“I wisht they’d hurry up.”

“Look at the cop watchin’.”

“Maybe it ain’t winter, nuther.”

—THEODORE DREISER, “THE MEN IN THE STORM”

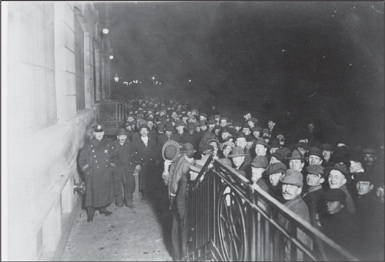

They arrived early at the Municipal Lodging House in January, gathering out front during the afternoon and waiting hours for admittance. By evening they stood ten wide, blotting out the sidewalk, stretching down East Twenty-fifth Street and around the corner to First Avenue. Their hats no longer kept to shape. Fists rooted deep inside coat pockets. On the coldest nights, as many as two thousand men, as well as dozens of women and a few children, queued outside—nearly twice as many as the facility could accommodate. Of all the homeless in New York, these were the neediest cases: They could not afford a dime for a bed at one of Manhattan’s hundreds of cheap hotels, they did not possess the pennies it took to sleep in the back room of a saloon. With no friends or relatives to shelter them, they had no choice but the last resort, to ask for the city’s charity.

“Ain’t they ever goin’ to open up?”

Toward the front: smiles and jostling. Fewer jokes further back. There was “no anger, no threatening words,” only “sullen endurance.” The newspapers called them loafers. College students went slumming to observe them. To sociologists they were “human derelicts and poor stranded flotsam and jetsam.” Among the hundreds and hundreds of homeless, perhaps a few deserved these derogations: the rounders, Bowery bums, and “confirmed beggars.” Others were broken and without hope, the “physically disabled, the mentally deficient, the infirm from age.” Many had succumbed to “intoxicating liquors.” But most were vigorous “native sons” of New York, “a collection of broad back, red faced, strong armed young men,” who had been victimized by a devastating industrial recession. Bakers, barbers, printers, teamsters: Their motive power had built the subways and office towers, unloaded ship cargo onto the piers, operated the machines of production. Chance had not befriended them, and it was their fell misfortune in this grave-cold winter to be “reserve labor out of place and out of season.”

A crowd of men outside the city’s Municipal Lodging House.

At six P.M., the doors opened and the line stuttered forward. There was “push and jam for a minute,” but the policemen at the entrance—as well as an attendant with a blackjack—demanded order, and the shoving steadied into a blank progress of “hats and shoulders, a cold, shrunken, disgruntled mass pouring in between bleak walls.” Outside, fear increased as the line shortened. At any moment, the gatekeepers would shout, “Beat it!” or “All out!” The door would slam closed, and the unfortunates still on the street would spend the night folded up between the iron armrests of a park bench.

Those who made it inside faced interrogation. “They are told that they must go back to their relatives, or made to feel at once that they can stay but a very short time, or spoken to as if they were not making an effort to get employment.” Anyone who possessed twenty-five cents or more was told to leave: The city’s largesse was only for the utterly destitute. Once past the questioners, inmates were taken to the basement and forced to strip and shower. In another room, their pockets were rifled by the orderlies—the unwritten law of the lodging house was “findings is keepings”—and then their clothes were fumigated. Dinner was plain and meager, though a few coins could supplement the fare with a smuggled chop or some eggs.

Not so many years had passed since the city had sheltered its homeless in a boat moored to an East River dock. After that, the derelict were quartered in the city morgue. But those days were gone; the Municipal Lodging House on East Twenty-fifth Street had opened in 1909 at a cost of half a million dollars, and it was “one of the most elaborate of its kind ever erected” with public funds. Containing 750 beds, it was the Department of Charities’ most important resource. Visitors on guided tours agreed that it was an “exceptionally fine building,” as clean as a hospital. “The food being prepared looked wholesome.” The bedsteads were painted white; the sheets, pillowcases, and wool blankets were “freshly creased.” It was, a reporter decreed, “paradise for the wanderer.” It hadn’t taken long, however, for its shortcomings to reveal themselves. In the dormitories there was “rough talk,” beatings, bullying, thefts. The bunk beds, rowed from window to wall, were springboards for “tuberculosis, pediculosis, and other communicable diseases.” Though the building was just a few years old, it had been constructed without fire escapes.

At five A.M., the boarders were roused up and ushered out to litter the parks and streets. The next evening there would be more of them. The following week more still, too many to ignore. The number of homeless whom the city shelters could not accommodate had grown over the previous three years. In January 1912, the total had been 8,986. In 1913, it was 14,315. For 1914, the figure was predicted to double—to nearly 30,000. Though Mayor Mitchel acknowledged “an unusual condition of general unemployment,” which needed to be investigated, quantified, and eased through efficiencies, he saw no cause to entertain “various suggestions of an extreme nature.” Childishness, snorted Berkman: The profit system would always demand desperate, available laborers. “Modern civilization spells the paradox: The more you produce, the less you have; the more riches you create, the poorer you are.”

