CHAPTER 12

Narnia: Exploring an Imaginative World

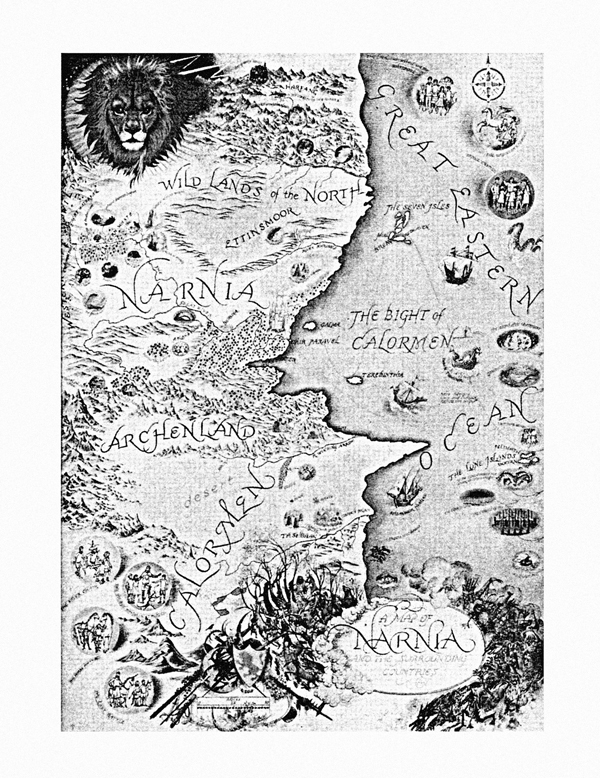

There are two main ways of exploring the Chronicles of Narnia. One—the easier, and by far the more natural—involves thinking of the individual novels as rooms in a house. We stroll around the rooms and their contents, enjoying working out how they are connected by corridors and doors. We are like tourists, wandering around a new town or country, taking in the sights and enjoying ourselves. And there is nothing wrong with this. Narnia, like any rich landscape, is worth exploring and getting to know. And, like most tourists, we might take a map of Narnia with us to help us make sense of what we see.

Yet there is a second way of reading the Narnian novels, which involves the imagination as the primary organ of investigation. This second way does not invalidate the first, but builds upon it and takes it further. Once more, we think of the Narnian novels as rooms in a house. Once more, we wander around the house, taking everything in. But we realise that the rooms in this house have windows. And when we look through them, we see things in a new way. We can see farther than before, as the landscape opens up in front of us. And what we come to see is not an accumulation of individual facts, but the bigger picture which underlies them. When seen in this way, our imaginative experience of Narnia enlarges our sense of reality. Living in our own world feels different afterwards.

12.1 “Map of Narnia,” drawn by Pauline Baynes.

Exploring Narnia is thus not just about encountering this strange and wonderful land; it is also about allowing it to shape the way we see our own land and our own lives. To use Lewis’s way of speaking, we can see Narnia as a spectacle, something to be studied in its own right, or we can see it—whether additionally or alternatively—as a pair of spectacles, something that makes it possible to see everything else in a new way, as things are brought into sharp focus. The story captivates us, making us see things its way—setting to one side the ordinary, and seeing the extraordinary instead.

So let us enter the world of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and explore both that strange place and the new ways of seeing things that it makes possible. And where better to begin than with its central character, the magnificent lion Aslan?

Aslan: The Heart’s Desire

How did Lewis develop the idea and image of a noble lion as his central character? Lewis himself seems to disclaim any privileged insight here. He once remarked, “I don’t know where the Lion came from or why He came. But once He was there He pulled the whole story together.” It is not, however, difficult to suggest possible explanations of how Aslan came “bounding into” Lewis’s imagination.593 Lewis’s close friend Charles Williams had written a novel titled The Place of the Lion (1931), which Lewis had read with interest, clearly appreciating how the image could be developed further.

The use of the image of a lion as a central character made perfect literary and theological sense to Lewis. A lion was already used widely in the Christian theological tradition as an image of Christ, following the New Testament’s reference to Christ as the “Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David” (Revelation 5:5). Furthermore, a lion is the traditional symbol associated with Lewis’s childhood church, St. Mark’s Anglican Church in Dundela, located on the outskirts of Belfast. The church’s rectory, which Lewis visited regularly as a child, had a door knocker in the form of a lion’s head. The use of the image of a lion is relatively easy to understand. But what about the lion’s name?

