We don’t progress because we play the same things every time we play somewhere. We used to improve at a much faster rate before we ever made records. You’ve got to reproduce, as near as you can, the records, so you don’t really get a chance to improvise or improve your style.

—GEORGE, 1965

A black Austin Princess limousine with tinted windows pulled out of William Mews in Belgravia on the morning of Thursday, December 2, and turned right into Knightsbridge, driving past Harrods toward Hyde Park Corner. In the front was thirty-seven-year-old chauffeur Alf Bicknell, bespectacled and wearing a formal gray suit and tie. On the other side of the glass partition behind him were five young men sitting in two rows: Ringo Starr, George Harrison, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and their personal assistant / road manager, Neil “Nell” Aspinall, who they’d known since their early days in Liverpool when they were a local beat group and he was training to be an accountant.

Traveling up Park Lane they could see on their right the twenty-eight-story tower of the Hilton Hotel (the third tallest building in the capital), which had opened two years before, the first in Britain built by an American hotel chain and a convenient symbol of the new, modern London. Close by was 45 Park Lane, where Playboy was soon to open a new club.

At Marble Arch, the car turned into Edgware Road and slid toward Maida Vale and St John’s Wood, where they were just yards away from the EMI Recording Studios on Abbey Road, the building where every Beatles song from “Love Me Do” in 1962 to the just-released double-A-sided single “We Can Work It Out” / “Day Tripper” had been recorded.

They were heading out to the start of the M1 motorway, the first dual three-lane highway linking the south of England with the north. There were still only 360 miles of motorway in the country, and city bypasses accounted for much of this. To travel long distances by road in Britain still meant driving on category-A roads that often had only two lanes, were unlit at night, had no hard shoulders to pull onto in the case of emergencies, and frequently twisted and turned. The only refreshment stops were at cheap cafés, designed for long-haul lorry drivers and where there was dark brown tea, a selection of stale sandwiches, a jukebox, and possibly a pinball machine.

Ahead of them was a 350-mile journey to the north of England, where they would stop overnight before driving into Scotland for the first of their nine-date 1965 tour of Britain. Probably already there by now was Mal Evans, their other road manager, who’d set out the night before in the van with seven electric guitars and the amplifiers, leaving behind only the acoustic guitars the Beatles used for rehearsals and songwriting.

Almost two weeks before, on November 20 and 21, they’d had a full-scale practice at the Donmar Rehearsal Theatre on Earlham Street, Covent Garden, a space used by ballet companies, opera houses, and theatres to develop new productions. The four of them had stood facing each other, dwarfed by the vast empty space, with only their instruments, some speakers, chairs, and a table for refreshments and ashtrays. The lights were dimmed. To the side of the electric piano was a copy of the new LP B. B. King Live at the Regal, which had been recorded almost exactly a year ago in Chicago.

The Beatles rehearsing for their final UK tour at the Donmar Rehearsal Theatre in London, November 20, 1965.

Getty Images/Robert Whitaker

They finalized eleven songs that would make up their thirty-five-minute set. Boldly, they had chosen to leave out their traditional barnstormers such as “Please Please Me,” “She Loves You,” “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” “I Saw Her Standing There,” and “Twist and Shout” to concentrate on songs released over the past twelve months. They planned to start with “I Feel Fine” and follow with its B-side, “She’s a Woman,” George’s “If I Needed Someone” (just covered by the Hollies), Ringo’s vocal number “Act Naturally,” and John’s more introspective “Nowhere Man.” The show would continue with “Baby’s in Black,” “Help!,” “We Can Work It Out” (with John on keyboards), “Yesterday” (with Paul on keyboards), the new single “Day Tripper,” and end triumphantly with Paul’s Little Richard pastiche “I’m Down,” successfully used as a closer during their tour of America in August.

This was the first year they’d played so few dates in their home country. In 1962 they’d played 188; in 1963, 117; and in 1964, 50. In the early days, when their fame was limited to the Merseyside area, it wasn’t unusual for them to play three gigs in a day—a lunchtime appearance at the Cavern Club followed by two evening shows elsewhere in Liverpool. This decrease was because of their choice to limit touring in general and also the need to satisfy demand in other territories. The bigger they became, the less significant the home market was in terms of concert revenue.

Thursday was the day that Britain’s music papers reached the newsstands. These papers played a vital role in building excitement about the new beat music: exaggerating rivalries between various groups, introducing new acts, and keeping music fans well informed about musical developments. They all featured the latest news, charts of the bestselling singles and LPs, interviews with pop stars, record reviews, ads, and gossip.

There was the long-established Melody Maker with its bias toward jazz and serious musicianship, as befitted its origin in 1926; New Musical Express (NME), which focused more on pop, as befitted its origin in 1949; Record Mirror, which pioneered appreciation of American R & B; Music Echo, which was what the Liverpool fan paper Merseybeat had turned into; and the more chart-oriented Disc. The combined sales of these papers was well over half a million copies, and most young people in Britain got their pop education from them, along with girls’ comics such as Boyfriend and Valentine, unisex teenage magazines like Rave and Fabulous, the European radio station Radio Luxemburg, and the new “pirate ships” Radio Caroline and Radio London. The pirate ships outwitted Britain’s ban on commercial radio and the subsequent monopoly of the airwaves by the BBC by broadcasting from just outside British territorial waters and introducing twenty-four-hour pop and American-style DJ patter after decades of fairly prim officially sanctioned presentation.

On this day, as the Beatles headed north on the motorway, the early verdicts on both the LP Rubber Soul and the single “We Can Work It Out” / “Day Tripper” were out, Friday being the official release date for both records. The music press had been integral to the group’s rise, and the group had developed close relationships with its younger reporters, who often traveled with them. But some of the older writers, who’d grown up on music by Frank Sinatra and Count Basie rather than Elvis and Buddy Holly, didn’t fully comprehend what was going on. NME’s Derek Johnson, who was thirty-seven, described “Day Tripper” as having a “steadily rocking shake beat” and decided that it was “not one of the boys’ strongest melodically.” “We Can Work It Out,” on the other hand, with its “mid-tempo shuffle rhythm” was, he thought, “more startling in conception.”

