This year we’ve got more boys in the audience which is good because usually girls start the crazes.

—RINGO, 1966

It had been just over a year since George first picked up a sitar on the set of Help!, and during that period his interest in the instrument had steadily grown. He listened to ragas at home, had been taught the rudiments of playing by a teacher in London, and was now aware that a full appreciation of the music of India would only come when he’d learned the fundamentals of the Hindu religion.

At first George knew only of sitar music in general. It was David Crosby of the Byrds who in the summer of 1965 introduced him to Shankar’s music in particular. Crosby had been given a Shankar LP by Jim Dickson, manager of the Byrds, who had previously worked as a producer for World-Pacific Records in Hollywood, a small label that specialized in albums for connoisseurs of all things hip. World-Pacific recorded not only jazz musicians such as Chet Baker, Art Pepper, Gerry Mulligan, and Gil Evans but also the blues singers Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee and the eccentric monologist Lord Buckley. In 1959, the company put out the first LP Shankar recorded in America and later followed it up with two more.

Crosby played the LPs for George when the Beatles hung out with him and fellow Byrd Roger McGuinn while in Los Angeles. George told Maureen Cleave that he’d become so enamored of the music that before going to sleep at night he fantasized about what it would be like to actually be inside one of Shankar’s sitars.

Early in June 1966 he finally met his new hero. Shankar had been appearing regularly in Britain for the past decade. He had played to a full house at the Royal Festival Hall in 1958 with Alla Rakha on tabla and Prodyot Sen on tambura and five years later had been a sensation at the Edinburgh Festival. George had first seen him in London on November 7, 1965, just two weeks after recording “Norwegian Wood” and meeting the Angadis for the first time. This time Shankar was in England to appear with violinist Yehudi Menuhin at the Bath Musical Festival for an experimental concert combining the classical music of East and West.

Prior to this, on June 1, he returned to the Royal Festival Hall accompanied by Alla Rakha, and George and Pattie went to see him. The Angadis then invited the Harrisons to a meal at their house, where George met the sitarist for the first time. “I was there when they met,” says the Angadis’ daughter Chandrika. “George was a bit awkward and was resting his foot on the sitar case. Ravi Shankar said the first lesson was to take his foot off. They then both played a little in our sitting room.”

Shankar had heard of the Beatles but knew nothing of their music. “I’d vaguely heard the name of Beatles but I didn’t know what it stood for or what was their popularity,” he told me in 1982. “I hadn’t heard a single LP or song. But it was nice to see George’s humility and to know that he wanted to learn. I said he should come to India, and eventually he did.”

When journalists asked him what he thought about the Beatles’ use of Indian instruments, he would only say that if they were serious about it, they should make sure they learned to play them properly. This had been interpreted as a criticism, but he had meant only that anyone attempting to master the sitar needed to invest the necessary time. It wasn’t an instrument to be toyed with.

George was aware of his inadequacies. He’d only had a handful of lessons, from a student of one of Shankar’s students. He was now embarrassed at the rudimentary nature of his playing on “Norwegian Wood” but had an appetite to learn more. He was willing to put aside time for practice and also wanted to learn more about Indian culture and beliefs.

Shankar found him a “sweet, straightforward young man” and was impressed by his questions. He told him that learning the sitar was like learning classical music on the violin or cello. It wasn’t simply a matter of how to hold the instrument and play a few chords. It wasn’t as easy as knowing enough about a guitar to master a few rock ’n’ roll songs.

“It’s not only the technical mastery of the sitar,” said Shankar. “You have to learn the whole complex system of music properly and get deeply into it. Moreover, it’s not just fixed pieces that you play—there is improvisation. And those improvisations are not just ‘letting yourself go,’ as in jazz—you have to adhere to the discipline of the ragas and the talas without any notation in front of you. Being an oral tradition, it takes more years.”

George was in awe of Shankar. As a Beatle he’d met many famous, powerful, and influential people, but he was aware of depths of creativity and spirituality in this musician that he’d never come across before. “He was the first person who impressed me in a way that was beyond just being a famous celebrity,” he later said. “Ravi was my link to the Vedic world. Ravi plugged me into the whole of reality. Elvis impressed me when I was a kid, and impressed me when I met him . . . but you couldn’t later on go round to him and say, ‘Elvis. What’s happening with the universe?’”

More than anything, George wanted Shankar to become his mentor. Shankar must have been aware of this, which is why he stressed the toil and commitment required. He asked George if he could give “time and total energy” to work hard on it. Mindful of the Beatles’ calendar, George could only say he would try his best.

During this stay in England Shankar recorded the album West Meets East with Yehudi Menuhin (at EMI), visited George and Pattie at home in Esher, and gave George lessons at the South Kensington apartment of folksinger and artist Rory McEwen. He showed George how to hold the sitar and told him the traditional names of the various notes, and George made a promise to spend extended time with him in India as soon as he was free of Beatles commitments.

Shankar was a cultured man who, besides having an extensive knowledge of his own country’s culture, had been exposed to the best of Western classical music, dance, film, painting, and theatre. He was also open to cross-fertilization that didn’t compromise the purity of sitar music. Yet despite mixing with the bohemian and avant-garde of Europe and America, Shankar didn’t approve of drug use. He resisted the overtures of those who thought he’d be an even greater musician if he took LSD and complained about cannabis use when his UK promoter, Basil Douglas, booked him into folk clubs. It particularly irked him that some longhairs would trip out at his concerts as if there was some connection between Eastern classical music and hallucinogens. He found this disrespectful to the music.

The Beatles helped make sitar music voguish in pop circles, but it had already been popular among Beats in the 1950s and was now with hippies. Allen Ginsberg had traveled to India in 1962 and came back chanting the Hare Krishna mantra. Hip musicians like folkie Davey Graham incorporated Eastern scales into their guitar playing. The London-based Indian violinist John Mayer had formed a group called Indo-Jazz Fusions with Jamaican sax player Joe Harriott. The “hippie trail” favored by seekers of enlightenment from North America and Europe went overland to India. There were hippie hangouts in places like Rishikesh, Goa, Puri, and Benares (now Varanasi).

The week that Shankar arrived in London the Rolling Stones were poised to take the top spot on the singles charts with “Paint It Black,” on which Brian Jones played sitar, and the Yardbirds had entered the charts with “Over Under Sideways Down,” a track on which Jeff Beck used eastern modes of tuning for his guitar. Melody Maker had recently run a feature titled “How About a Tune on the Old Sitar?” that investigated the trend with a lot of information gleaned from guitarist (and sitar owner) Jimmy Page.

On June 8, Shankar played a short raga on BBC TV’s new weekly pop magazine show A Whole Scene Going and then answered questions from studio guests, including members of the Yardbirds. Singer Keith Relf asked him what he thought of English and American pop groups using sitars. “Well, I’m afraid this sudden interest might go away suddenly,” Shankar told him. “But on the other hand it will make me very happy if I see that some people take true interest and learn properly because after playing the sitar for thirty-six years I have seen that one has to give some time to it.” Someone else asked how long he thought the “gimmick” would last. “It has always been the case with pop that new sounds come and go,” he said. “It could be the Japanese koto tomorrow.”

