Chick Austin and the Wadsworth Atheneum pulled themselves together quickly after the ballet debacle. There was the new building to finish, shows to mount, parties to plan. Nineteen thirty-four was going to be a big year for them, and nothing would get in the way.

Others anguished while Austin rallied. On October 26, 1933—just days after the ballet had left Hartford—Philip Johnson wrote Austin to say that while he “was very happy to join a non-profit making venture to further the interests of ballet in this country” and regretted having been able to give no more than five hundred dollars toward the Hartford undertaking, he would have nothing to do with the school as it was being planned in New York.

Concerning the new upset I know nothing at all, only that the School is to be founded in New York, is to be a paying venture and is to attempt to route a ballet to regular theaters throughout the country. This is not at all what I understood on our first conversation or Lincoln’s word from Europe, and I regret very much that I will be unable to contribute financially in any way to the new plan. I wish it, as I wish all ventures in the ballet in this country, success, but don’t feel, under the circumstances, that it is much more worthy of support than others which already exist in this City.

Please believe that I am thoroughly in sympathy with anything which you attempt in Hartford and that I will do anything that is within my power to help you personally and your theatre.1

Eddie Warburg had a lot to explain back at 1109 Fifth Avenue. Why had Peeper put so much money into something that had only lasted a week at its first location? Did he really think it would do any better in New York? Shouldn’t he consider just taking a good solid job, like Freddie and Piggy? Why was he always listening to Kirstein, instead of to nice sensible people?

As for Kirstein, he felt “an anguish of embarrassment having put everyone involved in a false position.… I was whipped and sullen, disappointed and ignorant.… I smoldered.”2 The turmoil took its toll on Balanchine too. Shortly after moving to New York he fell extremely ill. He spent much of the end of November and the beginning of December in Northampton, Massachusetts, being nursed back to health by Mina Curtiss. Kirstein, Warburg, and Balanchine all managed to rally for 637 Madison Avenue, but not without some reassessment and spiritual recharge first.

On December 2 Austin announced the acquisition of Serge Lifar’s collection of original designs for scenery and costumes for Diaghilev’s ballet company. The last of Diaghilev’s great male dancers, Lifar was Diaghilev’s heir. Having heard about Lifar’s holdings, Julien Levy had met the dancer in New York. He bought the collection of ballet art in its entirety, knowing that Austin would want it for Hartford. Using ten thousand dollars from the Sumner Fund—an extravagance in the eyes of his trustees—Austin thus obtained the complete assemblage of sketches, pen-and-inks, watercolors, and gouaches. It included many works by Léon Bakst, including his 1911 portrait of Nijinsky dancing in Michel Fokine’s The Spectre of the Rose; four Braques; twenty-four de Chirico costume and set designs, most of them for the 1929 production of Le Bal that George Balanchine had choreographed in Monte Carlo; Jean Cocteau’s 1931 pencil portrait of Lifar; ten André Derains, mainly designs for the 1926 Paris production of Jack in the Box choreographed by Balanchine to music of Erik Satie orchestrated by Darius Milhaud; five works by Max Ernst; four by Juan Gris; four by Fernand Léger; a Matisse curtain sketch; two Mirós; six splendid Picassos including pencil drawings of dancers and a sepia ink set design for the production of The Three Cornered Hat that Léonide Massine had choreographed in 1919; Rouault’s sets for The Prodigal Son that Balanchine had choreographed in 1929; and nine works by Pavel Tchelitchew There were also numerous pieces by André Bauchant, Alexander Benois, Christian Bérard, Paul Colin, Naum Gabo, Natalia Goncharova, Marie Laurencin, and various lesser known artists. Most were for performances produced by Diaghilev to music by the leading composers of the day.

Austin wanted to stage his own great artistic collaboration. With his new Avery Memorial Building opening on February 6, 1934, he had the chance. In 1927 Virgil Thomson had asked Gertrude Stein to write the libretto for an opera for which he would compose the music. Thomson felt that her sort of language would do well sung.3 Stein took on the task. She based the opera mainly on the lives of her two favorite saints, Saint Teresa of Ávila and Ignatius Loyola. Although its cast eventually consisted of fifteen saints in addition to those in the chorus, and it had a prelude and four acts, she called it Four Saints in Three Acts. Its themes were “religious life—peace between the sexes, community of faith, the production of miracles,”4 set to melodies by Thomson that evoked Christian liturgy. Gertrude Stein’s evaluation of it in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas was “It is a completely interesting opera both as to words and music.”

Thomson, who was living in Paris, regularly performed parts of the new opera. He sang the various roles himself. In December of 1928, when he was visiting New York, he gave one of those solo performances at Carl Van Vechten’s apartment. One of the people who heard it there was Mabel Dodge Luhan, who commented, “This opera should do to the Metropolitan what the painting of Picasso does to Kenyon Cox.”5 Cox, who had been among the opponents of the Armory Show, was a portraitist and mural painter who had died in 1919. His academic style had won him great favor with the most conservative critics of his day. But the powers at the Met were not yet ready to be jostled from their Cox-like stance by the musical equivalent of Picasso.

Meanwhile, Henry Russell Hitchcock had heard bits of Four Saints in Paris. He raved to Chick Austin about it. Alfred Barr and Jere Abbott, who also knew it from jaunts to the French capital, concurred. That was enough for Austin. In the winter of 1932–33, he decided that the perfect event with which to inaugurate the auditorium of the new building would be the world premiere of Four Saints in Three Acts. So five years after Mable Dodge Luhan made her prediction, Thomson had occasion to orchestrate the opera.

From Thomson’s point of view,

Chick went ahead with the opera plan in the same way that he accomplished other things, not by seeing his way through from the beginning but merely by finding out, through talking of his plan in front of everyone, whether any person or group would try to stop him. Then once inside a project, he would rely entirely on instinct and improvisation. For he considered, and said so, that a museum’s purpose was to entertain its director.6

This time, there was no one to stop him. The local dancing schools—or for that matter the opera guilds—felt no threat from the production of Four Saints.

Not that the failure of the ballet in Hartford didn’t interfere. Chick originally intended to produce Four Saints “under the auspices of the American Ballet.”7 He expected Thomson to orchestrate some new ballets for Balanchine, and Balanchine to choreograph a ballet especially for Four Saints. It was only five months before the premiere that Thomson arrived in New York from Paris and upon walking into the Askews’ apartment discovered that the American Ballet Company had left Hartford almost as soon as it had arrived there. But Austin had already found a solution. For one thing, Eddie Warburg, who felt bad about how things had turned out for the ballet considering all the trouble Austin had gone to, gave five hundred dollars. The Sobys and the Askews and Jere Abbott also contributed generously, with the Julien Levys, the Alfred Barrs, the Paul Sachses, the Edward Forbeses, John Walker, and other people giving as well. And for most of his funding—the budget for the production was ten thousand dollars—Austin could count on the support of The Friends and Enemies of Modern Music.

Thomson had a lot of ideas about the staging, but needed a director. In November he met John Houseman at one of the Askews’ Sunday afternoons. Houseman was at that point an unsuccessful playwright, and had never directed anything, but Thomson recognized him as the person for the job. The next morning the composer got Houseman to go to his hotel room, where he had a piano. For almost two hours he banged away and sang arias, recitatives, and choruses in “his thin, piercing tenor voice.”8

He performed lines like the opening:

“To know to know to love her so.

Four Saints prepare for Saints

It makes it well fish.

Four saints it makes it well fish.”

In one passage Saint Ignatius sang about

“Pigeons on the grass alas.…

If a magpie in the sky on the sky can not cry if the pigeon on

the grass alas can alas and to pass the pigeon on

the grass alas and the magpie in the sky on the sky

and to try and to try alas and the magpie in the

sky on the sky and to try and to try alas on the

grass alas the pigeon on the grass the pigeon on

the grass and alas.”9

Houseman was convinced. When Thomson asked him to work on the production—gratis—the playwright accepted happily.

Together they set about to find a cast, rehearse, and coordinate. Thomson asked the artist Florine Stettheimer to do the sets. Wanting a good choreographer, he persuaded Frederick Ashton to come from London. The production had enough money for third-class fare. The Askews could offer a free bed. The only people who could be paid were the singers and the orchestra.

Thomson specified that the performers were all to be black. Contemporary newspaper accounts present both his reasons for this decision and their own startling evaluations of it. The Hartford Courant reported:

In the selection of a Negro cast, Mr. Thomson believes that he has overcome obstacles which otherwise would have lessened the quality of the performance in several directions.

