After the magistrate had disclosed his sentence, Frank Tannenbaum, the dangerous I.W.W. agitator, returned to his cell in the Tombs Prison to settle some outstanding business. He asked a comrade to please return a library book he had borrowed. And he scrawled a quick note to his mother and father.

Dear Folks,

I have just been committed to serve 1 year in jail. Don’t worry. My friends will take care of me. I will not be able to write to you, only once in a few months. But when I come out I will spend some time at home. With regards to all at home.

I remain your loving son, F. Tannenbaum

That done, he was ready for transportation.

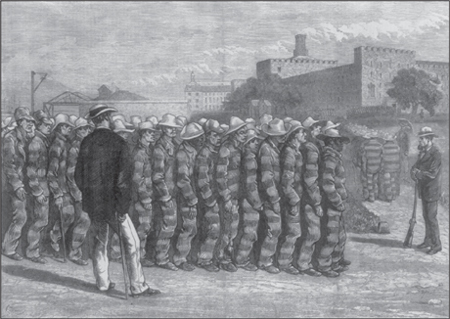

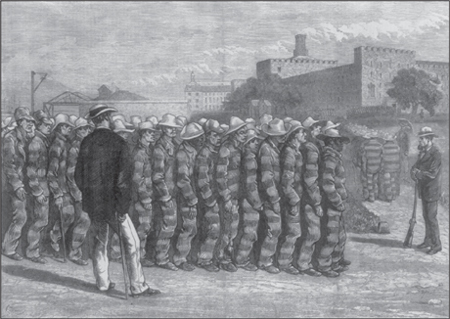

Guards bused him from the jail to an East River dock and led him down the gangplank to a Department of Correction ferry. From there it was just a short steam upriver to Blackwell’s Island, where he marched in a column across the yard toward the administrative building. In the photographic room, he was ordered to undress and was slammed down into a chair. A keeper slapped an iron hood over his head, barking, “Stretch your arms!” “Put out your foot!” while posing him in various positions. Then he was issued prison stripes, coarse undergarments, and a filthy blanket before being led to a shadowy three-foot-by-seven-foot cell, possessing neither toilets nor windows.

Until then, none of Tannenbaum’s experiences had affected his inner man. Through it all, he had remained “aggressive, defiant, uncompromising.” In the Tombs, he had enjoyed amiable relations with the guards, and even the wrathful magistrate had treated him with a certain respect. Now—hooded, prodded, and penned on the island—he finally felt the burden of circumstances. “I had ceased to be a human and had become a number,” he recalled. “For at least the next few hours I was the most humble, obedient, I might almost say the most broken-spirited person imaginable.”

Blackwell’s Island did that to people. A narrow two-mile-long shard of earth between Manhattan and Queens, it was blessed with refreshing breezes, as well as lawns and gardens that made it “one of nature’s beauty spots.” Reformers spoke of turning the whole area into a park, and Jacob Riis prophesied that someday it would be “the most marvelous public playground in the world.” In the meantime, the city had found a different use for it. Since the early decades of the nineteenth century, the island had served as a quarantine for New York’s sinners and sufferers. Charity and smallpox hospitals, asylums, orphanages, prisons, and almshouses interposed themselves among the fields and forests.

Prisoners returning from work on Blackwell’s Island.

From the water, these solemn structures made a “fine show,” and the penitentiary in particular had “the pathetic beauty … of an 18th century print.” But any grandeur vanished on acquaintance. Within the picturesque walls, inmates discovered “conditions in daily operation quite at variance with the dictates of humanity and the ordinary laws of health.” In the 1880s, Nellie Bly had spent ten days in the madhouse on assignment for the World. Riis had devoted a chapter of How the Other Half Lives to “The Wrecks and the Waste” of the charity wards. Through these revelations, the island had acquired indelible connotations of brutality and squalor. It was a way station toward purgatory. “When they move out of the Fourth Ward they will move into Bellevue Hospital,” went a typical jeremiad, “when they move out of the Bellevue Hospital they will move to Blackwell’s Island; when they move from Blackwell’s Island they will move to the Potter’s Field; when they move from the Potter’s Field they will move into the darkness beyond the grave!” By the twentieth century, the name was so blemished that the newly constructed Blackwell’s Island Bridge was quickly renamed the Queensboro, and an effort was gaining impetus to rechristen the island itself.12

A few days before Tannenbaum’s arrival, Commissioner of Correction Katharine Davis had presented Mayor Mitchel a report on the penitentiary, revealing a facility dysfunctional in every facet. The cornerstone had been laid in 1828, and the buildings had long since become obsolete. With an intended capacity of eleven hundred inmates, the actual population averaged around eighteen hundred. Cells were “wet, slimy, dark, foul smelling, and unfit for pigs to wallow in.” Hardly large enough for a single person, overcrowding meant that more than half of these chambers held two occupants. Treatment of the prisoners was “vile and inhuman.” On the whole, Davis concluded, the facility “belonged to an era of general political unenlightenment that was long out of date.” In her opinion, the entire edifice should be abandoned as soon as possible, and emergency renovations totaling $32,000 had to be pursued immediately.

Prisoners’ sentences ranged from one to twelve months, meaning thousands of inmates cycled through the penitentiary each year. Though new people arrived daily, outside contact was strictly curtailed: Convicts were allowed one visitor each month, and there were harsh limitations on correspondence. Pencils and newspapers, toothpaste and soap, were contraband; it was against regulations to hang a photograph on the walls. And it wasn’t even necessary to commit a violation to receive discipline. “If a keeper doesn’t like your face, he punishes you by standing you against the wall, depriving you of food, or shuts you up in the cooler.”

Despite all this, Tannenbaum’s initial discouragement did not last long. Discovering a camaraderie among his fellows, he soon returned to the accustomed role of instigator. “No matter how many rules you make in jail,” he soon learned, “the men will find a way to break them.” Before his first day had ended, he himself had transgressed every one. Stolen newspapers were passed around until they fell to pieces. Underground networks smuggled letters in and out. Within a few hours of his arrival, Tannenbaum had already received several illicit notes through these secret means. “My dear Frank,” a note from Alexander Berkman began,

Need I waste words to assure you of my deepest sympathy? You have acted like a Man, and that is the very highest I could say—as a man and true revolutionist. Never mind the barking of the curs—it is their insignificance + cowardice.

