Arthur Caron rode to Tarrytown alone on Friday, May 22. Down near the railroad tracks, a few clapboard tenements housed the village workforce. Trudging up steeply rising streets, he was soon passing tidy brick storefronts and prosperous-looking commercial buildings. Then—and it didn’t take long—he was on tree-lined paths flanked by the Gothic and Queen Anne homes where local professionals raised their children. After less than a mile, he was in a countryside not of farms but of estates. High walls stood on either side of the road, hiding secluded mansions belonging to some of the wealthiest families in America.

Accustomed by now to this route and no longer so awed by the scenery, Caron again approached the gates to the Pocantico Hills property. This time, he made a careful survey of the defenses, probing for entry points and vulnerabilities. With the Free Silence pickets abandoned in the city and New York authorities meting out revengeful sentences, he was scouting other means to pressure the Rockefellers. He had briefly mulled a plan to hold a mock funeral march, complete with hearse and coffin, on the road to the estate. But it had proven unfeasible. Now, after a few hours’ investigation, he was convinced it would be equally impossible to trespass on the grounds. He strolled back down to the village and called on the local authorities. At each office, he requested permission to hold a meeting in the public square. These applications were denied—agitators were not welcome in Tarrytown—and Caron departed in defeat.

He promised to return, however, permit or no, to instigate in Westchester County the same sort of free-speech fight that he had led down in Union Square. Caron’s imagination teemed with grand ideas, but his visions never manifested themselves quite as he had planned. In April, he had urged the unemployed to order meals in restaurants and then leave without paying. Nothing had come of it. Then there had been the mock funeral. And now this proposed mass invasion of Tarrytown. So far, few of his schemes had amounted to much of anything. Looking back at his life to date, none of his dreams, really, had come out as he had hoped.

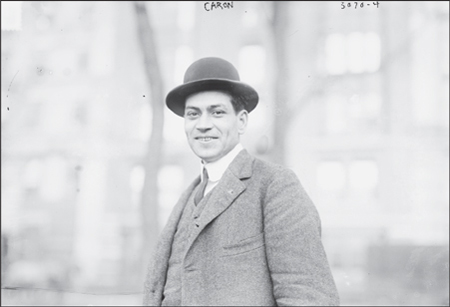

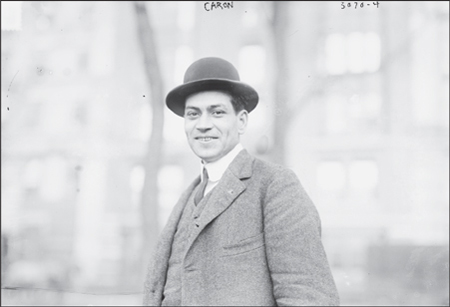

Arthur Caron was thirty years old. Born to French-Canadian parents, he claimed to have American Indian ancestry on his mother’s side. As a boy he had lived in New York State up to around the turn of the century, when the family moved to Fall River, Massachusetts. It was there he received his initial experience of industrial labor. Fifty miles south of Boston, with a population around one hundred thousand, Fall River was the “Queen City of the Cotton Industry,” the “Manchester of America.” The Caron home, on Thomas Street, stood near a cluster of factories where Arthur, and many of his seven siblings, soon found work. Most children in the community left the classroom following the fourth grade to take jobs as bobbin boys or sweepers. Deciding this was not the life he wanted, Arthur determined to better his condition. After his ten-hour shift at the cotton mill ended, he would drag himself to a commercial night school to study engineering, and then finally stagger home and lose himself in his books.

When he was eighteen, Caron left home for a disastrous stint in the navy. As a low-ranking landsman he had served aboard the Constellation, a training vessel stationed in Newport Harbor. The stern discipline had not been to his taste. He was cited repeatedly for “leaving ship without permission” or for returning late from shore leave; a third of his time in the service was spent in hospitals getting treatment for gonorrhea. After fourteen months, to everyone’s relief, he was declared “unfit for service” and discharged.

A civilian once more, Caron remained in Rhode Island and found success. His studies at home qualified him for positions above the mass of laborers; he served as an inspector at the Providence Engineering Works and as an expert mechanic at the Alco automobile factory. His social life thrived as well. He made a reputation as an athlete and married a woman named Elmina Reeves. After a few years they were ready to start a family, and on December 2, 1912, their son, Reeves, was born. Arthur’s fortunes crested here. The child was significantly premature, and three days after its birth, the mother died. Leaving the fragile newborn with his in-laws, Caron returned to the crowded house in Fall River and an unskilled job in a cotton mill.

Since the time he had first entered the factories as a teenager, Caron had been a believer in trade unions, but he had never been the sort to demonstrate or to rant against the owners. His hope had always been to join the managerial class. Back on the work floor again, he came to identify more strongly with his fellow laborers. And in 1913, when I.W.W. locals in Fall River campaigned for higher wages, Caron involved himself with the protests. He did not officially join the Wobblies, but he became known to the police as an agitator. At the height of the conflict, he had gone to City Hall to request a permit to speak in public—much as he would later do in Tarrytown—and when his appeal was denied, the Boston Journal reported, Caron had “made a veiled threat to the effect that his organization would ‘get’ the mayor.”

