“If the ladies will form in line on one side of the room and the gentlemen on the other,” the instructor began, “I will explain the rudiments of the steps which make up the new dances.”

Fifteen men in tuxedos and fifteen married women ceased chatting and parted to opposite ends of a small ballroom in the Plaza Hotel. It was a Saturday evening, and they—like hundreds of their peers across the city—were here for tango lessons.

The pianist played a few notes, slowly, so that the teacher—a veteran of the Winter Garden and the Folies Marigny—could explain the simplest moves. First came the hesitation. He counted as he demonstrated, “One, one-two-three, one-two!”

“Oh, isn’t that pretty?” exclaimed one of the students.

The ladies and their partners pantomimed the steps separately. “Feet together!” he called out. “Ladies forward with the left … Balance!” The women were quick learners, the men not so quick. Among the latter, one appeared especially befuddled. After a series of missteps, he finally stopped completely, confessing, “I don’t quite get that.” The instructor clasped the pupil’s hands and practiced with him a dozen times, very slowly, counting aloud: “One, one-two-three, one-two.”

When at last all were ready, the piano played “Nights of Gladness,” and the couples were permitted to attempt the hesitation together.

“This will be an easy one,” the instructor assured his students, as he displayed the next step. Most took to it. The awkward beginner concentrated hardest. Whenever he did something wrong, he would pause, count earnestly and aloud, and repeat the move again and again until he was satisfied.

Then, during the hitch and slide, he stumbled and stopped completely. “I don’t quite get that,” he said again. Once more the master clasped his hands, danced him round till he had the knack, and returned him to his practice partner.

Afterward, the teacher asked one of the onlookers, “Who is the young man who asks so many questions?”

“Why, don’t you know?” came the answer. “That’s young Mr. Rockefeller!”

JUNIOR MIGHT NEVER become the most agile dancer, or for that matter the sprightliest wit, the wisest commentator, the most inspiring orator, the best good fellow. In fact, nothing came easily to him. What he lacked in instincts, however, he made back through discipline, pursuing each task with a rapt focus that was utterly unself-conscious. “The annoyances, the obstacles, the embarrassments had to be borne,” he believed. Anything that stood in the way of success “became merely details.” It was this determination that had steered him to remain on the board of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company until it turned a profit. It guided his philanthropic work, inured him to the criticism and ridicule of public life. I don’t quite get that, he’d ask his advisers, attending to their answers until he was confident in his position. And it was effective. Junior made great progress, even at the waltz. “He ‘scissors” and ‘cortezes’ like an adept,” the instructor raved at the end of the lessons, “he has every little dip and twist at the tip of his toes—it’s a pleasure to watch him spinning about the ballroom, light as thistle-down.”

Junior was again immersed in reform work. “The first four days of this week were consumed with all day conferences,” he complained to his mother after sitting through meetings for the Rockefeller Foundation and the General Education Board. The new report from the American Vigilance Association, an antiprostitution society, had just arrived. He took this work more seriously than any other; in December he had donated $5,000 to the group, and he personally supervised its team of undercover agents, who infiltrated the city’s brothels gathering information on the prevalence of the Social Evil.

The latest revelations were as shocking as ever: New York remained a city of sins. To ensure that the proper officials were made aware of its findings, Junior had the document forwarded, through his Bureau of Social Hygiene, to the mayor and police. Wanting future accounts to be even more persuasive, he asked that the next installment be as far-reaching as possible. “It therefore should cover saloons, with their rear rooms, disorderly cafes and other places where vicious people congregate,” he wrote to the investigators. “In view, therefore, of this broader scope of the inquiry, you may think it wise to put another man or two on this month.”

Few of Junior’s good works meant more—or had caused him more “nervous depression and despondency”—than the Young Men’s Bible Class, which he had led, off and on, at the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church for the previous fifteen years. Teaching religion to others had helped him elaborate his own theology of discipline and service. He credited it with guiding his decision to retire from business, and it was his best avenue for interacting with people outside of work and family. But the effort of preparing his speeches had many times threatened to overwhelm him. Three nights a week he would enclose himself inside his study to write out meticulous outlines on index cards. Then, on Sundays, he would pass along his insights. Recently, in a talk on “Fixing Life Standards,” he had urged temperance in food, work, exercise, pleasure, and drink. “If a man is unwilling to do small tasks and do them well, he ought not be permitted to do big tasks,” Junior had said, “and if he is permitted mistakenly he is most certain to fail.”

Under his leadership, the class had grown to hundreds of students. And if some of these merely hoped to benefit from his acquaintance, many had been impressed by the patent sincerity of his lessons. Guest speakers had included Andrew Carnegie, Booker T. Washington, and Mark Twain. He invited the members to his home, gave them individual attention, and sponsored annual banquets. Whatever lengths he went to, however, the press and public were quick with malicious comment. “Every Sunday young Rockefeller explains the Bible to his class,” Twain remarked. “The next day the newspapers and the Associated Press distribute his explanations all over the continent and everybody laughs.” Condescending headlines—ROCKEFELLER ON LOVE: SAYS MOTHER’S IS NEXT TO GOD’S, or ROCKEFELLER ON RICHES: WEALTH DOES NOT GIVE HAPPINESS, SAYS BIBLE CLASS LEADER—were bad enough, but the implication that his religion was little more than hypocrisy was far worse. “With his hereditary grip on the nation’s pocketbook,” one newspaper complained, “his talks on spiritual matters are a tax on piety.” Junior bravely kept at it, in spite of the humiliation. And by 1914 this determination had finally earned him some respect. “You have borne all the criticism and ridicule that is necessary,” his wife reassured him, “to let the world see that you are sincere.”