* * *

JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR., had been feeling rather homeless himself lately. Workmen had only just vacated his new mansion on Fifty-fourth Street, and though the family had occupied it since September, several rooms remained undecorated. Up north, his lodge on the Tarrytown grounds was undergoing renovations too, and the racket of building emanated from construction sites at the stables and the front gate. Furniture was continually being crated and uncrated, shipped, lost, dropped, chipped, shattered. With all these distractions—the maid had “been rushed from morning till night!”—everyone was exhausted. For a full week after the new year, Junior and his wife, Abby, did not rise for breakfast once. “We slept,” he wrote his mother, “as we had not slept for weeks.”

But then the vacation was over and they reluctantly returned to Manhattan. The older children—Babbie, John, Laurence, and Nelson—resumed classes and music lessons. Rockefeller went back to his suite of offices on the top floor of the Standard Oil Building at 26 Broadway, where a pile of correspondence awaited his attention.

He had hated working here at first, and had merely come to tolerate it since. For years he had attempted to impersonate a business executive, but the effort had resulted in little more than a succession of nervous collapses. The more he understood the realities of industry, the less capable he was of participating in them. He was an idealist. He was sensitive. Swindled by a stock scam, witnessing his colleagues giving bribes to party bosses at the back door—these experiences led to a crisis of conscience. Even the office furnishings—massive rolltop desks, bare walls, mustard-colored carpets, overstuffed chairs in need of “the attention of an upholsterer”—were abhorrent to his delicate tastes.

After a decade or so, he came to the same conclusion as the muckrakers: Modern corporations were so large that they could not be held to high ethical standards. He sat on the boards of directors for about a dozen companies. Somewhere within these firms, people were offering political kickbacks, manipulating stock, exploiting workers. Whatever misdemeanors they committed, they did so in his name. If there was a scandal, publicity would inevitably focus on the Rockefellers, and it would be the Tarbell series all over again. The thought tormented him. Finally he decided he had “to live with his own conscience,” and so, in 1910, at the age of thirty-six, he had announced his retirement from business.

In the four years since, he had continued working in the office, but his focus had shifted to philanthropy and social reform. Serving on a grand jury to investigate the “social evil”—as prostitution was euphemistically called—he had discovered a side of the city never glimpsed during his cloistered Baptist upbringing. At the end of a rigorous inquiry, he presented his findings to the public. There was brief interest, and then nothing. The revelations were sensational, but Tammany, which was complicit in the corruption, had little will to pursue them. Junior did not give up. Realizing a sense of his own mission, he decided to use his family wealth for social causes; the Rockefeller fortune could bridge the gap between “seeing the need for and getting done.” He founded the Municipal Research Bureau, which launched studies on prostitution and policing practices. His Bureau of Social Hygiene opened a laboratory to examine the sexual habits of women inmates at the Bedford Hills reformatory.

This was vital labor, and by 1914 Rockefeller was a recognized patron of reform, “a much more important man to the country and to the world,” decreed Current Literature, “than he ever would have become as a financial magnate.” But accolades just masked the fact that the actual work was being done by others, while Junior’s time still went to accounting for expenses, signing receipts, and other drudgery. “No one else can do the big things as well as you can,” his wife consoled him, “no one has the faith, the courage and the persistent desire that you have.” But, she continued, “I have felt with deep regret, that others were doing the inspiring part of your work while you poor dear were looking after the details of the neglected work of some underling.” In her opinion, there was no need for her husband “to be quite so modest as he is.”

JUNIOR LOOKED TO the letters and memoranda that had crowded on his desk during his absence. It was the usual assortment of looming crises and petty annoyances: Christmas cards, entreaties, expense reports.

Several documents dealt with the incoming administration. Junior admired the new mayor. He had been one of the largest contributors to the campaign and had written a warm letter of congratulations after the victory in November. With the anti-Tammany Fusion candidates elected, he hoped that all the private work he’d done would finally prove useful to the public authorities. “As you know,” he wrote Mitchel in December, “the Bureau of Social Hygiene, with which I am connected, has been at work for several years, studying in as thorough and scientific manner as possible the whole question of the social evil … It is the desire of the Bureau to render to you any assistance in its power in dealing with this subject.”

Before Christmas, he had gone to City Hall to meet with Mitchel, waiting for nearly an hour in an anteroom before being admitted for a few minutes of conversation. This was all that the mayor-elect could spare. He was living a nightmare of importunities and requests: Everyone in New York who had any connection to politics had a friend or relative to recommend for a position. But Rockefeller did not have to discuss appointees, since so many of his own people had already committed to joining the new government. Katharine Bement Davis, manager of his Laboratory of Social Hygiene, was the new commissioner of correction. The director of his Bureau of Municipal Research, Henry Bruère, was now city chamberlain. Raymond B. Fosdick, currently studying law enforcement in Europe, was a leading candidate to head the New York Police Department. If anything, Rockefeller worried that too many of his own people would be lured away.

Some on his staff believed that with a Progressive mayor in office, the Rockefeller bureaus had become redundant. A few even suggested that the continued existence of these private organizations would tempt Mitchel to inaction. “They believe,” internal memoranda suggested, “that a known large fund in the Bureau’s hands will paralyze the initiative of the administration.” But others—including Junior—thought that since they had already sacrificed Davis and Bruère, their duty now was to support them as fully as possible. A reform regime backed by Rockefeller resources could do unprecedented work for social uplift. “Our effort should be not merely to get an honest and economic administration,” Junior’s advisers concluded, “but to raise the standard so high as to make the Mitchel Mayoralty a memorable object lesson of Good Government and thereby a substantial asset of the reformer in future Municipal campaigns.”