As a result, he lost his job and fell out with his family. He drifted to Boston, seeking employment, and then arrived in New York City sometime during the winter. Of course, there was no work there either. Despite years of effort and tantalizing moments of promise, he had failed to escape a toiling life. As winter worsened, he sank even lower than before. It had been months since he had held a paying position. Jobless, homeless, and hungry, he stayed at the University Settlement House on the Lower East Side or slept on the street. Some nights, his friends let him use a mattress on the floor of their apartment, on the top story of a tenement on Lexington Avenue at 103rd Street.

Arthur Caron.

Dark and broadly built, he was “about six feet tall” with a well-knit sportsman’s frame. High cheekbones and “a slightly dark complexion” added credence to the rumor of his Indian ancestry. He had a wide, unself-conscious smile that he showed frequently, despite the setbacks he had suffered. “Caron,” a Tarrytown Daily News reporter observed, “appeared to be a jolly, good natured fellow and was continually cracking jokes.” Upton Sinclair thought him “the most level headed and intelligent chap he had known in a long time.” Those who knew him only in passing rarely noticed anything other than this cheery first impression. Trusted comrades observed the other side. To them, he confessed certain details of his past. The stories changed in the telling and retelling, but always they centered around the death of his wife, the loss of his son.

These deeper resentments revealed themselves through his actions. He courted, and even craved, danger. It was a rare protest that did not feature him among the most froward participants. When Craig Sinclair, who had taken a motherly interest in his well-being, warned him against these risks, he had replied, “I made up my mind sometime ago that they would kill me before they got through. I am prepared for whatever happens.” Since March, he had been a leader of the I.W.W.’s Conference Committee of the Unemployed and a frequent orator at Anti-Militarist League meetings across the city. More recently, he had spent much of his spare time with the revolutionaries of the Ferrer Center, and even that bunch was sometimes taken aback by his militancy. “His views were far more extreme than mine,” claimed Marie Ganz, the woman who had stormed into 26 Broadway threatening to murder Rockefeller Junior. “He was a pronounced anarchist who preached the most extreme views.”

Certain themes came up again and again in his speeches. He despised the idea of begging for a reformer’s handout. “If you wanted anything,” he’d say, “the way to get it was to go and get it.” For the authorities, he felt a hatred born of hard experience; nothing pleased him more than provoking an officer of the law. He would point to the men on duty at his rallies and sneer, “When St. Patrick drove the snakes out of Ireland they all came over to America, and from them the breed of policemen were derived.” The cops who thrashed him at Union Square had not been acting at random. “Believe me, when they were clubbing me, they were out to get me,” Caron explained. “When they caught me with Joe O’Carroll and their clubs began to come down on my head they knew what they were about.”

No foe roused in him the kind of hatred that he harbored for the owners of Standard Oil. “‘To hell with Rockefeller!’ was the sentence on which most of his explosive spirit would spend itself,” an audience member recalled. “Caron would flare up till his cheeks and forehead were flaming red upon the theme of Rockefeller.” Week after week, he urged himself to escalate the demonstrations. Dissatisfied by Sinclair’s pickets at 26 Broadway, he had moved the protest to West Fifty-fourth Street, and then pressed on to Tarrytown itself. “Of all the young men and women who came into public notice during the Union Square riots,” a reporter for the Times observed, “Caron was noticed for a constantly growing aggressiveness.”

But the effort came with a hard private cost. He was hungry and tense. All his emotional and physical stamina poured into his work, and the exertions left him shattered and empty; after making his speeches, he would slink down from the soapbox in exhaustion. His wounds had been poorly tended to and misdiagnosed. In between trips to Tarrytown, he checked himself into Lebanon Hospital, where doctors discovered that his nose was broken and infected from neglect. By late May, Marie Ganz was shocked to find him “wild-eyed, haggard, ragged,” and looking “as if he had neither slept nor eaten for days.”

CARON HAD PROMISED to return in force to Tarrytown. But days passed, then a week, and nothing came of it. Rockefeller Senior tested out a system of flashing electric lights that would warn him if any trespassers approached, but so far it had not been put to use. Downstate, where New York City was also enjoying a lull from its troubles, the respite allowed the mayor a chance to manage his critics. To hardliners who believed he had given too much leniency to dissent, he had, in advance of the Veracruz memorial, offered some arrests and a tougher stance against provocations. Confronted by those who believed “no night-stick government is needed in New York,” Mitchel had hedged. He favored tolerance that stretched only so far: harshness, but only as needed. “While it is necessary sometimes for the police to use a certain amount of force in overcoming violence,” he elaborated, “the Police Commissioner and I will stand unalterably against the use of any more force than is absolutely necessary to prevent crime and overcome violence.”

Since February, the radical agitation in New York City had adapted and changed emphasis repeatedly. First, there had been Tannenbaum and the unemployed raids on the churches. Berkman and Edelsohn had then shifted the focus to the conflicts in Mexico and Colorado. Finally, Sinclair and Caron had directed these energies at Rockefeller Junior. The Mitchel administration had responded early on with a persecution that had merely spread the troubles. Taking charge of the police in April, Arthur Woods had attempted more humane methods. But with the Ludlow Massacre occurring just weeks after his regime began, the anger of the demonstrators had not been assuaged by a few signs of tolerance. The mayor had then sought a middle course, one that would not satisfy the radicals but that largely placated his critics among the city’s businessmen and newspaper editors.

Rockefeller’s mansion, Kykuit.

