Spring had not arrived with the equinox, and April was proving to be “a dreary period of chill rains and raw winds.” A brilliant Easter, a few teases of sunshine: These did little against the run of pinched and pallid days. Weeks passed without a hint of change, particularly in those districts where no greenery survived to mark the rhythms of nature. “New York’s landscape is red,” observed a tenant on Thirty-fourth Street, “brick red or brownstone red … Manhattan spring is red.” A month of this had sapped the city’s patience. “When after a long and bitter winter,” an editor at the World complained, “the calendar promises grateful relief, and the elements deliberately proceed to falsify the season’s prospects, a harassed people have a moral right to rebel.”

When renewal began to appear, it came gradually and in private moments: “with a bit of slanting sunlight,” the Evening Post suggested, or “the glimpse of some flower on a windy street-corner.” Warmth interspersed among chill days as “little by little, the sun was getting the better of his enemies.” The starlings were singing again near Riverside Drive. On Broadway, “fur coats alternated with gray flannel suits,” and winter hats gave way to derbies. The tune of hand organs brought dancing children to the East Side streets. “It was that time of the year when all the world belongs to poets,” Upton Sinclair had written in one of his early novels. “There are two weeks, the ones that usher in the May, that bear the prize of all the year for glory.”

The hazel was thriving at the uptown end of Central Park, near 110th Street, where Sinclair and his second wife had recently taken an apartment at the extortionate rate of ten dollars a week. Eight years had passed since the publication of The Jungle, and the dividends from that success were gone. His writings had brought stingier advances—and critical praise, too, had diminished. A review of his latest novel in McClure’s had ended by reflecting: “You may search your soul for a tenable reason why Mr. Sinclair thrust this impossible brew upon the public.”

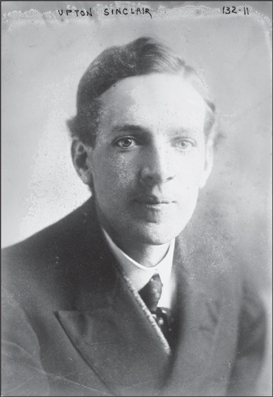

He was thirty-five years old, bookish and slight, with “large, earnest eyes” and an “almost girlish face.” Rarely wasting a thought on his unkempt hair or clothes, he was modest in manner, “by instinct shy.” He had no fondness for “the turmoil of the crowd,” and yet he always ended up at the center of controversy. He possessed an empathy and anger that overruled his reticence, compelling him out into the forum whenever injustice appeared. “I clench my hands,” he wrote, “and bite my lips together and turn on the fierce and haughty and powerful men with a yell of rage.”

His zealous interventions were a constant exasperation for his allies. To Walter Lippmann, who had known him since their days in the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, these passionate furies had become embarrassing. “Mr. Upton Sinclair’s intentions are so good,” the cynical, aloof Lippmann had written, “his earnestness so grim, and his self-analysis so humorless” that he “is forever the dupe of his own sincerity.” Victor Berger, the Socialist congressman from Wisconsin, was even less charitable. “Sinclair is simply an ass,” he confided to reporters. “He is not recognized by any Socialists that I know of as their representative.” The writer’s antics were a godsend to reporters, who made him “the butt of countless jokes and the target of much ridicule.” Everything he did, they turned against him; “the fact that Upton is for it makes one loathe it,” sneered a columnist for the Chicago Tribune. Nor had he helped his own good name with a quest for perfect health that had embraced prolonged fasting, frequent sanitarium stays, and a brief experiment with the “monkey and squirrel diet.”

Upton Sinclair.

In April 1914, Sinclair celebrated the one-year anniversary of his second marriage, to Mary Craig Kimbrough—or Craig—an aspiring writer who came from an aristocratic Mississippi family. They had met during one of his sanitarium stays, and she had already spent much of their married life restraining her husband’s crusades. Then, on April 27, he attended a meeting of socialists at Carnegie Hall, where Laura Cannon—wife of the president of the Western Federation of Miners—told the story of the Ludlow Massacre. Sinclair had been following the events in Colorado, but he had not yet heard the pathos of the details. Along with three thousand other members in the audience, he jeered and hissed at every mention of “Rockefeller.”

Sinclair’s novels featured figurative characters, each representing broad social categories. Workers were innocent and often heroic, bosses were cynical or brutal; whatever their personal qualities, individuals stood for large ideas. He thought of John D. Junior, in his office above Broadway, blithely condemning hundreds of families to starvation and death. He recalled that the man professed himself a Christian, and even led a Bible class to teach morality to others. Here was a character worth confronting. Picturing this parasite, this hypocrite, Sinclair had the nearly uncontrollable desire “to wait for Mr. Rockefeller at the entrance of his office and publicly horsewhip him.”

Back home in the apartment, at 50 110th Street, near Madison Avenue, Sinclair declared that that night’s supper would be his last: Henceforth, he would fast in solidarity with the strikers. Pacing and ranting, he flatly refused to come to bed. His wife tried to calm his excitement, but he was already planning his next outrages. Visions formed in his imagination: a picket line in front of the Standard Oil Building, grave and picturesque protesters mourning the deaths in Colorado. Junior would become a pariah, abandoned by friends, unwelcome in society. “Now, we don’t need to kill Rockefeller,” he decided, “no, not even if the worst thing his worst enemy might think of him should be true. Giving him the ‘social chill’ will count more than death would.”

