He was set down as belonging to that odious category of outsiders who hung loosely on the fringes of college life: odd persons going about alone, or in little knots, looking intellectual, or looking dissipated. They were likely to be Jews or radicals or to take drugs; to be musical, theatrical, or religious; sallow or bloated, or imperfectly washed; either too shabby or too well dressed. The tribe of these undesirables was always numerous at Harvard.

—George Santayana, The Last Puritan1

Boston in 1928 had little use for modern art. The latest developments in painting were deemed immoral and vulgar. People viewed them as anarchistic, an affront to sanity and God. Pictures, sculpture, and building styles should be a buffer against the present, not an exaltation of it. Most people longed for the comforts of tradition, the familiar look of tried-and-true styles. There had been such an uproar after the venerable Boston Art Club showed some Picasso drawings and other contemporary European art that all but one member of its Art Committee had been forced to resign in September. The club issued a public statement that it had “purged itself of modernism.”2 A new and more conservative art committee took the helm. Its chairman, Mr. H. Dudley Murphy, understood the tenor of the times far better than his predecessor had. “We have had an exploitation of modernist art at the club,” he told a reporter from the New York World. “You know what I mean, that crazy stuff.… We believe that people are rather tired of this sort of thing.” Murphy gave assurance that people could expect “a definite swing away from extreme modernism to the safer realms of conservatism and ‘sanity in art.’ ”3

The first show under the aegis of Murphy’s committee opened the new art season that October. The Evening Transcript reported that the members had the wisdom to redecorate the galleries with a “mouse-colored velvet” that, unlike the “glaring white barn-like walls” previously in place, made “a background suitable to receive the paintings.”4 Most of those paintings were pleasant if tame exemplars of second-generation American Impressionism. They depicted moonlit pools, bunches of dahlias, and ladies holding parasols. On Joy Street, on Beacon Hill, there was an institution with the promising name of the Twentieth Century Club, but only its name suggested anything streamlined or futuristic. Its exhibitions featured representational canvases of ramshackle New England homesteads, academic sculpture, and maps of Boston alongside sketches of city landmarks. In the commercial galleries one could count on more of the same, or English sporting scenes. Occasionally, a work from the School of Paris might go on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, but John Singer Sargent was considered the master to beat them all. The big shows that November were of Sargent’s drawings and of work by the society portraitist Anders Zorn.

Things were not much more advanced on the other side of the Charles River. In Cambridge at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum, one might from time to time see a work on paper or a reproduction of an oil by Cézanne or Van Gogh, even by Picasso, but no such thing would enter the permanent collection. Edward Waldo Forbes, the director of the Fogg, had in 1911 made a decree that was still largely in effect: “The difficulty is, first, that all modern art is not good, and we wish to maintain a high standard. In having exhibitions of the work of living men we may subject ourselves to various embarrassments.”5

There were, however, three Harvard undergraduates who actually relished such embarrassments. Late in 1928, Lincoln Kirstein, Edward M. M. Warburg, and John Walker HI launched an organization “to exhibit to the public works of living contemporary art whose qualities are still frankly debatable.”6 The three college juniors officially founded their Harvard Society for Contemporary Art at a dinner meeting held on December 12 at Shady Hill, the impressive neo-Classical mansion that had belonged to Harvard’s president, Charles Eliot Norton. Since 1915, Shady Hill had been the residence of Paul Joseph Sachs, who that year had become Edward Forbes’s assistant director at the Fogg, and was now his associate director. Sachs had ascended to a full professorship at Harvard in 1927, and the three young men were all under his guidance.

Both Sachs and Forbes liked the idea of the students supplementing the work being done by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the Fogg by mounting exhibitions of various aspects of modern art and design. The creation of the new organization helped take the pressure off the Fogg’s directors to put their necks in the same noose as the management of the Boston Art Club. Sachs and Forbes agreed to serve on the board of the Harvard Society. They volunteered the services of the Fogg staff to help with the more difficult packing and shipping and to defray some of the insurance costs. The Harvard Society for Contemporary Art was the first organization in the country to devote itself to an ongoing program of changing exhibitions of recent art in all its diversity. The latest photography, Bauhaus design, Mexican realism, and German Expressionism could be seen in bits and pieces elsewhere, but nowhere else was there a conscious effort to present in succession such a range of contemporary expressions. Kirstein, Warburg, and Walker, three privileged college students, managed it all while doing their homework on their laps as they performed guard duty.

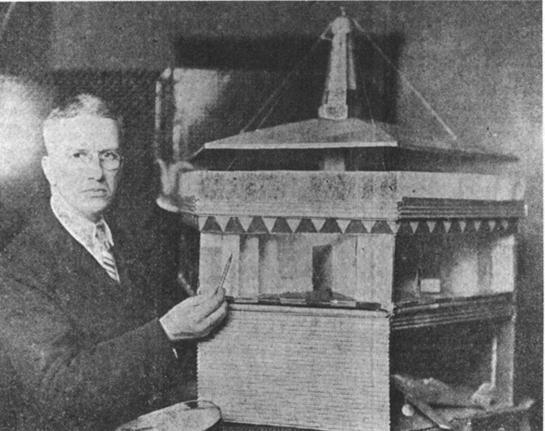

John Walker III, Lincoln Kirstein, and Edward M. M. Warburg, the founders of the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art. (Photo Credit 1.1)

Statement of Purpose and Membership form of the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, 1928. (Photo Credit 1.2)

Shortly after their dinner meeting at Shady Hill, the trio set out to find space for their organization. They rented two rooms on the second floor of the Harvard Cooperative Building at 1400 Massachusetts Avenue. The main floor housed the Harvard Coop, the local emporium for almost anything students might want to buy. The Coop was directly on Harvard Square. Even in those days Harvard Square was a busy urban intersection with noisy bus and subway stops and taxi stands. Although only a five-minute walk across stately Harvard Yard from the Fogg, the location was a step away from the sanctity of the yard and of the quiet lawns at Shady Hill—and into the ordinary, current, urban world.

Kirstein, Warburg, and Walker wanted the setting to be as stark as possible, a statement of newness and now. There was to be no mousy velvet. The idea was to search in directions where others had not looked before, and to stop imitating the past. They painted the walls white and silvered the ceiling with squares of tea paper. For a table they found a massive block of monel—an alloy of nickel and copper—which they rested on four free-standing marble columns that they had picked up in a defunct ice-cream shop. The chairs were the latest streamlined specimens in tubular steel.

They announced plans to mount an exhibition of recent American art and design in a tradition more native than European. To contemplate such a thing in their industrial-looking space was a radical move. A year earlier, Lewis Mumford, in an article on “American Taste” for Harper’s, had described the prevalent disdain for any notion of a new or indigenous national style:

The modern American house can tritely be described as a house that is neither modern nor American. A gallery that today exhibited American taste would be a miscellany of antiquities. The pictures we put on our walls, our cretonnes and brocades and wall papers, our china, our silverware, our furniture, are all copies or close adaptations of things we have found on their historic sites in Europe and America, or, at one remove, in the museums. Meanwhile the art and workmanship of our own day remain unappreciated because they have not yet aged sufficiently to be embraced by the museum.

Mumford asserted that no

period has ever exhibited so much spurious taste as the present one; that is, so much taste derived from hearsay, from imitation, and from the desire to make it appear that mechanical industry has no part in our lives and that we are all blessed with heirlooms testifying to a long and prosperous ancestry in the Old World. Our taste, to put it brutally, is the taste of parvenus.7

The Harvard Society for Contemporary Art would prove the exception.

The founders issued a brochure announcing their plan to show art not yet tested by time, reiterating their seminal notion of exhibiting living art of “frankly debatable” value. Their symbol, in the style of Greek Black Figure vase painting, was a naked, agile, and muscular man appearing euphoric atop a rearing stallion, with another man adjusting the horse’s bridle and bit. This image of high adventure would appear on virtually every invitation and exhibition flyer for the next couple of years. With no explanation or identification beyond the minuscule initials “R.K.,” its authorship and symbolism may have been known to the inner circle, but to the larger audience were ambiguous. “R.K.” stood for Rockwell Kent. Kent, one of Lincoln Kirstein’s favorite designers and book illustrators, had helped boost the new organization by agreeing to do the logo for a nominal fee. The precise meaning of his design was hazy, but its general effect was to suggest action and drama tempered by classic grace. The implications are clear: that the revival of ancient forms and established styles is okay, even desirable, so long as the tone is fresh and the spirit lively.

