At one thirty in the afternoon on the fourth of April, crowds enjoying the Saturday half-holiday in Union Square were startled at a sudden incursion by a massive contingent of police. Four hundred officers hurriedly deployed, asserting control over the area. Some patrolled the outer boundaries. Others swept up and down along the pathways of the park, warning idlers to “move on.” Fifty uniformed men filed into hiding within a pavilion at the north end of the plaza; scores more concealed themselves inside a construction shed, and another hundred or so plainclothesmen mingled among the spectators.

Commissioner McKay arrived in his green automobile and established a command post on Seventeenth Street, between Broadway and Fourth Avenue. During the previous two weeks he had endured ceaseless criticism for having failed to prevent the anarchists’ last parade through the wealthiest neighborhood in Manhattan. This morning, he had received word that they were planning to repeat the performance, and he was absolutely determined to forestall them. To do so, he called on all the department’s resources. Besides the men on the scene, he had two hundred more officers dispersed among the basements of every fashionable club and hotel from the Ladies’ Mile to Harlem. One thousand more reserves stood ready in the precincts to act as reinforcements. A general order issued to all these forces that morning was terse and direct: “Break ’em up!”

There were two rallies planned for the afternoon. The Central Federated Union, a conglomeration of A.F. of L. locals, had received official approval from the city to hold their meeting. The anarchists, as usual, had not deigned to beg for “the kind permission of the master class and its armed hirelings.” Berkman suspected that the police were intentionally pitting the groups against each other, using the moderate trade unionists to discredit the radical unemployed. Newspapers, he knew, would gleefully exaggerate any conflict between rival labor factions. So he had two choices. He could march and face accusations of fomenting dissension within the working class, or he could postpone his parade.

It was after two P.M., and no one outside Berkman’s inner circle yet knew what he had decided. Six or seven thousand demonstrators were milling around at the northern edge of Union Square, where the trade-union meeting was just being called to order. Spectators hovered on the periphery or watched from windows, hoping to see some excitement. Three motion-picture cameras swept the scene. McKay and his inspectors surveyed the crowd, while reporters and photographers scrambled to cover any potential outbreak. Lincoln Steffens stood on tiptoe trying to get an adequate view. Everyone kept sharp for the anarchists.

And then with shout and shove, they were there. The group surged forward in a tight, organized mass, “seeming to spring from the ground,” wrote a reporter, “so rapid was their approach.” The militants pushed through the crowd, distributing propaganda as they forced a path toward the speaker’s platform. The mob tightened in, cheering crazily. At the front, Berkman scaled a stacked tower of lumber that served as an improvised stage. As the highest spot in the area, the platform also happened to be the police operations center, so as he turned to address the demonstrators he was just a few feet from McKay and his inspectors. Everyone craned closer to hear.

He started with his usual imprecations against labor fakirs and the “capitalist class.” Then came the substance of his address. “We will postpone our meeting,” he said, “because we want the people of New York and of the country to see our solidarity with labor, whether organized or unorganized.” As Berkman clambered down to the sidewalk, the police inspectors momentarily relaxed.

At the very moment their attention lapsed, they lost control of the situation. A different group of radicals—either unaware that their rally had been put off, or unwilling to abide by the decision—chose this instant to raise signs reading HUNGER, UNEMPLOYED UNION LOCAL NO. 1, and TANNENBAUM MUST BE FREED. Seeing the placards, policemen at the boundaries of the demonstration thought a parade was forming and recalled their orders to “Break ’em up.” Forming wedges, they sliced into the throng. Commanders signaled frantically, but whether to stop the assault or urge it on, it was impossible to know. “The crowd jeered and yelled and the banners continued to wave for a moment or two,” a reporter wrote. “Then the flags were jerked from the hands of the color bearers, and a minute later those color bearers … were on their way to the East Twenty-second Street Police Station.”

Riotous demonstrators trailed the officers and their prisoners to the upper edge of the park, shouting threats and turning back only when a line of mounted policemen cantered over to block their path. Facing south, the leaders improvised a new plan. “Come on, men,” shouted an unemployed anarchist named Joe O’Carroll, “We’ll march to Rutgers Square.” With him in the lead was Becky Edelsohn, “a comely young woman” of “electric vitality” in her mid-twenties, who was a former lover of Berkman’s and was becoming a leading campaigner for militancy. During the previous parade up Fifth Avenue, she had been the one who shocked even some of her own cohort by prying open the door to a limousine to spit at the faces of the women inside.

Arm in arm they showed the way, and within a minute, hundreds had fallen into line behind them. The column soon stretched the entire length of the park. Demonstrators shouted “Kill the capitalists!” and “Revenge Tannenbaum!” Detectives scurried to head off the leaders, while the mounted patrol trotted menacingly on the parade’s flank and the hidden officers streamed out from their concealed positions. For a few moments, the two sides marked each other. Then, at Fourteenth Street, the detectives ordered the protesters to disband. The crowd responded with taunts and hisses. And, at last, detectives Gegan and Gildea—the officers who had been pining for this moment since early March—ordered the attack.

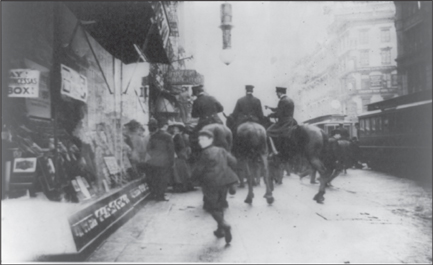

The horsemen formed a column, drew their batons, and spurred directly toward the middle of the parade. “Invective and imprecations hurled at the policemen changed to yells of alarm and terror” as the surging cavalry struck the mass of demonstrators. Protesters fled, if they could, or were ridden down. Horses wheeled and charged, wheeled and charged, knocking dozens to the sidewalks, raising a clamor that could be heard for blocks around. At the front of the march, plainclothesmen and uniformed policemen pushed their way toward the heart of the mob. “The officers fought coldly, contemptuously, systematically, shoulder to shoulder and elbow to elbow,” a reporter wrote. “The I.W.W. and anarchists battled wildly and lost all judgment in a furious rage.” Each side unleashed its resentment and hatred on the other. “The yells of defiance, the curses, the screams of pain from men and women, the clacking of galloping horses, the curt orders from police commanders made a chorus which overwhelmed the ordinary song of the streets.”

