expensive for starting businesses or creative individuals such as artists to afford. The rise in property values and taxes that gentrification brings can stifle the innovative spirit in a district. Innovation needs to be served by both a diversity of productivity yields and a diversity of people from all income brackets and ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Simply assuming that the market or the private sector will provide affordable residential and commercial space is naive; moreover, local government mandating a percentage of affordable housing units or commercial suites in a development project does not always ensure that a balance of income levels can be achieved within a district. However, another type of developer can serve this need to ensure that the economic diversity of a district is preserved: the nonprofit corporation and the charitable foundation. Throughout the United States, nonprofits have played a positive role in postindustrial redevelopment. In Milwaukee’s Fifth Ward, CommonBond, a Minneapolis-based nonprofit affordable housing developer, rehabilitated the 11-story Teweles Seed Warehouse building into a new mixed-income apartment building (fig. 14.5) (Jones 2010). Rents varied in the building from small efficiencies starting at $300 per month to the penthouse at $2,500 per month. Nonprofit developers can pool together private and public funding sources; they can solicit investors, leverage equity, qualify for Department of Housing and Urban Development funding, and even use preservation tax credits.

Figure 14.5. Common Bond, a nonprofit developer, rehabilitated the 11-story Teweles Seed Warehouse building in Milwaukee’s Fifth Ward into a new mixed-income apartment building. (Courtesy of Paul J, Armstrong)

For the past 60 years, philanthropy from charitable foundations has made an immense impact in urban redevelopment. For instance, the Heinze Foundation helped to finance the redevelopment of the warehouse districts of Pittsburgh. Lowertown in St. Paul would have never been redeveloped without the initial $10 million contribution from the McKnight Foundation, and it was the generous support of the Lyndhurst Foundation that enabled the Chattanooga, Tennessee, riverfront to undergo a green rehabilitation. By bringing corporate foundations and nonprofits into the earliest stages of postindustrial redevelopment, their missions become integrated with the overall goals of redevelopment. Whether the mission is to provide affordable housing, space for startup businesses, or sustainable development, everyone benefits when the missions of nonprofit entities and foundations become a physical reality.

While a vision of sustainable community development, the use of less fossil fuel, and the promotion of healthier lifestyles are all compelling reasons to redevelop postindustrial districts, clearly the most important one is the need to increase economic production in cities. Despite predictions that the internet would decentralize industry, the opposite is, in fact, occurring. A 2007 World Bank report on productivity determined that productivity and performance is higher in urban areas (World Bank 2009). Creativity and innovation rarely occur in isolation; urban areas have always brought together and multiplied human productive efforts. Noted urban theorist Jane Jacobs asserted 50 years ago that the agglomeration of human capital is essential for innovation to occur. Placing creative enterprises in structured research parks, the prevailing development model in the postwar era, is both inefficient and inconvenient. As I wrote in chapter 3, the mixing of businesses and live-and-work experiences with aged buildings allows for a development to become dynamic. It provides businesses room to expand while at the same time minimizing expense by reusing existing buildings.

Figure 14.6. Designed by architect James Shields of Ellerbee Becket, Marine Terminal Lofts in the Third Ward District, Milwaukee, integrates new high-end penthouses into the exterior shell of a former port terminal building. (Courtesy of Paul J. Armstrong)

The Marine Terminal Lofts in the Third Ward District of Milwaukee, for example, integrate new high-end penthouses into the existing shell of a former port terminal building (fig. 14.6). Designed by architect James Shields of Ellerbee Becket, the Marine Terminal Lofts bring urban living directly to the shore of the Milwaukee River. Adaptive reuse projects like the ones described allow a new cycle of innovation to begin in stagnant urban districts.

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs gives an example of how businesses typically start and grow in New York. Two mechanics in Brooklyn quit their jobs working in a factory and open a business in one of their garages. The business grows, and they move into a larger building. Finally, they build a large plant in New Jersey. Whereas Jacobs’s example of free enterprise occurs in New York and New Jersey, it is essentially the story of how businesses grow throughout the United States. While it is true that a business will sometimes outgrow its building, it is the hope that it will not outgrow its community of innovation. “SynergiCity” can be the host for this innovative community as a granary of old and new buildings capable of accommodating enterprises at all stages of growth and development. By adapting old buildings for new uses and adding compatible new ones within the existing urban fabric, a city can make a warehouse district once again serve the city’s economic needs. Unlike the research park that caters only to manufacturing, such a district is the place where residential living, manufacturing, and research and development occur simultaneously (plates 4 and 6).

