SADLY, MANY PEOPLE IMPORTANT to those early years of the National Ballet have died. This is not surprising, as it was so long ago, but their memories live on in the minds of those whose lives they touched. We are very grateful to them, and they should be remembered. To that end, I contacted several other luminaries from the dance community today to ask them to write a tribute to these champions of the past.

CELIA FRANCA EARLY YEARS

CELIA FRANCA WAS BORN CELIA FRANKS in 1921 in London, daughter of Polish immigrants. She began her study of dance at the age of four, studying at the Guildhall School of Music and the Royal Academy of Dance, as well as with Stanislas Idzikowski, the Polish ballet master; Judith Espinoza, the renowned dance teacher; and the English choreographer Antony Tudor. She joined the Ballet Rambert in 1936, and made her professional debut there at age fifteen, choreographing her first piece in 1939. In 1941, at age twenty, she danced and choreographed for the Sadler’s Wells Ballet and in 1947 became the ballet mistress of the Metropolitan Ballet. At this time, she began choreographing for television, creating Eve of St. Agnes and Dance of Salome for BBC. When Stewart James came to England in 1950, on behalf of a Toronto group who thought Canada was ready for a national ballet company, he met with Dame Ninette deValois, the Artistic Director of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. deValois recommended Celia Franca because of her many and varied strengths. deValois reportedly said that Franca was the greatest dramatic dancer the Wells ever had. At that time, Franca had been working in the world of ballet in London for fifteen years. In addition to her skills, she also had a network of contacts with dancers throughout Europe. Therefore, when developing her own company in Canada, she was able to invite them to perform. By the 1960s and 1970s, Franca was able to have stars such as Erik Bruhn and Rudolf Nureyev perform classical works for the National Ballet.

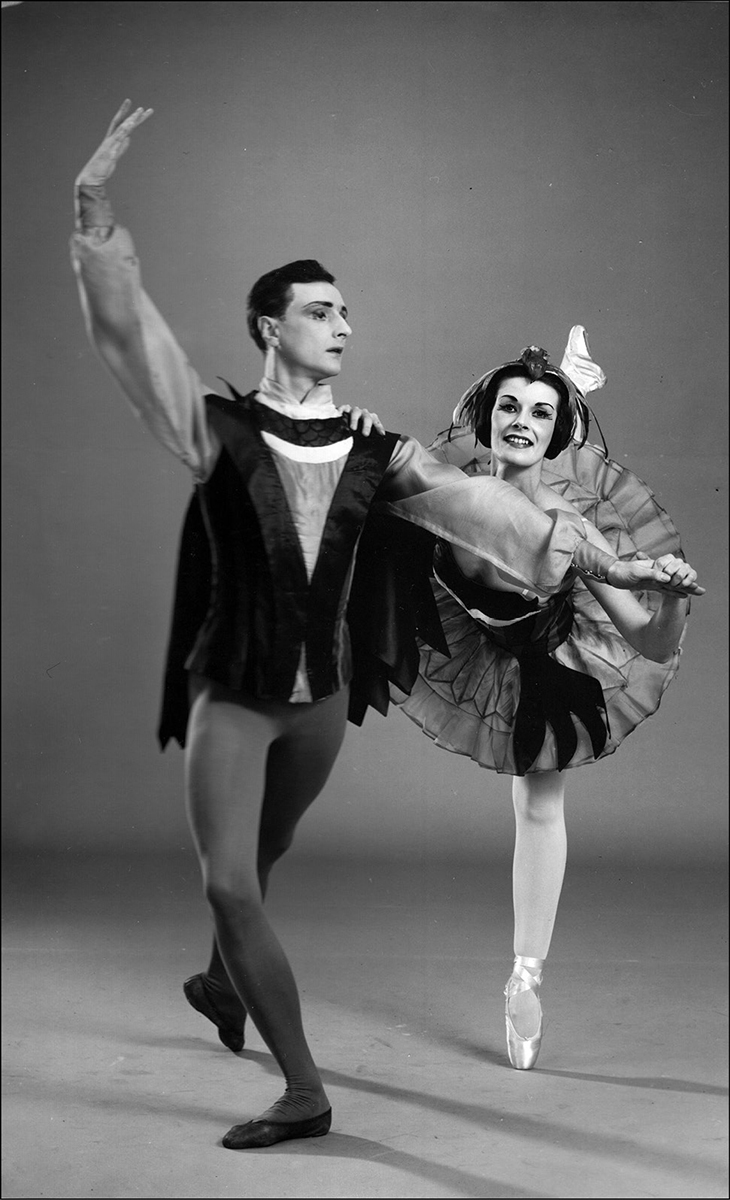

Marcel Chojnacki and Celia Franca in Coppelia, 1951. Photo: Kenneth J. Smith.

Courtesy: National Ballet Archives.

When she arrived in Toronto in 1950, the first thing Franca did was tour across the country to search for dancers. And she found them in various dance studios and community halls. Like Franca’s Polish parents, in many cases the parents of these up-and-coming dancers had emigrated from other parts of the world and brought their culture with them, and all cultures include music and dance. Some of Franca’s recruits came from the Polish and Ukrainian halls in Toronto. Others had been taking dancing lessons at the Boris Volkoff Studio. Some families were willing to move to accommodate their young child’s desire to dance and were willing to allow and enable them to join this unknown life, touring across North America for very little money. Some young men were themselves immigrants and determined to join the world of ballet. What trust they must have put in Celia Franca. In some ways, she must have seemed like the Pied Piper of Hamelin. But Franca had more than just a magic pipe.

She was elegantly attractive with her dark, kohl-lined eyes, swept-back black hair, and stylish wardrobe. She could dance, teach, direct, and choreograph. She could fundraise and work with a board of directors as well as supporters. With her dancers, she was strict and demanded nothing but the best. She could be cruel to a struggling dancer, and very kind with her praise and encouragement to another, both critical and supportive. She could pick out the dancers with leading ballerina potential, and those who were strong members of the corps. There was no question that she was in charge, but she knew when to give way, such as when one dancer was fired because he could not be available for a particular tour. The rest of the Company objected, and she hired him back.

Celia’s dancers saw what she was accomplishing in creating the National Ballet of Canada, and they recognized the gifts she gave to each of them personally. Bob Ito describes it as follows: “Looking back, I’m so grateful to Celia Franca for the opportunity she gave me, with her support and encouragement. She launched me into a career that I have enjoyed and prospered in. The many disciplines I learned in the ballet company have stayed with me. Thanks, Miss Franca.”

—Jocelyn Terell

CELIA FRANCA LATER YEARS

THERE IS ONE WORD THAT penetrates the extraordinary fabric of myth and fact that clothes the memory of Celia Franca: “redoubtable.” This means awe-inspiring, formidable, daunting, impressive, indomitable, fearsome, invincible, doughty, and alarming. By 1971, I was writing about dance just as the National Ballet Company really started coming into its own as a front-rank artistic endeavour in Canada. Its dancers were winning international competitions; its productions were being reviewed by The New York Times. Famous figures in the dance world, like Erik Bruhn and Rudolf Nureyev, were keen to sign on for guest appearances or to direct full-length productions. It was a golden era, especially for Celia Franca, who had fought for this moment with every ounce of her being.

It was impossible not to admire the struggle and tempestuous spirit that sustained her. She was a classic founding figure who didn’t brook much opposition, who was used to setbacks and picking herself up again, who could defend her turf like a modern-day Boadicea, and who kept the goal of a national troupe worthy of international approbation and support in front of her at all time. As critics and board members alike would always eventually discover, Franca was indomitable and formidable. I once remember talking to a former National Ballet Board Chair, Senator Jack Godfrey. I asked him how he enjoyed his period at the constitutional helm working with the artistic director. He just looked at me with wild eyes. “Enjoy?” he asked me, almost incredulously. “Enjoy? That’s not the word I would use. ‘Survive’ is the word I would use.”

—John Fraser

KAY AMBROSE

KAY AMBROSE HAD WORKED with Celia Franca in England and came to Canada to help her establish her new ballet company. She was vital to the development of the National Ballet of Canada in its early years. Between 1951 and 1961 she designed sets and costumes for thirty productions including Coppelia and Swan Lake.

Originally known as the author of The Ballet Lover’s Companion and The Ballet Lover’s Pocket-book, Ambrose had expertise in classical ballet, as well as in Indian dance, from working for years with the Rom Gopal Dance Company in India. She sewed clothes, designed sets, and almost anything else the dancers needed or wanted. According to Katrina Evanova, during a break in a performance she developed a nosebleed. “A passerby, the illustrious Kay Ambrose, acting as a nursemaid, ordered me to lay down on the concrete floor, and began pinching my nose in the appropriate area. I was grateful to her.” Donald Mahler reiterates, “Celia and the Company really depended on her. She did everything for the dancers.”

Oldyna Dynowska and Kay Ambrose, 1952.

Courtesy: Myrna Aaron Electronic Archives at Dance Collection Danse.

Ambrose always carried with her a sketchbook, including to hockey games and wrestling matches, where she was fascinated by the way people move. She was inspired by the early dancers and choreographers with the growing Company, believing they had the potential to become of international excellence. Speaking of the Company in the Los Angeles Times in 1958, Ambrose recalled, “They have what Canada has, and it jumps out at you the moment the curtain goes up. I think it is vitality.”

—Jocelyn Terell

BETTY OLIPHANT

I CAME TO CANADA FROM ENGLAND in 1951, when I was four years old. Celia Franca, also from England, had arrived in Canada just a few months prior to start the National Ballet of Canada. Franca needed a ballet mistress for the Company and chose Betty Oliphant. Miss O., as we called her, was also from England and arrived in Canada with her Canadian husband and two children.