The success of these maneuvers was shown during Alexander Berkman’s latest “monster mass-meeting” at Union Square. When the day came, “the afternoon was balmy, and every bench in the park was occupied. Yet, with all the favorable circumstances, Berkman brought fewer than 200 sympathizers,” and the assembly “was a tame affair in which most of those present soon tired of the oratory and yawned back at the speakers.” Detectives Gildea and Gegan looked on lethargically, and even Becky Edelsohn made an oration that “was much less radical than on former occasions.” Affairs were even more demoralized for the Industrial Workers of the World. Local 179—Tannenbaum’s own chapter—had sunk back to its former languor. “About a dozen come to the weekly business meetings now,” a member confided to Frank in prison. “The Sunday meetings, held indoors, were so poorly attended as the warm weather came on that we are giving them up.”

The moment seemed bleak, but at least the Industrial Workers of the World had people talking. The head worker at the University Settlement, where Caron often stayed, had been impressed by the Wobblies he had seen. “Compared to the Bowery type of hopeless ‘down and outs,’ the leaders of the I.W.W. are intellectually keen and are even red blooded,” he said, “and since their purpose was to get publicity they may be said to have been a ‘howling success.’” But with the recent malaise in radical circles, this had become a minority view. “They were after publicity, and they got it,” editors at the Tribune admitted. “If that is the measure, they were a success. They are the most ingenious self-advertisers in the world, though they have some clever imitators in Upton Sinclair and Bouck White. But aside from self-advertising what did they accomplish?” Victor Berger, the Socialist congressman from Wisconsin, passed through New York and was besieged by questions about the local agitation. “The whole affair is absolutely foolish,” he replied. “It has been an instance of fanaticism run mad. There is no reason why the Rockefellers should be afraid. They are being assailed only by some crazy, overheated, excited people, who want to talk their heads off, but who have neither desire nor intention to do anything else.”

Bill Haywood was the only one able to move beyond criticism to analysis. In April, Berkman’s broadsides had brought thousands of demonstrators to Union Square; a month later, the anarchists were able to draw only a few hundred listless disciples, and Big Bill knew the reason why. “With the clubbing came the converts,” he explained, “and after there was no more martyrdom there were no more additions to the ranks.” The Jacobins, in other words, could not succeed without an obstinate ancien régime to oppose them.

BY MAY 30, Arthur Caron was through waiting for his permit. With eleven others, including Becky Edelsohn, he took the circuitous ride northward, hopping off the trolley onto Main Street, Tarrytown, around nine P.M. It was Saturday night, but the byways were quiet and mostly empty. The group walked down Orchard Street to Fountain Square, the traditional site over the years for revival meetings and Salvation Army drives, where a few residents were enjoying the warm evening. No one really paid much attention to Caron as he stalked from the sidewalk out into the middle of the street, deliberately set up a soapbox, and then stepped on top of it. The others clapped as he rose, to attract attention.

Main Street, Tarrytown.

“Did you ever hear the wail of a dying child and the wail of a dying mother?” he cried out. “They were murdered in Colorado while the American flag flew over the tents in which they lived, and the murderer was John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who lives in this—” and, before he could finish his sentence, a police officer dragged him from his perch and into custody. “No sooner did Caron’s feet touch the ground,” a witness wrote, “than another member of the band stepped up on the box, only to descend even more quickly than Caron, with the assistance of another policeman.” Becky was next. She managed to say, “The only thing John D. Rockefeller ever gave away was oil to burn the mothers and babes in Ludlow,” and then she too was seized. One and then the next, each anarchist was detained in turn, until all twelve had been arrested. Placed together in two cells, the eleven men immediately made themselves a nuisance. “They began to sing boisterously and kept time by pounding on the iron bars with any implement they could lay their hands on.” No one in the neighborhood could get to sleep for hours. “This is a stale joke,” remarked Becky when she was led into the little-used women’s lockup and introduced to her cellmate: She’d be sharing her quarters with the police department chicken.14

Berkman arriving in Tarrytown.

Alexander Berkman didn’t linger when he learned the fate of Caron’s party. Gathering a dozen others with him, he rode north the next morning, May 31, and arrived in Tarrytown at one P.M. Having come to agitate, he had no trouble getting the locals swarming. They awaited him at the train station and chased him with jeers and threats, hustling him ahead whenever he paused. The anarchists ended up wandering for several hours in search of a place to gather. “They kept protesting all the time that they had the right of free speech and intended to exercise it.” But onlookers and police had no notion of allowing this. Berkman was chased from Tarrytown to North Tarrytown and back; he and the others were shoved and antagonized. And if a radical answered back, the officers took the chance to tackle, punch, and arrest him. Over the course of the day, three additional anarchists were seized. With his forces dwindling, Berkman called for aid. Twenty more men hurried up on an evening train, but by then the mob had lost patience. Unconstrained by the police, the locals attacked. “What followed,” thought a reporter, “looked like a scrimmage between half a dozen football elevens. Men were swept from their feet and kicked and stepped on.” It was ten P.M. before the authorities were at last able to calm their own neighbors enough to reinstate some order. Berkman and the others were paraded to the station and forcibly loaded aboard a southbound train.

Becky Edelsohn under arrest.

The village courtroom was hushed and tense when Caron, Edelsohn, and the rest of the original twelve agitators were brought in for their arraignment that evening. Officials had been working for hours on their case; most of the men in town, and all twelve members of the police force, had been on duty for days without a break. Clerks consulted in whispers with attorneys; spectators slumped exhausted across the benches. No one spoke. “This is a solemn occasion,” Becky said, breaking the silence. “I would like to borrow a handkerchief from some kind soul to weep on.”

