By mid-August the coal war had entered its eleventh month, although it had fallen from the public view since April, when federal troops had arrived to stem the violence. Nevertheless, several thousand miners, weary and increasingly demoralized, still occupied various tent colonies in the district. But they had become little more than an inconvenience. The Colorado Fuel & Iron Company was operating its mines at three-quarters capacity, working them with replacement labor. It was apparent that the strike, though still ongoing, had failed. Surely, thought Rockefeller, the time had finally arrived to initiate reforms. He had received a settlement offer from the vice president of the United Mine Workers of America, and he inclined toward pursuing it. Bowers blocked the idea. “To move an inch from our stand at the time that defeat seems certain for the enemy would be decidedly unwise, in my opinion,” he wrote to Junior. “We are encouraged to stick to the job till we win.”

Through the autumn, as they had since the start, Bowers and his intransigent colleagues resisted every proposal of arbitration and reconciliation. In September, President Wilson and his secretary of labor suggested a resolution that granted every one of the coal operators’ demands—it did not even require the companies to recognize their workers’ rights to organize. This was the one issue that the owners had insisted upon, and now they had got their way. The union, approaching the end of its stamina, accepted the deal. Seeking only unconditional surrender, the coal operators did not.

Finally, on December 10, 1914, after fourteen months of struggle, the employees voted to end the strike. The United Mine Workers estimated it had paid out more than $3 million in benefits, while its members had sacrificed twice that amount in lost wages. At least seventy-five men, women, and children had been killed.

“The feeling of satisfaction on the part of all of us is by no means small,” Bowers wrote to Rockefeller one day later. He had seen himself as waging a titanic moral struggle—opposing all attempts at interference, resisting every temptation to compromise—and now he exulted in victory. “Our rugged stand,” he wrote, “has won us every foot we have gained.” He had no sympathy for the families who had tried to unionize and who now faced winter in the knowledge that no company would hire them; their future, he sneered, “must be very discouraging.”

Bowers did not have long to gloat. He had always said that the end of the strike would mean the time had come to examine the company’s conduct. Now that this had occurred, Rockefeller made the one change he thought most pressing. On December 28, he called Bowers to his office at 26 Broadway. In a bitter and painful interview, he ordered the older man to resign his directorship, his place on the board, and every other position—official and unofficial—that he held at Colorado Fuel & Iron. Hoping to retain a scrap of his former authority, the executive suggested he might at least remain in communication with his former staff. Using the same phrase that his subordinate had so often used against him during the preceding months, Junior replied that such a decision “would be unwise.” Bowers was offered a year’s salary as severance, and the prospect of a nice vacation. “We want to have you take the next two or three months for unbroken rest,” said Junior, soothingly. “I fancy you must feel more or less like a colt turned out to pasture.”

Just as he discarded one troublesome employee, however, Rockefeller found himself accounting for the excesses of another. During government hearings in December, Colorado Fuel & Iron officials had been compelled, under oath, to reveal the true author of the series of pamphlets that had been issuing forth from their offices since June. Forty thousand had been sent, at a cost of $12,000, and the tone and scale of the effort had made scrutiny inevitable. Ivy Lee’s months of work were undone in a hail of criticism. “The strike bulletins,” wrote editors at the Survey, “were shown to be not only biased ex parte statements, but to contain gross misstatements of the salary and expense of the Colorado miners’ leaders.” A close reading revealed—among other fabrications—that Lee, attempting to discredit the opposition, had exaggerated union officials’ wages by a factor of ten. ivy l. lee—paid liar, declared a story in the Call. Upton Sinclair dubbed him “Poison Ivy.” Attempting to cover up the extent of the manipulations, the company at first denied that Rockefeller had played any part in the campaign. But internal correspondence revealed the extent of his complicity. “More systematic and perverse misrepresentations than Mr. Lee’s campaign of publicity,” the Masses proclaimed, “has rarely been spread in this country.”

With anger still fresh, Rockefeller and Lee were called to testify before the Commission on Industrial Relations, the federally funded tribunal that had been traveling the country since 1912, examining the causes and consequences of labor disputes.

January 25, 1915, was a snowy, sleet-spoiled day in the midst of another hard New York City winter. Rockefeller strode through the front door of City Hall: On Ivy Lee’s advice, he had abandoned the habit of sneaking in and out of back entrances. On Commissioner Woods’s insistence, he was flanked by several uniformed policemen and half a dozen detectives, including the mayor’s own personal bodyguard. He climbed the stairs to the Common Council chamber, where his interrogators awaited him.

Rockefeller Junior on the stand.

The audience, which the Times observed “was in large part frankly hostile,” had come for its first glimpse of the man behind the Ludlow Massacre. During all the months of protests and persecutions, he had never allowed himself to be seen. Tense and nervous, “his platoon of shifty, active guards” kept at the ready. “Constantly they eyed every man and woman in the City Hall room where the hearing was held.” The whole assembly was against him, and no one more so than the commission’s chairman, Frank P. Walsh, a midwestern attorney who knew he faced one of the most important witnesses of his entire career.

The questions came quick and angry, with no purpose but to embarrass or implicate Rockefeller as a cold tyrant and a shiftless son of wealth, an autocrat and an absentee ruler. With twenty or so cameras aimed at him, Junior managed to stay poised. But his answers did not satisfy anyone. He hedged and stalled, refusing to clarify his general opinions about organized labor, trying as hard as he could to distance himself from Ivy Lee and his publicity work. “Wary and bland” was the Times reporter’s evaluation of his performance. By the end of the first of two days of testimony, the audience had lost its savor for the spectacle; the hectoring examiners, the evasive witness—neither party could succeed in winning favor under the conditions.

No one felt the banality of the moment so acutely as Walter Lippmann, who covered the hearing as a correspondent for the New Republic, a magazine he had helped create a few months earlier. Here sat the inheritor of the greatest fortune in the world, a man with more responsibility over a larger part of the national economy than any other single person, a living symbol of monopoly capital and labor injustice. “Yet,” to Lippmann’s disgust, “he talked about himself on the commonplace moral assumptions of a small business man.” No greater failure of the American system could be comprehended than that this “careful, plodding, essentially uninteresting person” should have his position—unwanted, unearned—thrust upon him. It was an absurd situation from which nobody benefited. “Those who rule and have no love of power suffer much,” thought Lippmann. “John D. Rockefeller, Jr., is one of these, I think, and he is indeed a victim.”

After the ordeal was over, Junior was descending the staircase when he suddenly paused. A white-haired woman in glasses stood in his path. It was Mother Jones. The guards urged him forward, but he stopped and held out his hand to her.

“We ought to be working together,” he said.

“Come out to Colorado with me,” she replied, “and I’ll show you what we can do.”

IN FACT, HE had long planned to visit the coalfields. During the strike, a trip to Colorado would have been inflammatory and detrimental to the company’s position. But even as he suffered through the outbreak of criticism that accompanied the revelations of his publicity efforts, he was simultaneously working on a way to bring meaningful reforms to the mine employees.