On Sunday, March 1, as yet another incapacitating blizzard reached the city, Junior prepared to lead a Bible class at the Calvary Baptist Church on Fifty-seventh Street, a couple blocks from his home. His father, who had recently come east, motored down from Tarrytown, a drive that took an hour and a half in the rising storm. In their reserved pew, at the center of the second row, the two Rockefellers sat together—Senior in a fur coat and “a pair of old fashioned ‘galoshes’”—while several nearby benches remained deserted. Few others had been willing to brave the weather to hear the sermon.

In the late afternoon, as Junior was conducting his class, the Calvary caretaker placed a frantic call to the Forty-seventh Street precinct house: He had heard that the Industrial Workers of the World were coming, and the church needed protection. A guard of reserves hurried over. As congregants arrived for the evening lecture, they passed through a barrier of police guarding the Gothic portico. At the end of the night, as Junior stepped down into the snowy streets, the officers were still there, stomping and shuffling to keep warm after a tedious watch. All across Manhattan that night, policemen promenaded outside of frightened churches. The I.W.W. was on the march, and no one knew where the menace would appear.

BY EIGHT P.M., in fact, they had arrived at Washington Square: a straggling column of nearly a hundred unemployed men with Frank Tannenbaum in the vanguard. “Plodding through the thick slush in downtown streets, with sharp sleet cutting into their faces,” the troupe passed beneath the marble arch and paraded up Fifth Avenue. A few blocks north, at Eleventh Street, there appeared the Tiffany windows of the old First Presbyterian Church, “shining through the snowflakes” like welcoming beacons of relief. The minister was preaching “Redemption” to a sparse audience. The main doors crashed wide and in stepped Tannenbaum. Footsteps ringing on the stone floor, the intruders tracked dirty snow down the aisle. They sidled noisily into the front pews, gaping and leering at the gasping congregants, many of whom “were highly excited and apparently half inclined to flee in terror from the horde of ragged and wild-eyed invaders.”

The reverend had stood dumbfounded as they had entered. It was the Industrial Workers of the World—and they had chosen his church. “There can be no question of our sympathy toward you on such a night as this,” he stuttered, at last, “and no question but that we will give you whatever aid you need.”

“I’d like to say a few words,” said Tannenbaum, rising from his seat.

“You may, if you say nothing to create disorder in this sacred place.”

“Well,” he said, “we’re cold and we’re hungry and we’re going to sleep in here where it’s warm.”

“I am sorry that I cannot invite you to do that.”

Then members of the mob leapt up and began to yell.

“You’ll have to club us out!”

“We’re going to camp right here!”

“Yes, don’t worry. We’ll take all the responsibility off of your hands.”

Fearing a riot, the pastor beckoned Tannenbaum up to the pulpit and offered twenty-five dollars for the men to pay for food and shelter, if they’d only agree to leave quietly. Frank took the money and marched his triumphant mob back through the aisles. As they went, their roar of satisfaction “shook the rafters of the vestry.” But in the lobby the sight of a file of policemen quieted them down. The cops had been called during the confrontation. They had their nightsticks drawn; all they needed was an excuse. The unemployed crept past the menacing cordon, just a little chastened.

Out in the “miserable, windy night,” they feasted in a Bowery restaurant and then tucked themselves into beds at a nearby hotel. The money was spent down to the last dime.

THIS WAS THE third straight night that Tannenbaum had trespassed against a city church. By the next morning, March 2, the clergy had split in its reactions. Most were outraged. For years they had complained of the drop in churchgoing, but the I.W.W. solution was not to their taste. Several ministers responded to the threat by canceling their evening services, preferring no prayer at all to the possibility of an appearance by the unemployed. A few offered their support, embracing the challenge of caring for the needy in a desperate season. In that morning’s World, the pastor of St. Mark’s-in-the-Bouwerie had even invited the homeless to shelter in his chapel. Tannenbaum decided to accept his offer.

That evening he led more than a hundred followers out of Rutgers Square, one of the few slashes of open space amid the crush of East Side tenements, which served as a meeting place for radical gatherings.9 As they passed others along the way, the men called out, “Come on with us and get free food and lodging,” so that their ranks had more than doubled by the time the parish doors opened for them at St. Mark’s. Church-women beckoned them in from the darkness to a large, brightly lit chamber set up with two long tables loaded with coffeepots and piles of bean sandwiches. The men thronged inside, removing their hats, joshing each other. “The great fireplace was piled with burning logs,” a reporter wrote, “and for a moment this aimless crowd seemed at peace with all the world.”

Frank devoured a sandwich and waited for the others to finish eating before he rose to speak. “We want work, but we will not work for 50 cents or $1 a day. We want $3 a day for an eight-hour day, and any man who works more than eight hours scabs it on us,” he said. “They tell us to go to the Municipal Lodging House, but I tell you that it is not fit for a dog to sleep in. Let Kingsbury sleep there. We are going to establish a boycott on the Municipal Lodging House so that no man out of work will go there.”

All the time he was talking, more men were arriving; by eleven P.M., the newcomers had filled a second room. Men snored in their chairs by the fireplace. Others stretched out along the floors. All was quiet as the reverend made his final inspection of the night. In the morning there was coffee and eggs, and the men scattered in search of work, leaving a few volunteers to tidy up and shovel snow.