The brochure included a membership application form. It announced three categories: one for Harvard and Radcliffe students, with annual dues of $2; “contributing” (“$10 or more”), and “sustaining” (“$50 or more”). Kirstein, Warburg, and Walker were listed as members of the “Executive Committee.” There was also an impressive roster of trustees. Besides Edward Waldo Forbes and Paul J. Sachs this included John Nicholas Brown, a wealthy collector of drawings and scion of an old Providence family; Philip Hofer, a bibliophile and collector; Arthur Pope, a distinguished professor of art history; Arthur Sachs, a financier and Paul’s brother; and Felix M. Warburg—Edward’s father, and the only trustee who had not been graduated from Harvard.8 It was a coup for their pioneering undertaking to gain such prominent figures, personally not the least bit inclined toward contemporary art. But here the three students had teamed beautifully. Kirstein was good at formulating ideas, Warburg at communicating them to people who might not have otherwise supported them, Walker at knowing who was who.

The Harvard Society was Kirstein’s invention, and he supplied most of the exhibition themes as well as the rationales behind them. “Impetuous … knowledgeable … overflowing with vitality …”9 is how one of his friends described him. “Brilliant, seductive, violent … but isolated and lonely at the same time”10 is the characterization of another. The tall, broad-shouldered Kirstein was imaginative and articulate, but frequently prickly. With the bearing of a soldier, he generally had a serious and puzzled look on his face. He used his social graces only when the mood suited. He was often cranky and made no effort to mask it. He needed Eddie Warburg and John Walker to deal with the world. The students were promulgating a new gospel, and it took charm to spread it. Eddie Warburg, like Kirstein, also felt great conviction and talked as directly as possible, but he tempered the straight-shooting with a light touch and humor. The dapper, animated Warburg—exotically handsome with his bold features—considered audience response. Kirstein might face his listeners with a misanthropic stare, while Warburg would always come up with a joke. Kirstein had daunting intelligence, but he might ascend a speaker’s platform with the glowering look of a voracious, nasty eagle and then proceed to knock down his glass of water; Eddie Warburg had polish, and a deep, broad smile. His connections helped too. The world of philanthropy and patronage is full of tit for tat, and it was hard to turn down one of the banking Warburgs if he asked you to be a trustee or, later on, to lend artworks. Moreover, Eddie or his father could always cover any deficit the new society might incur. And John Walker could help in his special way. Particularly attuned to the Social Register set, looking every bit the well-bred American aristocrat, Walker had the sort of friendships that enabled him to build up the list of sustaining members. Kirstein and Warburg were not really his typical companions; he specialized more in “a number of rich, hard-drinking, bridge-playing friends”11—exactly the sort of people one needed to provide funds for a fledgling arts organization.12 On his own, none of these three young men had what it would take to get a conservative community to consider and support radical art, but as a team they could pull it off.

Lincoln Kirstein had started early as an artistic adventurer. Born in 1906, he was eight when he created “Tea for Three,” a dramatics club in which he, his brother George, and their neighbor William Koshland were the members. Even then, he was a systematic organizer. There would be two performances at the Kirsteins’ house on Commonwealth Avenue, followed by one at the Koshlands’ on nearby Beacon Street; then the pattern would be repeated. For costumes, the boys pulled things out of their parents’ closets. Lincoln produced, wrote, and starred in all their plays. They were his obsession; when he and Koshland played baseball at school, and were invariably in the outfield, Lincoln was generally too busy planning the next production to notice when the ball came.

Even before Lincoln Kirstein entered Harvard at the age of twenty, he knew his way around the worlds of art, dance, and literature. When he was fifteen, he published a play—set in Tibet—in the Phillips Exeter Monthly. In 1922, when he was sixteen, he made his first art acquisition—an Ashanti moon-fan figure of tulipwood, carved at the Wembley Empire Exhibition. That same year, he and George spent their summer holidays in London in the house their older sister Mina shared with Henrietta Bingham, of the Louisville publishing family. The boys were asleep after a performance of Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes when they were roused from their beds and told to put on Mina’s orange-and-yellow silk pajamas to dance a pas de trois improvised for them by the brilliant soubrette Lydia Lopokova. Lytton Strachey was among those who viewed the Kirstein brothers’ carrying-on. Lopokova was there with her fiancé, Maynard Keynes. A few days later, Keynes took Lincoln to a Gauguin exhibition that Lincoln found unforgettable. He relished these new ways to look at life, and the pioneering styles in which to write, dance, or paint.

Like the setting Lincoln had helped to create for the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, Mina’s London life was a far cry from the environment in which they had grown up. Their father, Louis Kirstein, was a high-ranking executive—eventually chairman—of Filene’s Department Store. The Kirsteins’ house was very much the sort of thing Lewis Mumford excoriated in Harper’s. The foyer was hung in green corded silk. Empire Period torchères, and a marble bust of Louis XIV’s finance and culture minister, Colbert, sat on its green marble mantels. The rooms upstairs emulated Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Italianate palazzo, Fenway Court. There was a Chinese bedroom completely done with scarlet slipper-satin and black lacquered furniture, niches stuffed with neo-Classical art, and a library decorated with electrotypes of Pompeiian bronzes. A tailor’s daughter, Rose Stein Kirstein liked to have as much lace around as possible. The largest painting was a full-size copy of Titian’s Bacchus & Ariadne. Everything referred to some other place and some time past. This was equally true in the Boston Public Library, of which Louis Kirstein was president. Lincoln regularly visited his father there, crossing inlaid floors under the grand barrel vault with its ornate ceiling reliefs and abundance of marble columns. What Lincoln Kirstein was used to were embellished surfaces and grandiose manifestations of the stages of history.

From left to right: Lincoln, Louis, and George Kirstein in 1910. (Photo Credit 1.3)

Lincoln Kirstein, photographed by Walker Evans, c. 1927. (Photo Credit 1.4)

Cover of The Hound & Horn, Spring 1928.

Lincoln’s own tastes went in many directions. When he was twelve his mother had taken him and Mina to Chartres. There he developed such a strong passion for the windows that between high school and college he worked for a year in a stained-glass factory. This fulfilled his father’s wish that he learn what an honest day’s work meant, and also brought him closer to the craftsmanship that was his heritage, since his paternal grandfather had been a lens grinder in the German city of Jena. Early on his mother had given him two large volumes of masterpieces of world art, and he had been overwhelmed by a Dürer. On summer vacations he looked long and hard at paintings in northern European museums, and made drawings of classical sculpture in the Louvre. At home in Boston he studied decorated books and bought volumes illustrated by Gustave Doré, Aubrey Beardsley, and Arthur Rackham, of whose work the best collection was in the public library. Lincoln also greatly admired the large allegorical murals there: Puvis de Chavannes’s The Muses of Inspiration, Edwin Austin Abbey’s The Quest and Achievement of the Holy Grail, and John Singer Sargent’s Judaism and Christianity. He often met his father in the boardroom, where Sargent’s panel of the prophets looked down on them; it moved him greatly.

Alfred H. Barr, Jr., photographed by Jay Leyda, New York, 1931–33. Gelatin silver print, 4¾ × 3⅝″. (Photo Credit 1.6)

In his first year of college, Lincoln Kirstein went with his mother to the auction of the American collector John Quinn and bought an eight-inch-high statue of a mother and son made in the Belgian Congo. The piece had been found by Paul Guillaume—the Paris-based dealer in African art—and it was Picasso who had advised Guillaume to offer it to Quinn. There was little that Kirstein wouldn’t consider so long as it reflected passion and competence. At Harvard he did quite a bit of painting himself, most of it in a rather traditional figurative style. He had heard the painter Leon Kroll say that if a painter had not done a thousand life drawings by the age of twenty, he should forget it. Kirstein did more, in the traditional style one might expect from an artist whose artistic heroes included Antonello da Messina, Antonio Moro, and Anthony Van Dyck. Above all he painted portraits, which by his own description were in the manner of artists ranging from Holbein to Cézanne.