Mounted officers disperse the anarchists.

In the first moments of fighting, detectives had grabbed O’Carroll and dragged him, struggling, from the melee. His friends chased behind, cuffing and shouting at the arresting officers, pulling their hair in a wild attempt to pry him free. The panicked and outnumbered cops lashed out indiscriminately, beating the thin, sickly O’Carroll on the head until a deep gash opened across his scalp and blood was pouring over his face and soaking his clothes. Becky threw her body over his, shielding him as best she could from the policemen’s blows and shouting desperately, “Save Joe from the oppressors of the poor!”

Hearing her calls for help, an unemployed radical named Arthur Caron moved to intervene. Within seconds, he too was on the ground, being struck again and again with blackjacks and fists on his head and legs. “For Christ’s sake,” he pleaded, “stop hitting me.” They grabbed him up, manhandled him toward a patrol wagon, and threw him into the hold. O’Carroll was already in the back, two officers rode up in the cab, and several plainclothesmen stood out on the running board. The door slammed shut as the vehicle coughed into motion. A cop hissed at Caron, “You bastard, we’ve got you now,” and punched him in the face. He tried to get up, blood racing from his nose. “You bastard, lie still!” they yelled, as they all beat him on the back of his skull. O’Carroll staggered over and cradled Caron’s wounded head. “Poor boy!” he muttered in shock. “Jesus! You’re getting it awful.”

At the East Twenty-second Street station, the two crushed protesters were dragged from the wagon and shoved down onto opposite ends of a long bench. Before they could be booked, the detectives made them wash the blood off their faces, necks, and hands to make them presentable to the magistrate. Then they had to think of what charges they would file against their prisoners.

“That’s O’Carroll,” one of them said. “We’ll charge him with striking an officer and resisting arrest.”

“What’ll we charge that big bastard with?” asked another, gesturing to Caron.

“Charge the fuck with trying to take him away from the police and yelling, ‘Kill the bastards!’“

“NO SCENE IN New York for years has approached the violence of the outbreak in Union Square yesterday,” proclaimed the next morning’s Sun. There had been eight arrests and dozens of injuries. For more than a week, newspaper editors had been calling for stern measures against protest demonstrations, and for now the press seemed satisfied with the result. “The police,” a Times reporter wrote, “led by a detachment of mounted men, wielded their clubs right and left, and left many aching heads in their wake.” The World expressed similar contentment at seeing “a couple of hundred vile-tongued I.W.W.’s … routed by unmerciful clubbing.” After the battle, Commissioner McKay surveyed the scene of his masterstroke with complacency. “Though what did happen was bad enough,” he told reporters, “anything might have happened, and we were prepared for it.” Surely, no one would now accuse him of overindulging these anarchists.

* * *

THE TONE OF the telegram from Washington hinted at what was to come:

COMMITTEE ON MINES AND MINING DESIRES YOUR TESTIMONY ON COLORADO STRIKE WILL YOU APPEAR IN WASHINGTON WITH BOOKS PAPERS AND LETTERS WITHOUT FORMAL SERVICE AND WHEN ANSWER.

This seemed brusque even for a cable message, but John D. Rockefeller, Jr., refused to be baited. YOUR COURTEOUS TELEGRAM OF MARCH 31ST I FIND UPON MY RETURN TO THE OFFICE THIS MORNING, he replied. IF IT SUITS YOUR CONVENIENCE I WILL BE GLAD TO APPEAR BEFORE YOUR COMMITTEE ON MONDAY MORNING, APRIL 6TH, AT ANY TIME AFTER NINE O’CLOCK.

He was not sure why the investigators wanted to see him in particular. After all, he was merely one of several directors who sat on a board of one of many companies involved in a nearly statewide coal-mining strike. There must have been dozens of business leaders with more knowledge of the situation. Though it was true that he exchanged weekly—and at times daily—correspondence with his executives at the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, he himself had not even visited the state in a decade. “What possible value any knowledge which I may be able to impart may be to this inquiry, I do not know,” he wrote to his father. “However, since the invitation has been extended, I felt it wise to accept it without hesitation.”

The five congressmen on the subcommittee had just returned from Denver themselves. During their three-week visit to Colorado, they had conducted hearings throughout the troubled districts, interviewing company bosses and union leaders as well as dozens of individual miners and other locals. Through these meetings they had uncovered a “system of feudalism” reinforced through violence, corruption, and coercion. The state militia was controlled by the mine operators, while the strikers in their tent encampments were armed and organized as well. Every hand gripped a shotgun or rifle, and twenty-two people had by now been killed.

The committee members had found no blameless parties, but they had been particularly irritated by the stubbornness of the corporate executives—men like L. M. Bowers, the Rockefeller-appointed chief at Colorado Fuel & Iron. He had reiterated for them his belief that the company treated its workers as well as they had any right to expect. “The word ‘satisfaction,’” he wrote to Junior, “could have been put over the entrance to every one of our mines.” If it wasn’t for the interference of agitators, the miners would be calm as cattle. The only thing worse than a union organizer, in his mind, was the “goody, goody, milk and water” brand of reformer. “It will be a happy day for the business man,” Bowers had written in 1912, “when a lot of these social fanatics are placed in lunatic asylums, and the muckrakers, labor agitators and the grafters are put in jail.”