Increasingly aware that some of Ivy Lee’s “advice had been unsound on several occasions,” Junior had come under the tutelage of William Lyon Mackenzie King. The former minister of labor for Canada, King had been brought in to help with the project of industrial relations—just as Lee had been hired to conduct public relations. Believing that Colorado Fuel & Iron had to offer its men more of a say in their own affairs, he suggested the creation of a grievance board where workers could seek a hearing for their complaints. While it did not go so far as to grant workers the right to unionize, it still showed a willingness to compromise that would never have been sanctioned by Bowers and the other operators. At the center of the idea was Junior’s belief that personal connection between workers and bosses could overcome the perception of differences. “The hope of establishing confidence between employers and employed,” he wrote to the president of Colorado Fuel & Iron, “will lie more in the known willingness on the part of each to confer frankly with the other than in anything else.” Officially called “the Plan of Representation and Agreement,” it would come to be known as the “Rockefeller Plan,” and, in September 1915, Junior traveled to Colorado to convince both sides to ratify it.

For three weeks he toured mines, camps, and factories, speaking personally with hundreds of employees, sharing their meals, and even going so far as to don overalls and wield a pick in one of the coal shafts. “He did not dig very much,” a reporter for the Times noted. “The miners grinned, but Mr. Rockefeller hacked away and laughed as the black lumps began to rattle down.” He distributed prize money to the homes with the nicest gardens and offered to reimburse a community that wanted to construct a bandstand. At one meeting he suggested pushing the chairs to the side of the hall and then organized an impromptu dance, fox-trotting with each of the miners’ wives in turn.

There had been no way to predict how the workers would receive him. Ambling through the camps and mingling with the men, Rockefeller exposed himself to reprisal. Any person in Colorado who claimed a grudge—and thousands might have done so—could have enacted a just revenge. It had been a risk to stride into the center of what had been a war zone. Senior had tried, unsuccessfully, to convince his son’s secretary to carry a pistol with him for protection. But Junior encountered only warmth and generosity. The miners were in the mood to forgive, and with employment so precarious, it would have been foolhardy to make a demonstration. Few of the active strikers had been rehired, so the employees he met were almost certainly not the same people who had actually inhabited the Ludlow colony. But it was also true that Junior, with his modest and self-effacing manners, chose this occasion to show his best self. “Had Mr. Rockefeller not been the man he is,” King wrote to Abby during the trip, “and had he not met his fellowmen of all classes in the manner he did … some situation would almost have certainly presented itself which would have made the tour of the coal fields as disastrous in its effect as, owing to his wonderful adaptability, it has been triumphant.”

ROCKEFELLER WINS OVER MINERS WHO FORGET TRAGEDY AT LUDLOW, a Denver Post headline exulted. ROCKEFELLER TURNS HATE OF MINERS TO LOVE, reported the Chicago Tribune. “Enmity,” wrote King, “has been changed into good-will; bitterness into trust; and resentful recollections into cherished memories.” In Pueblo on October 2, Junior formally introduced his plan of management, which, according to the press, granted “practically every point which any labor union ever asked, with the one exception of recognition of the union.” To illustrate his vision of the ideal corporation, Junior spilled some coins onto a small table. Each leg represented one of the four parties that made up a business: stockholders, directors, officers, workers. Because the legs were represented evenly, the tabletop was level and the money piled up. “Again,” he explained, “you will notice that this table is square. And every corporation to be successful must be on the square—absolutely a square deal for every one of the four parties, and for every man in each of the four parties.” When the vote was tallied, an overwhelming majority of the employees, and all the directors, had opted for the Rockefeller Plan.

“I cannot but feel,” King confided to Abby at the end of the three weeks he had traveled with her husband, “that this visit is epoch-making in his own life, as it will also prove epoch-making in the industrial history of this continent.”

* * *

LESS THAN ONE month after the Lexington Avenue explosion, on August 1, 1914, Commissioner Arthur Woods announced a major shake-up of the police department. Using the bomb to justify his claims that the city required a real secret service, he announced the creation of a new force: the anarchist and bomb squad. Finally, he was able to complete the task Commissioner Bingham had begun a decade earlier. Following his mentor’s opinions, he explained to the city that the infiltration and surveillance of dissident organizations would be a powerful deterrent against future terror threats. The unit went to work immediately. Officers of “various nationalities” took up “residence among the various groups” of radicals and set out to “secure evidence against anarchists and followers of the I.W.W.” They employed the most modern techniques, as well as elaborate disguises and subterfuges. Anything was acceptable if it allowed the secret operators to insinuate themselves among their dangerous quarry. “Detectives were carefully instructed how to act,” since everyone knew that “it was the custom of the I.W.W. and anarchists to investigate carefully all new members.”

Despite this specialized instruction, the new division was unsuccessful at preventing further anarchist attacks. As it happened, the most virulent bombing campaign in the city’s history occurred in the squad’s first years. On October 13, bombs targeted St. Patrick’s Cathedral and St. Alphonsus’ Church, where Tannenbaum had been arrested. On November 11, the anniversary of the Haymarket executions, unknown bombers attacked the Bronx County Courthouse. A few days later, a bomb was disabled before it exploded underneath a seat in the Tombs police court: The presiding magistrate was the same judge who had sentenced Tannenbaum to a year in prison. Despite the apparent links to radical causes and the Anarchist Squad’s relentless efforts, no one was ever arrested for any of these attacks.

The secret police made their impact in other ways. New York’s radicals found themselves targeted by “mosquito spies” and provocateurs. Ever since Caron’s death, Mother Earth complained, “the Anarchist, the I.W.W. groups and the Ferrer Center have been infested by mesmerists in search of fit subjects.” The school and community meeting place at the Ferrer center, plagued by informants, relocated from 107th Street to a rural farm in Stelton, New Jersey. And for those who stayed, a spreading distrust made even simple activities difficult. Undercover detectives would sidle into peaceful assemblies and declaim violent speeches advocating the use “of violence, bombs, and dynamite,” trying to instigate some attack that could then be thwarted. For the most part, their presence was little more than an annoyance for the veteran agitators. “Naturally they dared not approach experienced people,” Emma Goldman wrote. “But when they were told to get out, they turned to the young.” One member of the bomb squad convinced two youths, Carmine Carbone and Frank Abarno, to detonate a bomb in St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The provocateur planned the attack, provided the explosives, and, according to the radicals, even lit the fuse, only to have other detectives race in and “prevent” the attack. Despite the obviousness of the frame-up, a judge sentenced the two defendants to six to twelve years in Sing Sing.