The one rule was that whatever Kirstein cared about, he cared about vehemently. His freshman year at Harvard he and some associates started an undergraduate magazine called The Hound & Horn, the first issue of which came out in the fall of 1927. Deeming Harvard’s official literary magazine inadequate, this new publication was modeled on the Criterion, an English review edited by T. S. Eliot. Like everything Kirstein was to be involved in from that point on, it did not flaunt his name—which appeared only in small type in the list of editors—but the periodical was his idea, and bore the mark of his very strong sense of judgment.

Kirstein selected authors for The Hound & Horn who at that time were little known. They were mostly young and unproven. In general their styles were streamlined, their messages candid to a fault. They were bound by no remnants of Victorianism or other old-fashioned forms of acceptability. Independence marked whatever arenas the magazine entered: literature, architecture, painting, photography, music. The first issue had an article called “The Decline of Architecture” by the young architectural historian Henry Russell Hitchcock, along with photographs of recent building design by a young man named Jere Abbott. Abbott was a graduate student at Harvard under Paul Sachs, as was the person with whom he shared an apartment on Brattle Street, Alfred Hamilton Barr, Jr. Both Barr and Abbott were Kirstein’s advisers.

Abbott’s photos showed the New England Confection Company factory in Cambridge. That Necco building today looks like a straightforward industrial structure, but its inclusion as a triumph of design was startling in 1927. To extol the beauty of unornamented, machined, and coolly functional form was a major step, and a challenge to the usual way of doing things. In advocating this radical aesthetic through The Hound & Horn, Kirstein was reflecting Alfred Barr’s taste. Besides studying at Harvard, Barr was teaching a course in modern art at Wellesley College. In it, he applauded the Necco factory and assigned his students to visit it. Barr had also written the wall labels for a show of facsimiles of modern paintings at the Fogg. The artists he championed included Gauguin, Matisse, and Picasso. By the standards of the times they were not quite as offbeat and shocking as many of the artists the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art would show, but they evinced Barr’s commitment to some fairly adventurous art.

The Hound & Horn issues of the next several years included short stories by Conrad Aiken, Katherine Anne Porter, Kay Boyle, Erskine Caldwell, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein, all of whom were new writers at the time. There were excerpts from a novel by John Dos Passos. A story called “Bock Beer and Bermuda Onions” was by the twenty-year-old Jon [sic] Cheever. There were essays by Paul Valéry, Sergei Eisenstein, and T. S. Eliot, as well as an Eliot bibliography prepared by the Harvard student Varian Fry and an essay about Eliot by R. P. Blackmur, who contributed frequently. The poetry was by Malcolm Cowley, William Carlos Williams, Conrad Aiken, e. e. cummings, Horace Gregory, Wallace Stevens, and Ezra Pound. There was also one poem by Captain Paul Horgan, identified as a teacher of English at a military school in the Southwest. Roger Sessions contributed “Notes on Music,” and Hyatt Mayor wrote a piece on Picasso’s method. There were occasional reproductions of paintings—mostly easygoing watercolors—by A. Everett Austin, the very young Fairfield Porter, and Charles Burchfield. Richly printed black-and-white photographs were by Charles Sheeler and Walker Evans. The latter was represented by, among other images, his striking portrait of a fur-clad black woman on Sixth Avenue in New York, and Wash Day, a shot of laundry hanging on lines.

The back of each issue contained book reviews. When they were both freshmen, Kirstein had asked John Walker to write some of these reviews. Kirstein had initially set out to meet Walker after hearing that his room was covered with reproductions of paintings by Duncan Grant, John Marin, Picasso, and Vlaminck. This must have made it seem like home territory to Kirstein, since in 1924 Duncan Grant had done a portrait of Mina; it was also like a sign on the door saying “interested in modern art and other unusual things.” Sensing that here he would find a soul mate, one day Kirstein had walked in and introduced himself. Their rapport on The Hound & Horn had led Kirstein to ask Walker to join him in the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art.

John Walker’s fondness for art had been the result of a calamity. In 1919, when he was thirteen years old and interested only in football and skiing, he had been struck with infantile paralysis. His family lived in Pittsburgh, but his mother took him to New York so that he could get the best medical treatment. For two years they lived at the Biltmore Hotel. She would regularly wheel John, who was dressed in his pajamas, up and down Fifth Avenue in an open barouche. When his health improved to the extent that he could get into clothes, she sought places accessible by wheelchair, and the easiest was the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with its street-level side entrance, and elevator. At the Met Mrs. Walker saw her son smile with a pleasure she hadn’t seen on his face since before he had taken sick. He spent endless hours in the ancient and classical collections, and then discovered the galleries of Dutch and Flemish art of the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries, where he liked to park his wheelchair for prolonged viewings. In little time he knew that he wanted to be a curator.

John Walker III and his parents in Palm Beach, c. 1912.

John Walker III, Harvard College Class Album photograph, 1930. (Photo Credit 1.8)

When Walker and his mother moved back to Pittsburgh, he began to attend the International Exhibitions at the Carnegie Institute. These annual shows were among the few venues in America for modern European art. Walker loathed the pictures his family owned—canvases by chic minor painters like Fritz Thaolow and Aston Knight—but admired much on the contemporary scene. At his country day school he helped form a group of half a dozen boys in which the members took turns reading one another papers on the history of art. When it came time for college Walker chose Harvard because he knew that this was to be his field and people like Sachs and Forbes were there. The family fought hard—everyone else had gone to Princeton or Yale—but he knew what he wanted.

On a visit home during his freshman year, Walker made his first art acquisition—a painting by John Kane called Old Clinton Furnace. The asking price at the Carnegie International was fifteen hundred dollars; he offered seventy-five. The saleswoman at the catalog desk laughed in his face, but the next day she telephoned him, chagrined, and said his offer had been accepted. Walker knew Kane slightly; the artist’s wife had been his grandmother’s cook. He also was well acquainted with the subject of the canvas; it was the blast furnace in central Pittsburgh that his grandfather owned. But to buy a rather primitive rendering of smokestacks and an industrial landscape was a bold move. Walker, however, had long valued what others deemed grim. As much as he enjoyed the galleries at the Met, he had also come to prize the sights of downtown Pittsburgh. As a teenager he spent hours watching work at that blast furnace. He found a bizarre beauty in the flying sparks and workmen sweating away in the hot light. When on one occasion the furnace collapsed and molten iron flowed down a main street of Pittsburgh, he could not take his eyes off this glorious “avenue of glowing pig iron.”13 When Lincoln Kirstein entered Walker’s room to tap him for contemporary, experimental ventures that required an original outlook, he had picked the right person.

Not that Walker had had any more exposure to contemporary style at home than Kirstein had. The rooms in which he had spent most of his time as a child—in his maternal grandparents’ house in Pittsburgh—resembled an elegant English men’s club. They were paneled in mahogany, oak, and walnut. There was chintz everywhere, windows draped in dark brown or dark red velvet, elaborately stuccoed ceilings, massive silver lamps, and leaded glass doors in front of bookcases crammed with leatherbound volumes that had been bought by the yard. Walker’s paternal grandparents’ house was decorated with William Morris wallpaper and furniture, and Tiffany lamps and chandeliers. Like Kirstein, Walker had grown up in an atmosphere redolent of the widespread American reverence for established traditions. What made a style legitimate was that it had already flourished in Europe for centuries.

Lincoln Kirstein’s and Eddie Warburg’s families had tried to get the two young men together long before they actually met. Louis Kirstein was a friend of Eddie’s brother-in-law, Walter Rothschild. Rothschild was married to the oldest of the five Warburg children—the only girl, Carola. He was sixteen years older than Eddie and one of the top people at Abraham & Straus. A prominent figure in Jewish philanthropy in Boston, Louis Kirstein also admired Eddie’s father, who headed many New York charities in keeping with the tradition established by Eddie’s maternal grandfather, the wealthy financier Jacob Schiff. From Louis Kirstein’s and Walter Rothschild’s points of view it made perfect sense for the two students to be friends, because of what they shared both in their backgrounds and in their unusual interest in art. But like most family efforts to create friendships, their initial attempts had backfired. Lincoln and Eddie had carefully avoided each other for almost all of freshman year. By the end of the year, however, the two students discovered that in spite of their families’ intentions, and Warburg’s being two years younger, they had a lot in common. Well before the time that Kirstein was concocting the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, they had become fast friends. Warburg had a lot of money and was inclined to be generous with it, which contributed significantly to Kirstein’s feeling that he could make the new organization a reality.