I am proud of you. For I am sick of the crawling and kowtowing—before the court—by those who are so loud when it is safe to be. The time has come when we need, most urgently, men—men who will measure up to the need of the hour and stand up as men at the critical moment.

When you get a chance, let us know how you are getting along + how you are treated. You have friends who will remain true to you + who will not stand for any abuse of you by the authorities …

Fraternally,

Alex Berkman

Frank had arrived on the island with a reputation as a troublemaker, and it did not take long for him to confirm it in the minds of his keepers. Every time the guards passed his cell, they discovered him reading an illicit newspaper. Finding the prison library needlessly inefficient—inmates had no choice in what books they were issued, and were often presented with volumes they couldn’t read—he volunteered to reorganize the meager assortment. “Any time, Tannenbaum,” snapped Warden Hayes in response, “that we want your help to run this institution, we will call for it.” Soon, however, he was amassing a private collection of his own. The way the newspapers had portrayed him, as “only an ignorant boy,” had renewed his commitment to educating himself. “I determined,” he recalled, “no one ever again could call me ignorant of the education of books, no matter what the cost.” He had left his supporters a list; the first consignment of materials contained dense tomes on economic and political theory, including several works by Peter Kropotkin, the Russian anarchist. Tannenbaum would spend his time in prison studying the theories of revolution that he had already attempted to put into practice on the streets.

At the same time, his correspondents kept him informed about their progress. “We held a fine meeting at Franklin Square today,” a friend wrote. “At Rutgers Square meetings are being carried on regularly.” After the riot in Union Square, he read that “Gegan and Gildea as usual were on the job. The police bore down and beat up the crowd and arrested O’Carroll … and Caron and several others.” In this way, he also was able to follow the continued violence in the coal regions of Colorado. And he learned of growing tensions between the United States and Mexico. As Tannenbaum’s days passed, however, more and more of his correspondents began excitedly to discuss the next big local event, “a giant protest meeting to be held at Carnegie Hall on April 19.”

* * *

NEW YORKERS WERE by now accustomed to wake each morning and find another headline describing the latest provocations by the Industrial Workers of the World: I.W.W. DEFIES POLICE, I.W.W. FREE SPEECH TO BE INVESTIGATED, I.W.W. SLURS MAYOR: CALLS HIM “BELL HOP.” Considering that the local chapters had been nearly defunct at the start of the year, this could have been seen as a triumph of propaganda. “For two months and over the I.W.W. has kept itself on the front page of the metropolitan dailies, and that surely is going some,” a comrade boasted in a letter to Tannenbaum. “Now, of course, if it were Carnegie’s Peace Society or Rockefeller’s Educational Board, that would be different. Their every meeting, their every proceeding, would be reported if so desired. But the I.W.W., never!”

The publicity had done little, however, to clarify the actual goals or doctrines of the Industrial Workers of the World. Politicians and newspapers were content to affix the I.W.W. label to the unemployed, the anarchists, or any of the city’s other radical leagues and councils. The Wobblies were “credited with the doings of everybody, no matter whom, so long as the doings take on the appearance of the I.W.W. in the editor’s mind,” Tannenbaum’s correspondent wrote, and if trends continued, “the Republicans and the Progressives will yet get to be classed with the I.W.W.s.” It was infuriating to the socialists and trade unionists whose actions were continually attributed to their rivals. And to those who feared that agitators posed a real threat, the willful misidentification seemed to verge on recklessness. “It will be very much to the advantage of the conservative people of this town to learn more than they have yet taken the trouble to learn” about the I.W.W., a Times columnist urged. “It is always to the advantage of a person who is attacked to know why he is attacked, who is attacking him, and where he may expect the next blow. And this is an attack—an attack on the social system. Its aim is nothing less than revolution.”

But it was the radicals themselves who finally took steps to rectify these misperceptions. “We wanted to present our aims to the public dramatically,” an organizer recalled. Assuming “that everybody really wanted to hear the truth about labor,” activists began to promote an educational evening at Carnegie Hall. Unlike the street demonstrations, where multiple speakers competed in issuing contradictory statements, this occasion would offer a single coherent message. There would be no sensationalism or controversy. The biggest difference of all: There would be no scare headlines the next day.

Handbills and posters advertised the topics to be discussed: “The outrages at Union Square … The outrages at Trinidad, Colorado … the severe sentence inflicted upon Tannenbaum.” To afford the theater, and to raise money toward paying Frank’s $500 fine, the organizers had to charge admission. For a quarter, spectators could pack into the gallery; a dollar afforded a box seat. Promoters canvassed Manhattan, selling tickets to chorus girls on Broadway and to officials at City Hall. When Lincoln Steffens suggested peddling some on Wall Street, one of the volunteers borrowed a presentable coat from Mabel Dodge and managed to sell several seats to the J.P. Morgan Company.

By 8:15 P.M. on the evening of April 19, Carnegie Hall had begun to fill with a curious assortment of people. “Although the crowd was small,” a witness observed, “it amply made up for that deficiency in enthusiasm and variety.” Actresses in cerise evening cloaks milled about the lobby while laborers looked starchy in new-bought suits. Steffens and Mrs. O.H.P. Belmont, a noted suffrage advocate, attended, as did “practically everybody in I.W.W. and anarchistic circles.” About one third of the audience was in stylish evening dress, and if some of these had a serious curiosity, most had come on a lark, “obviously hopeful that something would happen, something lively but not too strenuous.” Police Commissioner Woods, who had reserved a prime, first-tier box, casually appraised the scene, laughing when a pretty usher put some radical literature in his hand. Chief Inspector Schmittberger commanded a detail of nearly a hundred men, but the directive to “keep peace with a smile” remained in place, and the police were in gentle temper. Not that they had neglected their preparations; reserves stood ready at the Forty-seventh Street precinct, and “the block would have swarmed with them at the blowing of a whistle.”

