I think that everybody is entitled to an opinion, including entertainers. Entertainers most of all.

—JOHN, 1966

For a few days the Beatles and Brian Epstein remained unconcerned about the hostility building in America. Epstein was still recuperating in the sea air with George Martin as his houseguest; George and Pattie had driven down to Stoodleigh in Devon to stay with Pattie’s mother, Diana, on her farm; and John and Ringo were spending time with their families in Weybridge. On July 30, at Wembley Stadium in London, England’s soccer team had dramatically triumphed over West Germany in extra time to win the FIFA World Cup for the first (and so far only) time, unleashing a booster dose of good feelings in a nation that was just getting used to being vital, trendy, and swinging. “Good Day Sunshine” captured the mood of the day, and the best of the British summer still lay ahead.

On August 1, Paul went to BBC’s Broadcasting House to be interviewed for David Frost’s new radio series David Frost at the Phonograph. It was a fairly light conversation, but an interesting exchange took place when Paul spoke of the creative restlessness that always kept him searching for the next breakthrough. Frost asked him if he was ever completely satisfied with a Beatles record once it had been made. “No, that’s the trouble. Immediately we’ve done an LP, we want to do a new one, because we’re a bit fed up. And the time it takes a record company to get it out, by the time it’s out, we really hate most of the tracks. That’s the way it is.” Frost wanted to know in that case whether any Beatles record still felt satisfying to him. “No. I go off records because . . . we’re developing,” he said, adding that two years ago their songs were in his opinion “a bit cornier,” and, for that reason, “I suppose I go off records a bit quicker than anyone else would.”

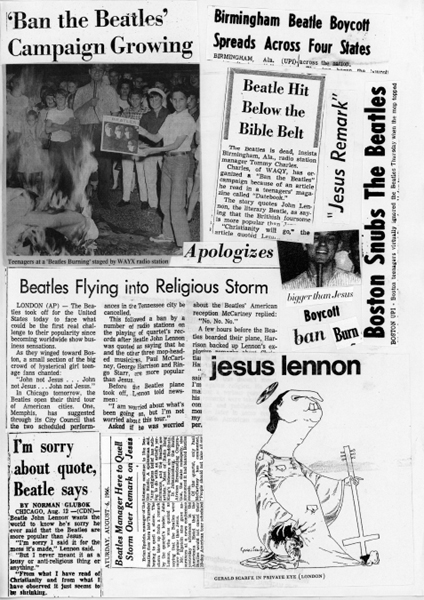

The same day, in a follow-up story titled “Hot Time Is Scheduled for Beatles,” Al Benn revealed that the threatened bonfire of Beatles paraphernalia was scheduled for mid-August in Birmingham, Alabama. From August 2 onward, at the top of every hour, Layton and Charles made spot announcements advertising the planned immolation and listing collection points where fans could bring their records, posters, pictures, and books. WAQY would arrange for the materials to be collected and stored, ready for the day of destruction.

Other news agencies, notably the Associated Press, had now picked up on the story, and, as it spread, radio stations around the country began to echo the rabble-rousing rhetoric of Layton and Charles. By August 4, “Lennon Says Beatles More Popular Than Jesus” had become a nationwide story. An AP release that day bore the headline “Broadcasters Hit Beatles” and reported on more planned record burnings. It repeated John’s statement and then quoted Tommy Charles: “We just felt it was so absurd and sacrilegious that something ought to be done to show them they cannot get away with this sort of thing.”

Only a small number of stations had issued outright bans so far—maybe as few as forty—all of them inspired by what had happened in Birmingham, and many of them not stations that normally played a lot of Beatles music anyway. The Maureen Cleave interviews with all four Beatles (worked together as a single piece over five pages) had already appeared in the New York Times Magazine on July 3 under the title “Old Beatles—A Study in Paradox” and even though John’s soon-to-be controversial quote had been included, it hadn’t provoked comment. It even had an additional quote—“Show business belongs to the Jews. It belongs to their religion”—that likewise failed to draw any indignation. Newsweek (circulation two million) had used John’s words in its March 21 issue, and in May the interview had appeared in Detroit magazine. Again, no records were burned as a result, and John’s comment didn’t even become a talking point.

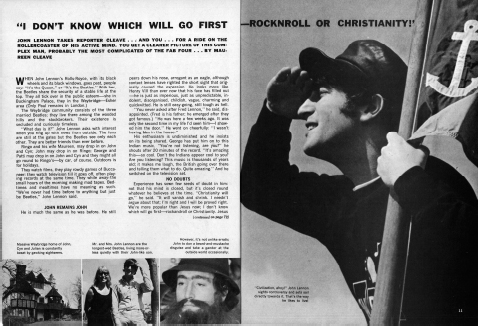

John’s casual comment about Jesus heightened security fears when the Beatles toured America.

Steve Turner Collection

Although the record-burning, Beatle-banning campaign was an exercise in manipulation by the media and much of the outrage was either exaggerated or fake, it had real-life consequences. Datebook became inundated with calls—from fans wanting to know whether John had really said what he was quoted as saying, from radio stations requesting quotes from editor Art Unger, and from magazines like Newsweek requesting advance copies. Fred Forest of WMOC in Chattanooga called to get John’s comments clarified, and when Datebook’s message taker asked him to describe the reaction in Tennessee, Forest responded, “The Beatles better watch out when they hit the Southern States.” The message taker added a personal note: “Forest is apparently not a Bible thumper. He was just quoting from general public reaction.” Christie Barter, a press officer from Capitol Records overseeing the East Coast, called to express concern that sales of Beatles records could be affected if DJs continued to announce bans.

Nat Weiss, Epstein’s business partner in New York; Sid Bernstein of the booking agency General Artists Corporation; and Epstein’s American entertainment attorney Walter Hofer phoned Epstein in Portmeirion to update him about the buildup in America, recommending that, despite his illness, he fly to America as soon as possible to organize some damage control. In his view, if John didn’t explain himself to the satisfaction of the Christian constituency in the South, the danger was that some promoters might cancel their concerts out of fear of violence either toward themselves or toward the Beatles. Brian suggested John should go to the studio with George Martin to record an apology scripted by former journalist Derek Taylor (ghost writer of Epstein’s autobiography A Cellarful of Noise and now West Coast PR man for the Byrds and the Beach Boys) that could be released to US radio stations.

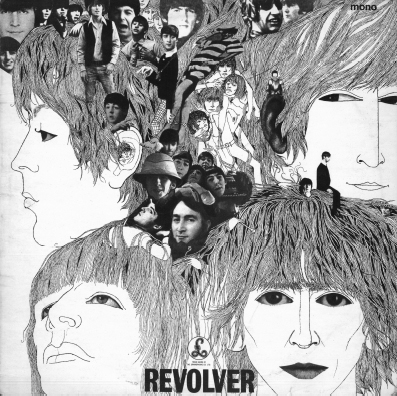

The cover of Revolver as released in Britain, August 1966.

Steve Turner Collection

Epstein was driven from Portmeirion to Chester, where he took a chartered four-seater Cessna plane to London and then a scheduled Pan Am flight on to New York. Weiss met him at the airport. That day’s papers carried the news that the satirical comic Lenny Bruce—the man famous for lines such as “People are straying away from the church and going back to God”—had died in his Hollywood home of a heroin overdose. The next morning (August 5, the day of Revolver’s release in the UK) Epstein woke up to find the John and Jesus story on the front page of the New York Times. A press conference was hurriedly arranged for that afternoon at the Americana Hotel on Seventh Avenue.

The New York Times splash was a UPI story about the continuing wave of Beatles record bans with a quote from Maureen Cleave that was typically intelligent and succinct. “[John] was simply observing that so weak was the state of Christianity that the Beatles were, to many people, better known than Jesus,” she said. “He was deploring rather than approving this. He said things had reached a ridiculous state of affairs when human beings could be worshiped in this extraordinary way.”

In another interview, with DJ Clark Race of KDKA (Pittsburgh), Cleave said that the comments had been “taken out of context and did not accurately reflect the article or the subject as it was discussed.” She said that John’s intention was to say that “the power of Christianity was on the decline in the modern world and that things had reached such a ridiculous state that human beings (such as the Beatles) could be worshipped more religiously by people than their own religion.” These comments were scooped up by Capitol and used as the basis of a press release headed “Author of Beatles Article Denies Quote Attributed to Lennon.”