The congressmen saw that this intransigence was hindering any chance of industrial peace in Colorado. “Society in general cannot tolerate such conduct on either side,” they decreed. “The statement that a man or company of men who put their money in a business have a right to operate it as they see fit, without regard to the public interest, belongs to days long since passed away.”

Thus the antagonism that Junior had detected in the telegram, and which manifested itself as soon as he arrived in the Washington, D.C., hearing room, was not entirely unexpected. Still, he indicated no apprehensiveness as he settled in at the witness table with his lawyer and a sheath of documents. At ten A.M., on April 6, the chairman—Martin D. Foster, a Democrat from Illinois—initiated the proceedings.

THE CHAIRMAN. You may give your name and residence to the stenographer, Mr. Rockefeller.

MR. ROCKEFELLER. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., 10 West Fifty-fourth Street, New York.

And that was just about the last collegial exchange of the day.

From then on, Junior was peppered with hostile questions, mockery, and hectoring. The congressmen repeatedly interrupted and challenged him on every last little detail of fact. He had wondered what he—who’d had so little direct contact with the strike situation—could add to the investigation. Now it was clear that the interrogators had no interest in his expertise; they intended to showcase his ignorance.

THE CHAIRMAN. You know when the strike started, do you?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. I could refer to the exact date in this correspondence. It was in September or October, some place along there: but the date I would not have retained.

MR. BYRNES. We can all tell you it was the 23d of September.

MR. ROCKEFELLER. Well, you see, you have been there.

THE CHAIRMAN. Do you realize that since last September this strike has been reported in the press throughout the country, that the governor of Colorado has called out the militia to police the disturbed district, and that the conditions prevailing in that district were shocking, according to such reports, and that the House of Representatives deemed it a duty to undertake this investigation?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. I have been fully aware of all those facts.

THE CHAIRMAN. And yet you, personally, nor the board of directors, have not looked into the matter?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. I can not say as to whether the board of directors has—

THE CHAIRMAN (interposing). Whether conditions were correct as reported in the press?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. I can not say as to whether the board of directors have looked into the matter or not, their meetings being held in the West.

THE CHAIRMAN. What action has been taken personally to find out about the trouble in Colorado?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. This correspondence will give the whole thing.

THE CHAIRMAN. Personally, what have you done, outside of this, as a director?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. I have done nothing outside of this; that is the way in which we conduct the business …

THE CHAIRMAN. You do not consider yourself a “dummy” director in the Colorado Fuel & Iron Co.?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. I do not.

This was how all the family’s operations worked, as Rockefeller patiently explained. Trusted operatives handled daily affairs, with only minimal interference from 26 Broadway. Senior had run Standard Oil that way, and it was hard to cavil with its effectiveness. New York received intelligence from the local proxy—in this case, L. M. Bowers. If he reported that the miners were treated leniently, and had been bullied and preyed upon by alien agitators into striking—that, as one of his associates had claimed, “the strike of our coal miners was literally forced upon them against their wishes by people from the outside”—then that information was considered reliable.

THE CHAIRMAN. What, in your judgment, should be the relation between employee and employer?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. That is a pretty big and broad question, is it not?

THE CHAIRMAN…. Yes; I am getting your opinion, because you have had a good deal to do with the civic uplift of the country, and you ought to have a good idea and an intelligent opinion of those matters. I think it would be valuable to have it in the record.

MR. ROCKEFELLER. If you can make the question at all concrete, I should be glad to try to answer it.

THE CHAIRMAN. You know there has been growing in the country a belief that there does not exist between employers and employees the relation that there should be between the two. What do you say as to that?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. I believe that the employer and the employee are fellow men, and I see no reason why they should not each treat other as a fellow man. You are asking a broad question, and I am giving a pretty broad basic reply. It is difficult to get closer to the subject.

THE CHAIRMAN. That leads me to ask this question: As a director of the Colorado Iron & Fuel Co., and representing a large interest in that company, have you personally taken the trouble to know any of those miners or to look into their conditions there, their manner of living, and all that?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. Oh, when I was investigating vice in New York I never talked with a single prostitute. That is not the way I have been trained to investigate. I could not talk with 10,000 miners.

THE CHAIRMAN. No; you could not.

For hours he parried these attacks with a civility that soon attracted the sympathy of the reporters who witnessed his performance. “Never ruffled,” they wrote, “polite and thoroughly suave,” he was “at ease throughout.” Few public men had so much experience in facing derision. Junior’s position as his father’s son had meant he’d been perpetually underestimated his entire adult life. This session ranked as a minor irritation compared to some of the barbs he’d already endured. He did not stammer. He did not dodge or sidestep. Instead, he waited to make his own case against organized labor. And, finally, he did.

THE CHAIRMAN. But the killing of these people, the shooting of children, and all that that has been going on there for months has not been of enough importance to you for you to communicate with the other directors, and see if something might not be done to end that sort of thing?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. We believe that the issue is not a local one in Colorado; it is a national issue, whether workers shall be allowed to work under such conditions as they may choose. And as part owners of the property, our interest in the laboring men in this country is so immense, so deep, so profound that we stand ready to lose every cent we put in that company rather than see the men we have employed thrown out of work and have imposed upon them conditions which are not of their seeking and which neither they nor we can see are in our interest.

THE CHAIRMAN. And you are willing to go on and let these killings take place—men losing their lives on either side, the expenditure of large sums of money, and all this disturbance of labor—rather than to go out there and see if you might do something to settle those conditions?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. There is just one thing, Mr. Chairman, so far as I understand it, which can be done, as things are at present, to settle this strike, and that is to unionize the camps; and our interest in labor is so profound and we believe so sincerely that that interest demands that the camps shall be open camps, that we expect to stand by the officers at any cost. It is not an accident that this is our position.