Allen Evans, who’d been writing for NME since 1957, was equally restrained in his review of Rubber Soul, concluding merely that it was “a good album with plenty of tracks you’ll want to hear again and again.” His song-by-song descriptions left much to be desired. “Norwegian Wood” was a “folksy bit of fun by John,” and the music of George’s sitar was misidentified as “Arabic-sounding guitar chords.” “Nowhere Man” reminded him of the Everly Brothers, and “The Word” of gospel music. “What Goes On” was “jogging” and “tuneful,” “I’m Looking Through You” was “a quiet, rocking song,” and “Wait” was a “jerky” song. His entire description of John’s breakthrough composition “In My Life” was “A slow song, with a beat and spinet-sounding solo in the middle. Song tells of reminiscences of life.”

Record Mirror concluded, “One marvels and wonders at the constant stream of melodic ingenuity stemming from the boys, both as performers and composers. Keeping up their pace of creativeness is quite fantastic. Not, perhaps, their best LP in terms of variety, though instrumentally it’s a gas!” Melody Maker declared after one hearing that Rubber Soul was “not their best.” Its reviewer thought tracks like “You Won’t See Me” and “Nowhere Man” were monotonous. “Without a shade of doubt, the Beatles sound has matured but unfortunately it also seems to have become a little subdued.”

The Beatles were frustrated that pop music journalism had not caught up with what they were doing. The reviewers had neither the critical vocabulary nor the broad musical perspective to evaluate the advances that they were making in the studio. If songs weren’t pounding, head-shaking rock numbers or toe-tapping melodies, the writers concluded that the band was slipping or becoming complacent. A month before, speaking to Keith Altham, one of NME’s new generation of writers, John had reluctantly conceded, “There are only about a hundred people in the world who really understand what our music is all about.”

By late 1965 the British press was anticipating, not without a smidgen of relish, that the Beatles might be nearing their end as the Kings of Pop and so were scrutinizing the group’s output and image, as well as the behavior of fans, for the first signs of decline. Two to three years was the predicted lifespan of pop stars dependent on a largely teenage market. After this they either diversified into film actors and “all-round entertainers” or risked turning up in “Where Are They Now?” columns.

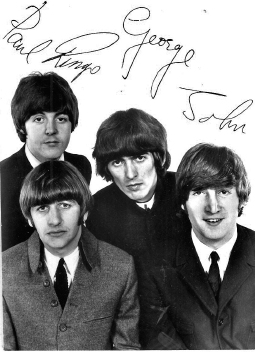

A machine-autographed publicity photo for the Beatles, late 1965.

Steve Turner Collection

British pop history was littered with people who had shone for a few singles and then either retired, hit rock bottom, or tried to woo the parents: the Vipers, the King Brothers, the Mudlarks, Terry Dene and the Dene-Agers, Emile Ford and the Checkmates, Tommy Bruce and the Bruisers. Because of this, the Beatles were frequently asked what they would do once the “bubble has burst,” and none of them doubted that this was the inevitable end. John and Paul imagined their future selves as songsmiths smoking briar pipes and wearing tweed jackets with leather arm patches, and they were already writing material for other artists with this end in view. Pop stardom was transient, but songwriting was a worthy profession that involved people of all ages. For George and Ringo, putting their earnings in a business was regarded as the most sensible move.

Initially, there was no planned winter tour of Britain, because the Beatles were due to make a movie in Spain for Pickfair Films Limited, a company set up by their manager Brian Epstein and George “Bud” Ornstein, the former European head of production for United Artists films. According to press releases, this was outside of the Beatles’ three-film deal with United Artists. Ornstein was a nephew of the actress Mary Pickford, who helped found United Artists in 1919 with Charlie Chaplin, D. W. Griffith, and Douglas Fairbanks, and Pickfair had been the name of the Pickford-Fairbanks studios.

Epstein, who’d spent a year studying at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts in London, was a great lover of theatre and film and particularly enjoyed it when his pop management brought him close to the world of actors, directors, and producers. The world of beat music and screaming teens was not his natural milieu. He was happier with classical music, ballet, and Broadway.

In February 1965, Pickfair had announced that it had commissioned Richard Condon, the American author of the 1959 bestseller The Manchurian Candidate, to produce a screenplay of his 1961 Western novel A Talent for Loving. The month before, John had invited the Geneva-based Condon out to St. Moritz, where John and his wife, Cynthia, were vacationing with producer George Martin and his then mistress, Judy Lockhart-Smith. According to Condon, John wanted him to recount the whole story so that he could be sure of getting a plum role (and wouldn’t have to read the book). Then the group had doubts about Condon’s script, and Epstein announced that they were delaying a planned autumn shoot due to the unpredictability of the Spanish weather, not a plausible excuse. This allowed for a short tour to be scheduled, the first in Britain for a year.

Compared to tours nowadays that involve months of rehearsals, containers full of equipment, light shows, complex staging, security teams, and hundreds of technicians, caterers, assistants, drivers, and media managers, the Beatles’ 1965 tour of Britain looks positively primitive. The entire road team consisted of Mal Evans, Neil Aspinall, Brian Epstein, publicist Tony Barrow, and chauffeur Alf Bicknell. Promoter Arthur Howes came to some of the shows with his secretary, Susan Fuller.

They arrived at Berwick-upon-Tweed in Northumberland, three miles south of the Scottish border, under the cover of darkness and checked in for a night’s sleep at the King’s Arms Hotel, an eighteenth-century coaching inn close to the river at the center of the town. The staff and local police had been advised of the visit but were sworn to secrecy. As a result the rest of the town knew nothing about it until a week later when the Berwick Advertiser ran a story headlined “Beatles Came in Night and Slipped Away” with an accompanying photo of John, George, Ringo, and driver Alf Bicknell descending the hotel’s main staircase.

The next day the Beatles slept late, had breakfast in bed, and then left at lunchtime dressed in thick, dark coats over jackets and turtlenecks (except for Paul, who wore a shirt and tie) and carrying small overnight bags. During the 130-mile trip from Berwick to Glasgow in driving rain, one of George’s guitars, a £300 Gretsch Country Gentleman, fell from its position strapped to the trunk and into the path of traffic behind them. It was hit by a truck and wrecked. Years later George attributed the event to karma, though he didn’t take it so philosophically at the time: “Some people would say I shouldn’t worry because I could buy as many replacement guitars as I wanted, but you know how it is. I kind of got attached to it.” The only consolation was that it wasn’t the guitar he played on stage.

John, followed by Ringo, George, and driver Alf Bicknell, leaving the King’s Arms Hotel, Berwick-upon-Tweed, December 3, 1965.