Felix Warburg had advised his son to choose distinguished friends who would give sound advice. He warned Eddie against “the money-mad crowd” and mere country clubbers. In spite of his own fondness for “cheerful hours of sport,” one had to avoid friends who were good at nothing else. He counseled his son to find “one right companion” instead.14 For Eddie, Lincoln Kirstein was just the sort of intelligent and inspiring companion his father had in mind, even if he wasn’t “right” in the sense that Eddie’s older brothers would have considered “right.” Although Kirstein had spent a year at Phillips Exeter and two at Berkshire Academy, he had previously gone to public schools and wasn’t part of the prep school set. He was the opposite of the easygoing jocks and party boys whom the other three Warburg boys counted as friends. Kirstein cared about books, paintings, and the dance, not about sports and socializing. He could be abrasive in defense of his passions. He was as vituperative as he was imaginative. But he had a sensitivity and awareness that gave Eddie rare ease, and a boundless knowledge and energy that nourished Eddie more deeply than anything on the Harvard curriculum could. Moreover, by recognizing the infectious power of Eddie’s wit and kindness, Kirstein enabled the baby of the Warburg household to be effective and useful. To help Kirstein implement his ideas gave Eddie a sense of his own worth.

The art that Eddie Warburg knew best before college was what he could find by walking downstairs in his parents’ house. This was a neo-Gothic François Premier-style mansion overlooking the Central Park Reservoir at Fifth Avenue and Ninety-second Street (today it is the Jewish Museum). Designed by C. P. H. Gilbert, the house had painted beam ceilings, elaborately paneled walls covered with tapestries or other collections, ornate wrought-iron lamps and chandeliers lighting the heavy English furniture and the ceremonial silver with which Jacob Schiff had filled his daughter’s household to assure proper Sabbath celebrations. Everywhere there were layers over layers, which is what life itself was like. The entrance vestibule had double doors made of glass panels framed with ornate bronze mullions and covered with Belgian lace.

Eddie’s father devoted two rooms to a comprehensive collection of early German and Italian woodcuts and Rembrandt etchings that he had built up under the tutelage of William Ivins, a close family friend and a protégé of Paul Sachs; Sachs had recommended Ivins to his position as the curator of prints at the Metropolitan Museum. In the red room Frieda and Felix Warburg kept the paintings they would bring back as souvenirs of trips to Rome, among them four predellas (base panels), attributed to Pesellino, that had originally belonged in a large altarpiece completed by Fra Filippo Lippi after Pesellino’s death. In the conservatory adjacent to the red room there was a so-called Botticelli, in front of which stood on a stand a so-called Wittenberg Bible with a so-called inscription by Martin Luther. In time it would fall upon young Edward to find out the truth about the authenticity of these works. When he was a teenager it was often his task to give visitors the tour of all of these objects when his father had to take a phone call from “downtown”—the offices of the investment banking firm Kuhn, Loeb, where he was a partner—or was off raising money for one of the many charities he supported. Of the five children, Eddie had always been the one to show an interest in art; while his brothers were on the fifth-floor balcony leaning over the elaborate oak balustrade having a spitting contest into the marble amphora in the hall below, he was listening to his father and visiting art historians or other curious onlookers in the two print rooms. As they went through the collection covering the walls, encased in double glass on rotating pedestals (this to allow the viewing of both recto and verso of two-sided images), or stored in black boxes on a billiard table, he carefully noted every scholarly observation as well as all the more prosaic remarks he would store away into his repertoire as a mimic. His parents encouraged his interest in art through a practice then known as “bratting”—akin to tutoring, but less formal—in which an older boy is hired to encourage another in a given field. Eddie’s coach was Jo Mielziner, the painter and set designer, who gave him instruction during summer holidays in Aunt Eda Loeb’s Seal Harbor home. Eddie also was tutored in music—by Arthur Schwartz, the composer who later wrote “Dancing in the Dark” and other Broadway hits. Schwartz regularly took his young protégé on strolls through Central Park, where he would teach him new tunes.

Edward M. M. Warburg, c. 1927. (Photo Credit 1.9)

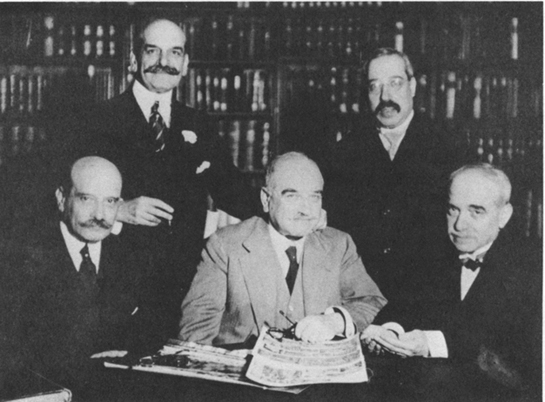

The Warburg brothers in Hamburg, c. 1925. From the left: Paul, Felix, Max, Fritz, and Aby, whose hands are held in a gesture of supplication to signify the financial arrangement with his brothers.

Felix Warburg’s brother Aby had established a precedent in the family for devoting one’s life to art. The oldest of the five brothers of whom Felix was the youngest, he was, according to family tradition, entitled to be a senior partner in the Hamburg banking firm M. M. Warburg & Company; like some sort of royal status, such positions were reserved for the oldest two sons. Aby agreed, however, to abdicate—on the condition that his younger siblings would guarantee lifelong support of his research in the field of iconography. Ensconced in his book-filled house in Hamburg, he pursued the consistent use of certain motifs and images in diverse cultures. He opened his library to people like the psychoanalyst Ernst Kris; Erwin Panofsky, whose writings on iconography pioneered the interpretation of symbolism; and E. H. Gombrich, who in time would write The Story of Art. (Years later, after Nazism forced the removal of Aby Warburg’s library from Hamburg to London in a dramatic nighttime exodus by boat, Gombrich would head the Warburg Institute at the University of London and write Aby Warburg, An Intellectual Biography.)

The Warburg house at 1109 Fifth Avenue, c. 1920. (Photo Credit 1.11)

But what appealed to young Edward more than the scholarship of his uncle or the collecting of his parents was the idea of public service. Art was not just something to be studied in libraries or enjoyed in the privacy of one’s home. Consider what happened to the Pesellino predellas. Just at the point when Eddie was getting to know them well, they were packed up and sent off on loan to the National Gallery in London. For many years the altarpiece of which they had originally been part—The Trinity with Saints—had been disassembled. The National Gallery had purchased one part of it in 1863, and received another by bequest and purchased a third in 1917. Then, in 1929, a fourth panel, formerly in the Royal Collection, had been presented thanks to Lord Duveen. All that was needed to complete the work was for Felix Warburg to lend the four predellas. A couple of months after sending them, Felix stopped by to see them in London. To his shock he found that not only had the altarpiece been reconstructed, but his panels had been fitted into its base as if they had always been there. Moreover, the predellas were now attributed to the studio of Fra Filippo Lippi. Naturally Felix was pressed both to accept the change of authorship and to turn the loan into a gift. He agreed only after negotiating the terms, which consisted of an agreement that Parliament change existing laws in order to permit loans of British-owned paintings outside England, a deregulation from which the larger world still reaps the benefits.

This concern for public need was typical of Felix Warburg. In 1914 he had become the first treasurer of Jacob Schiff’s creation known as the JDC—the Joint Distribution Committee of American Funds for the Relief of Jewish War Sufferers—which he then chaired for eighteen years. He also headed the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, organized the Federation of Jewish Charities and became its first president, and was a leading figure in the American Jewish Committee, the Refugee Economic Corporation, the American Arbitration Association, the Philharmonic-Symphony Society, and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, many of which he had helped to start. Felix used to liken himself to Heinz’s pickles; in his office at Kuhn, Loeb he had had a special screen built with fifty-seven panels in it, each of which opened to a file case with material concerning one of the boards or committees on which he served. By supporting the sort of art too advanced for museums, Eddie had stepped far from the family orbit, but the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art was also a new and original form of public service, and as such it was very much in the family tradition.