The Bowery breadline.

Frank woke with the others, and then headed to 214 West Street, the Wobbly headquarters on the waterfront, to read about himself in the papers. Photo insets showed his wavy curls and round cheeks. The newsmen who had once ignored him were now insatiable for answers. “Who is this young Tannenbaum?” they asked. “Where did he come from? Who are his parents, what his boyhood environment? Is he normal or abnormal mentally and physically? What started him on the program begun a few nights ago when he and his ‘army of the unemployed’ began to raid churches?” Was he “a fanatic or an extremely able propagandist of some special order,” was he even a leader at all, or “a convenient catspaw for the invisible leadership which is the inspiring and directing force of the I.W.W. activities”? Reporters competed now to pen vivid portrayals of him. “His black hair blown half across his face, his jaw set and his eyes agleam with determination …” one passage began. He was often misquoted, maligned, and misrepresented, but his name was in the headlines every morning. And no one misspelled it anymore. “Now, what is the program, the idea, the definite plan proposed by this smooth faced, slender stripling?” asked the Sun. “Why, merely to take possession of New York—that is all.”

Each night he told his men: We are not slaves. We are not accepting charity. What we’re getting—they owe it to us. Not once—despite what the newspapers said—not once had he raised his voice in anger, preached anarchy, or incited violence. Newspapers called them a “ragged regiment,” a “mob.” Well, they might be a little rough, but he had never felt love the way he did when they were all camping out together at night. Watching them eat a hot meal served on clean dishes in a warm room—it was the most religious thing he’d ever seen. The city knew him now as the “Boy I.W.W. leader,” and Frank was happier with that job than with anything else he could think of. He wouldn’t give it up for anything—not even for a place in President Wilson’s cabinet.

* * *

IT WAS SNOWING that week in Washington, D.C., as well, but inside the Willard Hotel on F Street, it smelled like spring. The foyer was bedecked with flowers: pink azaleas, Richmond roses in crystal vases, tulips and hyacinths in gold baskets. Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet members planted themselves amidst this garden in anticipation of their leader’s arrival. Around eight P.M., the White House motorcade appeared and the president hurried his two daughters through the weather into the comfort of the parlor. It was March 7, the one-year anniversary of the administration’s first cabinet meeting, and everyone felt like celebrating. After collegial greetings, the guests passed into the dining room for supper. “There was no set program,” reported the Washington Post, “spontaneity being the keynote of the evening.” The courses progressed, accompanied by enthusiastic toasts and a serenade by the Marine Band. All in all, it was “as informal as an occasion may be at which the President of the United States is a guest.”

For the previous several days, newspapers had been offering end-of-year retrospectives on the administration’s progress. Congress had continued in session for eleven of the twelve months of its tenure, and the record of legislative accomplishments was unimpeachable. “It has been a year of incessant activity and of substantial achievement,” the New York Tribune exulted. “Mr. Wilson has already written his name high on the list of the Presidents who have done things.” He had shown himself to be an able executive, a dynamic speaker. “He has always appealed to the ‘intellectuals,’” conceded editors at the Outlook. “He now appeals to very practical persons and to the man-in-the-street.”

If these glowing assessments, along with “an elaborate menu with the usual liquid accompaniments,” heightened the conviviality at the Willard Hotel, the president also shouldered some private cares. His wife, Ellen, had felt her health decline alarmingly since the start of the year; having already endured a succession of illnesses, she remained bedridden and in pain after slipping on the polished White House floor a few days earlier. Also, though no announcement had yet been made public, Wilson had just learned that his youngest—and favorite—daughter had broken with a longtime fiancé and was now engaged to marry his own secretary of the treasury, a man more than twice her age.10

And then there was foreign affairs, where a looming crisis threatened to subvert all the administration’s domestic gains. In February 1913, weeks before Wilson had even taken office, a Mexican general, assisted by agents of the U.S. embassy, had assassinated the progressive president of that country and then claimed the office for himself. American entrepreneurs welcomed the change; the new leader was the sort of man they enjoyed doing business with. He had no notion of redistributing land to the peons or of nationalizing the oil reserves. Most of the world’s nations had immediately recognized the fledgling government, but Wilson demurred, refusing to partner with the blood-soaked regime. Political turmoil descended into civil war as various insurgent groups took up arms against the illegitimate government in Mexico City. Investors panicked. War correspondents wired back tales of atrocity and outrage.

The president faced a diplomatic quandary. He could relent—as American business interests were howling for him to do—and belatedly acknowledge the ruling clique, or he could throw his support to the rebels, a disparate array of revolutionaries and banditos. Neither side lived up to his high moral standards for governance. It was more or less impossible to differentiate between them. “This unspeakable conflict is not a political quarrel, but a mere fight for power and plunder,” a reporter wrote. “It is Jesse James against Tammany.”

Unwilling to adopt either faction as an ally, Wilson chose to remain aloof and hope the situation would resolve itself. Thus began a period of “watchful waiting,” which lasted throughout 1913 and into the new year. During this time, he had demanded the strictest neutrality, refusing to sell arms to either side and standing firm against ever-more-strident demands for action. When it came to foreign affairs, he was determined to be more than just a director of policy; he would be the self-appointed conscience-in-chief for the nation. But his rectitude did not impress the Mexican combatants, and procrastination was not a program. The president’s cool detachment looked like indecisiveness. Friends began to murmur. Opponents sensed weakness and moved to exploit it. Critical committee reports and resolutions appeared daily in Congress. “We have been informed by the President of the United States that the policy of ‘watchful waiting’ would bring peace results in Mexico,” a Republican senator had complained a few days earlier. Instead, Wilson’s inaction had “resulted in a ‘deadly drifting,’ if not in merely wishing.”

