The masses approached. Wall Street businessmen, wary from past demonstrations, encased their windows behind heavy timbers to protect against the crush. Civic leaders pleaded for restraint. Police made scores of arrests. But for one night the streets belonged to the mob. December 31, 1913, most agreed, was the “wildest” New Year’s Eve the city had seen in more than a decade.

By ten P.M., the city air popped with frost. The downtown canyons glowed from the lantern atop the Singer Tower, down past twenty-seven illuminated stories of the Woolworth Building, to the Edison arc lamps on the avenues. Crowds decanted from the cross streets into Broadway—tenement dwellers and denizens of “East Umpety-Umpth streets,” gentlemen wearing spats and slender worsted jackets, women swathed in a “kaleidoscope of colored and tinted gowns and wraps.” In dark spots where no light spilled, men in long coats discreetly inquired if passersby needed “a nice watch and chain, cheap.” And one cherub—quickly escorted to Bellevue—managed to defy fashion, the cold, and moral decency when he appeared wearing “no raiment between a cigar he was puffing and his shoes.”

For abstainers, the Society for the Prevention of Useless Noises had organized an edifying program of choral music and prayer. Their “Safe and Sane” celebration drew thousands to a solemn service where any display of verve was quickly throttled by the police. Officers arrested more than a hundred peddlers of rattles, buzzers, and clappers, and even confiscated confetti and false whiskers. But these raids only inflated prices; horns sold for as much as half a dollar, and enough customers violated the blockade on these “instruments of torture” that large portions of the city were debauched by the “blare of raspy throated tin horns, a clattering staccato tumult of wooden rattles, jarring bells,” as well as numerous other sounds emitted without any discernable purpose.

New Year’s Eve in a New York café.

An hour before midnight, the theaters released thousands toward the restaurants. Celebrants with foresight had reserved their tables a month in advance; throngs overran Reisenweber’s and the Marlborough. The owner of Rector’s, on Forty-eighth Street, thought he could have filled all of Madison Square Garden with the customers he was forced to turn away. Patrons at Sans Souci and the Café des Beaux Arts received complimentary souvenirs, direct from France. But the food and favors held no interest, and even the champagne sweated alone, untouched. Hurriedly throwing down their coats, the guests rushed the dance floors to fox-trot and tango. Between numbers, they visited their tables for a sip of brut or a nibble of something, but they did so absentmindedly, and only for tradition’s sake. “It was dance-dance-dance, everywhere,” a World reporter wrote. “New York literally abandoned itself to the seductive sway and swing and slide of the new sort of dance.” Couples spun in the basement wine vaults of the Astor, and they pirouetted on the rooftop of the Belvedere. They would not be refused, and even the fusty Waldorf begrudgingly cleared a small area for those who absolutely had to waltz.

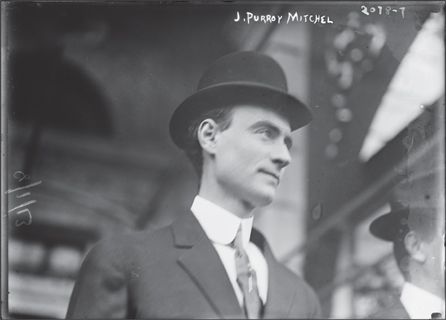

The toughest reservation in town was the Plaza. Two thousand luminaries filled the grillroom and packed the auxiliary salons and ballrooms, so that extra tables had to be placed in the corridors to accommodate the overflow. But hallway seating was not for the honored guests. Harry S. Black, the Realtor, Mrs. O.H.P. Belmont, a millionaire suffrage advocate, Elbert Gary of U.S. Steel, Stuyvesant Fish, the retired president of the Illinois Central—they supped comfortably in the main dining room. Nearby, at a table almost but not quite so well situated, sat a promising young couple: Mayor-elect John Purroy Mitchel and his wife, Olive.

Wiry and tall, at thirty-four Mitchel already looked like a man of authority. He had sharp, focused features and eyes “alive with the joy of fight.” This was his night, and these were his people. All round the room they scrutinized his precise, unaffected manners—a reporter for Hearst’s magazine thought he carried himself with an “almost patrician dignity”—and discussed his apparently limitless prospects. As course followed course, coworkers, elder statesmen, and chums from his Columbia days came to offer advice or congratulations. Among his own sort, Mitchel displayed “an infectious kind of gaiety, and an unusual capacity for friendship.” He greeted each well-wisher with the just-right tone, switching naturally from deference to bonhomie. “There was kind of an aspect of a young knight in shining armor about him,” a colleague recalled, “here was a man who wanted to run out the crookedness and inefficiency and do something brighter and cleaner than had been done for a long, long time.” He was master of himself, master of the room, and he would awake the next morning to become master of the greatest city on earth.