“They will surely arrest you,” Craig observed.

“Of course they will; and that is what is needed.”

She reminded him of the state of their bank account: There were no funds left to pay the fines. “Someone will put up the money,” he reassured her. Finally, she offered a compromise. Rather than picketing, they should go together and pay a visit to Rockefeller in person. If he refused to see them privately, then they could demonstrate in public. Grudgingly agreeing, Sinclair finally permitted himself some sleep.

The next morning, husband and wife appeared at the entrance to 26 Broadway, the “severe but imposing” fifteen-story skyscraper that was “known in every part of this broad world as the headquarters of the Standard Oil.” Inside, they handed the secretary a note, informing Mr. Rockefeller that Upton Sinclair had arrived to see him. The secretary vanished briefly and returned, asking them to come back in an hour for a reply. They did, only to be told there would be no meeting. Sinclair presented a second note, prepared in advance. “Do not turn us away,” it read, “but let us tell you what we know. You will find us quiet and courteous people. We ask nothing but a friendly talk with you.”

The clerk returned again, with Junior’s final word: “no answer.”

The next morning, April 29, Sinclair returned to the Standard Oil Building. He and the four women who had agreed to join him as mourners wrapped black crepe bands around their right arms. Then they linked hands and began solemnly to pace the thirty feet of sidewalk that stretched before the entrance to 26 Broadway. A small crowd gathered to watch. After about five minutes, a clutch of patrolmen came over to suggest they take their little walk somewhere else. They refused. A police officer grabbed Sinclair by the arm and began shoving him forward.

“Please behave like a gentleman,” Sinclair hissed in his ear. “I have no idea but to go with you.”

At the precinct house, he told the desk sergeant the story of the Ludlow Massacre, then he repeated the narrative again to the magistrate who arraigned him on charges of disturbing the peace. Having been ordered to return to court the next day for sentencing, Sinclair hurried back to Broadway, where he found his wife in command of a new group of mourners. All afternoon, the protest continued to grow. Alexander Berkman, who had been leading his own rally with Becky Edelsohn near City Hall, came to take his turn among the pickets. Volunteers kept arriving, and confidence was high. That day, Sinclair somehow found funds to rent an office in a nearby building. He had telephones delivered, and was about to order stationery when he realized the movement needed a name. “We had to fight it out for free speech,” said Leonard Abbott, a leading anarchist from the Ferrer Center. “Now we will fight it out for free silence.” The letterhead would read, FREE SILENCE LEAGUE.

In a light suit, with a black mourning band on his arm, Upton Sinclair paraded solemnly in front of the Standard Oil Building on Lower Broadway.

AS PROTEST PLANS coalesced in New York City, the slaughter climaxed in the coalfields. In the week following the assault on Ludlow, avenging miners had counterattacked, and dozens more combatants and innocents had been killed. With the state militia on the defensive, L. M. Bowers and Junior now demanded that Woodrow Wilson send federal troops to protect their property in the mines. Hesitant to let Colorado Fuel & Iron executives employ U.S. soldiers for their own ends, the president had tried to compromise. If Rockefeller would submit to arbitration, or otherwise demonstrate his goodwill in settling the strike, he offered, then Washington would consider sending military assistance.

To conduct negotiations, Wilson dispatched Representative Martin Foster, the leader of the committee that had called Rockefeller to testify earlier in the month. For three hours on April 27 the two sides discussed possibilities, but the bloodshed had done nothing to alter Junior’s position. He still refused to budge on the only substantive issue—the miners’ right to unionize—and the congressman departed in frustration. “The attitude of the Rockefellers,” he told reporters afterward, “was little short of defiance, not only of the Government, but of civilization itself.” In the end, Wilson conceded to Rockefeller’s demands anyway. He had no choice. Violence had spread more than 150 miles north, nearly reaching Denver, and civil unrest was tending toward civil war. On April 30, both sides watched with relief as U.S. troops detrained at Trinidad, fifteen miles south of the ruined Ludlow tent colony. Miners and militiamen alike turned over their firearms to the federals. The truce did nothing, however, to end the strike—nor did it placate the Rockefellers’ critics.

IT WAS SOPPY and bleak in New York on Thursday, April 30, a day of chastisement for the Rockefellers. Upton Sinclair left his apartment before nine A.M. and traveled to court for his sentencing. Having eaten only an orange and some ice cream since Monday night, he was “working under high nervous tension.” In front of the magistrate downtown, he rambled and protested so much that the court had to forbid him from launching into any further orations.

“I had a moral purpose when I went to 26 Broadway,” explained Sinclair. “I wanted to bring home to Mr. Rockefeller the feeling that he is responsible for the murders in Colorado.”

“You are making a speech,” chided the judge.

“This is a serious crisis of my life. I am facing a physical breakdown.”

He so disrupted things that the proceeding, which usually took a few minutes, lasted nearly two hours. For disorderly conduct he was given the choice between paying a three-dollar fine or spending three nights in a cell. Not believing they would dare send him there, he chose prison.