Finally, in early February, the president relaxed his position by lifting the arms embargo and allowing American firms to supply weapons to the Mexican rebels. If he had hoped this would bring a quick termination to the conflict, that wish was soon dashed. The insurgents had indulged in a spree of atrocities of their own, further eroding their standing as a potential ally in the cause of democratic progress. As March began, only one alternative remained. The United States could cease acting through untrustworthy proxies and involve itself directly. Publicly, Wilson still refused to consider any move toward invasion. At a White House press conference he reminded those “clamoring for armed intervention” to recall the sacrifice involved, urging them “to reflect what such action would mean to brothers, sons, and sweethearts.” But a subtle change had shifted in his stance. No longer did he dismiss outright the calls for action. The situation may not have warranted such a move just yet, but if the provocations continued the time might come to adopt “a drastic course.”

* * *

IN NEW YORK CITY, the longed-for thaw came on March 3, and—finally—the grimy ice began to yield before ten thousand shovels. Pedestrians stayed to the middle of streets to avoid the deadly icicles that “dropped tinkling to the sidewalks.” High-piled snow wagons creaked through the avenues, swerving between trolleys that were running again after days of inactivity. No one talked anymore about a coal shortage, or of milk and egg famines. The heaps of week-old trash began to smell. Stockbrokers, typists, and clerks resumed their commutes.

In the late afternoon, runoff from the remaining piles of gray slush coursed in dark streams through Rutgers Square. Scores of men hid from the wind in doorways; others drifted toward the plaza. By 6:30 P.M., when Tannenbaum paced decisively through the ranks, hundreds were waiting, drawn by the news of his successes. They cheered and gathered in close as he leapt onto the granite rim of the fountain to announce that he had arranged food and shelter for the night. Clambering down again, he shoved his charges into a column two abreast, snarling, “Get in line and be decent,” as they left the square and headed west on Canal Street.

Lower Manhattan, hectic with the evening rush, paused to stare at the parade. Thousands of office workers watched it pass; traffic locked up as it went by. “There was a prophetic, peculiarly, significant aspect in the entire affair,” an observer thought, “that caused many ordinarily indifferent to the pleadings of the poor to turn and watch the little procession until it faded away in the distance.” In the ranks some began to sing “Hallelujah, I’m a Bum,” till Frank told them to pipe down. And then they marched in silence toward the Bowery Mission, where more than a hundred men queued on a breadline.

“Is this the I.W.W.?” shouted someone from the sidewalk as they drew close.

“Yep,” came the response. “Come on along, we’re going to church.”

“Jump in, boys!” another marcher shouted. “Get in the real breadline and see what’s comin’ t’you.” Dozens of new recruits rushed to join the parade, leaving only a few grumblers behind to beg a handout.

Turning downtown again and now numbering more than two hundred, they arrived at the parish house of St. Paul’s Protestant Episcopal Chapel, at Broadway and Vesey Street, where women church workers passed around pots of coffee as well as platters of bananas and corned-beef sandwiches. “We are entitled to champagne, roast turkey and a shower bath,” Frank said this time.

Every one of us should have a room with a couch and all the comforts of home. Rockefeller and a lot of other people would break the law in a minute if they had to sleep on the floor. We are going to break the law and go to jail if necessary to get what we are entitled to. We are the workers of the world, but we can’t get work. I suppose I’ll be arrested before this is over. I expect to be, but I’d sooner spend my time in jail, where at least it’s warm and where there’ll be something to eat, than be put out in the cold without shelter or food or work.

The lights were put out at ten P.M, and the halls quieted down. Across the street, a dozen police officers hid in the shadows, away from sight. Plainclothesmen had been with the men right along—in the crowds at Rutgers Square, on the march to St. Paul’s—and their vigil continued still; the ranking officer, hoping for a chance to act, planned to wait throughout the night, “in case he might be needed.”

VACATIONING IN THE Adirondacks, Mayor Mitchel was snowbound by the blizzard. His staff could not reach him by telephone; downed wires left him stranded and helpless to intervene in the growing crisis. Without him, the Tannenbaum problem was getting beyond control. Four nights. Four churches. Clergymen panicked. Editorial writers apoplectic. While the mayor went ice-skating on Lake Placid, the unemployed had established “a condition of terror and brigandage” in his streets, and gangs of professional agitators were “terrorizing public assemblies from the Battery to Harlem.”

In the mayor’s absence, Commissioner Kingsbury had served as the administration’s voice on unemployment. And an overflowing font he had been, issuing contradictory statements, flashing from project to project, accomplishing naught. Labor conditions were “abnormal,” he confessed, but did not require converting the armories into shelters or opening the churches. “Such action,” he believed, “would only bring more unemployed to this city and further complicate the situation.” Only so much assistance could be offered; too much would foster indigence. “Relief, like cocaine, relieves pain,” he said, “but it creates an appetite.” The Municipal Lodging House had already received twice as many applicants as in any previous year of its existence. He had expanded the facility, and even if it still didn’t have enough beds, it offered every man a meal and “a more comfortable place to sleep than he can find in the basement of any church.”

Mayor Mitchel in the Adirondacks.

