We never expect to be knocked because we feel harmless. We don’t want to offend but we can’t please everybody.

—PAUL, 1966

The Beatles whiled away their time in their Tokyo hotel suite before the two daily shows on July 1 and 2 by painting and buying goods from local tradesmen who they called in. They had bought paint sets designed for Japanese brush painting, and for two mornings the four Beatles sat at the dining table with a thirty-by-forty-inch canvas in front of them, each diligently decorating his own corner in his own style. While working they listened to the fourteen songs they’d just recorded back in London to help them decide on the sequence in which the tracks would appear on the still-unnamed LP. In the center of the canvas stood a table lamp, leaving a blank circle that they would later use for their autographs.

John and Paul were at one side of the table, George and Ringo at the other. Their contributions were all different (Paul’s looked like a rainbow-colored uterus; Ringo’s carefully outlined shapes were reminiscent of Joan Miró) but had in common the feel of abstract expressionism mixed with contemporary psychedelic painting. Once they started it they became preoccupied, anxious to return to it after performing, and it provided them with a collaborative escape from the surrounding demands. Robert Whitaker later said of the exercise, “Other than their music this painting was the only creative enterprise I saw the Beatles undertake as a group. I had never seen them so happy—no drink, no drugs, no girls—just working together with no distractions.”

They donated the completed work to Tetsusaburo Shimoyama, their local fan club president, who would eventually sell it to a collector. In 2012, it was sold at auction in America for $155,250. Cleaners found other small drawings and paintings in the trash bins. A cartoon by John featured a man with nine strands of hair, one of which dangled to street level and had a dog attached to it.

The traders who showed off their wares provided the other distraction. From them the Beatles bought kimonos, jade, Noh masks, netsuke, incense holders, carvings, kites, gold lacquer boxes, sunglasses, and electronic goods. Sushi chefs brought in trays of fresh fish, and geisha girls offered their services. Tats Nagashima, known for his generosity toward acts he promoted, bought each of them an expensive Nikon camera and gave movie cameras to Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall.

Ringo and John with the painting all four Beatles created while confined to their hotel suite in Tokyo.

Getty Images/Robert Whitaker

The matinee concert on July 1 was at two o’clock, and the opening half featured local acts each playing one or two numbers of a uniquely Japanese take on Western rock. Drummer Jackey Yoshikawi appeared with his group, the Blue Comets; the singer Isao Bito performed Cliff Richard’s hit single “Dynamite”; and Yuya Achido, who would go on to become friends with John, opened the show with a specially written song called “Welcome the Beatles.”

The Beatles, wearing gray suits with thin orange stripes from Hung On You, were filmed by Nippon TV, as they had been the day before, for a quickly edited show transmitted that night on NTV Channel 4 as The Beatles Recital: From Nippon Budokan, Tokyo, while they were back on stage for their second show. Some fans complained that at half an hour the set was far too short for the price charged (tickets were the equivalent of $16 for the “cheap” seats and $24 for the rest).

The final concerts were on July 2, and between the two shows they continued to ponder the LP title. New suggestions included “Abracadabra” (Paul still pursuing the theme of magic), “Beatles on Safari” (a nod to the Beach Boys), and “Freewheelin’ Beatles” (a tribute to Dylan), but again nothing was settled.

Until “Revolver,” suggested by Paul. It was a succinct but playful title. A revolver was a handgun with a rotating bullet chamber, but it could also be another word for anything else that rotated, like a record. An LP was a revolving disc. Asked about the title, John denied that there was a special significance to the name yet at the same time implied that it could have multiple meanings. He said, “It’s just a name for an LP, and there’s no meaning to it. Why does everyone want a reason every time you move? It means Revolver. It’s all the things that Revolver means, because that’s what it means to us, Revolver and all the things we could think of to go with it.”

Some of the things that “go with” the word “revolver” are “revolution,” “evolve,” and “evolution”—words that have roots in the Latin volvere, which means to roll (and eventually lent its name to rolled parchments—volumen—and left us with the word “volume” for books). The album certainly announced both a revolution, in sound as well as attitude, and an evolution of their art. In 1968 John would say, “The Beatles were part of the revolution, which is really an evolution, and is continuing.” From the Hilton they sent a telegram to EMI in London announcing Revolver as the title of their next LP.

THE BEATLES WERE CERTAINLY REVOLUTIONARY FOR JAPANESE youth. Their appearances in Tokyo signposted a new way of living that was less reflexively reverent of tradition, self-restraint, and formality. Literature professor Toshinobu Fukuya has since written, “In their three days of concerts in Tokyo, the Beatles demonstrated to Japanese youth that one did not always have to obediently follow arrangements prescribed by adults; it was possible to follow one’s own path and still be socially and financially successful in life.”

On July 3 they took a flight out of Haneda Airport bound for Manila via Hong Kong, where they deplaned for seventy minutes. During the stopover they visited the VIP lounge of Kai Tak Airport, where John and George did interviews with local radio reporters. The rest of the journey, with Cathay Pacific, was on a narrow-body Convair 800, and everyone on board was made aware of the VIPs in first class. The Philippine promoters, Cavalcade International Productions, had endorsed Cathay as the official incoming carrier on their posters and tickets, and Cathay had issued all passengers with a souvenir folder including a four-by-five-inch glossy black-and-white photo of the group (some of which John defaced with a pen while feeling bored on the flight).

There had been no death threats from Manila and no suggestion that the Beatles were a challenge to political stability. The Philippines was proud of its European heritage and its current ties with America. Yet after they landed at 4:30, the Beatles’ party sensed an air of tension and barely concealed disdain. It was routine that the group and their team would disembark from an airport terminal and be whisked away in limousines to avoid press attention and fan mania. Their equipment would clear customs separately, with Mal Evans in attendance, where personal bags were treated as diplomatic pouches and therefore immune from scrutiny. These bags were where they would hide their illegal substances.