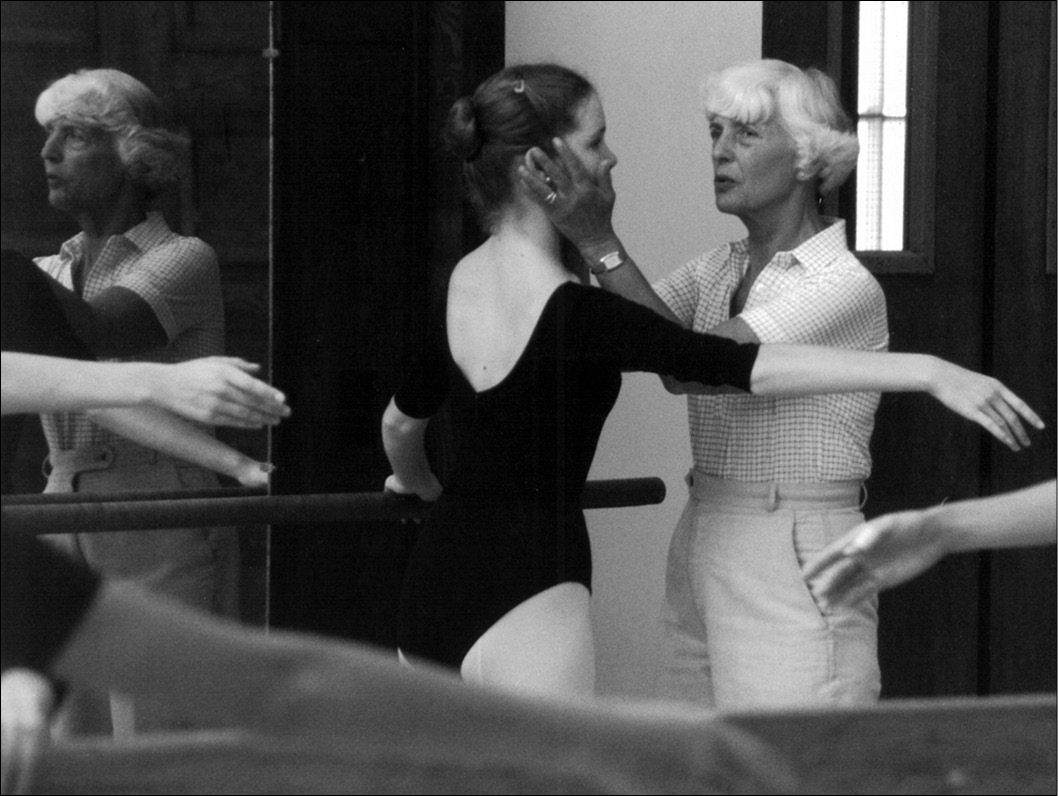

Betty Oliphant, 1980.

Courtesy: National Ballet Archives.

Betty Oliphant, 1980.

Courtesy: National Ballet Archives.

When I was six years old my mother, who had danced ballet in England, decided that Miss O. was the best teacher in Toronto and that I should study dance with her. It also helped that we lived in Willowdale and Miss O. had a Saturday class in the North York Community Centre nearby. Truth be told, I didn’t much like giving up my playtime on Saturdays, but I continued anyway. After a year, Miss O. suggested that I take classes in her “real” studio at 444 Sherbourne Street in downtown Toronto. That’s wheret the like-minded students were, she told me. The studio, which was actually on the main floor of her house, had real dancer barres, not chairs, plus mirrors and a piano accompanist named Mrs. Mahew, and of course, Butterscotch, the cat, who weaved between our feet as we practiced our steps.

It is at Miss O.’s studio that I first met and studied with Nadia Potts, Veronica Tennant, Linda Fletcher, Vicki Bertram, Michele Starbuck, and Barbara Malinowski. But for Michele, all of us went on to join the National Ballet Company. Miss O.’s excellent assistants, especially Nancy Schwenker, also helped us immensely on our journey to become dancers. By this time Miss O. was a single mother of daughters, one of whom also took ballet lessons. The house was like my second home.

Miss O. introduced us to the National Ballet by taking all of us to the Royal Alexandra Theatre. We would watch from the second balcony for fifty cents. Each time the lights would dim, the music would start, and the curtain would rise on this magical land of beautiful dancers and costumes. After one particular performance of Swan Lake, Miss O. took us backstage to meet Lois Smith and David Adams. There Lois was, in her white tutu so wide it grazed both sides of the hallway. Right then I knew that she was all I wanted to be—the Swan Queen. And so it was that I danced Swan Lake as my first full-length ballet with the Company in 1972.

Classes continued, but now we were die-hard fans of the Company’s dancers. The costumes for the ballets were stored in a room in the basement of Miss O.’s studio where we all got changed for class. We would, of course, try them on, imagining what it might be like to dance in them on stage. Naughty, maybe, but so much fun. In those days, Miss O. would call Barbara, Michele, and I “the Three Brats.” Depending on who was in favour at the time she would rearrange our names. The first coup came when Barbara was chosen to dance Clara in The Nutcracker. What an amazing experience for her, though, in the end, Barbara’s career was short-lived. When we were around ten years of age, Miss O. began to let us take company class at a small, mouse-infested studio on Pape Avenue. Mice or not, we were just happy to be dancing near the people we wanted to be.

When the Company moved to St. Lawrence Hall on King Street, we started doing six-week summer school programmes. As young dancers we could watch the company class take place on the stage in the grand old studio. If it rained, dancers would have to dance around pails strategically placed on the floor to catch the drips from the old ceiling. Watching the classes, we really got to know the dancers, and of course we were able to bother them for their autographs. Those summer schools were a unique time. We would only get two weeks off for summer holidays. Miss O. was still ballet mistress for the Company but was also still running her own school. She kept us under her wing, just as though we were her own children.

Then in 1959, Miss O., with Celia Franca, officially began the National Ballet School, now called Canada’s National Ballet School. Miss O. spoke to my parents to invite me to be one of the first students at the School, however, my parents could not afford the eight hundred dollars for tuition. Miss O. set out to find me a scholarship and she found it with the Ladies Auxillary. I was awarded a six-hundred-dollar grant each year for the five years that I was at the School. We started out in a small classroom at 410 Jarvis Street and the Quaker Church on Maitland was the main dance studio. Once the School started, we younger dancers didn’t see as much of the Company as we had before.

In 1960, the Company was presenting Aurora’s Wedding. Our little group—there were six of us and we were all about thirteen—danced a number near the beginning of the ballet. These were our first steps on the Royal Alexandra stage. We had arrived. Maybe just as little bunny fairies, but on the stage nonetheless. From there on, Miss O. took on the role of school principal, full-time. Though Miss O. is something of a polarizing figure for many, she taught me my first plié and watched as I danced my first performance. I became a ballerina much in part because of the opportunities and time Miss O gave to me. For this reason, my feelings towards her have always been of love and gratitude. She was like a second mother to me.

I thank her for everything she did. Miss O. was a pioneer of dance in this country. And with the help of Celia Franca they forged the Ballet School and Company we have today. I was lucky to have a love of dance from a young age and that it turned into a long career.

—Vanessa Harwood

ANTONY TUDOR

ANTONY TUDOR HAD BOTH an indirect and a direct influence on the founding and development of the National Ballet of Canada. Born in London in 1908, and considered a titan of twentieth century ballet, he began his training at age nineteen, in 1927, with Marie Rambert of the Ballet Rambert. He choreographed his first ballet for this company, Cross-Gartered, in 1931 at age twenty-three, drawing on Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. In 1938 he founded his own company, the London Ballet, and in 1939, at age thirty-one, left London for the United States, where he was a dancer and choreographer for the American Ballet Theatre in New York for a decade. He was part of the ballet and ballet school of the Metropolitan Opera, and taught at the Juilliard School of Music.

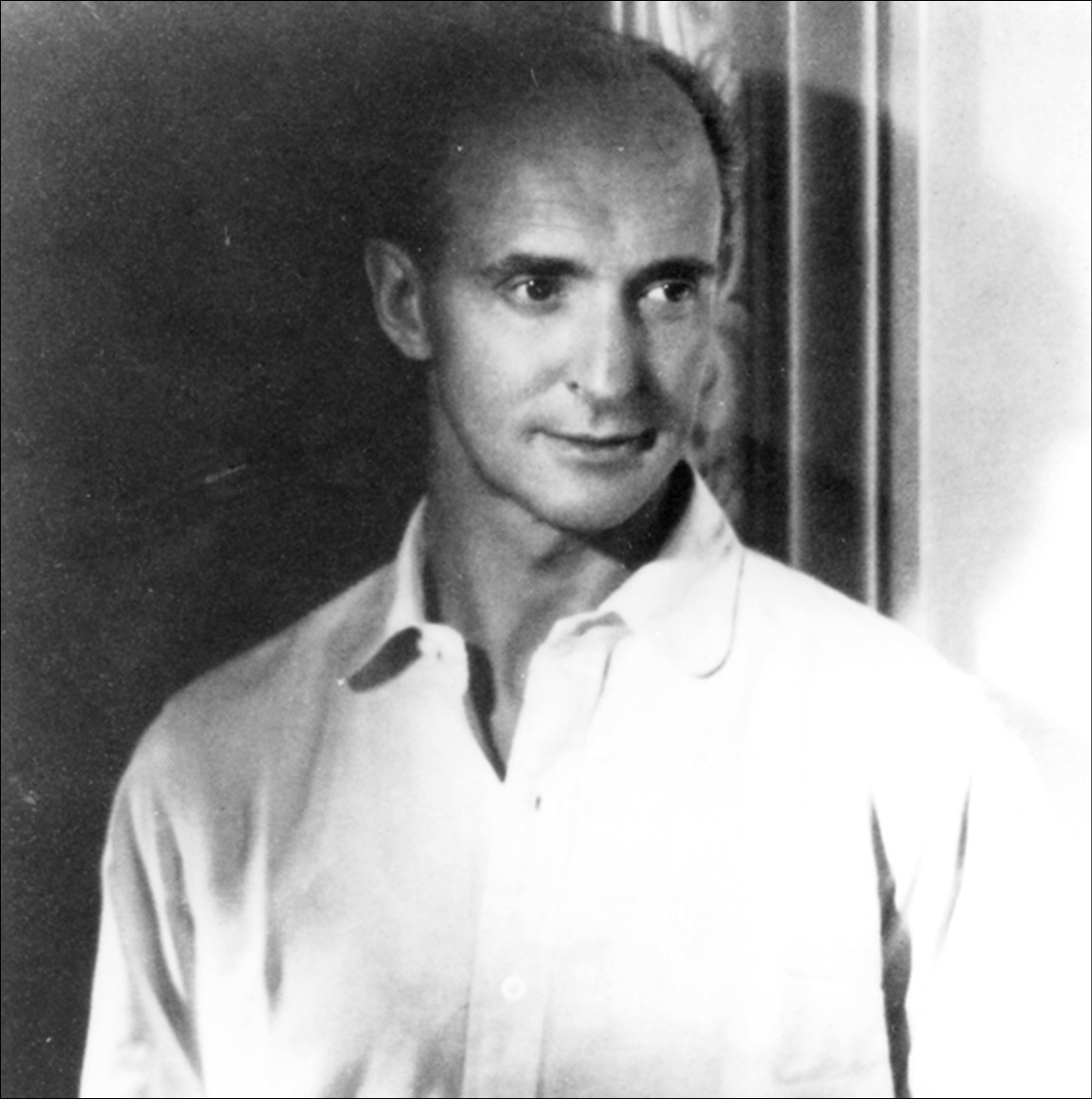

Anthony Tudor. Courtesy: National Ballet Archives

Tudor is known primarily for his dramatic psychological productions and choreography, such as the tragic Dark Elegies in 1937 and comic Gala Performance in 1938. He created Lilac Garden in 1936 on the themes of grief, jealousy, rejection, and frustration. He always made clever use of the corps de ballet.

