CHAPTER 14

1960–1963

Bereavement, Illness, and Death: The Final Years

Joy Davidman died of cancer at the age of forty-five at the Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, on 13 July 1960, with Lewis at her bedside. At her request, her funeral took place at Oxford’s crematorium on 18 July. The service was led by Austin Farrer, one of the relatively few among Lewis’s circle who had come to like Davidman. Her memorial plaque remains there, and is to this day one of the crematorium’s best-known features.

Lewis was devastated. Not only had he lost his wife, whom he had nursed through her illness, and had come to love; he had also lost a personal Muse, a source of literary encouragement and inspiration. Davidman had been a significant influence on three of his late books—Till We Have Faces, Reflections on the Psalms, and The Four Loves. Now Davidman would be instrumental for one of Lewis’s darkest and most revealing works. Her death unleashed a stream of thoughts which Lewis could not initially control. In the end, he committed them to writing as a way of coping with them. The result was one of his most distressing and disturbing books: A Grief Observed.

A Grief Observed (1961): The Testing of Faith

In the months following Davidman’s death, Lewis went through a process of grieving which was harrowing in its emotional intensity, and unrelenting in its intellectual questioning and probing. What Lewis once referred to as his “treaty with reality” was overwhelmed with a tidal wave of raw emotional turmoil. “Reality smashe[d] my dream to bits.”702 The dam was breached. Invading troops crossed the frontier, securing a temporary occupation of what was meant to be safe territory. “No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear.”703 Like a tempest, unanswered and unanswerable questions surged against Lewis’s faith, forcing him against a wall of doubt and uncertainty.

Faced with these unsettling and disquieting challenges, Lewis coped using the method he had recommended to his confidant Arthur Greeves in 1916: “Whenever you are fed up with life, start writing: ink is the great cure for all human ills, as I have found out long ago.”704 In the days following Davidman’s death in July 1960, Lewis began to write down his thoughts, not troubling to conceal his own doubts and spiritual agony. A Grief Observed is an uncensored and unrestrained account of Lewis’s feelings. He found liberty and release in being able to write what he actually thought, rather than what his friends and admirers believed he ought to think.

Lewis discussed the manuscript with his close friend Roger Lancelyn Green in September 1960. What should he do with it? Eventually, they agreed that it ought to be published. Lewis, anxious not to cause his friends any embarrassment, decided to conceal his authorship of A Grief Observed. He did this in four ways:

- By using the leading literary publisher Faber & Faber instead of Geoffrey Bles, his long-standing London publisher. Lewis handed the text over to his literary agent, Spencer Curtis Brown, who submitted it to Faber & Faber, without giving any indication that Lewis had any connection with the work. This was designed to lay a false trail for literary detectives.

- By using a pseudonym for the author—“N. W. Clerk.” Lewis originally suggested the Latin pseudonym Dimidius (“cut in half”). T. S. Eliot, a director of Faber & Faber, who immediately guessed the true identity of the obviously erudite author on reading the text submitted by Curtis Brown, suggested that a more “plausible English pseudonym” would “hold off enquirers better than Dimidius.”705 Lewis had already used several pen names to conceal the authorship of his poems. The name he finally chose is derived from the abbreviation of Nat Whilk (an Anglo-Saxon phrase best translated as “I don’t know who”) and “Clerk” (someone who is able to read and write). Lewis had earlier used the Latinised form of this name—Natwilcius—to refer to a scholarly authority in his 1943 novel Perelandra.

- By using a pseudonym for the central figure of the narrative—“H.,” presumably an abbreviation of “Helen,” a forename that Davidman rarely used yet which appeared on legal documents concerning her marriage and naturalisation as a British citizen, and her death certificate, which refers to her as “Helen Joy Lewis,” “wife of Clive Staples Lewis.”

- By altering his style. A Grief Observed is deliberately written using a format and writing style which none of his regular readers would naturally associate with Lewis. By incorporating these “small stylistic disguisements all the way along,” Lewis hoped to throw his readers off the scent.706 Few early readers of the work appear to have made the connection with Lewis.