THE CHAIRMAN. And you will do that if it costs all your property and kills all your employees?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. It is a great principle.

THE CHAIRMAN. And you would do that rather than recognize the right of men to collective bargaining? Is that what I understand?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. No, sir. Rather than allow outside people to come in and interfere with employees who are thoroughly satisfied with their labor conditions—it was upon a similar principle that the War of the Revolution was carried on. It is a great national issue of the most vital kind.

The hearing was adjourned at 2:25 P.M If Junior was concerned about his performance, he was reassured the next morning by the newspaper headlines. For the first time in his life, the press treated his words seriously, taking note—with a certain surprise—of his gravity and poise. And then the congratulations began to arrive. “Nothing I have read or heard in recent years,” wrote Charles M. Schwab, “so fully and clearly and logically expresses the views that I hold with reference to a situation of this kind, as the testimony you have given.” J. P. Morgan, Jr., sent a letter saying, “It was exceedingly amusing to see the common-sense business point of view as opposed to the political and excited sociological point of view which all members of Congress appear to occupy.”

The most welcome notes came from his parents in Tarrytown. “It was a bugle note that was struck for principle yesterday before our country,” wrote his mother. His father bragged to a friend, “He expressed the views which I entertain, and which have been drilled into him from his earliest childhood.” To show his gratification, Senior presented his son with a generous gift: ten thousand shares of Colorado Fuel & Iron Company stock. “Nothing could give me greater satisfaction,” Junior replied to his mother, “than to feel that you and Father are satisfied with my effort of yesterday.”

But in fact his conscience was disturbed. One exchange, in particular, had touched on his most delicate feelings.

THE CHAIRMAN. Do you think that a director like you are of a company such as the Colorado Fuel & Iron Co. should take the responsibility for the conduct of the company?

MR. ROCKEFELLER. Mr. Chairman, in these days, where interests are so diversified and numerous, of course, it would be impossible for any man to be personally responsible for all of the management of the various concerns in which he might be a larger or smaller stockholder … I do not know of any other way in which a company can be run except by putting the responsibility upon the officers, and then holding them to it, and seeing that they perform in a proper way the tasks imposed upon them.

Junior was profoundly aware that modern industrial organization was incompatible with individual responsibility. This was the very realization that had prompted him to retire from business four years earlier. Colorado Fuel & Iron was the one directorship he had retained, and he had done so only out of a feeling of duty to his father. Now he was in the exact predicament he had hoped to avoid, publicly vouching for the choices of others—men he trusted, but whose actions he could not control.

The congressmen had nudged him toward uncertainty. Perhaps he had delegated too much responsibility. From L. M. Bowers he had received a vehement, almost feverish, letter of congratulations. It worried him. Hearing that Bowers happened to be visiting his home in upstate New York, Junior sent him an urgent cable: THINK IT IMPORTANT TO SEE YOU BEFORE YOU GO WEST. If they could meet personally, maybe he could convince his subordinate to offer some concessions, or at least assure himself that the man was still qualified to lead.

But the telegram arrived too late. Bowers had already entrained for Colorado.

* * *

THE POLICEMEN’S TESTIMONY was disjointed and contradictory. Their assailants came from uptown; no, from the downtown side; they had yelled “Kill the Cops!” and some other such unlikely things, and had initiated all the fighting. The presiding magistrate shook his head throughout, with a baleful smile.

And then Arthur Caron took the stand: his eye swollen shut, his face checkered with bruises. “The next thing I knew I got a blow over the back of the head with a blackjack,” he said. “I tried to straighten my hat, which was knocked off, and I received a blow over the wrist. A blow was struck into my kidneys at the same moment. I dropped to the sidewalk, but I tried to get up, and then I was shoved into an automobile. Policeman Dawson jumped on the running board and hit me twice in the face, while somebody else hit me on the back.” After he had finished, the magistrate acquitted Caron of all charges, and urged his defense attorney to launch an investigation of the police department. “The condition of these prisoners,” the judge admonished the officers, “is enough to make us feel ashamed.”

On April 8, when Arthur Caron walked out of the courtroom at 300 Mulberry Street, his derby was battered through in three places. But he was a free man.

COMMISSIONER MCKAY HAD helplessly watched the burnish fade from his coup. The same public that had chided him for inaction now complained of his exuberance. The Tribune demanded an official inquiry into the violence at Union Square. “Disapproval of the methods and purposes of the Industrial Workers of the World,” wrote an editor at Outlook, “so far from affording an excuse for brutal police conduct, should make the police authorities the more scrupulous in seeing that the rights of such people are maintained.” The Times alone continued to support the commissioner and his men. “It is nonsense to say that the police made too free use of their heavy clubs,” the paper insisted. After all, “none of the malcontents was disabled.”

Mitchel had spent the weekend in Atlantic City, but he sent an emissary to witness the trial where Caron was vindicated, lending “weight to rumors that I.W.W. sympathizers had gained the Mayor’s attention.” On his return he attempted to restore composure to the metropolis, claiming for the second time in a month that there was “no such thing as an ‘I.W.W. situation’” and reiterating his commitment to principled government. “I want the police to take all necessary steps to prevent breaches of the peace and law,” he said. “On the other hand … there must be no unnecessary clubbing.”

These speeches were eagerly accepted as a sign of coming peace. But it was Mitchel’s second act that really indicated his attitude. He fired the police commissioner.