“Becky—” called a reporter, with some query.

“My name is not Becky to you,” she snapped back. “It’s Miss Edelsohn.”

The sheriff noticed a book she was carrying—Beyond Good and Evil— and asked who the author was. “It’s by a well-known convict,” she hissed. And after that, no one else asked her any more questions. When the town justice informed the defendants that they had been charged with “disturbing the peace, blocking traffic and endangering the public health,” Miss Edelsohn leaped up in a fury.

“What do you mean charging us with blocking traffic, when you haven’t got any traffic in this town to block?” she demanded. “This whole charge is fictitious and a gross lie. There ain’t enough people in this town at nine o’clock to block anything. You would have to come here at two o’clock in the afternoon and then you would find half the town asleep.” As for the accusation of threatening public safety, she had some choice words on that matter, too. “My God! Endangering lives!” she said, as the court officers swapped nervous looks and shrank into their seats. “You endangered lives of our men by locking six in a cell. And you placed me in a lockup which you used as a chicken coop. Why don’t Tarrytown build a hencoop of its own? But we don’t expect any better justice in this town, which is owned by John D. Rockefeller.”

The defendants refused to have attorneys appointed, demanding to be returned to their cells; they would make the village accommodate them until the trial. The vision of eleven noisy anarchists banging on the bars night and day was not a good one for the sheriff. But the prospect of spending more time with Miss Edelsohn—the “tarter” with “an awful tongue,” as a local reporter described her—went far beyond evil. Pleading inadequate accommodations, the police decided to transfer their prisoners to White Plains, the county seat. At midnight, relieved townsfolk watched as five automobiles, carrying the agitators, disappeared down the dark roads and out of sight.

CLUBS HIT HEADS WHEN I.W.W. RAIDS J.D.’S “OWN TOWN” was the big headline in the World on the morning of June 1. “Twelve I.W.W. agitators in jail, Alexander Berkman sent back to New York with his gang of anarchists; the whole police force of Tarrytown on continuous duty for twenty-four hours,” called the Sun. “This, in brief, tells the story of the most riotous night and day this Sleepy Hollow country has ever known.” Nearly a century had passed since Washington Irving had chosen this area as the setting for his stories. “A drowsy, dreamy influence,” he had written in 1820, “seems to hang over the land, and to pervade the very atmosphere.” Since then, the New York Central Railroad tracks had tied the village to the city, and some parts of the main street had been paved with brick. But otherwise, residents liked to think that little had changed. “Our people retain their old Dutch conservatism,” the editor of the local newspaper proclaimed. “We are a steady people.”

In fact, the countryside had been transformed by arriving “nomads of wealth”—flourishing industrialists in search of a place to homestead. They were drawn by the proximity to Grand Central Station, as well as the area’s reputation as “an unwavering Republican stronghold.” The Rockefellers had claimed the choicest parcels, but they were joined by Goulds and Beekmans until Tarrytown was believed to be “the home of more millionaires than any other town of its size in America.” These families were perceived as generous benefactors—they had dedicated schools, churches, and roads to the community—and now that they were under threat from outsiders, most residents were inclined to repay their generosity. “Public opinion is with Mr. Rockefeller. It has little sympathy with the ‘mourners,’ “reported the local paper. “No Capitalist that ever lived … was ever more of a parasite upon society than this crew of hoodlums and blasphemers who preach a gospel of riot and murder in the name of labor.”

Having read for months about the radical uprisings down in the city, the citizenry was primed for panic. “Unrest among the so called Industrial Workers of the World, anarchists, and other kindred organizations has never before been pitched to such fever heat as now,” the Tarrytown Daily News had recently informed subscribers. “The anarchists have never had fuller sweep in their scope of murderous endeavor in any country or in any city than they are now being given in New York.”

Terrified that these ordeals were soon to be visited on their own hometown, the local authorities lost all composure. The police chief swore in fifty deputies and outfitted them with clubs. The fire chief attached hoses to the hydrants, so that water could be pumped onto the protesters. The menfolk promised to tar and feather any outsiders and then dump them in the river. Volunteers watched the roads into town. Observers positioned themselves at the railroad station and the hotels, accosting every stranger who arrived. Paranoid reports of invading Wobblies came from all quarters: Twenty had been seen approaching from the south, they would mob the jails, they were sneaking in one by one. When Berkman suggested that he and his followers would come and slumber outside in Fountain Square, the town disfigured its own streets with a thick coat of asphalt. “They may sleep on that if they care to,” a policeman laughed as he surveyed the mess with satisfaction, “but there’s no telling when they’ll get up.”

The radicals responded with threats of their own. Berkman described a regiment of mad anarchists—from the northwestern timberlands, the Rocky Mountain coalfields, the city ghettos—that would march, unstoppable, on Sleepy Hollow. “Threats of bloodshed or ducking do not alarm us,” he said. “We have been treated in Tarrytown worse than Russian Cossacks treated serfs. If any one made disorder there it was the police, not our people. The Constitution is greater than any village ordinance, and it guarantees to every man and woman the right of free speech. We mean to have this even if it costs blood and imprisonment and the peace of the Rockefellers.” While his army coalesced, he wasted no opportunity to rile the city farmers of Westchester County. In Mother Earth, he wrote:

A tiny village on the Hudson some twenty miles from New York has been placed on the map within the past two weeks and is now as well known as Trinidad, Col. This sleepy little burg is a suburb of one of John D. Rockefeller’s estates and hitherto has been known only to commuters from Poughkeepsie and Ossining on their way to New York. The Anarchists and some members of the Ferrer Association have suddenly thrust fame upon this unoffending village by trying to hold meetings under the shadow of the town pump.