Other infiltrators inadvertently revealed themselves. The anarchists discovered one when he failed to stamp a report, and his letter, addressed to the Burns Detective Agency, was returned to the Ferrer Center. Another gave himself away when his dentist noticed a revolver under his jacket. A third agent, Dave Sullivan, had served a prison sentence during the Free Silence agitation and had gone further into the radicals’ confidence by becoming Becky Edelsohn’s lover. He was discovered only after his outraged wife finally caught on and exposed him. Despite the clumsiness of these attempts, at least one spy did manage to inflict actual damage. Donald Vose, the son of one of Goldman’s closest friends, had lived in the Mother Earth offices for most of 1914. Unbeknownst to the anarchists, he was a paid informant of the Burns detective agency, and information he gleaned from their conversations allowed him to lead police to arrest two suspects who were still wanted from the 1910 Los Angeles Times bombing case.

Even as the conflict with radicals intensified, police investigators found themselves distracted by a new and greater threat. In spite of Mayor Mitchel’s pleas, it was proving impossible for New Yorkers to avoid entirely the repercussions of the Great War in Europe. By 1915, panicky reports were already warning of German saboteurs in the city. Police prepared for draft riots. “Plans have been laid by the Commissioner for almost any emergency that might arise out of alien plots or the exigencies of war,” Edward Mott Woolley informed the readers of McClure’s. “Every block in the city has at least one citizen who is a special agent of the police, and whose duty it is to communicate instantly any evidence of danger from enemies.” The Anarchist Squad became the neutrality squad. Just as the old Italian detectives had tried to find links between radicals and the Black Hand, the new division came to understand its various enemies as part of one single conspiracy. Inspector Thomas J. Tunney, the unit’s chief, told his men to divide their attention between “the Prussian, the Bolshevik, and the Anarchist.”

The breath of the Hun.

WHILE OVERSEEING THESE infiltrations, Commissioner Woods continued his public agitation for free speech. During 1916, when a traction strike in the city brought streetcars, elevated trains, and subways to a halt, he insisted that the police had a responsibility only to keep the peace, and that the department would not allow itself to serve as hired muscle for corporate bosses. “The question [of] who won the strike” did not interest the police, Woods wrote: “Their duty, and their sole duty, was to maintain order, to protect life and property, to ensure to all concerned—the companies, the workers, the public—the enjoyment of their full legal rights.” As he had done two years earlier, and in strikingly similar language, the commissioner stressed the sanctity of free speech; “there was no law to prevent one man from talking to another on the street,” he wrote. Only if strikers “became disorderly the police would take action.”

As usual, however, Woods’s defense of constitutional rights reflected just one aspect of his method. Two months before the transit strike, he had testified before state legislators in defense of his use of wiretaps in criminal investigations. “Eavesdropping—the most objectionable sort of thing is eavesdropping,” he admitted. “We all object to it, we all revolt at the very idea of it.” And yet, he argued, it was absolutely necessary in certain cases. The politicians worried that surveillance might accidentally be used against respectable citizens. But Woods said that he personally decided when the technique could be used, and, of course, he was confident in his own discretion. When it came to more abstract concerns about civil liberties, he was simply dismissive. “There is altogether too much sappy talk about the rights of the crook,” he scoffed. “He is a crook. He is an outlaw. He defies what has been put down as what shall be done and what shall not be done by the great body of law-abiding citizens. Where does his right come in?”

* * *

IN ONES AND TWOS, by elevated train and limousine, the gathering massed along the piers at Fifty-third Street along the East River on the morning of March 10, 1915. Chatting and laughing, the good-humored crowd kept its attention focused on the water. Shortly after nine a.m., their eyes were drawn to an approaching ferry; then, as the boat drew nearer, someone spotted a thin figure on the upper deck, madly waving a handkerchief. “It’s Frank!” they shouted. “It’s Frank!” As he stepped onshore, looking pale and, thanks to his spectacles, older than they remembered him, the welcoming committee thrust a bouquet of red carnations in his hand. After minutes of hugs and exclamations, they all departed for a celebratory breakfast; no one had noticed the member of the Anarchist Squad who had been lurking nearby the entire time.

“Tannenbaum was, I guess, a rather unruly prisoner,” Lincoln Steffens reluctantly conceded. In total, he had served three stints in the cooler and had spent his final two months in solitary confinement. At a reception in the Mother Earth offices on his first evening of freedom, Frank described for the reporters some of the abuses he had seen. “For monumental ignorance allow me to commend Warden Hayes,” he said. Not only had he overseen beatings and starvations; the tyrant of Blackwell’s Island had proven to be more or less illiterate, at least in his role as censor. He had banned Goethe’s Faust, as well as various works of bourgeois history and the Nation magazine, while obliviously allowing Frank to read the entire Kropotkin library in his cell. “I see no reason why any remarks of Tannenbaum should call for comment from me,” Commissioner Davis had indignantly replied when reporters contacted her for a response, “and I am not going to enter into any controversy with Tannenbaum.”

But she was mistaken. Frank went to work for the Masses magazine; in the summer of 1915 he published a series of exposés revealing the worst of what he had seen. Spurred to outrage, the state launched an investigation into conditions on the island. Warden Hayes testified to turning pressure hoses onto inmates and forcing them to sleep on the soaked floor, and he seemed surprised by the idea that healthy prisoners should be separated from those with syphilis or tuberculosis. The cooler he defended as a necessary evil. When Commissioner Davis was called in for questioning, she scolded the examiners and questioned their expertise, confronting them face-to-face, refusing to remain seated. Asked if she agreed with the warden’s tactics of shattering an inmate through punishment, she replied, “Not until the prisoner’s spirit is broken, but until he behaves.”

Davis defended her subordinate’s integrity, though she admitted his ideas of penology had not quite kept pace with the times. The damage was done, however, and a week after she testified, the Department of Correction announced that Warden Hayes was out: He had been put on leave through the end of the year, at which point he would retire. On Blackwell’s Island, the prisoners gave three cheers for Tannenbaum. “The state prison commission has found Warden Hayes unfit for his position,” the Masses cheered. “By how many months do we anticipate the findings of another commission when we say that Commissioner Davis is unfit for hers?”

TANNENBAUM’S COMRADES IN the Industrial Workers of the World, who believed that prison improvements were a distraction from the real work of factory struggle, worried that his success as a reformer might dull his agitations. “Am glad you are ready for work on ‘The Masses,’” Jane Roulston wrote soon after his release, “but am sorry you have no time to affiliate with the I.W.W.” Frank retained fond memories of his time with the One Big Union. “The I.W.W. that I knew I shall always look back upon with the greatest reverence,” he would later write. “Nowhere have I found that idealism, that love of one’s kind, that social mindedness and sincerity.” In his first week of freedom he spoke to a rally in Union Square. But even though conditions in the city remained desperate—unemployment and homelessness had only increased since the previous year—the context had changed. Thanks to his agitations, there were now jobless commissions and church-organized bureaus for those who were out of work. A whole infrastructure of relief was beginning to emerge. “That may not be much to accomplish,” Frank modestly conceded, “but it at least means that a little bit of conscience has been awakened.”