Fashionable couples were still filtering in from dinner when Max Eastman, editor of the Masses, called the meeting to order. The stage was crowded with martyrs of the movement, including Joe O’Carroll, Arthur Caron, and Becky Edelsohn. To accurately convey the feeling of an authentic I.W.W. meeting, the program began by putting two resolutions to the vote. The first concerned the injustice of Frank Tannenbaum’s sentence, and it was ratified easily. Only two nays were heard, and both came from occupants of the J.P. Morgan box. The second resolution, opposing the looming war with Mexico, sparked pandemonium. “In a few minutes the hall was in an uproar, men shaking their fists and shouting that there should or should not be war, according to their ideas.” The carefully scripted pageant edged toward disarray, but it was not yet lost. Big Bill Haywood was the next speaker, and the audience quieted while he shambled toward the rostrum.

No one else was so identified with the I.W.W. in the public mind. Haywood, a journalist for Metropolitan magazine had written, was the “prophet of Industrial Unionism, leader of all poor devils.” A youth spent in the hard-rock mines of Idaho had left him with one eye, “the physical strength of an ox,” and a “face like a scarred mountain.” Now forty-five years old, he still affected a black Stetson and cowboy twang, but he had forsworn his old.38 Colt. If the Big Bill legend persisted, the man himself had mellowed. “Haywood is long on talk, but short on work,” sneered the bulletin of the Western Federation of Miners, a union that had expelled him. The Sun was even less sympathetic. “When bullets are flying in Colorado, Big Bill is in New York,” an editor wrote. “When heads are being broken in Union Square he is detained elsewhere; when anybody starts a fight Big Bill is recorded among the absent.” In labor circles, it was murmured that Haywood had gone soft through spending too much time around the bourgeoisie. The “two-gun man from the West” now kept an apartment down on West Fifteenth Street and was a fixture at Mabel Dodge’s evenings. He preferred discussing poetry to politics, and could sometimes be found sitting on the benches in Washington Square, scribbling out verses of his own.

Big Bill Haywood, the face of the I.W.W.

At the moment, a lecture on the future of proletarian painting or a rumination about the poetry of work would have entirely satisfied the organizers who had staked so much on the Carnegie Hall meeting being successful. Anything would do, so long as it helped to ease the “undercurrent of feeling” in the theater that had manifested itself as soon as the discussion turned to Mexico, and which now “threatened to break out at any time.” But Haywood chose this opportunity to flash some of his old belligerence. He decided to talk about Mexico.

“Sherman said, ‘War was Hell,’” he bellowed. “Well, then, let the bankers go to war, and let the interest-takers and the dividend-takers go to war with them. If only those parasites were out of the country it would be a pretty decent place to live in.” The laboring classes would never support President Wilson’s imperialism, he continued. “The mine workers of this country will simply fold their arms, and when they fold their arms there will be no war.” Three sentences into his speech, everyone was shouting. From the galleries came cries of encouragement. Derision raged from the boxes. “You may say that this action of the mine workers is traitorous to the country,” he shouted back, “but I tell you it is better to be a traitor to a country than to be a traitor to your class.”

When he lumbered away from the podium, any potential for reconciliation that evening had disappeared. The next morning, New Yorkers would wake to the usual array of panicky headlines: IGNORE CALL TO WAR SAYS BILL HAYWOOD, STRIKE THREAT IF WAR IS DECLARED, HAYWOOD OPENLY STIRS SEDITION.

THE ATTORNEY GENERAL in Washington, D.C., proposed filing an indictment against Big Bill, newspapers demanded reprisals, and even labor leaders rushed to distinguish their positions from his. But Commissioner Woods calmly refused to overreact. He had heard every word spoken at Carnegie Hall, and as far as he was concerned nothing had crossed the boundary separating free speech from sedition.

Meeting in Mayor Mitchel’s office on April 22, Woods had other matters to discuss. Commissioner Polk was healing well after surgery to mend the wounds he had received in the murder attempt. At first it had been supposed that the gunman from the previous week had been a radical assassin, with Alexander Berkman and his cadre the most likely source. “The Anarchists have no particular feeling against Mayor Mitchel, and do not consider they have any feud with him,” Berkman had insisted. “Anarchists do not resort to assassination for fun, and the only time when it might occur would be when an individual Anarchist in a time of great political or revolutionary excitement might select a much-hated man for a mark.” Although this may not have been wholly reassuring to authorities, a short interrogation of the shooter satisfied them that he was no radical, but rather an unstable former city employee with a grudge. Currently, he was under the supervision of alienists in the Tombs, and a transfer to the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane was imminent. Mitchel asked Woods to examine any more messages that arrived from “nuts,” and also suggested “a plan for looking up the writers of threatening letters and committing them to Bellevue.”

Among other immediate topics, Woods and Mitchel had to consider the local impact of a looming war with Mexico. After more than a year of idleness—Woodrow Wilson called it “watchful waiting,” while his opponents preferred to think of it as “deadly drifting”—military intervention was now at hand. Finally convinced that action had become a moral necessity, the president had deployed the North Atlantic fleet to blockade the Gulf Coast city of Veracruz. He would deploy force of arms not for conquest or profit but out of compassion. The specific incitement—a minor diplomatic transgression, for which the Mexican government had speedily apologized—hardly mattered now that he was bent on war. The important thing was the greater message his new decisiveness would impart. “I hold this to be a wonderful opportunity,” Wilson explained, “to prove to the world that the United States of America is not only human but humane; that we are actuated by no other motives than the betterment of the conditions of our unfortunate neighbor, and by the sincere desire to advance the cause of human liberty.”

If fighting began, repercussions in the city would go far beyond Haywood’s speech. And indeed while the two officials spoke, the first dispatches started to arrive from Veracruz: FIRING COMMENCED AT DAYBREAK. SHIPS NOW SHELLING SOUTHERN PART OF CITY. The long standoff between Mexican leaders and the U.S. government had finally erupted in gunfire. Personally, Mitchel thought the affair had been bungled. Woodrow Wilson had dithered for months instead of taking action. The mayor would have opted for a direct declaration of war weeks earlier. But now that troops were committed, he wired Washington immediately, promising the president that “the people of the City of New York are with him and behind him in this crisis.” Locally, it would mean political posturing—Tammany Hall had just announced it would be raising a regiment of its own—antiwar protests, angry tempers, and patriotic outbursts. Recruitment centers would be jammed; the Brooklyn Naval Yard would have to expand operations.