Current market trends should also be considered within the context of sustainable urban development. “Green” developments are being built and successfully marketed. Developments such as Dockside Green, a 15-acre luxury development located in a brownfield in Victoria, British Columbia, employs a number of the ideas presented in this book. It mixes Victoria’s industrial character with green living, combining both living and work areas, and preserves the waterways, which are also used for recreation. These features helped sell units in the development at prices ranging from $400,000 for a one-bedroom condominium to over $1 million for penthouses. Dockside Green, a product of brownfield mitigation and sustainable design, is proof that individual investors are interested in the postindustrial district development: SynergiCity is not just a theoretical idea; it’s marketable and it sells (Baker 2010).

We do not believe that the SynergiCity approach can solve all of the problems facing midwestern cities today. We also do not believe that everyone will want to move to a redeveloped warehouse district in Peoria and completely change their lifestyle. There will always be suburbs, and there will always be people who prefer to live in a detached residence, enjoy a large residential lot, commute by automobile to work, and shop in retail shopping centers. However, before we use limited resources to develop rural land for suburban development, we should fully maximize the underutilized resources that postindustrial districts and historic city centers offer.

Redeveloping postindustrial districts is a challenge that requires a true synergy of diverse design professions and ideas if it is to be successful. Developers will be successful in these ventures if they take a holistic approach that incorporates urban design, planning, architecture landscape design, and historic preservation. In cities throughout the Midwest, this is already happening. From Minneapolis to St. Louis, the redevelopment of both industrial heritage and naturally wooded greenspaces has produced exceptional results. We are optimistic that the Midwest will reset itself for a brighter future in a new economy. Rumors of the demise of its manufacturing capabilities have been greatly exaggerated, but innovation of new products and new ideas will henceforth be what is typically done in midwestern cities. Ideas and entrepreneurship have always happened in the Midwest and will continue in the foreseeable future throughout the region. The Midwest is blessed with a plentiful amount of potable water. Compared to regions such as the West Coast or the East Coast, housing and commercial real estate are still reasonably affordable, along with the overall cost of living. As my coeditor often asks: “Why should a breakthrough invention or idea that happens in Champaign, Illinois, be developed in Silicon Valley?” Cities like Peoria and Rockford should provide the buildings, parks, and recreational amenities that will lead this innovative talent to remain in the Midwest. These buildings and spaces already exist and were often built out of high-quality materials with exquisite design and craftsmanship. Rather than allow them to remain stagnant and decay further, we should reinvent them in ways that embrace their industrial roots for an environmentally sustainable future. Let’s create places where enterprise is welcomed — not places that the next Fortune 50 company necessarily relocates to but places from which it emerges. We are confident that the “innovation economy” will happen in the Midwest, and when it does, it will happen first in a place called SynergiCity.

References

Baker, L. 2010, July 7. “A Housing Project That Embraces a City and Nature.” New York Times.

Beatley, T. 1999. Green Urbanism: Learning from European Cities. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Florida, R. 2009, March. “How the Crash Will Reshape America.” Atlantic. Available at www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/03/how-the-crash-will-reshape-america/7293/.

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant. 2010. Water Supply. Available at the website of Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, www.iisgcp.org/topic_watersupply.html.

Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Johnson, J. (Renaissance Development Associates). 2010, July 14. Interview with the author at Renaissance Development, Midtown Alley District, St. Louis, Missouri.

Jones, P. (CommonBond Development Company). 2010, May 12. Interview with the author.

Kennedy, C. A., J. Cuddihy, and J. Engel Yan. 2007, May. “The Changing Metabolism of Cities.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 11(2): 43-59.

Marsh, M., G. C. Kroll, and O. Wyman. 2010. Mercer’s 2010 Quality of Living Survey Highlights — Global. Available at www.mercer.com/qualityofliving.

McCormack, R. A. 2010, March 31. “Dozens of U.S. Cities Lose Half Their Population in a Generation: A Record Last Set during the European Plague.” Manufacturing and Technology News 17(5). Available at www.manufacturingnews.com/news/10/0331/plague.html. Accessed September 29, 2010.

Meyer, D. 1989. “Midwestern Industrialization and the American Manufacturing Belt in the 19th Century.” Journal of Economic History 49(4): 921-37.

Norquist, J. 2010, May 17. Interview with the author at Congress for New Urbanism, Chicago.

Tarter, S. 2010, October 16. “Peoria a Great Place for Small Business: CNN/Money Names City 5th Best on Mid-sized List, 15th Overall.” Peoria Journal-Star. Available at http://www.pjstar.com/business/x988292039/Peoria-a-great-place-for-small-business. Accessed January 15, 2012.

Weiming Lu. 2010, June 25. Interview with the author.

World Bank. 2009. World Development Report 2009. Available at siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDR2009/Resources/Outline.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2012.