Epstein arrived at the Americana looking subdued, wearing a dark suit with an appropriately dark tie. Two further stories had appeared in print that day which made matters worse, and he was not happy that Maureen Cleave was sharing her thoughts with other news outlets. An extract from Paul’s interview with David Frost had been released ahead of its transmission. In it Paul had said that Americans “seem to believe that money is everything. This applies especially to the sort of people that we meet—agents and corporation people. You get the feeling that everybody’s after money, and it’s frightening.” George had also been outspoken. Speaking to Disc and Music Echo shortly after getting back from the Far East and before the Jesus controversy had blown up, he made the comment, “We’ll take a couple of weeks to recuperate before we go and get beaten up by the Americans.”

Epstein was furious. Although these statements were not as controversial as what John had said, it wasn’t good at this time for any of the Beatles to appear to be anti-American as well as anti-Christian. Epstein immediately sent a telegram to his assistant Wendy Hanson in London instructing her to clamp down on any loose talk. “Please advise Beatles to continue not to speak to the press under any circumstances,” he wrote. “Also, it is not necessary for John to make the [apology] tape with Martin. Please advise Maureen Cleave.”

When Epstein stood up before the gathered journalists and photographers at the Americana, he spoke clearly and assuredly but was conscious that he had to choose his words carefully, because the wrong verb or adjective could overheat an already tense situation. He stepped up before the phalanx of microphones, adjusted his papers, and then delivered his prepared statement on behalf of John.

The only reason I’m here, actually, is in an attempt to clarify the situation, the general furor that has arisen here, and I have prepared a statement which I will read which has had John Lennon’s absolute approval this afternoon with myself by telephone. This is as follows: The quote which John Lennon made to a London columnist more than three months ago has been quoted and represented entirely out of context. Lennon is deeply interested in religion and was, at the time, having serious talks with Maureen Cleave, who is both a friend of the Beatles and a representative for the London Evening Standard. Their talks were concerning religion.

What he said, and meant, was that he was astonished that in the last 50 years the church in England, and therefore Christ, had suffered a decline in interest. He did not mean to boast about the Beatles’ fame. He meant to point out that the Beatles’ effect appeared to him to be a more immediate one upon, certainly, the younger generation. The article, which in depth was highly complimentary to Lennon as a person, was understood by him and myself to be exclusive to the Evening Standard. It was not anticipated that it would be displayed out of context and in such a manner as it was in an American teen-age magazine.

In the circumstances, John is deeply concerned, and regrets that people with certain religious beliefs should have been offended in any way whatsoever.

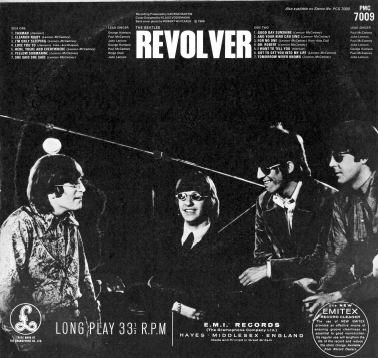

The back cover of Revolver as released in Britain, showing the track listing and a photo of the Beatles taken while filming promotional sequences for “Paperback Writer” and “Rain” at EMI Studios.

Steve Turner Collection

What Epstein did not appear to have been aware of—or chose to ignore—was that his employee Tony Barrow had offered the interview to Datebook on March 5 (the day after it was first published) in a letter that Art Unger kept in his files. Written on NEMS Enterprises Ltd. letterhead stationery and sent to Unger at Datebook’s office at 71 Washington Place in New York, it read:

Dear Art,

I haven’t any positive information for you just yet regarding your proposed visit to London. In the meantime, I think you might be more than interested in a series of “in-depth” pieces which Maureen Cleave is doing on each Beatle for the London Evening Standard. I’m enclosing a clipping showing her piece on John Lennon. I think the style and content is very much in line with the sort of thing DATEBOOK likes to use.

I have told Maureen I am writing to you on this and, in fact, I think she would be quite willing to do a re-write job on the full series specifically for DATEBOOK.

Perhaps you could get together with her when you’re in London. If you have more urgent interest in the material I’ll ask her to drop you a line in the meantime. Let me know.

With good wishes,

Yours sincerely,

for NEMS ENTERPRISES LTD

TONY BARROW

Senior Press and Publicity Officer.

Beginning March 10, Unger and Cleave exchanged correspondence that resulted in Datebook buying rights from the United Feature Syndicate on March 31. Unger confirmed the purchase with Barrow on April 4 and asked whether “you or the boys felt there was any distortion in the material since there is still time to cut or correct in case of factual error etc.” Barrow responded on April 14 saying, “I am glad to hear that you managed to secure the magazine rights for the Maureen Cleave series.” He didn’t take up the invitation to make any changes.

After his speech, Epstein opened himself up to questions. A lot of the writers pursued rumors that the American concerts were not selling as well as expected. There was speculation that this apparent flagging interest might signal the beginning of the end. “This is the third time that the Beatles have been to the United States and quite obviously they’re not the novelty they were in the first place,” Epstein conceded.

Someone wanted to know how they felt having gone from being objects of adulation to objects of resentment, hostility, and derision. “They feel absolutely terrible,” he admitted, adding that it was worrying for them to be pushed around and face antagonism. “The business of coming out of Manila was something that they and I will never forget. It was very unpleasant.”

Another journalist asked if any tour dates would be altered to avoid the Bible Belt cities where protests were taking place. “This is highly unlikely,” Epstein said. “I’ve spoken to many of the promoters this morning and when I leave here I have a meeting with several of the promoters who are anxious that none of the concerts should be cancelled. Actually, if any of the promoters were so concerned and it was their wish that a concert should be cancelled I wouldn’t in fact stand in their way. As a matter of fact, the Memphis concert which is nearest to the place where this broke out apparently sold more tickets yesterday than they had done up until that day.”

The issue of sluggish sales resurfaced. “This has been exaggerated because I’ve been through the figures for many of the concerts and they are good as could possibly have been expected. In fact, in many areas they are complete sell-outs and you must remember that the Beatles are not doing ordinary concerts. They are playing in enormous auditoriums and stadiums.”

At this point Art Unger stood up to defend the integrity of Datebook. “I believe John had a perfect right to say what he did say and I think that it’s objectionable to deny him the right to say what he believes,” he said. “However, that has nothing to do with the fact that the story that Maureen Cleave wrote appeared not out of context in Datebook. All of the quotes are there. The entire story is there.”

Epstein looked slightly taken aback. “It did appear out of context,” he asserted. “This was taken as the predominant part of the article, which it wasn’t. Anyway, I could go on discussing that with you at great length. It is very definitely my view, and practically everybody else’s view, that it was out of context.”

It was unclear whether Epstein thought the whole article was out of context by being placed in Datebook (having initially been produced for an adult readership in London) or whether he thought that the quote on Christianity was out of context on the front cover. It’s true it wasn’t representative of the entire interview, but no single quote would have been. In America, it was certainly the one thing he said most likely to gain traction.

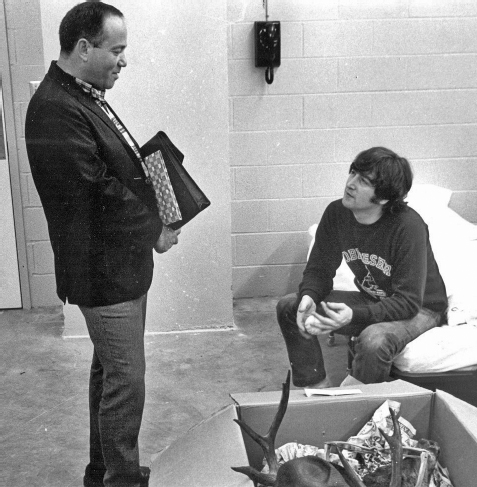

During the Beatles’ 1965 tour of America, John spent time backstage with Datebook editor Art Unger.