Lewis came across the specific name Aslan in the notes to Edward Lane’s translation of the Arabian Nights (1838). The name Aslan is particularly significant in Ottoman colonial history. Until the end of the First World War, Turkey was an imperial power, exercising considerable political and economic influence in many parts of the Middle East. Although Lewis links his discovery of the term with the Arabian Nights, it is entirely possible that he also came to know of it through Richard Davenport’s classic study of 1838, The Life of Ali Pasha, of Tepeleni, Vizier of Epirus: Surnamed Aslan, or the Lion. Davenport had earlier published an important life of Edmund Spenser (1822), which Lewis would have encountered while researching the poet. This Ottoman lineage explains how Lewis came to use the Turkish name “Aslan” for his great lion. “It is the Turkish for Lion. I pronounce it Ass-lan myself. And of course I meant the Lion of Judah.”594

The most characteristic feature of Lewis’s Aslan is that he evokes awe and wonder. Lewis develops this theme with relation to Aslan by emphasising the fact that he is wild—an awe-inspiring, magnificent creature, which has not been tamed through domestication, or had his claws pulled out to ensure he is powerless. As the Beaver whispers to the children, “He’s wild, you know. Not like a tame lion.”595

To understand the literary force of Lewis’s depiction of Aslan, we need to appreciate the importance of Lewis’s early reading of Rudolf Otto’s classic religious work The Idea of the Holy (1923). This work, which Lewis first read in 1936 and regularly identified as one of the most important books he had ever read,596 persuaded him of the importance of the “numinous”—a mysterious and awe-inspiring quality of certain things or beings, real or imagined, which Lewis described as seemingly “lit by a light from beyond the world.”597

Lewis devotes a substantial part of the opening chapter of The Problem of Pain to an analysis of Otto’s idea, and offers one specific literary illustration of its importance.598 Lewis notes the passage in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) in which Rat and Mole approach Pan:

“Rat!” [Mole] found breath to whisper, shaking, “Are you afraid?”

“Afraid?” murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. “Afraid? Of HIM? O never, never! And yet—and yet— O Mole, I am afraid!”599

This passage deserves to be read in full, as it had clearly influenced Lewis’s depiction of the impact of Aslan on the children and animals in Narnia. For example, Grahame speaks of Mole’s experiencing “an awe that smote and held him and, without seeing, he knew it could only mean that some august Presence was very, very near.”600

Otto’s account of numinous experience identifies two distinct themes: a mysterium tremendum, a sense of mystery which evokes fear and trembling; and mysterium fascinans, a mystery which fascinates and attracts. The numinous, for Otto, can thus terrify or energise, giving rise to a sense of either fear or delight, as suggested in Grahame’s dialogue. Other writers reframed the idea in terms of a “nostalgia for paradise,” which evokes an overwhelming sense of belonging elsewhere.

In describing the reaction of the children to the Beaver’s softly whispered confidence that “Aslan is on the move—perhaps has already landed,” Lewis offers one of the finest literary statements of the impact of the numinous:

And now a very curious thing happened. None of the children knew who Aslan was any more than you do; but the moment the Beaver had spoken these words everyone felt quite different. Perhaps it has sometimes happened to you in a dream that someone says something which you don’t understand but in the dream it feels as if it had some enormous meaning—either a terrifying one which turns the whole dream into a nightmare or else a lovely meaning too lovely to put into words, which makes the dream so beautiful that you remember it all your life and are always wishing you could get into that dream again. It was like that now. At the name of Aslan each one of the children felt something jump in its inside.601

Lewis then describes how this “numinous” reality impacts each of the four children in a quite different manner. For some, it evokes fear and trembling; for others, a sense of unutterable love and longing:

Edmund felt a sensation of mysterious horror. Peter felt suddenly brave and adventurous. Susan felt as if some delicious smell or some delightful strain of music had just floated by her. And Lucy got the feeling you have when you wake up in the morning and realize that it is the beginning of the holidays or the beginning of summer.602

Susan’s thoughts are clearly based on Lewis’s classic analysis of “longing,” found especially in his 1941 sermon “The Weight of Glory,” which speaks of this desire as “the scent of a flower we have not found” or “the echo of a tune we have not heard.”603