“I say to you that I will go to jail,” raved the defendant, “and lie there till I am carried out dead, if need be!”

“All right,” replied the exasperated judge, “if you like.” And, before he quite realized what was happening, Upton Sinclair was being escorted across the Bridge of Sighs, the notorious passageway leading from the courthouse to the Tombs.

With Sinclair incarcerated, the leadership of the protests fell to Leonard Abbott, who served as a link between moderates and anarchists. He spent Thursday morning in the newly acquired office, a converted bedroom up four flights of shaky stairs. His assistants—the students of the Modern School at the Ferrer Center—scampered around performing chores. On the wall, a warning had been posted:

IF YOU WANT TO BRAWL OR FIGHT, GO TO COLORADO, BUT DON’T HURT OUR MOVEMENT BY TRYING IT HERE. WE WANT ONLY MEN WHO WILL PLEDGE THEMSELVES TO SPEAK TO NO ONE AND GO QUIETLY WITH THE POLICE IF ARRESTED.

He told newspapermen that their readers would be amazed if they could hear the names of the prominent citizens who had telephoned during the day to offer donations and support to the Free Silence League. The effort to “send the social chill” to Rockefeller Junior appeared to have the backing of everyone of importance in New York. Even the police department had agreed to give the radicals at least its tacit support. Abbott had spent part of the morning at headquarters talking to Commissioner Woods, who had authorized him to publicize the government’s position: “The city administration considers this a period of intense public feeling, due to the killing of men, women, and children in Colorado. It is the intention of the administration in this crisis to permit the fullest possible play of public emotion through free speech, free assemblage, and free passage through the streets of all persons not engaging in organized parades.”

“So long as we only wear crepe on our arms and do not display banners,” Abbott elaborated, “we may walk up and down in front of 26 Broadway as long as we want to.”

Around midday, however, a group of protesters that refused to bind themselves by rules of any kind were beginning their own demonstration. At noon, the anarchists harangued a sodden, angry crowd at their usual setting, the statue of Benjamin Franklin near City Hall. Berkman and Becky ceded the rostrum to Marie Ganz—an East Side anarchist whom the press had dubbed “Sweet Marie”—who stood on a ledge inciting the audience.

“I haven’t come here to talk about the flag or Mexico,” she began. “I’m going to lead a delegation against John D. Rockefeller, Jr. I want you to come along and wipe him off the face of the earth. I want you to show him that he’s got to take action in the Colorado strike … Follow me!” With a shout, she leapt down to the sidewalk, and, with Berkman and Becky at the lead, began to march down Park Row toward Broadway. Hundreds of rain-soaked demonstrators fell in behind them; scores more joined as they proceeded. With a thousand followers, the anarchists dashed down to Standard Oil headquarters, where the silent mourners were still pacing the sidewalk.

Crowds swarmed the front of the Standard Oil Building each day.

As the police rushed toward Berkman, Ganz slipped through the line of pickets and darted into the building. With a cursed threat, she ordered the elevator operator to take her to the top floor. Bursting in on the startled employees at the innermost sanctum of the corporation, she demanded to see John D. Rockefeller, Jr. He wasn’t in, a nervous secretary stuttered. “Tell Rockefeller,” screamed Sweet Marie, within the echoing walls of the office, “that I come on behalf of the working people, and that if he doesn’t stop the murders in Colorado … I’ll shoot him down like a dog.” And before anyone thought to stop her, she turned and fled back into the elevator.

Down on the street, Berkman and Becky had found a raised platform, and they were hollering protests at a throng of angry clerks and messenger boys. Shards of wood, paper bags, and sand flew at their heads as the police struggled to hold off the mob. Becky, who had just been released from jail for her disorderly conduct arrest from the previous week, was firing up the audience in her indomitable manner. “A crowd of two thousand gathered, jeering and yelling at her,” a reporter wrote. “Twice the crowd surged forward and swept her and her friends off their perch, but they fought their way back, their voices breaking shrilly through the roar.” Finally, using a cordon of officers as a barrier, the anarchists were able to escape down into the Bowling Green subway station.

“Sweet Marie” Ganz.

That evening, reporters visited Upton Sinclair in prison. He paced his small cell on the lowest, most fetid tier of the institution. Finally, he rested on the edge of the narrow cot. “I guess I can sit down,” he said, uncertainly. “The keeper assures me this cell is sterilized.” He had once spent a night in a Delaware workhouse, jailed for playing tennis on a Sunday, but the rancid and filthy Tombs presented a different degree of penance. The keepers had been by with supper, a bowl of stew with some potatoes and bread. “I took one look at it,” Sinclair told the newsmen. “It didn’t interest me.”

He had been too listless to write much that day, scratching out only two lines of a poem. He languidly watched a slant of sunlight falling across the floor and pulled his overcoat around his thin shoulders. Outside, the rainy morning had cleared into a fine, temperate evening. “Do you know that you have the queerest feeling when you’re locked up?” he said, at last. “Gee! But it’s awful.” Only when his visitors described the riotous antics of Berkman and the anarchists did he recover some of his lost energy. “Oh, dear me,” he exclaimed, “these fools! They kill the whole business.” As the reporters started filing out, Sinclair roused himself for one more blast. “I hope you will give this message to John D. Rockefeller, Jr.,” he called after them. “Tell him I hope he enjoys his meals enough for both of us while I am languishing in jail.”

