“Pap?” I called, poking my head inside the shop. Pap stood at his bench, gluing up boards. “Pap, can I use some of your wood to build a house for Sable?”

“Sorry, Tate,” Pap said, shaking his head. “This wood’s too good for any doghouse.”

I guess I knew he wouldn’t let me. About all Pap ever lets me use are his stickers. Those are the strips he puts between planks when he’s drying wood. He’s got a lot of stickers, but I couldn’t figure how to build a doghouse out of them.

“Come on, girl,” I called to Sable.

We hunted in the shed behind Pap’s shop. Dressers, and bed frames, and boxes of canning jars leaned against the rough pine walls. I swiped at spiderwebs. “There must be something in here we can use for you,” I told Sable.

She turned her head in my direction. I wiped my dusty hands on the seat of my pants and stooped down. Holding Sable’s brown jaw in one hand, I stroked the top of her bony head with the other. She still wouldn’t look right at me.

“I’ll figure out something for you, girl,” I whispered. “Don’t worry.”

I’d hoped to find a big empty carton I could maybe cut a door into. Or a wooden crate. All I found was a worn-out cardboard box; it didn’t even have the flaps that make the top.

“Well, this will have to do,” I said. “It’ll make a good bed at least, Sable. Hold on. I’ll clean it up for you.”

I knocked the dried leaves and dead bugs out of the corners. Then I turned the box upside down and banged on the bottom, raising a puff of dust.

Sable sneezed. I sneezed, too.

“We need something soft to put in here, don’t we, girl?” I asked. “It’s not really a bed until it’s soft.”

I thought Pap’s sawdust might work as bedding. I led Sable back around to the shop.

Pap’s piles of sawdust were stacked up like fine raked leaves. I wished I could jump in those piles, but Pap’s broom was always leaning over them, just daring me to try.

“What you doing out there in the shed, Tate?” Pap asked.

“Just looking around,” I said.

“Don’t be making a mess, girl,” Pap warned.

“No, sir.”

I stood, staring at Pap’s back. His dark hair poked through the hole above the plastic snaps in his baseball cap.

“Pap, can I use some of your sawdust?” I asked.

Pap nodded, not even looking over at me. “Just don’t trail it across the floor,” he said. “And shut that door behind you, Tate.”

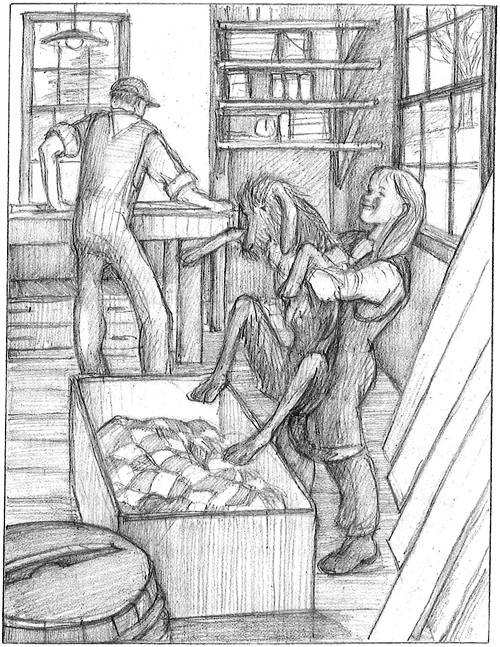

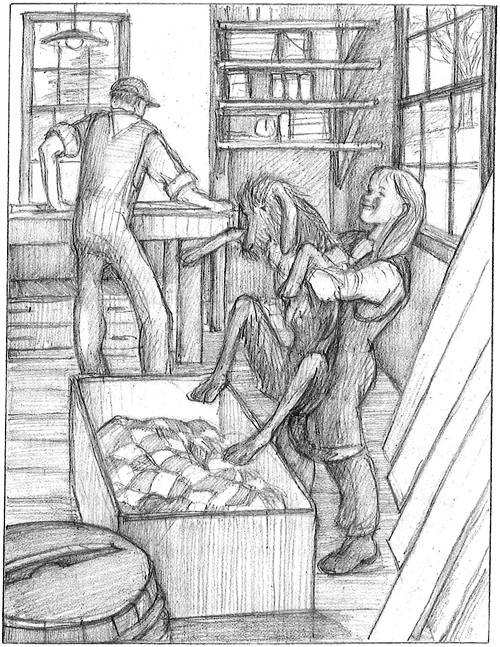

I closed the door and knelt in front of the tallest pile. Using my hands, I scooped sawdust into Sable’s box. Sable pushed her nose into the middle of things, helping.