At Manila they left the plane in the normal way and their bags were placed on the runway, but before they could collect them the group was roughly bundled into the back seat of a waiting car, and the driver pulled away, leaving behind the bags as well as Neil Aspinall and Brian Epstein. Customs collector Salvador Mascardo was insistent that carry-on luggage had to be inspected. They didn’t know why they’d been separated from their possessions. Would their pot stash be discovered?

They were driven ten miles to the Philippine Navy Headquarters on Dewey Boulevard, overlooking the city’s marina. Here they were they were interrogated by forty journalists in the appropriately named War Room. They were in a more frivolous mood than in Japan or Germany, giving answers that were as inane as the questions. When did they last cut their hair? “Nineteen thirty-three,” said John. What was their favorite song? “God Save the Queen.” What was their second favorite song? “God Save the King.” Their unease about the earlier treatment at the airport surfaced when they were asked what they’d be telling the soon-to-be-touring Rolling Stones about the Philippines. “We’ll warn them.” What was the title of their next song? “Philippine Blues.”

Security in the city was as intense as it had been when US president Dwight Eisenhower visited in 1960. Police officers, motorcycle cops, armored cars, fire trucks, riot squad jeeps, and police prowl cars controlled the ten thousand fans that turned up at the airport. The army was on red alert. “Is there a war in the Philippines?” an unidentified Beatle was quoted as saying shortly after arrival. “Why is everybody armed?”

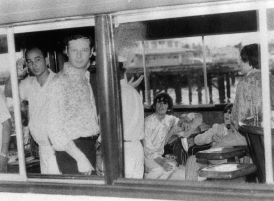

Following the press conference John, Paul, George, and Ringo were briskly ushered out of the back entrance of the building to an awaiting yacht, the Marima. Photographers gathered on the water’s edge and begged the Beatles to line up and peer out of a cabin window. They seemed willing, but the newly arrived Brian Epstein didn’t want them manipulated in this way. He was already furious at being forced to pay a bond on the band’s equipment to the airport customs agents.

The craft belonged to Don Manolo Elizalde, one of the founders of the Manila Broadcasting Company, who’d made his fortune from steel, hemp, paint, and wine, and was a friend of promoter Ramon Ramos as well as President Ferdinand Marcos. But the host for the evening was his twenty-four-year-old son, Fred, who’d recently graduated magna cum laude from Harvard. With him were his sister; his girlfriend, Josine Loinaz (Miss Manila 1966); and a handful of employees from Cavalcade International. Epstein ordered two TV men from Channel 11 (owned by Elizalde Sr.) to leave the boat, unaware that they had been promised an exclusive interview as payback for the group’s use of the yacht.

As the Marima pulled out into Manila Bay, the Beatles began to relax. They were away from the bustle, the guns, and the fans. They sunbathed on the deck wearing rubber sandals, listened to tapes of Ravi Shankar, and drank whiskey and Cokes. Loinaz and Fred Elizalde found them charming. The Beatles lit up and openly shared their dope with Elizalde and some of his male friends. Epstein, however, was still frantic. Not for the first time he felt that events were slipping out of his control. He’d just learned that the plan, approved by NEMS’s Far East booking agent, Vic Lewis, who had been the one to negotiate directly with Ramos and establish the itinerary, was for the Beatles to stay on the boat rather than at the hotel for security reasons. They could easily protect and police a yacht, but not a city-center hotel.

From top: The Marima. Brian Epstein, George, John, and Paul on board the Marima. Paul, George, and John.

Edward de los Santos (Pinoy Kollektor)

As the evening drew on, food was served—consommé, fried chicken, filet mignon, mashed potatoes, carrots, and sweet peas—but then one of Elizalde’s brothers arrived on a launch with eighteen of his friends, and Epstein declared it all over. The Beatles, who’d just started their consommé, would return to the yacht basin and be transferred to the luxurious turn-of-the-century Manila Hotel on Rizal Park, where the rest of the team was staying. Because the hotel was fully booked, rooms had to be swapped to create space, and they weren’t finally checked in until four in the morning.

What they weren’t aware of at this point was that the day’s issue of the Manila Times had announced that at eleven o’clock the Beatles would be visiting the presidential palace, Malacañan, as special guests of President Ferdinand Marcos and his wife, Imelda, who had invited three hundred children and young people to meet the group. All that was mentioned in the itinerary was that at 3:00 p.m. they might “call in on the first lady . . . before proceeding on from the Malacañan Palace directly to the stadium.” Phrased in this way it appeared to be a casual suggestion, but even so the time was wrong, and in the confusion over the accommodations, the arrangement hadn’t been discussed with Epstein or the Beatles.

It appears that Ramos had been told by the palace to deliver the Beatles, but, knowing that their likely response was to decline, he had stalled by burying the invitation in the small print, hoping for a compromise on the day. Imelda Marcos was a formidable woman who expected her requests to be fulfilled, but Brian Epstein and the Beatles were equally stubborn. Ramos was caught in the middle.

The Beatles routinely turned down invitations to such official events around the world ever since the hair-snipping incident at the Washington, DC, embassy reception. They didn’t want to be treated as playthings or figures of amusement by people of privilege and power. Besides, in practical terms, the hours before a concert were always a time of relaxation and preparation.

Ferdinand Marcos had won the presidential election in November 1965 and was enjoying his honeymoon period. He was not yet regarded as a dictator and had broad popular support. He shared his birth year with John Kennedy, as Imelda did with Jackie Kennedy, and they tried to replicate the sheen of the Kennedys’ Camelot, hoping that it would result in a similar love affair between people and power in their country.

Paul got up first on the morning of July 4, which was the day of their two concerts, blissfully unaware of the 11:00 engagement, and went with Neil Aspinall to Makati, the financial district of the city, and then to an adjacent shanty town settled by squatters where he bought a couple of paintings as souvenirs. After this the two of them went to the beach, where they smoked a joint.