Night was falling in midtown when the ruckus out on Fifty-fourth Street brought Abby Rockefeller, Junior’s wife, to her window. The chauffeurs at the University Club, across the way, were being more than usually boisterous. She peered out onto the sidewalk in front of her mansion and saw a group of men marching back and forth before her door. Black crepe ribbons circled their arms, and they wore pins on their lapels that read THOU SHALT NOT KILL. The mourners had come uptown. Reaching for the telephone, she called Arthur Woods and asked that he send over some protection for her and the children.

When the police hurried over from the Sixty-seventh Street station, they found half a dozen or so I.W.W. men pacing, silent and grim, while onlookers jeered and women taunted them from passing automobiles. Arthur Caron tramped in the lead, his face jaundiced and swollen from the beating he had received at Union Square three weeks earlier.

“What do you want in this neighborhood?” the detective asked him. “Move along.”

“I’m here to walk up and down,” Caron replied, without breaking his pace. “And I won’t move on at all.” More police arrived, until the cops outnumbered the protesters. With the orders from headquarters urging restraint, there was nothing they could do. And so Thursday, April 30, ended with Arthur Caron pursuing his lonely demonstration, east and west along the row, scrutinized by the butlers and servants in the mansions.

“JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR., had yesterday the busiest day he has experienced since the outbreak of the Colorado strike,” declared the Tribune the following morning. “He left a trail of riots, threats and arrests wherever he went.” The next day, which was the first of May—the international workers’ holiday—saw even greater demonstrations: protesters in the public squares, pickets at 26 Broadway, mourners on Fifty-fourth Street, disruptors in Calvary Church, where Junior sometimes led his Bible class. Diffuse anger from months of agitations now converged on one man. Banners in the labor parades accused him of being a “multi-murderer.” Berkman decried him as a coward with a “guilty conscience.” From the West, the president of the United Mine Workers observed that more Americans had been killed in Colorado than in Mexico. “As to John D. Rockefeller, Jr.,” he continued, “his life, in spite of his riches, is empty.”

Attacks from professed enemies he could withstand, but condemnation was spreading far beyond the usual coterie of radicals. Acquaintances and colleagues spoke out against him. Mayor Mitchel’s administration, which he had done so much to encourage, now acquiesced to his tormenters. Pastors in Manhattan took “Rockefeller’s War” as their text; in Brooklyn, a minister “denounced the outrages against the miners.” Newspapers reveled in his mounting unpopularity. “The suspicion is beginning to grow very strongly,” an editor at the Herald surmised, “that the leaders of the strikers rely on the name of Mr. Rockefeller to win their struggle for them.”

Throughout the week, demonstrators haunted his home and office. They terrorized his secretary, his pastor, and even his wife. But none, so far, had seen Junior himself. His movements, and the condition of his nerves, became the subject of widely divergent speculation. Sinclair had heard rumors that Rockefeller was sneaking in and out of 26 Broadway through a back door. The family claimed he was bedridden with bronchitis. Certain sources insisted that the “social chill” had not affected him; according to others, he was “seriously troubled by the agitation at his office and elsewhere by sympathizers with the Colorado strikers.”

In fact, anxious and wounded, Junior had avoided the office all week. On May 1, around noon, he was spotted arriving at Tarrytown, where he spoke briefly with his father, and then retired to his quarters. The next morning, his wife and children joined him behind the walls of the Pocantico Hills estate. Detectives from the William J. Burns agency had been hired to provide extra security; they patrolled the family’s miles of private roads and guarded the gates, accosting anyone who approached. Senior continued playing his habitual round of golf each day, but now he was accompanied at all times by two bodyguards, who “followed him around the course and kept a sharp outlook for strangers.”

Junior found himself housebound and helpless, reduced to scanning the newspapers each morning for signs of approval—and finding little of it. “He has been much affected by the things said and printed concerning him,” his secretary admitted. Junior himself confessed that “the last two weeks have been trying ones, for no man likes to be blamed and criticized, when he feels that such public censure is unfair and unmerited.” He was mortified to think that anger toward him was inadvertently affecting others. “I profoundly regret to bring so much notoriety and discomfort to the Class and the Church,” he wrote to officials at Calvary Baptist, “and hope that this period of public hysteria may soon subside.” To intimate advisers he admitted the strain he was under. “Those who are closest to us,” he wrote to his pastor, “realize how trying the present situation is, for they know its injustice.”

Junior’s detractors did not understand the conflict he was suffering. In public, for the sake of Colorado Fuel & Iron, he had to maintain a unified front with his subordinates. He could not be seen harboring critics of the company, and therefore he had rebuffed not just Upton Sinclair but official union delegates, congressmen, the secretary of labor, and the president of the United States. His press statements reiterated the testimony he had given to Congress. It was the same official position that had been passed down from management: The company treated its workers generously, most employees had no interest in joining the union, labor agitators were responsible for most of the violence. But Bowers, who had always patronized him, had been lying to him as well, and Junior was catching on.