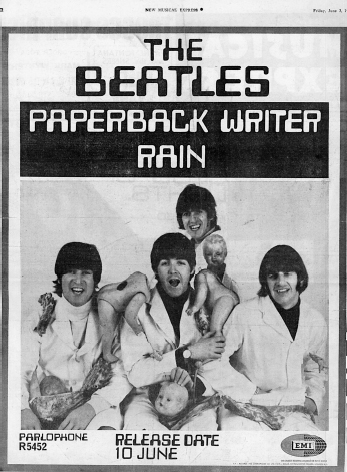

The same day that George went to the Ravi Shankar concert at the Royal Festival Hall, NME ran a back page ad for “Paperback Writer” and “Rain” that used a black-and-white copy of Robert Whitaker’s “butcher” photographs. There was no clue as to what connection—if any—there was between the image of the Beatles with huge cuts of meat and the songs. The only information was that the single was to be released on June 10. On June 11 Disc and Music Echo used a color photo from the same session on its front cover under the headline “Beatles; What a Carve-Up!”

Meanwhile, in America, the image was being used for Yesterday and Today, the filler LP with tracks from Help!, Rubber Soul, and the current sessions that was being prepared for June 15 release. Capitol’s art director George Osaki liked the butcher shot, and so the sleeves went into production for a run of a million copies for the mono format and two hundred thousand for the stereo. Sixty thousand advance copies were shipped to newspapers, magazines, radio, TV, and Capitol Records’ promotional teams, who in turn were presenting the new product to key retailers. Alan Livingston, then president of Capitol, had blanched when he first saw the chosen image and called Brian Epstein, but was told that the Beatles were insistent that it be used.

A UK advertisement for the single “Paperback Writer” on the back cover of NME, June 3, 1966.

Steve Turner Collection

Then the retailers refused to handle it. They found it brutal and offensive, even though the bloodstains on the Beatles’ coats had been airbrushed out. Livingston got back to Epstein, who, after pressure, allowed Capitol to use an earlier photo by Whitaker taken at the NEMS office showing the group posed inoffensively around a steamer trunk. By now so many copies of the album with the butcher photograph had been pressed that the only way of salvaging the existing copies was to keep the vinyl but destroy the cardboard and wait for new covers to be printed. Operation Retrieve—which would cost Capitol over two hundred thousand dollars—started on June 10 with the pressing plants recalling all copies. Workers in New York spent a weekend stripping ninety thousand discs out of their sleeves. Queens Litho, where printing took place, destroyed a hundred thousand unused copies. At the Scranton and Los Angeles facilities they found a way of cutting costs by pasting the newly approved image over the old one. In future years when careful collectors were able to steam off the replacement image, these preserved “butcher covers” would become valuable items on the pop memorabilia market.

A release was put out by Capitol press officer Ron Tepper telling reviewers about the new cover and asking them to disregard their “butcher” copies (and, if possible, return them). Livingston was quoted as saying, “The original cover, created in England, was intended as ‘pop art’ satire. However, a sampling of public opinion in the United States indicates that the cover design is subject to misinterpretation. For this reason, and to avoid any possible controversy or undeserved harm to the Beatles’ image or reputation, Capitol has chosen to withdraw the LP and substitute a more generally acceptable design.”

But for the Beatles the only LP occupying their attention was the one they were making. George’s “I Want to Tell You” was recorded on June 2, Paul’s vocal was added to “Eleanor Rigby” on the sixth, and on the eighth they started on the newly written “Good Day Sunshine,” a typically buoyant and optimistic song written mainly by Paul on one of his writing visits to Weybridge. Although ostensibly about the joys of good weather, it had all the hallmarks of being as much about the benefits of sunlight as “I’m Only Sleeping” is about restorative rest. In the context of June 1966 it sounded like a song about being mellowed out on dope and the resultant feeling of well-being.

An immediate source of musical inspiration was “Daydream” by the Lovin’ Spoonful, then at No. 15 on the Top 20, a carefree song about walking in the sun and falling about on a new-mown lawn. Paul, John, and George had seen the Lovin’ Spoonful perform at the Marquee Club in London seven weeks earlier and enjoyed their gentle electrified folk. Another inspiration could have been “Sunny Afternoon” by the Kinks, which had just charted.

The next song that Paul wrote at John’s house was “Here, There and Everywhere,” the recording of which started on June 14. It was in part influenced by the recent exposure to Pet Sounds, as Paul explained to American writer David Leaf in 1990.

It’s actually just the introduction that’s influenced [by the Beach Boys]. John and I used to be interested in what the old fashioned writers used to call the verse, which we nowadays would call the intro . . . this whole preamble to a song, and I wanted to have one of those on the front of “Here, There and Everywhere.” John and I were quite into those from the old-fashioned songs that used to have them, and in putting that [sings “To lead a better life”] on the front of “Here, There and Everywhere,” we were doing harmonies, and the inspiration for that was the Beach Boys. We had that in our minds during the introduction to “Here, There and Everywhere.”

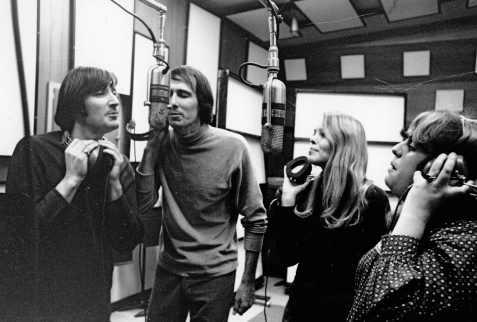

The day after starting “Here, There and Everywhere” John went to Dolly’s in the evening with Mick Jagger and his girlfriend, Chrissie Shrimpton. Later the trio was joined by John Phillips and Denny Doherty from the Mamas and the Papas, who were in London to promote their new single “Monday Monday.” Like the Byrds, the members of the Mamas and the Papas had been part of the American folk scene until the music of the Beatles transformed their vision. As a group they felt the kinship between folk melodies and the tunes from Liverpool and switched to a louder sound and electric guitars, scoring a huge hit with “California Dreamin’.”

The Mamas and the Papas: Denny Doherty, John Phillips, Michelle Phillips, Cass Elliot.

TJL Productions

They were identified with the emerging counterculture that had developed out of California’s 1950s hipster culture. Beat generation writers, comedians from the satire boom, civil rights, pot, LSD, and the peace movement had affected them. The Papas wore facial hair and suede boots. The Mamas wore kaftans and skinny jeans. (A year later Phillips would cowrite “San Francisco [Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair]” with his friend Scott McKenzie, who would go on to have a huge international hit with the song. It was designed to publicize the imminent Monterey International Pop Music Festival, the first of the iconic open-air music festivals.)

Phillips asked John where he and Doherty could get marijuana. John made a call, and half an hour later Paul came down from St John’s Wood with a small bag of grass. They spoke openly to Phillips about being introduced to the drug Eskatrol while in America in 1964. This was an amphetamine-based weight-loss drug manufactured by SmithKline and French in America but unavailable in the UK. John claimed that he and Paul had been writing songs while high on it ever since. Phillips admitted to the same practice.

Cass Elliot had stayed behind in the Montagu Square apartment that the group was renting, but, knowing that she was such a huge Lennon fan, Phillips invited John and Paul back to meet her when they left the club in the early hours of June 16. When they reached the apartment, Cass was asleep and was awoken by John leaning over and kissing her gently on the cheek. She sat up, got out of bed, and danced around the room with him out of sheer joy.

John and Paul stayed up all night listening to music, playing songs on the apartment’s out-of-tune grand piano, and smoking dope. They didn’t leave until eight in the morning. “[John] was charming, courteous and intelligent,” Cass told a journalist later that day. “He was witty, amusing and entertaining. It was like everything had been motivating towards that meeting last week.” She invited the Beatles to stay at her home next time they were in LA.