Tudor was one of a number of mid-twentieth century choreographers to create a more dramatic and psychological form of ballet (Cranko and Forsythe in Germany, and Bejart and Petit in France also contributed to this form). In doing this, they also drew on and developed the skills of new types of dancers. One of the significant persons influenced by Tudor’s work was the New York City Ballet’s George Balanchine.

Because Tudor and Franca had worked together at the Ballet Rambert, he gave his ballets to the National Ballet of Canada. This gift was a big boost to the Company in the early years. Lilian Jarvis notes that her “most enjoyable later roles were also in keeping with my lyrical and character preference,” such as dancing the part of the Sister in Lilac Garden. Yves Cousineau states that working with Tudor moved him forward in his dancing. “The pleasure of getting under the skin of a personage. To advance, but also to play. Thank you Antony Tudor…. Tudor’s musicality was remarkable. For years we were able to have his ballet Dark Elegies (music by Gustav Mahler), a gem rarely seen today, made for a small stage.”

—Jocelyn Terell

LOIS SMITH

LOIS SMITH WAS BORN IN HUMBLE SURROUNDINGS to working-class parents at the end of a trail called Pandora Street in Burnaby, British Columbia. The attending midwife pronounced that newborn Lois would one day be famous because “she was born with a veil covering her”—a poetic euphemism for a remnant of the amniotic sac. Lois’s English immigrant father was a shoemaker. He encouraged his daughter’s love of sports, especially gymnastics. When she was six, a family friend offered to pay for ballet classes but her proud parents declined. Four years later her older brother Bill contributed enough from his job for Lois to attend a weekly class at the British Columbia School of Ballet. He lost his job six months later and the ballet classes abruptly ended. After grade ten, Smith enrolled in a commercial school. She saved enough from summer jobs to take daily ballet class at the Rosemary Deveson School of Dance and within seven months had acquired enough technical skill to audition for and be accepted into Theatre Under the Stars.

By the summer of 1949, when nineteen-year-old Lois Smith met David Adams, she had already acquired considerable stage experience. She had become a featured artist at Theatre Under the Stars, and been hired for a lengthy North American tour of Oklahoma including Smith’s first performance in Toronto. Winnipeg-born Adams, in his mid-teens, had joined Gweneth Lloyd’s fledging Winnipeg Ballet. In 1946, he went to London to perform and met Celia Franca. In 1948, he returned to Canada and re-joined the Winnipeg Ballet, where he continued to dance and choreograph. In 1949, he took a contract as leading man with Theatre Under the Stars. Lois and David married within the year and they had a daughter in April 1951.

Lois Smith and David Adams in Encore! Encore!, 1986. Photo: Marilyn Westlake.

Courtesy: Lois Smith Electronic Archive at Dance Collection Danse.

At this time Celia Franca was well advanced with her plans for a national ballet company. She dearly wanted twenty-two-year-old Canadian dancer David Adams. Lois Smith had an impressive background in musical theatre, but limited experience in classical ballet. Adams issued an ultimatum: hire his wife too, or Franca could not have him. So Franca agreed to hire Lois, sight unseen. She had no cause to regret it. There had been other gifted Canadian female dancers before her and there were others among the ranks of the National Ballet in its formative years, but exceptional talent and the circumstances of her professional environment conspired to propel Lois Smith to become Canada’s first home-grown prima ballerina.

Smith—elegant, graceful, and dramatically compelling—won the hearts of audiences as the young National Ballet criss-crossed North America. Meanwhile the CBC’s new television service, launched in 1952, created new opportunities for disseminating the arts across the country. Franca, who already had experience adapting ballet for the small screen in London, worked with producer Norman Campbell to broadcast the National Ballet to a mass audience. In the process, the Ballet’s leading dancers, particularly Lois Smith, acquired a level of recognition unimaginable to earlier generations. This was amplified by her star partnership with her husband, David Adams. Adams’ virility and attentive partnering served to highlight Smith’s delicate femininity. Smith’s natural poise and authority—often the cool counter to Adams’ pyrotechnical heat—soon won her a devoted public following. While he partnered many ballerinas, it was the magical quality he and Smith projected on stage—their physical and emotional compatibility—that made them true celebrities.

—Michael Crabb

DAVID ADAMS

DAVID ADAMS’ DANCE CAREER BEGAN in 1938, at the age of ten, when he auditioned for and became one of the few male members of the Winnipeg Ballet Club. Within a short time, he would become a charter member of the Winnipeg Ballet Company. David’s first stage appearances, only one year later, were part of a Cavalcade of Welcome for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth during their visit to Winnipeg in 1939. In 1945, at the age of seventeen, David went on tour with the company—the first tour of Canada by a Canadian ballet company. It was not long before he began to dance some lead roles, following in the footsteps of previous soloist, Paddy Stone, who departed from the company in 1946.

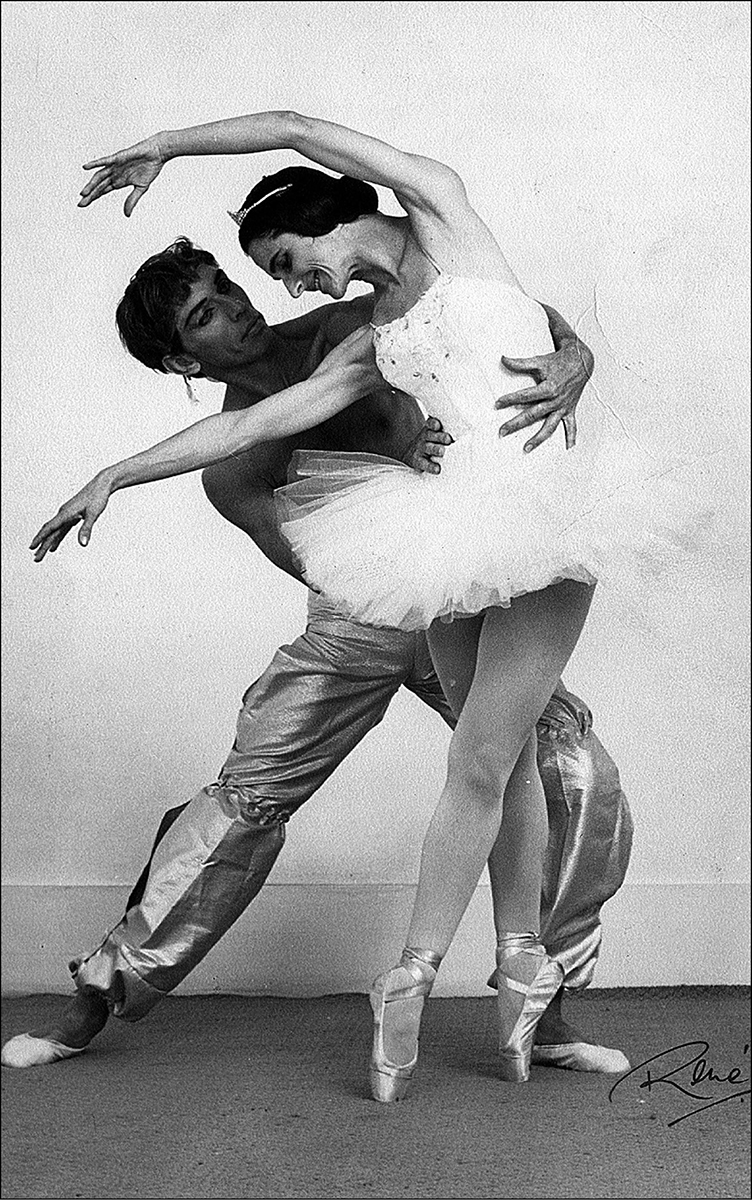

David Adams and Lois Smith.

Courtesy: Lois Smith Electronic Archives at Dance Collection Danse.