These were temporary measures. Lasting solutions would have to wait until the administration had a comprehensive, scientific understanding of “why some individuals become homeless drifters instead of capable workers”—and that would take at least two weeks. For fourteen straight nights, Kingsbury directed research experiments on the residents at the Municipal Lodging House. On March 2, at the very moment when Tannenbaum was leading his aching cold men into the cozy warmth of St. Mark’s chapel, the initial 143 subjects were being selected from the city shelter’s inmates. Thirty specialists—ten physicians, ten sociologists, ten psychologists—as well as a regiment of stenographers awaited in telephone-booth-sized consultation rooms. The human subjects were asked probing questions: Did you desert your wife? Have you ever been convicted of a crime? They were measured and prodded by the physicians, and required to recite the days of the week forward and backward. “When the work is finished,” Kingsbury promised, “we expect to know the who, the what, and the why of the unemployed problem. Then we will know just how the situation sums and we will know how to go about the work of devising remedies.11

But Kingsbury’s ideas were just exasperating now, his ruminations about as welcome as the incendiary speeches of the anarchists. His experiment had a touch of absurdity to it; not even the most committed social scientists really believed that a few questions to a random group of subjects could elicit any fruitful results. The editors of the New York Herald were just as sick of “sociological investigators” as they were of “professional agitators.” Radical critics joined in, too. “The great man in the City Hall investigates, investigates,” sneered the socialist Call. “Mayor Mitchel and Kingsbury are largely responsible for present conditions.” Big Bill Haywood, the leading national spokesman for the Industrial Workers of the World, stormed to reporters via telephone: “But they are in exactly the same boat with ex-president Taft. He said ‘God knows’ when asked what ought to be done to remedy conditions. These officials have made no provisions.”

It was not until March 4 that Mitchel’s overnight train finally sighed into Grand Central Terminal. In public he downplayed the Tannenbaum issue. “I don’t think that there is any situation,” he reassured reporters. “As a movement, I think it is played out. If it isn’t, we’ll deal with it, but there is no situation with a capital ‘S,’ as far as I can see.” In private, though, he conceded that action was necessary. Hauling his police commissioner, Douglas McKay, down to City Hall, he insisted on a firmer stance. Afterward, the chastened commissioner told reporters, “I will not stand for any high-handed measures by the I.W.W., or any other organization. As soon as they commit any act demanding police action I will be in a position to use the police.”

FRANK SET DOWN the morning newspapers on March 5, feeling like the hunt’s prey. They were after him now. The editorials bawled for blood, for his arrest, for the police to come and club him down. All week, he had felt those batons hovering. The cops had always been there, waiting, infiltrating, hoping to provoke some trouble that could justify his arrest. Of course, he had given them no excuse. It was against no law to point out the hypocrisy of church and government. Still, the master class would get him. He had always known how his protests would end. In the afternoon he met with Haywood, who couldn’t participate himself but who urged Frank to “keep up the damned agitation.” And that’s what he intended to do—but as he walked once again through the mired streets toward Rutgers Square, it was with the intuition of looming disaster.

The largest gathering yet awaited him. A thousand men, maybe more, applauded his approach, cheering again as he climbed the fountain. Interspersed amongst them, though, was also a large detail of police: detectives whose faces had grown as familiar as his friends’, plainclothesmen who stood out from the gray crowd, as well as blue-uniformed regulars who had never been more apparent. “I’m sorry for you fellows,” he called to them. “You are only slaves like ourselves.” But he knew it was vain to try and reconcile them; the grim cops stood unmoved, waiting.

Tannenbaum climbed down and ordered his men into ranks. He led them along Canal Street past the Bowery, walking quickly. He made no announcements about where they were going, and appeared to be deciding as he went. He turned north onto West Broadway; his followers stretched out over three blocks behind. The police detectives were right beside him, ready to react to whatever he did. He could just give it over for the night and try again some other time. But no, it was better to play it out, as Haywood had said, to “keep up the damned agitation.”

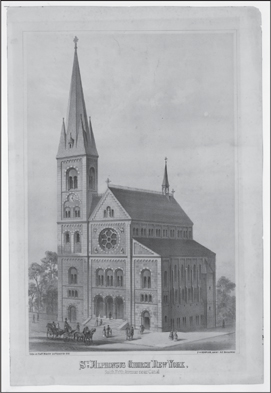

Halfway up the block, on the left, Frank’s eyes lighted on a church. Drawing level with the stone stairs, he turned without warning and ran up toward the doors. Two plainclothesmen had been marching with him pace by pace, twitchy and sharp for any movement he might make. When he reached the entrance and turned to face his men, the detectives were right behind. His parade had stopped, and the stragglers were still catching up, massing around the foot of the steps. The detectives urged him on, and Frank entered the dimly lit nave of St. Alphonsus’ Catholic Church. The policemen followed. The door closed behind them.

Inside, statues of the saints loomed by the doors. It was too dark to see more than a few paces ahead. Frank walked down the center aisle, startling some kneeling worshipers. He didn’t have any clear plan. He was just reacting now; the police were in control of the situation. It was the detectives who went and found the priest—the authorities arranged everything.

“Father,” said the detective sergeant, “this is Frank Tannenbaum. He wants to speak to you.”

“All right, just one moment,” said Frank, asserting some free will. “My name is Tannenbaum, and I’ve led my army here to make one request of you. We want to sleep in the church tonight. Can we do it?”

“No, you cannot.”

St. Alphonsus’ Catholic Church.