While they talked, the officials heard some sudden commotion coming from outside the building. Commissioner Woods rushed out to City Hall plaza, where he found a mob of a thousand people roiling round the statue of Benjamin Franklin. They circled the area, pressing in almost to the pedestal, where some unseen instigator plied his trade. Calling the reserves from the Oak Street precinct, Woods forced his way through to the front of the crowd. And there he found Becky Edelsohn antagonizing the throng of hecklers.

At that moment he joined a widening circle of city residents suddenly concerned about her activities. “It is little more than a month since the newspapers began printing the sayings and exploits of one Becky Edelsohn,” the Tribune announced. “Besides being an agitator, who and what is this person who, bursting out of obscurity, has caused more editorial comment for and against than any woman since Emma Goldman? … What has this young girl endured to make her ready to outface street rowdies, to criticise the government and laugh in the face of recognized authority?”

Becky was young and shocking. “She was a tremendously fiery person,” a friend recalled, “always two steps ahead of Berkman or Goldman.” Her good looks and bright red stockings made a striking impression. “She was five feet four inches tall,” a comrade recalled, “moderately plump, with black hair; she was very pretty—beautiful I should say.” But most people remembered her for her fearless self-possession. “Becky’s eyes,” a reporter wrote, “were built to flash, not to weep.” In court, she once leveled her hardest stare on a judge who tried to silence her. A member of the audience caught the look. “I knew she was not one of the inarticulate mass,” he later wrote, “but a girl with power.”

Born in Ukrainian Odessa on Christmas Day 1892, she had come to the United States with her family two years later, and had battled with parents, teachers, and everyone else who claimed authority ever since. She spent a year in high school and tried to train as a nurse, but in each instance had found the discipline unbearable. An elder brother introduced her to politics, and she soon became one of the many strays gathered up in Emma Goldman’s extended family of anarchists. She left her family to live with the radicals at the age of thirteen, and a year or two later, in 1906, she had her first chance to display her antiauthoritarian inclinations. When cops raided a protest meeting, the Tribune recounted, she “was roughly handled and put under arrest, because she failed to leave the hall as quickly as ordered.” Though she was still “a little girl with short skirts,” she was accused of assaulting a policeman. The magistrate took one look at the 250-pound arresting officer and dismissed the charges.

She was fifteen when Alexander Berkman, then in his late thirties, was released from prison. Becky comforted him through his first years back in the world, and before long they had become lovers. This was the first of a series of relationships. Becky’s sexuality exerted a fascination on outsiders, who let their lascivious imaginings cloud their appreciation for her leadership abilities. A clandestine informant who infiltrated the radicals’ circle sniped to handlers that Edelsohn had a “reputation among the anarchists of being able to be ‘intimate’ with more men in a day than any woman.” She underwent an abortion in 1911, and though this would not have been a scandal in the circles she frequented, her general behavior had led to some disquiet; “her lack of responsibility and perseverance in her personal life,” Emma Goldman would later write, “had for years been a source of irritation to me.”

Now, at the Franklin statue, she was doing her utmost to irritate the hostile crowd.

“It’s all a frame-up by the capitalists,” she was yelling, “so that good workingmen’s blood will be spilled to protect the investments in Mexico of Hearst, Rockefeller, and the Guggenheims.”

“Ah,” people were laughing, “cut that out, kiddo.”

“Show your American citizenship papers,” someone called. “And if you haven’t got ’em, then shut up.”

“How many of you would fight for the flag?” she asked.

Every hand shot into the air.

“A flag isn’t anything to fight for!” she cried out. “The American flag isn’t fit to defend!” No one was laughing anymore. Clerks and office boys shouted her down. “Hooray for Wilson!” they called. “Hooray for the flag! Down with the greasers and the I.W.W.!”

“Lynch her!”

“Kill the reds!”

Rotten fruit started flying round her head. “War is hell,” she yelled, “but when you attack a poor little woman like me it is worse than hell!” The mob pressed forward until it had her pinned against the railing at the base of the statue. And at that moment—“just in time” to save her “from rough treatment”—the Oak Street reserves appeared. “The police formed a flying wedge” and pushed up to the center of the ruckus, “shoving the crowd back, using their sticks now and then as persuaders.”

Officers lined up in front of Becky and some other speakers, cordoning them off from the hostile throng. The captain urged the radicals to make their escape, but, led by Becky, they refused to desist. They would test the police department’s commitment to free speech in the most dramatic way possible. For the next hour, the speakers railed against the war while the police held off the crowd. Finally, the spectators had had their fill: “Lashed to fury by the tongue of Reba Edelsohn,” they attempted one last sortie, charging the cordon, squirming between the uniformed officers. No longer able to protect either the speakers or his own men, the captain ordered the anarchists’ arrest. Most submitted meekly, but when a six-foot-tall patrolman tried detaining Becky, she struggled so ferociously that a paddy wagon had to be called in to transport her to the precinct.

A COUPLE OF weeks earlier, police had trampled and clubbed dissenters into the hospitals. Now officers were risking their own safety to assure that all points of view were heard on the city’s streets. “In New York,” Arthur Woods would later tell an investigating committee, “we not merely permit free speech and free assemblage and picketing, but we protect it.” In less than two weeks as commissioner, he had already done much to prove the truth of this statement. He was establishing a novel set of protocols; no longer would the policeman be the instinctive enemy of the protester. Demonstrations would be condoned as long as they did not incite listeners to immediate acts of violence or seriously impede traffic. “If we don’t have unrest,” Woods had come to believe, “if we don’t agitate for better things, if there is not a wholesome discontent, we shall not make progress.”

These broad-minded policies had won over some of New York’s most skeptical observers. “Commissioner Woods has nerve,” judged Lincoln Steffens, who had been a leading critic of the police department for the previous twenty years. The veteran journalist had been especially impressed by the triumph at Union Square. “There was no show of force at all, and no abridgment of free speech,” he wrote. “It was an experiment in liberty, and liberty worked.” Walter Lippmann was so enthusiastic about Woods’s success that he quickly redrafted the opening paragraph of Drift and Mastery, his work in progress. “In the early months of 1914,” he wrote, “widespread unemployment gave the anarchists in New York City an unusual opportunity for agitation.” Newspapers and government officers had succumbed to hysteria and violence, but then there was an about-face: “The city administration, acting through a new police commissioner,” ordered an end to repression. “This had a most disconcerting effect on the anarchists. They were suddenly stripped of all the dramatic effect that belongs to a clash with the police … their intellectual situation was as uncomfortable as one of those bad dreams in which you find yourself half-clothed in a public place.”