Chaos was ensuing at the hotel by the time they got back. A reception team from the palace dressed in military uniforms had banged on the door of Vic Lewis’s room to tell him that the Beatles were expected at the palace by eleven and that everyone was waiting. As he’d been the one to deal with Ramon Ramos and Cavalcade, Lewis was deemed personally responsible for getting the group there on time. “This is not a request,” they told him. “We have our orders.” He in turn found Epstein, who was in the restaurant eating breakfast, and tried to persuade him to at least have the Beatles drop in to avoid a huge controversy, but Epstein was adamant that they would do no such thing. “I’m not going to ask the Beatles about this,” he said dismissively. “Go back and tell the generals we’re not coming.”

Ramon Ramos, Colonel Morales of the Manila Police District, and Colonel Flores of the Philippine Constabulary came to the fourth-floor suite to persuade the Beatles in person to honor the appointment, but the more the Filipinos argued their case, the more contrary the Beatles became. Over the years they had grown to dislike hobnobbing with dignitaries and their offspring. This was not their natural audience, and often these people didn’t personally like the Beatles’ music but used the occasion to boost their own standing. “If they want to see the Beatles, let them come here,” said John. Morales explained to him that the “they” included Ferdinand Marcos. “Who’s he?” asked John.

Even Dudley Cheke in Tokyo hadn’t been able to interest the Beatles in a cocktail party or reception in their honor. “This was only because they felt unable to accept our invitations,” he informed his superiors in London. “Their manager had been at pains to explain to me in correspondence which we exchanged before their arrival that they had decided after experiences in Washington, not to go to any more Embassy parties.”

British diplomatic pleading didn’t help in Manila either. The Beatles had a northern working-class suspicion of officialdom. The British ambassador, John Addis, was away on business, and so it was left to his chargé d’affaires, Leslie Minford, to explain that Filipinos were proud of their hospitality and that it was considered very impolite to refuse it. To invite someone into your house was the supreme gesture of friendship. He also pointed out that all the personal security the Beatles were enjoying came courtesy of the palace and could be withdrawn on short notice if they appeared to be ungrateful.

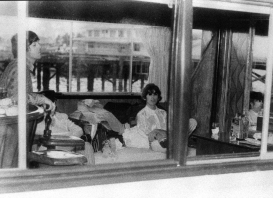

A souvenir program for the two concerts the Beatles gave in Manila, July 4, 1966.

Edward de los Santos (Pinoy Kollektor)

The children who’d gathered in expectation were either related to high-ranking government officials or friends of five-year-old Irene, eight-year-old Bongbong, and ten-year-old Imee, the offspring of the president. At noon Imelda gave up. Many of the children stayed, but eventually they all left, and Irene, Bongbong, and Imee tore up their concert tickets in disgust. (Imee said that the only Beatles track she’d ever liked was “Run for Your Life.”) The big story now was that the Beatles, the longhaired lads from Liverpool, had publicly rejected the president, the first lady, and a few hundred Filipino children and were not going to apologize.

The shows were at 4:00 and 8:30 at the Rizal Memorial Football Stadium. The stage was small, wire fencing had been erected in front of it to prevent any mobbing, and blocks of seats had been reserved for dignitaries who now refused to come. The six Filipino opening acts (whose combined performance lasted twice as long as the Beatles’ set) were the same acts who’d recently supported Peter and Gordon in Manila, and they performed the same songs and told the same jokes.

The Beatles were hard to hear and even harder for most of the crowd of thirty thousand to see. Many people thought they seemed to be merely going through the motions. Between shows they stayed with each other in a specially constructed dressing room on the field behind the stage. For the second show the organizers had improved the sound a little, but the lighting shone too brightly in the eyes of the group.

The Filipino novelist and historian Nick Joaquin (also known as Quijano de Manila), who reviewed the show for a Manila newspaper, wrote,

So alive, original and imaginative were their two films one expected a live show of theirs to be just as different and inventive. Alas, they performed like any local combo, only not so spiritedly. There was no style, no verve, no poetry to their performance. They stood before mikes and opened their mouths, that was all. It was a one-two-three, “Now we’ll do this song.” They sang. “Now we’ll do this next song.” They sang. And so on, until they had sung, very listlessly, all the ten songs they had to sing [they had dropped “Nowhere Man” for this show]. Then they bowed out. Who would have cared for an encore? Even the periodic squealing of girls seemed mechanical, not rapture but exhibitionism. The audience was too vexed over the poor sound, if they could hear at all, and the languor on stage, if they could see at all. Those who couldn’t see or hear didn’t miss anything.

Between shows, back at the hotel, Epstein, Tony Barrow, and Vic Lewis had watched the TV news, which was dominated by the story of how the Beatles had stood up the first lady. It showed the forlorn faces of the children and the place cards of John, Paul, George, and Ringo being removed after the group’s nonappearance. “This was the most noteworthy East-West mix-up in Manila for many years,” intoned the announcer.

Barrow thought the best immediate fix was to have Epstein make a public statement. He composed a brief speech and invited Channel 5, the government-sponsored TV channel, to come to Epstein’s suite, where he would make an announcement. The offer was accepted, and Epstein explained that he and the Beatles were unaware of the invitation. “The first we knew of the hundreds of children waiting to meet the Beatles at the palace was when we watched television earlier this evening.”

This statement was partly true. They hadn’t known the extent of the welcoming party until they saw the images, but of course they had known about the invitation since early morning. What he wasn’t going to say in the broadcast was what he later admitted on reflection, “Even if we had [received the invitation] we’d have turned it down. I’d much rather the boys met 300 average children in India than 300 kids who happened to be at the palace because their parents knew somebody.”

When Epstein’s statement was broadcast, as part of a late-night news bulletin, the sound was distorted, although it seemed to be fine during the rest of the transmission. Before midnight Vic Lewis was taken to a police station where he was interrogated for three hours. “Why did you snub our country?” he was asked. “You represent the Beatles. You did not bring them to the palace today.”

Lewis contacted the British embassy to let them know what was happening, but no report of this intimidation or the death threats that Barrow was told had been received by embassy officials was reported in written exchanges between chargé d’affaires Minford and London. Minford sent a telegram to the Foreign Office explaining the situation so far, but appeared unruffled and his tone was matter-of-fact. The Beatles had failed to keep an appointment with the first lady, and it had been “treated as a snub,” but he didn’t think it had been intended as one. However, he wrote, “There is a possibility that a technical hitch over payment of Philippine income tax may delay their departure.” But not to worry; he had been “in touch with Philippine authorities to smooth out local difficulties.”