“But we’re starving. We’ve come here to spend the night.”

“No, you haven’t.”

“Do you call this living up to the teachings of Jesus Christ?”

“I don’t intend to argue with you on ecclesiastical matters,” snapped the priest. “You’ve got to get out.”

“Well, will you give us money to buy food?”

“No.”

“Will you give us work?”

“No.”

Frank offered his hand. “All right, no hard feelings,” he said. “We’ll go away.” The priest refused to shake, and Tannenbaum walked a few steps, before turning to say again, “All right, no hard feelings, now, remember.”

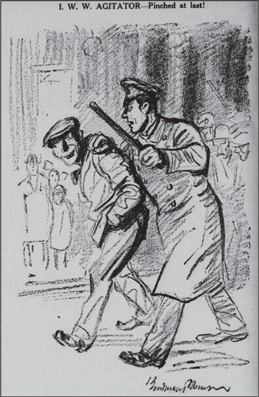

They went back into the main hall of the church, which was now crowded with the unemployed. More protesters were filing in. The policemen by the door let them in gladly—once inside, however, no one was permitted to leave. Frank offered to lead the men back to the street, but the detectives told him to stay put. They were being sealed up, trapped. The intruders and the assistant priests were hollering at each other. The men still outside were shouting. Bells tolled on approaching police wagons. The photographers’ flashbulbs were firing off like ammunition. It was all so ugly and ridiculous that Frank had to laugh. “This is fine,” he said to himself with a wan smile. “This is the best meeting I’ve had yet.” A detective who had disappeared now slipped back inside through the guarded entrance. It was almost a relief when he shouted out, “Frank Tannenbaum! Step forward! You are under arrest for unlawful entry, by order of the commissioner.”

“All right,” Frank said, and submitted to being led out through the doors into the riotous street. Traffic was blocked. Scores of police officers cordoned off the steps, or filtered through the crowds that had spilled from the nearby tenements to watch. He heard them shouting at him—or for him, he couldn’t tell which—as he descended to the street. The detectives lifted him into the green patrol wagon that was backed up to the foot of the stairs, and for a moment he was alone. Then the next prisoners got shoved in with him, and then still more. When the benches were filled, and men were crouching on the floors, the van jolted forward, picking its way through the jammed avenue. At the station house on MacDougal Street, his name was entered in the blotter. For a couple hours they left him waiting in the holding cell while the others were booked, and finally the detectives escorted him uptown to be arraigned.

It was after eleven P.M, when Frank, pale and trembling from exhaustion, was led into a courtroom for the first time in his life. He fidgeted anxiously at the stand, wiping an old kerchief across his face, unconsciously fussing with his wavy hair. Around him, obscure officials spoke in murmurs. “Is that the judge?” he asked the detective, pointing to the court clerk. Then, when the doors opened and the actual magistrate ascended the bench, he was unmistakable—massive and remote, beefy jowls overspreading the high collar of his black robe. He read the charge: inciting to riot, a felony that carried a maximum penalty of five years’ imprisonment.

“Do I have to plead now?” asked Frank. The judge was explaining his options, but he couldn’t follow. Panic rising. He couldn’t answer any of the questions; he didn’t know what to do. It was a relief to hear that the proceeding was rescheduled for the following afternoon, but when the bail was announced—$5,000—the sum hit Frank like a hurled weight, and he staggered and gasped. He looked around for friends. But he was alone. The officers led him out from the courtroom to his cell and locked him away for a sleepless night.

IT WAS A late evening—and a long one—for Police Commissioner McKay as well. That morning, he had issued general orders to his men to keep tabs on Tannenbaum. Then he had spent all day detailing his resources for a comprehensive response. Every conceivable precaution was taken. After dark, he lingered at headquarters, waiting by the telephone. Finally, the call. It was Detective Sergeant Gegan. Tannenbaum was at St. Alphonsus’ on West Broadway. McKay ordered out the reserves, every precinct—Greenwich Street, Elizabeth Street, Mulberry Street, MacDougal Street, Charles Street, Mercer Street, Beach Street—all of them. And then he jogged to his official car and sped to the scene. By the time he arrived, more than seventy-five officers were in action, and the patrol wagons were already being loaded.

One hundred and ninety men and one woman had been arrested, the largest roundup in the city’s history. McKay was in amongst it the entire night: From the church he toured the precinct houses, and then made the late-night trip to the Yorkville court, in midtown, to watch Tannenbaum’s arraignment. It was exhilarating to see his plan coming to a satisfying end. McKay wanted these troublemakers locked away. “Absolutely nothing but a felony goes,” he told a subordinate, “charge every one of them with a felony. We have plenty of room.” Reporters crowded round him, asking when he had started plotting his coup, whether the mayor had ordered him to act. McKay jokingly denied any premeditation. It wasn’t like that at all, he replied, eyes twinkling: “I just happened to be in the neighborhood.”

* * *

ALEXANDER BERKMAN WAS in no mood for anniversaries. And such is life, he marked them everywhere. The March issue of Mother Earth celebrated the eighth year since the journal’s beginning. It was eight years, also, since Johann Most, a onetime mentor in anarchism, had died. And Berkman did not need the Revolutionary Almanac to recall that this was the month that had seen the opening salvos of the Revolution of 1848 in Prussia, or the founding of the Paris Commune a generation later. To spiritually linger in the past was an unpardonable weakness. One should draw lessons from history but live in the present: He despised colleagues who prated forever about their former deeds. But as the commemorations came he could not help recalling the passion of his former self. It was his today, his unbearable today, that made his yesterdays of such concern. If only Berkman could find meaningful work to do—new deeds, new triumphs—then he could release himself at last from this nightmare weight of past generations.