The mayor had always intended to replace McKay, who was hired by the preceding administration and had never matched the profile of a Mitchel appointee. He made no claims to social-scientific expertise, had not published any studies, nor conducted sensational experiments. If he had shown a knack for leadership, perhaps he could have remained longer, but the only flair he had revealed was for mismanagement. On April 1, he received a letter from the mayor that acknowledged his “efficient and faithful” service—and that also accepted his resignation. The debate over his replacement, which had begun even before Mitchel’s Fusion government had taken office, now intensified into a public canvass of suitable candidates for what was widely considered to be “the hardest job in the entire city government.”

Some of the most prominent administrators in the nation saw their names mentioned in connection to the post. G.W. Goethals, engineer of the Panama Canal, William J. Flynn, head of the U.S. Secret Service, and General Leonard Wood, the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, were all courted in turn. And each eagerly declined to serve. “The surest way to be out of a job within a year,” people said, “was to become Police Commissioner of New York.” Fifteen men had already come and gone in the sixteen years since the position was created—“Commissioner had succeeded Commissioner at the same reckless pace”—and if not all had been downright crooked, neither had they especially distinguished themselves. “Few have had time to learn more than routine,” an editor wrote, and “none has stayed long enough to impress upon the department a continuous and consistent policy.” Of all the men to lead the police force, only one had not been ruined by it—Theodore Roosevelt—and he had served from 1895 to 1897, before the consolidation of the five boroughs into Greater New York.

Ask most New Yorkers to define police, and the response, according to the Outlook, would go like this:

police (noun)—a blackhander to whom the use of bombs is forbidden, but otherwise fully authorized by the state. (v. t)—to beat, club, shoot, bulldoze, threaten, or graft. (F. < L. politia, state; < Gr. politeia, city.)

Of the city’s many failures of governance, none had caused more chagrin than its “corrupt and disorganized Police Department.” The cops were considered to be “the dirtiest, crookedest, ugliest lot … outside of Turkey or Japan.” Outrages from the force had been so common during the previous twenty years that by the 1910s they elicited little more than a shrug. “Once more New York City has set the Nation by nose and ears with a scandal of police corruption,” sighed a longtime critic of the department, with absolutely no surprise.

In a typical year, New Yorkers committed six times as many murders as the residents of London, and could almost match the combined homicide totals for all of England and Wales. Prisoners waited months to be tried, and conviction rates were appallingly low. The civil service procedure was faulty, and politicians played favorites anyhow; promotion was haphazard and often found the wrong man. No one thought to maintain adequate files; “our criminal statistics are so crude and incomplete,” complained the Bureau of Social Hygiene, “that deductions are difficult to make and when made are little better than rough estimates.” Every sort of depravity was sanctioned by grafting cops, and “collusion between exploiters of vice and officials in the Police Department” was common knowledge.

Every decade or so an investigation would reveal the dirty details of these operations—the Lexow Committee in 1894 and 1895, the Mazet Committee in 1899—but they had no discernible effect. The public had more or less given up on reform; it would have been satisfied if law-enforcement officers would just conduct their crooked business out of sight. Lincoln Steffens described New York–style Good Government as “clean streets, and well lighted; an orderly police department, with well-ordered blackmail and corruption (of which people don’t hear), and general comfort and cleanliness.” But even that was too much to ask.

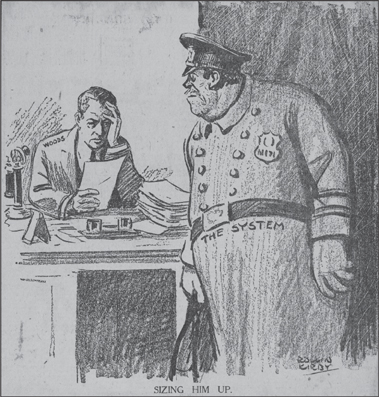

There were irregular, spectacular occasions of depravity, and these could still raise a newspaper reader’s eyebrows. But far more detrimental to morale and efficiency was the quotidian influence of habit, suspicion, silence, and self-interest that was universally known as the System. “The police ‘system’ in New York, as the man-on-the-street understands it,” explained a muckraking reporter, “consists of a cohesive group of men who sell the privilege of breaking the laws, surrounded by a larger group which, while honest, is stultified by the tainted spirit of the powerful and corrupt few.” Take care to sustain the System, and it would take care of you. Every few years a commissioner might pass through with some improvements in mind, but the policemen knew enough not to worry. The reformer would be gone and the System would remain.

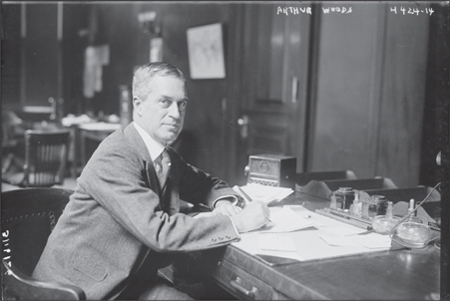

“I believe it is essential that the police commissioner should have a long term of office,” a progressive activist had told a conference in 1913. “Today he is a bird of passage. And usually he flies so fast that the men on the force have hardly time to determine his species. The policy of the force, when a new commissioner is given them, is to try to size him up—what kind of man he is—and then to humor him as the occasion calls for.” The speaker’s name was Arthur Woods, and on April 8, the same morning that the I.W.W. agitators were being acquitted in the Magistrate’s Court, Mayor Mitchel swore him in as the tenth police commissioner in the history of Greater New York.

Waving off his chauffeured car, Woods walked up from City Hall to police headquarters at 240 Centre Street, arriving a few minutes before noon. As cameramen snapped photos for the next day’s papers, he chatted with the outgoing chief. Best wishes were exchanged; the “room filled rapidly and every one was as happy as if the occasion were a picnic.” At precisely twelve o’clock, Woods sat at his desk for the first time and signed general order No. 15, finalizing his “assumption of the government and control of the Police Department” and placing its nearly eleven thousand men under his authority. “Is there anything I can do for you?” McKay asked, preparing to leave.