Because of the libretto, it was highly essential to have English speaking singers. So great is the verbal or phonetic importance that it would never have done to employ singers to whom English pronunciation and phrasing was not native or instinct.

The choice of singers therefore was immediately limited to American or English. Mr. Thomson felt that the vocal characteristics of these nationalities—pure head tones, flutey but hollow—lack the sonority which is completely essential to the music. Through process of elimination, Negro voices were all that was left.

Thus far the selection of a Negro cast was negative. There was, however, an entirely positive phase to the selection.

The Negro voice is sonorous. Its diction, contrary to expectation, is clear and easy in enunciation. Moreover, the Negro is noted for real style in singing—the power of the race to throw itself completely into song, its traditional resort to song on all occasions, makes singing a national medium of expression, and one which has therefore by now been highly developed.

Then too, the Negro cast has no intellectual objections to the advanced nature of the libretto. Not once, said Mr. Thomson, has any member giggled over the arrangement of words—a condition which the composer believes he could not duplicate among any other singers. The completely serious, unbiased and non-self-conscious acceptance of the text on the one hand, and the natural clear enunciation on the other, enables the cast, in Mr. Thomson’s words, “to pronounce the words as if they did mean something.”10

To an interviewer from the New York World Telegram, Thomson explained, “Negroes have the most perfect and beautiful diction.… I have never heard a white singer with the perfect diction and sense of rhythm of a Negro.”11 Blacks represented both an ideal spontaneity and nonjudgmentalism for him. He had always liked Negro church choirs. Helped by a talent scout who specialized in black performers, he began to stage auditions in the Askews’ drawing room. After filling the lead roles, he went to Harlem to hear future choristers. Soon enough, he had assembled a cast. He also found Miss Eva Jessye—who had been training Harlem choirs for years—to work with them in her studio on the second floor of a local brownstone. Then for the final preparations Thomson and Houseman rented a rehearsal hall in the basement of St. Philip’s Episcopal Church on 137th Street.

Meanwhile there was no end to the sweeping generalizations made on the subject of this “all-Negro” cast. After hearing the actual performance in Hartford, Carl Van Vechten evaluated its effect as having been precisely what Thomson had anticipated:

There is a simplicity and a distinction about this singing, a clearness in the enunciation, a complete lack of self-consciousness in the involved and intricate action of the piece, which completely justifies his decision in this direction.… There is nothing Negro in the gestures or singing speech of this remarkable company. After ten minutes it is possible to forget altogether (unless you perversely prefer to pleasantly remember) that these are Negro singers.… I may say in all truthfulness that on few previous occasions have I encountered such a perfect mating of cast and work.12

If Lincoln Kirstein had written Austin that Negro ballet performers in Hartford would be “nonpareil,” from Thomson’s point of view they were just that:

The Negroes proved in every way rewarding. Not only could they enunciate and sing; they seemed to understand because they sang. They resisted not at all Stein’s obscure language, adopted it for theirs, conversed in quotations from it. They moved, sang, spoke with grace and with alacrity, took on roles without self-consciousness, as if they were the saints they said they were. I often marveled at the miracle whereby slavery (and some cross-breeding) had turned them into Christians of an earlier stamp than ours, not analytical or self-pitying or romantic in the nineteenth-century sense, but robust, outgoing, and even in disaster sustained by inner joy.13

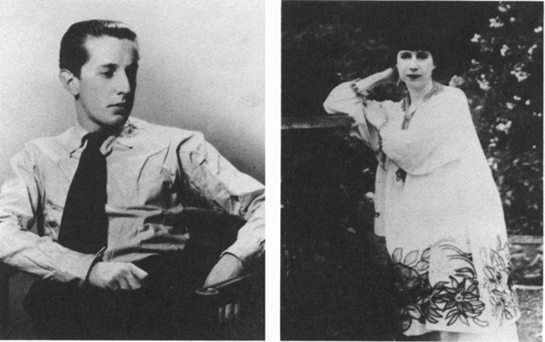

Four Saints in Three Acts in 1934. (Photo Credit 4.1) Below left: Frederick Ashton, photographed by Lee Miller, 1934. (Photo Credit 4.2) Below right: Florine Stettheimer, c. 1925. (Photo Credit 4.3)

Performance of Four Saints: angels dancing. (Photo Credit 4.4)

Here again the goals were naturalness and freedom from inhibitions. To be able to respond to one’s own instincts was far better than to bow to artifice and the imposition of form.

• • •

The presence of blacks was troublesome for Florine Stettheimer, however. She claimed that their hue threw off her color scheme, and asked that their faces be painted white. In this she did not prevail, although she did get the cast made up to an even shade of light brown, and put into white gloves. About most everything else, Miss Stettheimer got her way entirely. Saint Teresa wore crimson velvet, while the chorus was clad in long blue robes and silver halos. There were trees made out of feathers. A seawall at Barcelona was constructed from shells. The sky was made of fifteen hundred square feet of blue cellophane mounted on cotton mesh. For a procession scene there was a baldachino made of black chiffon, framed in bunches of black ostrich plumes. Joseph W. Alsop, Jr.—who had been graduated from Harvard in 1932, and whose father was a Hartford insurance executive as well as a prominent tobacco farmer with land next to Charlie Soby’s in the Hartford suburb of Avon—would report the effect from his first journalistic post at the New York Herald Tribune: “Two yellow cloth lions reclined before a sort of bower of cellophane, on either side of which two cellophane palms with magnificent cellophane plumes rose gracefully.”14

For the last three days of rehearsals, Miss Stettheimer and her sister Ettie stayed at Hartford’s elegant Hotel Heublein, as did Carl Van Vechten and his wife and Henry McBride, who was covering the event for the New York Sun. The cast, on the other hand, stayed in black households and those hotels where blacks were permitted. This was arranged by the Negro Chamber of Commerce, who also greeted the bus which transported the singers from New York. Thomson, Houseman, and other staff members filled the guest rooms of Helen Austin’s mother’s house.

The weather reached sixteen below zero. But everyone was too excited to care. During one rehearsal, Frederick Ashton grew so upset with Alexander Smallens, Leopold Stokowski’s assistant in Philadelphia and the conductor of Four Saints’ orchestra of twenty, that he stormed outside after exploding, “I have worked with Sir Thomas Beecham! A genius! And he never spoke to me as you have!”15 The temperature sent him right back in, though; nothing would stop this production.

The Avery Memorial officially opened on February 6, 1934. Four Saints in Three Acts had its “honorary dress rehearsal” the next night, and its world premiere on February 8. There was a program designed by Henry Russell Hitchcock, its shocking pink cover presenting both a poem by Richard Crashaw about Saint Teresa of Avila and a photograph of Bernini’s dramatic St. Theresa in Ecstasy. Inside was a musical portrait of Gertrude Stein by Virgil Thomson, a prose portrait of Virgil Thomson by Gertrude Stein, reproductions of painted portraits of both of them by Christian Bérard, and a reproduction of Kristians Tonny’s highly offbeat, elaborate portrait of Thomson. In addition there were startling photographs by Lee Miller of the opera’s directors and cast. Formerly an assistant and mistress to Man Ray, Miller was one of the regular Surrealist exhibitors at Julien Levy’s gallery. She revealed her subjects in telling ways. Chick Austin has his head cocked dramatically. John Houseman has that look of erudition that would later become his trademark. Frederick Ashton, wearing what must be the world’s widest, horizontal-striped tie, is the epitome of an inspired and intense choreographer. Virgil Thomson appears serious and intense to the core but sports a checked pocket handkerchief the size of a bistro napkin. There are also a number of members of the black cast, one face more richly beautiful than the next, all looking devout to the point of rapture. In addition, there was one photograph by Man Ray himself—provided by James Thrall Soby, who was working at that time on an album of Man Ray’s photos. It shows Gertrude Stein looking like an idol, someone who unquestionably knows everything.

The people who attended paid ten dollars a ticket. For the most part they were fashionable out-of-towners who came for the combination of the Avery opening, the opera, and the Picasso retrospective that Austin had arranged to coincide with these events. The New Haven Railroad added extra parlor cars to shuttle New Yorkers to these great happenings in Hartford. Mrs. Harrison Williams, considered one of America’s best-dressed women, had ordered a special dress that she could keep at cocktail length on the train and unfasten to full length for the reception and performance. Others who lacked such an easy means of switching from day to evening changed in the lavatories at the Heublein, conveniently en route between the Hartford train station and the Atheneum. Kirk Askew and Julien Levy didn’t object in the least to dressing in such close quarters, although Francis Henry Taylor—who a few years later would become director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art—thought far less of it. Standing in his gray flannel underwear he excoriated the “unfeasability of Chick.”16 But most people were thrilled to be there. When a shiny black vehicle “shaped like a gigantic raindrop”17 arrived at the museum itself, it deposited Buckminster Fuller flanked by Dorothy Hale and Clare Boothe in their shimmering evening gowns. The bizarre automobile was Fuller’s first Dymaxion car.