Such despair as he felt was inexcusable. Mere human sentiment was unworthy of the real revolutionist. Detachment in all things was paramount, but he could never quite manage it himself. Not when it came to women. And not when the cause was at stake. Detachment in most things. He was two men. An anarchist philosopher who overflowed with affection for the world, and an anarchist propagandist whose sworn duty it was to inspire rage and goad others to violence. “The propagandist,” he wrote, “must, in a considerable degree, be a fanatic and even hate where the human in him yearns to love. This is perhaps the severest struggle in the inner life of such a one, and his deepest tragedy.”

He had such a desperate need for a worthy crusade—one that could justify his self-imposed misery—that he almost tried to wish it into existence. “In the whole history of this country,” he wrote in the latest Mother Earth, “there has never perhaps been witnessed a popular movement of deeper meaning and more far-reaching potential effect than the raiding of churches by the unemployed of New York.” The out-of-work army had shown the highest qualities of anarchism. It was spontaneous, nonviolent, dignified, and viciously subtle in its revelations of hypocrisy. A few ragged men at a handful of churches had exposed the reformers and reverends, the socialists and police, for what they truly were. And most of all, it perhaps signaled the beginning of the mass movement he so longed for. “The roots of this crusade go deeper,” Berkman wrote, hopefully. “It challenges the justice of the established; it denies the right to starve; it attacks the supremacy of the law; it strikes at the very foundation of THINGS AS THEY ARE.”

The aftermath of Tannenbaum’s arrest, in contrast, was almost too sordid and predictable. The capitalist press, of course, was all relief and approbation. “Stern and repressive measures,” cheered the Herald, “yesterday broke the backbone of the mob of church raiders who had been led through the city for nearly a week by Frank Tannenbaum.” The Socialist newspapers sniveled in their obnoxious way, offering nothing but condescension and hostility to the prisoners. Thus encouraged, the police forbade all further open-air meetings, arresting more speakers in Rutgers Square on the night following the mass arrests. The only one to behave like a man through it all was young Tannenbaum, who refused his friends’ offer to pay his fine, preferring to remain in jail with the rest instead of taking freedom for himself alone.

The city’s newspapers reveled in Tannenbaum’s arrest.

The remainder of the story was just as foreseeable to Berkman, who had witnessed this all unfold before. The claim by officials to have received scrawled death threats, followed by the suspicious discovery of hidden dynamite. The ludicrous spectacle of police incompetence, the stupor of the courts. Revelations of brutality and barbarous conditions—“scenes that would shock the moral sensibilities of man”—inside the city prisons. The betrayal and cowardice of supposed allies in struggle.

No matter. Tannenbaum had revealed a weakness to exploit. And Berkman took it upon himself to do so. He organized a rally at Union Square to show that the spirit of revolution in New York could not be tamped out by a few arrests. On Saturday, March 21, when he arrived, thousands had already gathered. Emma Goldman, back in the city after one of her frequent lecture tours, was first to speak.

“Your toil made the wealth of the nation,” she began. “It belongs to you.” The audience crowded in around her, blocking the northern reaches of the plaza. A bright thin sun did little to warm the freezing air. It was the first day of spring. “The rich are keeping it from you. The officials do nothing to help you.” The thin trees of the park stood lonely amidst the remaining hummocks of snow. It was twenty-five years now since Berkman had first looked out from this vantage. He had spent chilled nights with no other place to shelter. He had fled from charging phalanxes of police. He had paraded here in triumph with his fellow workers. “March down to the mayor. March down to the police. March down to the other city officials.” He had heard Emma make this speech a hundred times. “March upon Fifth Avenue and take that which belongs to you!”

With that, he began to gather the crowds into a loose mass. When they were organized, he strode to the very front. With a pretty young girl on either arm, he led the column up Broadway. He had no permit to parade, but the few detectives assigned to watch the rally followed passively, unable to stop him. Some of the protesters walked in the streets, others claimed the sidewalks, jostling the afternoon shopping crowds in the Ladies’ Mile. Discordant shouting. Snatches of song. At Thirtieth Street, they fell still and silent as a man unfurled a black silk banner. Red letters spelled out one word: DEMOLIZIONE. The column closed in, linking arms. Then, in a shrill, high key, a lone woman began to sing “The Marseillaise.” After a few notes, other female voices joined, and then the men began. In a moment, the revolutionary anthem was on every lip, echoing in half a dozen languages. The sun vanished ominously behind a wall of clouds. And the parade was moving again.

Anarchists on the march.

Fifth Avenue—“Millionaire Avenue”—and here came Berkman with his army. The Waldorf-Astoria, the Metropolitan Club, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Henry Clay Frick’s nearly completed mansion: At each landmark, the demonstrators jeered, chanting, “Down with the parasites! Down with the parasites!” Anarchists took command of every major intersection, halting trolleys, blocking traffic. One rioter, a young woman, rapped on automobile windows, forced open the doors, and spat at the passengers. It was a rout. A revolution. There were no uniformed police on hand at all, just the few detectives, who found themselves helpless to intercede. “Berkman and his followers,” a reporter wrote, “were laws unto themselves.”