Privately, Rockefeller attempted to ameliorate the situation in the coalfields. The telegram he had sent to Bowers before the massacre ordering him back to New York had arrived too late. Then, in the immediate aftermath of the assault on Ludlow, he had probed suspiciously at Bowers’s crafty omissions concerning the battle. Now, with hatred pouring in on him, Junior kept seeking for a moral policy. He wanted to accept the government’s offer to arbitrate the strike. Bowers refused. When Rockefeller broached the idea of sending “disinterested men” to serve as mediators, Bowers replied that “such a scheme would be most unwise.” Distraught by what he was reading of the violence, Junior’s thoughts turned to the sufferers. IF IT IS TRUE AS REPORTED IN THE PAPERS THAT ANY OF OUR EMPLOYEES HAVE BEEN INJURED IN THE RECENT DISTURBANCES, he cabled to Colorado, I TRUST THAT YOU HAVE ALREADY TAKEN STEPS TO PROVIDE FULLY FOR THEM AND THEIR FAMILIES. This last telegram was simply ignored.

Bowers had one care: to defeat the strikers. The struggle, for him, had grown beyond an industrial dispute. He believed himself to be the leader of the “conservative, level-headed, patriotic business men of the country” in their crusade against “labor union agitators” and “the political muckraking rabble.” Each gesture toward mediation, every suggestion that reforms were necessary—even an offer to reimburse the victims—was an admission of error that would harm the company’s efforts to vanquish the union. Once the miners had surrendered, then and only then would it be appropriate to assess managerial practices. Until that time, unwavering support was necessary.

Junior might have acted on his growing doubts. He could have admitted his mistakes, confessed to having been misled, and set about redressing the wrongs that had been committed in his name. But he did not. Betraying his own better judgment, he relapsed into nervous tension and wiled away his days petulantly griping about the treatment he was receiving in the press. “To describe this condition as ‘Rockefeller’s war,’” he complained, “as has been done by certain of the sensational newspapers and speakers, is infamous.”

In order to painstakingly—obsessively—follow the coverage, he had all the New York dailies forwarded to his sickbed in Tarrytown. Grateful for compliments, he wrote one editor to thank him for his paper’s “fair and broad-minded” reporting. He congratulated Adolph Ochs, publisher of the Times, for an editorial on labor unions. But he was just as quick to protest against any perceived offense. When the World published a few critical pieces, he was particularly upset. “I tried to get you on the telephone today but was informed that you were away,” Junior wrote Ralph Pulitzer, the publisher, who was an old friend.

I simply wanted to inquire whether the editorials regarding the Colorado situation which appeared in the WORLD of this morning, and one or two previous editorials of a somewhat similar tenor, represent your views and were published with your approval. In view of the pleasant relationship which has existed between us I can only assume that these editorials have been written without reference to you and have escaped your notice, for I cannot believe that … you could have authorized the editorial of this morning.

Pulitzer’s response could not have been what Junior had expected:

I have always felt it my duty to accept responsibility for what appears on the editorial page of “The World”. In view of the pleasant relationship which you mention, I will depart from this principle to the extent of saying that had I written or edited the editorials to which you refer, I would have qualified one statement of principle and would have modified certain expressions which might have been construed to contain personal animus, but with these amendments the editorials would have expressed my own views regarding the Colorado situation.

When he was done examining the newspapers, Junior found comfort in the correspondence arriving daily from friends and strangers across the country. “I wish to tell you how deeply … I sympathize with you in your present position—Be patient,” wrote Andrew Carnegie. A note from Oswald Garrison Villard, publisher of the Evening Post, began, “I hope you will let me say how genuinely I have sympathized with you in the annoyances of these past weeks, and that I admire the dignity and self-restraint with which you have borne yourself.” And then there were the letters from supporters he had never met. Most began by apologizing for the intrusion, and many came around to ask for a job. Junior read each one, marking his favorite passages in pencil:

I feel that every man in the Country should write you a short note, congratulating you on the stand you are taking in relation to the strike in Colorado.

Don’t be distressed by those crazy anarchists, etc., who threaten you. Right is right, and will conquer in the end.

What this country needs is a few more Americans like yourself + no more “Americans” of the Sinclair, Edelsohn + Ganz type.

Ahead of all this trouble is the issue of God vs. Anti-God …

I am prepared to assert that all the labor unions in the United States, including the I.W.W., with the exception of the railroad orders, are controlled by the Order of Jesuits …

* * *

Times Square was lonely and forsaken at 7:45 in the morning on May 3, when Arthur Caron met the six anarchists who were to join him for a day’s excursion. The empty theaters and cabarets were shuttered and dark. At the newsstands, the headlines had to do with Colorado and Mexico, or the previous day’s suffrage parades. Stepping down into the station, the little group rode the Broadway subway to its northern terminus in the Bronx. From there, a fifteen-cent trolley fare carried them past the hamlets and farmsteads of Westchester County. At eleven A.M., they disembarked in Tarrytown.

It was Sunday morning, and the sidewalks were packed with families on their way to church. The party asked passersby for directions to the Rockefeller estate, and curious stares followed them as they went. A few blocks took them from the village center onto a quiet country road. The rural setting, and the sunshine, put the leader in a jovial mood; Caron kept up a steady patter of encouragement as they made the two-mile walk. Then the great iron gate to Pocantico Hills emerged into view. The anarchists fell quiet, their eyes following the walls that disappeared from sight in both directions. The estate was enormous, far more imposing than they had imagined.