Lewis is here setting out, in a preliminary yet still powerful form, his core theme of Aslan as the heart’s desire. Aslan evokes wonder, awe, and an “unutterable love.” Even the name Aslan speaks to the depths of the soul. What would it be like to meet him? Lewis captures this complex sense of awe mingled with longing in the reaction of Peter to the Beaver’s declarations about this magnificent lion, who is “the King of the wood and the son of the great Emperor-beyond-the-Sea.” “‘I’m longing to see him,’ said Peter, ‘even if I do feel frightened.’”604

Lewis here transposes one of the central themes of works such as Mere Christianity into an imaginative mode. There is indeed a deep emptiness within human nature, a longing which none but God can satisfy. Using Aslan as God’s proxy, Lewis constructs a narrative of yearning and wistfulness, tinged with the hope of ultimate fulfilment. That this is no misguided strategy is strongly suggested by a powerful passage in the writings of Bertrand Russell (1872–1970), easily one of the most articulate and influential British atheist writers of the twentieth century:

The centre of me is always and eternally a terrible pain . . . a searching for something beyond what the world contains, something transfigured and infinite. The beatific vision—God. I do not find it, I do not think it is to be found—but the love of it is my life. . . . It is the actual spring of life within me.605

When, towards the end of The Voyage of the “Dawn Treader,” Lucy piteously declares that she cannot bear to be separated from Aslan, she echoes this theme of the longing of the human heart for God. If she and Edmund return to their own country, they fear they will never see Aslan again.

“It isn’t Narnia, you know,” sobbed Lucy. “It’s you. We shan’t meet you there. And how can we live, never meeting you?”

“But you shall meet me, dear one,” said Aslan.

“Are—are you there too, Sir?” said Edmund.

“I am,” said Aslan. “But there I have another name. You must learn to know me by that name. This was the very reason why you were brought to Narnia, that by knowing me here for a little, you may know me better there.”606

In using Aslan as a figure or type of Christ, Lewis stands within a long and continuing tradition of Christ figures in literature and film, such as Santiago, the “Old Man” in Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (1952).607 Such Christ figures are found in literature of all genres, including children’s books. The phenomenally successful Harry Potter series of novels incorporates a number of such themes. Gandalf is one of a number of Christ figures within Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, whose Christological role and associations are accentuated in Peter Jackson’s recent film version of the epic series.608

Lewis develops many of the classic Christological statements of the New Testament in the Chronicles of Narnia, generally focussing these on the person of Aslan. Yet perhaps his most intriguing reworking of a classic theological theme concerns his depiction of the death and resurrection of Aslan in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. So what does Lewis understand by atonement?

The Deeper Magic: Atonement in Narnia

One major theme in Christian theological reflection concerns how the death of Christ on the cross is to be interpreted, especially in relation to the salvation of humanity. These ways of interpreting the Cross, traditionally referred to as “theories of the Atonement,” have played a major role in Christian discussion and debate through the ages. Lewis positions his account of the death of Aslan at the hands of the White Witch within the context of this stream of thinking. But what ideas does Lewis himself develop?

Before considering this question, we need to appreciate that Lewis was not a professional theologian, and did not have any expert knowledge of the historical debates within the Christian tradition on this question. While some have tried to relate Lewis to, for example, the medieval debate between Anselm of Canterbury and Peter Abelard, this is not a particularly profitable approach. Lewis tends to know theological ideas through their literary embodiments. It is therefore not to professional theologians that we must turn to explore Lewis’s ideas on the Atonement, but to the English literary tradition—to works such as Piers Plowman, John Milton’s Paradise Lost, or the medieval mystery plays. It is here that we will find the approaches that Lewis weaves into his Narnian narrative.

Lewis’s first discussion of approaches to the Atonement is found in The Problem of Pain (1940). Lewis argues that any theory of the Atonement is secondary to the actuality of it. While these various theories may be useful to some, Lewis remarks, “they do no good to me, and I am not going to invent others.”609

Lewis returns to this theme in his broadcast talks of the 1940s. Lewis here remarks that, before he became a Christian, he held the view that Christians were obliged to take a specific position on the meaning of Christ’s death, and especially how it brought about salvation. One such theory was that human beings deserved to be punished for their sin, but “Christ volunteered to be punished instead, and so God let us off.” After his conversion, however, Lewis came to realise that theories about redemption are of secondary importance:

What I came to see later on was that neither this theory nor any other is Christianity. The central Christian belief is that Christ’s death has somehow put us right with God and given us a fresh start. Theories as to how it did this are another matter.610

In other words, “theories of the Atonement” are not the heart of Christianity; rather, they are attempts to explain how it works.