Tannenbaum’s time as a revolutionist was over; still smarting from a feeling of intellectual inadequacy, his consuming interest was to further his education. Most of his entire first day of freedom was spent on the campus of Columbia University, in Morningside Heights in northern Manhattan. With the assistance of friends he was allowed to pass the “character test,” and he enrolled for classes in the summer of 1915. Not surprisingly, his former associates were aghast. “I hear you intend going to Columbia,” wrote Alexander Berkman, who was in San Francisco. “Of course, advice, is never in place, but I’m sure you are going to waste several years in learning things mostly not worth knowing, partly that ‘ain’t so’, + a small balance of which worth knowing you could acquire more thoroughly with much less expenditure of time, effort + money. In other words, it’s a relic of ignorance to worship a ‘college education.’“

But Frank ignored all remonstrance. Every morning he woke up at five a.m. to study. Through “work—everlasting plugging,” he managed to make up for the reading he had missed out on and started to catch up with his colleagues. It was a struggle at first. In his first two semesters, he received a D in English composition, a C in German, and a B for various courses in history. The former revolutionist received his best mark—an A—in Business.

* * *

“I THINK YOU have the town with you,” Mayor Mitchel’s secretary wrote to Katharine B. Davis in early August 1914. The commissioner had just quelled the Independence Day prison riots, and she was on her way to resolving Becky Edelsohn’s hunger strike. But within a year most of that support had vanished. Criticism made Davis defensive; it amplified the authoritative tendencies that had already made her despised among her prisoners. Whatever goodwill she retained was eroded by shocking revelations of maltreatment and neglect within the city’s jails. Tannenbaum’s investigation had exposed the worst of Blackwell’s Island, the Department of Health condemned conditions in the Tombs, and the state Board of Charities did the same for Hart Island. Having begun her tenure with such headstrong ambition, Davis now spoke of the necessity of gradualism. “I am, I assert, a conservative radical,” she explained. “Changes have to be made slowly. I have tried to conduct an educational campaign, and I have been reorganizing slowly … I have to move slowly.”

Not all of these failures were hers alone. Like her colleagues in the administration, she had come to her post with advanced ideas about social science but scant experience in governing. Her main problem had nothing to do with temperament, caution, or conservatism: It was a matter of money. All the grandiose visions of the Mitchel government’s earliest days had been concocted without the slightest care for appropriations and budgeting. The jails in particular needed enormous improvements, and most should have just been demolished. Davis had pleaded for increased funding. “I shouted until I was hoarse,” she explained. “I know how to economize, but I can’t do the impossible. It is the same proposition that Charities Commissioner Kingsbury is up against. The population we care for has increased 50 per cent. and the appropriation 4 per cent.”

But public opinion, outraged by the stories of abuse, focused its anger on Davis herself. Her sex only accelerated her fall. At the time of her appointment, most people had approved of the idea of a female prison commissioner. Now the doubters appeared. “Admirable women, put in places of authority and long retained there,” theorized the editors at Life, “are often seen to cripple the lives they dominate by excessive exercise of control. They get over-development of the will, scare off the people who ought to work with them and come lonely to saddened ends.” Militant feminists were skeptical, too, but for different reasons. “Women,” argued Margaret Sanger, “have been too ready to admire other women who, with inflated ideas of self-importance, are willing to degrade themselves and their sex by assuming the barbaric posts that decent men are giving up—in short by becoming detectives, policewomen and commissioners of correction. Let us proclaim such women as traitors and enemies of the working class!”

In the end, the prediction by the Masses about Davis’s imminent removal proved accurate. In December 1915 she resigned as commissioner of correction and took a new position as the head of the newly created Board of Parole. Press releases once again lauded her as the “best-fitted person” for the job. And Mayor Mitchel supported her to the last. But the tenure of the first woman to hold a cabinet post in a New York City administration had ended in failure and controversy after only two years.

* * *

JOHN ADAMS KINGSBURY had been a perpetual headache to the mayor, his Department of Charities “the storm centre” of the administration. Sure of his ideas, the commissioner had scythed the malefactors and wastrels from his jurisdiction, cutting costs, improving care—and amassing enemies. “There was this fatal streak in him of no compromise,” thought Frances Perkins. Another member of the government recalled how every one of his manic initiatives created “some new little gang of people that had their knives out for him.” But no confrontation in his tenure had proven so damaging as his clash with the Sisters of Mercy.

The city spent millions each year in public subsidies for private orphanages. The Catholic Church was the largest benefactor from these payments, receiving $2.50 a week for each of the twenty-three thousand children enrolled in its parochial schools and orphanages. In former years, Tammany administrations had disbursed this largesse without much in the way of accounting and oversight. Kingsbury changed that. Scrutinizing every dormitory, bathroom, and kitchen, he discovered the inevitable disgrace: “Beds were alive with vermin,” he reported to the mayor at the end of 1914; “antiquated methods of punishment prevailed … the children were given little else save religious instruction.” In one institution, two hundred children were said to be sharing the same toothbrush and cake of soap. What they had seen, investigators concluded, was “worse than anything in Oliver Twist”.

Although his investigations had not focused solely on Catholic facilities—more than half of the criticized schools had been run by Protestants—the diocese nevertheless detected “a nasty anti-Catholic animus” in the inquiry and responded with a campaign in self-defense. Mitchel was denounced as a betrayer of his own faith; Kingsbury and his fellow social scientists were accused of operating a “highly-organized agency of paganism.” Taking a lesson from the practices of Ivy Lee, hundreds of thousands of pamphlets were printed and distributed on church steps each Sunday after mass. “The Church is from God,” parishioners read. “Modern sociology is not.”

Kingsbury was not patient with impediments. Finding his efforts thwarted, he immediately began to suspect a criminal conspiracy. With the assistance of Commissioner Woods and the consent of the mayor, he took the extreme step of having the police install wiretaps on the telephones of several prominent church spokesmen. When word of this measure inevitably leaked, the officials found themselves denounced everywhere. Civic and religious groups demanded Mitchel’s impeachment; the governor launched an investigation. William Randolph Hearst’s New York American was especially eager to press the assault; “in making this arbitrary and unlawful invasion and incursion upon the privacy of citizens’ homes and businesses,” its editors wrote, the government was “not one bit better morally than any thief who climbs in the window to steal a householder’s papers or money.” The administration—at first—denied any knowledge of the affair, then it clumsily attempted to destroy the evidence. But in May 1916 a Brooklyn grand jury indicted Kingsbury and considered doing the same for others. “If, as it does appear,” the court declared, “Mayor Mitchel and Police Commissioner Woods approved of the conduct of those responsible for the tapping of the wires … they merit severe condemnation.”

After more than a year of controversy, Kingsbury was acquitted. But to his—and the mayor’s—list of enemies had been added many of the million Catholic voters who lived in New York City.