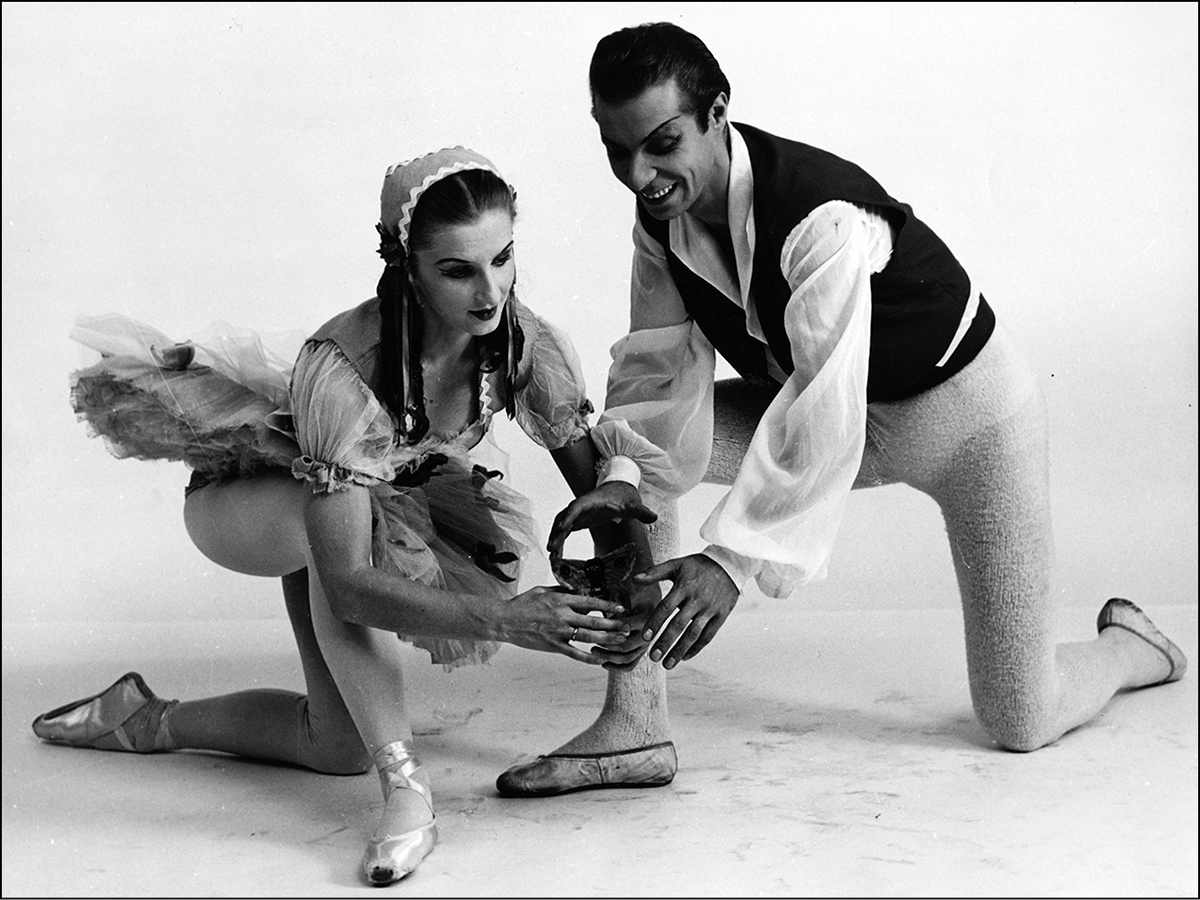

Lois Smith and David Adams in The Nutcracker, 1951. Photo: Ballard and Jarrett.

Courtesy: National Ballet Archives.

In April of that year, David received a scholarship to study at the Sadler’s Wells School in London, England. On September 26, 1946, David departed from Canada, setting sail for England on The Aquitania. He was to stay at least one year, studying the art of dance, with the possibility of accepting performance opportunities. At ages eighteen and nineteen, David worked with many influential choreographers and danced in several productions with both the Sadler’s Wells Company and the Metropolitan Ballet. Some highlights were dancing with the Russian ballerina Svetllana Beriosova and with the English dancer, Celia Franca, with whom David would later reconnect during the formation of the National Ballet of Canada.

David returned to Canada in October of 1948, and soon began staging many of the classics for the Winnipeg Ballet Company, sharing the expertise he had gained while he was in England. In 1949, at the age of twenty, David created Ballet Composite, his first piece of choreography. This new work received good reviews and became part of the company’s repertoire. It caught the eye of Mara McBirney, a British teacher living in Vancouver, who offered David a job to teach at her studio. He accepted and signed a contract to perform with Theatre Under the Stars in the upcoming summer season.

It was during his time in Vancouver, dancing “under the stars,” that he met the first love of his life, Lois Smith. They danced together in Song of Norway, receiving several standing ovations, with an extended tour in Victoria. David and Lois soon became technically brilliant and popular ballet stars as premier principal dancers with the National Ballet of Canada. Throughout the 1950s, the Company toured across Canada, the U.S., and Mexico City. In May of 1961, David decided to seek new opportunities abroad; he returned to England at the age of thirty-three, without Lois. He joined London’s Festival Ballet, eventually dancing with that company full-time in 1964. He danced many lead roles and toured several places in Europe, Israel, and South America.

At the invitation of Kenneth MacMillan, David joined the Royal Ballet in 1971 to partner Lynn Seymour in the ballet Anastasia. He also danced several character roles, toured with the company all over the world, taught pas de deux classes, and directed a sub-company, Ballet for All. In 1977, at age forty-seven, he returned to Canada to take the position of ballet master with the Alberta Ballet Company.

David Adams’ amazing contributions to dance in Canada are best described in the eloquent words of Gunnar Blodgett. This tribute to David’s legacy was incorporated into the Citation, read by Adrienne Clarkson, former Governor General of Canada, at his investiture ceremony when David was awarded the Officer of the Order of Canada. The citations reads as follows:

“One of our first stars of ballet, David Adams, has had an enormous influence on Canadian dance. A founding member of the National Ballet of Canada, he helped to shape the fledgling company’s style. Technical brilliance and superb artistry became its hallmark and, throughout his tenure as principal dancer, choreographer, and ballet master, he dazzled audiences with magnificent productions. Former technical director, ballet master, teacher and choreographer of the Edmonton Festival Ballet and Grant McEwan College, he has shared his immense talent with generations of performers and his impact will resonate for years to come.”

—Meredith Adams

LAWRENCE ADAMS, THE DANCER

ALTHOUGH HE DANCED IN THE SHADOW of his famous brother, David Adams, Lawrence Adams was an excellent dancer and a non-conformist at heart. In 1955, he joined the National Ballet of Canada, dancing mainly in the corps de ballet. He also danced the part of Friend in Tudor’s Lilac Garden as my partner. He left the National Ballet in 1961 to join Les grands ballets de Montreal, then in 1962 went to New York’s Joffrey Ballet, returning to the National Ballet of Canada in 1963. Here he danced as a soloist and principal dancer, known for his athleticism, vitality, and exuberance. He was chosen by Grant Strate to be a peasant in Strate’s The Fisherman and His Soul, based on Oscar Wilde’s fairy tale. He was also one of the dapper young men in Tudor’s Offenbach in the Underworld. He had beautiful, expressive feet and a natural dancer’s body. Upon his return to the National Ballet, he created two memorable roles: Mercutio in Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet and later the Captain in Cranko’s Pineapple Poll. In Romeo and Juliet, Lawrence was spectacular, full of mischief, hilarity, and bantering friendship to Earl Kraul’s Romeo. I had joined the National Ballet Company for the Carter-Barron engagement in Washington, DC, and was in the audience where I witnessed a truly wonderful evening when Lawrence’s performance as Mercutio brought down the house. Much later he danced the Captain in Pineapple Poll to rave reviews. Lilian Jarvis, who knew Pineapple Poll well, wrote: “I’d never tire of Lawrence’s musicality, precision, and immersion as the Captain in Poll.”

Miss Franca had hoped that Lawrence would form a partnership with Martine van Hamel, as she had cast them together in the Snow Scene of Nutcracker as Prince and Snow Queen, as well as in La Bayedere Act II. Unfortunately, Martine went on to the American Ballet Theatre and Lawrence left to found Dance Collection Danse (DCD) and “15” Laboratorium. He had already proven that he was a formidable dancer, but he found the ballet world too restricting.

—Jocelyn Terell

LAWRENCE ADAMS, THE VISIONARY

SUMMER 1973: In “New Homes for Dance in Toronto,” an article for Performing Arts in Canada, I wrote, “The new group of four dancers called ‘15’ are liberated from many conventional dance hang-ups. Their first work was in a sense the process of making the George Street place, which they have longingly done by themselves. Their forty-one-seat theatre is a little gem, vibrating with promises of future experiments and discoveries.”

I described an untitled dance by Miriam. “Lawrence Adams and Diane Drum lie asleep in pyjamas in the centre of the arena. Sometimes Lawrence gets up and does something like the Twist. A bad dream of a ballerina (Miriam Adams) in warm-up attire clumps in. She is swathed in plastic and her dancing is hard as nails. Time passes. She sheds her clothes layer by layer as she fiercely goes about her work. From time to time, Lawrence jumps up to lift her briefly in balletic flight. Lawrence says some hilarious things about dance and art in connection with what goes on “under the sheets.” It is a crazy vision of a dance, which one would willingly return to.”

Over the next three decades, I returned many times to see Lawrence and Miriam, marvelling at the activity they initiated through the “15” Dance Laboratorium, the Encore! Encore! reconstructions and Dance Collection Danse (DCD).

Lawrence’s brilliant work and unconventional leadership inspired many to remember him in words. Tributes by colleagues and a succinct biography by Paula Citron are collected in DCD Magazine Issue 56 (2003). Articles in the anthology, Renegrade Bodies: Canadian Dance in the 1970s, edited by Allana C. Lindgren and Kaija Pepper (2012) provide further insights and context. Mentored by Lawrence in his last years, Amy Bowring completed Lawrence’s extremely useful Building Your Legacy: An Archiving Handbook for Dance (2004) and distributed hundreds of copies to dancers and students.

“Dance power”—dance legacy—yes!

—Selma Odom

ANGELA LEIGH

ANGELA LEIGH WAS ENDURINGLY CREATIVE as a ballerina, artist, and teacher. As a teacher in the dance program at York University, she was a revelation—exotic, stylish, outspoken, and idiosyncratic. Angela had recently studied yoga in India and started each class with yoga practice, highly unorthodox in the early 1970s. She had embraced the free-spiritedness of the late sixties and early seventies, dressed in flowing clothes, and often with a scarf bound around her blonde curls. Angela had a keen sense of humour, and a nonjudgmental approach that coaxed out students’ latent aspirations and talents. She shared her passion for motion, imparting lyricism and deep physicality in her ballet classes.

Born in 1927 in Uganda, Angela studied ballet in London with the Royal Ballet, where she worked with John Cranko. After World War II, she and her family immigrated to Canada. She started teaching in Barrie and Orillia but soon gravitated to Toronto. Celia Franca hired Leigh as a principal dancer and charter member of the National Ballet Canada. Angela’s friend, Joysanne Sidimus, recalls that she was “very beautiful, long, lean, fine-boned with long, elegant feet” and that Franca recognized her potential to impart a sense of glamorous femininity to the fledgling National Ballet, at that time largely populated by very young dancers. Angela danced most of the lead classical and contemporary roles, including the Black Swan in Swan Lake to Jocelyn Terell’s White Swan Queen, partnered by Earl Kraul. She was often partnered by Joey Harris, known professionally as Ivan Demidoff. Angela could make difficult choreography work for her, recalls Sidimus, as she was a sophisticated mover. For example, Grant State’s Triptych, set to the Mozart clarinet concerto was a challenging choreography that she somehow managed to do well and with aplomb.

Angela’s second marriage to Canadian filmmaker and writer, Paul Almond, connected her with many luminaries in film and television. In 1963, she landed a lead role in the film, The Other Man. She constantly re-invented herself in creative ways. She would go on to teach and coach at Canada’s National Ballet School and the National Ballet of Canada. She became an assistant professor of York University and taught at George Brown College. She delved into choreography, creating work with the National Ballet School, Dancemakers, the Canadian Opera Company, and Ontario Ballet Theatre. She was also a talented designer who had a penchant for renovating and decorating houses, and worked on residential and commercial properties. As a fabric artist, she created unique silk garments, paintings, and décor. When she moved to Victoria, she became an advisor to Ballet Victoria, the company she had helped found. Angela Leigh is vividly remembered for the bold and creative elan with which she danced through life.