Berwick-upon-Tweed Record Office

Once in Glasgow they checked into the Central Hotel on Gordon Street, and at 5:10 (seventy minutes late) were ready at the Odeon for their first press conference of the tour. John was wearing his trademark Greek fisherman’s cap, Ringo had on the brown suede jacket he’d worn for the cover shoot of Rubber Soul, George wore a baggy gray turtleneck pullover, and Paul sported a black collared button-down shirt with a floral “mod” tie bought a week earlier during a three-hour private shopping spree at the Harrods department store in Knightsbridge.

Q: How do you feel at the start of another UK tour?

JOHN: It’s funny. It’s always the same at the start of a tour. We are nervous. But, once we get on stage, it all goes.

Q: Why did you drive up to Glasgow instead of flying?

JOHN: We don’t like flying. If we can go by road, we do. We’ve done so much flying without really having any accidents, so that the more we do, the more we worry. I suppose we think that, sooner or later, something might happen.

Q: What about having the Moody Blues on tour with you?

GEORGE: We’ve always been good friends with them. We seem to get on well. I don’t think we specifically asked for them, but I know we all agreed when their name was mentioned. They go down well with the kids. Their style is different to ours, but we follow the same trends.

As with all the dates on this short tour, there were two evening shows in Glasgow, and the Beatles were supported by four groups—the Moody Blues (including Denny Laine, who would go on to be a member of Wings), the Paramounts (whose keyboard player, Gary Brooker, would form Procol Harum), the Marionettes (featuring Trinidad-born vocalist Mac Kissoon), the Koobas from Liverpool, and two solo acts from Liverpool—Beryl Marsden and Steve Aldo—who were backed by the Paramounts. An MC from Sheffield, Jerry Stevens, introduced each act and told jokes as the stage was set up between performances.

There wasn’t the normal fraternizing associated with tours. The Beatles always had a separate dressing room, the groups stayed in different hotels according to what they could afford, and everyone made it to the venues with their own transport. After each show the Beatles were bundled off so quickly to an awaiting car that the Koobas never had the chance to talk to them until they went to a club after the last of the London concerts.

Exclusive access to the tour was given to twenty-five-year-old New Musical Express reporter Alan Smith, who’d been interviewing the Beatles since early 1963. The same age as John, and brought up on the other side of the Mersey in affluent Birkenhead, he was more attuned to the group’s music and social origins than most journalists. He stayed with the tour for a few days in the north and then rejoined it when it reached London. He socialized with them in their dressing room at Glasgow’s Odeon, listening to them discussing work and watching John carefully disarrange his hair before showtime (“It takes me hours to look this scruffy”). He concluded that they were a lot more serious than they had been on previous tours. They were calmer and more mature. There was less joking, drinking, and partying.

This may have been due to the fact that they’d replaced drinking with pot smoking. When they arrived at a theatre they would seek out an empty, unused room in the backstage area and disappear with Steve Aldo to have a smoke before the show. This was extremely risky at the time. A pop star caught with pot would have been as scandalous as one found with heroin today, and since pot smoking was so out of keeping with their clean and cheerful image, the Beatles’ reputation would have been irreparably damaged.

The calmness may also have been a result of accepting their lot in show business life. They had wanted to ascend to the “toppermost of the poppermost” (as John would jokingly describe it in the days when they traveled in the back of a van along with their equipment), make lots of money, and become bigger than Elvis, and now that they had achieved these things, they found themselves prisoners of their own adolescent dreams. They had achieved their early ambitions, and yet their freedom of movement was now restricted because of their fame, their musical development was impeded by not being able to hear themselves play, and the sheer joy that they had experienced on stage when unknown was fast evaporating.

Fifteen years later, in one of his last interviews, John said, “The idea of being a rock ’n’ roll musician sort of suited my talents and mentality, and the freedom was great. But then I found out I wasn’t free. I’d got boxed in. It wasn’t just because of my contract, but the contract was the physical manifestation of being in prison. And with that I might as well have gone to a nine-to-five job as to carry on the way I was carrying on. Rock ’n’ roll was not fun anymore.”

There were conflicting reports about the intensity of Beatlemania as 1965 drew to a close. Newspapers had a vested interest in keeping the phenomenon alive (it spiced up news and sold copies), but they also wanted to be the first on the scene when it began to experience its death throes. The unspoken rule was that those who benefitted from huge acclaim, financial reward, and natural talent should eventually suffer for their success.

On December 4, the Daily Mirror reported that 131 teenage girls had to be treated by ambulance staff during the two Glasgow shows and that six fans were taken to the hospital—a third of the casualties had fainted, and two-thirds had succumbed to “hysteria.” It said that there had been “a continuous chorus of screaming,” at times so loud that the music was drowned out. Alan Smith, however, heard the same screams and judged that they were less intense than at past shows. “Crazy Beatlemania is over, certainly,” he would conclude in his December 10 report. “Beatles fans are now a little bit more sophisticated than Rolling Stones followers, for instance, and there were certainly no riots at the Glasgow opening night. But there were two jam-packed houses, some fainting fits, and thunderous waves of screams that set the city’s Odeon theatre trembling.”

If the fans were screaming at lower volumes and fainting in smaller numbers, it may have been because of the Beatles’ change of material. “People who expect things to always be the same are stupid,” Paul told Smith. “You can’t live in the past. I suppose things would be that little bit wilder if we did big raving, rocking numbers all the time, just like we did at the beginning. But how long could we last if we did that? We’d be called old fashioned in no time. And doing the same thing all the time would just drive us round the bend.”

The next day began with a 150-mile drive to Newcastle, where they checked into the Royal Turk’s Head Hotel on Grey Street. At the venue, City Hall, they were given a darkened TV room next to their dressing room to relax in. When they weren’t on stage, they watched the Saturday night ITV schedule, including the American TV series Lost In Space, an episode of The Avengers starring Patrick Macnee as John Steed and Diana Rigg as Emma Peel in which the duo tracked down a criminal businessman who was bumping off financiers through use of new-fangled paging devices that triggered heart attacks (“Dial a Deadly Number”), and an edition of the light entertainment show Thank Your Lucky Stars, presented by Jim Dale, in which the Beatles were featured in a film clip playing “We Can Work It Out” and “Day Tripper.” Other guests included Tom Jones, the Shadows, the Kinks, Dennis Lotis, and Mark Wynter.