Paul Sachs had started out in the German-Jewish banking circle in New York; he had for a number of years been a partner in his family’s firm, Goldman, Sachs. But as an investment banker, whenever he earned commission money he immediately used it to buy art, which was his true passion. A graduate of Harvard College, Sachs had been asked onto the Visiting Committee of the Fogg in 1911; it was four years later that he realized that art had to be his profession rather than his hobby, moved to Cambridge, and changed careers. But he still had his hand in the closely allied society from which he came. He persuaded Felix Warburg and other old New York friends to take an active role in the Fogg by joining various committees, and to support the museum with generous gifts. By studying with Sachs, Eddie Warburg was playing a part in his father’s grand life scheme. Felix Warburg had helped Sachs immeasurably in building up the Fogg. To advise Edward was Sachs’s way of repaying the kindness and Felix’s way of directly reaping the benefits of his largesse.

For Eddie Warburg, however, Sachs was “a humorless little cannonball of energy” who flaunted his Phi Beta Kappa key and cried a lot.15 His rages were frequent, especially toward those who weren’t lucky enough to be his social inferior. Sachs was a reverse snob, and found it hard to accept others of his background as serious academics. To be a truly diligent art historian who could recognize authorship and pinpoint iconography, you had to know what it was to work hard to get to where you were. Except for himself, there were to be no gentlemen scholars. It was all right for Sachs to have gone from being an investment banker in the family firm to being an art collector, and from there to being professor and codirector at the Fogg while living in one of the finest houses in the region, but this sort of easy route would not do for anyone else. For that reason Sachs generally treated Kirstein, Warburg, and Walker with the disdain that the rich reserve only for their fellow rich. He resented the three young connoisseurs the way that people who fancy themselves an elite, with exclusive claim to their cultural discoveries and position, resent those who threaten their monopoly on taste and their privileged status as pioneers.

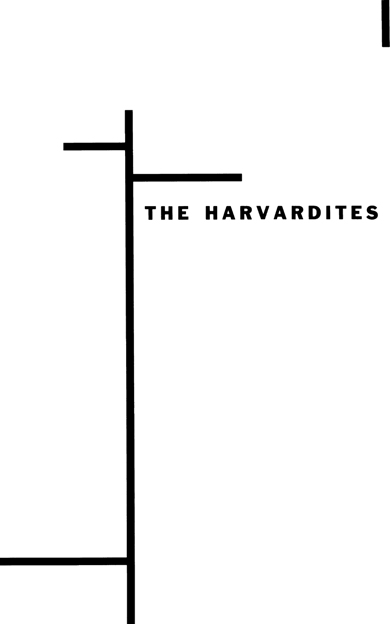

Faculty of Harvard University Fine Arts Department, Fogg Art Museum courtyard, 1927. Seated in front are Paul Sachs (far left) and Edward Forbes (second from right). (Photo Credit 1.12)

Lincoln Kirstein considers Sachs to have been “a small and nervous man, who hated being a Jew”16—and who mainly was very impressed with himself because he lived in Charles Eliot Norton’s homestead. From Kirstein’s point of view, the extent of Sachs’s support of the Harvard Society was that he indulged it; “it was nice if little boys played.” He was willing to go that far because the society got him off the hook about the most modern art, a subject with which he was basically uncomfortable. But he was afraid that the new project would get out of hand, and his support was always tentative. As far as John Walker was concerned, Sachs was above all “a stocky, strutting little man” who never could remember who Walker was—“a disheartening experience for a student who had come to Harvard especially to sit at his feet.”17

The general take on Sachs, however, is that he was a talented navigator in the ways of the world. His “museum course” was the training ground for many of America’s future museum directors. Sachs placed scores of people in their jobs; he knew which museum trustee to call in which city. He also kept track of collectors everywhere, thus enabling students to study their holdings, and to secure loans later on when they were working at museums. But much as Kirstein, Warburg, and Walker benefited from Sachs’s letters of introduction to get into the collections in Boston, New York, and Washington where they might see some of the latest art, they often found negotiations with their professor to be torturous.

Edward Waldo Forbes, on the other hand, backed the Harvard Society completely, whatever the limitations of his understanding of contemporary art. A grandson of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Forbes was an easygoing Bostonian gentleman of the old school. He had his misgivings about modern art at the Fogg, but he sanctioned it at the Coop. Even Forbes, however, could not keep peace between the Harvard Society’s founders and Paul Sachs. To deal with Sachs—which was essential if their organization was to take off—the students needed a devoted intermediary. Time and again they brought on Sachs’s ire. Warburg’s problem was that he was outspoken and funny at any cost; Kirstein’s that one moment he might be friendly and gracious, in another he could turn painfully awkward or nasty. Walker was too smooth and upper-class confident. But in Sachs’s assistant, Agnes Mongan, they had the perfect diplomat to run interference between them and the man to whom they ultimately had to answer for their new vehicle for modern art. They also had a fellow believer. Even more than the three young men, Mongan had come to view artworks as emblems of human life lived deeply and as gateways to peerless emotional adventure.

At a younger age than any of the founders of the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, Mongan had recognized her own passion for paintings and objects. Born in 1905, she was twelve years old when her father asked her what she wanted to do when she grew up. Dr. Mongan—trained as an obstetrician/gynecologist, but now a family doctor with a general practice—had just come in from his hospital rounds when he posed the question. He and Agnes were alone at breakfast in the family house in Somerville, a town that neighbors Cambridge. The young girl did not know the term “curator” or “art historian,” but she pointed to a Persian rug—of which her parents had bought a number at auctions—and replied, “I’d like to know something about that.” There was an eighteenth-century reflector on the wall. It had a convex mirror topped by an eagle, and she adored it. Directing her finger from the rug to the reflector, she then said, “I’d like to know something about that, too.”

“And that,” she added, indicating some silver on the mantelpiece.18 Her father replied that in that case she should have the best possible liberal arts education a girl could have, which meant Bryn Mawr. Having settled the matter, Dr. Mongan started to leave the room, but he stopped at the door and came back. He told his daughter that her time at Bryn Mawr should be followed by a year in Europe. Dr. Mongan believed that one had to have a taste of the larger world; not only did he never let a day go by without picking up his New York Times at a Cambridge newsstand, but he also received the Manchester Guardian and Le Monde by post. Having himself spent a year abroad after Harvard Medical School, he felt that each of his children should have the same opportunity. Unlike Kirstein’s and Warburg’s parents, he would not leave his children a fortune. They would need to support themselves. But what he could provide were optimal opportunities for learning.

From the start, the senior Mongans had stressed the acquisition of knowledge for their children. Before her marriage, Agnes’s mother, like her many siblings, had been a schoolteacher. She read the classics to her two sons and two daughters for an hour each night, and saw to it that Agnes and her sister Elizabeth learned to play the piano. During successive summer holidays in Maine, the children were taught one year to identify all the local species of wildflowers; the next, mushrooms; and the following, trees. When Agnes’s father settled on the idea of her going to Bryn Mawr, he and her mother studied the college catalog. They decided to switch her from Somerville High School to the Cambridge School for Girls so that she could learn Latin, French, and a bit of Italian, and strengthen her background in mythology and literature. It was the sort of discipline from which art historians are made.

As a young girl, Mongan had won a prize for a piece in the St. Nicholas Magazine. She liked to write as well as to learn about artworks. At Bryn Mawr she majored jointly in English and history of art. Mongan’s main interest was clearly in the latter, however; what her study of English provided above all was a better command of language with which to describe the art objects that held her captive.

At Bryn Mawr there were only three teachers of art history: George Rowley for Oriental art, Edward Stauffer King for northern Renaissance art, and Georgiana Goddard King (no relation to Edward) for everything else. Professor Georgiana King, who had started as a teacher of English, had created the art history department at the college and turned it into one of the best in the country. She had opened the field to women by making Bryn Mawr the first women’s college in America to offer a Ph.D. in the subject. On her clearly defined course of becoming a professional art historian, Agnes Mongan could have chosen no better mentor. King was not only immensely knowledgeable, but she was passionate and colorful; everything about her suggested that to follow her way of life would be fulfilling and amusing.

The Mongan family, c. 1915: Agnes and her brother Charles in the background, their parents in the middle, her brother John and sister Betty in the foreground. (Photo Credit 1.13)

Agnes Mongan sitting on running board of Nancy Williams’s car, c. 1928.