A sizable press corps also attended. There were critics from all over the East, and representatives from the major wire services. In many ways this was a national event. The society columnist Lucius Beebe gave a lengthy account in which he reported that “Since the Whiskey Rebellion and the Harvard butter riots there has never been anything like it, and until the heavens fall or Miss Stein makes sense there will never be anything like it again.”18 The opera was broadcast on radio throughout the country. Readers of the New York Herald Tribune were treated to Joseph Alsop’s account of the performance the next day. Of the introduction to Four Saints, Alsop wrote:

It made no sense in logic. Words were repeated, sentences were broken off and phrases kept popping back into the song like corks rising and falling in a bottle. Nevertheless, from the very first Miss Stein’s curious rhythmic verse, which the singing made more clearly audible than is usual at operatic performances, had an effect all its own. There were two or three bursts of laughter when the chorus, in long blue robes and diamond-studded gloves, repeated some especially startling phrase, but it was evident that a receptive audience liked the much-discussed words of the matron saint of art of Paris.

Alsop was as interested in the audience as in the opera. His report also covered the intermission following the first act:

The curtain went down on a finale with the phrase, “they never knew about it” for its theme, and the audience trooped into the foyer of the theatre to chatter, gaze at one another and talk of the play. Mrs. William Averell Harriman and her sister, Mrs. William Lord, discussed it in one corner. Henry McBride, critic, was not far off, next to a woman with heliotrope hair, who was congratulating Virgil Thomson. A. Everett Austin, Jr., director of the Wadsworth Atheneum’s Museum, to which the theatre is attached, and president of the Friends and Enemies of Modern Music, stood by a punch bowl, receiving congratulations. Alexander Calder, sculptor, turned out in a tweed coat and dusty boots, ignored the highly full dress appearance of the rest of the company. Carl Van Vechten, author of “Peter Whiffle”; Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York; and Mrs. Muriel Draper were scattered in the crowd. They all gossiped and smoked until the second-act curtain rose for a new revelation.

Of the second act, Alsop wrote,

The lighting, arranged by [Abe] Feder, bathed the set, on which all the saints this time were in white, in a special luminousness. With the light and the color and the form, at once complicated, amusing and lovely, the setting seemed to give the note for the whole performance. There were elements in it that were merely smart, and therefore valueless, and there were other things about it of deep charm.… The ballet of six young Negroes emerged for the first time in the second act, rather startlingly naked for so saintly a gathering, but quite effective enough to deserve St. Ignatius’s “thank you very much” at the end of their dance. The choreography of the whole opera, which was done by Frederick Ashton, ballet master of the Camargo Society of London, was an important part of the general effect. It, too, like the setting and the words, managed to be baroquely witty and handsome in one breath.

Alsop’s overall evaluation of Gertrude Stein’s text was that “they made no sense, yet sung they were lovely.” Discussing a sequence in which the key words are “magpie in the sky,” he wrote,

In print the excerpts from the aria seem incomparably silly, but sung its foolishness was forgotten, and the handling of rhythm and sound in it, that talent which Miss Stein has been able to pass on to Ernest Hemingway and Sherwood Anderson, had its full effect.

Not everyone in America was focused on the black tie opening of an experimental opera that day. While the society column set was descending on Hartford in parlor cars and limousines, Eleanor Roosevelt spent the day at a ceremony held at the Hotel Governor Clinton in New York. The event had originally been scheduled for the Waldorf-Astoria, but a strike of waiters and cooks had forced the change. She used the occasion to sew an NRA label to a straw hat and promise a “better day for all of us.” Joseph Alsop, for one, was cognizant of how rarefied the Hartford audience was. “What a less hand-picked public, less interested in smart art, will think of the production remains to be seen,” he wrote. Indeed, half a century later, Four Saints in Three Acts is not a part of the standard opera repertory. But at least to three hundred people for each of six nights in Hartford, Connecticut, and to subsequent groupings in Philadelphia and New York, these were rich pickings.

And for those of the inner circle, this was cause for celebration. There were dozens of curtain calls. Russell Hitchcock, smashing his opera hat and tearing open his shirt, got Austin to take a bow People applauded Virgil Thomson. And then the same crowd who had had cocktails at the Sobys’ before the performance repaired to the Austins’ afterward.

In the Rococo living room of the Palladian villa, Salvador Dali sat in a love seat next to Mimi Soby. Staring at the mother-of-pearl buttons on the bosom of her dress, he politely asked if they were edible. (“Madame, ces boutons, sont-ils comestibles?”)19 Nearby, Nicholas Nabokov—a composer who had recently fled Russia—banged out Russian folk songs on the piano while Archibald MacLeish and other guests sang along. Not everyone was quite so festive, however. Julien Levy waxed rhapsodic to Virgil Thomson, but Thomson would have none of it. “Oh dear, Julien, didn’t you notice that the trumpets came in a beat late at the beginning of the second act?” he complained. Replying “Oh, Virgil, don’t split hairs!” Levy gave Thomson “a small push” that sent the composer out of balance and into a fragile antique chair made of gold bamboo; the chair fell into splinters and Thomson landed on the floor. Sandy Calder—whose red flannel shirt had caused quite a stir among the black-tie crowd that night—saw all this. He enveloped Levy “in a tight bear hug” and, asking if he was drunk, carried the art dealer upstairs and put him to rest in a quiet bedroom.20

Shortly after, Carl Van Vechten wrote to Gertrude Stein to say, “Four Saints in our vivid theatrical parlance is a knockout and a wow.… I haven’t seen a crowd more excited since Sacre du Printemps. The difference was that they were pleasurably excited.”21 Van Vechten also wrote an essay entitled “How I Listen to Four Saints in Three Acts” that appeared in the souvenir program of the opera’s six-week run—the longest engagement to date for an American opera—at the 44th Street Theatre in New York. He recommended an approach to the performance that could apply equally to a session of psychoanalysis. “It is better to take your seat in the theatre where Four Saints is being performed without expecting or hoping or desiring for anything,” suggested Van Vechten. That posture of openness and receptivity was no small task. Even if a number of Van Vechten’s readers were in the habit of trying for it on their analysts’ couches, it was tougher to achieve in a theater seat. But the goal was central to what people like Warburg, Kirstein, Austin, and Soby were all working for in various ways: a willingness to approach experience unarmed.

This was the point of view Stein put forward in a radio interview she gave later that year:

If you go to a football game you don’t have to understand it in any way except the football way and all you have to do with Four Saints is to enjoy it in the Four Saints way which is the way I am, otherwise I would not have written it in that way. Don’t you see what I mean? If you enjoy it you understand it, and lots of people have enjoyed it so lots of people have understood it.

Of the “Pigeons on the grass alas” sequence, Stein explained,

I was walking in the gardens of the Luxembourg in Paris it was the end of summer and I saw the big fat pigeons in the yellow grass and I said to myself pigeons on the yellow grass, alas … and I kept on writing until I had emptied myself of the emotion. If a mother is full of her emotion toward a child in the bath the mother will talk and talk and talk until the emotion is over and that’s the way a writer is about emotion.22

Carl Van Vechten wrote of the Four Saints performance, “If the auditor demands a plot, he will be disappointed, but why should he demand a plot? It is like looking at a painting and demanding a story.” An approach free of the usual demands and expectations would reap rewards. Astute listeners could enjoy “the great skill with which Virgil Thomson has written for the voice, following its natural inflections so instinctively that the music proves to be more consistently singable than many other operas written by the most celebrated composers. Miss Stein’s words always sound better than they look.” Moreover, “to compensate for the lack of story in the accepted sense, there is abundant action, action which is witty, beautiful, suggestive, and full of entrancing double meanings.”

By suspending old-fashioned, traditional criteria and by allowing oneself to revert to primary instincts, there was a new access to the enchantment of unexpected truths. The requisite was the deceptively difficult feat of relaxation and of letting down one’s guard.