Mayor-elect John Purroy Mitchel.

No man, whatever his outward composition, could anticipate the prospect without a tremor. And Mitchel, in fact, awaited it with extreme apprehension. The perfect ease he felt with his peers was mirrored by the pure revulsion he experienced among the masses—the very multitudes who were now reveling on the Fifth Avenue sidewalks—who would imminently become the main of his constituency. With them he felt acute and obvious distress; the tension and toll of contact could knock him low with devastating migraines. Tomorrow he faced inauguration. No vision could be more terrifying—the previous mayor had shaken a thousand hands at his swearing-in. But that was tomorrow. As another acquaintance came to pay respects—or as the Neapolitan singers wandered into the main dining room—Mitchel set aside his shadowed cares. His pearl-and-platinum pocket watch displayed the hour; midnight approached.

ON THE STREETS, celebrations everywhere. Directed by hundreds of policemen, the crowds marched north along one side of the thoroughfares, south down the other. A horn-blowing but genial traffic jam extended, according to the Sun, “from Bowling Green up Broadway to Park Row, up Park Row to the Bowery, up the Bowery to Third avenue, up Third avenue to Fourteenth street, and so across Fourteenth street back to Broadway and up that thoroughfare of fun to some place probably near the north pole.” Rioting taxicabs and private autos posed an incessant menace. Impromptu parties enlivened the upper levels of the buses as riders traversed the routes back and forth just to view the scenes. Even the unfashionable districts above Central Park South participated. Young couples without the “necessary wherewithal” to afford the exorbitantly priced horns or prix fixe meals promenaded along the boulevards uptown—“125th street, ordinarily a live enough thoroughfare, was in a blaze of glory.”

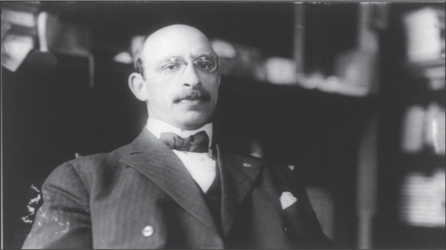

THE NATION’S MOST notorious anarchists were throwing a party in their Harlem brownstone. Notifications had gone out the previous week, inviting friends and comrades to “be among us to kick out the old year and meet the new.” By ten P.M., welcoming lights glimmered inside the three-story building at 74 West 119th Street that served Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman as home, office, and meetinghouse. They had moved there in September and already the location was well-known to the city’s radicals—as well as its detectives. But this was the official housewarming celebration. The evening “brought the procession of friends,” Goldman recalled, “among them poets, writers, rebels, and Bohemians of various attitude, behaviour, and habit.” They climbed the stairs to the main floor and were welcomed into a warm and chaotic sanctum that could easily accommodate a hundred guests. The young people waltzed to the gramophone. German Bundists poured stout brown beer. Italian sindicalisti swallowed Chianti. They reminisced; they gossiped. “They argued about philosophy, social theories, art, and sex.”

As midnight neared, “everybody danced and grew gay.” Typically, the hosts would have been the cheeriest participants. Goldman was known as a “great dancer.” Berkman was ever the gallant suitor, typically partnering up with one or two young ladies, and sometimes with “scores of other radical women.” But not this evening. Suffering through a spiteful separation with a younger man, Goldman felt “lonely and unutterably sad.” For Berkman, it had been years since he had surrendered himself to happiness. The arrival of each new year only reminded him of the fourteen that he had lost in prison. One time, in the Western Penitentiary of Pennsylvania, the inmates had stayed up past curfew. They had waited for the sounds from beyond the walls—ship sirens in the Ohio River, church bells, factory whistles—to inform them when midnight had come. The prisoners answered with what they had, and Berkman could hear it still. “Tin cans rattle against iron bars, doors shake in fury, beds and chairs squeak and screech, pans slam on the floor. Unearthly yelling, shouting, and whistling rend the air.”

Alexander Berkman.

In those years, he had grasped for the mercy of such vivid moments. Now, though he was a free man again, the immediacy of those thrills eluded him. The fanatical revolutionist of his youth had been replaced by this forty-three-year-old gadfly—bald, nearsighted, paunchy. For Berkman, another year meant another year older.