Arthur Woods.

“I wish you’d pray for me,” Woods replied.

“I HAVE DONE a good many things,” Arthur Woods once said of himself. “I have been a newspaper man, and I have been a schoolmaster, and I have been a business man. It is pretty hard to generalize from all those three.”

He was the great-grandson of the founder of Andover Theological Seminary, the grandson of a president of Bowdoin College; his father had earned a fortune in textiles. After graduating Harvard in 1892, he spent a year at the University of Berlin, and then returned to teach English literature at Groton, where Franklin Delano Roosevelt numbered among his students. When the classroom became too confining, he contemplated a missionary’s life in the Philippines but instead asked his friend Jacob Riis for a position on the Evening Sun. As a police reporter, he covered grafting officials, the Black Hand, pickpockets, and safe breakers—taking lessons from the Other Half that he could never have acquired as a prep-school don.

Eager to apply this experience to a useful cause, he agitated for municipal reform. In 1907, the city created a new position for him—the Fourth Deputy Police Commissionership, with jurisdiction over the Detective Bureau—so that it could benefit from his expertise. He accepted, deferring the appointment to steam to England at his own expense to study the methods of Scotland Yard. For two years he pushed innovations, reorganizing the undercover branch and introducing the use of police dogs. But when the commissioner he served under was replaced by a Tammany functionary, he returned to private life. In 1913, the potential of a Fusion victory brought him back to politics. Becoming a top strategist for Mitchel’s campaign, he served for a few months as the mayor’s official secretary. When everyone else turned down the thankless position of police commissioner, Arthur Woods jumped at the job that nobody wanted.

He was forty-four years old in 1914, tall, with graying hair and strong features that were just starting to sag. To one reporter he seemed “a keen, dark, alert, well-groomed gentleman—very much the gentleman.” Photos made him look severe, but acquaintances described his “crust of levity” and a “light and airy way of talking.” He lived at the Harvard Club in midtown with other wealthy bachelors, and his peers judged him an awfully good fellow. “Just as he was in school, so he is to-day,” a member said. “Whenever a man’s in trouble and needs a confidant, he goes instinctively to Woods.” Since his college days, he had been “engrossed,” even “obsessed” with theories for “municipal progress and social betterment.” Having mastered the literature of reform, he understood the connections between crime and housing conditions, employment opportunities, or social neglect. “Arthur Woods had ideas of his own,” Edward Mott Woolley would write in a profile for McClure’s. “The traditional scheme of a police department is to delve out crime and abet the punishment. Commissioner Woods saw an additional function in the department: the prevention of crime through the removal of the impulse of people to commit it. He believes that crime is due largely to environment.”

“There has never been a Police Commissioner quite like him,” gushed a reporter for the Times. “He may not succeed in carrying out his ideas, but he can never be charged with a lack of them, or an unwillingness to fight for them.” In Arthur Woods, New Yorkers believed they had found the leader to transform their police department into an efficient, twentieth-century force. “Few men,” proclaimed Outlook, “have come to municipal office more fitly trained for its duties than he.”

Commentators wondered if the new commissioner could make any headway against the “System.”

On the evening of his first day in command, Woods ate dinner with Chief Inspector Max Schmittberger, the highest-ranking uniformed officer on the force. Afterward, taking a police automobile, they toured several uptown station houses. At each precinct he made “quick upstairs, downstairs, into-the-cellar explorations,” examining cells and blotters, explaining to the anxious men on duty that he was “just getting acquainted.”

Down on East Fourth Street, meanwhile, five hundred angry, excited radicals—as well as an undetermined number of plainclothes police—were crammed into the Manhattan Lyceum to discuss the next phase of the anarchists’ campaign against the city. O’Carroll and Caron sat onstage, where their wounds could be most effectively displayed. Becky Edelsohn spoke first, arguing that it was the newspaper editors and the Rockefellers who were the real inciters to riot. “It is difficult for me to speak in moderation of these cowardly police,” she went on, “who for a few measly dollars … beat and almost kill the working classes.” Berkman, who had disappeared just at the moment when the previous Saturday’s violence was commencing, spoke with even more fury. “If I had seen the brutality of the police,” he sputtered, “if I had seen it with my own eyes right on the very spot, and if I had had a revolver, I would have used it.” Rage sent his rhetoric right over the threshold of decency. His bloodcurdling climax was all but unprintable. The morning papers transcribed it as “To_____with all the____ ____ ____!”

Berkman ended with a promise to return to Union Square on Saturday, April 11, for a “monster mass meeting” to assert the right of free speech. “I believe in resistance!” he shouted. “I claim the right to preach riot if I want to!” And in three days’ time, he intended to see if anyone—including the new police commissioner—would attempt to stop him.

ARTHUR WOODS KNEW the potential gravity of Berkman’s threat as well as any officer in the department; he was familiar with the anarchist’s methods and considered him an “auld acquaintance.” The two had first confronted one another six years earlier, in 1908, during a similarly miserable winter when mass joblessness had again posed a desperate crisis.

In late March of that year, thousands of unemployed protesters had crammed into Union Square for a socialist rally. Within minutes, the police had arrived to break up the demonstration. Inevitably, resistance led to clubbing and scuffles. At the height of the violence, Woods, in his role as fourth deputy commissioner, had arrived with a detachment of reinforcements. With his help, the officers cleared the square and the danger appeared to have subsided. Only a few reporters and some stragglers remained. A contingent of twenty cops lined up. Their work done, they formed ranks prior to being dismissed.