Raul Nuñez

“What about future interviews?” someone asked. “Will the Beatles be a bit more careful or a bit more selective in who they do stuff with?” Epstein thought carefully before saying, “The Beatles are basically very honest people. Naturally as one goes on in this business one learns and it is unfortunate that this quote and this article appeared in a teen-age magazine and was open to so much misinterpretation. When it originally appeared in the Evening Standard in London nothing happened at all. As a matter of fact, there were four articles, one on each of the boys, and they were all thought to be of the very best and highest standard. Maureen Cleave is an excellent columnist.”

Q: What is Mr. Lennon’s reaction to the furor?

EPSTEIN: He is very genuinely and truly concerned.

Q: Do any of the Beatles have any formal religious affiliation?

EPSTEIN: No.

Q: Mr. Epstein, could you say that this was implicitly a criticism of the Church of England since that is the official state church in England.

EPSTEIN: No. It’s not an official criticism of any kind. It was a comment that was incidental.

Q: Are they definitely still coming to the States?

EPSTEIN: They will arrive in Chicago on August 11—where the concerts are sold out. I believe there are about 100 seats to go.

Q: Brian. Are you worried in any way what might happen to the Beatles when they arrive?

EPSTEIN: Yes. I am concerned.

Q: What about?

EPSTEIN: Security.

Q: What do you propose to do?

EPSTEIN: There is very little that you can do because they have always enjoyed maximum security in this country and the tours have been exceptionally well arranged and one just hopes for the best.

Q: Are you worried because of things that have happened in places like Austin and Chicago? [This was a reference to Richard Speck’s knifing of eight student nurses in Chicago on July 14 and Charles Whitman’s shooting spree from the University of Texas tower in Austin, where he hit forty-three people, killing thirteen of them, the first mass murder in a public place that America had ever experienced.]

EPSTEIN: Not specifically, because this sort of thing has happened before previous tours.

Q: Are you taking any special precautions?

EPSTEIN: No. But I shall watch the security personally, very much.

The Beatles left London Airport on August 11 on a Pan Am flight bound for Boston. On arrival they were greeted by up to six hundred screaming fans. A connecting flight took them to Chicago, where they disembarked ahead of the rest of the passengers close to a hangar away from the main terminal. From here they were driven straight to the Astor Tower Hotel, which was two blocks from Lake Michigan. Tony Barrow had arranged a press conference in his suite on the twenty-seventh floor for local and national journalists at which he hoped the Beatles, and John in particular, would explain themselves sufficiently well to defuse the situation.

Art Unger had a private meeting with Brian Epstein in his penthouse suite. The Beatles’ manager appeared to be in a good mood. He was dressed in tight white corduroy trousers and a flowing lavender shirt, and he offered Unger a drink. But his mood soon changed. Unger was an accredited member of the press corps that would be following the Beatles to every venue, attending every concert, taking part in conferences and round table interviews, and flying on the group’s chartered planes and buses. Epstein wanted him to “voluntarily” surrender his pass. He thought that being a visible presence on the tour might lead some critics to suspect that the whole controversy had been a publicity stunt engineered by Datebook and NEMS to put the tour on the front pages and sell tickets.

“It was a bad idea for you to run those interviews in the first place,” he told him. “But if you agree to cancel your participation, there are many other things I could do for you. We could make a great publishing team.” In his private notes Unger recorded, “I resisted the temptation to tell him that his own publicist had sent me the stories in the first place. I never revealed that to anybody because I didn’t want to place the burden on a nice guy who had only been doing his job.”

He was angry that Epstein was trying to bribe him, although he didn’t believe he would actually go as far as to have him banned. “Brian,” he said. “I came here to cover the tour and I’m going to cover it. If you don’t want me to come you’ll have to throw me out of the press corps and you know how the other press people will react.” Unger left the room but remained on the tour. When he told John what had taken place, John was angry. “Don’t you worry,” he said. “You’re coming with us. I’ll tell Brian that if you don’t go, I won’t go.”

There was a select group of journalists and DJs with the precious red passes that allowed them total tour access as well as seats on the buses and charter planes that ferried the Beatles between cities. Besides Unger there was Judith Sims, founding editor of TeenSet, English journalist Bess Coleman from Teen Life, Marilyn Doerfler from Hearst Newspapers, and the DJs Ken Douglas (WKLO Louisiana), Jerry Ghan (WKYC Cleveland), Paul Drew (WQXI Atlanta), Jim Stagg (WCFL Chicago), Scott Regan (WKNR Detroit), George Klein (WHBQ Memphis), Tim Hudson (KFWB Los Angeles), Kenny Everett (Radio London), Ron O’Quinn (Radio England), and Jerry Leighton (Radio Caroline North). Other writers and DJs joined the tour only for one or two dates, usually concerts immediately preceding ones in their home city.

Before going into the suite for the press conference, Epstein and Barrow took John aside and briefed him. They again explained that he needed to reassure the Americans that he was neither attacking Christianity nor suggesting that the Beatles were divine. He had simply meant to compare the passion and interest surrounding the group with the same generation’s apparent loss of interest in formal religion.

John was torn. One the one hand he didn’t want to risk wrecking the popularity of the Beatles and everything he had ever worked for, but on the other he didn’t want to be insincere or water down his opinions. People valued the Beatles’ irreverence, honesty, and challenging comments. He didn’t want to compromise his views and turn into the sort of bland entertainer he had so often derided as being “soft.” During the 1965 tour of America he had told a reporter from Datebook, “I’ve reached the point in my life when I can only say what I feel is honest. I can’t say something just because it’s what some people want to hear. I couldn’t live with myself.”

“He was terrified,” Cynthia Lennon told me in 2005. “What he’d said had affected the whole group. Their popularity was under the microscope but he was the one who had opened his mouth and put his foot in it. I didn’t go on the tour with him but I know he was very frightened.”

John knew that there had been letters from anonymous sources threatening violence, and there were worries that white supremacists in the South could plant a sniper at one of the concerts. It upset him that something he had said could make his best friends Paul, George, and Ringo vulnerable to an attack. After listening to the options of what he could say and do he put his head in his hands and began weeping in front of Epstein, Barrow, and photographer Harry Benson. None of them had ever seen him so broken. “He was trying, but not actually succeeding, in hiding it from us,” Tony Barrow told me. “It was so uncharacteristic of the guy.”

The main room of Barrow’s suite was a small space for such a major press conference. So many journalists were squeezed in that the Beatles were clustered together with their backs against a wall. To reassure outraged America that they were reasonable and responsible they wore the dark suits, white shirts, and neckties they’d worn on previous tours rather than the cool Chelsea fashions. John was chewing gum to calm his nerves.

The first questioner asked John to clarify the Datebook remarks. “If I had said ‘television’ is more popular than Jesus, I might have got away with it,” he answered. “But as I just happened to be talking to a friend, I used the word ‘Beatles’ as a remote thing—not as what I think of as Beatles—as those other Beatles like other people see us. I just said ‘they’ are having more influence on kids and things than anything else, including Jesus. But I said it in that way, which is the wrong way.”

What did he think when he heard that some teenagers agreed with him—that they did love the Beatles more than Jesus? “Well, originally I was pointing out that fact in reference to England—that we meant more to kids than Jesus did, or religion, at that time. I wasn’t knocking it or putting it down, I was just saying it as a fact. It is true, especially more for England than here. I’m not saying that we’re better, or greater, or comparing us with Jesus Christ as a person or God as a thing or whatever it is. I just said what I said and it was wrong, or was taken wrong. And now it’s all this.”

He admitted that the burnings and the bans bothered him, but he was pressed further to make a statement as to whether he felt any regret over having made the comment. “I am. Yes, you know. Even though I never meant what people think I meant by it, I’m still sorry I opened my mouth.”

Some journalists seemed to think that this fell short of a full apology. One asked, “Did you mean that the Beatles are more popular than Christ?” John sighed before answering, rattled that after all he’d said through Brian and now in person the discussion hadn’t moved on: “When I was talking about it, it was very close and intimate with this person that I know who happens to be a reporter. And I was using expressions on things that I’d just read and derived about Christianity. Only I was saying it in the simplest form that I know, which is the natural way I talk. But she took them, and people that know me took them exactly as it was—because they know that’s how I talk.”