The great iron gate to Pocantico Hills.

Patrolling automobiles noticed the approaching group before it had reached the gates. Workmen scrambled to lock and chain the entrance. Guards hustled over. They scowled through the iron bars, while others crouched, heavily armed, behind nearby hedges. Junior’s children were called in from their play; pausing for a moment to stare at the protesters, their anxious nurses shooed them on. The radicals did not say a word. In the drive, they paused to tie black crepe to their arms—one woman affixed a card to her hat that read I PROTEST AGAINST THE MURDERS IN COLORADO—and then they started marching with the same “slow, steady tramp” that had resounded across the city.

“We came up here to-day to worry Rockefeller and we have him worried,” Caron told the newspapermen who had come along. “It is a peaceful demonstration, but we intend to keep it up every day. Tomorrow we will have double the number, and we will follow Rockefeller wherever he goes. We have him thinking.” For two hours, they continued their mourners’ march, and then they trudged back into town for an ice cream soda before beginning the long trip home.

The next day, every gate at Pocantico Hills was locked and guarded, and Rockefeller Senior, was laying plans to construct a new main entrance to the estate: It would be “one of the most pretentious in the country,” and utterly unassailable to invaders. Armed men tailed the children in their play. Detectives and workmen patrolled the perimeter, but no I.W.W. assault materialized. Instead, Caron had gone to 26 Broadway to take his turn among the mourners, explaining that he had postponed his next visit to Tarrytown until he could raise a larger corps of volunteers.

Released from the Tombs and eating again, Upton Sinclair was crafting plans of his own. He sent telegrams to leading socialists across the nation, suggesting they add their protests to the New York agitations. THERE ARE BRANCH OFFICES OF STANDARD OIL IN EVERY TOWN, he cabled to party officials in all the major cities. CANNOT YOU OR THE NATIONAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE RECOMMEND THAT MOURNING PICKETS APPEAR BEFORE THESE OFFICES? CANNOT ALL SOCIALIST LOCALS PUT CREPE BEFORE THEIR DOORS? The answer came back: No. “The Socialists here are decidedly tired of this cheap clap-trap of Sinclair’s,” a party secretary informed reporters. “They know it is the quiet work of organizing that counts and never this self-advertising noise. Sinclair’s noise is his own personally organized affair, and we have nothing to do with it.”

Without national support, the ardor drained from the movement. When it rained, the makeshift office became a jumble of drying lines crowded with musty, sagging garments. Hostile passersby shoved mourners to the ground. Businesses complained that the protests were hurting commerce. The granite silence from 26 Broadway persisted, and Junior kept out of sight. “You may judge that it was rather a dull day,” a reporter joked midweek, “the loquacious-lipped and prolific-penned Upton Sinclair didn’t issue a single voluminous statement, and the fair but fiery Marie Ganz didn’t make a solitary murder-threat.” Derision poured in from everywhere. “Why should the authorities of New York interest themselves in trying to prevent Upton Sinclair from his ‘silence’ strike against young Mr. Rockefeller?” asked the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “The more silence there is around Mr. Sinclair’s neighborhood the larger the relief to the rest of the country.”

After a few more days of this, Sinclair decided he was “through with the Free Silence mourning.” It had been intemperate, perhaps rash, to think he could be of service here in New York. He could do more good in Colorado. On Saturday, May 9, he boarded a train for Denver at Pennsylvania Station, leaving his wife and the others to carry on—or not—as they so pleased.

On Sunday, Leonard Abbott disbanded the organization. “The reason there is no more need for the Free Silence League,” one leader explained to the public, “is that the Anti-militarist League, headed by Alexander Berkman, and the I.W.W. forces, headed by Arthur Caron, have taken hold so successfully that we may as well drop out.” But Craig disclosed the true motivation to her friends. She feared the movement was plunging toward bloodshed; not a day passed without at least one visitor appearing at her apartment door, asking her to “give them some job of violence to do.”

The Rockefellers had decided to abstain from Sunday services for a second week in a row, but the pews at Calvary Baptist Church, on West Fifty-seventh Street, were crowded on May 10 with a congregation boasting “the wealthiest and most influential people in the city.” Conspicuous among them were detectives Gildea and Gegan and a squad of plain-clothesmen. As the final notes of the organist’s prelude faded off, the pastor stood at the lectern to announce the text of his sermon: “Samson, the Man of Sunlight, the Man of Tact.” But before he could continue, a middle-aged gentleman in a white suit bounded from his seat and hurried toward the altar. “I am here to speak the truth,” he called out. And then a gang of ushers grabbed him by the arms and began hustling him up the aisle toward the exit. Slipping their grasp, he clung to the back of a pew. They pried at his fingers as he thrashed and kicked. Parishioners shrieked. “I want you to let me speak,” he cried, “so that I can tell you about one member of your congregation who is guilty of the murder of women and children in Colorado.” They pulled him loose, and he stumbled to the floor. As he struggled, his scattered followers rose to their feet and shouted—“Let him speak!” “Shame!”—while the rest of the audience cheered the ushers with cries of “Put him out!”