We see here Lewis’s characteristic resistance to the primacy of theory over theological or literary actuality. It is perfectly possible to “accept what Christ has done without knowing how it works.” Theories are always, Lewis holds, secondary to what they represent:

We are told that Christ was killed for us, that His death has washed out our sins, and that by dying He disabled death itself. That’s the formula. That’s Christianity. That’s what has to be believed. Any theories we build up as to how Christ’s death did all this are, in my view, quite secondary: mere plans or diagrams to be left alone if they don’t help us, and, even if they do help us, not to be confused with the thing itself.611

These reflections are in no way inconsistent with actually adopting such a theory; they merely set a theory in context, insisting that it is like a plan or diagram, which is “not to be confused with the thing itself.”

One of the most shocking and disturbing scenes in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is the death of Aslan. Where the New Testament speaks of the death of Christ as redeeming humanity, Lewis presents Aslan’s death as initially benefitting one person, and one person only—Edmund. The easily misled boy falls into the hands of the White Witch. Alarmed that the presence of humans in Narnia is a portent of the end of her reign, she attempts to neutralise them, using Edmund as her unwitting agent. In his attempts to secure her goodwill (and more Turkish Delight), Edmund deceives his siblings. And that act of deception proves to be a theological turning point.

The White Witch demands a meeting with Aslan, at which she declares that Edmund, by committing such an act of betrayal, has come under her authority. She has a right to his life, and she intends to exercise that right. The Deep Magic built into Narnia at its beginning by the Emperor-beyond-the-Sea laid down “that every traitor belongs to me as my lawful prey and that for every treachery I have a right to a kill.”612 Edmund is hers. His life is forfeit. And she demands his blood.

Then a secret deal is done, of which the children know nothing. Aslan agrees to act as a substitute for Edmund. He will die, so that Edmund may live. Unaware of what is about to happen, Lucy and Susan follow Aslan as he walks towards the hill of the Stone Table, to be bound and to offer to die himself at the hands of the White Witch. This scene is as moving as it is horrific, and parallels at some points—but not at others—the New Testament accounts of Christ’s final hours in the garden of Gethsemane and his subsequent crucifixion. Aslan is put to death, surrounded by a baying mob, who mock him in his final agony.

One of the most moving scenes in the entire Narnia series describes how Susan and Lucy approach the dead lion, kneeling before him as they “kissed his cold face and stroked his beautiful fur,” crying “till they could cry no more.”613 Lewis here shows himself at his imaginative best, reworking the themes of the images and texts of medieval piety—such as the classic Pietà (the image of the dead Christ being held by his mother, Mary), and the text Stabat Mater Dolorosa (describing the pain and sorrow of Mary at Calvary, as she weeps at the scene of Christ’s death).

Then everything is unexpectedly transformed. Aslan comes back to life. The witnesses to this dramatic moment are Lucy and Susan alone, paralleling the New Testament’s insistence that the first witnesses to the resurrection of Christ were three women. They are astonished and delighted, flinging themselves upon Aslan and covering him with kisses. What has happened?

“But what does it all mean?” asked Susan when they were somewhat calmer.

“It means,” said Aslan, “that though the Witch knew the Deep Magic, there is a magic deeper still which she did not know. Her knowledge goes back only to the dawn of time. But if she could have looked a little further back, into the stillness and the darkness before Time dawned, she would have read there a different incantation. She would have known that when a willing victim who had committed no treachery was killed in a traitor’s stead, the Table would crack and Death itself would start working backward.”614

Aslan thus lives again, and Edmund is liberated from any legitimate claim on the White Witch’s part.

And there is still more to come. The courtyard of the White Witch’s castle is filled with petrified Narnians, turned into stone by the Witch. Following his resurrection, Aslan breaks down the castle gates, romps into the courtyard, breathes upon the statues, and restores them to life. Finally, he leads the liberated army through the shattered gates of the once-great fortress to fight for the freedom of Narnia. It is a dramatic and highly satisfying end to the narrative.