“Okay, girl,” I said, standing up and brushing dust off my knees. The sawdust reached about halfway up the box sides. “Come on. Try it out.”

I pushed the box right in front of her.

Sable stared at me. Then she stared at the box. Instead of climbing in, she walked right past it, plopping down on the hard shop floor.

“Not there, Sable,” I said. “In your bed.”

Sable dragged herself up onto her feet again. She had sawdust all over her newly brushed fur.

“I should put something on top of the sawdust, shouldn’t I, Sable?”

I remembered the old stained quilt from Grandmam Betts. It wasn’t nice enough to put on a bed anymore. But it would do all right for Sable.

“Can Sable stay in here a few minutes?” I asked Pap.

Pap nodded, too busy working to notice what I was up to.

“Okay, girl,” I said. “Stay right here.”

Sable sank to the floor again, sweeping sawdust with her tail as I backed out of the shop.

I climbed silently onto the back porch. Mam stood in the kitchen, listening to the radio, her sleeves pushed up past her elbows. The muscles worked in her long back as her fist kneaded dough.

Slipping around to the front of the house, past Mam’s willow, I let myself in quietly. I crept up the stairs, careful to skip the creakers. My heart hammered against my throat. Mam would sure explode if she caught me giving Sable one of Grandmam Betts’s quilts, even a ruined one. I managed to get the quilt down from the closet and out of the house without Mam knowing.

Pap looked up as I rushed through the shop door. My hair crackled, full of static from carrying the quilt on my head.

“Does Mam know you have that blanket?” Pap asked.

“No, sir,” I said.

Pap nodded. “She’s not going to like it.”

“I didn’t take a good quilt, Pap,” I said.

“She’s still not going to like it.”

I folded and refolded the blanket, till I got it just right in Sable’s box. “Okay, girl,” I said. “It’s ready now. Hop in.”

Sable backed away from the box, her tail between her legs. I climbed inside it myself, showing her what to do.

“This is your bed, Sable.”

She just sniffed inside my ear.

Finally I gave up trying to coax her. I just picked her up and put her in. For such a big dog, Sable weighed about as much as an empty school bag.

She stood on the quilt for a few seconds, looking wobbly. Then she sniffed the fabric, pawed some wrinkles into it, circled, and dropped her bones down.

Sable sighed, real long, like wind down a chimney. She rested her head on the edge of the cardboard box.

“Can we keep Sable’s bed in your shop tonight?” I asked Pap.

Pap looked over and frowned. “We don’t even know if that dog’s housebroken, Tate. If she messes anything—anything,” he said, “you’re responsible.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

I explained to Sable how she was a guest in Pap’s shop. “You better behave,” I told her.

* * *

Cooking up a pan of mush for Sable’s supper, I stirred a spoon of bacon fat in to improve the flavor.

Sable ate her mush out on the porch, licking the bowl over and over, chasing it around with her tongue, until finally I took it away. Then I led her back toward Pap’s shop. She didn’t wait to be invited. She headed right inside out of the shivery cold as soon as I opened the door and clicked on the light. She climbed straight into her box.

“Don’t get comfortable yet,” I said. “Remember, Sable, no messes in this shop.”

I led her back outside, standing in the patch of light from Pap’s shop window, hopping up and down to keep warm. Sable didn’t make me wait in the cold for long.

“You’re a good dog,” I said, hugging her skinny brown neck.

Sable smelled like dried leaves, and dust, and pine trees. Her warm breath tickled inside my ear. I buried my face in her dark coat, breathing her in. Sable stood still, her tail swaying gently behind her.

“Into bed now,” I said. I fingered those ears of hers one more time. The white tip of her tail twitched against the side of her box. There was no room in her bed for a full tail wag.

Holding her face between my hands, I concentrated on fixing everything about her in my mind.

“Sable,” I whispered.

For the first time she looked straight at me. Her eyes shone like chocolate melting in the pan, all liquid and warm and sweet.

A bubble of something joyous lifted inside me.

“Don’t get into trouble tonight, Sable,” I said. “Promise.”

And be here in the morning, I prayed as I turned out the light and shut the shop door behind me.

That night I stared across the starlit yard. There was a dog sleeping in a cardboard box in Pap’s shop. A real dog. Tomorrow I’d bring money to school and scoot over to Tom’s General Store. I’d buy real dog food for Sable. When I got home, I’d teach her to sit, and stay, and roll over.

Mam and Pap hadn’t said I could keep her.

But they hadn’t said I couldn’t, either.