The clips had been filmed at Twickenham Film Studios on November 23 and were intended to satisfy the demand of TV stations without the group having to sacrifice time by traveling to them all. It was a time- and cost-effective way of promoting their music while retaining control of presentation. All the clips were shot in the studio, and other than changing their clothes and the sets no effort at visual storytelling was made. Renting the set cost £750, and the BBC paid £1,750 for the rights to be the first to screen them. It was the birth of the promotional pop video, something the group would develop further in 1966. “We had great ideas for it,” John told Alan Smith. “We thought it was going to be an outdoor thing, and with more of a visual appeal. I’m not really happy the way it’s turned out, but it hasn’t put me off this kind of idea for the future. I’ve no objection to filming TV appearances. For a start, it means we can film them all in one day instead of traipsing round the country to do different programmes.”

The Newcastle dates were notable not for rioting or collapsing fans but for the showers of jelly beans and “gonks” (small egg-shaped novelty toys with frizzy hair) hurled onto the stage. Between shows the Beatles were served dinner and were interviewed by local newspaper journalist Philip Norman, who would much later become a staff writer with the Sunday Times and a celebrated biographer of the Beatles, John Lennon, and Paul McCartney. When the second show ended, they again retreated to the TV room to watch the play The Paraffin Season by Donald Churchill as part of the Armchair Theatre series, which had recently been moved from its coveted spot on Sunday night. Hotels in those days rarely provided in-room TVs, and one of the stars of The Paraffin Season, the Liverpudlian actor Norman Rossington, had acted with the Beatles the previous year in A Hard Day’s Night (where he played the group’s manager, Norm).

According to Alan Smith it was a quiet night, and the boys all returned to the hotel after the show. According to another source, some of them at least stayed up late, partying with the Moody Blues and playing LPs by the Isley Brothers and B. B. King.

The next day they rose late from bed and didn’t leave for Liverpool until 1:00 p.m. No other British city had seen more of the Beatles. Since the group’s earliest incarnation in 1957 they’d made over five hundred local appearances. Their uncles, aunts, school friends, parents, and cousins all still lived there, as did many of the fans who’d faithfully stuck by them in the days when they played cover versions and dreamed of international stardom. “Liverpool is home,” said John. “As they all know us, we’ll be expected to do well, and we’ll get nervous.”

The two shows they played at the Empire Theatre would be their last ever in Liverpool. The Empire had played a role at key times in their career. It was here that both Paul and George had seen the Canadian vocal quarter the Crew-Cuts in concert in September 1955, and where Paul had lined up at the stage door to collect their autographs. It was here that John had (unsuccessfully) auditioned with the Quarry Men for talent scout Carroll Levis in 1957 and John, Paul, and George had auditioned as Johnny and the Moondogs for Levis in 1959. In October 1962 it had been the scene of their first major theatre show, on a bill headlined by Little Richard. In December 1963 they’d played here before fan club members in a special afternoon event, part of which was screened on BBC TV as It’s the Beatles.

It was sadly appropriate that on the day of their final Liverpool engagement they were approached by fans campaigning to prevent the closure of the Cavern, the cellar club close to the docks where they’d played almost three hundred of their early gigs. The city council was demanding that it modernize its sanitation and drainage, but the owner couldn’t afford the expense. The Beatles were not about to bail out a failing business. As yet there was no Beatles tourist industry in the city, and no one was thinking of plaques, preservation orders, or the involvement of the National Trust. It was Paul who suggested that it could be turned into a local attraction, while John announced, “We don’t feel we owe the Cavern anything physical.” Two months later it closed down, and despite a brief reprieve it was filled in and covered by a parking lot in 1973.

As with the Glasgow concerts, the level of fan enthusiasm was hard to calculate. Careful policing prevented the street riots of previous years, and the count of fainters (a mere seventeen out of a total audience of five thousand) made it appear less hysterical in press reports, but the screaming and dancing in the aisles persisted. The noise was loud enough for Paul to ask anxiously whether his voice was being picked up by the microphones and for Ringo to comment later, “You heard them. You saw them. That’s the answer to the knockers who say we’re on the way out.” Yet Alan Smith could still write in New Musical Express: “Even in ‘the Pool,’ however, I noticed a quietening down of audience reaction compared with previous concerts. I’m not knocking in any way—I just think the group’s fans are getting a bit more sensible lately. There was tons of thunderous applause to compensate for the lowered screaming decibel rate!”

Friends and family were on hand to greet the group backstage, including the Labour MP for Liverpool Exchange, Bessie Braddock; the young comedian Jimmy Tarbuck, who had been at school with John; Ringo’s mother, Elsie, and stepfather, Harry Graves; and George’s parents, Harold and Louise, and his model girlfriend, Pattie Boyd, whom he’d met in 1964 on the set of A Hard Day’s Night. There had initially been plans for more shows that Monday, but the Beatles preferred time off to spend with relatives and friends.

The Beatles were proud Liverpudlians. Unlike previous generations of entertainers from the north of Britain they didn’t try to modify their regional accents or disguise their working-class roots. They loved the community feeling that had been fostered by hard times, the natural unpretentiousness, the droll sense of humor, and the cosmopolitanism that came from generations of immigration.

So much of what made the Beatles unique—their wit, their wordplay, their grass-roots left-wing sympathies—was an inheritance of having been born and raised in Liverpool. Yet Liverpool was also a place that young people with ambition like them strained to escape from. The people were warm and overwhelmingly working class, yet the architecture in the city center was austere and grandly imperial. There were exciting connections with the major ports of the world because of the ships that sailed from the Mersey, yet culturally it lagged behind the south. In the 1950s and early 1960s all of Britain’s regional cities were two to three years behind the capital when it came to trends in fashion and lifestyle. It was to London that the Beatles looked for all the latest changes in pop music and to London that they moved in the first year of their fame. Said George: “I get a funny feeling when I go back to Liverpool. I feel sad because the people there are living in a circle. They’re missing out on so much. I’d like them to know about everything—everything that I’ve learnt by getting out of the rut.”

As soon as they came into money Paul, George, and Ringo improved the lives of their parents by moving them out of their government-subsidized housing to large properties in more prestigious areas. Ironically, it was John, the “working class hero,” who had grown up in the most middle-class home, who moved his Aunt Mimi to one of the most expensive areas of Britain’s South Coast—Sandbanks, in Dorset. When he bought her six-bedroom house on Panorama Road in 1965, it cost eight times the average British home of the day.