Woods himself did as much as anyone to promote his own ideas. A onetime newspaperman, he wrote punchy and dramatic essays about his experiences with the police. Lecturing to society audiences, he portrayed himself as a cosmopolite of crime, cracking wise with seamy characters that his audience would have crossed the street to avoid. He titillated listeners with tales of Lefty Louis, Hunchy Williams, and other criminals of his acquaintance, then left them sobbing over the sacrifices and simple wisdom of his patrolmen. Over and over again he spoke of the Union Square demonstration and described how his men had protected antiwar speakers, including Becky Edelsohn, from angry mobs in Lower Manhattan. These parables of toleration soon earned him a reputation as one of the nation’s leading advocates of civil liberties.

In all his speeches, however, he never mentioned another aspect of his practice, the tactics he referred to—when he mentioned them at all—as “graveyard work.” This was no oversight. Arthur Woods believed in clandestine policing with the same conviction he showed for free speech. To him they were two sides of the same strategy. But he had learned through harsh experience that secret practices were best kept private.

IT WAS IN 1900 that the police department had first felt its lack of an effective plainclothes branch. That year, Italian anarchists living in Greenwich Village and New Jersey sent an assassin back to the home country to murder King Umberto I. Learning of the attack, a shocked New York police chief at first denied that the plot could have originated in his jurisdiction. “He had heard nothing of a local group of Anarchists for the past two years,” it was reported. “If such a group did exist he would have known about it.” Once he accepted the fact, however, a second truth became apparent: He was helpless to investigate. In the entire force, there were only a few Italian-speaking detectives. One of them, Giuseppe Petrosino, a brilliant young sergeant who had immigrated from Campania twenty-five years earlier, was immediately assigned to the case.

The city had changed, but the police had not. Officers patrolling the old beats found transformation at every storefront and corner. Kleindeutschland teemed with Russians; Italians pressed the Chinese in Mott Street. “Within a few minutes’ walk is the Hebrew colony of the great East Side. Within half a mile is the German colony to the northwest, while to the west are the colonies of Assyrians, Egyptians, and Arabians.” Eighty-five percent of all residents were either foreign-born or the children of immigrants. “The Irish patrolman,” commented a reporter for McClure’s, “watched curiously over this half million of queer, jabbering foreigners like a child regarding a strange bug.”

More than a million and a half Italians would process through Ellis Island during the next ten years, nearly a third of them settling in Manhattan and Brooklyn. “Generally speaking, they are gentle drudges—honest, faithful, and inoffensive,” Munsey’s magazine assured its readers. “As to their alleged proneness to crimes of violence, there has been much exaggeration.” Compared to the Irish, for instance, they were less disposed to pauperism, drunkenness, or suicide. “In 1904, only one in every twenty-eight thousand Italians in New York was sent to Blackwell’s Island,” reporters noted, and most of these had been charged merely with disorderly conduct.

Lieutenant Giuseppe Petrosino.

If crime existed in the Italian colonies of Mulberry Bend, Williamsburg, and Eastern Harlem, that hardly separated these areas from other densely packed and impoverished districts in the city. But the Italians soon found themselves encumbered with an extraordinary reputation for delinquency. Every trespass in their neighborhoods was attributed to the actions of a mysterious criminal syndicate—the Black Hand. Police officials and newspaper reporters stoked fears over what they dubbed “perhaps the most secret and terrible organization in the world,” and endowed the situation with the appearance of a crisis. “The city is confronted with an Italian problem with which at the present time it seems unable to cope,” the Tribune had complained in 1904. Those same detectives who had been helpless in the anarchist investigation found themselves confounded by the rash of bombings, kidnappings, and blackmail that constituted the Black Hand crime wave. With community leaders calling for protection, and newspapers filled with chilling stories, the police commissioner announced the creation of an Italian squad solely dedicated to infiltrating the mafia. Petrosino took command; under him was every detective in the force who could speak the language. There were nine of them.

For secrecy, Petrosino and his men avoided headquarters, at first operating out of his two-room apartment. But there were so few of them working the same streets day after day that secrecy was impossible. “Every New York detective is more truly a public character than the Mayor is,” a reporter observed. The elected leader of the city “could walk a thousand miles up and down his five boroughs without being recognized by more than a handful of citizens … But let a ‘plainclothes man’ sally forth, and patrolmen will nod to him, streetcar conductors will ask no fare, hallboys will pick him out, janitors will make a sign, bootblacks will look eagerly about for his quarry, politicians will wink patronizingly, barbers will stop in the midst of a shampoo.” When new criminals arrived, old hands taught them straightaway to recognize all the undercover operatives on the force, and Petrosino himself “was probably the most widely known Italian in New York.”

With no hope, then, of operating in secret, they resorted to publicity and “brass band” methods, developing a large network of contacts and sources, working with leaders in the Italian colonies to bolster community resistance against criminals. Over time, Petrosino concluded that secret policing, even done effectively, would never solve the ills that had befallen Little Italy. He coordinated neighborhood vigilance committees and urged settled immigrants to shepherd new arrivals through the process of assimilation. “There is only one thing that can bring about the end of the Black Hand,” Petrosino explained to a reporter from the Times, “and that is enlightenment.”

Lacking this more general approach, the secret branch made hundreds of minor arrests but did little to address the root causes of crime. Most of the time, the suspects they did manage to detain were released by the magistrates. With no reason to believe that the police could protect them, witnesses were hard to come by in Black Hand prosecutions. After two years, the squad could claim few successes. “The number of crimes attributed to the Black Hand society … has grown,” the Tribune reported. “In the more serious cases, such as murders and fires, there have been no convictions.” The initial enthusiasm for the unit dissipated; its members were ridiculed by the rest of the Detective Bureau. By 1906, only “a dejected pretense of an Italian squad was in existence.”