When the parade finally ended with a celebratory dinner at the Franciso Ferrer Center on 107th Street, Berkman felt once more the young man’s thrill in combat, “the spirit of revolt that has fired the hearts of the downtrodden in every popular uprising.” He judged the city’s mood and believed he had thousands with him. From his enemies, he saw only cowardice and panic. “What! The starvelings to be permitted to parade their naked misery, to threaten the moneychangers in their very temple?” he pantomimed disdainfully. “The black flag of hunger and destruction to wave so menacingly in the wealthiest and most exclusive section of the metropolis, the fearful cry of Revolution to thunder before the very doors of the mighty! That is too much!”

JUST ONCE, John Purroy Mitchel wished the citizenry might remain sensible instead of indulging in hysteria at the slightest indication of unrest. But so far during his short time in office, his constituents had shown no inclination to do so. The mayor had been motoring uptown on Fifth Avenue at the time of the anarchist “revolution.” He had seen a clump of people on the march, and the sight had been so innocuous that he had driven on without giving it the slightest attention. When newsmen interrogated him outside of his office, he treated the affair as a joke.

“Some of the speakers urged that they should call on you here at the City Hall and demand their share of the world’s riches,” a reporter asked. “What would you do in a case like that?”

“I would suggest that instead of calling they file their application for the riches.”

“I suppose you know that Emma Goldman denounced you in true anarchistic style at the meeting.”

“That is habitual and chronic,” said Mitchel, “and she would denounce anybody who happened to be in office.”

But many of his supporters took the threat more seriously. “It will not be easy for the police to explain their toleration of the disorderly demonstration,” complained the World. “The procession was worse than disorderly. It was lawless.” Once again, just as with the church invasions, he was being pressed to respond with drastic measures. “This is an attack—an attack on the social system,” declared the Times. “Its aim is nothing less than revolution.” The detectives on the scene could not restrain their frustration. “It is evident that the men downtown do not recognize the seriousness of this movement,” said Detective Gegan, who had arrested Tannenbaum. “We who follow them from day to day see that they are gaining strength, and unless they are checked serious consequences may result.” Panicky rumors were abroad. The word that anarchists had occupied Fifth Avenue had been wired to ships at sea, and some papers were reporting that Mitchel had called on the National Guard to restore order. Finally, the mayor snapped at all the hectoring. “That is all damned nonsense,” he said. “The more attention there is paid to such insane stories the more the agitators are helped.”

Nonetheless, certain interests had to be placated. On the Monday after the Fifth Avenue debacle, Mitchel again met with Commissioner McKay. And again they emerged from their conference with strong statements. Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman were well-known to them; the citizenry could rest easy, knowing that all prominent anarchists in the city were under constant surveillance. “They may have their public meetings,” the mayor decreed, “and their speeches may have the widest latitude, but any general disorder or disturbance of the peace will not be permitted.”

* * *

ON THE MORNING of March 24, guards scraped open the iron gate of cell number 813 of the Tombs prison, and Frank Tannenbaum was marched to a lavatory, where he freshened up for trial. Around ten A.M., when the heavy wooden doors of the General Sessions Court opened for him, the benches had already filled. There weren’t as many friends as he had hoped for, but he showed nothing but composure, nodding to the few comrades he did recognize and taking his seat at the bench.

The attorneys spent hours wrangling over prospective jurors, most of whom freely admitted their biases against him. But they hardly needed to say so. Their smug, well-fed appearances told the same, as did their occupations: real estate, architecture, management, foreman, speculator. These men were not of his class. They would not sympathize with what he had done. He had never wanted to submit to this trial, but his friends had insisted he go through with it and he had finally agreed. Not that he had hope of an acquittal; maybe the publicity would make good propaganda.

On the afternoon of the first day, and all through the second, the state presented its case. The police detectives perjured themselves shamelessly, claiming Frank had entered St. Alphonsus’ Church despite their protests, when in fact they had invited him inside—and that he had refused to leave, when, to the contrary, they had barred his exit. The prosecutor called his men “a mob,” and the judge overruled his attorney’s objections. The defense called as witnesses the newspaper reporters and photographers who had witnessed the arrests. All of them corroborated his story. The unemployed were not violent, no property had been damaged, the police had manufactured the entire episode. By the time the jurors withdrew on the evening of the trial’s third day, the truth of the case had been so clearly established that his friends assured him justice would prevail.

Forty-five minutes later, the twelve representatives of bourgeois order returned to pronounce their verdict: guilty, of course. The judge lectured him about American democracy and gaveled him the maximum sentence, a year in the workhouse on Blackwell’s Island.

Frank Tannenbaum smiled.

“I would like to make a statement, I think,” he said.

“You are,” said the judge, “at liberty to make any statement you desire.”

Frank told about the men he had met in the Tombs, and how they were as decent as any magistrate or district attorney. He described the rapture he had felt watching his hungry men eat, and how if that feeling wasn’t religion, then nothing was. He insisted that he had been polite from first to last. He recalled the first time he had gone into a courtroom and hadn’t been able to tell a clerk from a judge, and how now—after nearly a month’s experience with the legal system—he knew all he needed to know: that the working class could expect no mercy from the law. When the first man had been convicted in the first court, he said, justice had flown out the window and never returned.

“I suppose,” said Frank Tannenbaum, “that the press tomorrow will say I wanted to make myself out a hero or a martyr. I don’t know who it was who said, some well-known preacher, that society would forgive a man for murder, theft, rape, or almost any crime, except that of preaching a new gospel. That is my crime.”