Tuesday’s concerts in Ardwick, Manchester, were affected by bad road conditions. A heavy fog brought traffic on the Liverpool–East Lancashire Road to a standstill, and the Beatles didn’t arrive at the ABC Cinema until twelve minutes after they were due on stage. An extra interval had to be inserted to compensate, the support acts extended their spots, and MC Jerry Stevens was left frantically thinking of things to say to prevent fans from rioting.

From Manchester they moved on to the steel city of Sheffield, where they played the Gaumont Cinema on Wednesday, December 8, and then drove to Birmingham on December 9 to play at the Odeon. In Sheffield twenty fans fainted, and Paul was hit in the eye by a pear drop that left him blinking throughout the show. Fred Norris, the thirty-eight-year-old theatre critic for the Birmingham Evening Mail, summarized the Beatles’ thirty-minute set as “one long ear-aching, head-reeling blast” and said that the behavior of the fans ranked as some of the worst he’d ever witnessed. “If this is modern ‘live’ music,” he concluded, “one understands why The Beatles themselves spent most of their time backstage, watching television.”

When “We Can Work It Out” / “Day Tripper” reached only No. 3 on Melody Maker’s new chart (beaten out by the Seekers’ “The Carnival Is Over” and “My Generation” by the Who), the Daily Mirror headline was “Beatles’ New Disc Misses No 1 Spot” over a story that began, “A two year Beatles’ record went west yesterday. For the first time since December 7, 1963 a newly-issued single disc by the Merseysiders failed to fly automatically to No 1 in the Melody Maker pops chart.”

The Daily Express featured a subdued photo of John and Paul dressed in black next to the headline “From the Revealing Album of David Bailey . . . to Mark What Might Be a New Phase in the Era of the Beatles.” After making the same point as the Daily Mirror that the new single had “failed to reach the top spot” (despite making No. 1 on a rival chart by New Musical Express), show business correspondent Judith Simons posed the question “Does this mark a change in Beatlemania?” George Harrison didn’t think it did. He felt it was the result of marketing the single as a double A side, the first time any artist had done so. In the end “We Can Work It Out,” composed predominantly by Paul, was deemed the more popular song.

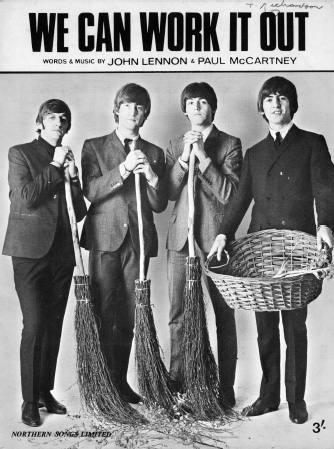

The double-A-sided single “We Can Work It Out” / “Day Tripper” made the British charts in December 1965.

Steve Turner Collection

Contained in these stories was other news that would reveal the deeper nature of what was happening. UK advance orders for the new LP, Rubber Soul, stood at five hundred thousand, almost the same as the number of singles that had been sold. It was, Simons noted, “believed to be the biggest ever advance demand” for a British LP. In other words, the big story wasn’t that the Beatles had failed to take the top spot of the singles charts immediately after their new release but that fans were now buying LPs in equal volumes. An LP by the Beatles was changing from something bought as a nonessential supplement to the singles—often as a special birthday treat or Christmas gift—to the very focus of their music-making career.

The pinnacle of the tour was the two London dates—the first at the Odeon Cinema in Hammersmith and the second at the Astoria Cinema in Finsbury Park. The expectation had been that these would be the toughest shows, because Londoners had more opportunity to see great entertainment and therefore prided themselves on their cool restraint. Audiences in the provinces were expected to go wild, but London fans usually made performers work hard for applause.

This time the opposite proved to be true. The audiences in both venues erupted. After the second show at Finsbury Park Alan Smith reported,

This was the wildest, rip-it-up Beatles performance I have watched in over two years. Girls have been running amok on the stage chased by hefty attendants. Some were hysterical and I have just seen one girl carried out of the theatre screaming and kicking and with tears streaming down her contorted face.

Finsbury Park Astoria holds 3,000 people and I swear that almost every one of them has been standing on a seat. Now, after the show, some of the seats in the front stalls lie battered out of existence. They tell me the hysteria and the fan scenes were even worse at Hammersmith last night. I did not think I would say this again but, without question, BEATLEMANIA IS BACK! Don’t get me wrong. In saying that, I have not been swayed simply by the screams. In the NME last week I told of the tremendous reception given to the Beatles in Glasgow, Newcastle, Liverpool and Manchester. But these London concerts were different. I have not seen hysteria like this at a Beatles show since the word Beatlemania erupted into headlines!

Backstage at Hammersmith the Beatles socialized with Gary Leeds and John Maus of the Walker Brothers, themselves now the object of screaming fans after the success of the single “Make It Easy on Yourself” and their debut LP, Take It Easy with the Walker Brothers. The Americans discussed the technical aspects of guitar playing with the Beatles, then watched the concert from the wings. After the show they accompanied the Beatles to the newly opened Scotch of St James, a club that had become the headquarters of London’s cool and fashionable elite.

Their final British tour date was at the Capitol Theatre in Cardiff on Sunday, December 12, the day after Finsbury Park. Toward the end of the second set there was a worrying incident when a man managed to get on stage while John was introducing “Day Tripper” and made a lunge for Paul and George before being grabbed by security guards. He was swiftly ejected, but it was a salient reminder of how vulnerable the Beatles were to attack.

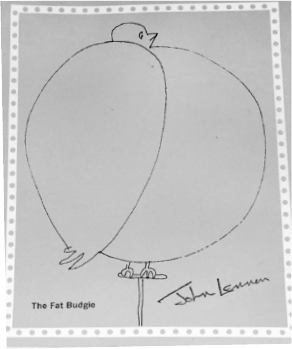

John was also involved in mild religious controversy. Oxfam had recently used his illustration accompanying his poem “The Fat Budgie” from A Spaniard in the Works, his second book of poems and drawings, for one of its 1965 Christmas cards. This didn’t go down well with some supporters of the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief (to give the charity its full title). They felt it was in poor taste to use a pop star’s cartoon of a budgie to celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ. One such opponent, Rev. Frederick Nickalls of Barnehurst, Kent, was quoted as saying, “The John Lennon card has nothing to do with Christmas. It is a pity that Oxfam should choose such a card. Those old world pictures of stage coaches, snow and candles are more Christian than The Fat Budgie.”