* * *

ALEXANDER BERKMAN WAS restless. He had hardly left New York in eight years, and with police spies everywhere, the city was less hospitable than ever before. Toward the end of 1914, he began to plan a crosscountry lecture tour. As the date to leave approached, the prospect shone brighter. “Too long in one place, at the same kind of work, has a tendency to stale one,” he wrote. “Again, living many years in New York one is apt to regard the Metropolis as a criterion of the whole country, in point of general conditions and revolutionary activity—which is far from correct.” Then, on the night before departure, his farewell party was interrupted by the cops. Berkman was arrested and missed his train. “Man proposes, and the police impose,” he wrote good-humoredly; this latest outrage delayed his start by only a single day.

His first stop, Pittsburgh, brought old recollections hurtling back. Twenty-two years had passed since his attack on Frick. A lecture in the city was well attended. But in Homestead, site of the 1892 steel strike, he was depressed to find the workers cowed and dispirited; riddled with informers, they were unwilling, he concluded, to risk their jobs to hear his speech. Elyria, Detroit, Buffalo, Denver: At every destination he faced petty injunctions. Auditorium owners reneged on their contracts; police disturbed the meetings. Even when he was allowed to talk, the results tended to be disappointing. “The poor boy seems to have absolutely no luck with lectures,” Goldman wrote. “He is terribly discouraged, which I can readily understand.” His gloom transmitted itself to his impressions of the country. “Kansas City is depressing: the sky is drab, the air smutty, the streets haunted by emaciated and bedraggled unemployed,” he wrote. “Cleveland, Chicago, Minneapolis, St. Louis—everywhere I find the same situation.” His enthusiasm for travel rapidly diminished. After two months on the road, the city he had escaped with such relief had already been transformed by wistful memory into “dear old Gotham.”

The life of the itinerant missionary did not suit him; he had to be agitating. But somehow anger—the rage that had driven his politics all along—no longer felt appropriate. Sorrow was the only appropriate response to the war and its effects. Just as he had foretold, the governments of every nation had used the conflict as an excuse to persecute its dissidents; the citizenry, in its patriotic fury, had acquiesced to assist in this effort. Lifelong advocates of peace and cooperation now joined the nationalists. Even Kropotkin, the greatest anarchist teacher, had succumbed to the fallacy of ethnocentrism, writing a pamphlet declaring the need for the Slavic Russians to defeat Prussian militarism. Berkman could only take it philosophically. “Time tempers the impatience of Youth,” he wrote. “Slowly, but imperatively, life forces us to learn to conceive of the Social Revolution as something less cataclysmic and mechanical, something more definite and humanly real.”

He was in California during the summer of 1916, editing a magazine he had dubbed the Blast, when a new outrage relieved his stupor. The war was in its second year, and Americans were growing frustrated with neutrality. The Lusitania, which had escaped from New York Harbor in the first days of the conflict, had since been sunk by a German torpedo, costing more than a hundred American lives. A campaign for “Preparedness” found civilians marching and camping out, training themselves for the possibility of fighting. On July 22, a pro-military parade in San Francisco scattered in panic when a bomb, thrown by an unknown hand, detonated in the midst of the crowd, killing eight people and wounding dozens more.

Berkman and Goldman learned about the attack over the telephone, and their initial thought was, “I hope we anarchists will not again be held responsible.” They were. Just like thirty years earlier in Chicago, the government indicted labor leaders for the crime—in this case Thomas Mooney and Warren Billings—ignoring the fact that no evidence linked them to the crime. When a hostile judge ordered Mooney to be executed, Berkman, who was himself facing imminent indictment, fomented national and international opposition. Most crucially, by using his contacts in Russia, he was able to organize street protests in Petrograd and Kronstadt. Word of the demonstrations passed from the American ambassador to Woodrow Wilson, who, mindful of the diplomatic impact on the war, personally requested that the California governor commute Mooney’s sentence to life imprisonment.

That was a small but vital victory—and it was also the last.

* * *

ON APRIL 2, 1917, Washington, D.C., prepared for battle. President Wilson had called the Congress into extraordinary session, and it was widely expected that he would be asking the legislature to ratify a declaration of war. After all the years of hesitation—and a reelection campaign waged on the promise of keeping the United States out of the conflict—he was finally ready to make the dreadful decision. Antiwar groups had mobilized to show their disapproval, assaulting government offices with angry telegrams and sending thousands of delegates to the city. Outside, the Capitol was surrounded by encampments occupied by irate pacifists; inside, “the building swarmed with Secret Service men, Post Office inspectors, and policemen.” Protesters rallied through the streets wearing white armbands and waving streamers that read WE WANT PEACE and KEEP OUT OF WAR. Advocates for women’s suffrage, in an unrelated rally that had been ongoing since January, added their pickets to the general turmoil.

Wilson’s speech was prepared; he was ready, and none could accuse him of taking this step lightly. After the disastrous occupation of Veracruz, he had kept steadfast in refusing to commit American arms to foreign soil. In 1916, he had reluctantly—and only after repeated provocations—agreed to send an expeditionary force into northern Mexico in an unsuccessful attempt to capture the renegade Pancho Villa. Since then, and despite the far greater pressures of the European war, he had dedicated himself to the moral righteousness of neutrality. “There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight,” he had said after a German torpedo sank the Lusitania. “There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right.” Always at the heart of his thinking was the remembrance of those coffins he had seen in New York City. “I have to sleep with my conscience in these matters,” he explained, “and I shall be held responsible for every drop of blood that may be spent.”

Afternoon turned to evening, but the streets remained too chaotic for the president to appear. Onlookers jeered as police and army reservists were called in to clear a thousand pacifists from the stairs on the eastern side of the Capitol building. By nightfall, peace had finally been restored. The remaining spectators applauded as two troops of cavalry, their “sabres glittering under the arc lights,” cantered into the plaza. Behind them, the president’s automobile stopped by the entrance. Flanked by Secret Service agents and clutching a few sheets of typewritten notes, Woodrow Wilson strode inside. The senators, Supreme Court justices, and members of the diplomatic corps had only just found their seats in the chamber of the House of Representatives when the speaker rose to announce, “The President of the United States.” Everyone stood again; the congressmen “not only cheered, but yelled” an ovation unlike any he had ever before received in Washington.

Wilson held his speech in both hands, concentrating on the words and not looking up from the pages. He began with a litany of German misdeeds, starting with the invasion of Belgium and ending with the recent belligerency on the high seas. “He spoke slowly at first,” a reporter observed, “then faster than usual. His voice was clear and grew stronger as he proceeded.” He built his case methodically, gradually approaching the decisive point. There were no interruptions; “the close attention deepened into a breathless silence, so painfully intense that it seemed almost audible.” Finally, he came to it. “With a profound sense of the solemn and even tragical character of the step I am taking,” he asked Congress to “formally accept the status of belligerent which has been thrust upon it.”