The marauding anarchists, and the panicky residents, had brought the village a notoriety it had not wanted. “Tarrytown is the laughing stock of the country today,” a local editor complained. “Commuters who go to New York told us last night that they don’t dare say they are from Tarrytown. New Yorkers who know them jeer and boo them. It is a pretty spectacle!” From afar, the city papers showed unbecoming glee in seeing another community undergo the troubles with which they had become so familiar. “It is impossible not to sympathize with the people of Tarrytown in their aversion to having their town made the rendezvous and forum of this I.W.W. riffraff,” wrote an editor at the World. “Everybody has a right to a peaceful life, liberty from noisy mountebanks and the pursuit of sleep—if he can get away with it.”

A week earlier, the Mitchel administration’s policy of limited tolerance had brought the radical cause to a frustrated impasse. The press had lost interest. Attendance lagged worse and worse at every protest. All of this was now reversed. The anarchists, with the unintended assistance of the Tarrytown authorities, had discovered the perfect platform for their agitations. Only thirty miles north of Union Square—but a world away from the jurisdiction of Commissioner Woods—Arthur Caron had found his Bourbons.

The Tarrytown train station.

* * *

WORKMEN AT POCANTICO HILLS reported glimpsing “a pale and haggard” Rockefeller on the occasions when he left his father’s mansion. The chances to see him were rare; he had hardly strayed more than a few hundred feet from the house in weeks. He had spent years meticulously landscaping the grounds, choosing the fountains and statuary, making the gardens into places of comfort and introspection. With Caron and his threatened anarchist militia expected hourly, that serenity had vanished and the family estate had become a militarized encampment. Four guards, armed with automatic pistols, were stationed at every gate; rifles were stacked and ready in the guardhouse. Sixteen of Tarrytown’s new special deputies were posted to Pocantico Hills on rotating twenty-four-hour shifts. Burns detectives loitered in the shadows.

Letters continued to appear, and not all of them offered solicitous encouragement:

You fooled us last Sunday + the Sunday before but you wont fool us much longer we will get you & your father yet Maybe next Sunday in Tarrytown, Yonkers, or wherever you go look out.

I.W.W.

Dear Sir,

I have fully made up my mind to assassinate you … As I am an expert rifle shot I guess I can pick you off regardless how many detectives or guards you have around you …

Yours, A Sufferer of Capital

These were filed away, or passed on to the Burns investigators. But letters from sympathetic strangers could be just as upsetting. People he had never met offered to commit violence in his cause. Several writers offered unsolicited advice, almost all of it corrupt and repellent. A businessman informed Junior that he was on the verge of purchasing Century—“the most influential, and in many respects the greatest, magazine in the country”—and in exchange for Rockefeller financing, he could promise sympathetic coverage of the Colorado events. “There is such tremendous pressure brought on writers just now to inflame class hatred,” the author explained, “that it might be worth while to have a big sane organ voice the truth.”

Another proposition came from Isaac Russell, the New York Times correspondent who had drawn the unwelcome assignment of insinuating himself among the protesters. “As a reporter for the Times,” he clarified, apologetically, “I have had, of course, to keep in close touch with all the various groups who have created disorder hereabouts for several months.” They, in turn, had come to accept him. Considering Russell a friend and “an honest man,” Upton Sinclair had even entrusted him with secret correspondence divulging some of the future plans of the Free Silence League. Now the reporter forwarded this document to Rockefeller. “I have not shown the letter to anyone,” Russell wrote to Junior, “and I shall never tell anyone that I have sent it on to you.”

After all these months of passively accepting the facts that Bowers presented to him, Junior had finally lost faith in the Colorado executives. He began to cultivate alternate lines of intelligence, receiving telegrams from trusted sources in Denver that gave a more critical view of the operators’ actions. But when he tried to go further—to take positive steps toward reform—his colleagues blocked him. They absolutely would not condone anything that could undercut the company’s position while the strike persisted. Rockefeller had the idea of sending Raymond B. Fosdick, a researcher for his Bureau of Social Hygiene, to make an unbiased study of living conditions in the mining camps. “I feel quite strongly about this,” he insisted, “and hope the idea may commend itself to the rest of you.” His jaded subordinates tactfully killed the plan. “My first instinctive reaction was one of doubt as to the wisdom of this suggestion,” replied Starr Murphy, his attorney. “I feel that the fight has got to be fought out to a finish. When it is finished, I should cordially favor an investigation and a report with a view to vindicating the Company if the facts justify it, or as furnishing a basis for reforms in future if the report shows changes to be necessary. But that will have to be deferred until the present fight is won.”

Of all the unsettling communications he had received, none spoke more closely to his deepest concerns than a note from the secretary of the interior—one of the many officials who had tried, and failed, to convince Junior to step out from behind the actions of his counselors. “I am very sorry,” the letter began. “I believe that I have urged you to a course that in the future your conscience and your intelligence will commend as the only wise one. I have spoken to you as your friend: There is no man who can decide for another what his personal course should be. Your ideal of yourself, not as a maker of money but as a doer of good, should determine every time your course of action without respect to what your advisers say.” But while Rockefeller was unwilling to ignore the iniquities of business, he was equally unable to intercede against the executives of Colorado Fuel & Iron. He let his integrity dictate his choices, but not to the point where they could affect his father’s interests. By refusing to make the hardest decision, he had sentenced himself to an existence of subterfuge and violence. For someone who honored probity and candor above other virtues, this was hardly a life at all.