After the second show in Cardiff the Beatles got into the Austin Princess, and Alf Bicknell drove them out of the city, from where they were escorted by police cars and onto the road back to London. They were delivered to the Scotch, where they celebrated the end of the tour.

Paul returned to the Scotch the next night, December 13, for what would turn out to be a memorable occasion for him. John, Ringo, and George had taken LSD by this time and were enthusiastic about the way in which they felt the drug made them more creative, open-minded, and loving. They argued that it unleashed human potential by revealing how artificial many of the restrictions are that we place on our understanding. Their campaigning made Paul feel like an outsider. It was as though the three of them possessed some special knowledge and were leaving Paul behind. The closer that John got to George, the more of a threat it was to the Lennon-McCartney partnership.

An Oxfam Christmas card featuring John’s drawing “The Fat Budgie” from A Spaniard in the Works, December 1965.

Steve Turner Collection

Many others in Paul’s London coterie were converts to LSD, but Paul was cautious by nature. He’d heard the rumors of depression, schizophrenia, and madness that could be triggered by LSD and was reluctant to experiment foolishly with something as finely tuned and fragile as the brain. He was sensible, responsible, and loath to do anything that could damage his career or his mental health. He always remembered his father’s advice of “moderation in all things, son.” At the same time, he was adventurous and keen not to dismiss out of hand any tool that offered to expand his consciousness and liberate his imagination.

Paul had become friendly with the Honourable Tara Browne, the son of Oonagh Guinness and Dominick Geoffrey Edward Browne (Fourth Baron Oranmoore and Browne, member of the House of Lords since 1927), who at twenty had already been schooled at Eton, privately tutored in Paris, and married and was the father of two sons. The young Irishman had become the archetypal swinging Londoner from the aristocratic set. He didn’t need to work, owned a house in Belgravia, and was due a million-pound inheritance when he turned twenty-five, so he spent his time partying, driving fast cars, taking drugs, and dressing like a pop star. It was an indication of class barriers buckling, if not altogether crumbling, that Browne’s set of friends was defined more by wealth, looks, and available leisure time than blood, education, or family connections. Lords and ladies now mingled with the sons and daughters of cotton salesmen, factory workers, bus drivers, and coal miners, probably because the ascendant working class wanted what they had (wealth, property, manners, style) and they wanted what the ascendant working class had (drive, creative talent, fame, acclaim, and street smarts).

In the early hours of December 14, Viv Prince, the twenty-one-year-old recently deported drummer of the Pretty Things, an R & B band from London that made the Stones look well-groomed, restrained, and conventional, arrived at the Scotch with the Who’s bass player, John Entwistle. The two of them had just driven 120 miles down from Norwich, where the Who had played the Federation Club on Oak Street with Prince deputizing for Keith Moon, who was out of action for two weeks with whooping cough. At the Scotch they met Paul, John, and Tara Browne’s wife, Nicky. She invited Prince back to the couple’s mews cottage in Belgravia along with Paul, John, dancer Patrick Kerr, and a few attractive girls. John declined the offer, because he’d promised to get back to Cynthia at their home in Weybridge.

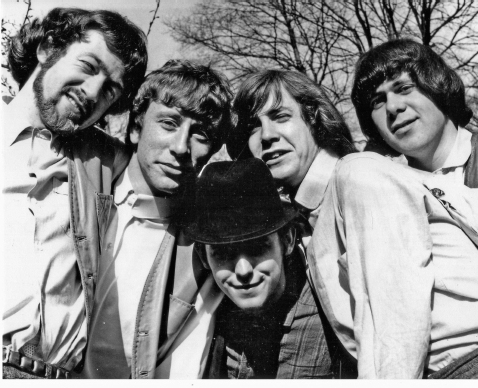

The Pretty Things: Dick Taylor, Brian Pendleton, Viv Prince, Phil May, and John Stax. Prince left the group in November 1965.

Mark St. John

When the revelers got to Eaton Row, Tara Browne was at home and suggested that they take LSD. Paul was still apprehensive. He was more in the mood for a joint and some drinks but the relief of the tour being over and the relaxing of responsibility that came with a few weeks of not having to write, record, perform, or be interviewed persuaded him that now was as good a time as ever to take the plunge. Prince had heard about LSD from his friend Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones but had never taken it and had no clear idea what the effects would be. The liquid drug was pure and was dropped onto sugar lumps that Nicky served with the tea, saying, “One lump or two?”

The trippers stayed up all night. Paul saw paisley shapes and experienced “weird things” that made him feel slightly disturbed. He looked at his shirtsleeves, and the dirt on the cuffs was so intensified that it made him feel angry. He became sensitive to every kind of stimulus—light, sound, color, even the touch of fabric. There suddenly seemed to be so much more to be gleaned from the simple things of life—depths of experience that he had so far ignored or glossed over.

Prince reacted in a very different way. Rather than becoming quiet and reflective he started drinking heavily while Paul sat leafing through a book of art. One particular image that caught Paul’s eye transfixed him for over an hour as he processed all the detail.

Paul has since wrongly dated this experience to late 1966, leading critics to believe that everything he wrote for Revolver was done before he, to adopt the language of Timothy Leary, had turned on and tuned in. Some writers have even speculated that Paul’s artistry on the LP was the result of him resisting John and George’s pressure to trip by showing them that he could outperform them without chemical assistance. But Prince’s revelation in interviews with me that this took place immediately after the Beatles’ last tour date of 1965 alters our understanding. After all, Paul has agreed with John’s statement that no one is the same after taking LSD and had called his experiences “amazing” and “deeply emotional.” In 1967 he told the Daily Mirror that his initial trip was “quite an incredible experience” that lasted for six hours; he said, “[It] opened my eyes to the fact that there is a God” and “made me a better person.”

The first of Paul’s songs recorded by the Beatles after December 1965, and therefore almost certainly the first song he composed after tripping, was “Got to Get You Into My Life.” Believing he first took LSD in late 1966, he has said in interviews (and in his book Many Years from Now) that the song was about pot, but the language of taking “a ride,” seeing “another kind of mind,” and not knowing what he “would find there” is more consistent with the language of a psychedelic trip than a marijuana high. In the song he’s talking about getting this new perspective, this new consciousness, into his life. “Far from harming me,” he told the Daily Mirror, “it helped me to see a lot more truth. I am more mature. I am less cynical. I have started to be honest with myself.” It turns out that John was right after all when he told Playboy, “It [“Got to Get You Into My Life”] actually describes his experience taking acid. I think that’s what he’s talking about. I couldn’t swear to it, but I think it was a result of that.”