Further on, nearly at the end of his oration, Wilson added one last justification for the choice that he had made. “The world,” he explained, “must be made safe for democracy.” This remark almost passed without notice. But one senator realized it was the keynote of the entire address. Alone, he clapped his hands—“gravely, emphatically”—and then the ovation spread. “One after another,” noted a Times reporter, others “followed his lead until the whole host broke forth in a great uproar of applause.”

WORD OF THE president’s decision began spreading through New York during the midst of the evening’s entertainments. At the Metropolitan Opera, the audience stood throughout the intermission to sing the anthem and cheer the armed forces. News of impending war flashed onto the moving-picture screen at the Rialto, on Forty-second Street, and at other cinemas throughout the city. Crowds streamed from the cabarets and theaters, crying “Hurrah for Wilson!” and “Down with the Kaiser!” In the streets, vendors did a roaring business in flags; noisy impromptu parades materialized on Fifth Avenue and Broadway.

Woodrow Wilson addressing Congress.

No special announcements were made at Lüchow’s or the Hofbrau Haus, two of New York’s leading German restaurants. In the midst of the celebrations, socialists who spoke out against the conflict were beaten and arrested. At Rector’s, the orchestra broke into “The Star-Spangled Banner” and the patrons rose to their feet. When diners at one table refused to stand, they were attacked and had to be rescued by the waiters. For these residents of the city, it was not the part of Wilson’s speech about making the world safe for democracy that seemed to be the central issue, but another phrase that had gone largely unremarked upon. “If there should be disloyalty,” the president had told Congress, “it will be dealt with with a firm hand of stern repression.”

Having entered the war, the United States rushed to outdo its European peers in the silencing of dissent. In the months following Wilson’s declaration, tyrannies of every degree and pitch undid the progress of decades of progressive agitations. Citizen vigilance committees instigated neighborly mob justice. Pacifists were attacked and jailed. The New York Tribune offered its readers a weekly column entitled “Who’s Who Against America,” which spotlighted William Randolph Hearst, Victor Berger, the entire state of Wisconsin, and anyone else who publicly doubted the virtues of the war. The Espionage and Sedition acts criminalized “disloyal, profane, scurrilous or abusive language about the form of government of the U.S. or the constitution of the U.S.,” effectively ending free speech across the nation. Radical publications were banned from the mails, with Mother Earth and the Blast atop the list. Under the new statutes, almost every word spoken by anarchists, socialists, or progressives during the previous thirty years—as well as most of the works of Lincoln, Thoreau, and any number of quintessentially American thinkers—now constituted a criminal felony. “They give you ninety days for quoting the Declaration of Independence,” said Max Eastman, editor of the Masses, “six months for quoting the Bible, and pretty soon somebody is going to get a life sentence for quoting Woodrow Wilson in the wrong connection.”

Public figures of every stripe had to reexamine their beliefs.

Upton and Craig Sinclair, who had fled Manhattan soon after Caron’s death, were now living in a ramshackle house in Pasadena, California. Through 1916, they had collaborated on his new novel, King Coal, based on the Colorado strike. The book appeared in September 1917 and proved to be another commercial failure. By then the United States had entered into war. Unlike most socialists, Sinclair enthusiastically supported the president’s crusade against German militarism, a position that forced him to split from the party he had championed for the previous decade. Since radical publications, including the Call and Appeal to Reason, had been the only dependable outlet for his writings, he was left with no way to share his thoughts with the public. This was not acceptable, so he founded a journal of his own, Upton Sinclair’s magazine. But despite his prowar stance, his troubles continued even then. Citing his association with Caron, the post office refused to grant him a second-class mailing permit.

Walter Lippmann had demurred, back in 1914, when Sinclair had tried to recruit him for the Free Silence League. “A man has to make up his mind what his job is and stick to that,” he wrote. “I know that agitation isn’t my job.” Three years later, with the country in the conflict, the twenty-seven-year-old found another role that would not suit his liking: that of soldier. “I’m convinced,” he wrote to the secretary of war, “that I can serve my bit much more effectively than as a private in the new armies.” Bored with his work at the New Republic and eager to be nearer to the center of power, he lobbied for and received an official post at the War Department. From the heights, he then watched as repressions struck at his former associates. As usual, he viewed the matter dispassionately. “So far as I am concerned,” he wrote to Colonel Edward House, adviser to the president, “I have no doctrinaire belief in free speech. In the interest of the war it is necessary to sacrifice some of it.”

ON JUNE 15, 1917, New York City police arrested Berkman and Goldman in their Harlem offices. Even as repressions mounted, the two anarchists had never paused in their work, founding the No Conscription League and continually speaking publicly against the war. At their trial, they presented their own defense, turning the proceedings into an indictment of the persecutions that the war paranoia had engendered in America. Neither expected to be acquitted, and in fact they were both given long sentences in federal prison, to be followed by deportation. Their ordeal would be imposed on others again and again in the following months. Prosecutors had ceased to make any distinction between the varied gradations of protest, classifying all dissenters as “German auxiliaries in the United States.” Wobblies were pilloried and attacked; the Times editors demanded that the Ferrer School curriculum be scrutinized. Big Bill Haywood was jailed. Eugene V. Debs, the Socialist Party’s presidential candidate in 1912, was arrested for stating the obvious fact that Wall Street had benefited from the war.

Berkman spent the next two years in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary; Goldman was held in Jefferson City, Missouri. Beyond the walls, the Russian revolution, in November 1917, offered a tantalizing hope that all their efforts had not been wasted. “The Boylsheviki alone,” Berkman wrote in Mother Earth during the early days of the new regime, “have the faith and strength of actually putting the program of the Social Revolution into operation.” At home, the armistice immediately brought the prewar antagonisms back into view. The conflict between capital and labor reemerged more dramatically than before. The tumultuous year 1919 began with a general strike in Seattle and a police strike in Boston. As May Day approached, a mail bomb exploded in a senator’s house; then thirty-six identical packages, each addressed to a leading government figure, were discovered by a postal worker and defused. In June, dynamite exploded on the front porch of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s Washington townhouse. Gripped by a full-fledged Red Scare, the government instituted vicious retaliations. Palmer ordered a campaign of raids against any radical organization that was still standing; thousands were arrested.

Alexander Berkman in 1919.

On October 1, 1919, Berkman was released from prison and returned to New York City. For the next two months, he and Goldman joined together in a final agitation, but this time it was their own rights they were defending. Federal authorities demanded their deportation to Russia, and at the height of antiradical feeling, there was little they could do to fight it. “Now reaction is in full swing,” wrote Berkman. “The actual reality is even darker than our worst predictions. Liberty is dead, and white terror on top dominates the country. Free speech is a thing of the past.” After thirty years of living and working in the city, the anarchists could not even find a hall to rent, or a single benefactor to support them.