On the street outside, the disruptor’s white suit was torn by police as he and ten supporters were manhandled into waiting vans. At the Forty-seventh Street station house, he identified himself as Bouck White, a Harvard graduate, author, and founder of the Church of the Social Revolution in Greenwich Village. It was as a fellow man of God that he had risen to challenge the pastor at Calvary Baptist. As a socialist and Christian, he had hoped to redeem the wealthy congregation with a message of poverty and brotherhood. Hundreds of fervent acolytes gathered in the courtroom for his arraignment. When the magistrate released him, pending trial, they threw their hats in the air and hoisted him on their shoulders, rapturous with joy.

For White, the foray into the temple had been a holy mission. “The real God of the Bible,” he explained, “is on the side of the workers and the poor, against the privileged class at the top.” But for most observers, his antics indicated yet another escalation in a months-long series of radical outrages. Allusions to the Haymarket Riot and the Paris Commune began appearing frequently in the press. “Have we not had almost enough of the I.W.W. agitation in this peace loving city of New York?” asked the editors at the Sun. “Is it not time that means were found of stopping malignant provocation to riot?” The Herald offered simple remedies—“A quick application of nightsticks, a proper use of the patrol wagon”—and posed a provocative question: “Is Mr. Mitchel a Mayor or a mouse?”

Arthur Woods had theorized that promoting civil liberties would prevent eruptions of violence: agitators would exhaust themselves with words, instead of pursuing more inflammatory tactics. After a triumphant beginning, this doctrine now appeared more tenuous with every protest action. The invasion of Calvary Church discredited any standing it retained, and Mitchel moved to distance himself from his commissioner.

“Mr. Woods’s ideas on the subject of free speech are known to be extremely liberal,” a reporter explained, “considerably more so than those of the Mayor, who believes that ‘incitement to crime is not free speech.’” For Mitchel, the time for social experimentation was done. “You cannot handle with kid gloves” an occurrence like the attack on Calvary Church, he declared. Radical provocations henceforth would be met with “vigorous methods.” The noonday meetings at the Franklin statue, which had instigated such nuisances over the previous weeks, were banned. Mourning marchers on West Fifty-fourth Street were detained. Marie Ganz was arrested and given sixty days in the Queens County Jail; it took a magistrate only twenty minutes to sentence Bouck White to six months on Blackwell’s Island.

The severity of these measures was partly due to the imminent arrival of the president of the United States. Just a few days after presiding over his daughter’s marriage to the secretary of the treasury, Woodrow Wilson was coming to the city for a memorial service honoring the casualties of the Veracruz invasion. The attention of the entire country would be fixed on the ceremony. For the Mitchel administration, it was a chance to demonstrate the capacities of honest and efficient government. The agitators hoped it would be the perfect occasion to foist their grievances on a national audience. To prevent this, Woods and Schmittberger made elaborate plans for security. By the morning of May 11, the city’s worst troublemakers had been locked away, and New York was as secure as the police department could make it.

THE GATE TO Pier A, in Battery Park, scraped open at nine A.M., and a squad of marines placed the first coffin onto an artillery wagon and draped it with a flag. Spectators clutched their hats to their chests. Warships in the upper bay stood silent; skiffs and tugs in the rivers refrained from the usual bawling and whistles. Sixteen more caskets followed, and when they had assembled, the parade commenced. Mounted policemen led the way, followed by the honored dead and then Wilson, somber and introspective, in an open carriage. Thousands upon thousands of onlookers filled the Broadway sidewalks “from curb to building line.” Up above, they thronged in the windows and crowded the rooftops. Police in dress uniform were stationed every twenty feet. At the Standard Oil Building, the officers lined up shoulder to shoulder. Security agents had observed the demonstrations out front of 26 Broadway for days, and as the president’s carriage approached, “there was a visible increase in the vigilance of his guards in that troubled zone.” Then it was behind them, and there had been no incident.

Business was suspended at the cotton and produce trading floors, the curb market, and the New York Stock Exchange. At the Equitable Building, construction workers paused in their riveting; high up on the steel frame, they gripped the bare girders with one hand and doffed their caps with the other. No one had known beforehand whether or not the crowd would cheer. The answer was now apparent. “The roll of muffled drums,” a reporter wrote, “the soft tread of feet, the gentle tap-tap of the horses’ hoofs, and the rumbling of wheels were the only sounds.” The bell at Trinity Church tolled as the procession neared Wall Street, then St. Paul’s joined in. But the spectators maintained their quiet witness.

Mayor Mitchel, in top hat and formal attire, was waiting on the steps to City Hall as the horses appeared in the plaza. Hundreds of school-children offered a hymn of mourning. The mayor approached a podium, and the singing stopped. “The people of New York pay their solemn respect to these honored dead,” he began. “These men gave their lives not to war, but to the extension of peace. Our mission in Mexico is not to engage in conquest, but to help restore to a neighboring republic the tranquility and order which are the basis of civilization.” When he had finished, Mitchel advanced with long strides forward into the quiet square and set a wreath of orchids on the coffin of a nineteen-year-old seaman from Manhattan.