Also on his desk was correspondence addressed to stockholders of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company. This certainly concerned him, since he and his father together owned 40 percent of the shares. In addition, Junior sat on the board; it was the sole directorship he had kept after his retirement from business in 1910. He had decided to stay on because the Colorado mining concern was one of the worst acquisitions the family had ever made. In the decade or so since the Rockefellers got involved, it had never made a profit, or paid a single dividend on its common stock. Junior had remained out of loyalty: He “had to see it through” until it had been put on a sound footing. He eagerly looked forward to the time when Colorado Fuel & Iron would be securely solvent and he could finally relinquish his last ties to the world of business. But that was looking like an increasingly distant prospect.

The family’s representative on the scene was Lamont Montgomery Bowers, a veteran executive with impressive successes in his past. But Bowers was a truculent opponent of organized labor, and in September—when miners across the southern Colorado coal fields had gone on strike—he had chosen to take an inflexible line. His was a dominating personality, typical of an earlier generation of business autocrats. Believing that his company treated its employees as generously as could be asked, he was convinced that agitators from the United Mine Workers were fomenting discontent among his uneducated, immigrant workforce. Bowers’s “whole attitude was paternalistic in character,” Junior recalled. “He had the kindness-of-heart theory, i.e., that he was glad to treat the men well, not that they had any necessary claim to it, but because it was the proper attitude of a Christian gentleman.” He hired replacement workers and private detectives and steeled himself for combat. Bowers would stand against the strikers, and from New York Rockefeller would stand by him, even if at times he felt that his older subordinate sometimes treated him like another one of his misguided employees. “You are fighting a good fight,” Junior wrote in early December, “which is not only in the interest of your own company but of the … business interests of the entire country and of the laboring classes quite as much.”

The newspapers were reporting that Mother Jones was back in Trinidad, Colorado, the town nearest to the center of the coalfields struggle. A matronly rabble-rouser, Jones went where the trouble was, traveling from strike to strike, encouraging the workers to rise up against their employers. Bowers had complained to Junior about her back in September, and the governor of Colorado blamed the entire conflict on her “incendiary teachings.” This time her visit was brief. Militiamen seized her before she had even stepped off the train, held her for two hours in the local jail, and then deported her to Denver. As the locomotive stirred, she had called out to the miners, promising to return to Colorado “as soon as it becomes a part of the United States.”

On the day after Christmas, Rockefeller had sent another letter before leaving for Tarrytown. And there were two new replies waiting for him when he returned to his office. The reports were mixed. “There are several hundred sluggers camped within the strike zone, who have rifles and ammunition in large quantities,” Bowers wrote, “we are facing a guerrilla warfare that is likely to continue for months to come.” On the business side, however, news was better. “Everything is running along about as usual,” the second note said. Men were deserting from the strikers’ camps. Nonunion workers were proving satisfactory. The mines were producing as much coal as the market demanded.

With the Colorado matters tended to, there was finally the business of the antiques for his new house on West Fifty-fourth Street. During the previous month, his home had been transformed into a gallery, with dozens of antiques on loan from dealers’ collections. Vases and sculptures, beakers and benches—he had arranged and rearranged them. And, unfortunately, he had broken some, too: A teakwood stand had splintered, and a Persian vase had crashed from the mantel in the dining room. Now, after weeks in the presence of these treasures, he was ready to commit to the items that had truly moved him. He struck a bargain, agreeing to pay for the damages in exchange for getting 10 percent off the entire transaction. He commissioned the dealer’s secretary to go from room to room, properly bracing and riveting the various stands and cabinets in order to prevent further destruction.

Junior had initially felt a little selfish collecting art objects, worried that he was buying for himself “instead of giving to public need.” But over time he had embraced the pleasure that material beauty inspired in him. After all, “he wasn’t taking bread from anybody’s mouth,” and the pieces would end up in museums anyway, so surely he was justified in spending some small part of his fortune on things that gave him joy. Wandering the rooms of his new mansion, carefully avoiding any more accidents, he savored the sense of occupying a space that he himself had designed to his own sensibilities. The money to build it may have come from his position in life, but nobody could accuse him of inheriting his taste. It was one of the few things he could truly call his own.

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller.

AN INFINITESIMAL MOVEMENT disrupted the predawn stillness. On the roof of the Whitehall Building, 454 feet above Battery Place at Manhattan’s southern terminus, the Weather Bureau’s thermograph machine took its reading. A trembling brass tube, filled with liquid, jarred a train of levers attached to a pen that bore down lightly, leaving a mark on a slowly rotating drum of graph paper: At seven A.M. on January 12, the temperature was 27 degrees.

Smoke puffed and clotted round the chimneys above a hundred thousand other rooftops. In the barren avenues, the streetlights had just switched off. A suggestion of sunrise showed from the east. Policemen relieved the peg posts, marking the shift change with a single tap of a baton to the sidewalk; in the silence, the thwack of wood on pavement could be heard for blocks. At 7:23 A.M., almanac dawn, the morning gun fired from the military installation on Governor’s Island; tugs and schooners in the harbor replied with whistles and jeers of their own. The elevated trains crowded up, rattling windows; subways droned below. From the South Ferry and Bowling Green stations, thousands of men, joined by high-heeled office girls displaying “their cold little legs in cheap bright stockings of imitation silk,” rushed toward the office towers. Hundreds made for the Whitehall Building and their desks at the White Star Line, the U.S. Realty and Improving Company, or O’Rourke Engineering.