But where do these ideas come from? They are all derived from the writings of the Middle Ages—not works of academic theology, which generally were critical of such highly visual and dramatic approaches, but the popular religious literature of the age, which took pleasure in a powerful narrative of Satan’s being outmanoeuvred and outwitted by Christ.615 According to these popular atonement theories, Satan had rightful possession over sinful human beings. God was unable to wrest humanity from Satan’s grasp by any legitimate means. Yet what if Satan were to overstep his legitimate authority, and claim the life of a sinless person—such as Jesus Christ, who, as God incarnate, was devoid of sin?

The great mystery plays of the Middle Ages—such as the cycle performed at York in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries—dramatised the way in which a wily and canny God tricked Satan into overstepping his rights, and thus forfeiting them all. An arrogant Satan received his comeuppance, to howls of approval from the assembled townspeople. A central theme of this great popular approach to atonement was the “Harrowing of Hell”—a dramatic depiction of the risen Christ battering the gates of hell, and setting free all who were imprisoned within its realm.616 All of humanity were thus liberated by the death and resurrection of Christ. In Narnia, Edmund is the first to be saved by Aslan; the remainder are restored to life later, as Aslan breathes on the stone statues in the Witch’s castle.

Lewis’s narrative in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe contains all the main themes of this medieval atonement drama: Satan having rights over sinful humanity; God outwitting Satan because of the sinlessness of Christ; and the breaking down of the gates of Hell, leading to the liberation of its prisoners. The imagery is derived from the great medieval popular religious writings which Lewis so admired and enjoyed.

So what are we to make of this approach to atonement? Most theologians regard Lewis’s narrative depiction of atonement with mild amusement, seeing it as muddled and confused. But this is to misunderstand both the nature of Lewis’s sources and his intentions. The great medieval mystery plays aimed to make the theological abstractions of atonement accessible, interesting, and above all entertaining. Lewis has brought his own distinct approach to this undertaking, but its historical roots and imaginative appeal are quite clear.

The Seven Planets: Medieval Symbolism in Narnia

Each of the seven Chronicles of Narnia has its own distinct literary identity—a “feel” or “atmosphere” that gives each novel its own place in the septet. So how did Lewis maintain the unity of the narrative as a whole, while giving each novel its own characteristic individuality?

It is a classic issue in literary history. Lewis would have known that Richard Wagner (1813–1883) managed to maintain the thematic unity of his massive operatic cycle The Ring of the Nibelungs by using musical motifs that recurred throughout the four operas of the drama, acting as threads that hold its fabric together. So what did Lewis do?

Lewis’s reading of the Elizabethan Renaissance poet Edmund Spenser (ca. 1552–1599) led him to discover and appreciate the importance of a unifying device that allowed Spenser to bind together complex and diverse plots, characters, and adventures. Spenser’s Faerie Queene (1590–1596) is a vast work, which Lewis realised maintained its unity and cohesion by a superb literary device—one that he himself would use in the Chronicles of Narnia.

What is this unifying device? Quite simply, according to Lewis, it is Faerie Land, which provides a place that is “so exceeding spatious and wide” that it can be packed full of adventures without loss of unity. “‘Faerie Land’ itself provides the unity—a unity not of plot, but of milieu.”617 A central narrative holds each of Spenser’s seven books together, while at the same time providing space for “a loose fringe of stories,” which are subordinate to its central structure.

The land of Narnia plays a role in Lewis’s narrative which parallels that of Faerie Land for Spenser’s. Lewis realised how a complex narrative can easily degenerate into a bundle of unrelated stories. Somehow, they had to be held together. It is perhaps no accident that there are seven books in the Chronicles of Narnia, paralleling the structure—though not the substance—of Spenser’s Faerie Queene. The land of Narnia allows Lewis to give an overall thematic unity to the septet. But how did he give each novel its own distinct literary aura? How did he ensure that each constituent part of the Chronicles of Narnia had a coherent identity in its own right?

