On May 3, 1903, he parades through a perpetual ovation. Stock-ticker tape slips in helixes through the skies from Bowling Green to Trinity Church, and confetti cloaks his uniform. The jammed spectators at Houston Street refuse to let him pass until he tips his cap three times to them. Every block reserves its loudest huzzah for his approach. From both sides of the boulevard, they surge against the police line, stamping and calling out, “Max!” “Schmitzy!”

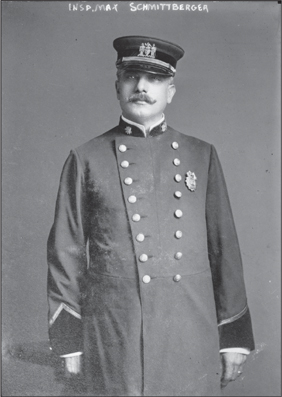

Eyes front, Inspector Max Schmittberger nudges his horse from Fortieth Street onto Fifth Avenue. After twenty-nine years of service, he is still the “Police Samson,” a “big, burly six-footer.” In the late-afternoon light, the brass buttons and gold oak leaves on his coat no longer shimmer as they had at midday, but his gloves and cap remain pure white. A fine hussar’s mustache overtops his small, tight-lipped mouth. He wears the Prussian Order of the Black Eagle and has invoked the diktats of Field Marshal von Moltke to many a subordinate. Even on station duty he demands a crisp salute. The handiest horseman in the department, he is its truest sharpshooter and “an artist” with a baton. “He is not only the equal of any man on the force,” a former chief declared, “but I cannot think of any one who is his equal.”

The reviewing stand is in Madison Square, near the foot of the new Flatiron Building. The police commissioner and mayor are in the first row on the flag-strewn platform. Distinguished guests are massed twenty deep, and the colorful din belittles all that has preceded it. Schmittberger draws even with the dignitaries. For nearly a decade, these men and their predecessors have humiliated and ostracized him. They have “cuffed and cursed” him, accused and slandered him with “nasty and vindictive” attacks. Until this year—his year of redemption—they have forbidden him even from marching in the annual policemen’s parade.

Max Schmittberger.

He turns his blue-gray eyes on them. He salutes. And then, eyes front.

* * *

SUCH CURSES HAD covered him in the previous decade, such obloquy and derogation. The newspapers called him “liar” and “grafter.” Churchmen took him for a “thief and a crook.” An “everlasting disgrace,” said the district attorney. Socialists jeered him as an anarchist, and anarchists warned he was a “marked man.” His fellow policemen—the honest and dishonest alike—loathed him, one and all. He was “Judas,” a squealer who had “split on his pals,” and many officers refused to serve under him. He should be in Sing Sing, not in uniform, ran the everlasting outcry. “Schmittberger will never do police work of any kind again.” “Schmittberger will get a hard drubbing.” “Schmittberger has got to go!”

A DECADE EARLIER, in 1894, he had been a recently promoted captain with a record “unmarred by a single complaint.” He was a shrewd and patient investigator, a fearsome pugilist, and a modest subordinate who had personally accounted for nearly a thousand convictions and had arrested more murderers than any other man in uniform. And, like every other officer of his rank on the force, he was corrupt, in a good-natured sort of way. He would collect payoffs for his superiors and rake off his due portion. He was selective about the brothels and illegal saloons he busted up: Proprietors who were paid up with the police tended to stay in business longer than those who fell behind. It wasn’t corruption so much as it was tradition. These were established practices, and Schmittberger was a firm believer in upholding them.

Sometimes the private business of the System would escape the shadows into the public eye, and then the reformers would be involving themselves. Every ten years or so, some impaneled bluebloods came around scratching for trouble. In 1894 it was the Lexow Committee, state investigators hoping to irritate the city bosses. It looked, at first, to be the usual nothing: a circus for the papers, a political career for a prosecutor, some catharsis for the Society for the Prevention of Crime. But witnesses sometimes say funny things—like, in this case, about handing a $500 bribe to a captain named Schmittberger. Subpoenas ensued. Still, even this was no source of worry; the captain was known as a dependable fellow with a small mouth, the taciturn type.

Nevertheless, every seat was occupied in room 1 of the Tweed Courthouse on the morning of December 21, 1894. A long delay heightened anticipation, and a “loud buzzing” greeted Schmittberger’s entrance. He wore civilian clothes and had “dark rings about his eyes, which told of sleeplessness and mental suffering.”

Q: You are a police captain of this city?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: In command of what precinct at the present time?