The final track of the album was John’s “She Said She Said,” recorded on June 21. It was at the last stage that the group realized that the record was much too short. The last three LPs were on average around thirty-four minutes in length. This LP, so far, ran to only just over thirty-two minutes. “Paperback Writer” and “Rain” could have added bulk, but including them went against their principle of not adding previously released singles to their UK LPs. Five days previously John had remarked to a journalist, “I’ve got something going [for the LP’s final number]. About three lines so far.”

He was referring to “She Said She Said,” a song based on John’s 1965 LSD trip in the company of George, Roger McGuinn, David Crosby, and actor Peter Fonda at the Beatles’ rented home in Benedict Canyon, Los Angeles. Both John and George were hoping for a better experience than they’d had with the dentist in London now that they knew more about the drug and were taking it voluntarily. However, early on in his trip George developed a fear that he was dying, and Fonda attempted to calm him down. He did so by recounting the story of how he had accidentally shot himself in the stomach as a ten-year-old and how his heart had stopped three times while in the operating room because of the severe loss of blood. He drove home what he hoped would be a reassuring message by saying, “It’s all right, George. I know what it’s like to be dead.” John overheard the remarks and became upset. In his altered state he didn’t want to hear about guns, bullets, blood, and death. “You’re making me feel I’ve never been born,” he told Fonda.

This bizarre drug-induced conversation became the foundation of a song that John put to the side as not going anywhere but then salvaged by joining to another abandoned lyric exploring the joys of childhood innocence. “When I was a boy,” he wrote, “everything was right.” This wasn’t just nostalgia. He believed the mind of a child to be more aware and less corrupted than that of an adult. He also claimed to have had uninvited experiences of rapture at an early age that he hadn’t understood at the time but which he later recognized in the writings of men like Thomas De Quincey (Confessions of an English Opium-Eater) and Lewis Carroll (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland). Through poetry anthologies that Aunt Mimi collected he may have been aware of the popular Victorian poem “I Remember, I Remember” by the English poet Thomas Hood, which recounted pleasant childhood memories before concluding:

It was a childish ignorance

But now ’tis little joy

To know I’m farther off from Heaven

Than when I was a boy.

The splicing of separate unfinished songs in this way was a new departure that echoed the practice of electronic composers who connected material from previously unrelated sources to create new work. It was something the Beatles would pursue in later songs such as “Baby You’re a Rich Man,” “A Day in the Life,” “Happiness Is a Warm Gun,” and the medley on Abbey Road, which often blended a fragment of a song started by John with a fragment of something started by Paul.

“She Said She Said” was recorded and mixed in nine hours, the only song on the LP to be completed in a single session. It appears that George played the bass after Paul stormed out following an argument with John. “I think it was one of the only Beatle records I never played on,” said Paul. “I think we’d had a barney [a noisy quarrel] or something.” John saw the incident as giving him the opportunity to complete the track in the way he saw fit without Paul’s suggestions. In January 1969, when recording the Let It Be LP, John was again at loggerheads with Paul, who he accused of taking over the project. In one revealing exchange, captured by the film team covering the whole event on their soundtrack, John said that he’d found that the only way to record something to his satisfaction was to do it alone. Speaking to Paul, he then referred back to this session in 1966, saying, “The only regret I have about past numbers is because I’ve allowed you to take it somewhere I didn’t want it to go. Then my only chance was to let George take over because I knew he’d take it. Like on ‘She Said She Said.’”

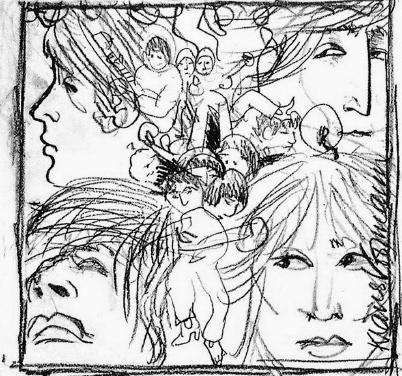

During the recent recording musician and artist Klaus Voormann had been preparing an album cover, the Beatles having rejected a montage of black-and-white images put together by Robert Freeman, who’d done all their UK LP covers since With the Beatles in 1963. They were looking for something different and more in keeping with their new music. Voormann had met the Beatles in Hamburg in 1960 when he was studying to be a commercial artist and they were struggling musicians playing in clubs. He, his girlfriend Astrid Kirchherr, and photographer Jurgen Vollmer were an important link between the Beatles and European culture. Up to this point they had mostly been influenced by British and American culture, but now, through recommendations from these young “exis” (existentialists), they connected with postwar French and German photography, films, art, clothing, and literature. The Beatles copied the long swept-forward hairstyle of Vollmer and Voormann and also their black turtlenecks, and out of this developed the early Beatles style as captured on the cover of their second UK LP, With the Beatles.

Voormann had left Germany for Britain, where he played bass in Paddy, Klaus, and Gibson alongside two Liverpool musicians (Paddy Chambers and Gibson Kemp) he’d met in Hamburg. Initially managed by Tony Stratton-Smith (who later founded the independent record label Charisma), the trio then became part of Epstein’s roster. When John approached Voormann about the cover design, he had just quit the group and was about to replace Jack Bruce in Manfred Mann. (Bruce was forming Cream with drummer Ginger Baker and guitarist Eric Clapton.) Because of this transition he almost passed on the offer but eventually accepted.

Voormann went to EMI Studios, where the Beatles played him some already mixed tracks, including “Tomorrow Never Knows,” and he was so impressed with the direction they were going in that he determined to produce a design that was as adventurous pictorially as this track was musically. All he asked of them was that they collect some old images of themselves that he could incorporate into his artwork.

While Voormann worked on his preliminary drawings John, Paul, and Pete Shotton trawled through a pile of photographs, the majority of which happened to be images from 1964 and 1965 by the recently rejected Robert Freeman, and snipped out images that they then glued onto a paper sheet. Voormann transferred these pictures to four heads he had drawn of the Beatles so that the photos appeared to be emerging from the heads and crawling out of the hair.

Voormann’s style of black-ink line drawing that contrasted fine detail (the strands of hair) with white space (the faces) was strongly influenced by the Victorian artist Aubrey Beardsley, who was associated with fin de siècle decadence, aestheticism, and art nouveau. King’s Road boutique designers were enamored of Beardsley’s erotic illustrations and doomed romanticism (he died at twenty-five), and the most comprehensive exhibition of his work ever mounted opened on May 20 at the Victoria and Albert Museum, where it would run for four months. (A portrait of Beardsley would turn up in 1967 on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and Paul collected some of his original work.)

One of Klaus Voormann’s preliminary sketches for what would become the cover art of Revolver.

Klaus Voormann

It was very different than any other LP cover on the pop market at the time. The Beatles didn’t look pretty, and there were virtually no smiles. The eyes were expressionless. The name of the group appeared on the spine and the back, but not on the front. Like Goya’s eighteenth-century illustration The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, it was as though John, Paul, George, and Ringo were in another state of consciousness that was causing these earlier versions of them to escape. (Peter Blake’s cover art for Sgt. Pepper would also contrast old and new Beatles by standing them next to wax models of themselves as they were in 1964 from Madame Tussauds.)

Voormann took the completed art to a meeting at EMI with George Martin and Judy Lockhart-Smith (now engaged to Martin following his divorce from his first wife in February), Brian Epstein, and the four Beatles. He stood the page on top of a steel filing cabinet and awaited their response. Initially there was a silence that for a moment he feared was a mixture of shock and disapproval, but then the plaudits started coming. They all felt it was a perfect visual complement to the music, even though he hadn’t been given a title to work with. Brian Epstein even cried, perhaps out of relief after the debacle of the “butcher” cover. “Klaus, this is exactly what we needed,” he said. “I was worried that this whole thing might not work. But now I know that his cover, this LP, will work. Thank you.”