Above their heads, the Weather Bureau accumulated data. The thermograph’s paper drum continued to spin; the line of ink grew jagged and started to descend. Beside it, the anemometer’s four gyrating cups creaked and then began to fly. An Arctic gale bore down, a wall of wind amplified and eddying among the tall buildings and narrow streets. The currents “seized old ladies and tangoed with them at crossings.” Women near City Hall had their legs knocked from under them; some were carried fifty feet or more until they were dashed into walls and autos. Falling signs and construction debris fractured skulls. A man was blown off an elevated station platform into the tracks; another was chucked into the East River. A schooner ran aground. Policemen abandoned their fixed posts, fleeing to the safety of the precinct houses. Smoke whipped from the chimneys and vanished in the onrushing currents. At three P.M., with the anemometer spinning nearly out of its socket, the forecaster’s register marked the wind’s velocity at seventy-four miles an hour.4

By sundown, Battery Park had emptied. Benches in the plazas and promenades sat vacant. “The Bowery was deserted,” a reporter for the Call described, “and the saloons, restaurants and similar places were filled to capacity with the shivering, emaciated mass of humanity, whose sole thought was to keep out of the cold.” Hundreds more went to missions, University Settlement, or the Salvation Army. And in numbers greater than on any other night in its history, they wandered toward the Municipal Lodging House. By eight P.M., the facility’s beds were filled. Latecomers received coffee in a tin cup and some hunks of bread. Some were taken to sleep in the city morgue. Others were led to the Charities Department docks, on East Twenty-sixth Street, where three ferry boats were moored. Once aboard they made do “on the benches, in reclining chairs, inside and outside the cabins.” They lay close together on the unheated ships, more than a thousand of them, newspapers and overcoats substituting for blankets.

Long after everyone else was settled, John Adams Kingsbury, the newly appointed commissioner of charities, remained active, stalking between the ferries, issuing directives, planning improvements. Until three A.M. he stayed among his charges, and by then he had seen too much to keep still. At thirty-seven years old, he was young even for Mitchel’s youthful administration. A leading theorist of philanthropy, he had not yet learned the policy of silence. “I consider that the present provision for this overflow is absolutely inhumane, inadequate, and indecent,” he stormed to reporters the next day. “The men are packed like sardines on the floors of the waiting rooms and docks and suffer severely from the cold.”

The new administration was stocked with nonconformists, but Kingsbury could be downright unconventional. “He is of medium height,” a reporter wrote, “well built, and wears a mustache and short beard, which cannot hide the kindliness of his face.” A former socialist, he had spent part of his childhood in an orphanage and took from that experience a deep sympathy for his work. Mitchel had no doubt that he was the “ideal selection” to head the Charities Department. “His good faith,” a colleague recalled, “was transparent.” If he lacked political experience, he profused good intentions. “Nobody could meet him without realizing he was an idealist, that he was disinterested, that he was an enthusiast in trying to accomplish what he thought to be good things.”

John Adams Kingsbury.

It wasn’t just the men sleeping in boats that riled Kingsbury. He had occupied his office for less than two weeks and already felt plagued with emergencies. Abuses tainted every division of his department. The Children’s Hospital was so polluted that patients arriving with a single illness promptly contracted several others.5 Students at the nursing school were dismissed for holding late-night ginger-ale parties. Insubordinate matrons grumbled at their superiors. The elderly ladies at the Home for the Aged and Infirm had no soft pillows. In the almshouse, inmates complained of fish “served usually in a dried-up condition and without gravy.” Embezzlement and peculation—or “honest graft,” as the Tammany men said—were as viral as the other ailments. In a single month, ten thousand pounds of bread, three thousand pounds of beef, and one thousand pounds of mutton had to be marked down simply as “not accounted for.” In the morgue, keepers sodomized the corpses.

Kingsbury was responsible for the largest social welfare system in the United States. New York City housed and fed one hundred thousand children, which was one third of all the publicly supported minors in the nation. The municipality paid more for its orphans than most states paid for their university systems. During his first days in government, Kingsbury toured all the many institutions of his magistracy. Not content to follow guides on sanitized inspections, he could appear at any odd hour. He wandered “in the dead of night through the hospitals where these poor people lie suffering, frequently on the floors and packed so close as to make it most impossible to step between their prostrate forms.” He inspected “the foul smelling wards where little children—sick children—sleep, two in one little crib.” He watched “the feeble-minded asleep in beds crowded so close these helpless creatures must crawl over the foot to enter.” He tiptoed over the roaches in an asylum on Staten Island. Then, back at home after these Bedlamite visions, he dedicated the remaining “wee small hours” to researching the history of his bureau, tracking the development of the city’s welfare facilities, sketching designs to help the helpless creatures for whom he was now responsible.