A: The Nineteenth.

Q: Now, captain, you are called here as a witness on behalf of the State of New York to testify in relation to matters in the police department of this city … you appreciate the obligations which rest upon you, do you?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: You know that the oath administered to you is binding absolutely upon your conscience?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: To tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth?

A: I have come here to tell the truth wholly and truly, without any promise of any kind.

No more buzzing. “Half a dozen police captains who were in the room opened their eyes wide, and bent forward to hear what was coming next.”

And then Schmittberger talked. He tallied the bribes he had taken, the payoffs and political contributions he had disbursed. He explained how patrolmen purchased their appointments and then paid again to be promoted. He sketched the system of coercion and collusion, from chief to roundsman, that was ruining discipline in the department. And he revealed the crowning exposure of all: that protection for any “vice and crime” in the city could be purchased at an established price. When he had told enough to fill seventy pages of testimony, he descended from the stand, a “broken man.”

At every place where New Yorkers gathered to talk, they spoke that night of Schmittberger, “in all the hotel corridors, the social clubs, the political organizations, the theatres, the fine cafés in the fashionable streets and avenues and the rumshops and ‘dives’ of the East and West side.” The lone exception was 300 Mulberry Street—police headquarters—which wreathed itself in silence.

* * *

HE “WAS A villain in two ways, in two worlds,” wrote Lincoln Steffens, his friend and adviser. “The good were against him for his grafting, the underworld for squealing.” Schmittberger remained with the department, as an outcast. He was stripped of his posting in the glamorous, roaring Tenderloin and sent to the wasteland of the Bronx, where “the chief business of the police is said to be watching for stray goats.” Languishing in Goatville, he waited for the officers he had exposed to get their transfers to Sing Sing. But no indictments appeared. The worst of the thieves retired on comfortable pensions. All the rest retained their rank and standing, determined to see him break. His “years of purgatory” had begun.

AT THE DINNER table, in his apartment on East Sixty-first Street, his eight children sat in silence. They nudged one another, passing the question along to the oldest son. “I say, Pop,” he blurted out at last, “is it true this stuff they are saying? It’s all lies, ain’t it!”

He would redeem himself through labor. He followed cases overnight, two nights in a row, stealing home after sunrise to burgle a few hours of sleep. Newspapermen found him composing reports simultaneously on seven different typewriters. He was a good cop, and these were not so plentiful. Antivice forces could not afford to waste an honest police captain who was estranged from the System and desperate for forgiveness. They pardoned his faults and convinced themselves of his repentance. Theodore Roosevelt, in his years with the police, used Schmittberger as a “broom” to sweep out whatever districts his constituency happened to find most appalling. The Reverend Charles Parkhurst, whose Society for the Prevention of Crime had urged on the Lexow investigations in the first place, met with him almost daily to discuss the condition of his conscience. But the reformers never lasted longer than one election. The Tammany men always returned, and then Schmittberger’s torments would begin again.

Early in 1903, Schmittberger took the exam to qualify as an inspector, scoring higher than any other captain in the rolls. His opponents rallied their last reserves to slander him. But his repentance and redemption had won the “support of the best people in the country.” Roosevelt, now president of the United States, wrote him a letter of endorsement and shook his hand in public during a visit to New York. With no other recourse, the police commissioner regretfully granted him an inspectorship.

The triumphal procession in May 1903 was his reward. When the multitudes cheered his apotheosis, they also celebrated the charity of their own forgiveness. Their clemency had lifted him up again to the position he had forfeited. They had redeemed him, themselves, their city. Applause from the Battery to Madison Square, huzzahs from here to heaven: It could never be too much.

IN 1909, WHEN he alone remained from the scandalous nineties, he was promoted to chief inspector, the city’s highest-ranking uniformed officer. “I think I can safely say that it has been a long, hard fight, honorably and honestly won,” he said. “Victory has come to me because I have ‘made good.’”

After nearly a decade as chief inspector, Schmittberger caught cold while watching a Liberty Loan parade. When he died a week later, the flags at every precinct in New York marked mourning for the “Grand Old Man” of the police department. Thousands followed his casket to St. Patrick’s. Mayor Mitchel and Commissioner Woods marched in the procession. As did Frank, his trusted mount. After Schmittberger’s death, reporters found in his apartment half a dozen rooms crowded with commendations and trophies, ornaments from foreign governments, his Slocum Medal, notes of thanks from the neighborhoods he had patrolled. And, on his bookshelves, intermixed with the rest, the five black volumes of testimony from the Lexow Committee hearings.