As the men stood in two smart rows, a young immigrant dashed at the formation from the rear. Pausing a few steps away, he fumbled with a parcel and raised it chest-high. “There was a splutter of sparks,” a witness said, “and then an explosion like the report of a 6-inch gun.” Through the smoke, the unharmed officers sought their assailant. They found him, a Russian-born anarchist, wounded on the pavement. His hand had vanished and half of his body was in tatters. The bomb—a brass bed knob crammed with broken nails, nitroglycerin, and gunpowder—had detonated a moment early.

“A second Haymarket horror was averted yesterday by the narrowest of margins,” the Tribune reported the next morning. Woods took charge of the investigation; his detectives sped through the city after leads. One of his first measures was to arrest Alexander Berkman, who had had no connection with the riot and who was released with a warning from the magistrate.

An anarchist bomb in Union Square.

But if Woods’s first instinct was punitive, on reflection he had come to a different understanding of what had occurred at Union Square in 1908. The police, he realized, had initiated the violence by storming a peaceful rally. At one point, a protester had demanded that Inspector Schmittberger respect his right to free speech. The veteran officer had motioned icily with his baton and said, “The club is mightier than the Constitution.” The quotation had become a rallying cry for the radical opposition, and the whole affair had turned into a political embarrassment.

Six years later, as he took up the commissionership himself, Woods recalled the lessons he had learned. Although certain newspapers were calling once again for repressive measures, he had the confidence to follow his own experience. On his second day as commissioner he addressed the upcoming demonstration, meeting with Lincoln Steffens to discuss a possible truce and making reassuring statements to the newspapers. “The fact that a man talks on the subject he is interested in, and even uses profane language in punctuating his remarks, is not a breach of the peace,” said Woods. “The speakers will be allowed to do their oratorical best if they do not violate the law. I do not expect any trouble.”

Rather than sending hundreds of menacing police, he assigned just a few officers to the square. McKay had exhorted the troops to “Break ’em up!” Woods instructed his men to adopt a radically different approach. “It was pointed out that the crowd would undoubtedly be most provocative,” Woods later recalled of the briefing he gave to his men,

that many in it would try to make themselves martyrs and desired nothing more ardently than to have the police assault them; that they would tempt the police to take what would seem to be the initiative. It was explained to the police that their great effort should be to prevent trouble. If trouble should arise they were to suppress it, and to use whatever force might be necessary for suppression. But their aim was to be to prevent it from arising … Beyond this, however, they were charged with the duty of radiating good nature, of trying to maintain an atmosphere of quiet and calm. For a smile is just as infectious as a sneer.

Most of the city expected bloodshed at Union Square. The agitators were hinting at more trouble. “What are we going to do Saturday, huh? You wait and see.” The Socialist Call warned its readers to stay away. Big Bill Haywood refused to attend. A rumor circulated that the anarchists had recruited gunmen from around the nation to retaliate if and when the police made their assault. Anticipating a spectacular battle, the World assigned a special correspondent to the scene—John Reed.

By two P.M. on April 11, thousands had already gathered. They arrived in separate groups, organized and ardent. The unemployed marched in from one direction. Anarchists appeared as a separate unit. Men wore hatbands that said BREAD OR REVOLUTION. Speakers attracted attention in all parts of the square. “The whole place was murmuring and boiling with low-voiced propaganda,” Reed reported. “Free speech was beginning.” “Little east side radicals, quacks, social service workers and even politicians were the centre of eager little tight-packed groups, arguing and preaching … One saw Lincoln Steffens plunging through the mob … shoals of strange radical women in the Greenwich Village uniform, and others in civilian clothes. All the intellectuals were there. Then there were hundreds of Socialists, although their official daily paper had warned them to ignore the meeting. And many I.W.W.’s who had also been told to hold aloof.”

Just a few score uniformed officers spectated from the sidelines, stirring only to prevent marchers from parading out of the square. Berkman spoke and no one moved to silence him. Leonard Abbott, a founder of the Ferrer Center, proclaimed that “the whacks of the police clubs that fell upon the head of Arthur Caron a week ago have already been heard around the world.” Still, the cops kept their distance. It gradually became clear that new guidelines were in effect. “These people have faith in Mayor Mitchel, and faith in the new Police Commissioner,” Abbott confessed, “and it seems to have been justified … You can fairly feel the ugliness of the crowd’s mood seeping out of it.”

I.W.W. meeting in Union Square.

Alexander Berkman in Union Square, April 11, 1914.

Woods, who had been receiving regular updates from Schmittberger, arrived just as the demonstration was breaking up. Even he was surprised at the results of his own orders. “The change of method was almost unbelievably successful,” he realized. “There was no disorder.” Emboldened, he mingled with the protesters. “I was not recognized,” he recalled. “I went up toward the crowd of one or two hundred people, perhaps, and their orator got up on the billboards, and as I went up he called out, ‘Well, boys, the cops certainly have made good today. Three cheers for the cops!’”

* * *

“WITH SUCH A man as police commissioner,” said a relieved John Purroy Mitchel, “I’ll have no police problem. I can just stick him up in headquarters and forget him.” One less cause for nerves, however, still left far too many worries and did little to ease his overall anxiety. The imperturbable “young knight in shining armor” who had taken office four months earlier had grown pale and thin; the black hair around his ears was turning gray.

Mitchel’s workdays usually began at breakfast, with one or more cabinet heads joining him in the wainscoted dining room of his apartment in the Peter Stuyvesant, an elegant building on Riverside Drive at Ninety-eighth Street. The upper-story windows looked high over the gray waters of the Hudson to the trees and cliffs on the far shore, offering a brief promise of serenity. But then the telephone would ring and city business pressed again. Downstairs, he and his subordinate would climb into the open tonneau of his automobile—the chauffeur draping a fur robe over their legs to protect against the cold—and they would accelerate out onto the drive. Often they would stop by some other commissioner’s apartment and pick him up, too, before speeding downtown to City Hall. By the time the mayor arrived at his office, he had already done an hour’s worth of work. And many nights he wouldn’t leave again until nine or ten in the evening. “Mayor Mitchel’s friends,” a concerned Sun reported in May, “say he is burdening himself with the pressure of work such as few men stand for more than a limited period.”