As the head of a department in which men held subordinate positions, King demonstrated that here was a line of work in which a woman might attain the highest stature. In 1914 Bernard Berenson, the renowned connoisseur and scholar, had called King “the best equipped student of Italian art in the United States or in England.”19 Berenson, who had moved to Italy but remained deeply immersed in American collecting and the academic scene, had praised King to the president of Bryn Mawr by saying that only two years after she had founded the art history department there she had created the finest photograph and slide collection anywhere. “B.B.” went so far as to ask “G.G.”—this is how both were known—to work for him. But, with an institutional loyalty that also became a model for Mongan, G.G. was too attached to the college to leave it. She had attended Bryn Mawr as a student. By the mid-1920s, when Mongan studied with her, she had been there for twenty years, and she would remain for another ten. The venerable institution offered a secure base for a life of adventure and wandering. G.G. went to Europe regularly, often exploring unknown and inaccessible regions of Spain in her search for medieval and earlier artworks. She periodically traveled with Gertrude and Leo Stein, who admired her as a literary critic and a poet; she had struck up a close friendship with Gertrude in 1902 and on visits to Paris became acquainted with many of the artists and writers in Gertrude’s life. G.G. was a scholar of Oriental philosophy and of ancient Greek, Latin, and Arabic—in addition to the subjects and languages more directly related to art history. But she always returned to her teaching, enjoying it on her own terms as a campus eccentric. For thirty years G.G. wore the same frayed academic gown as she moved about the Bryn Mawr campus. At dinner she dressed as a Spanish doña, generally in a fitted black suit, often with black lace on her head. The short, stocky woman, with her lively green eyes and her gray hair in its bun, was known for her intolerance of mediocrity and dull people. She was often deliberately contentious. She was so fanatical about grammar and correctness that in her early teaching years she had written The Bryn Mawr Spelling Book, more than one hundred pages of words frequently misspelled. In Agnes Mongan, who was one of her best students, she met her match for enthusiasm as well as for accuracy of language. G.G. had also found her equal in tenacity; Mongan was frail and prone to severe bouts of grippe, so much so that at one point King declared her not strong enough to continue in fine arts and sent her home, only to have Mongan promptly return with an opinion from her father that they had underestimated her.

Georgiana Goddard King. (Photo Credit 1.15)

For Mongan, King was a model not only for factual rectitude, but for a belief in art as a spiritual presence. G.G.’s teaching emphasized original observation more than the accumulation of information. In her courses on medieval art, Italian Renaissance painting, and modern art—about which she learned firsthand from the Steins—she lectured spontaneously, rarely glancing at notes. She deliberately eschewed syllabuses or course outlines. The lecture room was totally dark except for the lights of the slide projector, so that students could scarcely take notes. Rather, the young women were to immerse themselves in the visual organization of the paintings and the emotions at play.

Agnes Mongan reveled in what she called “King’s capacity to arouse, to electrify, to instruct, and to inspire.” On many levels, her teacher became her ideal. She admired King’s power to leave her students “inoculated with ideas which leave marks on all their later lives.” Here was “a scholar of profound and original research” who went well beyond the realm of scholarship. For Mongan it was impressive that King pursued knowledge and information tenaciously, but what mattered more was that to her other attributes “were added a poet’s sensitivity and an unfailing human sympathy. Against this background the work of art was contemplated and judged. Never was it considered as an isolated object remote from life.”20

Intense aliveness was what Agnes Mongan craved; artworks and their study were vehicles toward it. Not only did Georgiana King recognize the power of paintings and sculpture, but in researching, writing, and teaching about art, she lived richly. King was alert to everything. She charged every moment, not just for herself, but for those who came into her wake. G.G. had the power to heighten experience, and to unveil new extremes of vitality—for which Mongan had enormous appetite. When Mongan characterized the experience of King’s students, she described not only her own spiritual adventure, but also her own aspirations for the effect she too would like to have on others:

They know … that adventure lurks at every cross-road.… For them saints have awakened from stone to living spirit, and sightless eyes have looked beyond the boundaries of this world. The symbol has been made significant. Legend and liturgy have uncovered their riches. They have been moved by the beauty of pure line and stirred by the majesty of form.… From the Far East to Santiago, from the wall paintings of Altamira to Picasso, they know that “it is always the spirit which moves man to the creation of lasting beauty.”21

At Bryn Mawr, Mongan came to feel the intoxication with visual riches that would determine her life’s work. She would never lose her regard for precise knowledge and accurate identification she had acquired on those summer nature walks in New England, but the word “magic” also entered her vocabulary and assumed an importance it never would have for more traditionally Germanic, iconography-minded art historians. For one of King’s courses Mongan wrote a paper on El Greco in which, in her neat schoolgirl script on lined paper, she evinced the intense emotional engagement, both visual and psychological, that would inspire more than sixty years of work. At the same time she reached—if not with quite the success that she would later attain—for the writing style that would seal her success. She also manifested her originality:

Anyone who has seen an El Greco canvas is not likely to forget it. His colors are weird—chalky and often livid. His canvases are packed, even the landscapes are so thickly packed that one could not move through their heavy air. But more striking than any of these is the look in the eyes of his people. They seem, without any of the feline and sinister quality of Mona Lisa, to look beyond this world to another.

At that point in her life, Mongan had traveled no farther than the eastern seaboard of the United States, but this did not prevent her from grappling nobly with the milieu in which these paintings had been made. She imbued El Greco’s Spain with profound drama, about which she wrote with an ardent voice that seems intended for far more than the one-person audience who would be reading this paper:

All who really know Spain know her to be a land of violent and constant contrasts—and in these contrasts lies her fascination. On her plains the dry and scorching heat, which beats down with merciless intensity, suddenly gives way to icy winter winds which whistle across the same plains just as mercilessly. In her people profligate voluptuousness is gone in a night and in its place there is an opposite extreme of austere ascetism [sic]. Passionate devotion to the Virgin exists, with no sense of incongruity, side by side with a love of bull fights. Beauty and ugliness are close and good neighbors, beauty lending the ugliness strangeness, and ugliness lending beauty strength—an arid, barren plain and in its midst a city of fairytale splendor, a cathedral gorgeous with the accumulated treasures of centuries and in their midst a skeleton; the Infanta and her dwarf, Sancho Panza and Don Quixote.

In juxtaposing the simultaneous devotion to Catholicism with more earthbound pleasures, Mongan may have been confronting her own personal dilemmas as well as the background for El Greco. But whatever the conflicts, it was her Romantic vision that won out. She wrote of her subject, “He could paint the human figure with all its rounded contours—but chose to paint the human soul.” The conclusion to her paper is, “In El Greco there is positive magic.”22

After graduation from Bryn Mawr in 1927, it was time for the year in Europe. Dr. Mongan hoped it would be in Oxford or Cambridge and that Agnes would become a writer; her choice was Florence, so that she might study Italian art. She joined a master’s degree program organized by Smith College. Led by two professors, Mongan and four other students, all women, spent five months in Florence and the surrounding Tuscan cities. By daylight they viewed art in galleries and churches and private collections. During classes each evening from 5 to 7 and 9 to 11 p.m., they would review everything they had seen. After Florence, the program continued for three months in Paris. On Mondays, when the Louvre was closed, they studied paintings in its galleries through a binocular microscope, from stepladders, and with automobile headlights—while the guards stood around snickering about silly American girls. They went to Berlin, Dresden, Munich, Prague, Vienna, and Venice before returning to Florence, where they had exams in July. Five Italian professors posed the questions in Italian; the women answered in English. There were three hours of oral exams, six hours of written ones. Since a thesis was also required for the Smith M.A., Mongan wrote one on Italian art in the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris. Rich young men like Kirstein, Walker, and Warburg might be able to pursue their love for art on their own terms; a woman of no great affluence had to go the straight and tough academic route. But whatever the struggles, Mongan thrived. Slight to begin with, she lost twenty-five pounds that year, but considered it all part of a nourishing experience.