THE GALE HAD exhausted itself by the morning of January 13, but temperatures were falling toward zero. For the first time in three years, the Great South Bay froze over; ice encased the shore of Long Island from the Rockaways to Shinnecock. Telephone wires grew brittle and snapped. Broken glass crunched on the sidewalks; boarded-up windows became “so common a sight as to escape comment.” The Municipal Lodging House was overwhelmed and police considered converting their precinct buildings into temporary shelters. Kingsbury and Mitchel debated a plan to transform Madison Square Garden into a massive dormitory: “The suffering among the poor was the greatest in years and all agencies of relief were taxed to their limit.” Six people died as a direct result of the cold; scores more were hospitalized with frostbite. Dozens of fires disturbed the evening as families in unheated tenements burned anything available to generate some warmth. At midnight, temperatures dipped to four below zero, the coldest mark of the century.6

Ten more died the next day. Already undernourished and unhealthy, they no longer possessed the stamina to resist the cold. The city veered toward catastrophe and the Mitchel administration faced its first emergency. Tammany leaders had been able to improvise solutions. When storms came, thousands were crammed into saloons or meeting halls. Unemployment and homelessness were ward problems, resolved through handouts, favors, personal connections—or simply ignored. But the reform government couldn’t backslide into these old folkways. Progressive methods were required, and Commissioner Kingsbury had to provide them. He began with the worst abuses. Touring the moored ferries, seeing “the prostrate forms of homeless men strewn over the deck of the boats … huddled like hogs on the hard floor, and smelling worse than any hog-pen could,” had shocked even his toughened sensibilities. By the night of the fourteenth, he had enclosed an open-air pier and imported hundreds of additional cots. More than that he could not accomplish alone.

On January 16, the mayor attended the theater. Afterward, he was driven to East Twenty-fifth Street, where Kingsbury was waiting to lead him and Katharine Davis, the new commissioner of correction, on a tour of the Municipal Lodging House. For Mitchel, these occasions usually ended with a headache. They passed through all six floors, beginning around midnight, when the dormitories were filled with sleeping men. “Others, awake, sat up and looked hard at the Mayor as he made his way among the long rows of cots. The Mayor smiled at those who spoke to him, but addressed none of them.” In a dinner jacket, silk hat, and overcoat, he was profoundly uncomfortable and out of place. Ms. Davis, who had superintended the women at Bedford Hills prison for years, was more at her ease. As the elevator opened at the basement, Kingsbury stepped out first. The others started to follow, when suddenly he turned and rustled them back inside. They had accidentally arrived at the shower room, and it was in use. Luckily, the mayor’s—and Ms. Davis’s—dignity had been preserved.

Distasteful as it had been—and if not for Kingsbury’s sharp reflexes, it could have been much more unfortunate—the experience prompted Mitchel toward intervention. “Times are hard,” he proclaimed, “and the city should meet the situation.” More soup was to be distributed. A new municipal employment agency would link jobless men with vacant positions. Statistics would be compiled. “Above everything else I believe that it is important that we should not become panicky,” he said. “We must be optimistic and go right ahead buying what we need and giving employment so that these conditions will improve as quickly as possible.”

UNFORTUNATELY FOR THE administration, goodwill alone could not address these problems. A condition of “industrial leanness” affected the entire country. Everyone remembered the panic of 1893, when prosperity had “collapsed like a house of cards,” and the winter of 1908, which had seen “thousands and thousands of people out of employment.” It appeared that 1914 would be as hard or worse. Kingsbury’s own Association for Improving the Conditions of the Poor, “an old and conservative organization,” estimated 325,000 jobless men in New York City alone. Nationwide, the total approached three million; more than one third of all employees were out of work or laboring part-time. Distressing reports arrived from every state:

Kalamazoo, Mich.—A thousand men idle; works closing down.

Pottsville, Pa.—Ten thousand men of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Co. in the Panther Creek Valley have been laid off.

Washington, D.C.—With the completion of the Panama Canal, about 30,000 workers, a large number of them residents of the continental United States, will be out of employment.

Joplin, Mo.—Two thousand men in the Joplin zinc district are reported out of work.

Schenectady, N.Y.—Three thousand employees of the General Electric company have been laid off till spring.

Pendleton, Ore.—Farmers are furnishing meat for the hundreds out of employment in various small cities near here. Twelve hundred rabbits were contributed in one day.

Los Angeles, Calif.—Mrs. Mary E. Erickson, a widow, out of work and threatened with starvation, threw a brick through a plate glass window so she might be arrested and given food.

But to some, the weather made for a charming diversion. At Pocantico Hills, Junior and his wife had awakened “to find five inches of snow on the ground and every twig of every tree and bush beautifully covered with pure white snow … the picture from every window was simply like a fairyland.” In New York City, during the most frigid moments of the gale, some wealthy residents had “laughed at the weather and all its works” by strapping into their ice skates and tangoing across the marbled surface of Van Cortlandt Lake in the Bronx. As they danced, others were freezing. Of the dozen or so fatalities that week, one in particular embodied the iniquity of suffering. On January 13, a socialite rode to a Carnegie Hall concert. While she was inside, her chauffeur sat behind the wheel in the open cab of her limousine. Two hours into the performance, a policeman suspected he had fallen asleep and tried to nudge him awake; the chauffeur slumped forward in his seat, dead from exposure.