Lewis’s critics and interpreters have devoted much attention to decoding the significance of the seven Narnia novels. Of the many debates, the most interesting is this: why are there seven novels? Speculation has been intense. We have already noted that Spenser’s Faerie Queen has seven books, perhaps suggesting that Lewis saw his own work as paralleling this Elizabethan classic. And maybe it does—but if so, only in some very specific respects, such as the unifying role of Faerie Land for a complex narrative. Or perhaps it is an allusion to the seven sacraments? Possibly—but Lewis was an Anglican, not a Catholic, and recognised only two sacraments. Or perhaps there is an allusion to the seven deadly sins? Possibly—but any attempt to assign the novels to individual sins, such as pride or lust, seems hopelessly forced and unnatural. For example, which of the Narnia Chronicles majors on gluttony? Amidst the wreckage of these implausible suggestions, an alternative has recently emerged—that Lewis was shaped by what the great English seventeenth-century poet John Donne called “the Heptarchy, the seven kingdoms of the seven planets.” And amazingly, this one seems to work.

The idea was first put forward by Oxford Lewis scholar Michael Ward in 2008.618 Noting the importance that Lewis assigns to the seven planets in his studies of medieval literature, Ward suggests that the Narnia novels reflect and embody the thematic characteristics associated in the “discarded” medieval worldview with the seven planets. In the pre-Copernican worldview, which dominated the Middle Ages, Earth was understood to be stationary; the seven “planets” revolved around Earth. These medieval planets were the Sun, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Lewis does not include Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto, since these were only discovered in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, respectively.

So what is Lewis doing? Ward is not suggesting that Lewis reverts to a pre-Copernican cosmology, nor that he endorses the arcane world of astrology. His point is much more subtle, and has enormous imaginative potential. For Ward, Lewis regarded the seven planets as being part of a poetically rich and imaginatively satisfying symbolic system. Lewis therefore took the imaginative and emotive characteristics which the Middle Ages associated with each of the seven planets, and attached these to each of the seven novels as follows:

- The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe: Jupiter

- Prince Caspian: Mars

- The Voyage of the “Dawn Treader”: the Sun

- The Silver Chair: the Moon

- The Horse and His Boy: Mercury

- The Magician’s Nephew: Venus

- The Last Battle: Saturn

For example, Ward argues that Prince Caspian shows the thematic influence of Mars.619 This is seen primarily at two levels. First, Mars was the ancient god of war (Mars Gradivus). This immediately connects to the dominance of military language, imagery, and issues in this novel. The four Pevensie children arrive in Narnia “in the middle of a war”—“the Great War of Deliverance,” as it is referred to later in the series, or the “Civil War” in Lewis’s own “Outline of Narnian History.”

Yet in an earlier phase of the classical tradition, Mars was also a vegetation deity (known as Mars Silvanus), associated with burgeoning trees, woods, and forests. The northern spring month of March, during which vegetation comes back to life after winter, was named after this deity. Many readers of Prince Caspian have noted its emphasis on vegetation and trees. This otherwise puzzling association, Ward argues, is easily accommodated within the range of ideas associated with Mars by the medieval tradition.

If Ward is right, Lewis has crafted each novel in the light of the atmosphere associated with one of the planets in the medieval tradition. This does not necessarily mean that this symbolism determines the plot of each novel, or the overall series; it does, however, help us understand something of the thematic identity and stylistic tone of each individual novel.

Ward’s analysis is generally agreed to have opened up important new ways of thinking about the Narnia series, although further discussion and evaluation will probably lead to modification of some of its details. There is clearly more to Lewis’s imaginative genius than his earlier interpreters appreciated. If Ward is right, Lewis has used themes drawn from his own specialist field of medieval and Renaissance literature to ensure the coherency of the Chronicles of Narnia as a whole, while at the same time giving each book its own distinct identity.

The Shadowlands: Reworking Plato’s Cave

“It’s all in Plato, all in Plato: bless me, what do they teach them at these schools!”620 Lewis places these words in the mouth of Lord Digory in The Last Battle, as he tries to explain that the “old Narnia,” which had a historical beginning and end, was really “only a shadow or a copy of the real Narnia which has always been here and always will be here.”621 A central theme of many of Lewis’s writings is that we live in a world that is a “bright shadow” of something greater and better. The present world is a “copy” or “shadow” of the real world. This idea is found both in the New Testament in different forms—especially the letter to the Hebrews—and in the great literary and philosophical tradition which takes its inspiration from the classical Greek philosopher Plato (ca. 424–348 BC).