The psychedelic experience had a reputation for challenging people’s basic assumptions, often leading them to believe that their lives up to that point had been based on false information or a shared fiction. Users began to question what was “real,” “normal,” or “proper” as the old standards and guideposts began to crumble. When it came to music, this manifested itself in a new attitude of openness. The dividers that separated pop from classical, Western from Eastern, and low art from high art no longer appeared relevant. Neither did the rules about the length of songs or the volume of recordings. Everything was more fluid than we had been led to believe.

But despite the changes that were taking place in the outlook of the Beatles, they were still wedded to many old show business practices. For example, they had become a part of the British Christmas experience. The season of goodwill was also the season of good business. With the Beatles had been released in late November 1963 and Beatles for Sale in December 1964. It made sound commercial sense. In both those years they’d also had the top spot on the singles chart, with “She Loves You” in 1963 and “I Feel Fine” in 1964. This year was no different in that respect. “Day Tripper” / “We Can Work It Out” topped the Christmas hit parade, while Rubber Soul was the bestselling album. However, the normal effusive jollity was at odds with their newly emerging seriousness as artists.

In 1965, they continued the tradition of making a Christmas flexi-disc recording exclusively for members of the Official Beatles Fan Club in the UK, but they were less cuddly and congratulatory. They sent up the idea of giving a message by spending the entire six minutes and twenty seconds of recording time messing about, adopting silly voices, and trying to make each other giggle. They sang a raucous version of “Auld Lang Syne,” changed the words of “Yesterday” to “Christmas Day,” and almost plowed through the Four Tops’ summer hit “It’s the Same Old Song” until George shouted out “Copyright! You can’t sing that.”

For the past two years the Beatles had headlined special Christmas shows in London that lasted almost three weeks and involved other acts managed by Brian Epstein’s company, NEMS Enterprises. For these festive spectaculars they would dress up in costumes and take part in sketches as well as sing as a group. In August 1965 it had been announced that Epstein’s artists would again be putting on a Christmas special, with Cilla Black, Gerry and the Pacemakers, and Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas, but noticeably no Beatles. Asked in a Canadian press conference whether they’d be appearing, John had said, “Ask Mr. Christmas Epstein.”

Simply put, they were butting against the boundaries of “light” entertainment. It would have been incongruous for them to dress up in capes, shawls, top hats, and cloth caps to sing recent songs such as “The Word,” “In My Life,” or “Norwegian Wood.” They didn’t want to be like previous British pop stars Cliff Richard and Tommy Steele, who’d broadened their audience by doing musicals, revues, and vaudeville-style shows that appealed to adults. This strategy may have fulfilled some of Epstein’s dreams of a life in the theatre, but it fulfilled none of theirs.

Besides, they hadn’t had a proper Christmas break since 1959. Every year since then they’d had engagements between Christmas Eve and New Year’s Day. In 1962 they’d spent fourteen days in Hamburg with only December 25 off. This year John and Ringo wanted to remain at home in Weybridge with their children (Ringo’s son, Zak Starkey, had been born on September 13), and Paul and George wanted to travel north to visit their parents.

On December 23, while they were driving together through London, George proposed to Pattie. He’d had to get Epstein’s permission beforehand, because this was still an era when the marriage of a male pop star could cost them fans and even end a career. Under existing moral codes, a married man was no longer available, and eligibility was crucial to pop stardom. As Epstein had said in his biography A Cellarful of Noise, published in 1964, “It is unwise for pop singers to marry, and so they stay single. But if they [Paul, George, and Ringo] were determined to wed, there is nothing I would wish to do to stop them.”

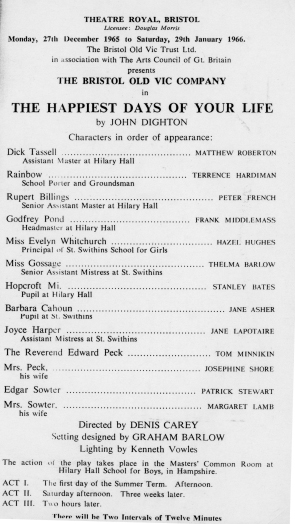

A theater program for the Bristol Old Vic production of John Dighton’s play The Happiest Days of Your Life, which featured Jane Asher.

Bristol Old Vic Company

Paul’s long-term girlfriend, Jane Asher, had arrived in Bristol to play the schoolgirl Barbara Cahoun in John Dighton’s play The Happiest Days of Your Life at the Theatre Royal, opening on December 27. Paul spent a couple of days at Rembrandt, the house on the Wirral close to Liverpool that he’d bought his father in 1964, only to find that his brother, Mike, had invited Tara Browne as a houseguest. (Although they were married for less than three years, the Brownes were on the verge of separation, and Tara was living an independent life).

On the night of Boxing Day Paul invited Browne to travel five miles to visit his cousin Bette, who lived in Higher Bebington. He had bought two new Raleigh mopeds from Camerons’ Cycles in nearby Neston to make the trip more adventurous than a normal drive. Riding along the narrow Brimstage Road, slightly high on pot, Paul was pointing out local landmarks and staring up at the bright crescent moon when his front wheel hit a stone and he was thrown off. His face hit the ground, causing an upper front left tooth to chip and forcing it through his lip. His left eyebrow was also gashed. Despite the damage and the flow of blood he continued the journey, and when they arrived Bette called up the family practitioner, Dr. “Pip” Jones, to attend to the wound.

According to Paul in the Anthology book, the doctor proceeded to try to give him stitches despite having no local anesthetic and a shaky hand. He lost the thread on the first attempt and so had to go back and resew the cut. Paul didn’t get the tooth capped until June 1966 despite Brian Epstein urging him to do so, and the gap was visible in May when the video for “Paperback Writer” was shot (despite an attempt to temporarily fill it with a piece of chewing gum).