Lest London should think that he or the ambassador had been lax in their duties, he made the point that “at no time and at no stage was I or the Embassy consulted about the arrangements of the Beatles’ visit to Manila.” He had been in touch with Imelda Marcos “to express regret that there should have been any discourtesy which I have been assured by the Beatles was in no way their intention.”

On July 5, the Beatles were ready to fly to Delhi, India, for an overnight stay en route to London. It was George’s big dream to visit the country of gurus, meditation, yoga, sitars, and Ravi Shankar, and he had persuaded Neil Aspinall to join him and was hopeful that the rest of the group would also come. They packed their bags early and nervously paced around their suite. They’d been shown copies of Manila’s morning papers, where the headlines were all about the failed meeting at the palace. The Manila Chronicle was typical. In bold letters at the top of the front page it said FUROR OVER BEATLES “SNUB” MARS SHOW.

It soon became clear that part of their punishment was to have special treatment and privileges removed. The hotel reception turned frosty, security was withdrawn, and no cars arrived to take them to the airport. At shortly after 8:00 a.m. a representative of the Bureau of Internal Revenue visited Vic Lewis in his room with a tax bill. Lewis explained that Cavalcade had agreed to pay all local taxes. “Your fee is taxed as earnings,” said the impassive official. “This is regardless of any other contracts.” The regime was coming down hard.

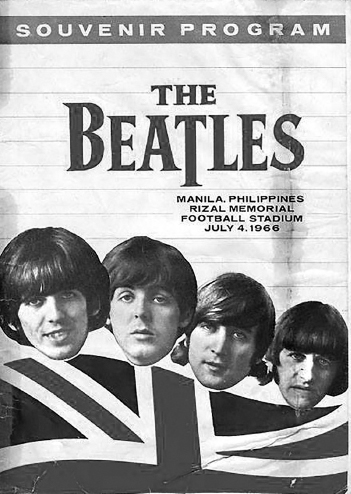

At the airport, the porters refused to carry the Beatles’ luggage, leaving them struggling to get through the crowds. When they entered the terminal, the escalator to take them to the first-floor check-in was turned off. They then made the mistake of making a dash for the desks, thinking that by cutting down on time they’d make themselves less vulnerable. However, the sight of four fleeing Beatles drew even more attention, and soon they found people chasing after them who didn’t know what the pursuit was about.

Fights broke out. Citizens loyal to Marcos (or possibly undercover agents) were determined to show their displeasure by roughing up the Beatles. Ringo and John were apparently both punched. Brian Epstein was knocked to the ground, and Mal Evans was kicked so hard his leg bled. This had all been orchestrated by the airport manager, Willy Jurado, who himself joined in the melee in the belief that to protect the honor of the Marcos family was to protect the honor of the Filipino people. In 1984, now living in San Francisco, Jurado was happy to boast of his activities. “I beat up the Beatles,” he told Bob Secter of the Los Angeles Times, who was researching a story on the Marcos regime. “I really thumped them. First I socked Epstein and he went down. . . . Then I socked Lennon and Ringo in the face. I was kicking them. They were pleading like frightened chickens. That’s what happens when you insult the First Lady.”

After playing the bad cop, Jurado then played the good cop by waving off fellow attackers and getting the Beatles to a desk for their papers to be sorted. He asked for a gangway to be created to expedite them, but as they headed for the plane there was more cuffing, pushing, and spitting. When some fans of the group started crying because of the mistreatment of their heroes, the rest of the crowd turned on them as if they were traitors.

Neil Aspinall (left) under attack at the Manila airport while John and Brian Epstein’s assistant, Peter Brown (far right), look on with concern. Mal Evans has his back to the camera.

Getty Images

Once on the plane they thought their ordeal over. The Beatles kissed their seats out of sheer joy. But before takeoff officials boarded and demanded that Mal Evans and Tony Barrow accompany them back to the terminal, as their papers weren’t in order. According to their records, the two men had never entered the Philippines, and there were no appropriate stamps in their passports. As Evans walked down the aisle, he asked George to tell his wife, Lil, that he loved her. He was seriously concerned that he was about to be imprisoned. After an anxious forty minutes Barrow and Evans were allowed back on the plane.

Epstein was sweating in his seat. He felt that he had let the Beatles down, especially by not having paid more attention to the itinerary submitted by Ramon Ramos. Now his fellow passengers were furious with him for delaying their flight. Vic Lewis lost his temper with Epstein over the tax issue, and Epstein accused Lewis of only being concerned about money. It took Peter Brown’s intervention to stop the spat from turning physically violent. Epstein now looked ill rather than merely dejected. Finally, at 4:45 p.m., KLM flight 862 took off for its three-thousand-mile journey to India.

Back at the British Embassy chargé d’affaires Minford prepared his second and final communiqué on the incident. He told the Foreign Office in London that “a few persons at the airport showed unnecessary zeal in being unpleasant to them during the departure formalities.” But he assured his bosses that it had all been settled by the intervention of Mrs. Marcos’s brother Benjamin Romualdez.

President Marcos then took the unusual step of issuing a press statement, saying that he’d ordered the controversial tax and customs claims to be lifted. He spoke of his regret that the affair had happened and referred to it as a “misunderstanding.”

“The incidents at the airport shouldn’t have happened since they were a breach of Filipino hospitality and totally disproportionate to the triviality of the whole matter. The president and Mrs. Marcos, unlike the reaction elsewhere in Manila, were not at all ruffled by the non-appearance of the Beatles at the palace and were in fact surprised at the high feelings engendered in other sections of the community.”