The choirs took up a new song as the mayor clambered into the president’s carriage. Seated there, he appeared even younger than usual. The military spectacle had him fired with a craving for action and sacrifice, and his excitement made it difficult to maintain the proper dignity. In contrast, Wilson—wearing a pince-nez, and with wispy gray hair protruding beneath his hat—had a haggard look. “The President was silent and very grave,” a reporter observed. “His square jaw was set … and his eyes were misty.” He had toiled through months of personal anguish before ordering the marine expedition to Veracruz, and now he faced the awful results of that decision. With thoughts of death upon him, he congratulated the mayor on his fortunate escape from assassination. Then he relapsed into somber introspection. The leaders of the two largest governments in the United States rode up Centre Street together, past the Tombs, without a word.

The invasion of Veracruz had not lived up to the president’s hopes. Never imagining that the Mexican garrison would resist American incursion, he had expected his troops to be greeted as liberators and friends. Instead, it had taken three days before the city was pacified, hundreds of civilians had been killed, and Wilson was being cursed as an aggressor throughout most of Latin America. The statue of George Washington in Mexico City had been pulled from its pedestal and dragged through the streets. Stunned by the response, the administration retreated from any plans involving further, prolonged occupation.

The president and mayor shared an open carriage during the procession.

The greatest shock for Wilson had come at the news of the American casualties. Back in March, he had worried over the impact of combat on the sweethearts and relatives of the stricken boys; now he had to confront the reality of his fears. “The thought haunts me,” he confided to the White House physician, “that it was I who ordered those young men to their deaths.” Determined to take responsibility for what had occurred, the president had called a press conference to personally announce the results of the fighting. “I remember how preternaturally pale, almost parchment, Mr. Wilson looked when he stood up there and answered the questions of the newspaper men,” a witness recalled. “The death of American sailors and marines owing to an order of his seemed to affect him like an ailment. He was positively shaken.”

As the president’s meditation continued, the carriage turned right onto Canal Street, the main thoroughfare through the Lower East Side. The security detail scanned the crowds with special vigilance. Because of the recent protests in New York, Wilson’s advisers had pleaded with him to avoid the parade. But he had seen it as his duty and insisted on participating. Now the procession was entering the tenement districts, which harbored so many “avowed enemies of government.” Rutgers Square, Mulberry Bend: These were the places where the radicals congregated. For weeks, anarchists and Wobblies had denounced Wilson and his imperialist adventure from these very streets. Factories and shops had let their workers out to view the spectacle, and the sidewalks were filled. The Secret Service men were tense, focused.

The crowds had not expected to see the president, and it took a few moments for them to realize that he had come among them. As the fact registered, the reverent silence that had endured since the early morning finally was swept away. Cheers and huzzahs grew to such a pitch, a reporter noted, that “the demonstration took on almost the appearance of a gala day, instead of one of mourning for the nation’s dead.” Where Canal Street intersected with the Bowery, the youngsters of the Crippled Children’s East Side Free School clapped and shouted, “Hurray for the President!” In the carriage, Wilson busied himself acknowledging the accolades and seemed to momentarily forget his reverie. Then the cortege climbed onto the Manhattan Bridge and processed again in silence.

A million New Yorkers had watched the coffins travel for two hours through downtown, and thousands more awaited them at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The president took his place on a reviewing stand along with Mitchel and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, assistant secretary of the navy. Commissioner Woods and his team of detectives surveyed the crowds anxiously for agitators. The seventeen flag-covered caskets were laid in a row on an improvised bier in front of the dignitaries. The sun parched the hard-packed parade ground; the president removed his hat and gloves, and “with head uncovered, stood looking down upon the scene with grave face.”

Woodrow Wilson had previewed this scene in his mind long before it had come to pass. He had anticipated the concern and confusion he would feel if he ever was required to serve as a wartime commander in chief. Now “his strong voice trembled, and once it nearly broke” as he shared his emotions with the audience. “For my own part,” he said, “I have a singular mixture of feelings. The feeling that is uppermost is one of profound grief that these lads should have had to go to their death, and yet there is mixed with that grief a profound pride that they should have gone as they did, and if I may say it out of my heart, a touch of envy of those who were permitted so quietly, so nobly, to do their duty.” The dead, at least, had been spared the trauma of being president. “I never went into battle. I never was under fire,” Wilson said, “but I fancy that there are some things just as hard to do as to go under fire. I fancy that it is just as hard to do your duty when men are sneering at you as when they are shooting at you.” Such had been his lot as critics had called on him to take action against the nation’s southern neighbor. In the end, he had ordered these men into combat, but he had not done so until he had assured himself of the full propriety of their mission. “We have gone down to Mexico to serve mankind,” he explained. “A war of aggression is not a war in which it is a proud thing to die, but a war of service is a thing in which it is a proud thing to die.” The decision to expose American troops to peril had been agonizing. The consequences—these caskets before them—were appalling. But it had not been in vain.

Veracruz victims crossing the Manhattan Bridge.

He stepped back from the rostrum. A marine rifle squad offered volley after volley in salute, and the crowd began to disperse. From a nearby barracks, a dozen telegraph machines keyed the president’s closing sentiments to the nation.

“As I stand and look at you to-day,” Wilson had concluded, “I know the road is clearer for the future. These boys have shown us the way, and it is easier to walk on it because they have gone before and shown us how.”