For most of December, Berkman was held in a cell on Ellis Island while immigration officials made their arrangements. Then, on the twenty-first, he and Goldman, as well as about 250 other undesirables, were hustled down to the Buford, a leaky transport ship that would carry them to Russia. The press dubbed her the “Soviet Ark.” Before dawn their journey began; the vessel steamed past the Statue of Liberty and out toward the lower bay. “Slowly the big city receded, wrapped in a milky veil,” wrote Berkman of his last sight of dear old Gotham. “The tall skyscrapers, their outlines dimmed, looked like fairy castles lit by winking stars and then all was swallowed in the distance.”

During the final rush of events, when he had been hurried from prison to prison with little chance to gather his things or make arrangements, there had at least been one satisfying moment. In the midst of his farewell gala in Chicago, a clutch of reporters had burst in with startling news: Henry Clay Frick, the ancient nemesis, had died. Pressed for a quote, Berkman replied, “Just say he was deported by God.”

* * *

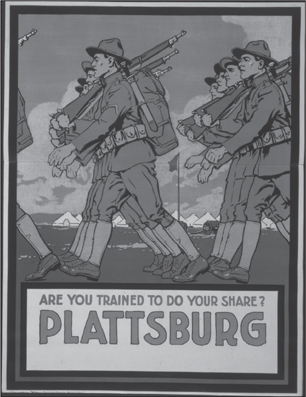

TWO PAIRS OF boots, medium-weight socks, olive drab breeches and shirts, a pair of leggings and a campaign hat: Mayor Mitchel had the clerk wrap these purchases before departing for a month-long vacation in Plattsburg, in the Adirondack Mountains near the Canadian border. On August 9, 1915, he arrived and received the rest of his gear—canteen, poncho, pup tent—while the first of more than a thousand others joined him. Like the mayor, they were not quite young, of the gentry—lawyers, brokers, bankers, journalists, college men, “our kind of people”—and all toting the same unlikely equipage.

Although he had urged neutrality on the citizens of New York City, the mayor had not personally been satisfied by that policy for long. In 1914 he had been frustrated by Wilson’s vacillation toward Mexico, but standing aside during the Great War was proving to be far worse. There was something dishonorable in remaining aloof in a time of crisis. With his close proximity to Wall Street, which had loaned millions to the allies, Mitchel understood that each day found American interests more tightly linked to the fortunes of England and France. He was certain that the nation would be drawn into the struggle, and yet the pretense of impartiality kept Wilson from taking the necessary measures. New York’s defenses were a travesty, but the national government declined to invest in their improvement; the army was undermanned and ill equipped, but nothing was done about it—all because the president, looking ahead to his postwar role as peacemaker, feared any step that could “destroy the calm spirit necessary to the rescue of the world from a spell of madness.”

So Mitchel went to Plattsburg for a month of army drills to publicize the need for universal military training, to urge preparedness on an unwilling president, and, most of all, to prove his mettle to himself. Reveille was 5:45 a.m., followed by calisthenics and maneuvers that lasted till evening. The schedule featured a nine-day hike, which the privates undertook while carrying forty-two pounds of gear on their backs. Arthur Woods was present, along with forty of his police officers, and when the mayor bested them all in a riflery competition, the whole country heard about it. Newspaper photographers captured every blister and jumping jack, publicizing the activities of the gentlemen soldiers—and annoying the president with every story. “We are having a thoroughly enjoyable and I believe a thoroughly useful time of it here,” Mitchel wrote to a colleague in the city. “The spirit of the camp is fine, and all of us believe that the experiment is going to prove thoroughly worth while.”

By the time New York’s 1917 municipal election approached, Wilson had abandoned what the mayor had come to see as a “painful neutrality,” and the nation was fully engaged in wartime exertions. Mitchel pined to go to France with the army; he “chafed under the responsibility of his office because it prevented him from enlisting.” Four years of political service had sapped his health; with a salary that hardly covered his expenses, he was in financial trouble as well, and his work had forced him to turn down several lucrative positions. No reform mayor had ever won reelection against Tammany Hall, and Mitchel’s own chances were hardly certain. Only the thought of what Tammany boss Charles Murphy and his chosen candidate, John Hylan, would do to the metropolis kept him from abandoning politics altogether. Finally, picturing his office as a kind of “Western front” in the fight against corruption—and himself “as a good soldier”—he realized there was no choice but to go over the top once more.

Once again, as in 1913, all of America awaited the result. “The whole Nation has an interest in the New York City election which it feels in no other municipal contest,” editors at the World’s Work explained. “This is not only because New York is our largest city … but because it has for a generation symbolized all that is worst and also all that is best in American local government.” The boy mayor transformed himself into the fighting mayor; campaign posters featured him in his Plattsburg khakis with the motto A VOTE FOR MAYOR MITCHEL IS A VOTE FOR THE U.S.A. He made loyalty and patriotism the center of his platform, promising to “make the fight against Hearst, Hylan, and the Hohenzollerns,” as well as anyone else “who raise their heads to spit venom at those who have taken a strong, active stand with America against Germany.” Trying to court an electorate that was largely of Irish and German descent, it was a disastrous strategy. President Wilson, recalling the mayor’s criticism of his neutrality stance, refused to endorse him. After the uproar over the orphanages, Catholic voters were already his implacable enemies—during the campaign, opponents referred to Mitchel as the “ear-at-the-telephone candidate” in reference to the wiretapping scandal—and his association with the elite soldiery of the Plattsburg camp allowed Tammany spokesmen to accuse him of being a silk-stocking leader who had ceded “control of the city to the Rockefeller and the Morgan interests in Wall Street.”

In 1913, John Purroy Mitchel had been elected mayor with the largest plurality in the history of Greater New York. Four years later, he was defeated by an even greater margin. Though it had spent more than a million dollars on the campaign—an unprecedented sum, raised mostly in large contributions from rich donors—Fusion earned less than half of the votes it had received in the previous election. John Hylan’s victory was crushing. Mitchel had only avoided the ultimate ignominy of finishing behind the Socialist Party candidate by a few thousand votes. Tammany Hall, which reformers had once thought beaten, now mocked their efforts, returning to power as if nothing had changed. “We have had,” the new mayor said to his constituents, “all the reform that we want in this city for some time to come.”

There were several explanations for Mitchel’s failure: He had barely campaigned, and had never been able to connect personally with his constituents. But the most important objection to him was his insistence on extending the administration into the private lives of the city’s residents. They had never asked for the mayor’s guidance. They did not want to be studied and tested at the Municipal Lodging House. They resented having their saloons shut down at one a.m. while the cabarets stayed open till dawn. They did not want to be told how to clean their homes, or worship, or raise their children. “The humbler people of New York revolted against the consequences to themselves of government by capable and disinterested experts,” the New Republic concluded after the election. “Mr. Mitchel’s downfall was greeted by a wild outburst of popular enthusiasm on the East Side. It was interpreted as the overthrow of an autocracy of experts which interfered egregiously and unnecessarily with the customs and the privacies of the common people.”