If you will lounge in your chair and permit the words of Gertrude Stein, the music of Virgil Thomson, and the imaginative action of Frederick Ashton against the extraordinary decorations of Florine Stettheimer, to sink into your consciousness, play as they will on your emotions, you will perhaps find yourself, to your own surprise, actually enjoying this strange work of art, enjoying it very much indeed, in fact.

Van Vechten was among those proponents of modernism capable of such pleasure: “The performance of Four Saints,” he concluded, “is just about as perfect as would seem humanly possible.” The benefits of an open mind and relaxed posture were vast.

To some people the Four Saints premiere marked a change in the course of Western civilization. However, at least one person considered it with a different historical perspective.

Agnes Mongan felt a distant connection with Gertrude Stein, who had been a Radcliffe classmate of Paul Sachs’s sister. In a review she later wrote of Stein’s book on Picasso, Mongan pointed out that Stein’s deliberately tendentious approach always achieved the author’s goal of “an aroused, alert, attentive reader.”23 That awakening was a worthy goal. Thus Mongan could write Austin a perfectly correct, tactful letter about the premiere: “All of us who were at your historical opening agree that we have never had better fun. It was a grand two days. Your stage setting for the whole was superb.”24 Yet this was short of the gusto with which Mongan might describe a Poussin sketch. Even if the Stein-Thomson opera made for a nice occasion with “the old gang”25 from the Fogg, she did not regard it as the same apotheosis they did. The person to whom she confessed this reserve was her mentor Georgiana King. G.G. had of course known Gertrude Stein since before Austin and Hitchcock were born, and had periodically reviewed Stein’s books. But like Mongan she was immersed in the culture of previous centuries, and from this vantage point might sympathize with Mongan’s view that what was an amusing adventure was not much more. So on February 15 Mongan—who rarely wrote to her former teacher—suddenly poured out her heart to “Miss King”:

The Hartford opera was great fun. I would not have missed the opening for anything less than pneumonia—but I did miss, even though I followed it intently, the significance of many things. I wish you had been there. Certainly you would have known how seriously Miss Stein intended it to be taken. I was content to have it a Baroque conceit, as I heard it called, until a bright young man whom I asked about “There are pigeons in the grass, alas, there are pigeons in the grass” said in superior tones, “Why that is the whole of Spanish iconography.” If his answer was correct there are things you did not teach us about Spain, Miss King, or else I was sadly lacking in attention.… The scenery, all wrapped in cellophane, glittered and shone in the shifting lights. Yet in the end I wondered how it would fare in New York as a professional production. The whole thing seemed to have the gaiety and intimacy and spontaneity of an amateur performance done in the presence of sympathetic friends. That was largely the reason it was such great fun to see and hear it. Edward Warburg doesn’t in the least agree with me. You may hear his opinion when he lectures at the Deanery [at Bryn Mawr], as Miss [Charlotte] Howe tells me he is going to do.26

Meanwhile, the other key event of the Avery Memorial opening presented artworks of more certain long-term significance. Mabel Dodge had said that Four Saints in Three Acts would do to the Metropolitan Opera what Picasso would do to Kenyon Cox. Stein and Picasso were thought of in tandem back then. The Avery auditorium had opened with the sort of modern music and modern writing guaranteed to put stalwarts of tradition on their ears; its exhibition space naturally had to be launched with art that was equally new and audacious. Picasso’s paintings were the answer. Like Stein’s and Thomson’s collaboration, not only were they pioneering, but they also represented the hotbed of creativity that was centered in Paris at the time.

A Picasso retrospective was a wise choice to show to advantage the interior court of the new Avery Memorial. The building’s exterior, in deference to its donor’s wishes, was of the same marble and bronze as the adjacent Morgan Memorial, and compatible in style if updated in tone. The interior, however, was pared down and streamlined. The aesthetic advocated by Philip Johnson and Henry Russell Hitchcock had made its mark. The cantilevered balconies over the Avery court were clean and fresh uninterrupted expanses of white plaster. The bold architecture called for daring, forthright art.

The courtyard had a lean but adventurous display of recent sculpture. There was Brancusi’s Blonde Negress, lent by Philip L. Goodwin, as well as a number of pieces that Eddie Warburg provided, among them the little wooden Gauguin and works by Epstein, Lachaise, and Lehmbruck. Upstairs on the second-floor balcony and in galleries paneled simply in pine, the Wallace Nutting Collection of seventeenth-century American furniture and objects was put on view to rare effect by Henry Russell Hitchcock. These rough-hewn pieces dramatized life in an era when experience had of necessity the immediacy and high pitch that many modernists were now seeking by choice. There were two other loan shows: “French Art of the Nineteenth Century” and “Museums One Hundred Years Ago”—an exhibition of photographs and plans also organized by Hitchcock. But the real drawing card was the Picasso exhibition, which was on the third-floor balcony and in the adjacent large exhibition room.

Picasso had had solo shows in America before, mostly in New York. The first was in 1911 at the 291 Gallery. Then came a 1914–15 show at the Photo-Secession Gallery, and in 1923 an exhibition of his new “neo-classic” works at Wildenstein. The pace had stepped up at the end of the 1920s and beginning of the 1930s, with fairly regular shows—mostly of drawings and gouaches—at the John Becker, Reinhardt, Demotte, Marie Harriman, and Valentine galleries. But these were all private gallery exhibitions of work for sale. The only nonprofit institutions to do solo Picasso exhibitions were the Chicago Arts Club—with two small shows in 1928 and 1930—and the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, where Picasso’s work had been shown in both 1931 and 1932. The Atheneum’s Picasso exhibition was in a different league altogether.

There were seventy-seven paintings, and an equal number of prints and drawings. The oils ranged from the small 1895 Mother and Child to some of Picasso’s most recent work, like the enormous 1931 Large Still Life from Paul Rosenberg’s collection in Paris and the 1932 Woman Before a Mirror. As part of the collection of the Museum of Modern Art this painting would eventually become synonymous with the artist’s name, but in 1934 it was still in Picasso’s personal collection and largely unknown.

The Atheneum’s show put on public view for the first time a number of paintings that have since become widely familiar—reproduced on cards, posters, and T-shirts, and in countless Picasso books. Many of these artworks would again be seen in the Museum of Modern Art’s major Picasso show in 1939 and in scores of subsequent exhibitions, but prior to 1934 they had been available only to a small and exclusive audience. Lent by some of the most adventurous, prescient American art collectors and galleries of the era, these paintings and works on paper showed all Picasso’s major developments to date. Adolph Lewisohn provided the brushy and Impressionistic Courtesan with a Hat from 1901, the same year as Dr. and Mrs. Harry Bakwin’s Fille Au Chignon and M. Knoedler & Co.’s At the Moulin Rouge—three paintings that showed Picasso still under the influence of Toulouse-Lautrec and absorbed with music hall life. From the year 1903 came some of the most evocative portraits of the artist’s Blue Period: the Art Institute of Chicago’s Old Guitarist, Jere Abbott’s Les Misérables, and A. Conger Goodyear’s Vieille Femme. Felix and Frieda Warburg may have thought that Picasso’s Blue Boy belonged on the squash court, but the Wadsworth Atheneum was more than happy to have it on view for a second time and to reproduce it in the catalog along with other 1905 landmark works like Sam and Margaret Lewisohn’s The Harlequin’s Family, Mr. and Mrs. William Averell Harriman’s Woman With a Fan, the Marie Harriman Gallery’s Woman Combing Her Hair, and La Toilette—the painting that had cost Conger Goodyear his relationship with the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo and hence freed him for the Museum of Modern Art. It is hard to imagine a group of pictures that could better convey the blend of Picasso’s classical grace and tranquillity with an indefinable mystery.

A. E. Gallatin lent a 1906 Self-Portrait with boldly chopped-out features that attacked the issue of human appearance in an entirely different way from the work of the preceding year. The Marie Harriman Gallery and the artist George L. K. Morris supplied Cubist still lifes. Paris collectors lent generously as well. The Baron Fukushima provided various major works, including the wonderful 1919 Sleeping Peasants. Alfred Barr would eventually call this small colored ink and crayon drawing of two exhausted lovers in the hay “one of the earliest and most memorable of Picasso’s compositions in the ‘colossal’ style”; today it is one of the artist’s most popular works at the Museum of Modern Art.27

Pablo Picasso, Sleeping Peasants, Paris, 1919. Tempera, watercolor, and pencil on paper, 12¼ × 19¼. (Photo Credit 4.5)

Another work that would in time become a focal point at the museum and that Barr came to regard as one of the two paintings “which are perhaps the high point of synthetic cubism” was the 1921 Three Musicians lent by Rosenberg.28 Other key works of the same style had come from nearer by, like the large The Table that was at Smith College. The Atheneum show was also rich in paintings from Picasso’s neoclassical phase. There was Philip Goodwin’s 1920 gouache The Rape, Pierre Matisse’s 1921 Legend of the Source, and a range of canvases that measured at most six by eight inches each but loomed large. These included the Atheneum’s own 1922 Nude Woman, Mr. and Mrs. James Thrall Soby’s 1923 Mother and Child, and Maternité and Jeux Familiaux—both from the artist’s own collection.