The conversation then turned to the music. Writers found it difficult to reconcile the mop tops of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” with the serious-minded musicians behind “Eleanor Rigby” and “Tomorrow Never Knows.” Paul picked up the question, relieved that the conversation appeared to have moved away from the controversy. “The thing is,” he said, “we’re just trying to move it in a forward direction. And this is why we’re getting in all these messes with saying things—because we’re just trying to move forwards. People seem to be trying to sort of hold us back and not want us to say anything that’s vaguely inflammatory. I mean, if people don’t want that, then we won’t do it. We’ll just sort of do it privately. But I think it’s better for everyone if we’re just honest about the whole thing.”

This was Paul doing what he did best—ameliorating potentially explosive confrontations. He was eager on the one hand to assert the group’s commitment to progressive art and attitudes but concerned on the other not to cause unnecessary offense. He implied that the Beatles’ only motivation was honesty but offered to compromise by only being honest “privately” if that’s what it took to avoid causing upset. Thus, in the most charming way possible, he placed the Beatles on the higher moral ground without accusing or denigrating their antagonists.

The next day the group faced another press interrogation, this time from DJs and some accredited journalists on part of the tour. John repeated his position on the Datebook affair but went into more depth: “My views on Christianity,” he explained, “are directly influenced by The Passover Plot by Hugh J. Schonfield. The premise is that Jesus’ message had been garbled by his disciples and twisted for a variety of self-serving reasons by those who followed, to the point where it has lost validity for many in the modern age. The passage that caused all the trouble was part of a long profile Maureen Cleave was doing for the London Evening Standard. Then, the mere fact that it was in Datebook changed its meaning that much more.”

Maureen Cleave’s interview with John as it appeared in Datebook.

Datebook

Asked what his religious background was, he explained,

Normal Church of England—Sunday school, and church. But there was actually nothing going on in the church I went to. Nothing really touched us. . . . By the time I was nineteen, I was cynical about religion and never even considered the goings-on in Christianity. It’s only the last two years that I, all the Beatles, have started looking for something else. We live in a moving hothouse. We’ve been mushroom-grown, forced to grow up a bit quick, like having thirty- to forty-year-old heads in twenty-year-old bodies. We had to develop more sides, more attitudes. If you’re a bus man, you usually have a bus man’s attitude. But we had to be more than four mopheads up there on stage. We had to grow up or we’d be swamped.

Q: “Mr. Lennon, do you believe in God?

JOHN: I believe in God, but not as one thing, not as an old man in the sky. I believe what people call God is something in all of us. I believe that what Jesus, Mohammed, Buddha, and all the rest said was right. It’s just the translations have gone wrong.

As with the first conference, there were questions about whether the Beatles’ popularity was slipping. A UPI story had mentioned that shares of Northern Songs (the publisher of the Beatles’ songs) had dropped from $1.64 to $1.36 since the scandal. The latest single, “Eleanor Rigby” / “Yellow Submarine” (like “Paperback Writer” before it), had not gone straight to No. 1 in the United Kingdom. “Love Letters” (Elvis Presley), “Mama” (Dave Berry), “God Only Knows” (Beach Boys), “Black Is Black” (Los Bravos), “The More I See You” (Chris Montez), “Out of Time” (Chris Farlowe), and “With a Girl Like You” (The Troggs) had held it back from the top spot. Unbelievably, there were still tickets available for the American tour.

Q: Do you feel you are slipping?

JOHN: We don’t feel we’re slipping. Our music’s better, our sales might be less, so in our view we’re not slipping, you know.

Q: How many years do you think you can go on? Have you thought about that?

GEORGE: It doesn’t matter, you know.

PAUL: We just try and go forward.

GEORGE: The thing is, if we do slip it doesn’t matter. You know, I mean, so what—we slip and so we’re not popular anymore so we’ll be unpopular, won’t we? You know, we’ll be like we were before, maybe.

JOHN: And we can’t invent a new gimmick to keep us going like people imagine we do.

Q: Do you think this current controversy is hurting your career?

JOHN: It’s not helping it. I don’t know about hurting it. You can’t tell if a thing’s hurt a career or something until months after, really.

For the two shows (3:00, 7:30) at the International Amphitheatre on South Halsted in Chicago the Beatles stuck to the eleven-song set they’d used in Germany, Tokyo, and Manila with the exception of performing Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally” as the closer rather than “I’m Down.” They played nothing from the newly released Revolver, because so many of the songs depended on other instruments (“Got to Get You Into My Life,” “Eleanor Rigby,” “Love You To,” “For No One”) or studio trickery (“Tomorrow Never Knows,” “I’m Only Sleeping,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” “She Said She Said”). The equipment of the day didn’t permit them to do it.

The same four American acts supported them during the whole tour: black R & B singer Bobby Hebb, who’d had a recent hit with the single “Sunny”; East Coast girl group the Ronettes (with Ronnie Spector temporarily replaced by her cousin Elaine Mayes because her husband, Phil Spector, didn’t trust her on the road with the Beatles); Boston garage band the Remains (who did their own set but also played behind Hebb and the Ronettes); and the Cyrkle, a Pennsylvania band managed by Epstein and Nat Weiss.

Chicago didn’t sell out in the way that Epstein had predicted (although there were around twelve thousand fans for each concert), but at least there had been no trouble. Fans waved supportive banners declaring SAY WHAT YOU THINK JOHN and WE LUV YOU MORE THAN EVER. The next morning the Beatles flew into Detroit for another two shows, again not sold out, at the Olympia Stadium on Grand River Avenue. This time a sole protester was spotted carrying a placard that said LIMEY GO HOME.

Few people bothered to ask Ringo for his opinions. He wasn’t a composer, didn’t need to fret about the group’s direction, and was a relative latecomer to the lineup (he joined in 1962), but when journalists engaged him, he gave long and thoughtful answers. Asked by one writer whether he’d seen any change in teenagers over the years, he said, “Yes. I think they’re getting a bigger chance to express themselves than ever before, which is good. This has been helped by the likes of Dylan and us. All the stars of the 1920s were men, you know? There were no teenagers. You had to be over 30 before anyone took any notice of you. It’s only over the last ten years or so that anyone under the age of 20 has got anywhere.”

Asked if the Beatles had ever wanted to record soul music, he answered, “We feel the urge but we’ve wised up. We’ve realized that we are white and haven’t got what they’ve got. We haven’t got that thing, so therefore that’s why we called the LP Rubber Soul. In Britain all these groups are playing soul music that has as much soul in it as this tape recorder. No soul at all. And, really, we haven’t got the soul that they have.”

Between the afternoon and evening show in Detroit three journalists were allowed to interview the Beatles in a private office behind the stage. One of them was Loraine Alterman, who wrote a teen column for the Detroit Free Press and would go on to write for Rolling Stone and have John Lennon as best man at her 1977 wedding to actor Peter Boyle. Alterman was a smart and understanding woman who the group found refreshing to talk to after the press conferences, where, as usual, everything but the music was discussed. In her published story she said of the Beatles, “They showed people that pop music can have meaning and its creators can be intelligent, talented artists.”

George, wearing a black shirt and black trousers, sat on a table with his legs tucked under him as he talked to Alterman. “The main hang-up for me is Indian music,” he told her.

Really groovy—to pardon the expression, as opposed to the hip things in Western music which are opposed to Western classical music. Indian music is hip, yet 8,000 years old.

I find it hard to get much of a kick out of Western music—even a lot of Western music I used to be interested in a year ago. Most music is still only surface, not very subtle compared to Indian music. Music in general, including ours, is still on the surface.

We were right for the time when we came out. The pop scene five years ago was definitely looked upon by “musicians” as a dirty word. Pop was just something crummy. Now I think a lot of things in the pop field have more to them. We’re very influenced by others in pop music and others are influenced by us. That’s good. That’s the way life is. You’ve got to be influenced and you try to be influenced by the best.

His growing dissatisfaction with the superficialities of pop was apparent, as was his desire to delve deeper both into the music and the spirituality of India. “I’m far from the goal I want to achieve,” he said. “It will take me 40 years to get there. I’d like to be able to play Indian music as Indian music instead of using Indian music in pop. It takes years of studying, but I’m willing to do that.”

Alterman was worried about talking to John, having heard of his intolerance toward poorly thought-out questions and his wounding wit, but he put her at ease. Regarding the “more popular than Jesus” issue he confessed: “I was shocked out of me mind. I couldn’t believe it. I’m more religious now, and more interested in religion, than I ever was.”