Eager as the voters were to have him gone, their relief hardly matched his own impatience to depart. Mitchel had campaigned only out of a sense of duty, and now his one ambition was to get himself to the fighting lines in France. Citing his Plattsburg training as qualification, he applied for an officer’s commission to every branch he could think of—infantry, artillery, cavalry. All turned him down. He even considered enrolling as a private soldier in the army. The War Department tenaciously blocked his appointment: President Wilson was taking his revenge. With all other options exhausted, Mitchel had no choice but to accept an invitation to join the air service. A thirty-eight-year-old mayor was still youthful, but a pilot trainee at that age was already past his peak. Friends worried about how the competitive enlistee would react to the sudden reversal. “Don’t break your silly neck trying to be young,” cautioned Frank Polk, the former corporation counsel who had been shot in April 1914. The air service lacked the cachet of the older military divisions. Worst of all, it meant months of preparation before he could go overseas. But it was the only route to combat. “Isn’t it a damnable style of uniform?” Mitchel said, sighing, as he gazed in the mirror at the airman’s costume he had purchased from Brooks Brothers. “Ugly and uncomfortable.”

Mitchel in uniform.

In February 1918, he and Olive journeyed to an airfield near San Diego, where Mitchel had been sent for his primary flying course. He approached his first takeoff with trepidation, exuding a fatalistic sense of “resolute courage without cheering hope.” His early ascents were accompanied by an instructor; then he began to solo. Occasionally he would experience bouts of nausea or a migraine in the air, but otherwise it was not so terrible. “The thing really goes much better than I had expected,” he reported. “If you don’t hurry, and keep your head,” he wrote, reassuringly, to his mother, “there is practically no danger in this business of learning to fly as they teach it here.” By April, he had graduated from basic flight to stunt work. Reporters watched in amazement as he “successfully executed the side slip, full loop, half loop, Immelmann turn, and tail spin.” With increasing confidence, he looked forward to the pending opportunity to prove himself in battle. “At all events,” he wrote to a friend in May, “flying is really pretty good fun and as I have more or less unexpectedly lived through the initial stages I believe I am now likely to be preserved for the Hun.”

With a pilot’s degree in hand, Mitchel could brook no more delays. He expected orders imminently that would send him overseas. But days, and then weeks, passed. “I thought they wanted flyers,” he complained, “but apparently killing time is the prime objective. Inscrutable are the ways of military administration.” In the meantime, he had the galling experience of seeing his former subordinates all engaged in useful service. Frank Polk had a position at the State Department. Katharine Davis was with the War Department, coordinating women’s work. As a colonel in the air service, Arthur Woods now outranked his former chief. But these people all had office jobs. If Mitchel had wanted to remain deskbound, there would have been no difficulty; that, however, was not what he had in mind. “It is not so bad to be lost in the fighting end of the game,” he wrote to his former fire commissioner, “but God protect me from being sunk in the dust of a Bureau at Washington.”

Finally, in mid-June, he received his orders, but they were not the ones he had been counting on. Instead of sending him to France, they directed him to Gerstner Field in Lake Charles, Louisiana, for advanced pursuit training. He hated it from the first. The temperature reached 120 degrees at noontime, with no shade to be found. Suffocating in the heat, Mitchel was stricken by a series of migraines. He and Olive rented a bungalow near the base and he obsessed about her health. “This place is an unmitigated hell,” he wrote in a letter home. “It was a crime to put a field here. It is a crime to keep men in such a climate.” Hurricanes, malaria, and dysentery were a constant threat. Frequent accidents and a dissolute atmosphere had lowered morale; the officers’ mess was deep in debt, and instructors verged on nervous collapse. Mitchel flew thirty-three times at the field, logging more than twenty-three hours in the air. Despite illness and a growing sense of foreboding, he tried to keep focused on his goals. “If I live through the next two weeks of acrobatic flying,” he wrote on June 28, halfway through his course, “I guess I can live through most anything.”

MAJOR MITCHEL REPORTED to the airfield a few minutes after seven a.m. on the morning of July 6, 1918; he had been sick the previous day and had awakened with a headache. He appeared high-strung and mentioned in the mess hall that he did not feel like flying. But when the instructor called his name, he dutifully followed him outside. All the machines had been assigned, so they walked to the center of the landing zone to wait for one to return. The Thomas Morse scouts, lithe biplanes used for advanced training, roared in circles above. As he stared upward at the others, his mood improved; he “laughed and joked when the men in the air made a false move.” One of the officers, a New Yorker, apologized for having voted against him in 1917. “That’s all right,” Mitchel replied, “it’s all over now.”

The ships from the first group started coming down. Mitchel hurried to the nearest one and clambered in, but the instructor called him back: The mechanic had reported it unsuitable for flight. About a hundred yards off they found a second plane, but this one had a malfunctioning engine valve. Then another craft landed nearby; they hurried over as the pilot extricated himself from the cockpit. This one was in good order. Mitchel climbed into the seat and looked over the unfamiliar controls of the scout.

This was only his third time in this type of machine. He had taken two short flights the previous day, and they had not gone well. The first time, he had forgotten to buckle his safety harness. The experience had rattled him, and his second attempt had been nervous and indecisive. Both landings had been “exceptionally poor.” After the previous day’s unpromising start, the other pilots were surprised to see him back in a scout plane the next morning. Actually, they thought most of his attempts were below standard. In their opinion, only his social connections had allowed him to qualify for advanced training. Alternately headstrong and overcautious, “he was not sure of himself when in the air and always seemed to be worried.” Another veteran flyer agreed, saying “he was a bunch of nerves, and nerves are bad things for aviators to have.” Not that Mitchel himself harbored any illusions about his own expertise. Despite investing months in training, he was still trying to find a way to transfer to the army.

The Thomas Morse scout plane.

While a flustered Mitchel was trying to orient himself for takeoff, the instructor was distracting him with final guidelines: Climb to six or seven thousand feet, he shouted, and then execute some glides and spirals in order to get a thorough feel for the craft. Don’t try anything tricky. Mitchel throttled up the 100-horsepower engine and the plane began to skip across the grassy field. He lifted into the air and banked left, rising steeply as he circled the base. It would have taken several spirals before he could achieve the required altitude, but after one single circuit, at about a thousand feet, he turned back, shut off the engine, and attempted to glide to a landing. The unusual movement caught the attention of several mechanics and officers on the ground.

As they watched, the plane dived and then began to plummet. There was a sudden lurch—a “peculiar quick snap” that occurred when a panicking or inexperienced pilot pushed the stick forward with too much force—and a dark form catapulted from the cockpit. With horror, the onlookers realized it was the pilot. For five infinite seconds, the figure writhed uselessly, “struggling and grasping and clutching with his hands in the air.” The body struck and tumbled twenty feet across the earth. John Purroy Mitchel, the former boy mayor of New York City, died on impact. For the second time in two days, he had forgotten to fasten his safety belt.