The curvilinear Cubism of the 1920s was represented by a range of large and important canvases lent by the Sobys; by the Wildenstein, Valentine, and Becker galleries in New York; and above all by Paul Rosenberg in Paris. There were also some fairly disquieting works from the later 1920s: the Sobys’ Seated Woman, a large canvas that belonged to the New York collectors Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Janowitz, and more paintings from Rosenberg. And bringing it all up to date there were some paintings from the artist’s Surrealist phase. These ranged from A. E. Gallatin’s playful 1929 Bathers at Dinard—a remarkable small canvas that showed highly abstracted figures in striped bathing suits ecstatically throwing a ball on the seashore—to an unsettling 1929 Composition depicting a head that is a unique assemblage of forms closely related to various elements of male and female genitalia. One can hardly imagine what the local insurance executives and their wives made of these recent canvases in particular. For people to whom the seashore meant martinis on the veranda, and dreams meant something you didn’t talk about at breakfast, the Surreal phase was the most startling of all.

This first solo Picasso exhibition in a major American museum evoked little of the hoopla begat by the Four Saints premiere. Newspapers mentioned it, reviewers and the public attended, but there was no significant outcry. None of the major national magazines gave the show any attention at all. Nor were the newspapers especially engaged. The New York Herald Tribune did not deem it worthy of a separate review. Joseph Alsop mentioned it briefly at the end of his big February 8 piece on Four Saints, calling it “an exhibition of Pablo Picasso which experts concede to be the finest ever arranged of the great modernist,” but he treated it essentially as a news item, significant mainly because of its comprehensiveness and the distance the paintings had traveled.

In The New York Times, comment on the Picasso show in Hartford was confined to a short article in the lower-left-hand corner of page twelve of section nine that same Sunday. Ambiguously titled “It Makes it Well Fish” it would have attracted the attention of only the most assiduous of readers; it certainly did not appear to be an exhibition review. “It Makes it Well Fish” was Edward Alden Jewett’s take on all that had happened at the opening of the Avery. He was amused by Four Saints, although he called it a “succès fou” and pointed out that “Cellophane is only cellophane and a museum is for the ages.” As for the Picasso exhibition, it warranted one paragraph, predictably condescending toward abstraction and sided toward the artist’s classical, nonconfrontational phases. Equally predictably, the text included the names of the more prestigious lenders—as if this was what was necessary to give the event a bit of clout. It wasn’t negative, nor was it much else. What received far more notice in all the papers that day were Orozco’s new murals at Dartmouth College and a big Prendergast show at the Whitney; these were the paintings reproduced when Picasso’s were not considered deserving of illustration.

The one New York critic who did the show justice was Henry McBride. Unlike his counterpart at the Times, he did not wait until a couple of weeks after its opening to bother to mention it. While the other papers relegated Picasso to a position of little significance in spite of all the attention they awarded to Four Saints, McBride’s coverage in the February 10 New York Sun dignified the Picasso show as a significant event. He made much of the new building and the opera premiere, but his general take was that the Picassos were “the whole thing of the occasion.”

The Picasso show had other champions among the small circle already committed to modernism. Austin and Soby lectured around town and at the exhibition itself, trying to drum up enthusiasm. The specialized art press gave the show attention. The Art News put a large reproduction of one of the paintings on its first page and reported that this was “an occasion not to be missed at any cost.” Its critic said that there was no “parallel in Western art for line such as one finds already in ‘Garçon Blue’ from the collection of Mr. E. M. M. Warburg,” referred to the “amazing” solidity of form of Woman Combing Her Hair, and credited the small neo-classical canvases with “a monumentality that is amazing, and the intensity of old masters.” She was less enthusiastic about Picasso’s recent art—the 1929 works were “empty of meaning,” and “regarding those of 1932 even less can be said”—but at least she cared enough to comment.29

The occasional visitor, too, was deeply moved. The person with whom Agnes Mongan had driven down from Boston for Four Saints and the Picasso opening was Nathaniel Saltonstall, a Boston architect who was a trustee of the Museum of Fine Arts. On the way back Saltonstall told her that they really ought to be doing the same sort of thing on their home territory. He later spoke with his mother about the possibility of a fund-raising performance on behalf of a new organization to advance contemporary art. She offered the use of her drawing room overlooking the Charles River for a concert. Saltonstall knew just the person to give it—a bright young friend of his, a Harvard undergraduate who played the piano beautifully. And so Leonard Bernstein’s first public performance was arranged.30 It helped to launch a Boston branch of New York’s Museum of Modern Art—the Boston Museum of Modern Art—which initially held exhibitions at the Fogg and at Harvard’s Germanic Museum. To a degree this organization tried to pick up where the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art left off. Soon to evolve into the Institute of Contemporary Art, it opened in 1936 with Saltonstall as its president, and Alfred Barr, Paul Sachs, and Mongan on its board. The first director was James Sachs Plaut, a nephew of Paul Sachs who had been on the staff of the MFA and felt inhibited by its strictures against buying or showing the work of living artists.

But not everyone got the message. A contemporary account of the Hartford exhibition reported

Confronting one of Picasso’s abstractions one hears a conversation rather like this: “Is or is that not a chair? Is somebody sitting on it? This must be a man because the title says so.” And finally the spectator finds himself furious with both himself and Picasso because he has been wasting his time on unimportant matters.31

This was the dominant American view, captured above all by Thomas Craven, whose widely read book Modern Art was published three months after the Atheneum’s Picasso show. Craven’s views on Picasso represented majority opinion in America in 1934:

This small, sly, uneducated Bohemian is the king of modern painting; by common consent the master of the modern School of Paris. And a master he is—but not of art. He is a master of methods.

Picasso’s career is a masterpiece of strategy.…

Bothered by no deep convictions which try the souls of bigger men, he has patiently cultivated the enigmatical … His art is perfect because it offers nothing; pure because it is purged of human content; classic because it is dead.…

His subjects … are artificial forms manufactured in the studio; they are devoid of vitality and meaning; they have no basis in the observed facts of life, or in the behavior of man. He uses a stock expression for all faces; his figures are all alike—all concepts, curiosities, isolated trash. There is not, in the whole lot of them, a single convincing human being.…

Picasso’s cubes and cones—give them as many titles as you please; disguise them, if you can, by esoteric riddles and psychological balderdash—remain cubes and cones, congested particles of dead matter.…

Picasso is a perfect specimen of the artist reared in the atmosphere of an international Bohemia. He is neither Spaniard nor Frenchman; his art reflects no environment, contains no meanings, carries no significance beyond the borders of the Bohemian world of its birth. The content of his art, where any is to be discerned, pertains to those vague generalities by which youth unconsciously betrays its ignorance of life.32

A year before this publication came out, Lincoln Kirstein had written to Agnes Mongan, “I am pleased to get Craven sore, if possible, for he is such a son of a bitch.”33 On the other hand, a lengthy review in The New York Times Book Review legitimized Craven as a writer by comparing him to Thomas Dewey in his cry for living experience as the content of art.34 In a major front-page piece in the Herald Tribune’s Sunday Book Review, Frank Jewett Mather, Jr., called Craven’s book “a much needed tract for the times.”35 Closer to home for Chick Austin, the Hartford Courant devoted an unusually extensive piece to Craven’s book, endorsing the critic’s diatribe on the sort of people who supported Picasso:

On the whole our museums are gilded show places stuffed with inferior old masters and directed by soft little fellows from the Fogg factory who use pictures to titillate mischievous erotic appetites. Some of them support little communities of retainers, traders, esthetes. They cater to tail coats, bored women, and kept radicals.36

Those who bought and showed Picasso at that point in history might congratulate one another, but opprobrium and mockery were still what they could expect from the public at large.