He was vague about his creative process, saying that he just made things up and that “some of it is just whatever comes into my head.” Significantly, he felt that the Beatles had developed from a group that imitated rock ’n’ roll heroes to one with a sound that was distinctively theirs. “It has progressed and gotten more like Beatle music,” he said. “Before, it was more of anyone else’s music. . . . We worked hard [on Revolver] because we wanted everything so perfect. On the Rubber Soul album we found out a lot technically. Things have come into focus. From there we could evolve into Revolver.”

Paul, who Alterman regarded as “the handsomest Beatle of all,” was charming and flirtatious, rubbing his knees against hers and joking with her that she could now sell them to collectors. He explained how his songs (he cited “Eleanor Rigby” and “Yellow Submarine”) tended to come directly from his imagination and were not necessarily based on personal experience or intense feelings. They arose from concepts, words, or characters that entered his mind and seemed to demand investigation by being turned into art. She asked him what he thought the Beatles had done for contemporary pop music. “Given it a bit of common sense,” he said. “A lot of it was just insincere, I think. Five years ago you’d find men of forty recording things without meaning just to make a hit. Most recording artists today really like what they’re doing, and I think you can feel it on the records.”

Another of the three journalists granted time in Detroit was Leroy Aarons of the Washington Post. Aarons, who had covered the Beatles in Washington, DC, in 1964, had been dispatched by his city editor to get something more in depth than was coming out of the press conferences. He was scheduled to do ten minutes with John, but the interview went so well it ended up lasting forty minutes, and he was invited to join the tour until the August 15 date in DC.

Aarons figured that he’d get more out of John by treating him as a serious thinker rather than a mouthy pop star. He talked to him about the recent Time magazine “Is God Dead?” cover story, and John opened up with thoughts about religion, his conventional Anglican upbringing, and the problems of pursuing truth in an industry designed to trade in fantasy. “That’s the trouble with being truthful,” he said. “You try to apply truth talk, although you have to be false sometimes because the whole thing is false in a way, like a game. But you hope sometime that if you’re truthful with somebody they’ll stop all the plastic reaction and be truthful back, and it’ll be worth it but everybody is playing the game and sometimes I’m left naked and truthful with everybody biting me. It’s disappointing.”

Perceptively, Aarons could see that John’s questioning of the faith handed down to him at Sunday school in Woolton, Liverpool, was all part of the adventurous, challenging, and experimental approach that was currently enlivening their music. What he had said to Maureen Cleave was no more than a provisional opinion but emerged from a serious search. “I can’t express myself very well,” John confessed. “That’s my whole trouble.”

When John left to go on stage, Aarons found a desk and composed his story. After the show he joined the Beatles on the bus that took them 170 miles to Cleveland, Ohio, where they were due to give a single concert at the Cleveland Municipal Stadium. They stayed at the thousand-room Sheraton Cleveland and scheduled a press conference for 5:45 in the hotel’s Empire Room.

Aarons had handed them his story to look over—not usual Washington Post practice, but, hey, this was the Beatles—and in the afternoon was summoned to their suite. Tony Barrow told him they were all pleased with the story, but there was one thing they wanted changed. Aarons had commented that the latest single had slipped on the charts, but it hadn’t.

He may have been referring to “Paperback Writer,” which had reached No. 1 on the US charts but was now tumbling down, as would be expected ten weeks after its release, or he may have been talking about “Yellow Submarine,” which was what DJs would call “a slow climber.” It wasn’t slipping down, but neither was it racing up. This sing-along single was a far cry from what young fans expected from the world’s premier rock band. Released on August 8, it was only at 52 on the Billboard charts of August 20, rose to 8 the next week, then 5, then 3, before reaching its highest position of 2 in September.

But 1966 was a year of exceptional pop singles. Records later to be regarded as classics crammed the charts every week. In August alone the following singles were among those in Billboard’s Top Twenty: “Wild Thing” by the Troggs, “Summer in the City” by the Lovin’ Spoonful, “Sunny” by Bobby Hebb, “Over Under Sideways Down” by the Yardbirds, “I Want You” by Bob Dylan, “Mother’s Little Helper” by the Rolling Stones, “Summertime” by Billy Stewart, “Working in the Coal Mine” by Lee Dorsey, “Land of 1000 Dances” by Wilson Pickett, “You Can’t Hurry Love” by the Supremes, and “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” by the Beach Boys. The competition was tough.

Cleveland was the first concert where fans got out of hand. Four songs into the set, Paul mistakenly introduced a song by saying “For our next and final song.” Fans, thinking the group was about to disappear, crashed through the wall separating them from the stage and began clambering up, breaking through the police cordon. The group had to be rushed to safety by helmeted riot officers, and the show was stopped for half an hour until order was restored.

The next afternoon they flew to Washington, DC, where six limousines were waiting at the airport to take them to the Shoreham Hotel on Calvert Street. The Washington Post had Leroy Aarons’s story on its front cover—“ ‘Can’t Express Myself Very Well’: Beatle Apologizes for Remarks.” At the press conference the group was asked whether the Jesus comments had been made in order to sell seats. “That’s not a publicity stunt,” said John. “We don’t need that publicity. Not like that.”

At the DC Stadium on East Capitol Street they played one show for over thirty-two thousand fans before reboarding the bus and driving to Philadelphia. The incidents that they feared might take place hadn’t occurred, and there was no serious opposition from right-wing political groups or religious fundamentalists other than five costumed members of the KKK who paraded incongruously outside the stadium in Washington. After the repeated explanations and apologies from John, the record bans were being lifted. Even the Birmingham burning was called off, leaving WAQY with a basement full of unwanted Beatles paraphernalia that it would have great difficulty in destroying.

American newspapers in 1966 didn’t publish reviews of the concerts in their arts sections but reported on them as news. There was never any mention of the songs that were played or the quality of the performance. The journalists were interested only in the volume of the screams, the views of the teenagers, the size of the audience, and the takings at the box office.

Many of them clearly thought the Beatles were participants in a cynical moneymaking exercise, which is why they couldn’t understand the artistic developments on Revolver. As they saw it, the point of show business, like any other business, was to give people more of what they wanted. The Beatles’ hair and clothes were regarded as gimmicks designed to draw attention.

In some coverage there was disdain for John, who was regarded as someone trying to be too smart for a pop star. He was repeatedly referred to as “the brainy Beatle” or “the literary Beatle,” as though it was unnatural for someone to try to be successful in more than one medium or as though it was improper for someone of intelligence to make a career out of writing and performing pop songs.

On tour the Beatles were trapped, in hotel rooms where the corridors were patrolled by security guards or on buses, planes, limousines, press conferences, airports, and stages surrounded by fences. They could circle the world but saw very little of it. They could talk freely, but had to weigh the consequences of every statement. Donovan, who had contributed a couple of lines to “Yellow Submarine” (“Sky of blue and sea of green”), concluded that the song was indirectly about the shared life of the Beatles—four guys trapped in a constricted space who sang songs to keep up their spirits.

After Philadelphia there were concerts in Toronto (August 17) and Boston (August 18) before the Beatles flew down to Memphis for potentially the most dangerous date of the tour, the first of only two appearances in the South, the region that had been most vociferous in denouncing John for his Datebook comment. Although they weren’t going to be staying overnight (they would fly directly to Cincinnati in the early hours of the next morning), they were assigned eighty-six police officers and twenty private guards. Jerry Foley, the local promoter, had built a seven-foot-high stage at the Mid-South Coliseum with a five-foot wall in front to protect it from invasion.

Ticket sales had dipped in the wake of the protests in early August but picked up afterward. Over twenty-two thousand fans, out of a potential twenty-six thousand, would see the two shows. For the Beatles these were the tensest of all the concerts. Earlier in the day there had been a message that one of them would be assassinated on stage. In the afternoon there were half a dozen members of the Ku Klux Klan parading in their robes outside the venue. Elsewhere in the city, at the Ellis Auditorium, there was a Christian revivalist meeting planned in the hopes that the turnout (estimated at eight thousand) would disprove John’s point about the decline of Christianity among the younger generation.