She had not done enough by the standards of Smith College, however. When Mongan got back to her parents’ house in Somerville and found out that she had passed her exams, she wrote the college to ask that they forward her M. A. Word came back that there were further requirements to fulfill; she needed to take a drawing or painting class. Since she did not want to go to Northampton for this purpose, she signed up at Harvard for Arthur Pope’s course in the theory of design. But her troubles were not over. Three weeks into the course, she got word that she should present herself at the registrar’s office. There she was asked if she was working toward a Ph.D. To her answer that she only wished to complete her M. A., the registrar pointed to the catalog listing where Pope’s course was marked with double daggers. “That means the course has men in it. No woman may take a double-daggered course unless she is working on a Ph.D. President Lowell once discovered a young woman in one of those courses whose serious intent of mind he doubted. He made a rule: No woman may take a double-daggered course unless she is a Ph.D. candidate. Young woman, if you have a quarrel, it is with the president of Harvard University. Good morning.”23

On her way out of the registrar’s office, Mongan ran into the college dean, who came up with a solution. He asked if the same course were offered at Smith, and when she replied that it was, he inquired if the professor there had been trained by Arthur Pope. Again the answer was yes. The dean suggested that Mongan sit in on Pope’s classes, but send her papers to Smith to be graded. By this contrivance, a woman who was not a Ph.D. candidate managed to take a double-daggered course at Harvard and thereby complete her M.A. degree.

That same semester, in the fall of 1928, as a Fogg Museum Special Student, Mongan took Paul Sachs’s museum course. She also took a course that was routine for Harvard art historians—Edward Waldo Forbes’s history of technique, nicknamed “egg and plaster.” Mongan, however, was used to doing more than simply studying three subjects. She approached Edward Forbes about part-time employment, but he replied that part-time rarely worked out. She then suggested volunteer work, which he considered equally fruitless. But three weeks after the semester started, she learned that a friend of hers was giving up her position cataloging the Fogg’s drawing collection under Paul Sachs. She went straight to Shady Hill to ask if she could fill the spot, and Sachs agreed. She ended up as Sachs’s assistant the same semester that the three young men were launching the Harvard Society. Already a great admirer of The Hound & the Horn, Mongan liked the sound of the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art from the moment she heard about it. Not only were the exhibition ideas exciting, but the gentlemen proposing them—especially Eddie Warburg—were irresistible.

Kirstein and Warburg, more than Walker, were responsible for the daily planning of the Harvard Society. Mongan met them almost daily for lunch at the local Schrafft’s as they plotted their course of action and made plans to exhibit the latest painting and sculpture from America and abroad. She was in an ideal position not only to be the Harvard juniors’ confidante and friend, but also their aide-decamp by occasionally presenting or defending their proposals to Sachs, or approaching him on other issues. She had great diplomatic tact. When Frieda Warburg badgered Eddie to find out why, considering all that Felix had done for the Fogg, Harvard had never given him an honorary degree, it was Mongan to whom Eddie could put such an awkward point. She could bring up this sort of issue to Sachs without raising the professor’s hackles. In the case of Felix’s doctorate the answer was no, but Mongan had managed to ask without provoking a storm.

Kirstein and Sachs had violent tempers, while Mongan never gave voice to anger. She knew both how to explain and how to avoid Sachs’s invective. From her employer’s point of view, she was easier than the young men. If Sachs wanted to be the only rich Wall Street type to make inroads in the art world at Harvard, Mongan offered no competition. Sachs treated Mongan far more gently than he did Kirstein or Warburg. A consummate scholar, she provided Sachs a major service by meticulously researching the Fogg’s holdings for his catalog, and he was grateful to her.

From Mongan’s vantage point, not only was Sachs dynamic and knowledgeable, but he had the added appeal that he prized drawings. This was not the norm; although a handful of connoisseurs had always esteemed graphic art, most collectors and museum people cared more for oils. Paintings were easier to display, and made a strong first impression. For Agnes Mongan, Sachs’s elevation of works on paper to the status of high art led to unimagined pleasures. Drawings had a unique freshness. For her they offered the honesty and immediacy that bizarre constructions in wire and cardboard, and other expressions of modernism, provided for Kirstein and Warburg. Art that held a charge of emotion could awaken and enliven these three young people with an intensity they had scarcely felt before.

In many ways, Kirstein, Warburg, and Mongan made a likely threesome. In a milieu where reticence was as much a part of the social code as was a firm handshake, they were violently purposeful. Unlike most of her contemporaries, Mongan wished to spend her time looking at art, traveling, and writing—not planning her trousseau; unlike their peers, Kirstein and Warburg preferred to plan startling art exhibitions than toss a football or worry about how to make more money when they got out of college. But it was not just their ardor that made them among Santayana’s “outsiders … on the fringes of college life.” For one thing, there was the matter of background. Ever since primary school, Agnes Mongan had felt the onus of being Catholic and of Irish descent in Boston. One day a classmate in an early grade had precipitately run her fingers over Mongan’s forehead; when Mongan asked why, the girl explained that her parents had told her Catholics were all devils, and so she was checking for Mongan’s horns.24 It was still the era when employment ads might say “Irish need not apply.” During a vacation from Bryn Mawr when she visited a fashionable classmate in Jamaica Plain, near Boston, she learned that she was the first Catholic and person of Irish descent ever to go up the front stairs of the house; previously they had all used the servants’ staircase. Not that this sort of thing shocked her parents when she reported it back home; Mongan’s mother’s family, the O’Briens, could not be educated in England because they were Catholics, and so had gone to Salamanca.

As Jews, Warburg and Kirstein also felt one step away from the center of things. Even as enlightened a man as Dr. Mongan looked at them askance. Agnes was living back in her parents’ house in Somerville where Eddie called with some frequency. When Eddie told Agnes he was wondering whether her father would ask what his intentions were, she replied, “If you have any intentions at all, he won’t let you in the door.” There were also the clubs that would not consider Jews, the parties at which they would not be welcome.

It was an era when ethnic and religious prejudices were publicly permissible and widespread. For some people there was, in fact, the expectation that Jews should come up with a notion like the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art. Jews were known to be adventurous art patrons. No one disapproved when the art dealer Valentine Dudensing—one of the main people on whom the Harvard Society would depend for loans—was quoted to that effect in a 1927 magazine article. Nor did anyone fault the title of the article: “The Jew and Modernism.” Its claim was that

It is especially to the Jews that we owe the advance in artistic appreciation that has been made in the last decade. The Jews are forward-looking, they are not afraid of doing things unconventionally, differently, individually. Intellectually and artistically they have made great achievements.25

To be viewed a certain way because of one’s religion was an inescapable reality. Having such clear sense of the boundaries of their existence may have contributed to people like Warburg wanting to shatter restrictions in the aesthetic realm.

But being Jewish was not the only determining factor for Kirstein and Warburg. Warburg’s three older brothers, after all, were every bit as Jewish as he was; they simply chose to ignore the fact as best they could. Wishing to assimilate into American upper-class life, Fred, Piggy (as Paul was called), and Gerry easily succeeded. Eddie, on the other hand, had the mixed blessing of being more conscious of everything: his background, his feeling of being the mama’s boy who wasn’t really one of the guys, his relentless sensitivity to his and other people’s feelings. And Lincoln Kirstein had even more of a nonstop mind and inability to screen. In conversation or writing, then as now, he touched on everything and masked little. He has always been blunt about the intensity of both his passions and his dislikes. His religious obsessions range from sharp awareness of his Jewish background, to devotion to the mystic Gurdjieff, to Catholicism. He has been keenly aware of his own difference from most everyone else. This underlies his later depiction of the run-of-the-mill, easygoing undergraduates who were mostly his opposites but who fascinated him:

My school days and college years were gilded by a steady succession of enthusiasms for boys and men whose sweaty brilliance and appetite for hard liquor during Prohibition seemed to liberate them into a princely criminal ambiance. Dynastic breeding, well-nourished muscle resulted in a general arrest of psychic development. They were, for the most part, uninterested in ideas, presupposed cash, and resembled expensive sleepwalkers in a luxurious dream. No hindrance or tragedy touched them, and I was excited by their assurance of command over their immediate situation, even if it led nowhere but to the countinghouses of State and Wall Streets or big city law firms.26

Kirstein may have been enchanted, but it was not his lot in life to follow their course. He and his closer comrades would never entirely fit in with the larger group. They were not good enough athletes. They did not adhere to the same social boundaries. Those who were Jewish were unwilling to try to disguise the fact. To be an outsider was part of their identities.

Kirstein and Warburg were dissimilar in many ways, but both felt apart from the mainstream. One way of coping with their otherness was to cultivate it. If most of their peers regarded them as different, they might as well have a good time and be as outrageous as they wanted. Kirstein and Warburg embraced modernism in part because, knowing that they were out of the mainstream anyway, they elected to foster rather than mitigate their sense of being different.