But that year a new police commissioner arrived. Theodore Bingham was an ex-army engineer with a wooden leg and a determination “to put the town under martial law.” Enemies denounced him as “autocratic and severe,” while even his friends conceded that “there is a decisive and a soldierly directness about Gen. Bingham which has often been mistaken for abruptness or brusqueness.” An amateur genealogist, he boasted of ancestors who had come from England in the seventeenth century to help settle the village of Norwich, Connecticut. He had little affection for anyone whose forebears had arrived much later than that—which included nearly every immigrant in his constituency. “Predatory criminals of all nations” had infiltrated the city, he wrote, “the Armenian Hunchakist, the Neapolitan Camorra, the Sicilian Mafia, the Chinese Tongs … the scum of the earth.” His aversion to Hebrews would make him a loathed figure in the Jewish community, but this was as nothing compared to the revulsion he felt for “the Italian malefactor,” who Bingham asserted was “by far the greater menace to law and order.”

Having alienated 90 percent of the electorate, Bingham proceeded to lose the sympathy of subordinates by incessantly harping on the deficiencies of his department. “I have done all in my power with the force at my command,” he complained, demanding funds for more than a thousand new recruits. In a memorandum to the mayor, he proposed dissolving the existing detective branch and starting over with a new secret service modeled on the Italian Carabinieri, the Sûreté of Paris, or England’s Special Branch. “The crowning absurdity of the entire tragic situation in New York lies in the circumstance that the Police Department is without a secret service,” he insisted in a notorious article in the North American Review. “In the one city in the world where the police problem is complicated by an admixture of the criminals of all races, the Department is deprived of an indispensable arm of the service.”

Annoyed by the commissioner’s griping, the Tammany mayor at the time ignored all of his pleas except for the least expensive one. Bingham was granted the right to assign a new assistant to his staff. In June 1907, he created the position of Fourth Deputy Commissioner and chose Arthur Woods to fill it. Not just another underling, Woods took charge of the Detective Bureau. To him would fall the day-to-day responsibility of implementing Bingham’s vision of an American secret service.

Lieutenant Petrosino also hoped to contribute to the new commissioner’s efforts. He presented Bingham with a far-ranging report, offering his multifaceted plan to curb the lawlessness of the Italian colonies. While it did include repressive measures, such as mandating deportation for anyone convicted of a crime, many of his suggestions were broadly ameliorative: educating the Italian community about the American legal system, reducing population density in the tenements, and controlling the sale of explosives. “It’s our own stupid laws,” Petrosino believed, “that have allowed them to organize.”

But Bingham had no interest in anything for the Italian colonies but secret policing, or, as he described it, “rigorous punitive supervision.” Petrosino’s advice was brushed aside; he was ordered to focus on clandestine work alone. Moved to a larger—though still inadequate—office on Elm Street, he was granted more resources: Every Italian-speaking patrolman in all five boroughs was reassigned to his supervision, until the branch contained about eighty men. Knowing that the unit could never expand enough to keep pace with the increasing rates of crime, he nevertheless had no choice but to grind on. “Petrosino and his men have been worked beyond their endurance,” a Times reporter wrote. “Some of them sleep on the tables in the dingy little room which is their headquarters. Petrosino himself has seen little of his home and family for six months.” Still, results from the added labor remained elusive.

Bingham found yet another justification for why the city needed a real undercover force in 1908, with the botched attempt of a Russian anarchist to assassinate a phalanx of policemen in Union Square. “Americans have never been brought to consider anarchism seriously,” the commissioner grumbled. “There is always the possibility of some crack-brained fanatic being influenced by the anarchist … to a desperate deed.” He estimated that at least a thousand radicals currently resided in the city, and to counter their plans he again demanded $100,000 and the creation of a secret service on the French or Italian model. Critics pointed out that despite their renowned clandestine organizations, these nations had been subject to a litany of assassinations during the previous decades. “Secret police have not stopped ‘Anarchist’ outrages in the Continent,” noted David Graham Phillips, a famed muckraker. “Why should they here?” But Bingham was unmovable in his determination to infiltrate the city’s “gangs of Italian criminals and their anarchist accomplices.”

Another year of frustrating Tammany obstructions would pass before he finally got the chance to put his theories to a street test. Then, in February 1909, a Times article conveyed the startling news that “police commissioner Bingham has a secret service of his own at last.” The mood was jubilant at headquarters. “I have money and plenty of it,” the commissioner crowed, “and it didn’t come from the city.” Coy about specifics, he let it be known that he had obtained most of the financing from bankers and merchants in the Italian community, people who had been subjected to blackmail and other Black Hand predations and believed plainclothes police were the solution. But not all the money had come from Little Italy; there was a mystery benefactor, “said to be the head of one of the great industries of this country, whose great wealth has made him the target for all sorts of letters.” Most assumed this meant John D. Rockefeller.

The money went to hire a score of special officers, including men who had once served in the Italian Carabinieri and who would now act as a paid private investigative force under the supervision of the police department, answerable only to Petrosino and the commissioners. Hoping to deport anyone from New York who had a criminal record in Italy, Woods traveled to Washington, D.C., to seek President Roosevelt’s assistance in negotiating a repatriations treaty with the Italian government. As for Petrosino, nobody had seen him. Pressed on the lieutenant’s whereabouts, Bingham coyly replied, “Why, he may be on the ocean, bound for Europe, for all I know.” As it turned out, he was. And the commissioner’s slip was an unpardonable indiscretion. Petrosino had traveled to Sicily to gather the criminal files needed to begin deportation proceedings. Word of his arrival spread. Only two weeks after Bingham announced the creation of his new secret service, Petrosino was shot dead, with four bullets in his back, on the streets of Palermo.

The experiment of using privately financed special agents faltered after Petrosino’s death. Sensing another setback, Arthur Woods wrote an article in McClure’s to argue Bingham’s position that America was vulnerable to the plots of criminals and anarchists. “Here the police are local,” Woods noted. “We have no national police force.” The absence of a federal investigative bureau put more emphasis on the city’s efforts. All resources should be in play. If the Italian squad had failed, he believed, it was only because it had not been ambitious enough. Regular detectives could never succeed on their own, but “if they could be supplemented by a dozen or twenty men,” Woods argued, “working always under cover, never appearing in court or at headquarters, there would be fewer mysterious stories in the newspapers, and the jails would be more full of swarthy, low-browed convicts.”