Over the past few months Epstein had been preoccupied not only with ensuring that the single and LP were prepared and on schedule but also with arranging the concerts in Germany, Japan, the Philippines, and America (the Philippines having being added at a late stage). On June 16 the Beatles had the necessary inoculations for travel and then performed on BBC TV’s Top of the Pops in what would be their last live TV appearance other than the satellite linkup for “All You Need Is Love” in 1967.

During a break at the BBC Television Centre in White City, London, NME’s Alan Smith had a chance to interview Paul, albeit in a restroom, the only place where they could be sure to be safe from the fans. He spoke about the new LP: “I suppose there are some who won’t like it,” he admitted, “but if we tried to please everyone we’d never get started. As it is, we try to be as varied as possible.”

“There’s no real weird stuff. . . . Anyway, I’ve stopped regarding things as way-out any more. There’ll always be people around like that Andy Warhol in the States, the bloke who makes great long films of people just sleeping. Nothing is weird any more. We sit down and write, or go into the recording studios, and we just see what comes up. I’m learning all the time. You do, if you keep your eyes open. I find life is an education.”

He then spoke about “Tomorrow Never Knows,” claiming responsibility for the “electronic effects.” “We did it because I, for one, am sick of doing sounds that people can claim to have heard before. Anyway, we played it to the Stones and The Who, and they visibly sat up and were interested. We also played it to Cilla [Black]—who just laughed!”

The same day, in the same place, Alan Walsh from Melody Maker managed to corner George, who told Walsh how much he’d been changing since 1964. “I’ve increasingly become aware that there are other things in life than being a Beatle,” he said. “I’m not fed up at being a Beatle, far from it, but I am fed up with all the trivial things that go with it. For instance, at one time you could never go to the pictures or out for a meal without some idiot taking a photograph of you. I suppose I have consciously been backing away from this side of Beatle life. In fact, it wouldn’t worry me at all if nobody ever took my photograph again.”

He wanted to talk about music and the progress they were making.

In the Beatles, we’re fortunate because each of us has something different going. I’ve been going for the Indian thing in a big way, John and Paul have their own thing going, and there are also things Ringo likes. Paul likes classical music—at least, I think he does from what I’ve been able to make out watching him—and he contributes the things like “Yesterday,” and “Michelle,” while John does things like “Norwegian Wood.” This means there’s no single influence, such as there is with Brian Wilson in the Beach Boys. We have a wide range of things available to us, which makes us so exciting.

Although they’d appeared on Top of the Pops before, their performances had always been prerecorded. This was the first, and last, time that they would appear in person on the TV show that was integral to the life of every British pop fan, with its latest news of what was climbing or slipping on the charts, what was tipped for the top, and, most of all, what had reached No. 1. The Beatles, wearing dark suits over open-necked white shirts, mimed along to “Paperback Writer” and “Rain.” Their co-performers on the show were Gene Pitney, Herman’s Hermits, and the Hollies. Previous appearances by the Yardbirds (“Over Under Sideways Down”), the Kinks (“Sunny Afternoon”), and Cilla Black (“Don’t Answer Me”) were replayed, along with a video the Beach Boys had made to accompany “Sloop John B” and a troupe called the Gojos dancing to Frank Sinatra’s latest hit, “Strangers in the Night.” The hosts were Samantha Juste, who later married Monkees drummer Mickey Dolenz, and DJ Pete Murray.

It was a shock when “Paperback Writer” didn’t immediately take the top spot on the charts. It was held off by Sinatra’s single and had to wait until the following week to make it to No. 1. This would have been a supreme accomplishment for anyone else, but the Beatles weren’t expected to have to wait, and No. 2 on the charts wasn’t good enough. Again questions were being asked in the press. Was their immersion in more serious art forms taking the pop out of their music? Had “Paperback Writer” been a slower seller because it wasn’t about love? Patrick Doncaster, the show business correspondent for the Daily Mirror, commented that neither “Paperback Writer” nor “Rain” had “any romance about them. Gone, gone, gone are the days of luv, luv, luv.” When Doncaster quizzed Paul about the new direction, Paul stuck to his convictions. “It’s not our best single by any means,” he said, “but we’re very satisfied with it. We are experimenting all the time with our songs. We cannot stay in the same rut. We have got to move forward. . . . Our new LP is going to shock a lot of people.”

June 17 was the day that Paul closed the deal on the 183-acre High Park Farm on the Scottish peninsula of Kintyre that would become his beloved getaway when times got tough. He had bought it on the recommendation of his accountant, who told him that he needed to invest some of his wealth. It was remote, unmodernized, and exposed to the winds and rains that whipped across the Irish Sea. He’d always been a nature lover, and so he liked the fact that the surrounding fields had sheep and deer, while the hedgerows and trees were home to thirty-seven different types of birds. The next year, when visiting with Jane for a weekend, he told a photographer who tracked them down, “This is one of the quietest places on earth. The scenery is wonderful. We can relax and get away from it all.”

On June 21, the group attended a “pre-opening celebration” at the latest London discotheque, Sibylla’s, on Swallow Street, close to Piccadilly Circus, in which George had a 10 percent shareholder stake (he hadn’t invested money but was given the shares because of the obvious publicity value he brought to the venture). Other shareholders included photographer and advertising man Terry Howard, copywriter Kevin Macdonald (a grandnephew of Daily Mail owner Lord Northcliffe), DJ Alan Freeman, champion National Hunt jockey Sir William Pigott-Brown, and property developer Bruce Higham. The interiors were created by soon-to-be fashionable designer David Mlinaric, and the guest list, which also included Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Julie Christie, Michael Caine, David Bailey, Michael Rainey, Mary Quant, Celia Hammond, Jacqueline Bissett, John Barry, Jane Birkin, and Jane Ormsby-Gore, epitomized the cool scene so perfectly that it was later published in Queen magazine under the heading “How Many Swinging Londoners Do You Know?”

There were also connections with the darker side of London’s nightlife. The club’s manager, Laurie O’Leary, was a friend of the notorious Kray twins, Reggie and Ronnie (he’d previously run their club Esmerelda’s in Knightsbridge for them), and groups hired to play at Sibylla’s were contracted by an agency run by their elder brother, Charlie Kray. All three Krays ran a gang based in London’s East End that earned money through robberies, hijackings, and protection rackets, but, partly because of their connections with show business, they were glamorized and were regarded as being as much a part of the swinging scene as pop stars, models, and the aristocracy. They were photographed by David Bailey and feted by members of the House of Lords, and they socialized with movie stars and stage entertainers. In his autobiography, Ronnie Kray, eventually sent away for killing fellow gangster George Cornell at the Blind Beggar pub in March 1966, wrote, “They were the best years of our lives. They called them the swinging sixties. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones were rulers of pop, Carnaby Street ruled the fashion world . . . and me and my brother ruled London. We were fucking untouchable.”

Thus it was that gangland characters and gay hustlers mingled in the new “classless” society with pop stars, photographers, disc jockeys, wealthy aristocrats, and ruthless landlords. Sibylla’s was named after former debutante Sibylla Edmonstone, raised at Duntreath Castle in Scotland as the daughter of a baronet, yet Kray associate Freddie Foreman could say of it in his autobiography, Brown Bread Fred, “Although [Sibylla’s] was an exclusive club with a restricted membership of only 800, I was always welcome at the club.”