We see this theme developed in the climax of the epic of Narnia, The Last Battle. Lewis here invites us to imagine a room with a window that looks out onto a beautiful valley or a vast seascape. On a wall opposite this window is a mirror. Imagine looking out of the window, and then turning and seeing the same thing reflected in the mirror. What, Lewis asks, is the relationship between these two different ways of seeing things?

The sea in the mirror, or the valley in the mirror, were in one sense just the same as the real ones: yet at the same time they were somehow different—deeper, more wonderful, more like places in a story: in a story you have never heard but very much want to know. The difference between the old Narnia and the new Narnia was like that. The new one was a deeper country: every rock and flower and blade of grass looked as if it meant more.622

We live in the shadowlands, in which we hear echoes of the music of heaven, catch sight of its bright colours, and discern its soft fragrance in the air we breathe. But it is not the real thing; it is a signpost, too easily mistaken for the real thing.

The image of a mirror helps Lewis explain the difference between the old Narnia (which must pass away) and the new Narnia. Yet perhaps the most important Platonic image used by Lewis is found in The Silver Chair—Plato’s Cave. In his dialogue The Republic, Plato asks his readers to imagine a dark cave, in which a group of people have lived since their birth. They have been trapped there for their entire lives, and know about no other world. At one end of the cave, a fire burns brightly, providing them with both warmth and light. As the flames rise, they cast shadows on the walls of the cave. The people watch these shadows projected on the wall in front of them, wondering what they represent. For those living in the cave, this world of flickering shadows is all that they know. Their grasp of reality is limited to what they see and experience in this dark prison. If there is a world beyond the cave, it is something which they do not know and cannot imagine. They know only about the shadows.

Lewis explores this idea through his distinction between the “Overworld” and the “Underworld” in The Silver Chair. The inhabitants of the Underworld—like the people in Plato’s Cave—believe that there is no other reality. When the Narnian prince speaks of an Overworld, lit up by a sun, the Witch argues that he is simply making it up, copying realities in the Underworld. The prince then tries to use an analogy to help his audience understand his point:

“You see that lamp. It is round and yellow and gives light to the whole room; and hangeth moreover from the roof. Now that thing which we call the sun is like the lamp, only far greater and brighter. It giveth light to the whole Overworld and hangeth in the sky.”

“Hangeth from what, my Lord?” asked the Witch; and then, while they were all still thinking how to answer her, she added, with another of her soft, silver laughs, “You see? When you try to think out clearly what this sun must be, you cannot tell me. You can only tell me it is like the lamp. Your sun is a dream; and there is nothing in that dream that was not copied from the lamp. The lamp is the real thing; the sun is but a tale, a children’s story.”623

Then Jill intervenes: what about Aslan? He’s a lion! The Witch, slightly less confidently now, asks Jill to tell her about lions. What are they like? Well, they’re like a big cat! The Witch laughs. A lion is just an imagined cat, bigger and better than the real thing. “You can put nothing into your make-believe without copying it from the real world, this world of mine, which is the only world.”624

Most readers of this section of the book will smile at this point, realising that a seemingly sophisticated philosophical argument is clearly invalidated by the context within which Lewis sets it. Yet Lewis has borrowed this from Plato—while using Anselm of Canterbury and René Descartes as intermediaries—thus allowing classical wisdom to make an essentially Christian point.

Lewis is clearly aware that Plato has been viewed through a series of interpretative lenses—those of Plotinus, Augustine, and the Renaissance being particularly familiar to him. Readers of Lewis’s Allegory of Love, The Discarded Image, English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, and Spenser’s Images of Life will be aware that Lewis frequently highlights how extensively Plato and later Neoplatonists influenced Christian literary writers of both the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Lewis’s achievement is to work Platonic themes and images into children’s literature in such a natural way that few, if any, of its young readers are aware of Narnia’s implicit philosophical tutorials, or its grounding in an earlier world of thought. It is all part of Lewis’s tactic of expanding minds by exposing them to such ideas in a highly accessible and imaginative form.

The Problem of the Past in Narnia

Anyone reading The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe for the first time is likely to be impressed by its medieval imagery—its royal courts, castles, and chivalrous knights. It bears little relation to the 1939 world from which the four children come—or to that of subsequent readers. So is Lewis encouraging his readers to retreat into the past to escape the realities of modern life?