Like Philip Johnson and Eddie Warburg, Jim Soby didn’t mind working without pay, and became honorary curator of modern painting and the librarian of the Atheneum. Austin had limited funds for loan shows, but often he needed to do nothing more than walk down the hall to ask Soby to lend his holdings. From May to October of 1934, the Atheneum did its third show of the Soby collection. By now there were four Picassos: the diminutive Mother and Child and Bather, and Le Soupir—all from 1923; and of course Seated Woman. The count of Derains was currently at four. Above all, there was now a surfeit of the neo-Romantics: thirteen paintings and six drawings by Eugene Berman, and works by Bérard, Léonide, and Kristians Tonny. In October, Jim Soby provided a different exhibition entirely—his collection of photographs by Man Ray—about which he had recently completed a book.

Things were lively at the Museum of Modern Art as well. Philip Johnson put on an exhibition called “Machine Art” that consisted of kitchenware, lighting fixtures, adding machines, gasoline pumps, springs, propellers, and other machine-made objects. Josef Albers, from his studio at Black Mountain College, helped design the catalog cover. In 1933 Eddie Warburg had become chairman of a committee to study the possibility of a film library at the museum, and the following year they arranged a showing at the Wadsworth Atheneum of films made between 1914 and 1934. The program, prepared by Iris Barry, who was the Modern’s librarian, was a success. The Modern organized similar programs elsewhere and decided to establish its Film Library, run by Barry, with John Hay Whitney as its president and Warburg as its treasurer.

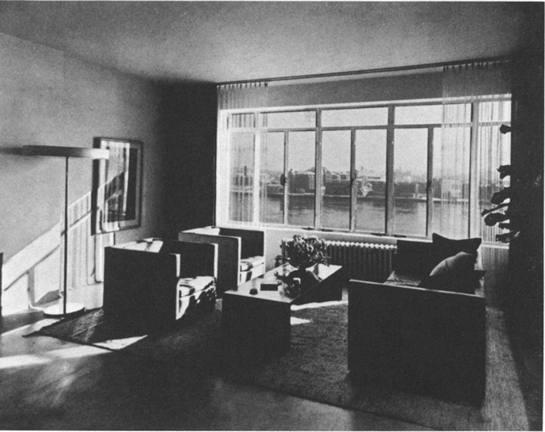

The School of American Ballet was also moving forward. Kirstein ran the show, Balanchine instructed, and Warburg kept an eager band of journalists supplied with information on the ballet’s progress and purposes. In addition, Warburg had commissioned a new home for himself. For this he had turned to Philip Johnson. Johnson was not an accredited architect; in fact he had never before designed anything for a client. But it was clear from what he was doing at the Modern that he knew a lot about architecture and design, and Warburg admired and liked him.

It’s no surprise that by the end of 1933 Warburg was beginning to feel he needed a space of his own. Even if he would have to keep Dynamo Mother in the closet wherever he lived, he needed a more sympathetic setting for The Knees and Breasts than the squash court at 1109 Fifth. Johnson found him a fourth-floor walk-up in an old brownstone on the river side of Beekman Place. He told Warburg they should wreck it completely and start all over again. Where there were two small windows overlooking the East River there should be a wall of glass. Every last drop of ornament had to go. If at 1109 Fifth Avenue Warburg was used to rugs on top of rugs, now he would walk on linoleum. Instead of brocades and velvets, the draperies would be fishnet.

Besides their major exhibition, Johnson and Hitchcock had also written a book about the new International Style. Johnson’s own first apartment, around the corner from Warburg’s at 424 East Fifty-second Street, had been designed by Mies van der Rohe and executed by Lily Reich. The lines were spare and elegant, the atmosphere assertively modern. There were Barcelona chairs, solid raw silk curtains, Chinese floor matting, and austere metal lighting fixtures. Then, early in 1934, Johnson designed a duplex for himself and his sister. There and in Warburg’s rooms on Beekman Place, he tore out many of the interior walls of the existing apartment, put down pale ecru linoleum, and focused on the beauty of severe, solid planes at right angles to one another. Rooms had more than one function—a dining room in the living room, a bedroom–sitting room—and everything was physically and visually light. Johnson was violently against surface decoration of any sort. He selected everything for his client, and kept it all as lean as possible. Along with furniture designed by Mies, there were Johnson’s own pigskin-covered bucket chairs and sofa, his tubular wastebasket, two of his lamp designs, and the fishnet curtains, all arranged with utmost rigor.

The Warburg apartment was a bold statement. The lack of ornament was a self-conscious assertion of the patron’s sense of his own progress. The visual austerity suggests that he could do without what was silly and superfluous. Both Johnson and Warburg were fully aware that this radical aesthetic would shock others, but that was part of the thrill. They were extolling frankness both in what they chose and what they rejected, and they knew the effect it would have. Wishing desperately for change, they achieved it in the declaration of their aesthetic difference from their families.

There is, however, an unresolved attitude toward luxury in Warburg’s apartment. Adolf Loos, the Viennese architect, had at the beginning of the century put forward the view that ornament represented wasted effort and wasted material, and hence the unnecessary use of capital. The new simplicity, as it was first conceived, was intended as a vehicle for economic saving. In fact, part of what Warburg’s family would find offensive at 37 Beekman Place was the frugality that the visual leanness suggested. But this austerity, in fact, was high-priced custom work. What was deliberately spare and saving was—in this incarnation of the new simplicity—also quintessentially luxurious. There may have been exposed radiator pipes, but there were also those slabs of the perfectly buffed ebony that had been imported at no little cost from Indonesia. There may have been fishnet curtains, but other coverings were raw silk. And the unencumbered setting was a stage for some very fine art objects: a bronze by Jacob Epstein, Lachaise’s marble Knees, Picasso’s Blue Boy—which at least to some people was already a treasure.

From Johnson’s point of view, the young museum trustee was an ideal client. Warburg made no demands. He never asked either about the schedule or the cost.37 This was very much the approach Warburg advocated at museum board meetings; if you believed in the people you had hired, you should do everything within your power to nurture and support their creativity without interfering. To trustees like Sam Lewisohn, who at times carried on like frustrated museum directors, he screamed an unpopular “hands off.”

Johnson was still unknown, his ideas unproven. Warburg’s willingness to give him a start overwhelmed him. “How did he know what I would do? I had never had a commission before. But he trusted me, just as his father trusted him. Eddie has a great sense of style and of patronage. He knew that he was supporting an up-and-coming artist, and he took a big chance.”38 So he went along with that exposed radiator, the unframed mirror with clips, and the frankly industrial furniture. They appealed to him in the way that Calder’s wire figures and Blue Boy did: they were utterly direct and to-the-point.

Felix Warburg, as usual, did his best to be gracious. At risk to his failing health, he climbed the three steep flights to visit. He tried to like the austerity of the two rooms. But a few minutes after Fizzie arrived, he leaned over to use the phone, and as the metal strap runners of the desk chair slid out from underneath him, his jaw crashed onto the desk. When Eddie rushed over to help, his aging father simply said, “That’s what I like about modern art. It’s so functional.”

Eddie himself had mixed feelings about the place. The Macassar ebony screen walls were beautiful to him, as were the birch dining table and the black lacquer coffee table. The neutral colors and overall simplicity made a striking setting for the art. The view was wonderful. For five years he would live well with the combined living and dining room; central core with kitchen, bathroom, and closets; and the bathroom/study. But the pigskin chairs often gave their occupants a mat burn. And “it was a bit monastic for me. I was uncomfortable with the coldness of it … I always felt that when I came into the room I spoiled the composition. The discipline was so violent. If you moved an object an inch, it threw everything off kilter. If a magazine was not at right angles with the coffee table, you felt that the room hadn’t been cleaned up. Acoustically it was awful. You dropped a spoon on the table and thought a pistol shot had gone off.” Yet he admired the visual grace and fine proportions as well as the textural play. And it pleased him to be, for Philip Johnson, “an angel.”

The living room of Edward Warburg’s apartment on Beekman Place. House & Garden, January 1935.

Dance rehearsal at Woodlands.

The March 15, 1934, Town & Country told its eager readers that “the classes which everyone in New York seems to want to watch” were those being conducted by George Balanchine under the auspices of the “two young Harvard graduates who have made their mark in the arts.” But Eddie Warburg could think only of expenses. The descendant of two of America’s greatest financial families found himself struggling with bills for tutus. They were indicators of the master’s current state of health. When Balanchine, who had had tuberculosis, was feeling frail, he would have the dancers lie down on the floor a great deal, covering their tutus with sticky rosin in the process. When he was heartier he would have them jump around—which kept their tutus clean. Warburg was pleased to save on the cleaning bills.