For revolutionaries, such incidents presented an opportune crisis. Nothing radicalized the working classes like a business panic. “At Rutgers Square, at Tompkins Square Park, in Mulberry Bend, almost anywhere in the tenement districts,” recalled a young radical, “a few minutes of speech-making would draw a thousand people together.” Pointing out that Congress’s new billion-dollar budget had failed to allocate a single penny to “aid the out-of-works,” the Socialist Party offered a platform of jobs bureaus and government relief through public projects. Anarchists scoffed at such reformism, urging direct action. “The problem of unemployment cannot be solved within the capitalist regime,” Alexander Berkman noted. “If the unemployed would realize this, they would refuse to starve; they would help themselves to the things they need. But as long as they meekly wait for the governmental miracle, they will be doomed to hunger and misery.”

Wealthy residents taking the opportunity to ice tango on the lake at Van Cortlandt Park.

The suffering had forced people to attend to questions that they otherwise might have ignored. For the first time in years, even influential professionals were discussing unemployment, lecturing on the subject, offering advice. When Mayor Mitchel appealed to the public for suggestions, the responses flooded first his office, and then the Department of Charities, so that Kingsbury—who was already holding daily staff meetings on the question—had to request that future letters be forwarded to the commissioner of licenses.

As yet everyone was dictating to the unemployed; no party or group had emerged to speak on their behalf. One potential candidate, the American Federation of Labor, the most powerful association of working people in the country, exhibited scant interest in the task. The organization favored skilled workingmen; it had no place for factory drones, let alone the homeless or jobless. It claimed two million adherents in all regions and industries. But they were sundered into hundreds of competitive subdivisions. In 1913, the A.F. of L. consisted of 110 national and international unions, 22,000 locals, five departments, 42 state branches, 623 city central unions, and 642 local trade and federal labor unions. Organized by trades, the separate units could be insular and competitive. A major industry, such as railroads, could easily be partitioned into a dozen distinct craft associations and brotherhoods, each with its own ambitions and interests. Brakemen, engineers, and conductors thought of themselves as brakemen, engineers, and conductors, not as a unified group of workers with a single set of needs.7

Since the federation was not interested, that left only one group with the potential to transform the disorganized and destitute into a militant and coherent force—an organization for which unity was a watchword, that insisted upon local leadership and total inclusiveness. For a decade, the Industrial Workers of the World—or Wobblies—had pushed “straight revolutionary workingclass solidarity.”

The Wobblies’ membership totaled about 1 percent of the A.F. of L.’s, but they offered “One Big Union” of all the workers, were more welcoming to women and minorities, and had long organized conference committees for the unemployed. While the craft unions focused on workplace issues “pure and simple,” the I.W.W. saw these gains as the first step toward industrial democracy. “The final aim … is revolution,” one leader explained. “But for the present let’s see if we can get a bed to sleep in, water enough to take a bath and decent food to eat.” This vision transformed the tiny, impoverished, anarchic I.W.W. into a looming menace. Capitalism could survive if the Pocketknife Blade Grinders’ and Finishers’ National Union won a pay increase, but the fulfillment of the Wobbly dream would mean revolution. “Organized a little we control a little,” they liked to say, “organized more we control more; organized as a class we control everything.”

The Industrial Workers of the World had been founded in the western timber and mine lands, but most of its victories were urban. It had waged free-speech fights in Denver and San Diego, had organized a triumphant strike versus the textile masters of Lawrence, Massachusetts, and its long battle against the silk lords of Paterson, New Jersey, right across the Hudson River, had just ended. But the Wobblies had not fared well in Gotham itself, and national leaders were grumbling. Big Bill Haywood, the union’s most notorious spokesman, was eager for anything that would make “the town rise out of a stupor.” And other organizers asked, “Why has not the I.W.W. a stronghold in the greatest industrial center of this country, New York City?”

The metropolis contained several chapters, including Local Number One, but the meeting halls on Grand and West streets were somnolent. “Are they alive?” the leaders wondered. “No—the most of them fell asleep.” The problem, reported the official newspaper, Solidarity, was solidarity. Meetings were disrupted by discussions “of a purely theoretical nature,” and the entire area had become “afflicted with internal discussion.” Sections were “worried into a state of inanition” by debates between political actionists and antipolitical actionists, centralizers and decentralizers. Eager recruits who had joined to accomplish “effective, constructive work” discovered an atmosphere of constant “peevish, petulant criticism” and soon dropped out.

Still, many chose to be optimistic. If only you could “fight capitalism as well as you fight one another,” a member wrote to his comrades, then the I.W.W. would have already achieved its goals. It was time to “drop all hobbies and get into the harness” for “one big united effort!” A drive to organize restaurant and hotel workers was producing results. And the unemployment situation offered new chances for agitation. “Let us fight against capitalism,” wrote a national leader, “as we never fought before; and make the year 1914 glorious in the history of the SOCIAL REVOLUTION!”

The local ennui had not affected Frank Tannenbaum’s faith in the One Big Union. On the contrary, he “took interest in nothing but the I.W.W … read nothing but of the I.W.W … considered all speech futile which did not ostentatiously expound the unexcelled virtues of the I.W.W.” Nineteen years old, he had worked as an omnibus, washing dishes, in a luncheon club in Wall Street until late in 1913, when he—like so many others—had lost his job.8 Unable to pay for his room at the Sherman Hotel, in the Bowery, he had taken to sleeping in parks and lodging houses. Increasingly, he found himself in “close contact with the unemployed in New York City.” He watched “men pick bread out of garbage barrels and wash it under a street pump so that it might be fit to eat.” At night he sat with them, “closely huddled together, with their collars drawn up, their hands in their pockets, and heads tucked in to keep as warm as the conditions permitted.” He joined them in their search for a job, standing in line for advertised positions, and never coming close to reaching the window. “Looking for work and not finding it,” a former stonemason told a reporter, “is the hardest work I know.” These were the same people the papers decried as shiftless loafers, profiting from the city’s generosity. “It’s a lie,” Frank muttered as he read such stories. “A d——d lie.”