The Beatles were filmed between shows by a British news team preparing the thirty-minute documentary The Beatles Across America for the ITN program Reporting 66. Host Richard Lindley had interviewed Tommy Charles in Birmingham and Imperial Wizard Robert Shelton of the KKK faction the United Klans of America in Tuscaloosa, had filmed a record burning in Georgia, and was going to the youth revival meeting booked to clash with that night’s concert.

Q: What difference has all this row made to this tour, do you think? Any at all?

PAUL: Umm, I don’t think it’s made much. It’s made it more hectic. It’s made all the press conferences mean a bit more. People said to us last time we came, all our answers were a bit flippant, and they said, “Why isn’t it this time?” And the thing is the questions are a bit more serious this time. It hasn’t affected any of the bookings. The people coming to the concerts have been the same, except for the first show in Memphis, which was a bit down, you know. But, uhh, so what?

Q: The disc jockey, Tommy Charles, who started this row off, has said that he won’t play your records until you’ve grown up a little. How do you feel about that?

JOHN: Well, I don’t mind if he never plays them again, you know.

PAUL: See, this is the thing. Everyone seems to think that when they hear us say things like this that we’re childish. You can’t say things like that unless you’re a silly little child.

GEORGE: And if he [Charles] was grown up, he wouldn’t have done the thing ’cuz he only did it for a stunt, anyway. So I mean, who is he to say about growing up? Who is he?

JOHN: [demandingly] Who!!

PAUL: [jokingly to George] Who is this guy?

JOHN: [smiling] Other than that, it’s great.

PAUL: Quite a swinging tour.

Q: Do you feel that Americans are out to get you . . . that this is all developing into something of a witch hunt?

PAUL: No. We thought it might be that kind of thing. I think a lot of people in England did, because there’s this thing about, you know, when America gets violent and gets very hung-up on a thing, it tends to have this sort of “Ku Klux Klan” thing around it.

Q: It seems to me that you’ve always been successful because you’ve been outspoken, direct, and forthright, and all this sort of thing. Does it seem a bit hard to you that people are now knocking you for this very thing?

JOHN AND PAUL: [smiling and nodding with comic exaggeration] Yes!!

JOHN: It seems VERY hard.

They dealt with the tension in the air by joking with each other as they prepared for the day’s final show. “Send John out. He’s the one they want,” said George. “Maybe we should just wear targets on our chests,” Paul suggested.

The audience was enthusiastic and screamed throughout. Three songs into their set, as the group was performing George’s “If I Needed Someone,” a firecracker hurled on stage from the balcony made a sizeable explosion at the foot of Ringo’s drum kit. For a few seconds, on the final verse of the song, the screams turned into a collective gasp of shock. The Beatles themselves quickly looked around at each other to see which one of them had been shot but resolutely played on to the end. A young man (some newspaper reports said three young men) was seized by police and ushered out of a side exit. “They didn’t miss a note,” one pleasantly surprised audience member told the New York Times.

The August 20 show in Cincinnati had to be postponed because of torrential rain and was rescheduled for the next day. The Beatles were already playing an evening show in Saint Louis, Missouri, so they had to do Cincinnati at noon, then travel to Saint Louis for the evening concert. It was while standing out on the covered stage in Saint Louis as a storm broke over them that Paul finally decided that, like George and John, he no longer wanted to tour in this way. After the concert they flew to New York and checked into the Warwick Hotel at Fifty-Fourth Street and Sixth Avenue, ready for their return to Shea Stadium in Queens on August 23.

On August 22 they gave two press conferences at the Warwick. The first was for journalists and followed the by-now-predictable pattern. There was only one question about the Jesus comment (which John batted away by saying he’d already dealt with it), but there were several that circled around the suggestion that the Beatles’ days as a performing group might be nearing their end. Was the low turnout of fans at the airport when they flew in an indication of declining popularity? (No.) Would John and Paul consider retiring from the stage and becoming the new Rodgers and Hammerstein? (No.) Had they ever considered individual recording careers? (No.)

On August 3, during the early days of the controversy, NEMS had announced that John was to star in a film to be directed by Richard Lester (director of A Hard Day’s Night and Help!) called How I Won the War. This fueled rumors that each Beatle was going his own separate way, but John took great pains to explain that he’d only taken on the role at Lester’s invitation—he wasn’t seeking a film career—and filming would take place during a period when the Beatles weren’t scheduled to be working.

Someone asked if they were doing “a Bob Dylan in reverse.” He had started by doing folk songs and had moved toward rock ’n’ roll. They had started by doing rock ’n’ roll and had moved toward folk-rock. “That thing about Bob Dylan is probably right,” Paul agreed, “because we’re now getting more interested in the content of the songs whereas Bob Dylan is getting more interested in rock ’n’ roll. It’s just that we’re both going towards the same thing. I think.”

The other press conference was for a selection of young fans and was a Beatles initiative. Both the New York Top 40 radio station WMCA and the Official Beatles Fan Club of America asked fans to send in postcards with their details, and seventy-five fans from each group would be picked to attend the Junior Press Conference. The belief was that the questions of teenagers passionate about the music of the Beatles might be more refreshing than those of jaded journalists, many of whom didn’t necessarily like the group or know much about their music. WMCA alone received forty-eight thousand cards.

It was a more light-hearted affair than the grown-ups’ conference but yielded no big revelations. Many of the questions started “Is it true that . . . ?” and then cited a news report. Others were about the songs. Fans wanted to know whether they were about real events or real people. Apparently a story had circulated that there was an actual Eleanor Rigby who hung out with the Beatles.

During the day two teenage girls from Staten Island—Carol Hopkins and Susan Richmond—failing to gain entry to the Warwick, where the press conferences were taking place, had climbed out onto a narrow ledge on the twenty-second floor of the nearby Americana (where Epstein had made his initial defense of John’s statement earlier in the month) and threatened to throw themselves off the building unless they could meet John and Paul. The police set up barriers to clear the sidewalks and spent twenty minutes coaxing the girls back to safety.

The Shea Stadium concert became an anticlimax. Almost exactly a year before the Beatles had played the same venue to a sellout audience of 55,600. It was the biggest crowd they had ever played to and set a world record for attendance at a pop concert and also for box office takings. This time there were eleven thousand empty seats despite tickets having been on sale for over two months. This led to fresh media speculation that the Beatles had already reached their peak. (Timothy Leary’s eighteen-year-old daughter, Susie, was among those who attended.)

The latest Newsweek on the stands in Manhattan had a story titled “Blues for the Beatles” that focused on what it saw as the group’s inevitable decline. The low turnout at Shea “suggested that the Beatles’ era of sure-fire sell-outs had passed.” The group members were now “married, rich and rococo.” They were out of touch with their audience. “Their music, now baroque and folk, has cooled off many who used to pack the palladiums,” it announced.

Astonishingly, although the Beatles had conquered New York, they had never really seen it, because they were cosseted by security and restricted by schedules. Only George had ever hit the tourist trail, and that was because he’d made a solo visit in 1963 when the group was not known in America. Asked to compare New York to London, John was forced to admit, “I just don’t know. I haven’t really seen enough. I’d like to but, you know, unless they blow it up I’ll come and see it. It’ll still be here.”

After the concert they flew directly to Los Angeles, boarding the first-class section of their plane while it was in a hangar to avoid detection by the fans. While on the flight across America Art Unger from Datebook spent around five hours talking with George (“It’s unusable, of course,” Unger confided in notes he recorded immediately afterward; “it’s about life and LSD etc. etc.”), before briefly talking to Ringo, who was the first of the Beatles to openly admit the possibility of the four of them going their separate ways. The worst thing about this was that, he confessed, “I couldn’t stand never seeing the lads again.”

Acknowledging that each Beatle was looking for new projects to get involved in, he explained that he was still considering opening a hairdressing salon or a club. He was the most content but the least secure of the group. He was not a composer or a singer of note, and had no substantial publishing royalties to fall back on, having only had one partial writing credit thus far. “I’ve always been short and small and all the other guys seem to get along but I’m not sure that I can [make a solo career out of music] because all I do is sit there and play the drums. I don’t even like the way I sound when I sing. I’m not a millionaire. I am the poorest of the four. George and I are the poorest, although George has a bit more since he wrote a few songs.”