Which is why it was such a relief to meet Ivy Lee. A southerner just a few years younger than Rockefeller himself, Lee had graduated from Princeton and attended Harvard Law School. He then worked as a reporter in New York before switching careers and revolutionizing the field of corporate publicity. He was currently engaged on a campaign for the Pennsylvania Railroad, but the Rockefeller account was too plummy to pass up. “I feel that my father and I are much misunderstood by the press and the people of this country,” Junior said to Lee during an interview on June 4. “I should like to know what your advice would be on how to make our position clear.” Junior had corresponded with several fast-talking public relations men in recent weeks, and he had been perturbed by their willingness to manipulate and mislead their targeted audiences. Lee, the drawling gentleman, deprecated the use of lies, or paid advertisements masquerading as news stories. No publicity, he argued, was ever so effective as the truth. “This,” an ecstatic Rockefeller replied, “is the first advice I have had that does not involve deviousness of one kind or another.” Lee was immediately retained at the fee of a thousand dollars a month.

Ivy Lee.

“Desiring as I do that you should understand some of the ideals by which I work,” Lee wrote to Rockefeller a week later, “I am venturing to inclose you a manuscript copy of an address I delivered before the American Railway Guild in New York some weeks ago.” Lee’s speech presented the outline of his philosophy of public relations. Crowds did not reason, he argued, but were guided by symbols and stories. There was no point in offering in-depth statistics, since the majority of Americans would be convinced by a few choice tidbits. Reduced to its simplest expression, he practiced “the art of getting believed in.” Strongly denouncing the publication of outright lies, he suggested a more nuanced approach: “We should see to it that the public learns the truth in all matters, but we should take special pains to see that it learns those facts which show that we are doing our job as best we can, and which will create the idea that we should be believed in. We must get so many good facts, so many illuminating facts, before the public that they will overlook the bad.”

Putting these ideas into practice in the coal controversy, he submitted for approval Bulletin No. 1, in what would be a series of weekly pamphlets stating the truth—as Junior wanted it to be. “It is of the utmost importance that every American citizen should understand what has really been going on in Colorado,” the publications explained. “The facts have been beclouded with unusual venom.” The leaflets were to be “dignified, free from rancor, and based as far as possible upon documentary or other evidence susceptible of proof.” Several key passages each week were underlined in black:

In the present issue we are not opposing or waging a war against organized labor as such.

The issue in Colorado has ceased to be, if it ever was, one between capital and labor.

Shall government prevail, or shall anarchy and lawlessness rule?

Junior quickly gave his endorsement, and Lee prepared to distribute the document to a catalogue of “thoughtful people” he had compiled. His list contained eleven thousand entries, including “about 3,500 newspapers, all members of Congress, all members of state legislatures, the mayors of all cities having a population of over 5,000, teachers of economics in colleges, and … every one whose name is mentioned in the latest issue of ‘Who’s Who in America.’ “Lee’s plan relied on convincing these people. “It is thought that by sending these leaflets to a large number of leaders of public opinion throughout the country,” he wrote to Rockefeller, “you will be able to get certain ideas before the makers of that public opinion which will be of value.”

But it was not enough to print the truth and then broadcast it widely. The bulletins needed to appear trustworthy. Recipients were not to realize that these reports had been composed by a publicist at 26 Broadway—the pamphlets had to come from somewhere else. “This publicity work on behalf of the operators,” Junior wrote to an executive at Colorado Fuel & Iron, “while even more important in the East, as things now are, than in the West, must, of course … emanate from Denver. All of the bulletins and other matter which Mr. Lee is suggesting will be mailed from Denver.”

And so Rockefeller set out to spread the truth.

* * *

UPTON SINCLAIR HAD gone to Denver to get a firsthand view of the strike zone. All it took was a few days in Colorado and he had already been denounced by the governor as a “prevaricator” and an “itinerant investigator.” He had also managed to instigate a feud with local journalists as well as the Associated Press. “What next fool thing will Upton Sinclair do to get his name in the newspapers?” asked a reporter for the Los Angeles Times. “He comes perilously near being a pest.”

Undaunted, he traveled to the mining districts, toured the ruined camps, and talked to anyone who would talk to him. The professionals and society folk he met described their anxieties during the previous months. “It was touch and go—like that!” a lawyer told him, snapping his fingers. “We almost had a revolution.” The stories he heard from the miners and their wives kindled in him the same sort of ache he had felt, years earlier, for the workers of Packingtown, in Chicago. Once again he was determined to pressure Rockefeller into admitting his sins. “About a month ago I addressed a letter to you on the subject of the Colorado strike,” Sinclair wrote to Junior in late May.

At that time I had only hearsay evidence concerning the situation; but now I have been upon the scene, and have talked with scores of victims of the crimes that have been committed. I have met a mother who was made a target for militia bullets while she dragged her two children away from the blazing village of Ludlow; another whose three children were left behind to perish in that inferno. It seems to me as if the air I breathed were full of the smoke of powder and the scent of burning human flesh; as if my ears were deafened with the screams of women and children.