The facts of what happened that day are still not clear. Were the Beatles ever paid for their two appearances in Manila? Did Epstein finally pay the $17,000 tax demand? In 1971, when trying to clear up Apple’s finances, Peter Brown wrote to John asking if he could recall being paid or seeing Epstein hand over money to the authorities while on the grounded plane. John replied that he thought Epstein gave the money demanded but couldn’t be sure. All he knew for certain was that the Beatles didn’t receive their fee and that the flight wasn’t delayed because of alleged unpaid taxes or unstamped passports but because the authorities wanted to frighten them.

Nick Joaquin, who’d already been perceptive in his review of the concert, made an astute assessment of the whole fiasco in an article published in Manila two weeks later. In his estimation, the issue was not a simple one of a political leader being rebuffed. It was a deeper matter of official culture fearing the challenge posed by change and punishing the Beatles because they represented a free spirit that ran counter to the Philippine ideals of order and formality. As in Japan, the controlling powers wanted to benefit by hitching themselves to the creativity, popularity, and commerciality of the Beatles without comprehending what they represented at a deeper level and what it was about them that tapped into the zeitgeist.

“Because the Beatles are supposed to be very ‘in,’ we had to make all that fuss over them to prove that we, too, are ‘in’—but do we ever ponder why the Beatles are so ‘in’ with Westerners?”

He suggested that Filipinos tended to overlook the essence of the Beatles, which was “the delight in doing what everybody else is not doing, or the irreverence for mores and manners, or the urge to be singular, spontaneous, original, new, or the courage to be unconventional, unpleasant, outside, not with it,” and argued these were “the very qualities we need to get us moving.”

He saw the Beatles as an affirmative voice in the world—a “Yeah, Yeah, Yeah” at a time when there was too much “No, No, No.” He quoted John as saying, “The Bomb? Nuclear disarmament? Well, like everybody else I don’t want to end up a festering heap, but I don’t stay up nights worrying. I’m preoccupied with Life, not Death.”

Ultimately Joaquin felt the Beatles had “failed” in the Philippines in the sense that even though the country liked their veneer and wanted to emulate the long hair and the guitar sounds, it was resistant to their implicit call for change. “How could they not flop in a land which only wants not to be disturbed, not to change, not to be shocked?” he asked. “Having made a career of outrageousness, they have taken for granted that any audience that asks for them is asking to be outraged. If they made a mistake in Manila, the mistake is flattering to us: they assumed we were in the same league. But they were Batman in Thebes.”

When the Beatles touched down in Delhi late at night, they thought they were entering a country where they were unknown and where they would therefore be left alone, but there were over five hundred fans to greet them at the airport, and an impromptu press conference had to be organized to satisfy a contingent of journalists. They were then driven to the Oberoi Intercontinental on Wellesley Road, their home for the next two nights.

It was while at the Oberoi that discussion turned for the first time to the future of the group. Epstein’s anxiety, which at first had seemed to be a result of the strain experienced in Manila, was more serious. He had developed a fever and had to remain in his room, which left John, Paul, George, Ringo, and Neil Aspinall with time alone to talk to each other. There was a consensus that Epstein was losing his grip because the job had grown too big for him. A year before, overexcited fans breaking through barriers outside a provincial English cinema where the group were about to perform would have been the worst thing that could happen. Now it was mob revolt, violence, political backlash, and threats of assassination.

Aspinall told them that Epstein was already planning tours for 1967. George wanted to know whether these were going to become an annual event. “Nobody can hear a bloody note anyway,” said John. “No more for me. I say we stop touring.”

George had persuaded the others to join him on this Indian detour, but during the flight they changed their minds (they were tired of travel and wanted to get home). By then KLM had sold the Delhi-to-London section of the flight, so John, Paul, and Ringo had to honor their original bookings.

On their first day they shopped for musical instruments, visiting the Lahore Music House and then the Rikhi Ram Musical Instrument Manufacturing Company at Marina Arcade on Connaught Place. The Rikhi Ram store was small, and within minutes fans were clustered outside on the street. Bishan Dass Sharma, the son of the late founder, arranged for a selection of instruments (a tambura, sitar, tabla, and sarod) to be taken to the Oberoi later in the day along with instructors to give the Beatles basic lessons in tuning.

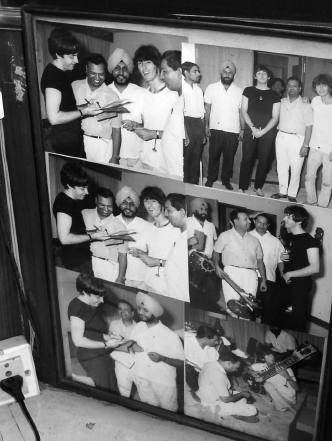

John, Paul, and George receiving basic instruction in tuning their newly purchased Indian instruments, July 1966 (photos on display at the Rikhi Ram music store in New Delhi).

Steve Turner

In the afternoon they were given a tour of Delhi before being driven to villages outside the city. Decoy limousines were used at the main entrance of the Oberoi to distract the crowd of fans and journalists that had gathered while the Beatles were whisked out of an underground garage in black Cadillacs driven by Sikh chauffeurs in blue turbans.

Tipped off by his driver that the Beatles were going to be leaving from a back exit, the local bureau chief for the Associated Press (AP), Joe McGowan, broke from the press pack and gave chase in the bureau car. A wild drive ensued, and when all three cars got to the city outskirts, the Cadillacs carrying the Beatles stopped, and Paul and John got out to confront McGowan, who explained to them that he was from the AP, the world’s largest news agency, and just needed a couple of quotes. Paul told him about the problems in Manila and offered apologies to Imelda Marcos. McGowan was happy with his haul and left them to continue their trip unmolested.

The Beatles were surprised at the contrast between the wide avenues that the British had lined with their administrative buildings and executive bungalows and the narrow streets choked with cattle, people, and cars that spread out through the rest of the city. They were even more surprised by the primitive conditions in the outlying villages, where camels were still used to hoist up water buckets from wells and the children gathered around to beg for money, or “baksheesh.” They visited the famous Red Fort and were taken to Qutub Minar Park, where, at the summit of a flight of steps, there was an iron post that it was customary to back up to and wrap your arms around in order to bring good luck. At night, according to a letter written by George, the traveling party availed themselves of “hookers etc.,” and Neil Aspinall paid the price by getting “Oriental Crabs.”