* * *

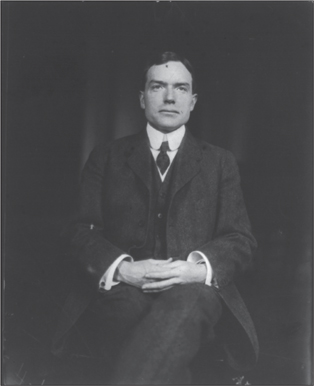

FROM THE 125TH Street station, it was only two stops on the New York Central Railroad to the village of Tarrytown, forty-five minutes—or “a rubber of whist”—away. A short automobile ride up North Main Street led to arcadian countryside, winding roads, the reservoir, and the well-watched gates of the Rockefeller family estate. Within this private preserve, John D. Rockefeller, Jr.—the thirty-nine-year-old son of the world’s richest man—passed the evening with his wife and children.

Their perfect holiday season had begun with stockings before breakfast on Christmas morning, followed by a musicale and gifts beneath the tree. Gathering in the schoolroom of their mansion on West Fifty-fourth Street, they had unwrapped their presents—a new sweater from his wife, for their daughter a bicycle. It was “a noisy, happy time,” with paper heaped round them, that lasted until the moment came to assail the turkey. After luncheon, they had crowded the automobile for a ride up to Fort Washington Park, scrambling down around the river just as a light snow began to fall. The next afternoon, the family journeyed to the Tarrytown property for a charmed interlude of “quiet and freedom.” They gave concerts for each other on the pipe organ, experimented with the new bike, went ice-skating, and took pony rides. “The children were as happy as their parents,” Junior wrote. Everyone was relieved to escape “from the rush and hurry of the city.”

Such casual ease was in itself an accomplishment for Junior, who had been drilled in austerity and self-denial. Wealth notwithstanding, the holidays had never brought indulgence. As a child, he once confided a Christmas wish to his mother. “I am so glad my son has told me what he wants,” she had then reported to a friend, “so now it can be denied him.” As he grew up, the family had kept to little gifts. This year, Senior had sent $1,000; Junior reciprocated with “a dozen white handkerchiefs, a dozen colored handkerchiefs and ten cravats.” But when it came to pleasing his mother, the game broke down. “I wanted so much to send you something particularly nice,” he apologized, “but have not yet seen just what I thought you would like; so to my chagrin and regret, I am sending you nothing. You know how queer I am about presents.”

Junior knew that few would sympathize with the burden of his wealth, but that did not mean it did not weigh upon him. “You can never forget that you are a prince, the Son of the King of Kings,” his mother had told him once, “you can never do what will dishonor your father or be disloyal to the King.” He sometimes felt he was not strong enough to bear the pressure. Shy and directed inward, he had “always had a very poor opinion” of his own abilities. Coming to work for Standard Oil after college, he had felt inferior even to the secretaries. “They can prove to themselves their commercial worth,” he explained. “I envy anybody who can do that.”

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., the son of the world’s richest man.

His desperation to show himself worthy led to neurasthenia, breakdowns, and depression. His lone ambition was to earn the name that he had never asked for, to redeem it to a nation that had come to associate “Rockefeller” with the cold villainy of the plutocratic class. To that end, he had quit the business life—retiring from the directorial boards of every company except for one—and dedicated himself to philanthropy. Through gifts and contributions, he was gradually crafting a new family legacy. As he approached middle age, Junior finally felt that he was becoming a substantial man, and no longer merely a man of substance.

A few nagging worries still tugged. There was his mother’s illness, which had kept her and Senior in Cleveland for the holidays. Renovations disturbed both his city and country houses. In politics, he had contributed thousands to Mitchel’s election fund, only to watch the new administration lure away several of his most valued advisers with the promise of important cabinet positions. And there was a coal miners’ strike in southern Colorado, affecting one of the few family concerns in which he was personally involved. Taken together, it was “a busy life” he was leading. But still and all he was confident and secure—at least by his own standards—and capable of heeding the counsel of his minister that “cares should sit lightly upon us at this Christmas season.”