The first place to see the new ballet company in full performance was at Warburg’s twenty-sixth birthday party. In its first few months, the company had developed three ballets, all choreographed by Balanchine. Two of these—Mozartiana and Dreams—were revivals of works that had been staged in June of 1933 by the “Ballets 1933” at the Champs Elysées Theatre in Paris. The music for Mozartiana was Tchaikovsky’s arrangement of a minuet, the Ave Verum, and a theme and variations by Mozart; the costumes and decor were by Christian Bérard. Dreams had music by George Antheil and “themes and costumes” by André Derain. The other ballet, Serenade, was an entirely new piece danced to music by Tchaikovsky. All of these works needed a trial presentation in America.

Woodlands seemed the perfect place for that first performance. Eddie’s birthday in June would be as good an occasion as any. After all, there was very little that Frieda and Felix wouldn’t do to keep their youngest son happy. If a herd of Guernseys and a cowherd were required for their children’s milk, then a full-scale ballet premiere and dinner for 250 people—and a repeat event the next night when the first was rained out—were in order for Edward’s celebration.

Fizzie had taught his sons to dance by putting on a Victrola record and kicking their feet from under them to get them in time with the music. So why not have a dancing party—even if the steps were made by others? Amusing parties were a family tradition. In 1898, when Frieda Schiff had turned eighteen, her parents gave a celebration at which Walter Damrosch, standing in a tin tub full of water, sang a parody of Wagner’s Rhine Maidens.39 When Felix and Frieda had celebrated their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary in 1920, a silver-coated oak tree had been built in the gold room at 1109 Fifth; it was covered with silver acorns, each of which opened to a different photograph of the five children. The Warburgs didn’t care so much for masked balls or the usual society parties, but milestones in the family could not be celebrated too grandly.

No tin tub would do, of course, for the American Ballet Company. Dimitriev designed a bare pine dance platform that was built in a half-circle of lawn framed by cedar trees. Frieda and Felix agreed that the lawn could always be replaced. It was a perfect spot—at the bottom of a gentle slope from the rambling half-timbered multigabled house. Some of the audience could sit on cushions on the grassy bank. Others could watch from the flat lawn at the top of the hill. For this space the Warburgs borrowed folding chairs from the nearest undertaker, just as Jim and Mimi Soby had done for their showing of L’Age d’Or. The swimming pool changing rooms became dressing rooms for the seventy-five dancers who arrived by bus. Spotlights were put in the third-floor dormer windows, and Stein-way pianos concealed in the bushes.

The event was scheduled for June 9. Mozartiana went perfectly. But then came Serenade. This ballet seemed almost destined for trouble. In rehearsal the piece had had one sequence with all arms stiffly raised in a way that had reminded Warburg so strongly of a Nazi salute that he had had to persuade Balanchine to change it. Now, at the birthday party, just after Tchaikovsky’s music began and the dancers raised their hands heavenward for the opening, the clouds burst.

The crowd was not easily daunted, however. A few people threw some tarps down on the stage, and everyone headed inside for dinner. Eddie’s relatives mixed easily with guests like David Mannes, Malvina Hoffman, e. e. cummings, Muriel Draper, Paul Draper, Agnes Mongan, and Philip Johnson. Then Lincoln Kirstein suggested to Eddie’s parents that they continue the event the next night. Houseguests repaired to the sleeping porches, and the dancers took their bus back to Manhattan. Frieda consented to come up with another dinner for 250, and everyone else agreed to return the next day.

The next morning, however, nerves failed at breakfast. Eddie suddenly became anxious. Desperately eager to talk with Kirstein, he ran around crying, “Where’s Lincoln?” It was Agnes Mongan who heard Eddie’s brother Fred sally, “Booth shot him.” But whether nervous, mocking, or undaunted, everyone pulled through; Frieda’s purveyors came up with a second meal, and the American Ballet Company again tried its demonstration-debut, this time completing Serenade and Dreams as well as Mozartiana. Balanchine’s choreography introduced a new form of beauty to its young American audience.

Not that the new ballet company would ever enjoy an event entirely devoid of problems. While Eddie’s guests were filling their plates at two nights of buffets in the dining room, the cast was fed in the garage. A cinder-block construction heated and attached to the main dwelling, this structure was in fact one of the rare features of Woodlands—a first of its kind, and initially an anomaly for the insurance company, which hadn’t wanted to cover a house with a gas-powered engine within its walls. But in spite of this uniqueness—and although Frieda had done the place with style: red, white, and blue bunting; flowers and candles everywhere—Dimitriev was not impressed. According to Kirstein, Balanchine’s manager performed “one of the grandest denunciation scenes since Chaliapin’s in Boris Godunov. Were artists to be fed like pigs in a barn? He had known we were dilettantes with no comprehension of art, but were we under the gross illusion that good artists were serfs to be served in a filthy stable?”40 This was just the start of Dimitriev’s many furies.

In spite of such problems, from most viewpoints the American Ballet premiere was a success. It looked as if the new company might really get off the ground. Eddie Warburg agreed to cover in advance the expenses of the next six months as well as an additional eight thousand dollars “for costumes and scenery for future ballets.”41 A public debut for the American Ballet was the next step. And what it required was a new ballet with a uniquely local and current theme.

Warburg and Kirstein had said from the beginning that it wasn’t enough to use the word “American” in the name of the new ballet company and to employ American performers; they needed contemporary American subject matter. A fan of Owen Johnson’s Stover at Yale and Ralph Henry Barbour’s tales of college life, Warburg opted for 1920s stadium life as the theme of a new ballet for which he wrote the book. He named it Alma Mater—literally “nurturing mother”—and hence well suited to his tongue-in-cheek attitude toward the rah-rah set. The ballet would be a ludicrous parody of the world dearest to Ivy Leaguers. The main characters would be a punch-drunk halfback and a dizzy young woman who wore striptease-style panties under her Salvation Army uniform. The way in which teams had posed against the old Yale fence for sepia photographs thirty years earlier would set the style. Dancers would move from huddles to maneuvers on the field. The men would wear raccoon coats, or shoulder pads under Yale sweaters of the type Sandy Calder had donned for his Circus performances. The women would be stylish flappers.

Warburg and Kirstein picked John Held, Jr., to do the costumes for the young football crowd. They could hardly have latched onto someone better able to evoke the American 1920s style they wanted to satirize. Up until the stock market crash, Held had been one of the most successful popular artists in the country. He had illustrated the 1922 edition of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tales of the Jazz Age. His drawings for Vanity Fair and The New Yorker had helped fix the look of the era. In 1925 Held had made the cover of a “Football Number” for the issue of Life magazine that came out on November 19—just in time for a Yale-Harvard game of the type that was the butt of Warburg’s parody. The cover presented a flapperesque cheerleader. Her long strand of pearls is flying, her dress stretched tight, her garters at her ankles. Holding her heavily lipsticked mouth as wide open as possible, she is shown to be shouting “Hold ’Em.” Two years later Held illustrated the program of a Yale-Princeton game. He knew the types that Alma Mater was all about.

By the time Kirstein and Warburg approached him, however, Held was off his pedestal. He had lost a fortune in the stock market crash and suffered the breakup of a marriage and the effects of a bad horse-riding accident. The former rage of the twenties was now living in relative seclusion at the Hotel Algonquin in New York. He was pleased to get a job, and made the most of it. In addition to putting one key character in the classic raccoon coat—the production simply borrowed Eddie Warburg’s, so it didn’t cost them a thing—he gave the fellow a white boater with a broad blue band into which an oversized blue feather was stuck. The feather brandished a large white Y. Held captured that uniquely American way of flaunting one’s alma mater that can make well-educated and otherwise rather tasteful people resemble a cross between a billboard and a savage. He gave the Ivy Leaguers the look of the most maniacal alumni who totter through the streets of New Haven on reunion weekends, discarding their usually conservative attire for all the style and subtlety of the souvenir nut dishes sold at the local eating clubs. If Eddie Warburg and Lincoln Kirstein never quite fit in with Ivy League stereotypes, now they would mock them as well as shock them, with John Held, Jr., their perfect accomplice.

Held’s watercolor sketch for the villain of Warburg’s story shows the fellow with a bright red face. He may have picked up the color sitting in the stadium on a windy day. But more likely his broken corpuscles came from overimbibing from his hip flask. The man looks a total dolt. He is no more animated than a hat rack: his hands entirely limp, his legs straight sticks, his neck a narrow twig supporting his massive globelike head. The hat, which is too small, is squashed in place, while the oversized coat dwarfs the rest of his body. He is the ultimate foolish and ineffectual “Old Blue.”