The visit was fleeting yet significant. It was the Beatles’ introduction to Indian culture—something they’d explore more fully when returning in 1968 to study meditation in Rishikesh—and also their first experience of real poverty. George said it was “quite an eye-opener” for him when he realized his camera was worth more than some of the villagers he photographed would earn in a lifetime. Ringo commented, “India was the first foreign country I ever went to. I never felt Denmark or Holland or France were foreign, just that the language was different.”

They flew from Delhi to London with BOAC on the night of July 7. Either on the flight or earlier in the day while still at the Oberoi the Beatles announced to Brian Epstein that they planned to stop touring after fulfilling their commitments in America. The pressures were too great, the dangers too real, the expectations too high, and the rewards for playing too low. They felt that they had outgrown that stage of their career and looked forward to concentrating on the part of their work that they found most fulfilling—writing and recording.

Epstein took the news badly. During the flight he broke out in a rash and felt so ill that the pilot radioed ahead for an ambulance to meet the plane in London. Before landing Epstein turned to his NEMS colleague Peter Brown and asked, “What will I do if they stop touring? What will be left for me?” Brown tried to console him. “Don’t be ridiculous,” Brown said. “There’s lots for you to do.”

On their arrival on the morning of July 8 the Beatles were greeted by screaming fans, as they had been after every overseas tour since Beatlemania took hold in 1963, and then they headed straight to a business lounge for brief press interviews where the journalists were eager to hear exactly what had happen to them in Manila.

Q: At the airport, did they come up and start physically threatening you?

PAUL: We got to the airport and our road managers had a lot of trouble trying to get the equipment in because the escalators had been turned off, and things. So we got there, and we got put into the transit lounge. And we got pushed around from one corner of the lounge to another, you know.

JOHN: [impersonating and demonstrating by shoving Paul repeatedly in the shoulder] “You’re treated like ordinary passenger!! Ordinary passenger!!” . . . Ordinary passenger, what, he doesn’t get kicked, does he? [Beatles laugh]

PAUL: [laughs] And so they started knocking over our road managers and things, and everyone was falling all over the place.

Q: That started worrying you, when the road manager got knocked over.

PAUL: Yeah, and I swear there were thirty of ’em.

Q: [turning back to John] What do you say there were?

JOHN: Well, I saw sort of five in sort of outfits, you know, that were doing the actual kicking and booing and shouting.

Q: Did you get kicked any?

JOHN: [giggling] No, I was very delicate and moved every time they touched me. [Beatles laugh]

JOHN: But I was petrified. . . . I could have been kicked and not known it, you know. We’ll just never go to any nut-houses again.

Q: Would you go to Manila again, George?

GEORGE: No, I didn’t even want to go that time.

JOHN: Me too.

GEORGE: Because we’d heard that it was a terrible place anyway, and when we got there . . . it was proved.

Asked again whether they would ever return to the Philippines, John muttered under his breath, “We should have taken over Manila in the war,” then commented in his normal voice, “No plane’s going to go through there with me on. I won’t even fly over it.”

Brian Epstein went directly home to his sickbed and was later diagnosed with glandular fever (infectious mononucleosis). He canceled a trip to America set up for him to do advance preparation for the upcoming tour. His doctor, Norman Cowan, recommended taking time off work and getting out of London if possible. At the end of the month Epstein chose to go to Portmeirion in North Wales, a tourist village on the sea built entirely in an Italianate style starting in the 1920s, where he rented the gatehouse that straddled the main entrance to the village.

Brian Epstein came to recuperate at Portmeirion in Wales after the Far East tour.

Steve Turner

Few places could seem further removed from the center of the cultural hurricane of the Beatles than Portmeirion. After the high security of Tokyo, the violence of Manila, and the dust and dirt of Delhi, he was safely ensconced in a fairytale village full of classical sculptures, trees, gardens, lawns, narrow streets, and colorfully painted buildings. Seagulls wheeled overhead, fresh air blew in from the sea, and there was a large deserted beach on which to take walks.

THREE DAYS BEFORE EPSTEIN LEFT FOR WALES NME PREVIEWED Revolver ahead of its British release. The reviewer was Allen Evans, and it was written in his typical fusty style. “Taxman” was “a fast rocking song with twangy guitar,” “Eleanor Rigby” was a “folksy ballad,” “Love You To” was “an Oriental-sounding piece,” and “Doctor Robert” was “John Lennon’s tribute to the medical profession about a doctor who does well for everyone.” “Tomorrow Never Knows” clearly floored Evans. It was John telling you to turn off your mind and relax, but, Evans worried, “How can you relax with the electronic, outerspace noises, often sounding like seagulls?”

Older writers like Evans could describe the songs in a cack-handed way but were not yet able to successfully evaluate them or comprehend music that didn’t fit into the preordained categories of rocker, ballad, catchy, slow, fast, or lyrical. Presented with an LP that would go on to be critically regarded as one of the greatest recordings of the twentieth century, all Evans could conclude was, “The latest Beatles’ album, Revolver, certainly has new sounds and new ideas. You’ll soon all be singing ‘Yellow Submarine.’”

Disc and Music Echo gave the LP to Ray Davies of the Kinks for a track-by-track appraisal, and he was surprisingly mean-spirited about it. “Taxman” was “a bit limited,” “Eleanor Rigby” sounded as though it had been written “to please music teachers in primary schools,” “Love You To” was “the sort of song I was doing two years ago,” “Yellow Submarine” was “a load of rubbish,” “And Your Bird Can Sing” was “too predictable,” and “I Want to Tell You” was “not up to Beatles standard.” The only tracks he mustered enthusiasm for were “Good Day Sunshine,” “I’m Only Sleeping,” and “Here, There and Everywhere.” His overall verdict was that it wasn’t as good as Rubber Soul.