He had been born in Austrian Galicia in 1894. Ten years later, his family steamed to the United States. Borrowing money from relatives, the Tannenbaums purchased an abandoned farm near the town of Liberty in the southern Catskills. But rural life was “not all honey and flowers, bluebirds and green grass.” The apparent freedom of outdoor work tangled with orthodoxy and constraint, “poverty, ignorance, loneliness, and narrowed and blighted lives.” Frank felt himself stultifying, and while still a youth he fled the feudal relations of peasant life for greener pastures in the Bronx.

Frank Tannenbaum.

Tannenbaum had suffocated on the farm, but in the city he remained “restless, dissatisfied.” He had come to try and educate himself; his ambition was to earn a high school degree. But conditions did not allow it. He had to find employment to support himself. Working as an elevator operator, he read Plato between ascents and descents. All he knew was that he had to keep learning; he felt “a sort of inarticulate hunger, a longing for books.” He took close notes on all he read, and then, at night, he and his friends would walk across the Brooklyn Bridge carrying on passionate arguments about their conclusions. He found his greatest fulfillment in politics. His “best friends and his bitterest enemies” were the comrades in I.W.W.’s Local Number 179. It was “a socializing vortex” of passions and disputes, committee meetings, “picnics, parties, benefits and funerals.” When he wasn’t down in the hall on West Street, he was uptown with the anarchists at the Ferrer Center, their community school and meetinghouse. He came to know Berkman and Goldman, impressing them with “his wide-awakeness and his unassuming ways,” and aided in the chores of publishing Mother Earth.

He was quiet and conscientious. Neither he nor anyone else could ever remember him being impolite. With tousled black hair under a floppy woolen cap, a tight smile, and no trace of a beard, there was little to distinguish him from the city’s other youths. And his ordinariness was agony. His aspirations mocked him. “What are you doing? What have you done? What are you planning?” These questions he constantly asked himself. Interacting with the elders of his movement, he was self-effacing and deferential, but he persecuted his peers with propaganda. Those who disagreed with him “were stupid, ignorant, useless people.” He “scorned the Socialists, the American F. of L.,” and “despised their methods.”

According to a friend, Frank possessed “three predominant faults, namely 1. a noticeable desire to become popular 2. self conceit 3. too much of the ego.” But he didn’t see these as flaws: Focus and determination were necessary for success. “Personally ambitious, desirous for place, acknowledgment, and honor,” he found, through the I.W.W., “a constant battleground for the attainment, as well as expression, of these ends and motives.” He helped to organize restaurant workers, contributed fifty cents to the legal defense fund, and volunteered as secretary for the Industrial Union League. But so far he had done nothing memorable; he had not distinguished himself. In the evenings, he strategized with friends, drafting elaborate plots to further the cause of industrial democracy—and, incidentally, to force the name Frank Tannenbaum into the public mind.

* * *

THE NEXT STORM rolled up along the tracks. Following the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe lines from New Mexico, it dropped ten inches of snow in St. Louis on the morning of February 13. Three thousand men dug out the Union Station yards, but the switches were frozen and traffic stopped moving east. The weather surged forward, tracing the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks and the New York Central System, through Cincinnati, eight and a half inches; Wilkes-Barre, twelve inches; Scranton, twenty inches. Depending on one’s location, it was the worst storm of the year, of the past three, the most snow seen since the “Big White Christmas” of 1912, the biggest in five years, the most destructive since the Great Blizzard of ’88.

The first flakes that fell on Grand Central Terminal, in the early evening, were “small and dry and were blown about.” At midnight, the storm grew serious. By one A.M., “snow was coming down in blinding swirls.” Plows, sand, and channel cars couldn’t keep the transportation network running. Streetcars and elevated trains were blocked, autos stalled as “engines tore their hearts out trying to buck their way through drifts, and tires wore to ribbons with mileage that could hardly be measured.” Dead machines clogged the streets. In the railroad stations, people escaping the weather mixed with those waiting for friends and relatives to arrive. The Twentieth Century Limited, the Chicago Express, and everything on the Lackawanna lines were hours late. Some companies doubled up their engines, but trapped locomotives blocked tracks throughout Pennsylvania and across the Mohawk Valley. The Erie Railroad was “badly demoralized.” The Albany Local was “annulled.” Ten inches of loose and powdery “dry sleet” fell in the city, making walking “difficult and treacherous.” And then the tempest passed on—along the New York, New Haven, and Hartford tracks—toward Maine.