When shareholder Kevin Macdonald was interviewed by Jonathan Aitken in 1966 for his book The New Meteors, he said,

Sibylla’s is the meeting ground for the new aristocracy of Britain, and by the new aristocracy I mean the current young meritocracy of style, taste and sensitivity. We’ve got everyone here: the top creative people; the top exporters; the top brains; the top artists; the top social people. And we’ve got the best of the PYPs [pretty young people]. We’re completely classless. We are completely integrated. We dig the spades man. . . . We’ve married up the hairy brigade—that’s the East End kids like photographers and artists—with the smooth brigade, the debs, the aristos, the Guards officers. The result is just fantastic. It’s the greatest, happiest, most swinging ball of the century, and I started it!

Writing in the Daily Express earlier in the year, the Scottish aristocrat Robin Douglas-Home had argued that swinging Londoners were rapidly becoming Britain’s new cultural elite. “The ‘privileged class’ today consists of actors, pop singers, hairdressers, and models,” he wrote. “Look what happens when Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor arrive at London Airport or when the Beatles leave London airport. They get special treatment of the kind that would never be granted to, for instance, the Duke of Marlborough, whose main privilege nowadays is that he has to pay more taxes than most. If a 14th Earl with a grouse moor and George Harrison with Patti [sic] Boyd walked together into a restaurant and there was only one table left, who would be given the table? Well—if the head waiter had any sense—obviously George and Patti.”

The morning after the party at Sibylla’s, the Beatles took an 11:05 BEA flight from London to Munich on the first leg of their world tour. It was the first time they’d played in the country since 1963 and their first tour date since Cardiff in December 1965. The tour was organized by Karl Buchmann Productions in conjunction with the German teenage magazine Bravo. Because the Beatles didn’t want to appear in massive arenas, they were booked into venues with capacities of fewer than eight thousand seats, and it was accepted from the start that Bravo would be subsidizing the tour rather than making money, because the income from 34,200 tickets (the total sold) didn’t cover the cost of mounting the tour.

After arriving at just before 1:00 p.m. the Beatles were picked up in a white Mercedes and taken to the 125-year-old Hotel Bayerischer Hof on Promenadeplatz, where in their fifth-floor suite they immediately set about thinking of a title for the new LP with Brian Epstein, Neil Aspinall, Mal Evans, and Tony Barrow. The tracks were played on a small reel-to-reel tape recorder that George had brought with him. “Magic Circle” suggested Paul. “Four Sides to the Circle” responded John. Ringo humorously suggested “After Geography,” a play on the Stones’ recent LP title Aftermath. Nothing was decided.

At 4:10 on their way down to the hotel’s nightclub the elevator stuck between floors, making them late for their press conference, which didn’t start until 4:20. Journalists treated them as if they were still children. Did they like Munich? Did they speak German? What sport would they choose if they could participate in the recently announced 1972 Olympic Games in Munich?

The two concerts, held the next day at the 3,500-seat Circus Krone at 5:15 and 9:00, consisted of eleven songs, none of them from the forthcoming LP. The only difference from the set list of their winter tour of the UK in 1965 was the replacing of “Act Naturally” with “I Wanna Be Your Man,” “We Can Work It Out” with “Paperback Writer,” and “Help!” with Chuck Berry’s “Rock and Roll Music.” Instead of dark suits over black turtlenecks they were now all wearing the Hung On You bottle-green suits with silk faced lapels and high-collared crepe shirts in lime and yellow. Their supporting acts were the German group the Rattles, Peter and Gordon, and London R & B group Cliff Bennett and the Rebel Rousers.

Their performances weren’t great. They were underrehearsed and often out of tune, and occasionally forgot the lyrics. Not that any of this mattered, because they were competing against a wall of sound that was louder than anything they could generate. What was important to the fans wasn’t what they sang, or how they sang it, but that they were there in the flesh. The opening chords of each song announced what was about to be played, and then the screaming started and lasted until the song ended.

The difference on this tour was that the ferocity of the fans was met with equal ferocity from the police. For the first time the Beatles and their entourage witnessed fans being manhandled and beaten by men in trench coats carrying long clubs. They didn’t like what they saw but were powerless to intervene.

Sean O’Mahony, publisher and editor (as “Johnny Dean”) of the Beatles Book Monthly, asked Paul if he felt that playing so many old songs rather than the ones they’d just completed was a retrograde step. “They’re a step back in time,” he agreed. “As for performing [the new material] on stage—I don’t think our audience would like it. That, of course, depends on where we’re playing. Germany cried out for the old hits.” They were still playing primarily old hits and tracks from With the Beatles, Beatles For Sale, and Help! There was one track (“Nowhere Man”) from Rubber Soul. “I can’t play any of Rubber Soul,” John explained. “It’s so unrehearsed. The only time I played any of the numbers on it was when I recorded it. I forget about songs. They’re only valid for a certain time.”

After the two shows there was a party to which a number of high-class escorts from the area were invited. Sue Mautner, from the Beatles Book Monthly, was the only journalist present. The girls seemed so beautiful to her that she assumed they were models, and she couldn’t understand why they all disappeared at midnight. When she asked George, he just laughed. “The hotel doesn’t allow those sorts of girls in guests’ rooms after midnight,” he explained to her.

On June 25 the Beatles were transported the four hundred miles from Munich to Essen in northern Germany by a chartered train with carriages that had been designed for use by visiting heads of state (including Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip in May 1965). Each Beatle had his own compartment with a marble bath and bed, and there was a central dining carriage offering such lunchtime delicacies as clear oxtail soup with vintage sherry, artichokes with Hollandaise sauce, and medallions of Hawaiian veal.

At Essen they played two concerts at the Grugahalle, between which they conducted a press conference. Again the questions were banal. What did they think of Essen? What did they think of the noise made by the crowds at beat music concerts? Did they play for love or money? What did they think of the Rhine River? The Beatles were clearly disgruntled with not being asked anything serious or anything about their musical or lyrical contributions. No one asked about the LP they’d just finished.

Q: What do you think about people who have written about you? Do you think they have intelligence or not?

GEORGE: We don’t think . . .

JOHN: Some are intelligent, some are stupid. Some are silly, some are stupid. [It’s] the same in any crowd. They’re not all the same. Ein is clever. Ein is soft . . . [Laughter]

Q: What do you think of the questions you are getting asked here?

JOHN: They’re a bit stupid. [Laughter, applause, end of press conference]

The concerts were memorable for the riotous behavior of the fans and the militaristic way in which the security police dealt with them. “Essen was frightening,” recalls Sue Mautner. “Peter Brown saved me from being trampled to death. There was a stampede like I’d never seen. The police were like Nazis with long greatcoats and they used tear gas and vicious guard dogs. It was awful. People were trying to get away from them. They left their shoes behind in the panic.”

After the second concert a limousine took the Beatles straight from the concert hall to the station, where they reboarded the train, which was now bound for Hamburg, an overnight journey of 230 miles. John was reading A Thurber Carnival, a collection of humorous pieces from the New Yorker by James Thurber, and nursing a sore throat by drinking lemon tea and sucking lozenges. Paul came up with another suggestion for the album title—“Pendulum”—and then, when no one responded positively to this, facetiously suggested “Rock ’n’ Roll Hits of ’66.”

Their arrival in Hamburg was highly anticipated. It was the German audiences in Hamburg who’d spotted the group’s potential and had nurtured their development from callow adolescent hobbyists to battle-hardened professionals. It was the Hamburg audiences’ demand to be entertained, calmed down, excited, amused, and surprised that had forced John, Paul, George, Stuart Sutcliffe, and Pete Best to learn how to orchestrate a set and taught them what worked from a vast catalogue of rock ’n’ roll standards, show tunes, ballads, and, eventually, their own self-written songs.