Held also did a telling sketch of the Salvation Army girl over whom the halfback and villain will do battle. Her vermilion lips are painted even wider than those of the cheerleader on Life’s football number. On one level, however, she is the image of propriety. She wears the full-brimmed bonnet and long modest skirt required of her station. But the skirt has a deep slit in it. Red garters and brief lacy underwear are in plain view. This is exactly the way that Warburg and Kirstein saw the world: nothing is as it appears to be.

Held depicted people either as ambivalent or with singular characters grossly exaggerated. His bridesmaids for Alma Mater are the bridesmaids to beat them all, with dainty white gloves and enormous hats. His photographer is the quintessential photographer of the time period: a short character in baggy striped pants, frantically working his camera. His “boy babies”—the halfback’s children—are the ultimate Ivy League offspring, their nightshirts flaunting enormous Princeton Ps.

As for the generic type Held simply labeled “girls”: they look like the sort of women who could easily dance the night through. Their hair is the brightest blond, their eye shadow and lipstick thick as oil paint. Their clothing—and their trim, fabulous legs—make them very much like the woman who composed the music for Alma Mater: Kay Swift.

Kay Swift was a slightly airy—“comely,” according to one gossip columnist of the day—young woman accustomed to playing the piano before just about any audience. Seventeen years earlier, when she was the twenty-year-old Katharine Faulkner Swift, she had charmed the summer crowd with her playing at Fish Rock camp, Isaac Seligman’s place on Upper Saranac Lake in the Adirondacks. Margaret Lewisohn, Isaac’s daughter, had recently discovered her, and had imported her for the rest of the family to enjoy. Among the people most enchanted were Eddie Warburg’s aunt Nina and her daughter Bettina. They could hardly wait to tell Bettina’s brother James, then a young naval cadet flyer, about this ravishing young woman. With her brown laughing eyes, delicate nose, and fine jaw, the petite Katharine would be irresistible to him. She was quick, she was game, and she had musical talent besides.

Katharine had begun studying piano at age seven. Her father had been the music critic for the New York World. Following his death when she was a teenager, she had helped support her mother and brother by giving piano lessons in people’s homes. After winning a scholarship at the school that is now Juilliard and attending the New England Conservatory of Music, she had toured with a trio. When twenty-one-year-old Jimmy Warburg met her at a dance in New York, his mother’s and sister’s impressions were more than confirmed. The naval cadet and the musician decided to get married.

Eddie’s branch of the family didn’t think so highly of the match, however. This was the first time a Warburg had married a non-Jew. When Jimmy and Katharine announced their engagement, Jacob Schiff telegrammed, “I wish you joy to your happiness but cannot refrain from telling you that I am deeply disturbed by your action in marrying out of the faith in view of its probable effect upon my own progeny.”42 Since Schiff was a director of Western Union, it didn’t cost him anything to send his warning. Nor did it get him anywhere. In 1918, the war over, and Jimmy having become a banker, the pair was married.

In the 1920s Katharine and Jimmy Warburg lived the high life. They bought two adjacent houses on East Seventieth Street between Madison and Park avenues and knocked down the connecting walls to create rooms large enough for entertaining and raising three daughters. When the decorators came in to make changes, they simply moved family and staff around the corner to the Westbury Hotel so that work and play could run as usual. Hardship for Jimmy was to arrive at the bank exhausted after a long night playing poker with Franklin P. Adams, Alexander Woollcott, Marc Connelly, Herbert Bayard Swope, Harold Ross, and Raoul Fleischmann.

Katharine and Jimmy regularly attended musical evenings at the home of Walter Damrosch, where they grew to know George and Ira Gershwin, as well as Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart. Rodgers gave Katharine a job as rehearsal pianist for A Connecticut Yankee, after which she took an interest in popular music and decided she wanted to try her hand at composing songs. Jimmy wrote the lyrics. However, as a vice president of the International Acceptance Bank, he didn’t want to upset his depositors with his involvement in a profession they might consider undignified. So James Paul Warburg called himself Paul James, and Katharine Swift Warburg became Kay Swift.

Paul James and Kay Swift’s first big hit was a torch song called “Can’t We Be Friends?” that Libby Holman sang in the 1929 First Little Show. They decided to keep going. Donald Ogden Stewart had written the book for a full-length musical comedy for the slapstick comedian Joe Cook, and Swift and James were hired to do the music and lyrics. It was called Fine & Dandy. When the producers went broke just before the opening, Paul James simply took up his Jimmy Warburg side and came up with the necessary funds—aided by two of his best friends, Marshall Field and Averell Harriman, who had liked the new musical in rehearsal. Although the three investors never saw cash returns on the project, the show was a great success, running for more than 250 performances, and earning the accolade from the critic John Mason Brown that it was “one of the best musical comedies New York has seen in a blue moon.” Moreover, two Swift and James songs, “Fine & Dandy” and “Can This Be Love?”, entered the mainstream.

In Kay and Jimmy’s enormous living room, underneath the ornate, cherub-covered wooden ceiling and the rows of dark Dutch seventeenth-century portraits, there were two back-to-back concert grand pianos. Sometimes George Gershwin would play with Oscar Levant or Sigmund Romberg; sometimes he would play with Kay. Then, at Kay and Jimmy’s eighty-acre farm in Greenwich, Connecticut, he occupied the guest cottage for an entire summer. It was there that Gershwin, who had grown up in New York’s poorer neighborhoods, learned how to live upper-class American life. He rode horseback for the first time, and acquired the right clothes for the country. In addition, he worked with Kay on orchestration. Lacking her professional musical training, he benefited greatly from her technical expertise. Gershwin would try new rhythms and melodies; she would suggest the harmonic treatment. Working with her in this way, he composed Rhapsody No. 2 and Porgy and Bess. Often he dictated, and Kay wrote the music down; half of the original score of Porgy is in her hand.

Meanwhile, Jimmy Warburg was busy providing the scheme that led to the reopening of the nation’s banks, traveling to London as financial adviser to the American delegation at the London Economic Conference, writing a widely distributed book called The Money Muddle, and corresponding regularly with President Franklin Roosevelt. He and Kay drifted apart. Not only had Jimmy’s interests kept him away from home, but Kay’s involvement with Gershwin had gone beyond the confines of music. It was in the midst of the breakup of her marriage and the burgeoning of her new romance that Kay Swift was busily playing away in George Balanchine’s rehearsal hall.

Balanchine had first wanted Jerome Kern or George Gershwin to write the music for their new ballet. Eddie Warburg asked Gershwin, who said he was too busy but recommended Kay Swift. She seemed a fair choice; not only was she a gifted composer, but she was one of Eddie’s favorite family members. Where most Warburg wives spent most of their time planning menus, organizing the servants, and shopping for gifts, Kay was both gay and brilliant. It was she who had persuaded Felix that music was the right vocation for Gerry. Family members, including the man Kay was about to divorce, thought the arts were good hobbies but not professions; she prized them more highly. She had spark, and so did her music. When Alma Mater opened that December, she may have been second choice, but no one was disappointed in what she came up with. The audiences as well as most of the critics loved what they saw, and above all what they heard.

The Alma Mater premiere was the first public performance of “The American Ballet of New York,” a small troupe of graduates of the School of American Ballet. Balanchine had progressed well with his year-old school of seventy students. He was “enthusiastic about these lithe American girls and boys.” They were “better built than the youngsters of other nations and, while they may be slower to yield themselves to discipline, they were quicker to learn and eager beyond measure.”43 The sixteen girls and seven boys he had selected to show what the new enterprise was all about were mostly ages fourteen to sixteen.

Kirstein and Warburg opted to return to Hartford for this premiere. Not only had the Wadsworth Atheneum given them their start, but in the year since they arrived there with Balanchine, the new auditorium had allowed it to step up its activities beyond art exhibitions. Above all, there had been the Four Saints premiere, but the Atheneum had also become the home of the film screenings with which Warburg was involved from his office at the Museum of Modern Art. In a series in March and April, Jean Cocteau’s Le Sang d’un Poète, Sergei Eisenstein’s Thunder over Mexico, and René Clair’s A Nous La Liberté were presented. In October, another series had opened, with further work by Eisenstein and Clair as well as motion pictures by D. W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Fritz Lang, Josef Sternberg, and Walt Disney.