There had been bad blood between the Kinks and the Beatles since they played together on the same bill in 1964. John upset Davies backstage by saying, “We’ve lost our set-list, lads. Can we borrow yours?” implying that the Kinks, who had only released two singles at that point, were mere imitators. Paul was more respectful. When the Kinks released “See My Friends” in 1965, a track now widely regarded as one of the first pop songs to use Eastern scales, Paul played it over and over at the apartment of John Dunbar and Marianne Faithfull, and when he saw Ray’s brother Dave at the Scotch, he reputedly joked, “That ‘See My Friend.’ I really like that. I should have written it,” to which Dave retorted, “Well, you didn’t. You can’t do everything.” Ray Davies later commented, “Paul McCartney was one of the most competitive people I’ve ever met. Lennon wasn’t. He just thought everyone else was shit.”

The Kinks often didn’t get the recognition they deserved, and the Beatles didn’t lavish praise on them in interviews in the same way that they did when speaking of the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Who, the Beach Boys, and the Byrds. The only complimentary mention of them I could find by the Beatles was when George said, “I think Ray Davies and the Beatles have plenty in common.” The Kinks had pioneered the use not only of the drone-like sound in pop but also of the distorted guitar (“You Really Got Me”) and social satire (in “Dedicated Follow of Fashion” and “A Well Respected Man”) that paved the way for songs like “Doctor Robert.” Ray Davies was sporting a mustache in April 1966, a good half year before the Beatles appeared to start the trend. Interviewed in 1988 Davies was asked what it was like being in a group in the 1960s. “It was incredible,” he said. “The Beatles were waiting for the next Kinks album while the Who were waiting for the next Beatles record.”

Melody Maker was far more positive and understanding of the LP and noted that “only a handful of the 14 tracks are really Beatle tracks. Most are Paul tracks, John tracks, George tracks, or in the case of ‘Yellow Submarine,’ Ringo’s track.” The review struggled to find appropriate critical language—“I’m Only Sleeping” was “mid-tempo with intriguing harmonies,” “And Your Bird Can Sing” was “beaty mid-tempo with another fine Lennon lead,” and “I Want to Tell You” was “a touch of the bitonalities with a piano figure which resolves into tune for nicely spread harmonies”—but it acknowledged that huge steps had been taken and that pop would never be quite the same again.

The review concluded, “Rubber Soul showed that the Beatles were bursting the bounds of the three-guitar-drums instrumentation, a formula which was, for the purposes of accompaniment and projection of their songs, almost spent. Revolver is confirmation of this. They’ll never be able to copy this. Neither will the Beatles be able to reproduce a tenth of this material on a live performance. But who cares? Let John, Paul, George and Ringo worry about that when the time comes. Meanwhile it is a brilliant album which underlines once and for all that the Beatles have definitely broken the bounds of what we used to call pop.”

Perhaps the most sympathetic review in Britain was published in the Gramophone, a serious monthly magazine largely devoted to classical music. Peter Clayton, a thirty-nine-year-old jazz critic, wrote,

This really is an astonishing collection, and listening to it you realise that the distance the four odd young men have travelled since “Love Me Do” in 1962 is musically even greater than it is materially. It isn’t easy to describe what’s here, since much of it involves things that are either new to pop music or which are being properly applied for the first time, and which can’t be helpfully compared with anything. In fact, the impression you get is not of any one sound or flavour, but simply of smoking hot newness with plenty of flaws and imperfections but fresh. . . . [I]f there’s anything wrong with the record at all it is that such a diet of newness might give the ordinary pop-picker indigestion.

The younger American writers that Crawdaddy had anticipated got it immediately, even though the Capitol version lacked “Doctor Robert,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” and “I’m Only Sleeping,” which had come out earlier on Yesterday and Today. Jules Siegel, a Hunter College graduate in philosophy and English, compared the Beatles to John Donne, Milton, and Shakespeare and said their fate was now “in the hands of those who someday will prepare the poetry textbooks of the future, in which songs of unrequited love and psychedelic philosophy will appear stripped of their music, raw material for doctoral dissertations.” Richard Goldstein, a recent graduate of the Columbia School of Journalism in New York who thought Revolver was “revolutionary” astutely observed in the Village Voice that “it seems now that we will view this album in retrospect as a key work in the development of rock ’n’ roll into an artistic pursuit.”

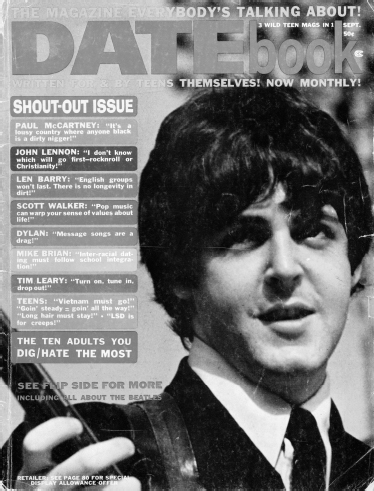

Just as Epstein settled into his vacation home in Wales, events were taking place in America that would profoundly affect his own future and that of the Beatles. The edition of Datebook containing the interviews with John and Paul that Maureen Cleave had carried out earlier in the year had now been printed. The theme of the “shout-out” issue was controversial statements on hot issues such as interracial dating, long hair, drugs, sex, and the war in Vietnam. The only alteration to the text as it had appeared in the Evening Standard was the excision of most of the first two paragraphs of preamble in order to lead with the punchier opening of “When John Lennon’s Rolls Royce, with its black wheels and its black windows, goes past, people say: ‘It’s the Queen,’ or ‘It’s the Beatles.’” A color photo of Paul was on the cover next to two quotes from the interviews that editor Art Unger thought were sufficiently controversial: “PAUL MCCARTNEY: It’s a lousy country where anyone black is a dirty nigger.” “JOHN LENNON: I don’t know which will go first—rocknroll or Christianity.” John’s quote was used again in the feature’s headline. A photo of him on a yacht shielding his eyes from the sun and gazing toward the horizon was prophetically captioned “John Lennon sights controversy and sets sail directly towards it. That’s the way he likes to live!”