By removing himself to the countryside, Junior had also removed another potential irritant. The New Year’s Eve celebrations in the city, coursing up and down the avenues near his home, grated on his sensibilities. He had never tasted alcohol, puffed a cigar, or played a hand at cards. It wasn’t until his freshman year at Brown University that he had first attended the theater or participated in a dance. The tango continued to be a mystery to him. He found the hotel parties, the mobs in the streets so distasteful that each year he contributed one hundred dollars to the Safe and Sane New Year’s Committee, which hoped to “do away with the noisy rowdyism which heretofore has marked New Year’s Eve in this city.” But until that was accomplished, Junior would flip the calendar in the inviolable security of Tarrytown.

PRESIDENT WOODROW WILSON observed the new year in the Gulf Coast town of Pass Christian, Mississippi, far from the crush of the capital. His first nine months in office were being acclaimed as an unprecedented triumph. He had lowered the tariff and introduced a national income tax. Two days before Christmas, he signed the Federal Reserve Act, sealing his greatest victory of the year. But the effort of it all had smashed his health; he suffered from fevers and indigestion. “I have been under a terrible strain, if the truth must be told,” he confided to a correspondent. “I realize when I stop to think about it all that I never before knew such a strain as I have undergone ever since Congress convened in April.”

On the morning of December 24, he and his family staggered to a private railroad car—accompanied only by the Secret Service, a physician, and a single stenographer—for a long journey south. This was to be a strict vacation. Official affairs would have to wait; there were to be “absolutely no social diversions or political callers.” Admirers crowded the tracks at every junction, but most left disappointed. The president slept much of the way, emerging at a few stops to shake hands, and then retiring to nap some more. “He is taking life just as easy as possible,” a newsman wrote.

For the next three weeks, a cottage overlooking the beach became the winter White House. To assure the president’s tranquility, villagers were barred by local edict from approaching closer than three hundred yards. Wilson played golf, walked the strand, and ignored the scores of letters and telegrams that arrived for him in every post. He marked his fifty-seventh birthday and began to display some of his former vigor. His grippe was gone, the physician said; the treatment was taking effect. “For the first time since he left Washington,” a reporter observed, “the President had a ruddy glow on his cheeks.” Renewed and refreshed, his attention once again returned to matters of office. He looked to his correspondence. A second stenographer was hired. He conducted secret discussions concerning the ongoing civil war in Mexico, the troubled neighbor that loomed beyond his sight across the waters of the Gulf.

On December 31, on a shopping trip in the village, he purchased a toothbrush and a lamp shade while the locals gawked at him through the store windows. New year’s congratulations began arriving; the first was a telegram from Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany. But the president himself did nothing special for the occasion. His regimen demanded nine hours of rest each day, and he was asleep long before the stroke of midnight.

Woodrow Wilson and his wife Ellen at Pass Christian, Mississippi.

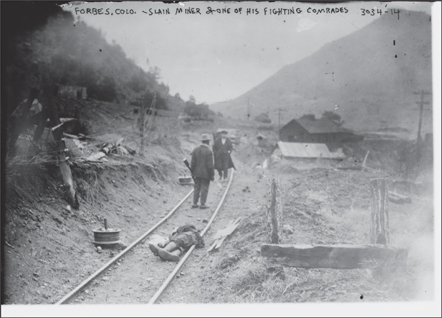

THE SNOWDRIFTS STOOD shoulder-high outside the Denver offices of the United Mine Workers of America. The greatest blizzard in the history of the state had passed through three weeks earlier, and the sidewalks were still treacherous with ice. At the country club and the county hospital, volunteers arranged the decorations for the night’s gala parties. Hostesses hurried home with their provisions, struggling to stay upright on the rimy sidewalks. Temperatures close to freezing had residents of the poorer districts anxiously appraising their stores of coal. Nationally, production had reached a record peak, but in Colorado, where fourteen thousand miners had been on strike since September, reserves had dwindled and prices were up. The mayor had been forced to institute emergency measures to keep the workers’ quarters supplied.

Two hundred miles south, at the colony of Ludlow, the storm had threatened to collapse the tents that served as temporary lodging for the striking miners. Ten-foot-high walls of snow flanked the paths that inhabitants had hacked throughout the camp. A large tree had been adorned with Christmas ornaments to give the bleak settlement some approximation of hominess, and supporters had shipped in thousands of baskets, filled with “candies, fruit, and sweets for the children.” December 25 had been too cold for a communal celebration, so families had shivered inside their separate tents while a union leader dressed as Santa Claus trudged from door to door, distributing the “goodies.”