Sinclair returned to New York and replaced the defunct Free Silence League with a new organization that operated out of his apartment. Pausing momentarily in his protests, he assisted in a screen adaptation of The Jungle. The author was certain that his venture into the movies would be a success, especially since he would be appearing on screen, playing himself, in a sort of prologue to the feature. He was already spending, in his mind, the millions he would earn; it was left for Craig to make sure he did not do so in actuality. The film ended up being banned in Boston, and though it ran for a few weeks in New York City, the company went bankrupt and the Sinclairs never saw a penny.

Catching up on events, he found the city newspapers bursting over the latest agitation. “Edition after edition appeared, each one with new alarms upon the front page,” he recalled. “The I.W.W. was marching upon Rockefeller’s town from all over the United States! The anarchists were plotting bombs and assassinations! The authorities of Tarrytown had hired fifty special officers, each armed with a hickory club and two loaded revolvers!”

For once, the itinerant investigator hesitated. This frenzy was even greater than the furor over the mourning pickets, and after the scathing abuse he had received during the previous weeks, Sinclair feared to involve himself in Westchester County. “One had to be reckless as to his reputation,” he reflected, “when he meddled in that story.” Furthermore, he and Craig were destitute and exhausted, and his wife felt they had done their duty. “We had let the public know what was wrong,” she argued, “and now surely it was up to the public to protect its own free institutions.” But Sinclair could not bear to miss a chance to involve himself. He went to Tarrytown and demanded free speech. When the village authorities refused him the streets, he made them promise to find a private auditorium in which to hold his meeting. The owners of the Union Opera House and the Music Hall refused to rent to the radicals, and so Sinclair enlisted a wealthy village resident—Mrs. C. J. Gould—to let them use her lawn. The Tarrytown Daily News attacked him relentlessly, turning on its own local officials anytime they acceded to his requests. But he was no longer willing to play the victim. One morning, the editors of both local newspapers found themselves under arrest: Upton Sinclair had sued them for libel.

On June 6, he traveled to Tarrytown to see the trial of the twelve imprisoned anarchists as a correspondent for the Appeal to Reason. Caron, Edelsohn, and the others had spent the previous week in the White Plains jail. “To read the accounts of the arrested agitators, you would have thought they were maniacs or wild beasts,” Sinclair wrote. “They howled and made pandemonium in their cells. They cursed and reviled God, and the Pope, and the chief of police of Tarrytown.” Facing a year in prison, as well as $500 fines, the anarchists enlisted Justus Sheffield, who had represented Frank Tannenbaum, to conduct their defense. The attorney managed to gain a series of postponements that delayed the trial for a month. In the meantime, Berkman had scrambled to gather money for bail. On June 8 he handed twenty-four hundred-dollar bills to the village officers, and the twelve inmates were released.

“But you can bet we’re coming back,” Becky informed the spectators who tailed them from the jail to the station. “We are going to show them in Tarrytown that we can hold meetings there in spite of their old police force. We’ll answer violence with violence … It’s a matter of principle now.” They rode the Harlem Line down to Morrisania station in the Bronx, where scores of anarchists were waiting to cheer their arrival. Then a rowdy impromptu parade took them to the Ferrer Center, where the freed agitators were greeted to a triumphant welcome.

Nothing so far had occasioned the sort of exposure that the anarchists were earning from their Tarrytown protests. “The most astonishing situation in the history of the United States exists in Pocantico Hills,” the Day Book of Chicago asserted. “Thirty-six dollars and seventy-five cents have one billion two hundred million eighty-nine thousand dollars surrounded, blockaded and balked … John D. Rockefeller, the richest man in the world, and his son, John D., Jr., are today as close prisoners in their estate as are the convicts in Ossining penitentiary.”

The standoff made headlines in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, the Olympia Daily Recorder, and the Aberdeen Daily News, leading to a national debate over civil liberties. “The right of free speech is guaranteed under the constitution,” an editor at the Grand Forks Herald conceded, before continuing on to say, “but there is another right that is inalienable, and that is the right of silence. If a man enters your house and wants to talk to you, and you do not want to hear him, you tell him so.” While few went so far as to cheer the anarchists, there were observers everywhere who demanded they be given an opportunity to express themselves. “What these spouters were and what they spouted is immaterial,” argued a writer for the Memphis Commercial Appeal. “They may be either fools or patriots; they may be forgotten tomorrow or have statues erected to their memory a hundred years hence. The important fact is that they have been denied their rights.”

For Arthur Caron personally, none of the publicity was more satisfying than an article Sinclair had written for the June 20 issue of the Appeal to Reason. The author described a vaguely familiar person: a young man who had happened to be in Union Square in April, when he had witnessed the cops attacking some protesters. “He was a boy with no idea whatever about radical matters,” Sinclair explained. “He had neither read nor thought about the class war. But he saw this outrage and from pure human sympathy rushed forward, crying out in protest. Instantly two policemen fell upon him, and began to club him. They did not stop until they had laid him out insensible. They broke his nose; and they also opened his eyes.” This character, naturally, was Arthur Caron himself, or at least the version Sinclair had chosen to see. Despite all his empathy, the author was an appalling failure at judging others. But even for him, this characterization of his fellow radical as a naïve youth was absurd. “Caron told me that he did not know whether he was an anarchist or Socialist,” Sinclair continued, “because he had had no time to find out what either meant.” For the actual Caron, the episode was an absolute joke. He carried the article in his pocket when he attended protest meetings and showed it around to his comrades, laughing at the portrayal.