—Carol Anderson

TERESA MANN

MY MOTHER, TERESA MANN, WAS AN ARTIST. If I could describe her in two phrases, I would say she loved to dance, and she loved God. These two descriptions summed up her whole life, her entire self, her reason for existing.

Her mother, Rosaura de Obarrio was Panamanian and her father, Henry Mann, who came to Panama with the Royal Bank of Canada, was Canadian. Teresa was born in Panama but at age two the family moved to Caracas, Venezuela, where she began her dance lessons. A few years later, the family moved again, to Lima, Peru, where they lived for several years and she continued her passion for dance. After high school she moved back to Panama where she became one of the founding students of the National Ballet School of Panama. By that point all she wanted to be was a ballet dancer. Eventually she moved to New York City to pursue her dance career. There she saw the National Ballet of Canada perform for the first time. She fell in love with the Company and enrolled in a National Ballet of Canada summer course in Toronto. Celia Franca offered Theresa a contract to join the dance company.

Earl Kraul and Teresa Mann. Courtesy: Private collection.

My mother danced with the National Ballet for five years, from 1956 to 1961. She told stories about their tours and the hours spent on buses. She said there were several buses, one for principals and soloists, another for the corps members and one for the orchestra. She made lifelong friends like Shirley Kash (Tetreau), a dancer and later a teacher at the National Ballet School, and Mary McDonald, their pianist. My mother had a deep admiration for her colleagues of those early years: Brian Macdonald and David Scott, Joanne Nisbet, David Adams, Lawrence Adams, Lorna Geddes, Victoria Bertram, Mary Jago, Jocelyn Terell, Beverly Banfield, Jeannette Cassels, Collen Kenney, Angela Leigh, Brian Madonald, Ian Robertson, and Grant Strate. She and Earl Kraul, who was principal dancer in the early years, would become friends and she convinced him to come be a guest artist with the National Ballet of Panama. They danced together and had great respect for one another. Some other dancers from those early years in the Company would also end up as my teachers, such as Lilian Jarvis and Glenn Gilmour. My mother was also very good friends with Patricia Neary who became a principal dancer with New York City Ballet and worked with George Balanchine, the famous choreographer. My mother held great admiration for Celia Franca. She spoke to me about her strict discipline and work ethic. I would often hear about her and Betty Oliphant, cofounder of the National Ballet School.

Teresa Mann danced until she was fifty. For her last performance she danced The Dying Swan in her Teatro Municipal of Lima, the same theatre where she danced for the first time at the age of five. Once she knew she wanted to retire, she danced five more years, “to be totally sure,” she told me. I always admired that strength, determination, and commitment in her. She was a strong woman.

—Myriam Mann

EARL KRAUL

EARL KRAUL WAS A TAPPER BY NINE, but in his teens was inspired to pursue ballet by Eugene Loring’s Billy the Kid. Two years after joining the National, he was promoted to soloist where he drew critical attention. In July 1951, the Toronto drama critic, Herbert Whittaker picked out “the promising Earl Kraul.” In his review of their launch that November, Whittaker described Études, the pas de quatre featuring Earl, as “the most encouraging, refreshing item on the program, while praising his “vitality and attack” in the Polovtsian Dances. Critics around the continent agreed. Accounts of Earl as a dancer on the rise included “dazzling exhibition—inordinately powerful—soaring with grace belying his strength.” Versatility, too, was apparent early on. His work in the western-themed Ballad was described as “violent and passionate,” his performance in Strate’s The Fisherman and His Soul praised as “dramatic, fantastic, and full of pathos.”

Audiences responded to Earl. They felt his momentum and were moved by his emotional depth. He had, as well, the striking good looks of a hero from a Norse myth. Vancouver’s Robert Sunter wrote that Earl Kraul’s “empathy has made him Canada’s premier dancer,” his work was “full of grace and fluid, muscular vitality.” He was relentless in the face of technical challenges, yet moved with ease and a velvety tread.

We admired him above all, however, for his creativity in roles and for the personality he brought to the stage. From his boyish charm as Franz in Coppelia to his anguish as Orestes in Strate’s House of Atreus, Earl was a dancer who put story first. He was enigmatic and soulful in Solitude and brought tragic desperation to Les Sylphides. Most of all we were stirred by his conviction as the star-crossed lover in John Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet. As Romeo, Earl created a signature role for himself and helped establish a new phase in the National Ballet’s history. He was the home-grown Canadian who so movingly embodied the famous lover and, with Veronica Tennant, personified the company’s coming of age.

In those heady days of the Romeo and Juliet launch, we watched, enthralled, as Veronica blossomed in his sensitive hands. But it was more than partnering technique on display. He was first and foremost a lover. From the moment, he spied her in the ballroom scene you felt the lightning sear through his being and later, under the balcony, the waves of their passion flooding the stage.

As a fighter he was equally intense. No one who ever saw them clash could forget his struggles with Yves Cousineau’s Tybalt. Yves’ Prince of Cats was a formidable foe and their conflict acquired iconic status. In the production’s first weeks, an extraordinary event electrified the cast and crystallized awareness that this was a new phase in the Company’s identity: Romeo (Kraul) and Tybalt (Cousineau) were locked in their duel when Romeo’s rapier snapped off in his hand. He defended himself with the hilt and stub of his sword as the music reached its climax, when suddenly Benvolio (Glenn Gilmour) slung his sword toward Romeo, the blade whistling through the air, spinning end over end. On the final, shimmering chord, Romeo grabbed the sword out of the air with his free hand, and dealt Tybalt the final, fatal blow.

Stunts like this had never been seen in the National Ballet before. The ovation lasted longer that night than anyone could remember and the Company was transformed. Those present still marvel at Earl’s self-possession in the heat of passion, at his nerve, dexterity, and flair. In that one moment, he brought the artistry and commitment of the entire Company into focus. It was no longer just about dance. We were now in the business of theatre. Nureyev’s 1972 Sleeping Beauty was arguably made possible by the ongoing Romeo and Juliet effect, and especially by Earl’s contributions at the heart of the action.

—Timothy Spain,

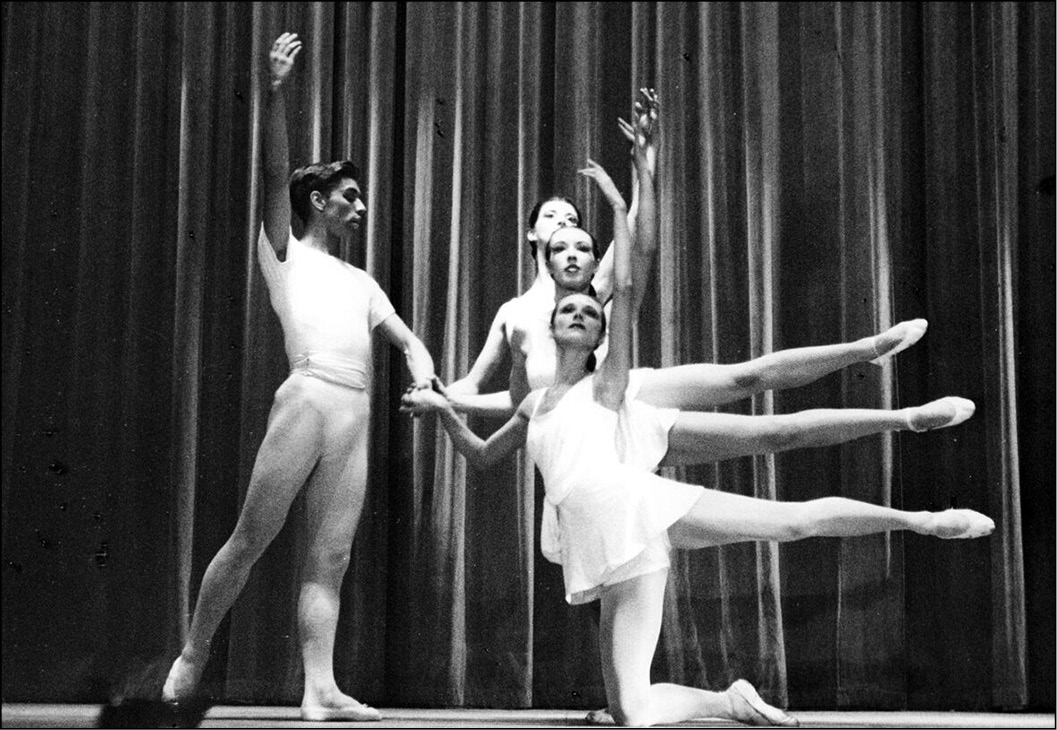

Earl Kraul, Oldyna Dynowska, Katherine Stewart, Natalia Butko, Étude.

Courtesy: Lois Smith Electronic Archives at Dance Collection Danse.

Earl Kraul, Natalia Butko, Katherine Stewart,and Oldyna Dynowska, Étude.

Courtesy: National Ballet Archives.

EARL KRAUL—MY FIRST ROMEO

HOW BLESSED WE WERE TO HAVE the pre-eminent Earl Kraul teach us pas de deux in those early (and for me final) years at the National Ballet School. We’d watched his dynamic dancing and his superb partnering with Lois, Lilian, Jocelyn—indeed most of the women dancing with the Company—with awe. He had the gift of charisma, a magnetic stage presence, and was a premier danseur of technical accomplishment, dramatic finesse, and irrepressible generosity. Earl, a consummate partner, was an incomparably gifted teacher and I adored those classes where he would coach us novices to understand how the synchronization of our musicality, breaths and pliés, our take-offs and mutually protected landings could give reality, and thus illusion, to the choreography. He inspired the men—Sam Moses, David Earle, Andrew Oxenham, John Klampter, and Tim Spain, among others—by unmatchable example and clarity of explanation. And happy were the times when he would demonstrate with me!

Lucky, lucky me to be chosen to dance Les Sylphides with Earl, Mr. Blue Eyes, in my graduation year. I had a huge crush on him already! He was strong. He was funny. He was fun. I mooned for months over the romance, poetry, and bliss of that experience. And then—after missing a year due to a back injury—I entered the Company in 1964 at eighteen and was cast by the very brave Miss Franca to dance Juliet. While Miss Franca took an enormous chance on me, she knew what she was doing when she put me in Earl’s arms—and he swept me off my feet. If Juliet set the course of my dramatic dancing career, Earl Kraul nurtured the takeoff. Without him I could have neither braved the tightrope path, nor succeeded. For what is Juliet without her Romeo?