They arrived at Hamburg’s main rail station at 6:00 a.m. on June 26 and were given a police escort to the Hotel Schloss in Tremsbüttel, a converted nineteenth-century palace eighteen miles north of the city. Once settled in, the group rested until their 2:45 pickup, again with a police escort, which got them to the Ernst-Merck-Halle at 3:45.

There were many old friends in the audience for the shows: Astrid Kirchherr, Stuart Sutcliffe’s old girlfriend, who’d taken the first artistic portraits of the Beatles, with her boyfriend, Gibson Kemp; Bettina “Betty” Derlien, a waitress from the Star Club who’d been particularly close to John; Katharina “Kathia” Berger, an artist who met them at the Top Ten Club; the actress Evelyn Hamann; and Bert Kaempfert, the composer, producer, and arranger who’d first recorded the Beatles as the backing group for guitarist/vocalist Tony Sheridan in Hamburg in 1961. Coincidentally, Kaempfert was also the composer of “Strangers in the Night,” the Frank Sinatra hit that had prevented “Paperback Writer” going straight to No. 1 on the UK charts. John greeted Kaempfert by singing him the opening lines of the Sinatra song.

Most of these old friends hadn’t seen the Beatles perform since their last Hamburg club dates. Now they were on stage before 5,600 screaming fans with riot police on hand. Kirchherr handed John a collection of the letters he’d written to Stuart Sutcliffe after the Beatles returned to England. “A lot of ghosts materialised out of the woodwork,” said George of the date, which seemed to stir as many bad memories for the Beatles as good ones. “There were people you didn’t necessarily want to see again who had been your best friend one drunken Preludin [stimulant tablets] night back in 1960.”

Between the two shows there was the last German press conference, one that clearly frustrated the group because of its banality.

Q: What do you think about your fans in Germany?

RINGO: They’re good, you know. They’re the same as everywhere else, only there’s more boys in Germany.

Q: Do you believe your book [A Spaniard in the Works] is literature, or do you believe just for fun?

JOHN: It’s both, isn’t it? I mean, it doesn’t have to be one or the other.

Q: Do you think it’s GREAT literature like James Joyce?

JOHN: It’s nothing to do with James Joyce, you know. I mean, you’ve been reading the wrong books and magazines. It’s nothing to do with it. It’s just a book, you know.

Q: Would Paul make music to go with your books?

JOHN: Well, I’ll make it meself, if anybody’s gonna do it.

PAUL: You’re not really writing songs.

Q: What do you dream of when you sleep?

PAUL: The same as anyone dreams of. Standing in my underpants.

JOHN: What do you think we are? What do you dream of? [Under his breath] Fucking hell!

PAUL: We dream about the same things as everyone.

Q: Ringo, what do you dream?

RINGO: I just dream of everything like you do, you know. It’s all the same.

JOHN: We’re only the same as you, man, only we’re rich. [Laughter]

While in the dressing room at Hamburg between shows a telegram was delivered to the Beatles that said PLEASE DO NOT FLY TO TOKYO. YOUR CAREER IS IN DANGER. It wasn’t signed. Was it a friendly warning from someone who knew of a plot or a sinister threat from a plotter? Paul and Ringo shrugged it off. They were used to the behavior of cranks. But George took it more seriously. “It makes you think,” he said after reading it. “We’ve got a lot of enemies as well as friends.”

After the second show there had been a plan for the Beatles to visit their old haunts in the St. Pauli district, but it was deemed too risky in light of the fan mania in Germany. There was no way they could go alone without protection, and yet if they’d gone with security guards, it would have only drawn more attention. In the end, Sue Mautner went to investigate with Daily Mirror journalist Don Short. They visited one club on Grosse Freiheitstrasse, where the owner exploded when he heard that they were part of the Beatles’ tour entourage, because he claimed that Paul had gotten his daughter pregnant. (This case lingered on until 2007, when DNA tests proved that Paul was not the father of Erika Hubers’s daughter Bettina, who had been born in December 1962.)

On June 27, they left Hamburg for the grueling journey to Tokyo. It should have been a sixteen-hour and thirty-five-minute flight, including an hour of refueling in Anchorage, Alaska, on what JAL proudly referred to as one of their “Polar couriers.” But on arriving in Anchorage the pilot was told to delay his departure, because Japan was being battered by Typhoon Kit, one of the most intense cyclones on record, with winds of up to 195 mph.

Brian Epstein was concerned about the Beatles being confined on the plane with no announced departure time, so he arranged with local ground staff to allow them to disembark and camp out in relative comfort at a nearby hotel. After the relevant paperwork was signed, a shuttle bus took them to the Westward Hotel, only a ten-minute drive from the airport. Here they were ushered in through a back entrance and taken up to suite 1050.

By the time they arrived at the hotel, word was already out that the Beatles were in Anchorage. For local teenagers who heard the news on the radio this sounded unbelievable. The city had a population of less than fifty thousand, was one of the most remote locations in the United States, and was certainly not on the regular tour circuit for pop groups. Rapidly fans made their way to the alley behind the Westward Hotel, hoping for a glimpse of the most famous pop group in the world, looking up to the tenth floor and singing “We love you, Beatles” to the tune of “Bye Bye Birdie.”

For the Beatles it was a day of frustration. They were tired. Their clothes were wrinkled. The view from the window was of a large construction site, a few scattered buildings, and a distant mountain range. George called the local gentlemen’s haberdashers, Seidenverg and Kay’s, and requested that two shirts and a hat be delivered to him. Room service sent up hamburgers and king crabs while three police officers stood guard in the hallway.

Robert Whitaker photographed them looking listless and bored as they waited. Ringo had a cassette recorder that he was using to tape an oral documentary of the tour; George was playing with a large Polaroid camera; and Brian Epstein was in another room of the suite conducting business by phone. Neither John nor Paul had brought anything with them to read.

The teenagers moved away from the hotel when a 10:00 p.m. curfew was enforced, and two hours later the Beatles were told that their flight would be leaving shortly for Tokyo. At 1:00 a.m. local time on June 28 they finally lifted off from Anchorage.

Assigned to look after them in first class on this leg of the journey was Satoko Kawasaki, one of the most English-proficient stewardesses employed by JAL. As a Beatles fan she had pitched for the job when she first heard of their booking, and the company’s PR chief had given it to her on the understanding that she could secure a publicity scoop by getting John, Paul, George, and Ringo to wear happi coats bearing the JAL logo. Photos of the Beatles in these silk jackets would be priceless in advertising the airline.

Paul, George, and Ringo with Brian Epstein in an Anchorage hotel room en route from Germany to Japan. They had to wait until a typhoon in Tokyo died down before they could complete their journey.

Getty Images/Robert Whitaker

John approached her to ask if she could iron his now crumpled jacket and trousers. She convinced him that the best solution was to slip on a happi coat that would hide all the wrinkles. As can be seen from Whitaker’s in-flight photos, that’s exactly what happened. Each of the Beatles slipped them on, and when they arrived at Haneda Airport at 3:39 a.m. on June 29 (they lost a day when crossing the International Date Line), they stood on the gangway blinking in the glare of flashbulbs, each wearing a happi coat, the JAL initials prominent.

The Beatles all piled into one vehicle while a dozen police cars, sirens wailing, rode in front and behind them on their way to the hotel. Security was exceptionally tight because of threats from a right-wing nationalist group that was outraged that these decadent Westerners were being allowed to perform at the Budokan, an arena built principally for martial arts contests in an effort to preserve Japanese culture. There was also dissension from educational groups who’d been leafleting high school pupils with the message that the music of the Beatles was synonymous with juvenile delinquency.