It was gloomier still in the nearby town of Trinidad, where twelve hundred state militiamen made their barracks. “Lavish” decorations and holiday boxes from home brought scant cheer to men who had just learned of their general’s orders to close down all saloons in the area. For employees of the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, this disappointment had been exacerbated by the news that smoking was now to be forbidden on company property. “If John D. lives much longer,” complained an angry employee, “we will start each day with prayers and finish it with a service of song.”

For months, these rival encampments had existed in a state of tension, awaiting the catalyst that would instigate unbridled war. The soldiers were supposed to be maintaining peace between the workers and the mine owners, but their officers’ loyalty was to the bosses. Ten men had already been killed in the conflict. The jails in Trinidad were crammed with dozens of labor sympathizers, and the strikebreakers—many of whom had not known they were coming to scab—had to be kept under perpetual guard to prevent their escape.

In southern Colorado, a months-long conflict between striking miners and the state militia had already resulted in ten deaths.

In this gruff and vicious atmosphere, no excuse was needed to go and start a fight. On the morning of December 31—responding to news that the strikers were assembling a cache of weapons—forty soldiers marched from Trinidad to Ludlow. The officers negotiated with union leaders. Behind them, two units of cavalry and several infantry companies stood at the perimeter of the camp, a machine gun trained on the tents. Then the mining families stood by while the troops overturned mattresses and scattered furniture, ransacking their homes for armaments. After an hour’s search, which netted fifteen assorted handguns and rifles, the militiamen marched back across the blank tundra, their departure tracked by the eyes of hundreds of resentful strikers.

FROM HARLEM TO Wall Street in New York, Broadway “was a solid lane of noisy, convivial humanity.” Midnight approached, anticipated by “a welcoming crowd,” a Tribune reporter calculated, “whose numbers would baffle an army of census takers.” Millions “and then a few” packed the boulevards. At 11:55 P.M., the naval radio towers in Arlington, Virginia, began emitting electric signals—“corrected by stellar observation to the most exact time possible”—over a radius of twenty-five hundred miles. The beats reached ships in the North and South Atlantic; they were heard atop the Eiffel Tower and at the nearly completed Panama Canal. When the last pulse sounded: 1914.

In the streets, the din re-echoed for many minutes past the hour. For participants, wrote a columnist for the Evening Post, the experience approached ecstasy:

The whole city seems half delirious. Five minutes in the crowd and you are half delirious, too—you, a New Yorker, in staid, unfeeling, unemotional old New York—yelling your head off, slapping strangers on the back, talking and shouting at the top of your lungs, laughing endlessly, hysterically.

Gentle applause and tinkling crystal warmed the main dining room at the Plaza Hotel at midnight as the Realtors and railroad executives, the senators’ daughters and financiers’ widows, toasted success to John Purroy Mitchel and his administration. An hour later, the doors of the Grand Ballroom were thrown open, and a forty-piece string orchestra struck up the night’s first two-step. Couples paired around the stone floor—men in white waistcoats and bold-wing collars, women in beaded gowns and chiffon frocks. Taking positions along with the rest, the mayor-elect and his wife clasped each other’s hands, locked eyes, and began to move. Mitchel waltzed famously. “He is frankly and openly a devotee of the dance,” a reporter wrote. He “can tango a l’Argentino, and he is also perfect in the modified one-step and the standardized hesitation, to say nothing of the lame duck, the lively maxixe and the vivacious canter.”

Across the city, dancers with far less self-government spun and kept spinning. “Anybody with his ear to the ground,” a participant later recalled, “could have heard all over town the sprightly patter and tap of patent leather pumps.” Time grew ragged. Lips dried and cracked. Champagne flattened, spilled, and gummed the floors. As the sun rose, rumpled gentlemen and women “whose hair was beginning to sag from the lines of beauty” still lumbered on the mosaic tile in Delmonico’s. Across the street, at Sherry’s, the rugs were rolled up and tossed aside to make room for the tango. Couples were turkey trotting in the subway stations beneath Times Square.

Dawn approached and the accounting began. “Confetti, broken horns, wrecked rattles, fancy paper caps and other junk lay dismally along” Broadway. An estimated fifty thousand bottles of champagne had been consumed, as well as a “fortune in the more plebeian beer, highballs, and cocktails.” Rector’s alone had earned ten thousand dollars during the night.

As the sun rose over Brooklyn, the very last stragglers stumbled toward Jack’s, the all-night restaurant on Sixth Avenue, to honor one final tradition. Settling in at the oyster counter, they recorded their resolutions for the coming year.