Veronica Tennant and Earl Kraul after a performance of Romeo and Juliet, 1964.

Courtesy: Private collection.

So many touching memories flood back from the first performance and every single one after. From that first sight of each other at the ball, those mesmerizing blue eyes made my heart stop. The dreamy madrigals, first touch of palm to palm, the sheer romance of the balcony scene, our first kiss, the bliss of the wedding, the pain of our parting, and the grief of our tragic ending.

I remember Windsor, Ontario, where we toured regularly. Earl took me aside before a performance. With an uncharacteristic seriousness on his face, he said, “I want to have a word with you,” and then presented me with an exquisite Georgian garnet pendant for my nineteenth birthday. As a friend, Earl defined generosity and tenderness. And it was my honour to dance with him.

—Veronica Tennant

GRANT STRATE: HIS EARLY LIFE

IN 1950-51, CELIA FRANCA EMBARKED on a nationwide tour to audition dancers for the founding of the National Ballet of Canada. In Edmonton, she first encountered Grant Strate, then a young, untried, primarily modern dancer. With her uncanny ability to intuitively sense potential, she learned he was a graduate lawyer who, after a year of practicing law, decided he’d rather be a dancer. Her instinct led her to someone who evolved over the years from dancer to choreographer-in-residence, and an overall critical voice in the development of the Company’s repertoire and policies. During his time with the National Ballet, Strate created twenty works, many involving Canadian composers and designers. A complex and talented man, Strate’s challenging, inquiring mind always served as a catalyst for action. While Franca stayed with the Company, she encouraged him to travel, seeking both influences and choreographers advantageous to the young company. His most important achievement was bringing John Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet to the Company, which coincided with a move from the Royal Alexandra Theatre to the then-new four-thousand-seat O’Keefe Centre (now the Sony Centre). It was a tremendous shift for the Company and one that catapulted them into international recognition.

Grante Strate and Lilian Jarvis in Afternoon of a Faun, early 1950s. Photo: Ken Bell.

Courtesy: National Ballet Archives.

Strate’s choreographic process was always interesting, if somewhat improvisatory, perhaps due to his lack of formal balletic training. Though he was rigorously immersed in ballet training once he joined the Company, modern-based movement seemed of great interest to him as a choreographer. At the time, he was planning to choreograph House of Atreus, one of three ballets on the Electra theme. The first, a chamber work, had met with great success the previous year when he was a guest at Julliard in New York. This time he was planning a much bigger work—an all-Canadian production with a commissioned score by celebrated composer, Harry Somers, and set and costume design by the famous artist, Harold Town. He had to pull the show together on a short timeline, but it worked. Similarly, when he choreographed Pulcinella to a Stravinsky score, there were so many bourrees on pointe that all three dancers sharing the role of Pimpinella had to change shoes halfway through the ballet to accommodate this request.

Strate had an action-oriented sense of justice. When he choreographed Electra with an electronic score by Henri Pousseur in Glenn Gould’s Stratford Summer Music series, he invited Arthur Mitchell, Balanchine’s brilliant black principal dancer to portray Orestes to my Electra. This came at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, when television stations in the Southern states refused to show Agon, where Arthur did a pas de deux with Diana Adams, a white principal dancer. Arthur and I were thrilled to be working together again and both the festival and the Canadian audiences didn’t blink an eye.

When visiting artists came to Toronto, his home was the place to go for gatherings. Lynn Seymour, Erik Bruhn, John Cranko, Marcia Haydee, Ray Barra, and many others were welcomed. With his enquiring lawyer’s mind, he would probe these great artists to speak of their ideas and creative processes. He was truly a national treasure: unique, iconoclastic, and yet coupled with profound humanity and generosity of spirit rare in the world.

—Joysanne Sidimus

GRANT STRATE: HIS LATER LIFE

GRANT STRATE ALWAYS TOOK a panoramic view of the dance world. So, when he stepped down from the artistic staff of the National Ballet of Canada in 1971 and immediately stepped up to the role of founding director for York University’s dance department, it was a means to see farther, in more directions, and with greater objectivity. His mandate at York was to educate rather than just train dancers and creators. He built a superlative faculty of artists working within widely varying practices and hosted greats of the dance world as special guest teachers. He sent his students downtown to see Toronto’s professional dancers on stage and those dancers came to York to see performances by the companies of Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, Mel Wong, and other choreographers from New Your City. Strate wanted to fuel ambitious creativity. As the first graduates left York, dance activity in Toronto suddenly expanded in a multitude of radical new directions: artist-run spaces; durational events; work driven by concept, text and technology; work informed by the politics of race, feminism, sexual orientation and the left.

I remember very clearly the meetings held in his living room for the group of fledgling dancers who would become Dancemakers. He assured us that the work itself would teach us how to become professional, to become the dancers we aspired to be. And I will never forget a rehearsal he directed for Dancemakers in 1974, when we were working on a wonderful piece by Norman Morrice, then Artistic Director of England’s Ballet Rambert, and a guest teacher at York. The dance featured Carol Anderson and David Langer. At the end of the rehearsal he shared an abundance of pertinent insights, especially regarding crucial elements of choreography for Carol and David. As he concluded these notes, he paused for a moment, not quite knowing how to work his next thought. Then, he looked at me and said, “And you Peggy, we’re going for an Academy Award.” His candour could always be counted on.

Grant was a keenly intelligent, openhearted man. He was often described as a “statesman of dance.” His life partners, Earl Kraul and later, Wen Wai Wang, were each magnificent companions during his personal and artistic journeys. Grant Strate was a towering presence in Canadian dance. His efforts, influence, and contributions were profound and crucial, and his legacy will continue to move our art form forward for generations to come.

—Peggy Baker

BRIAN MACDONALD

GROWING UP, BRIAN PLAYED THE PIANO and was a child actor for CBC radio, standing on a phonebook to reach the microphone. He was a student at McGill University when he first saw a rehearsal of George Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco with the New York City Ballet. The Company was in Montreal and they had asked if McGill knew of a studio where they could rehearse. Brian was dispatched to tell them yes, and while watching the rehearsal, he knew his life was changed forever. In that moment he decided that ballet and choreography would be what he was going to do. His first teacher, Gerald Crevier, told Brian, “Start with the little children and learn everything from the beginning.” He also trained with Elisabeth Leese.

After graduating from McGill, Brian auditioned for Celia Franca, and was accepted into the Company that became the National Ballet of Canada. The pay was meagre and sometimes Brian would wash the studio floor to earn extra. To make ends meet, there were four or five male dancers sharing an apartment. Among them was Grant Strate. The men would share the cooking—“There was lots of Jell-o.” It was supposed to be good for the joints and it was cheap. Towards the end of the week the funds would run out and the women in the Company would invite the “guys” home for a proper Sunday dinner that their mothers would cook.

Oldyna Dynowska and Brian Macdonald in Ballet Behind Us, 1951.

Photo: Ballard and Jarrett. Courtesy: National Ballet Archives.

Brian loved Celia’s classes as she was a dancer herself and her classes were filled with movement. When Celia organized a choreographic competition within the Company, Brian won the first prize of sixty dollars and was able to buy himself a winter coat. When Olivia Wyatt joined the Company, they became a couple, and during off-season would go the Montreal, where Brian would choreograph for nightclubs or write reviews for the Montreal Herald. At one point, he broke his arm, which meant he could no longer partner, so he turned to a long career as a choreographer and director. The two of them directed and choreographed a wildly successful production called My Fur Lady, a satirical musical, which toured Canada with over four hundred performances. Subsequently, Olivia joined the Royal Winnipeg Ballet as a dancer, while Brian was named the Company’s resident choreographer. After the untimely death of Olivia, Brian went to the Banff School of Fine Arts, to New York, Europe, and Russia on Canada Council grants. He was setting one of his ballets with the Royal Swedish Ballet where he met and married Annette Wiedersheim-Paul, later changed to Annette av Paul. During his career, Brian became Artistic Director of the Royal Swedish Ballet, the Batsheva Ballet in Israel, the Harkness Ballet of New York, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens in Montreal and the Summer Dance Program at the Banff Centre. He was also Associate Director of the Stratford Festival and the National Arts Centre in Ottawa.

Among Brian’s many choreographic works, Rose Latulipe, commissioned for the 1967 Centennial Anniversary of Canada, stands out. It was filmed by the CBC. Add to this, Star Crossed, Brian’s version of Romeo and Juliet; Firebird; as well as Time Out of Mind; Tam Ti Delam; The Shining People of Leonard Cohen; Double Quartet; and Adieu Robert Schumann.

In 1967, Brian was a recipient of the Order of Canada, elevated to a Companion of the Order of Canada. As well, he received the Molson Prize, Walter Carsen Prize, and the Governor General’s Award for Excellence in the Performing Arts. In 2012, the City of Stratford Festival Theatre honoured Brian with a Bronze Star in front of the Avon Theatre.

I was fortunate to inspire, create, and dance many of his ballets and share fifty years of artistic companionship and love with him.

—Annette av Paul

GLENN GILMOUR

GLENN GILMOUR WAS AN INSPIRING DANCER and teacher for generations of dancers in Canada. I had the cherished privilege of working closely with him for over thirty years, first as one of his students at Canada’s National Ballet School, later as his teaching colleague at the same institution, and finally as his boss—although the official label “boss” always felt like a misnomer as I never stopped learning from Glenn.

In 1970, all the National Ballet School students, myself among them, were deeply saddened by the news of Glenn’s retirement from the National Ballet of Canada. We were devoted fans who deeply regretted that we would no long be able to see him dance his many roles of note, most especially his much-admired performances of Benvolio, but our sadness at no longer seeing him onstage was tempered by the exciting news that he was coming to the School to study teaching with Margaret Saul and Betty Oliphant. We were agog that he would be at the School every day. When he arrived, every glimpse of Glenn resulted in our daring one another to strike up a conversation that inevitably ended in a request for an autograph. These requests became so frequent that Betty eventually had to rescue Glenn by putting a freeze on these autograph appeals.