The Harvard Society’s exhibition of work by living American artists ran from February 19 to March 15, 1929. Although these people’s art has since been assembled in countless exhibitions and books, the joint showing in the two rooms above the Coop was one of the first times it was conceived as part of a general movement. A two-page flyer for the show set the tone and announced its purpose. The abundance of clean white space was as striking as the text. A few succinct, no-nonsense paragraphs in bold sans-serif type contained Kirstein’s description of the exhibition as “an assertion of the importance of American art. It represents the work of men no longer young who have helped to create a national tradition in emergence, stemming from Europe but nationally independent.” The artists for the most part fell into two groups. One consisted of “lyrists” who maintained the “tradition of visual poetry” of Albert Pinkham Ryder. These included Thomas Hart Benton, Arthur B. Davies, Kenneth Hayes Miller, Rockwell Kent, and Maurice Sterne—painters whose work is full of undulating, exotic curves. Their work shares a rough intensity, a look of caring desperately about something. What it distinctly lacks is the “good taste” of pictures by the able but comparatively limp artists whose work was then proliferating in the Boston galleries and arts organizations. The uncouth bravura of the lyrists offered the Harvard Society founders a welcome relief from the excessive politeness that annoyed them in the more fashionable art of the day. Then there were the “realists” akin to Thomas Eakins: George Bellows, Charles Burchfield, Charles Hopkinson, Boardman Robinson, John Sloan, Eugene Speicher, and Edward Hopper. Their canvases in the Harvard show were above all a candid grappling with the realities of contemporary American life. What these paintings depicted were hardly the everyday sights of people like the Kirsteins, Warburgs, and Walkers. Rather, this was the underside of the current national scene—its low-wage earners like Robinson’s doleful-eyed window washers and Speicher’s Quarryman and Miller’s Reapers, and its everyday sights of ferryboats, dock life, and slums. In his frontal, glamourless depiction of tenement housing, Williamsburg Bridge, Hopper encapsulated some of the objectives of these painters, as well as of the students who put them on view: to gloss over nothing, to reveal what was unique to one culture rather than imitative of another, to dwell on the shadows as much as the sunlight.

The exaltation of natural beauty was equally important, however. There was an airy, euphoric watercolor of Mount Chocorua by John Marin, and a Georgia O’Keeffe of a lily. Kirstein’s paragraphs explained that Marin and O’Keeffe fell into neither of the major groups and hence proved the “uselessness of all categories.” (O’Keeffe’s presence also proved the inaccuracy of Kirstein’s reference to the artists as “men.”) To suggest categories and then debunk that notion was typical of the Harvard Society. Its founders were both ardent and humble. They pointed out that while their selection was a vanguard group with traits in common, these were not the only worthwhile contemporary artists in America.

In addition to oils and watercolors, the opening Harvard Society how also presented sculpture by Gaston Lachaise, Archipenko, and Robert Laurent. From the founders’ point of view, Lachaise’s robust, ladorned, and uniquely bold bronze woman was the most important single object of the whole show. In addition, there were design objects. These included an “ash and cocktail tray” by Donald Deskey (lent by the artist), plates by Henry Varnum Poor, a vase by Robert Locher, and contemporary glass, textiles, and pewter. The Harvard Society was not unique in linking art and craft, but to show an ashtray next to an oil painting in an “art show”—and to give them equal billing in the catalog—was a brave step. From the start, there seemed to be very little that these three founders would not consider, and no end to the efforts they would take. For this opening show they borrowed works from near and far: from Helen Frick and the Carnegie Institute in Walker’s native Pittsburgh; from Duncan Phillips, whose collection Kirstein had gotten to know on visits to Washington; from Samuel Lewisohn, one of Eddie Warburg’s New York relatives; and from local sources like Paul Sachs.

The public was happy with the results of their pains. Twenty-five hundred people visited the rooms above the Coop during those first three weeks. A reviewer in the February 20, 1929, Harvard Crimson thought the new gallery was off to a good start: “The informal opening yesterday of the first exhibit by the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art showed a restraint which should do much to ensure the success of the new project. By avoiding the sort of sensationalism which shrieks like a spoiled child for attention, those in charge have ensured a tolerant attitude from the more conservative of their patrons without jeopardizing the interest of the more advanced.” The Boston papers concurred. They gave extensive space to the show and reproduced some of the paintings—with the largest photos given to the Rockwell Kent.

One of the critics who applauded the American exhibition with the most enthusiasm was Alfred Barr. In the April issue of Arts magazine, Barr treated what Kirstein, Warburg, and Walker were doing as a sort of miracle. After discussing the paucity of recent art in the Boston area—and pointing out that “The Museum of Fine Arts has been no more encouraging to the modern than has her sister museum in New York”—he praised the Harvard students and a number of the individual works on view.

Barr also pointed out that not everyone agreed with such an evaluation. The Boston Evening Transcript’s Albert Franz Cochrane may not have lacerated the entire exhibition, but of the Hopper he wrote, “By what pretense can such buildings have a claim on art, which, theoretically at least, is synonymous with beauty? Why then dignify them by making them the subject of a painted canvas?” What mattered to Barr was that in spite of such controversy “eleven hundred people visited the gallery during its first week.” Here was proof that there was a place in the world for a public exhibition space devoted above all to contemporary art even if it might not be to everyone’s liking and had not yet been put to the test of time.

Cover of the exhibition brochure from “An Exhibition of the School of Paris 1910–1928.” The Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, 1929. (Photo Credit 1.16)

Kirstein was disappointed that the opening exhibition had engendered so little controversy. He had hoped for a scandal, to create a “salon des refusés”—anything but the curse of mainstream acceptance in Boston’s conservative newspapers. To get Alfred Barr’s approval was one thing, but to be praised in bastions of tradition like the Boston Herald and the Boston Globe—where the show was applauded—felt like an insult. The effect of the second exhibition, however, was more satisfying. Called “School of Paris 1910–1928,” it drew in hordes—some thirty-five hundred people visited during its March 20-April 12 stint—but the critics responded as if they were engaged in a contest in which the goal was to be as degrading as possible.

The artworks that invoked such wrath in the Boston newspapers violated prevailing American standards of restraint and decency. They were too sensuous, and indulged in an unacceptable emphasis on personal pleasure. Consider the paintings lent by the avant-garde collector Frank Crowninshield, editor in chief of Vanity Fair. Crowninshield had provided a Braque Still Life, nudes by Moise Kisling and Frans Masereel, de Segonzac’s Spring Landscape, and two pieces of sculpture—Despiau’s Diana and Maillol’s Standing Nude. All of these works openly displayed the sort of earthly delights most of their Cambridge visitors either shunned or did not discuss. The Braque still life was probably even more startling than the various nudes. Its dense profusion of ripe quince and pears bulging with life made the simple act of eating fruit almost erotic. The abundance must have seemed like something out of a dream to those accustomed to college dining halls and Harvard’s eating clubs. Looking at the rich, lyrical arrangement of exotic forms, viewers could momentarily bask in far greater luxuriance and ease than was their usual ken.

The painting suggested the lushness that France represented for many Americans at the time. Here was a palpable slice of the Paris that had lured A. J. Liebling, Henry Miller, Waverley Root, and others. For those used to Puritan leanness or the well-organized fruit bowls of American Primitive painting, this small canvas offered life on top of more life: pears at implausible angles, a floating goblet set in a sea of fabric patterns and furniture scrollwork. Stabilizing the composition was a thick green bottle of ruby red wine. Still full enough to suggest plenty, but with at least a glassful of wine gone, that bottle wasn’t merely an object, but implied present delights. Those who weren’t too intimidated to be put off by the new hazy vocabulary of this painting must have had difficulty looking at it and then returning to the dormitory or libraries. One would have longed for the shabbiest Parisian garret instead.

Even more foreign to the Cambridge viewers was de Chirico’s Twin Steeds, lent by Frederick Clay Bartlett of Chicago. For a population whose idea of horses was of well-groomed creatures kept in neat, English-style wooden barns, here was a plumed white horse in front of the Ionic columns of a Greek portico, with broken temple fragments in the foreground and a rushing sea behind. Both horses’ manes blew in the wind so that they resembled flames. To look at such a painting was to be forced to imagine and interpret, either to accept confusion or to consider the incomprehensible and unexpected. That stretch of the mind, of course, was just what Kirstein, Warburg, and Walker were hoping for.