Japan was looking for its place in the postwar world. The nuclear destruction of Nagasaki and Hiroshima followed by the humiliating surrender to the Allies had happened less than twenty-one years before. Was the way forward to become more resolutely Japanese or to partner with Britain and America, openly exchanging influences? For those favoring the former course the Beatles personified a threat to their children. Not only were they seen as effeminate and nondeferential, but they also played American-influenced music that appeared to cause teenagers to lose their self-control.

The prime minister of Japan, Eisaku Sato, was opposed to their visit. Influential journalist Hosokawa Ryugen was outspoken in condemning it, and Matsutaro Shoriki, proprietor of the Yomiuri Shimbun, the newspaper financially backing the concerts, began to waver. Eventually, Yomiuri published a letter from the chairman of Budokan’s executive board explaining that the Beatles were reputable people who had recently been decorated by the Queen of the United Kingdom. They would not be desecrating the arena.

While there was concern over the visit in some quarters, others believed that a visit from the Beatles would mark Japan as modern, affluent, and forward-looking. There had already been great strides taken in putting the country back among the leading nations. The bullet train between Tokyo and Osaka, the world’s fastest, more than halved the traveling time. Then came the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, for which the Nippon Budokan was built to house the judo events, the first time that any martial art had become an Olympic sport. In four years’ time Osaka would host the World’s Fair.

The Beatles were controversial in Japan because on the one hand they were prosperous and had good business sense, things that Japanese elders admired, but on the other hand they represented antiauthoritarianism and individualism, things that the elders feared. The concerts were therefore divisive and had become an issue. In May, the newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun had reported, “Regardless of whether one likes it or not, the interest of the public is now focussed on the problem of the Beatles’ visit to Japan. . . . [It is] the biggest topic of discussion since the Tokyo Olympics.”

They were given the Presidential Suite at the Hilton, room 1005, which consisted of a large living room with sofas, an office desk, and a dining table with eight chairs and two bedrooms both with two single beds. Policemen were stationed outside the door, along the corridor, in every second room on the tenth floor, and elsewhere throughout the hotel. Brian Epstein and Peter Brown were down the hall in the equally ostentatious Imperial Suite. All entrances and exits to the building were under twenty-four-hour surveillance. The Beatles were kept in a virtual lockdown. They were not allowed to leave their rooms until the precise time when they needed to be escorted to the car that would take them to the concert.

At 2:30 they gave an hour-long press conference and photo op in the hotel’s Red Pearl Ballroom for the Japanese press and foreign correspondents. Before they’d even gotten into the elevator, they had to do a brief interview with E. H. Eric (actor Taibi Okada), the MC in charge of their concerts.

Q: Did you have a good sleep?

A: Yes.

Q: Did you have any knowledge of Japan before coming?

A: A little bit. Not much.

Q: How are the Japanese fans?

A: Great. They seem very great.

Q: I understand you have met your Queen. What was your impression?

A: She’s OK. One of the best.

Q: How did you feel when you received your medals?

A: It was nice.

Q: Which composer do you admire the most?

A: John Lennon.

Q: And, Paul’s marriage . . .

A: It’s not true. It’s wrong.

Q: How many times do you wash your hair in a week?

A: About once. It depends how dirty it gets.

They seemed emotionally drained and desperate to get away. John, who contributed the least, was making faces, dancing, and talking to other members of the Beatles retinue. Paul was doing his best to be diplomatic. Ringo was expressing concern that the beefed-up security might end up hurting the fans.

The mood continued into the press conference. Ringo and Paul smoked throughout. John had his elbow on the table and his head resting on his hand. Proceedings were slower than normal, because everything that was said had to be translated.

Q: You have attained sufficient honor and wealth. Are you happy?

JOHN: Yes.

Q: And what do you seek next?

JOHN: Peace. [Laughter]

PAUL AND JOHN: Peace.

PAUL: Ban the bomb.

JOHN: Ban the bomb, yeah.

TONY BARROW: There are three questions submitted to us from the Foreign Correspondents’ Association of Japan, I believe. And Mr Ken Gary of Reuters will represent the group in asking those questions.

KEN GARY: What do you think the differences are between Japanese fans of yours, and teenagers elsewhere in the world?

PAUL: I think the only difference with fans anywhere is that they speak different languages. That’s all. That’s the only difference. And they’re smaller here.

KEN GARY: Some Japanese say that your performances will violate the Budokan which is devoted to traditional Japanese martial arts, and you set a bad example for Japanese youth by leading them astray from traditional Japanese values. What do you think of all that?

PAUL: The thing is that if somebody from Japan—If a dancing troupe from Japan goes to Britain, nobody tries to say in Britain that they’re violating the traditional laws, you know, or that they’re trying to spoil anything. All we’re doing is coming here and singing because we’ve been asked to.

JOHN: Better to watch singing than wrestling, anyway.

PAUL: Yeah. We’re not trying to violate anything. Umm, we’re just as traditional, anyway.

KEN GARY: Why do you think that you are popular not only in western countries, but in Asian countries like Japan?

JOHN: It’s the same answer as before about the fans. They’re international. The only difference is the language. That’s why, you know, all different kinds of people like us.

RINGO: And also because the east is becoming so westernized in clothes, it’s doing the same with music, you know. It’s just happening that . . . Pretty soon we’ll all be the same.

Most of the questions, as usual, were about trivial issues from journalists hoping for a catchy headline. What was the origin of their haircuts? Would they pay to see themselves play? Why were they so successful? But at times, when asked about plans for the new record or to analyze the reasons for their success, they gave more thoughtful and prolonged answers.

The fact was that they didn’t plan their LPs ahead of time and had no idea why their music had made such an impact around the world. They knew they were good (although during this press conference Paul would say they were only “adequate” as musicians), but they also knew that merely being good was no guarantee of acceptance by the public.

Time magazine had recently published a feature in which it was suggested that “Norwegian Wood” was about an affair with a lesbian and “Day Tripper” was about discovering a girlfriend was a prostitute. The Beatles saw the issue in their suite at the Hilton and were amazed by this conclusion. “Psychologists have tried to analyze our music,” said John after reading it. “I don’t know why. There’s no hidden meaning in our lyrics. . . . We just write music.”

KEN GARY: But why is it you think that there is such fantastic response to your music? Is there something in it that people find in you a handy opportunity to let off steam?

JOHN: There’s no excuses or reasons for seeing us. People keep asking questions about why they come and see us. They come and see us because they like us. That’s all. There’s nothing else to it, you know. And they don’t have to let off steam at our concerts—they can go and let off steam anywhere.

PAUL: It’s the equivalent of a sort of football match for a girl, you know.

KEN GARY: Do you think that the response that people give, which sometimes gets violent and hysterical, do you think this is a good thing? Are you happy to see people behaving in this rather extravagant way?

PAUL: It doesn’t normally get violent, actually. You know, it may get hysterical. But it only gets as hysterical as men do at a football match. It’s no more hysterical than that. Nobody’s really trying to hurt each other. The thing is that obviously when you get a lot of people together, whatever they’re doing, there’s always a risk of that. But that’s what we were saying about security before. It’s always best if you can keep it so that it never gets out of hand. And it doesn’t very often get out of hand. In fact there are far more, I imagine, injuries at football matches all over the world than there are at our concerts.

JOHN: And less violence too.

KEN GARY: Would you then be disappointed if in fact you didn’t have this kind of response?