But neither Bingham nor Woods would be in office long enough to implement these plans. Fittingly, it was their commitment to surveillance that resulted in their downfall.

For the previous fifty years or so, every person arrested in New York had been photographed, and their portrait added to the Rogues’ Gallery at police headquarters. Over time, the collection had expanded to encompass more than thirteen thousand images. It had grown so unwieldy that suspects often had to be released because investigators could not sort through the mess and locate the proper picture that would have incriminated them. Arthur Woods’s first assignment as deputy commissioner had been to reorganize the entire system.

Among the thousands of other photographs, there appeared the face of George Duffy, a milkman from Brooklyn, who two years earlier had been seized as “a suspicious person,” held overnight, and then released without charges. It had been a simple case of wrongful detainment, but because he was in the Rogues’ Gallery, police detectives now recognized him on sight, and his life became a nightmare of constant harassment and arrests. Duffy’s father complained to New York State Supreme Court justice William Gaynor, an inveterate critic of policemen, who agitated to have the picture removed from the collection at headquarters. When Bingham refused, the judge penned a public letter censuring the police commissioner. “He is possessed of the most dangerous and destructive delusion that officials can entertain in a free government,” the note concluded, “namely, that he is under no legal restraint whatever, but may do as he wills, instead of only what the law permits.”

Rather than admit their mistake, Bingham and Woods attempted to convince the public that Duffy was, in fact, what they said he was: a criminal whose picture belonged in the gallery. While reporters interviewed his parents, employers, and even former teachers—all of whom confirmed the milkman’s good character—the police attempted to link him to prostitution and fraud, slandering him as a “degenerate.” The cover-up drifted over toward intimidation; Gaynor, and Bingham’s other critics, believed that they were being followed by detectives.

The commissioner had made too many enemies to survive the Duffy Boy scandal. On July 1, 1909, Bingham was dismissed. His replacement dismantled the secret service squad two weeks later, and the men of the Italian branch were put back on common patrol duty. Judge Gaynor used the popularity he had accrued as Duffy’s defender to mount a successful campaign for the mayoralty. For Arthur Woods, who resigned in solidarity with his chief, the warning was clear. Secret policing had to be conducted discreetly. He would write no more articles praising the idea of clandestine surveillance. Henceforth the graveyard work would be conducted out of sight, where it belonged.

* * *

JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR., glanced up from his four-by-six-inch note card and scanned the audience in the Pocantico Hills Lyceum, just down the road from his estate. The small stone building served the village as library, theater, and dance hall. On Sunday evening, April 19, the folding chairs were arranged in neat rows and the Lyceum had been transformed into a church. Junior was presenting the vespers talk on the subject of “workaday religion.” Amongst the gathering, he recognized Abby and the children, neighbors, employees: friendly, familiar faces all.

“Workaday religion,” he continued, “is not primarily to die by but to live by. It is not primarily for old age but for youth.” He looked back at his notes.

Workaday Religion

1. its uses

a. not primarily to die by but to live by.

b. ″ ″ for old age ″ for youth.

2. everyone needs it

A Christian but not doing anything about it.

3. they need it now

What if all Pocantico had this religion.

After propounding these ideas, he offered a sort of test his listeners could use to tell whether they possessed the faith that he had been talking about. There was a passage in the Book of Matthew describing Judgment Day, when the Lord would divide the charitable from the selfish and reveal that every compassionate act on earth had been a mercy to God. This was the origin of the Golden Rule, the foundation of his beliefs. “Verily I say unto you,” quoted Junior at the conclusion of his speech, “In as much as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, you have done it unto me.”

The next morning—Monday, April 20—was cold and blustery in the Colorado coalfields. Linens twisted and wracked on the clotheslines of the Ludlow encampment, the temporary headquarters for the United Mine Workers in its campaign against Colorado Fuel & Iron. Not far from the border with New Mexico, and fifteen miles from the militia barracks in Trinidad, Ludlow itself was little more than a railroad depot flanked by a huddle of houses. The strikers’ tents, imported from a previous labor conflict in West Virginia, were laid out in not-quite-military precision across a flat patch of prairie.

More than a thousand people had lived there since the previous September. Fitted out with wooden walls, plank floors, and coal stoves, the bivouacs were grim, if scarcely less comfortable than the company-owned shacks the workers had been forced to leave when the lockout had commenced. After eight months of blizzards and rainstorms, the canvas had grayed and worn out; but the inhabitants had managed to add some personal effects, a few sticks of furniture, silverware and china, some photographs. Frequent gunfire had inspired many families to fortify; some had dug pits under the floorboards, and beneath one structure there was a large bunker meant to serve as a maternity ward for the pregnant women of the settlement.

Those precautions now seemed excessive. The violence that had marked the earliest phases of the conflict had dissipated; months of nearly constant warfare had been replaced by a lull. No one had been killed on either side for more than a month. “On the whole, the strike, we believe, is wearing itself out,” an optimistic L. M. Bowers had written to Junior on April 18, “though we are likely to be assaulted here and there by gangs of the vicious element that are always hanging around the coal-mining camps.”

Most of the militiamen had withdrawn, leaving only two companies to protect replacement workers and patrol the mine operators’ property. Though their numbers had been reduced, the troops who remained were among the most belligerent. Their ranks included former mine guards, soldiers of fortune, ex-convicts, and deserters from the regular army. These men, whom Bowers especially praised, made no pretense of impartiality. Other units had mingled freely with the people of Ludlow, but these combatants were on the side of the operators; they unequivocally viewed the miners as “the enemy.”

Early on April 20, a detachment of soldiers visited Ludlow on the pretext of asking about a man whose wife believed he was being held against his will in the camp. The union leader informed them that the woman’s husband had left the previous day, but the soldiers refused to accept his answer. Using this excuse as a way to aggravate tensions, the troopers gave an ultimatum: Produce the missing person by noon, or submit to a search of the settlement. The militia then returned to their headquarters and geared up for combat, marshaling forces and positioning a machine gun—which, like the miners’ tents, had also been imported from a previous strike—on a high spot of ground commanding the level plain where the tents stood.