Within a year of coming to the National Ballet School, Betty hired Glenn as a full-time teacher and I was fortunate to be in his first group of students. Glenn did not disappoint. He brought all the passion for dance he had displayed on stage to his teaching in the classroom. As his students, we always felt closely connected to all the reasons we had fallen in love with ballet in the first place. His carefully crafted enchainements and his musical sensitivity turned every exercise into a joyful exploration of the art form and furthered our development as artists. Students were so appreciative of his training that many alumni returned regularly during their holidays to rejoin his classes. But it was not only dancers who recognized his extraordinary musicality. For the next three decades, the School’s musicians jockeyed for the chance to be partnered with him in creative classroom collaboration.

Glenn’s mastery of the language of dance was evident in everything he choreographed. His exam classes were works of art, his lecture demonstrations a pure joy to interpret, and the pieces he created for School’s annual Spring Performances were inspiring for both the dancers and the audience. Perhaps the best known of his ballets was Playing Field, based on William Loring’s Lord of the Flies, which he brought to life in concert with two of his favourite musical partners, Trevor McLain and Robert Swerdlow. Performed four times over fifteen years, Playing Fields proved a seminal experience for each of the all-male casts.

Generous as a teacher, Glenn was equally generous as a teaching colleague. He was someone I was able to turn to in moments of self-doubt. He had a straightforward, no-nonsense view of life. This approach, combined with his sense of humour would have me back on track with a spring in my step and hope in my heart, which is why, when Betty Oliphant offered me the opportunity to succeed her as the National Ballet School’s Artistic Director, Glenn was the first person I turned to for advice. His encouragement to “seize the opportunity,” with his promise to support me every step of the way, meant the world to me. The ways in which Glenn delivered on his promise were an ongoing source of strength for almost twenty years, until his death in 2007.

When Glenn shared his cancer diagnosis with me eighteen months prior to his passing, we agreed on two points. Firstly, that the news of his diagnosis would remain confidential. And secondly, that he would continue teaching for as long as possible. This he did until just two weeks prior to his death. Somehow, even as his physical strength diminished, his love of teaching and his students made him an even more powerful force.

After Glenn’s death, there was a groundswell of momentum to pay tribute to his inspiring contributions to so many, and absolute consensus that the celebration of Glenn’s life had to take place in National Ballet School’s Betty Oliphant Theatre. Although I think Glenn would have been astonished by the need to conduct the tribute twice in a row in order to accommodate everyone wishing to attend, none of us was surprised. On that day, the outpouring of love for Glenn and heartfelt expressions of gratitude for everything he had done through his lifetime were irrefutable evidence of a life more than well-lived.

Thank you, Glenn, from all of us lucky enough to have known you.

—Mavis Staines

DAVID SCOTT AND JOANNE NISBET

HOW WELL I REMEMBER David Scott and Joanne Nisbet’s dedication. The pair moved to Canada from England in 1958, invited by Celia Franca to join her then-fledgling National Ballet of Canada as dancers. They soon found—or Celia Franca soon discovered in them—their mutual calling to head up her ballet staff. Conducting rehearsals, teaching class, delivering post-performance corrections—all of these roles essential to the everyday operations of a ballet company were given the age-old hierarchical titles of Ballet Master and Ballet Mistress and David and Joanne wore these titles well. Joanne transitioned earlier from dancing and took on her position first. Later she would relish the pleasure she felt when reading a press caption that said, David Scott, Ballet Master and his Mistress, Joanne Nisbet.

David Scott and Joanne Nisbet. Courtesy: Private collection

David and Joanne were unstinting in their commitment, indefatigable in carrying out Miss Franca’s vision—they were her officers of excellence. Gentle, compassionate Joanne gave daily classes, much more than just warm-ups, whether in the studio or onstage just before performances. She was always mindful of our injuries and fatigue, our “glass ankles” as she so aptly called them. David was possessed with the devil of detail. He missed nothing and was a craftsman who unrelentingly emphasized the fundamental refining-points of ballet technique in performance. Both David and Joanne coached and rehearsed and taught the Company dancers every step for Celia’s chosen ballets. They served all the visiting choreographers—Antony Tudor, John Cranko, Erik Bruhn—with unreserved commitment and respect.

David once told me that while he didn’t always agree with Celia’s casting choices, he spoke emphatically about his belief in her standards of excellence for the National Ballet as a major company. Together he and Joanne developed a mandate for the implementation of professionalism, uniformity of style, and a signature vocabulary articulating a specialized movement language. Ballet dancers, especially the corps, have a certain “look” which is essential to develop in order to define a company of the first rank. For example, a ballet company is defined and judged by its ability to create single arcs of sweeping movement across the two dozen bodies that populate the corps, as can be found in famous ballets such as Swan Lake, La Bayadère and Les Sylphides. In forging a professional ballet company in those early days, David and Joanne shared one mind with Celia’s insistence on reinforcing group endeavour, a support system of coaching, applied motivation, and a pooled knowledge that worked in tandem with the love of the art.

David Scott recently passed at the age of ninety. For four decades, the National Ballet of Canada was his life and we are deeply indebted to him and to our dear Joanne, who survives him. I can still hear their voices so clearly, though sadly, they are slowly beginning to fade.

—Veronica Tennant

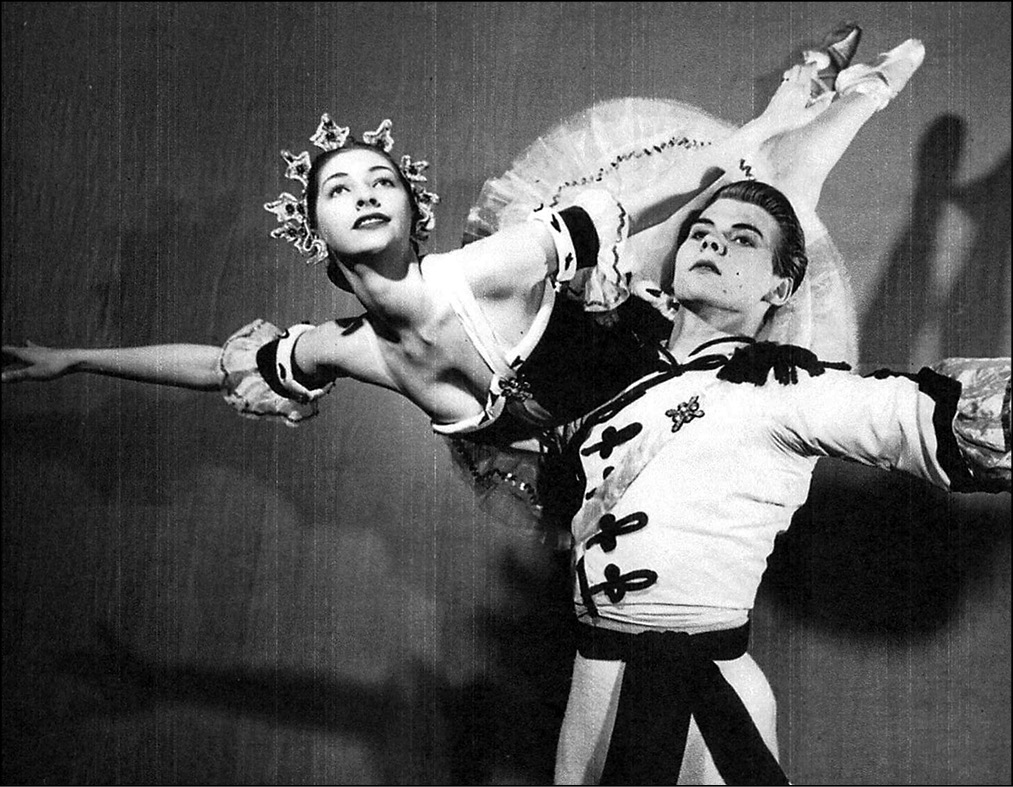

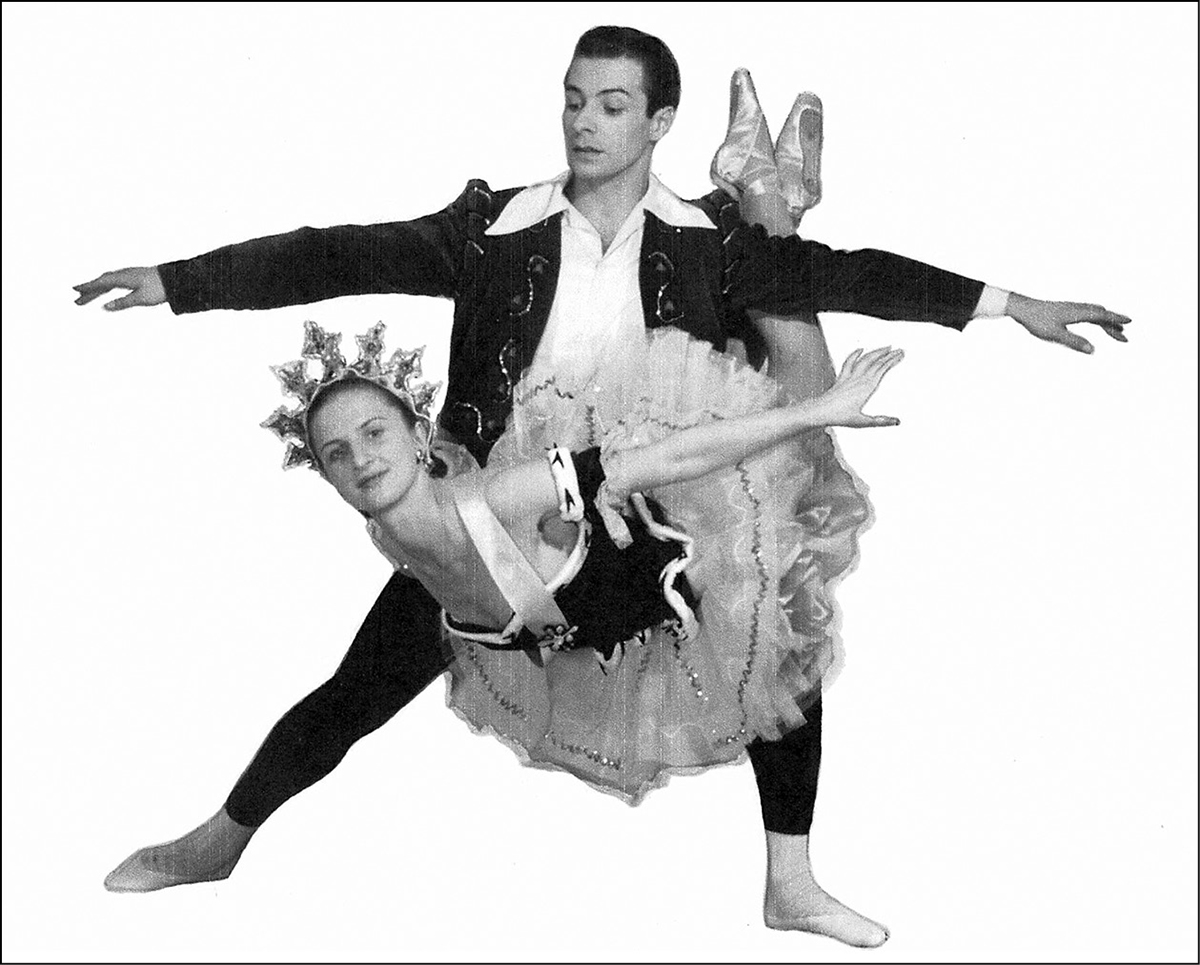

Irene Apiné and Jury Gotshalks in Coppelia, 1953. Photo: Ken Bell.