PAUL: No, you know. We’d just . . . If we didn’t have this kind of response, or we didn’t have this kind of life, you know . . . It’s no use really asking us what we’d do if we didn’t have it, ’cos if we didn’t have it we’d just do something else and we’d adapt to that. There’s no sort of great thing behind all of this. There’s no big message or anything, you know. We just get up and we sing, and people happen to like it, and we happen to like being liked. And that’s all there is to it, you know.

KEN GARY: You’ve been tremendously successful for a very long time now. Do you think this will continue?

PAUL: Do YOU think it will?

GEORGE: We don’t think anything. We think very little at all. You know . . . we just do it. And if the time comes when we don’t have an audience, then we’ll think then about it. But now we don’t think.

This was also the first press conference where the Beatles commented specifically about the war in Vietnam. They were asked how much interest they took in the situation. “Well, we think about it every day, and we don’t agree with it and we think it’s wrong,” said John. “That’s how much interest we take. That’s all we can do about it . . . and say that we don’t like it.” This provided an anxious moment for Brian Epstein, conscious that they were about to tour America, where this sort of comment could be inflammatory. He had advised them to steer clear of such controversial subjects and knew that Paul would have been much more diplomatic if he’d taken the question.

On the hot issues of the day—Vietnam, nuclear armaments, apartheid, civil rights—the Beatles took a liberal view but rarely stated it emphatically and had never hitched their wagon to a particular cause. In January Paul had been asked by Melody Maker what “Vietnam” suggested to him. “Bombs and shooting and killing and people doing things they shouldn’t,” he said.

The Tokyo dates introduced new elements to the Beatles’ story. Until now the police had been involved to control audiences and protect the group from overexuberant fans. Now the police were being used to foil potential acts of terrorism and violence. Likewise, political involvement had meant those in power acknowledging the Beatles’ positive spirit and giving them awards for their economic contribution. Now politicians in some parts of the world were denouncing them as morally degenerate and a threat to youth. This made touring feel increasingly dangerous as the music they’d created for pleasure seemed to fuel the fight between conservatives and liberals.

Tokyo had become such a battleground. For the visit 8,370 police officers ranging from plainclothes detectives to snipers had been involved in one of the biggest security operations ever mounted in the country. Additionally, the Kojimachi Fire Department was involved. Some Japanese commentators believed that the true total of personnel involved in crowd control and group protection was closer to thirty-five thousand.

The power of the Beatles phenomenon was becoming harder to fathom. What had happened so far in Britain, Europe, and America could be understood only through comparisons with Elvis, Johnny Ray, Frank Sinatra, and even Bing Crosby. It was the same youthful reaction but more intense and more widespread. What was astonishing was that young people in Tokyo, whose cultural educations had been so different, were responding in the same way as their counterparts in Tooting and Toronto. Also astonishing was the fact that the Beatles found themselves in the eye of a cultural storm as the postwar world adapted to new realities. Even two years before it would have been unthinkable that the Beatles’ presence—merely appearing on a stage and singing eleven songs, none of them with controversial content—would have vexed senior politicians, cultural commentators, radical political groups, Shinto priests, community leaders, and educators.

Dudley Cheke, the chargé d’affaires at the British embassy, saw the arrival of the “four young ‘pop’ singers from Liverpool” (as he described them in an internal memorandum later circulated in Whitehall) as a huge boost for the image of Britain in Japan. He wrote, “In sober truth, no recent event connected with the United Kingdom, with the sole exception of the British Exhibition in 1965, has made a comparable impact in Tokyo.”

He realized that the Beatles conveyed the impression of a forward-looking, exciting, irreverent, colorful, cheeky, relaxed, and experimental Britain rather than a fusty, dull, serious, and inhibited one. It was good for business; it exposed British culture and creativity to the world, and, on a personal note, Cheke wrote, “The Beatles’ visit enabled my wife and me to harvest goodwill among various highly-placed Japanese and foreign personalities who had seen in us the only hope of obtaining tickets for themselves or their offspring.”

The Beatles initially anticipated being able to go shopping and sightseeing the next day, but their police guards were insistent that they stay in their suite. The right-wing protestors were patrolling the streets in black and white trucks waving flags and playing martial music through loudspeakers, some of them holding banners saying GO HOME BEATLES. Extra police had been drafted in over the weekend, and there were forty armored personnel carriers on standby in case serious trouble broke out. They didn’t want to contemplate what could happen if an easily identifiable Beatle went wandering the streets without security.

John was the first to make a break. He put on a hat and sunglasses, borrowed Robert Whitaker’s press pass and camera, and slipped out of the hotel with Neil Aspinall. Together they walked down Omotesando, an avenue lined with zelkova trees, to the Oriental Bazaar, one of the best souvenir shops in Tokyo, where he picked up a china fukusuke figure (a man kneeling seiza-style with a large head and topknot) that he would later use on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, a small “god of fortune,” and a nineteenth-century snuff box for which he paid the equivalent of a thousand dollars. Then they went to the Azabu district, where John bought a pair of glasses. (It was in Azabu that Yoko Ono, his future wife, had taken refuge in an air raid shelter during the allied bombing of 1945.)

Paul was stopped by the police, as expected, when he tried to leave the Hilton, but, after a period of haggling, they agreed to let him out if he and Mal Evans would travel in a car packed with plainclothes detectives. They were given a tour of the Meiji Jingu Shrine and part of the grounds of the Imperial Palace before being spotted by photographers and bundled back into the car.

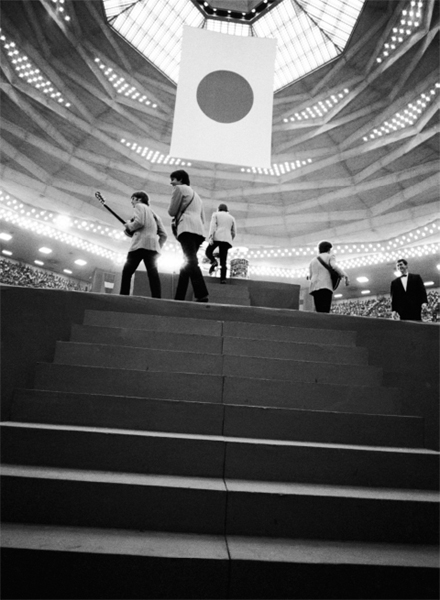

For the one concert on June 30 they stuck to the same set they’d used in Germany. They were wearing the same dark green Hung On You suits but with wine-colored shirts with long collars. The crowds screamed, but less volubly than was usual at a Beatles concert. This wasn’t from lack of enthusiasm—it was wild by Japanese standards—but because of the heavy police presence and the warnings issued against anyone standing, dancing, or leaving their seats. Uniformed officers took up the first few rows in each section, and in the balconies were agents with binoculars looking out for potential snipers.

The Beatles ascending to the stage of the Budokan in Tokyo.

Getty Images/Robert Whitaker

Musically, the group was creaky. Often the harmonies were off-key, and “Paperback Writer,” which they’d only played live six times before, sounded flat because it had been recorded using both ADT and double-tracking. When John introduced songs, he frequently couldn’t recall if they’d been singles or LP tracks and, if from LPs, which ones. They’d learned that when they came to a difficult part in a song—something underrehearsed or impossible to recreate in a live situation—all they needed to do was wiggle their heads and the crowd’s screams would disguise the fault.

The concert was a success, not least because the agitators hadn’t won the day. The protests had been quelled, the armored vehicles hadn’t been needed, and no one had kidnapped a Beatle and forced him to undergo an involuntary haircut (as was threatened).

The effect on those who saw them was profound, and the ripples would spread out. Reviewer Shuji Terayama wrote, “It was a celebration which came close to spontaneous human combustion. The energy of the fans will change Japanese history.”