Paul’s left eye was swollen and the eyebrow above was matted with blood. The gash on the lip looked to be at least an inch long and quite deep. News leaked out, and on December 31 the Daily Mirror ran a news story with the headline “No Fight, Says Injured Beatle.” It read: “Beatle Paul McCartney denied last night that his gashed eyebrow and cut lip were the result of a fight. He said he had fallen off his moped during his Christmas stay with his father near Liverpool.” Later a photo of his damaged face (taken by brother Mike and stolen from Paul’s home by a dishonest chauffeur) surfaced in an Italian magazine as evidence of “wild Beatle drug parties in swinging London.” (Incidentally, this disproves a story frequently told by Paul that his Sgt. Pepper–era mustache was occasioned by the need to conceal the damage from this moped accident. Over ten months separated the two events.)

Meanwhile, John’s Christmas was slightly marred by the reemergence of his father, Alf (now “Freddie”) Lennon. Singer Tom Jones’s dad had discovered him washing dishes at a restaurant in Shepperton, Surrey, and one of Jones’s management team, Tony Cartwright, had made contact with him with a view to cutting a novelty record. They managed to get a recording contract with Piccadilly (distributed by Pye), and a publishing deal with Leeds Music, and Cartwright set about composing a “song” based on Freddie’s reminiscences. The result, produced in Twickenham by John Schroeder (cowriter of Helen Shapiro’s hit “Walking Back to Happiness” and leader of the easy-listening instrumental group Sounds Orchestral), was a cloying spoken-word track titled “That’s My Life” replete with crashing waves, sobbing violins, and choral voices, over which Freddie recited platitudes about his up-and-down life. It began to get a lot of airplay because of the Lennon name.

Flushed with newfound fame, Freddie decided to pay his long-abandoned son an unannounced visit at his Weybridge home. It did not have a happy ending. “It was only the second time in my life I’d seen him,” John later revealed. “I showed him the door. I wasn’t having him in the house.”

Irritated by what he saw as his father’s exploitation of the family name, John asked Epstein to use his power to get the record suppressed. Epstein wanted Pye to withdraw it and stop the publicity campaign. Cartwright and Freddie were discreetly compensated for their potential losses (probably with funds supplied by John) to the tune of eight thousand pounds, and Pye was rewarded for its compliance in dropping the record by being given permission to use the Lennon-McCartney song “Michelle” with a group called the Overlanders that it had been recording without success since 1963. (Their version would top the UK charts in January and be the group’s only hit.)

It’s easy to forget that in 1965 rock ’n’ roll–inspired pop did not yet dominate the British charts. Of the ten bestselling singles for this year, only the Beatles’ “Help!” and “I’m Alive” by the Hollies would have qualified. The rest were comprised of folk ( “I’ll Never Find Another You” by the Seekers), ballads (“Tears” by the Liverpool comedian Ken Dodd and “Crying in the Chapel” by Elvis Presley), instrumentals (“A Walk in the Black Forest” by classically trained German pianist Horst Jankowski and “Zorba’s Dance” by Italian bouzouki player Marcello Minerbi), pop (Cliff Richard’s “The Minute You’re Gone”), and the country sound of Roger Miller’s “King of the Road.”

Half of the Top 10 albums were taken up with the soundtracks of three musicals (Mary Poppins, The Sound of Music, and My Fair Lady) and easy listening LPs by Andy Williams (Almost There) and Irish entertainer Val Doonican (The Lucky 13 Shades of Val Doonican). The other half had two recordings each by Bob Dylan (Freewheelin’ and Bringing It All Back Home) and the Beatles (Beatles for Sale and Help!) and one by the Stones (Rolling Stones No. 2).

Epstein threw an end-of-year party for his artists at his Belgravia home. After most of the guests had left, Epstein gathered the Beatles, his assistant Peter Brown, and Steve Aldo in a room at the top of the house he called the smoking room. There were gold discs on the walls, a small jukebox on top of a desk, modernistic cube seats, and, between the windows, a ship’s wheel. Brian said he had Christmas gifts from Capitol Records for the boys. He presented a small balsawood box filled with straw. When the Beatles broke it open they found several eggs, all numbered, and instructions to open them in order. Inside each egg was a clue to the identity of the real gift, and in the final one a photograph of a new-fangled piece of technology. It was called a video recorder. None of them had even heard of such an invention at the time. Early in the new year a VTR machine was delivered to each of the Beatles’ homes.

Three months later Paul talked about his recorder. “It’s the greatest little present ever,” he would say. “You just plug it into your set and you record the program straight off, just like onto a tape. You can record BBC while you’re watching ITV and show the film on your telly at one o’clock in the morning if you want to. They said we’d be the first people in England to have them.”

The Beatles’ position at the top of the record industry gave them privileged access to such advances. They traveled more widely than most of their contemporaries, listened to a greater variety of music, and were kept abreast of all the latest cultural trends. If a new club opened, they were on the invitation list. If a new style of cuisine was introduced, they’d be among the first to taste it. They were magnets for some of the most creative people in the popular arts, many of whom became part of their inner circle and benefitted from their patronage.

Paul’s Christmas gift to his fellow Beatles was an acetate disc of a radio-style show that he’d taped at home featuring music tracks by artists he thought they should take note of, linked by Paul speaking in the style of a New York DJ. “It was something crazy, something left-field just for the Beatles . . . that they could play late in the evening,” he later explained. “It was called Unforgettable and started with Nat King Cole’s ‘Unforgettable.’ It was like a magazine programme full of weird interviews, experimental music, tape loops and some tracks that I knew the others hadn’t heard.”

He was clearly hinting at the direction the Beatles might go when they reconvened in the studio, offering the sort of rich palette from which they might choose. Besides “Unforgettable” and the experimental sounds there was “Down Home Girl” by the Rolling Stones, “Don’t Be Cruel” by Elvis, Martha and the Vandellas singing “Heat Wave,” the Beach Boys with “I Get Around,” and the Peter and Gordon LP track “Someone Ain’t Right.”

Reflecting on the record selection a few months later George said, “It was a peculiar overall sound. John, Ringo and I played it and realized Paul was on to something new. Paul has done a lot in making us realize that there are a lot of electronic sounds to investigate. If we’re in the studio we don’t mentally think that this is the Beatles making a new hit LP or single. It’s just us, four blokes with some ideas, good and bad, to thrash out.”

USING JOHN’S LATER ANALOGY OF THE BEATLES BEING PART of a ship that a whole generation had climbed aboard, it’s easy to see how he saw them as being in the crow’s nest. They were high up and therefore visible to everyone, and, because of their vantage point, they were the first to spot storms and the first to spy landfall. This was the position they found themselves in at the start of 1966. The things they would see from the crow’s nest over the next twelve months would reverberate through the decades to come.