TWO WEEKS HAD passed since the prisoners had left the White Plains jail and returned as heroes to New York. Their trial had been rescheduled for early July, and the village police assumed that was when the next demonstration would occur. The new tar in Fountain Square had dried. The deputy policemen had returned to their civilian jobs. There had been so many false reports that nobody took seriously the dispatch on June 22 that the agitators were coming. But when the six P.M. local from Grand Central arrived at Tarrytown station, eighteen radicals stepped down onto the platform. At first they loitered, seemingly without a plan, but then the 8:20 train arrived and another forty or so disembarked. No more hesitation. The sixty anarchists marched with swift strides up Main Street, singing “The Marseillaise” and gathering a following of vengeful residents.

“Like the minute men of’76,” a reporter wrote, “Tarrytown’s harassed villagers went forth to repel the foe.” A crowd of five hundred men trailed the demonstration as it turned left on Broadway, passed the village president’s flower shop, and then veered again onto McKeel Avenue. There they paused in front of a narrow strip of lawn that formed the right-of-way for the old Croton Aqueduct. Technically, this was New York City property, and it was here that the anarchists intended—at last—to hold their meeting. The mob around them knotted tighter, an enraged semicircle, with a band of automobiles forming the outer ring. Berkman grabbed a soapbox and positioned it under the glow of an arc lamp. When he climbed on top of it, the chief of police shoved him down, but then another anarchist leapt up and the outnumbered officer hurried off for reinforcements.

Becky Edelsohn was the first to try and speak. She rose and held up a hand for silence, which prompted a chorus of jeers.

“You cowards!” she cried. “You curs!” A man in the front of the throng hurled sand in her face. Then a second handful hit her in the mouth, and she choked. And finally dirt was heaped on her from three sides, and Berkman had to hold his hat in front of her eyes to protect her. “She held her place for twenty minutes,” a witness wrote, “and made a plucky fight against the hoots of the crowd and the charge of sand and sod thrown at her.” When she stepped aside, at 9 P.M., Berkman himself took her place on the platform. The mob had reserved their best ammunition for this moment. “We demand the right of free—” was as far as he could get before a squall of rotten eggs, cabbage, and tomatoes flew toward him. Sods of dirt struck his face and yolks covered his clothing and ran down into his collar as a stone knocked him down from his perch into the arms of his comrades.

Then Arthur Caron stepped up. The halo from the street lamp marked him out against the night, while his persecutors all were masked by darkness. As he spoke, the taunts resumed in even greater torrents. “Caron has a strong voice,” a reporter for the Tarrytown Daily News observed, “and when he began shouting the jeers of the crowd could hardly drown his voice so the owners of automobiles, which were stopped in the street, began tooting their horns and the din could be heard blocks away.”

“I was born on American soil,” he began.

“How do you like this soil?” came the response, as a sod clump struck his mouth. “This marked the beginning of a bombardment,” a newspaperman wrote. “From every part of the crowd came missiles. There were eggs, many of them; stones, vegetables, clods of dirt, sticks, and uprooted sod.” The police stood by, making no effort to intercede.

“I have Indian blood in my veins,” Caron shouted in the midst of the onslaught, “and you cowards who are throwing this dirt are traitors to the flag.” At that moment, a stick smacked him in the jaw, broadside on. Bleeding from his mouth, livid, he continued defying the mob until Berkman and the others dragged him—unwilling, resistant—from the box. They had accomplished their goal of bringing free speech to Tarrytown, in spite of itself, and now it was time to get out. The anarchists filed from the aqueduct property and headed for the station, while the police strained to hold off the throng. “We want Berkman!” they cried. “Let us have him!” “Lynch Berkman!” It took only a moment for the mob to loose themselves from restraint. One concerted rush bowled over both the anarchists and the police. “The Crowd swarmed around like bees.” A passing trolley had its windows smashed. Berkman was separated from the rest, pinned against a wall, and beaten until the cops came to his aid. Then he and the others were all hustled down the hill to the station.

Hundreds of rioters packed the platforms and filled the nearby streets; passing trains skulked by to avoid the spectators who spilled out onto the tracks. Finally, the 10:50 southbound local crept up to the far end of the platform, and two rows of policemen, with clubs drawn, faced down the onlookers while other officers shoved the anarchists into the smoking coach.

“Go back to New York where you belong,” the locals crowed.

“We’ll be back again,” shouted Becky, still defiant, as the locomotive jolted forward.

Then they were in the quiet of the car. Berkman’s clothes were torn and ruined, his face smudged with dirt. Becky’s eyes were red and swollen from the sand, her dress “a yellow Niagara” of egg drippings. “Caron was the most severely injured,” a reporter wrote. “His jaw was badly cut and his lips were so swollen he could hardly talk.”

THE NEXT MORNING, some were in the mood to gloat. “The anarchists who have been howling for any opportunity to air their views in Tarrytown had an educational experience when they took the police by surprise on Monday night,” editorialized the Sun. “They succeeded in coming face to face with the plain people and they learned exactly what the plain people thought of them.” But a writer for the Times better understood what he had witnessed. Most previous demonstrations had merely “defied John D. Rockefeller, Jr.” Some had called “for a peaceful agitation for free speech, others for a radical movement, but the leaders usually were restrained from going as far as they liked.” This latest escalation by the anarchists represented something new. There could be no reconciliation after such a battle.