There are unquestionably points at which Lewis believes the past to be preferable to the present. For example, Lewis’s battle scenes tend to emphasise the importance of boldness and bravery in personal combat. Battle is about hand-to-hand and face-to-face encounters between noble and dignified foes, in which killing is a regrettable but necessary part of securing victory. This is far removed from the warfare Lewis himself experienced in the fields around Arras in late 1917 and early 1918, where an impersonal technology hurled explosive death from a distance, often destroying friend as well as foe. There was nothing brave or bold about modern artillery or machine guns. You hardly ever got to see who killed you.

Yet Lewis is not expecting his readers to retreat to a nostalgic and imaginary re-creation of the Middle Ages; still less is he urging us to re-create its ideas and values. Rather, Lewis is giving us a way of thinking by which we can judge our own ideas, and come to realise that they are not necessarily “right” on account of being more recent. In the Narnia series, Lewis presents a way of thinking and living in which everything fits together into a single, complex, harmonious model of the universe—the “discarded image” which Lewis explores in so many of his later scholarly writings. In doing this, he invites us to reconsider our present ways of thinking in order to reflect on whether we have lost something on our journey, and might be able to recover it.

Yet there is a problem here. Today’s readers of the Chronicles of Narnia have to make a double leap of the imagination—not simply to imagine Narnia, but to imagine the world from which its four original visitors come, shaped by the social presuppositions, hopes, and fears of Britain in the aftermath of the Second World War. How many of today’s readers of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe—smiling at the lure of Turkish Delight for Edmund (while wondering what this mysterious substance might be)—realise that the rationing of sweets did not end in Britain until February 1953, four years after the book was written? The modest sumptuousness of Narnian feasts contrasts sharply with the austerity of postwar Britain, in which even basic foodstuffs were in short supply. To appreciate the full impact of the series on its original readers, we must try to enter into a bygone world, as well as an imagined one.

At several points, this becomes a problem for today’s readers. The most obvious of these difficulties concerns the children in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, who are white, middle-class English boys and girls with somewhat stilted and “golly gosh” turns of phrase. Lewis’s characters probably sounded a little stilted and unnatural even to his readers in the early 1950s. Many readers now need a cultural dictionary to make sense of Peter’s schoolboy jargon, such as “Old chap!” “By Jove!” and “Great Scott!”

More problematically, some of the social attitudes of middle-class England during the 1930s and 1940s—and occasionally those of Lewis’s own childhood during the 1910s—are deeply embedded within the Narnia novels. The most obvious of these concerns women. It is clearly unfair to criticise Lewis for failing to anticipate twenty-first-century Western cultural attitudes on this matter. Nevertheless, some have argued that Lewis allocates subordinate roles to his female characters throughout the Chronicles of Narnia, and wish he had broken free of the traditional gender roles of that age.

The case of Susan is often singled out for special comment. While playing a prominent role in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, she is conspicuously absent from the final volume in the series, The Last Battle. Philip Pullman, Lewis’s most outspoken recent critic, declares that Susan “was sent to hell because she was getting interested in clothes and boys.”625 Pullman’s intense hostility towards Lewis seems to subvert any serious attempt at objective evidential analysis on his part. As all readers of the Narnia series know, at no point does Lewis suggest that Susan is “sent to hell,” let alone because of an interest in “boys.”

Yet Susan illustrates a concern that some recent commentators have expressed about the stories of Narnia—namely, that they tend to privilege male agents. Might Narnia have been different if Lewis had met a Ruth Pitter or a Joy Davidman in the 1930s?

It is, however, important to be fair to Lewis here. Despite the social predominance of male role models in his cultural context, the gender roles in the Chronicles of Narnia tend to be evenly balanced. Indeed, if there is a lead human character in the Chronicles of Narnia, this is played by a female. Lucy is the protagonist in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. She is the first to gain access to Narnia, and is the human who becomes closest to Aslan. She plays the lead role in Prince Caspian, and speaks the final words of human dialogue at the end of The Last Battle. Lewis was ahead of British views on gender roles during the 1940s, when the Chronicles of Narnia were conceived; he lags behind now—but not by as much as his critics suggest.

But we now must leave the imagined realm of Narnia, and return to the real world of Oxford in the early 1950s. As we noted earlier, Lewis was becoming increasingly beleaguered and isolated. But what could he do about it?