John’s comments on Jesus and Christianity were featured in the September 1966 issue of Datebook.

Datebook

Unger wanted the stories to stir up some trouble, and so ahead of the August date when the publications were due out on the newsstands, he mailed copies to some of the most outspoken DJs in the South hoping to get an incensed reaction. In an unpublished memoir he wrote that he did it “figuring that if one story didn’t catch their eyes, the other would.” It had the desired effect. Tommy Charles and Doug Layton, two DJs from Birmingham, Alabama, were aroused enough to begin berating the Beatles on air for their arrogance.

It wasn’t Paul’s critical comment about racism in America that drew their ire but John’s comparison of rock ’n’ roll with Christianity and his claim that that Beatles were now more popular than Jesus. Neither Charles nor Layton was particularly religious (“We went to church but not with any degree of regularity,” Layton later admitted to me), but they knew the sort of issues that stirred listeners and got the station phones ringing. Charles in particular had a reputation for lighting the blue touchpaper and then standing back to watch the explosion, although usually it was over local politics, and so the biggest target in view was City Hall.

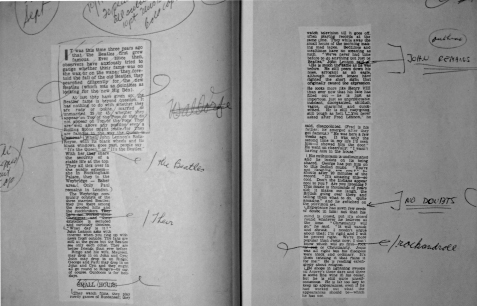

Art Unger’s edit of Maureen Cleave’s Evening Standard interview with John Lennon.

Arthur Unger Papers, State Historical Society of Missouri at Columbia

There was a mood building among conservative Americans that the Beatles had been in the spotlight too long, and they were longing for their predicted decline in popularity. They were just waiting for them to make a wrong move or be pushed out of the way by a newer phenomenon. At this stage the public didn’t know about the group’s fornicating, swearing, and drug taking and not much about their working-class socialist views, but nevertheless there was a strong suspicion that they were a threat to decent values and were leading a generation astray.

When the Beatles had appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show two years previously, the evangelist Billy Graham had said, based on hope rather than hard evidence, that they were likely to be a short-lived craze. Youth preacher David A. Noebel had made a name for himself by writing books and pamphlets with titles such as Communism, Hypnotism & the Beatles (1965) and Rhythm, Riots and Revolution (1966) where he portrayed the Beatles as destroying the morals of the young and thus preparing the West for a Marxist takeover orchestrated by Moscow.

Preacher David Noebel saw rock ’n’ roll as part of a communist plot to undermine the morality of Western youth.

Steve Turner Collection

Layton and Charles had a daily breakfast show on WAQY in Birmingham, and on Friday, July 29, they started discussing what John had said, trying to ignite a debate. According to Layton, it was Charles who picked up the magazine and said something like “Did you hear what John Lennon said?” Layton hadn’t, and so Charles obligingly read out the quotes from Datebook and added, “That’s it for me. I’m not going to play the Beatles anymore.” It was an off-the-cuff remark. Nothing had been planned, but Charles knew that it would play to the prejudices of the Bible Belt audience that listened to morning radio between six and nine.

Although Datebook wasn’t even on the stands yet, the comments triggered an unprecedented number of calls, alerting the DJs to the fact that they’d touched a nerve. They took a snap poll of their listeners and found 99 percent of them shared their disapproval of John’s apparent arrogance. They then suggested it would be a good idea if fans brought in their unwanted Beatles records so that WAQY could organize a huge bonfire when the Beatles next came to the area. As it happened, they weren’t due to play Birmingham on the next American tour but were scheduled to play 240 miles away in Memphis on August 19. What had started as no more than a rash statement to goad listeners was turning into a campaign with its own uncontrollable momentum.

The program director, Frank Giardina (who was also an announcer under the name Frank Lewis), was horrified at what he was hearing. He knew that the records of the Beatles played a vital role in attracting a valuable teenage audience. WAQY was, after all, in the business of Top 40 radio, and as a thousand-watt station up against two far more powerful local stations it could ill afford to lose young fans that tuned in while dressing, having breakfast, and being driven to school. But as Layton and Charles also owned the station, Giardina had little influence in the matter.

These events would probably have remained in Birmingham if twenty-six-year-old Al Benn, the Birmingham bureau manager of United Press International (UPI), hadn’t been driving in the city that morning with his car radio on. The DJs he was listening to were well known to him, and his reporter’s instinct told him that this threat to make a bonfire of the Beatles records was a story in the making. If he filed it to UPI, it would almost certainly get picked up by papers in Atlanta and, soon after, by New York. Little did he know that this would turn into the scoop of his lifetime, a story that immediately ran around the world and later became so much a part of history that people would need only to hear the phrase “more popular than Jesus” to be reminded of the story.

In an article titled “Birmingham Disc Jockeys to Hold Beatles Burning,” UPI reported: “Two local disc jockeys, angered at recent disparaging remarks about Christianity by the ‘Beatles,’ Saturday announced their plans to hold a ‘Beatle burning.’ Tommy Charles and Doug Layton of WAQY said they have asked listeners to send in Beatle records, pictures and clothing for a Beatle bonfire in a couple of weeks.” Charles thought the ban on the Beatles he had introduced two days ago might show the British group that they were “not the godlike creatures” they appeared to think they were. “It’s a shame because they’re talented boys,” he was quoted as saying. “They are as good as or better than any group today but we think it’s time somebody stood up to them and told them to shut up.”

The story ran in papers on Sunday, July 31. When Art Unger heard about it, he immediately called Brian Epstein in Portmeirion to say, “This is getting a little out of hand here. They’re planning to burn Beatles’ records.” Initially, Epstein wasn’t bothered. “Arthur,” he said, “if they burn Beatles records, they’ve got to buy them first.”

But Epstein had seriously underestimated both the instinct of the religious to protect what they consider sacred and the power of the media to stir up controversy and then feed on its own frenzy.