A fan’s-eye view of the Curson Terrace property rented by the Beatles in West Hollywood for their dates in Seattle, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

Arthur Unger Papers, State Historical Society of Missouri at Columbia

The Beatles liked Unger. Not only was he a vital connection between the group and its base audience of nine- to fifteen-year-olds, he also was a sophisticated and intelligent man whose interests ranged from Broadway musicals to the Mayan civilization. As a gay man in New York he was knowledgeable about some of the city’s fringe scenes, and they were interested in hearing his stories about theatre, art, and literature.

Timothy Leary had introduced Sanford Unger, Art’s brother, to LSD. He was now a prominent psychologist researching the potential benefits of treating neurosis sufferers with hallucinogenic drugs. One of his most cited academic papers was “Mescaline, LSD, Psilocybin and Personality Change,” published in the journal Psychiatry in May 1963. In 1965, he had been featured in a major CBS documentary, LSD: The Spring Grove Experiment.

Datebook, despite its young readership, had already tackled the topic of hallucinogens in a double-page spread, “LSD: Newest Teen Kick,” in which Art Unger had balanced differing views on the still-legal drug. “The librarian in your local library may be able to help you track down exciting reading matter on the subject. Read up on LSD now—you can still be in the forefront of those with any real knowledge about what may be a revolutionary development in man’s ability to appreciate himself.”

Unger had yet to experience the drug, but his brother had offered to administer it to him under clinical conditions and guide him through the trip. Paul, in particular, thought this was a good and sensible offer and encouraged him to accept. He would do so in October and write to Paul with a detailed description of a trip that he considered “an ecstatic experience filled with wild, soaring, multiple perspectives.”

Although the flight arrived in LA in the early hours of the morning, there were around four hundred fans awaiting them. The Beatles were driven to a gated compound with an eighteen-room house at 7655 Curson Terrace in West Hollywood that Brian Epstein had rented for the rest of their tour. Before leaving England George had told a journalist, “I’m not looking forward to [the tour] much, except for California, which comes at the end. There at least we can swim and get a bite to eat.”

On August 24, their supposed day off, the Beatles relaxed around the pool with Joan Baez, David Crosby, Art Unger, Atlanta DJ Paul Drew of WQXI, and Ray Morgan of KLIV in San Francisco; they played billiards in the game room, swam, and played with a large plastic yellow submarine given to them by a fan. Late in the afternoon they were driven to the landmark Capitol Records Building at Hollywood and Vine, where, at six o’clock, they gave a press conference and also met with Robert Vaughn from the popular TV espionage series The Man from U.N.C.L.E.

The press conference revealed little that wasn’t already known. This wasn’t entirely the fault of the journalists. The Beatles had perfected the art of nonchalance in the face of inquisition. What was their most memorable occasion? “No idea.” How does filming compare with recording? “We don’t compare it much, you know.” Would they prefer to play the Hollywood Bowl rather than Dodger Stadium? “We don’t mind.” What was the meaning of the butcher album cover? “We never really asked.” How much had they made on the tour? “We don’t know about that.” Would they be touring America again in 1967? “Ask Brian.”

The one potentially interesting line of investigation wasn’t pursued. A journalist asked whether they would ever consider recording in America. The question appeared to take them by surprise, but once Paul had started talking he had to carry on:

PAUL: We tried actually, but it was a financial matter. Mmm, mmm! A bit of trouble over that one. No, we tried but—it didn’t come off.

GEORGE: Internal politics.

PAUL: Hush hush.

RINGO: No dice.

JOHN: No comment.

No one followed up to find out when, where, and with whom this happened. Paul’s “Hush hush” and John’s “No comment” suggest either that the subject was off-limits or that if they told the truth, it would stir controversy. The conference ended with the Beatles being awarded a set of branding irons by Debbie Pinter, Yolanda Hernandez, and Stephanie Pinter of the Dallas Beatles Fan Club Charter. Two years before in Dallas the girls had given them ten-gallon hats they then wore on a photo shoot at a local farm.

When the conference was over, they hung out with David Crosby and Mama Cass and the next day flew to Seattle for two concerts. A rumor had swept Seattle that Jane Asher was flying in and that Paul was going to marry her there and then. At an afternoon press conference at the Edgewater Inn Paul was asked to confirm this story:

PAUL: It’s tonight, yeah.

Q: What time and where?

PAUL: Tonight—I can’t tell you that, now can I? It’s a secret.

GEORGE: We don’t want all the people there, do we?

Q: You are confirming the report?

PAUL: No, not really. It was . . . it’s a joke. Who started this? Anyone know? Does anyone know? I just got in today and found out I was getting married tonight. No, she is not coming in tonight as far as I know.

GEORGE: And if she does, we are going out tonight anyway . . . so we’ll miss her.

Jane was actually in Scotland. At a lunch in Edinburgh with the omnipresent Don Short, she laughed off the rumors of an imminent marriage to Paul. “We’re perfectly happy as we are,” she told him. “We may not marry for some time, quite possibly for years. I just can’t say.”

Speaking to Unger for Datebook, Paul was equally noncommittal. Asked how he felt about Jane’s plan to tour America with the Old Vic next year, he said. “I won’t try and stop her. It’s a drag. I’d rather she didn’t or I’d rather we were together for the four months.” What does a boy of twenty-four do when his girl goes away? Does he wait, or date? “He has no idea what he does” was Paul’s answer. “It hasn’t happened to him yet. He hasn’t got a clue. Anything could happen. It depends, you know, as everything depends. It’s all relative.”

In the past, male pop stars had risked destroying their appeal to a female audience by going steady or marrying. Even John had initially concealed his marriage to Cynthia. “Some pop musicians don’t even associate with women because they believe they’re not allowed to once they’ve become stars,” Paul admitted. “They believe that they’re wrecking their lives for their sake of their careers. That kind of thing is no longer important to me. You reach a point where you realize that the most important thing is to sort your own life out, and then possibly start indulging yourself and catering for other people.”

It was also still risqué for stars to give the impression that they were sexually involved with partners they weren’t married to. The year before Ringo had been asked in an interview, “Do you think a pop star could live in sin today without damaging his career?” and he had answered, “I don’t really know. But I’m sure the mums and dads would hate him because they are trying to bring their kids up right.” When Paul was living with the Ashers, he always made it clear that he had his own room and even when he moved to Cavendish Avenue spoke of Jane as a girlfriend who visited rather than a cohabitant. When Hunter Davies interviewed Paul at home in 1966, he reported in the Sunday Times that he “lives alone.”

It was harder to pretend that they slept separately when they vacationed together. “Going on holiday with Jane? That doesn’t bother me at all, because I know in my mind that there is nothing wrong with it. To people who want to ‘keep television clean’ and don’t like miniskirts it would be scandalous. They’d love to think we were chaperoned everywhere but I’m afraid that doesn’t fit in with what I believe. It would be hypocritical of me to pander to their tastes rather than my own.”

AFTER THE SECOND CONCERT IN SEATTLE THE BEATLES FLEW back down to Los Angeles to stay at their Hollywood home. The next two days were for rest and relaxation. On one of them Derek Taylor invited Paul and George over to his home in Nichols Canyon to meet Brian Wilson and his brother Carl. On being introduced Paul broke the ice by saying “Well, you’re Brian Wilson and I’m Paul McCartney so let’s get that out of the way and have a good time.”

The lights were turned down low, the Glenn Miller Orchestra played on the turntable, and the four musicians talked together for two hours. During the evening David Crosby joined them and Brian Wilson previewed a new Beach Boys track that he’d been working on for eight months. It was the most complex and labor-intensive single ever recorded. Wilson had used four studios, and his master version of the song, “Good Vibrations,” was compiled from the most outstanding sections of over ninety hours of tape. The recording of this one song had already cost more than the whole of the Pet Sounds LP.

Wilson’s meticulous method of assembling sounds and his decision to compose, arrange, and record rather than play on stage accorded with the growing feelings of the Beatles about their own future. The concert at Dodger Stadium in LA on August 28 illustrated the problems they now faced when giving a performance. The private security team hired to protect the group, US Guards Co., was stretched to the limit in shielding them from ravenous fans. Around seven thousand of the forty-five thousand in attendance broke through the fencing designed to separate them from the stage and tried to storm it once the show was over. The Beatles had to be taken to a safe room in the stadium until the crowd was under control and then were rushed away in an armored car. Over a hundred fans who had found where the Beatles were staying traveled to the compound, where police had to disperse them.