ON THE MORNING of February 14, during the storm’s hardest anger, unemployed men, boys, and one woman, “with collars turned up and hands thrust deep in their pockets as the drifts formed about their feet,” queued out front of No. 27 Lafayette Street. Inside, the staff completed its final preparations to convert a giant storeroom into the city’s first municipal employment bureau. The mayor was certain that this new institution could lessen the muckery and muddle that lay behind the labor crisis. There were 725 licensed job-placement agencies in the metropolis, but their efforts did not coordinate. Together they had only managed to fill 58.5 percent of all available positions. More than ten thousand jobs remained empty as a result of the scattered system. “The figures show conclusively,” Mitchel argued, “the need for a clearing house, so that in some place in the city a man or woman looking for a job can find out whether a job he or she can fill is available anywhere in the city.” At eight A.M., the doors opened, and the line of potential workers slogged inside. The examiners took down their pedigrees and the names of their most recent employers. The results revealed a hearty crowd of chauffeurs, clerks, carpenters, and bakers. “There wasn’t a single man among them,” a reporter thought, “who didn’t look as if he had something to offer in return for employment.” And, as it happened, New York had suddenly acquired the need for such a crew.

Ten inches of snow lay atop three hundred miles of avenues and boulevards in the greater city. The sanitation department had twenty-three hundred full-time street cleaners, sweepers, and drivers. In a big storm, that number could be doubled with auxiliary helpers hired through private contractors, but even this force could remove only an inch of snow per day. Barring a thaw, that meant it would take more than a week to clear the streets. In the meantime, the fire hydrants were blocked and streetcar service was in disarray. Extra hands were urgently needed, and the administration knew just where to locate them. On its first day of operation, the municipal employment bureau assigned 570 men to shovel snow, at a salary of thirty-five cents an hour. A temporary solution to the jobs crisis, certainly, but nevertheless the combination of labor and laborers had the aspect of providence.

February 14, 1914.

The slush froze hard. By the afternoon, men were hacking at ice, stretching to lift their loads onto small, high carts and losing half a batch with each shovelful. After two days, with progress finally apparent, another flurry added a new layer of a “fluffy sort” of flake, and everything backed up again. Fifteen inches—three million cubic yards—of snow covered the streets. Twenty thousand men were now at work, and even Mayor Mitchel plied a shovel.

Up in Tarrytown, Rockefeller Senior’s golf course lay beneath two feet of snow. He had to keep himself—and a hundred employees—busy by digging out the paths around his house.

After a week, even the city’s main thoroughfares remained deranged, the ice skaters had discovered new diversions, and reserves of good humor had emptied. “As a comedy of inefficiency and waste and feebleness, nothing could equal the scenes of overcoming this blockade of New York’s streets,” griped the World. “It is Lilliputians wrestling with a native of Brogdingnag. It is an army of moles working at a mountain.”

Thirty-five cents an hour was no fortune, considering the severity of the work. And that old foe, graft, incised deeply into even this meager sum. Each person sent from the employment bureau was directed to a private contractor who took twenty-five cents off the top plus a dime to hire the shovel. After an eight-hour day, and another nickel for the foreman, a man might have a dollar left. But he didn’t get a dollar, he got a ticket, which he could use only at a particular saloon. There he was charged 20 percent to cash the thing and was forced to buy a drink. “Well, you are faint, frozen, trembling with weakness and fatigue,” a snow digger explained:

You are only human. You may take two drinks, three drinks, four—and your body has paid the toll of toil and you are dazed with bad whiskey that saps what little strength and resolution you have left. The next day, sick, aching, empty, you haven’t a penny, you haven’t any strength, any heart or any hope—you are only sick, aching and starving; your feet are bruised and wet and cold, your dirty clothes cut and chafe you, the grime and sweat is caked on you—you are a dead man who limps and aches and whimpers!

It only took a few days before protests began to disturb the business of the municipal employment bureau. Sick of shoveling, the men “became obstreperous,” and the director called in police reserves to drive them out. Two hundred marched from the exchange to City Hall, denouncing a system that identified a quarter million men out of work, offered a few of them pennies to perform back-destroying labor, and considered the problem solved.

THE LAST OF the snow was gone, washed into the sewers by a blessed rain, when on the morning of February 27 hundreds of delegates crammed City Hall for the first national conference on “The Jobless Man and the Manless Job.” Representatives from charity groups in Chicago, Milwaukee, London, and dozens of other municipalities were on hand to share their experiences. John Adams Kingsbury sat on the dais, and Mayor Mitchel offered the opening statements, extolling the success of his new employment office, suggesting mild remedies, cautioning against drastic measures. That evening, the conference held a second session at Cooper Union. The tone became less reserved. There were half a million vagrants and beggars in the United States, a delegate claimed, and each year they caused $25 million in damages to property. “We must do something,” cried another. “We cannot let things go on as they have been doing.” During the general discussion, an audience member asked William Howard Taft what advice he’d give an able man looking for work; the former president shook his head and replied, “God knows.”

Outside the hall, a massing, angry crowd gathered to listen to more constructive suggestions. The principal speaker, a nineteen-year-old boy in a worn-out cap, had a plan. “New York City is full of churches,” he explained. “We will march to one of them and go to bed. If they don’t like it, they can lock us up and then we can sleep in jail. We will march to the Court Houses and they can lock us up. We must get some food, too. In this city there is plenty of bread and provisions. We have a right to as much as we can eat.” And with a thousand men behind him, he led his army of unemployed toward the Old Baptist Tabernacle on Second Avenue. The next morning, New York City would finally read his name, or at least a version of it: “Frank Lenebaum.”