Sensing an attack, the residents of Ludlow hustled their families into the nearby hills. “The prairie was covered with human beings running in all directions like ants,” one of the miners’ wives recalled. “We all ran as we were, some with babies on their backs, in whatever clothes we were wearing.” The union men snatched up hidden rifles and flung themselves into defensive trenches outside the camp. The two sides began shooting at just about the same moment. Refugees were still in flight when the first bullets fired; those who had not been quick enough to flee pried open their floorboards and scrambled into the pits beneath the tents.

Gunfire continued for several hours, with casualties on both sides. By the early afternoon, though, militia reinforcements had arrived, bringing with them an automobile fitted out with a second machine gun and seven thousand rounds of ammunition. “Go in and clean out the colony,” their commander told them, “drive everyone out and burn the colony.” When these soldiers attacked, the defense cracked; “both machine guns,” wrote John Reed, “pounded stab-stab-stab full on the tents.” Inside, the bullets shattered mirrors and splintered furniture. By sunset resistance had been subdued, and the soldiers roamed unhindered, ransacking the settlement. The “men had passed out of their officer’s control,” investigators would later conclude, “had ceased to be an army, and had become a mob.” They looted “whatever appealed to their fancy of the moment … clothes, bedding, articles of jewelry, bicycles, tools and utensils,” and then began to systematically burn the tents, dousing the canvas with oil before tossing on the matches.

Most of the remaining families were soon smoked out: Unearthly, screaming figures appeared suddenly from their subterranean pits and ran from the scene, refusing any offer of assistance by the soldiers. But the women and children who had chosen to conceal themselves in the maternity bunker decided to stay, even after the tent above them began to crunch with flames. They coughed in the smoke, and their prayers came shorter as the fire drew out the oxygen from their hiding place; the floorboards above them were too hot to touch.

At dawn the next day, soldiers were still passing torches round the camp, firing the rest of the tents, so that, barring a few camp stoves and iron bedsteads, nothing of Ludlow would be left standing. The sun was well up before anyone discovered the charred bodies of two women and eleven children who had been suffocated in the pit.

Ruins of the Ludlow Colony.

L. M. BOWERS WIRED his summary of the battle to Junior while the smoke still hung over the burnt tents. Describing AN UNPROVOKED ATTACK UPON SMALL FORCE OF MILITIA YESTERDAY BY 200 STRIKERS, he suggested that the Rockefellers tell the news to some FRIENDLY PAPERS, in order to begin influencing the press coverage. But this time it was Bowers’s telegram that arrived too late. NEW YORK PAPERS HAVE PUBLISHED FULL DETAILS, a distressed Junior snapped back. TO-DAY’S NEWS IS APPEARING ON TICKER. WE PROFOUNDLY REGRET THIS FURTHER OUTBREAK OF LAWLESSNESS WITH ACCOMPANYING LOSS OF LIFE.

Having tried desperately to secure his personal integrity from the discord inherent in economic practices, Junior now faced his worst fears. He would be faulted for what had just occurred. The Rockefeller name would again be condemned to vicious hatred. Hoping somehow to prevent this, he grasped at any chance to clear himself of blame. Perhaps the recent battle had not directly involved the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company; there were other operators in the region, after all. On April 23, he demanded a clarification on this point from Bowers:

HAVE ANY OF THE DISTURBANCES REPORTED IN YOUR TELEGRAM OF YESTERDAY OR THOSE REPORTED IN TO-DAY’S PAPERS OCCURRED IN CONNECTION WITH MINES OWNED BY OR WITH FORMER OR PRESENT EMPLOYEES OF THE FUEL COMPANY? PLEASE ANSWER.

His subordinate’s response evaded the question, asserting that NONE OF THE THREE MINE TOPS DESTROYED OWNED BY ANYONE CONNECTED WITH THIS COMPANY NOW OR FORMERLY. But Junior had not asked about “mine tops.” What he needed to know was whether the women and children in the pit had been his responsibility. He immediately wired another cable:

REFERRING TO MY EARLIER TELEGRAM, WERE ANY OF THE PEOPLE KILLED OR INJURED OR ANY OF THOSE TAKING PART IN THE DISTURBANCES OF THE LAST TWO OR THREE DAYS PRESENT OR FORMER EMPLOYEES OF THE FUEL COMPANY? PLEASE WIRE FULL REPORTS DAILY

Bowers’s reply—NONE OF OUR EMPLOYEES INJURED NOR PROPERTY DESTROYED YET—was either willfully or wistfully inaccurate. Concerned by Rockefeller’s preoccupation with the victims, Bowers tried to recall his attention to workaday matters. MUCH LESS DISTURBANCE TO-DAY THAN WAS ANTICIPATED, he wrote on April 24. TRAIN WITH SOLDIERS ON WAY TO STRIKE DISTRICT IS CAUSING ANXIETY. FEARING DYNAMITING OR OTHER MISCHIEF.

Meanwhile, the censure had already begun. In Mother Earth, Alexander Berkman called for vengeance: “What are the American workingmen going to do? Are they going to palaver, petition and resolutionize? Or will they show that they still have a little manhood in them, that they will defend themselves and their organizations against murder and destruction? This is no time for theorizing, for fine-spun argument and phrases. With machine guns trained upon the strikers, the best answer is—dynamite.”

And Berkman, for once, was not the only recriminatory voice. Even the Times conceded the enormity of what had occurred in the coalfields. “Somebody blundered,” wrote the stunned and anxious editors after catching the first horrific rumors of the bloodletting. “Worse than the order that sent the Light Brigade into the jaws of death, worse in its effect than the Black Hole of Calcutta, was the order that trained the machine guns of the State Militia of Colorado upon the strikers’ camp of Ludlow, burned its tents, and suffocated to death the scores of women and children who had taken refuge in the rifle-pits and trenches.”

Labor radicals, who had for years preached the righteousness of violence against capital, would now see their doctrines justified. Each street-corner agitator who had ever denounced the Rockefellers as murderers would believe that judgment confirmed. Before Ludlow, revolutionists had occasionally attacked with bomb and flame and pistol. And now the government had responded in kind. After “a sovereign State employs such horrible means,” the editors asked, “what may not be expected from the anarchy that ensues?”