It was clear to everyone concerned that the Beatles couldn’t continue to perform in such circumstances. It was not only physically dangerous but also artistically unfulfilling. They were no longer the group that teenage girls imagined they were when screaming and professing undying devotion. Ivor Davis, New York bureau chief for London’s Daily Express, had been on the whole tour and on August 27 published a story titled “Could This Be the End of the Beatles Saga?” He quoted George saying, “Some nights I’m standing in front of the mike opening my mouth and I’m not even sure myself if anything is coming out.” Paul told him, “When we started at the Cavern people listened and we were able to develop, to grow, to create. But when the screaming started the first casualty was the humour we put into our performances. Now of course we are prisoners, with 50 per cent of our act taken over by the audience.”

It wasn’t only the Beatles who felt the pressure. As much as he delighted in the touring side of the Beatles’ career, Brian Epstein was finding it hard to maintain control as everything grew bigger and fraught with unprecedented problems. He sought relief in drugs and transient relationships with (usually) highly unsuitable young men who often took advantage of him both physically and financially.

While in Los Angeles he was paid a visit by “Diz” Gillespie, an aspiring actor from Ohio whom he’d hooked up with during the 1964 tour of America and subsequently brought to England to manage. There had been a dramatic falling out in London in 1965 involving threats, blackmail, and violence. Gillespie was now back, saying that he’d changed, and the gullible Epstein believed him, inviting him to share a meal with Epstein and Nat Weiss at the Beverly Hills Hotel. After Gillespie left the table at the end of the meal, Epstein realized that both his and Weiss’s attaché cases were missing from their rooms.

Epstein panicked. Among his papers were contracts, letters, barbiturate tablets, intimate Polaroids, and twenty thousand dollars in cash. There was enough to destroy him if it was either found by the police or turned over to a newspaper. Gillespie knew the precise fears that would be running through Epstein’s mind. He made an approach to Weiss demanding payment in exchange for the cases. Aware that he couldn’t involve the LAPD, Weiss hired a private detective, who was able to entrap Gillespie’s runner at the agreed drop-off point behind Union Station and have the case (minus the drugs, photos, letters, and eight thousand dollars of the cash) returned to its owner. Epstein was left humiliated. Weiss later spoke of it as the beginning of the serious depression that would create the circumstances leading to his early death.

The incident with the case was the reason why Epstein wasn’t around for the last concert on the tour in San Francisco, the city that, for those interested in the twists and turns of youth culture, was now competing with London as the hot place to be. The soon-to-be legendary Trips Festival, where LSD taking was blended with loud music and mesmerizing light shows, had taken place in January at the Longshoreman’s Hall near Fisherman’s Wharf. Bands that played at this event included Big Brother and the Holding Company and the Grateful Dead. The local scene was exploding with musicians exploring the potential of rock music that could change consciousness—bands with long and surreal names whose members had hair longer than the Beatles’.

New venues were catering to audiences that wanted to walk around or dance rather than sit and scream. The weekend before the Beatles arrived, promoter Bill Graham had presented the Thirteenth Floor Elevators, the Great Society, and Sopwith Camel at the Fill-more Auditorium, and Chet Helms’ Family Dog Productions had featured the Charlatans and Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band at the Avalon Ballroom. These were the new sounds for the older, tripped-out kids.

The musical outlook of these groups corresponded with that of the Beatles, particularly as showcased on Revolver, but because the Beatles flew in and out and didn’t come into the heart of the city, they didn’t visit Haight-Ashbury, where they would have seen the psychedelic street art, head shops, and impromptu concerts at the Panhandle east of Golden Gate Park.

Some of these innovators would see the show, including Marty Balin of Jefferson Airplane and Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead. “[The Beatles] were important to everybody,” said the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia. “They were a little model. . . . It was like saying ‘You can be young, you can be far-out, and you can still make it.’” The poster for the show was the work of Wes Wilson, one of the Bay Area’s foremost designers of psychedelic posters for concerts at the Fillmore and Avalon (as well as an op-art poster for the Trips Festival), commissioned by Tom Donahue, a DJ at KYA, the station promoting the event. It featured a yin/yang circle enclosing the Stars and Stripes and Union Jack and a photo of the Beatles on a background of red and blue dots. “Our common English-language culture and basic humanistic zeitgeist was contained in this symbolic sharing,” Wilson told me. “The British and American flags were united.”

The concert on August 29, held at the Candlestick Park baseball stadium, has become legendary as the Beatles’ final concert performance, but no one, neither the group nor the audience, knew at the time that this was the case. The Beatles flew up from Los Angeles in the afternoon, and the show was not notable for any other reason. Around a quarter of the thirty-two thousand available seats remained unsold; the organizers, Tempo Productions Inc., lost money as they’d guaranteed the Beatles a fifty-thousand-dollar fee (and had to pay a standby orchestra because of local musician union rules); and a cold wind was blowing across San Francisco Bay. Unusually, Paul asked Tony Barrow to record the sound using a cassette recorder. The Beatles themselves had preserved no other concert on the tour in this way.

The last Beatles concert, Candlestick Park, San Francisco, August 29, 1966.

Getty Images

Backstage (in the visiting-team clubhouse converted into a dressing room) they were visited by Joan Baez and her sister Mimi Fariña (whose novelist/poet/songwriter/performer husband, Richard Fariña, had been killed in a motorcycle accident four months earlier) and spent time talking to Ralph Gleason, an influential cultural critic contributing to the San Francisco Chronicle who would go on to found Rolling Stone magazine in November 1967 with the much younger Jann Wenner. As they talked each Beatle did drawings on the paper tablecloths with colored Pentel crayons at the request of the catering company, who wanted to display them in their shop. John did a huge yellow sun, Paul a psychedelic flower, George a psychedelic face, and Ringo a tiny comical face. Two days later there was a break-in at the catering company, and the cloth was stolen.

The UPI report of the concert concentrated on how much the Beatles would earn per minute for a thirty-minute performance and the behavior of fans that were kept in check by two hundred private security guards. It made no mention of music. The story concluded, “After the performance, the Beatles jumped into a waiting armored car and were driven off the field before anyone could get near to them.”

Tony Barrow told me: “It was probably one of the most average and ordinary concerts the Beatles had ever given. It lasted thirty minutes and musically was far from being the best. It was the end of a very tiring tour.”

The last number they performed was “Long Tall Sally,” the Little Richard song from 1956 that had been in the Beatles’ repertoire since their formation. It always became a standout performance for Paul. After its final chords had died away John wished the crowd good night and added, “See you again next year.” They flew back to LA on a chartered American Airlines plane. Once on board and at cruising altitude George turned to Tony Barrow and announced, “That’s it. I’m not a Beatle anymore.” Later he expanded on what he had meant. “We knew—this is it. We’re not going to do this again. We’d done about 1,400 live shows and I certainly felt that was it.”

John was sitting at the back of the plane as Art Unger approached him with a copy of the controversial issue of Datebook to ask for his signature. “Is this for you, or for the magazine?” John asked. Unger said it was for his own scrapbook. John took a pen and wrote “To Art with love from John C. Lennon.” “The ‘C,’” he told him, “stands for Christ.”

He invited Unger to take the seat next to him while the in-flight meal was served. They talked about everything from LSD and music to archaeology and anthropology, and Unger was left with the impression that John was lost and without direction. He repeatedly said that he would like to pursue certain activities based on his personal interests but each time would conclude that because of his position it would be impossible. In his notes Unger observed, “He was very depressed about everything. He felt there was no point in doing anything since it wouldn’t last very long anyway.”

One comment John made was so poignant that Unger scribbled it down. “There is so much I would like to do, but there is no time,” he said. “In ten years, I’ll either be broke or crazy. Or the world will be blown up.”

Reviewing the show in the San Francisco Chronicle (August 31, 1966) Ralph Gleason concluded with this prescient comment, “Is it all worth it? As a spectacle it is not without sociological interest, of course. As a performance it is, like John Lennon says, a puppet show. It can hardly continue to be attractive to four such rational, intelligent and talented human beings.”