Courtesy: National Ballet Archives.

Irene Apiné and Jury Gotshalks in The Nutcracker, 1952. Photo: John Grange.

Courtesy: National Ballet Archives.

IRENE APINÉ AND JURY GOTSHALKS

IN 1952, JURY AND IRENE WERE DANCING the Don Quixote pas de deux for the first time in rehearsal in St. Lawrence Hall on King Street West in Toronto. The two were preparing for the first performances of then newly formed company, the National Ballet of Canada. They danced explosively with acrobatic choreography, multiple turns, and daring lifts. This was new and exciting, a style we had not yet seen within the Company.

Celia Franca had invited the pair to join the group from Halifax where they had lived on arriving in Canada from Riga, Latvia. Jury was instantly cast as the Tartar Warrior Chief in the Polovtsian dances from the Russian opera, Prince Igor, an important ballet on the company’s opening night. Jury was charismatic, handsome, and an excellent partner, especially for his wife, Irene Apiné. We were shaken by their work, their demanding personalities, their aloofness. They were bravura dancers and one felt both cursed and blessed by their pyrotechnic style. I felt a sense that they wanted to assimilate but just could not take that leap; we were so young and inexperienced compared to them. They were too European. After all, they had been leading dancers in the Latvian National Ballet. They had been forced out for political reasons and were unable to dance, either at all, or at their technical, professional level. The National Ballet of Canada was an opportunity for them to recreate and reinvent themselves as thrilling leading dancers of this new Canadian company. Irene was a high-energy, daredevil ballerina. She was beautiful and in all her roles sought the extra high arabesque, or the longer held balance. I loved their Slavic insolence. They were a great addition to the early days of the National Ballet of Canada, but as the repertoire changed, their bravura style was no longer appropriate and subtler ballets like Offenbach in the Underworld took over.

—Judie Colpman

MARY MCDONALD

MARY MCDONALD WAS A MUCH BELOVED accompanist of thirty-five years with the National Ballet of Canada. Peter Ottmann was only ten years old when he first performed in a production of The Nutcracker. He remembers Mary McDonald as a cheerful, motherly figure who made the children feel less lonely, fed them candies, and pinched their cheeks with her strong pianist fingers!

Mary was a wonderful musician and would often play four-handed piano with Celia Franca, who was highly musical herself. As principal pianist, she helped nurture the talent of many young dancers and won the hearts of every visiting artistic director or guest artist including the likes of Sir Frederick Ashton, Anthony Dowell, Rudolf Nureyev, Eric Bruhn, and many, many more. She toured extensively with the Company, accompanying some of the world’s most renowned performers, from Karen Kain to Rudolph Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov. While on a trip to Russia in 1973, accompanying Kain and Frank Augustyn at the Moscow International Ballet Competition, Mary was given the top award as pianist, ahead of pianists from twenty-two other countries.

Mary followed pianist Reg Godden in playing Rachmaninoff’s highly challenging second piano concerto for the ballet, Winter Night. She was endlessly patient when providing accompaniment during rehearsals, given the countless repetitions required. She had a close attachment to dancers taking the floor and saw it as her duty to merge her music with their movements as seamlessly as she could. Mary had high standards and strong opinions about striving for excellence. If an artist, a dancer, a musician, or conductor was not giving their best, she had something to say about it. These were the only moments she wavered from her gregarious and bubbly spirit.

Mary was above all a great believer in and encourager of dancers. Her attitude provided a rare reprieve in a culture that thrives on punitive pedagogies. Mary was amazingly modest, never assuming that she deserved any credit for the Company’s successes, though she did indeed. She was a kind, generous, and loving person. She will always be greatly missed by all of those her music and spirit touched.

—Jocelyn Terell and Peter Ottmann

GEORGE CRUM

THE ONE THING ANYONE WHO KNEW George Crum would remember about him was his love of telling jokes. Give him five seconds of your time and he would be asking you, “Did I tell you the one about…?” His face would already be crinkling up in anticipation of sharing your laughter. Never missing a beat once started, he would often break up, tears welling in his eyes, scarcely getting to the end of the story.

Beyond his humour, George Crum was multi-talented, his position as first conductor of the National Ballet only one of his many virtues. Absorbing his love of opera was something I did really appreciate. Along with his wife, Pat, and my husband at the time, Dick Butterfield, I enjoyed many an evening listening to Verdi and Puccini operas while George pointed out musical nuances that made the soaring music all the more moving. George’s introduction to this magnificent art form added a dimension to my life that I am ever grateful for, and value to this day.

George’s talents found other outlets as well. He was a superb craftsman in woodworking and took pleasure in designing beautiful bowls and boxes, a sampling of which I’m fortunate to have in my possession. His creative spirit was infectious and he would sit for me during tour stops while I drew portraits of him. Aside from his various artistic endeavours and his excellence as a conductor, George was also an avid golfer and billiards enthusiast—his interests ran the gamut.

George never tired—at least it seemed that way—of the endless repetitions of The Nutcracker, Les Sylphides, Gala Performance and other ballets that comprised our small repertoire in the early days. With his eyes always on the dancers to follow our lead, he seldom gave us the wrong tempo and, if he did, would be quick to change it for the next time around. With his patience and sincere interest in helping us do our best, George was the perfect dancers’ conductor.

I am sure that many dancers from those early days have their own personal memories of George, but one that I’m sure all of us remember is the time a piano he was helping to move fell on his foot and broke it. Undaunted, he cheerfully conducted through the following weeks with a cast on his foot; neither the dancers nor the audience were negatively affected. George always gave his best and lived up to the unspoken motto, as did the rest of us, that “the show must go on, regardless.” Jocelyn Terell adds: “One of George’s favourite jokes was about the conductor asking the ballerina each night if she wanted the music too slow or too fast. He told me that one often!”

—Lilian Jarvis

NORMAN CAMPBELL

NORMAN CAMPBELL WAS A DISTINGUISHED television producer who was much beloved by National Ballet dancers. He was a director whose credits ranged from episodes of All in the Family and the Mary Tyler Moore Show to musical variety specials and opera. However, it was as a director and producer of televised ballet for the Canadian Broadcasting Company that he made a special mark and contributed enormously to the early success of the National Ballet of Canada. Over the years he produced and directed sixteen full-length ballets by the National Ballet of Canada, as well as The Looking Glass People, a program about the Company, and numerous variety shows and specials that featured members of the Company. His work won two Emmys, one in 1968 for Cinderella, and one in 1972 for The Sleeping Beauty, as well as the prestigious Prix Rene Barthelemy in 1966 for Romeo and Juliet, all danced by Veronica Tennant.

At university, Campbell majored in math and physics to become a meteorologist. He also became involved in university theatricals. He only studied music for a few years, but he was a natural musician and composer. While working on Sable Island in Nova Scotia, he composed songs and photographed the wild horses, selling these photos to Saturday Night and The Saturday Evening Post. His appreciation of dramatic narrative, natural musicality, and a photographer’s eye, eventually brought him to the adaptation of classical ballet for the television screen. The CBC producer and director, Eric Till, described another gift that Campbell had, “the common touch … that extraordinary instinct of reaching an audience.”

In 1956, CBC supervising producer Robert Allen sought the advice of fellow CBC producer Eric Till on the future programming of ballet. Till advised him, “Since you get criticized for not doing it, why don’t you go after the biggest audience you can get and put on the greatest warhorse of all ballets which never fails to attract a huge audience—do Swan Lake!” Till was charged with calling Celia Franca, the founder and artistic director of the National Ballet of Canada, to determine if she could do a ninety-minute Swan Lake. According to Till her response was, “Of course I can!” Norman Campbell was given the job of producing his first Swan Lake.

Celia Franca was interested in television for two reasons. “My concerns with Canadian television were—in addition to the artistic ones—with securing extra employment for our dancers and with reaching a larger audience than the ballet could command in theatres” (Bell 136). Franca was astute enough to recognize that television could give the Company exposure that would be impossible to duplicate through performing and touring.

The resulting 1956 production of Swan Lake was broadcast live and its importance for the National Ballet cannot be underestimated. The actor, Barry Morse, introduced the programme and prior to each act gave a brief synopsis of the narrative. Before the fourth and final act, he also commented on the history of the National Ballet then added: “Tonight represents another milestone in the history of Swan Lake. This is the very first time that all four acts of the ballet have been presented on North American television and it should be a matter of pride for all Canadians that our National Ballet Company is one of the very few ballet companies in the world to have the full-length version in its repertoire” (Campbell).

The broadcast not only reinforced the Company’s prestige, but also its claim to being a national company. Campbell would go on to produce and direct the Company’s television productions of Coppelia, The Nutcracker, Pineapple Poll, a second version of Franca’s Swan Lake, Giselle with Lois Smith, Romeo and Juliet, Erick Bruhn’s Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, Giselle with Karen Kain, La fille mal gardée, Onegin, The Merry Widow, La Ronde and Alice.

Celia Franca summed up Campbell’s contribution to the National Ballet well when she said, “Mr. Campbell has contributed more towards exposing the National Ballet to the Canadian public than any of us. He is an artist of ability, taste, imagination, discrimination, honesty, and humour. He has the respect and affection of all who work with him—cameramen, technicians, make-up artists, designers, musicians, dancers and choreographers. His unfailing instinct enables him to bring out exactly the right dynamics in a dramatic or humorous situation and while he believes (as indeed I do) that when ballet is transferred to the screen, the vocabulary of the television medium should be used to the full, he always has respect for the choreography and never distorts the dance form for the sake of gimmickry” (Franca 7).

—Cheryl Belkin Epstein