Mayor Mitchel en route to City Hall.

Mitchel, who prized efficiency first and last, felt himself everywhere thwarted. He employed two full-time secretaries—one for official business, another for the private obligations engendered by his position—and they each placed about a hundred telephone calls a day. Still, nothing got done. Or it was done, and then undone, and had to be done over. Newspapers magnified any misstep into a ruinous lapse, and saw disaster in every portent. If there happened to be a real problem—as, for instance, with the unemployed—it was inevitably exacerbated by the press. It felt as if his five and a third million constituents had nothing to do but lodge bitter complaints, request impossible favors, waste his days with eccentric schemes. He received between two hundred and three hundred letters a day, asking for matrimonial advice, offering headache remedies, challenging him to a tango competition. “Quite a lot of time of this office,” he complained to an interviewer, “is taken up by matters that never ought to come before the Mayor at all.” Unable to mask the frustration he experienced around constituents, he became increasingly impatient, “and not seldom too curt,” with citizens who behaved “captious and unreasonable.”

Doctors had promised that his migraines would gradually diminish, but thanks to the stress of his responsibilities the attacks were in fact occurring with greater frequency and severity. His bodyguard would find him in his office, prone on the couch, head in hands, in “bending pain.” On the worst days, he would vanish into a secret hideaway in the Municipal Building to recover alone. In March, a headache forced him to retire from a meeting of the Board of Estimates. When newspapers published exaggerated articles about his “collapse,” the mayor warned reporters: “If you are going to write such stories, you will have to do it about twice a month.”

There were an estimated two hundred thousand “mental incompetents” in the country, and a disproportionate number of them, it seemed to Mitchel, must have been resident in the five boroughs. The city had an inexhaustible stock of neurasthenics, dipsomaniacs, hypochondriacs, and plain old “bugs”; “There are thousands of people who write threatening letters,” Mitchel testified. “The Mayor is always receiving threatening letters.” Of course, the majority were harmless, and there was really no way to protect against the rest, anyway. But he couldn’t completely ignore them. His predecessor, William Gaynor, had been shot in the throat by a deranged assassin; the wound had festered for years before killing him. With a growing sense of his own vulnerability, Mayor Mitchel took to carrying a revolver in a shoulder holster whenever he ventured out on public business.

IT WAS ABOUT one P.M. on April 17 when Arthur Woods appeared in the mayor’s office. While they prepared to leave for lunch, he described the scene of a lodging house fire he had just toured. Together with Frank Polk, the corporation counsel, and George Mullan, Mitchel’s former law partner, they left the building, descending the marble steps onto City Hall Plaza. The afternoon was cloudy but warm, and the old elm trees were just showing yellow buds. Office workers on their midday break jammed the square. A group of socialist orators gathered, as always, around the plinth of the Benjamin Franklin statue. As the officials walked south toward Park Row, many in the crowd paused to get a close look at their mayor.

A police department automobile was idling at the curb. Mitchel clambered first into the narrow rear seat, followed by Polk and then Mullan. The chauffeur reached across to cover them with the fur robe. Woods, who was to ride up front, ventured round to the street side, carefully avoiding the nearby trolley tracks. A shabbily dressed old man approached, threading through the traffic. Woods stepped onto the running board and was about to climb inside. The old man had reached a distance of about five feet. He raised an arm, revealing a snub-nosed revolver. Woods, two jumps away, was already in motion when the first round fired. There was no second shot. Woods, an expert in jujitsu, grabbed the attacker by the shoulder, tackled him to the ground, and pinned his arms.

In the car, Mitchel thought for a confused moment that he had heard a muffler explosion. But then he felt the burning in his ear. To his right, the corporation counsel coughed blood and teeth. The mayor was unscathed except for some scorches from the gunpowder. Gathering himself, he drew his blue-gray revolver, enraged, eager to retaliate. He made a survey of the crowd, looking for assailants, hoping to trigger off some revenge. But Woods and the chauffeur had disarmed the shooter. They had him on his feet and were leading him away. Thousands of civilians were mobbing the car. Police whistles blared from every corner, and Polk was gagging with pain. Mitchel, still brandishing his gun, supported the wounded man back inside City Hall. Even then, in the throes of excitement, he was already experiencing relief. For months he had anticipated this moment; the burden of dread had grown excruciating. Finally, instantaneously, it had been removed, and he could proceed with the work he had to do.

The assassin fired from about five feet away.

Only a few hours later, the mayor faced an audience of hundreds at a Press Club dinner. “Calm, smiling, cool,” he displayed “a jaw of steel,” wrote a witness, and was “totally unlike a man who had escaped a funeral.” He rose to speak, and the thankful crowd offered a five-minute ovation before he could say a word. “The experience of this afternoon is, of course, one to impress itself on any man’s mind,” he began. “I had been almost expecting some such thing, not because I had any reason to expect it, not because there is any reason why such a thing should happen in a civilized community ordered by laws, as is ours, but because I know that life in a democracy, where there is progress, where new things are being established, is more or less of a battle and in a battle almost anything is likely to happen.”

It was midnight when the mayor eventually got home to Riverside Drive. By 8:30 A.M. the next day, he was already dressed and breakfasted. Riding the elevator down to his waiting auto, Mitchel arranged himself to confront the business of a new morning.