Even to those who recognised at least some telltale signs of Lewis’s style in the work (such as its clarity), A Grief Observed seemed quite unlike anything else he had written. The book is about feelings, and their deeper significance in subjecting any “treaty with reality” to the severe testing which alone can prove whether it is capable of bearing the weight that is placed upon it. Lewis was famously uncomfortable about discussing his private emotions and feelings, having even apologised to his readers for the “suffocatingly subjective” approach he adopted at certain points in his earlier work Surprised by Joy.707

A Grief Observed engages emotions with a passion and intensity unlike anything else in Lewis’s body of works, past or future. Lewis’s earlier discussion of suffering in The Problem of Pain (1940) tends to treat it as something that can be approached objectively and dispassionately. The existence of pain is presented as an intellectual puzzle which Christian theology is able to frame satisfactorily, if not entirely resolve. Lewis was quite clear about his intentions in writing this earlier work: “The only purpose of the book is to solve the intellectual problem raised by suffering.”708 Lewis may have faced all the intellectual questions raised by suffering and death before. Yet nothing seems to have prepared him for the emotional firestorm that Davidman’s death precipitated.

Suffering can only be little more than a logical riddle for those who encounter it from a safe distance. When it is experienced directly and immediately, firsthand—as when Lewis lost his mother, and again at the devastating death of Davidman—it is like an emotional battering ram, crashing into the gates of the castle of faith. To its critics, The Problem of Pain amounts to an evasion of the reality of evil and suffering as experienced realities; instead, they are reduced to abstract ideas, which demand to be fitted into the jigsaw puzzle of faith. To read A Grief Observed is to realise how a rational faith can fall to pieces when it is confronted with suffering as a personal reality, rather than as a mild theoretical disturbance.

Lewis seems to have realised that his earlier approach had engaged with the surface of human life, not its depths:

Where is God? . . . Go to Him when your need is desperate, when all other help is vain, and what do you find? A door slammed in your face, and a sound of bolting and double bolting on the inside. After that, silence.709

In June 1951, Lewis wrote to Sister Penelope to ask for her prayers. Everything was too easy for him. “I am (like the pilgrim in Bunyan) travelling across ‘a plain called Ease.’” Might a change in his circumstances, he wondered, lead him to a deeper appreciation of his faith? Might a religious idea that he now understood only partly, if at all, suddenly take on new significance, becoming a new reality? “I now feel that one must never say one believes or understands anything: any morning a doctrine I thought I already possessed may blossom into this new reality.”710 It is difficult to read this without reflecting on how the somewhat superficial engagement with suffering in The Problem of Pain would “blossom” into the more mature, engaged, and above all wise account found in A Grief Observed.

Lewis’s powerful, frank, and honest account of his own experience in A Grief Observed is to be valued as an authentic and moving account of the impact of bereavement. It is little wonder that the work has secured such a wide readership, given its accurate description of the emotional turmoil that results from a loved one’s death. Indeed, some even recommended it to Lewis as an excellent account of the process of grieving, quite unaware of its true origins. Yet the work is significant at another level, in exposing the vulnerability and fragility of a purely rational faith. While Lewis undoubtedly recovered his faith after his wife’s death, A Grief Observed suggests that this faith was some distance removed from the cool, logical approach to faith that he once set out in The Problem of Pain.

Some have mistakenly concluded that A Grief Observed is a tacit acknowledgement of the explanatory failure of Christianity, and that Lewis emerged from this process of grieving as an agnostic. This is a hasty and superficial conclusion, and shows a lack of familiarity with the text itself, or with Lewis’s subsequent writings. It must be remembered that A Grief Observed describes what Lewis regards as a process of testing—not a testing of God, but a testing of Lewis. “God has not been trying an experiment on my faith or love in order to find out their quality. He knew it already. It was I who didn’t.”711

Those wishing to present Lewis as having become an agnostic at this time must selectively freeze that narrative, presenting one of its frames or phases as its final outcome. Lewis makes it clear that, in his distress, he sets out to explore every intellectual option open to him. No stone was to remain unturned, no path unexplored. Maybe there is no God. Maybe there is a God, but he turns out to be a sadistic tyrant. Maybe faith is just a dream. Like the psalmist, Lewis plumbs the depths of despair, relentlessly and thoroughly, determined to wrest the hidden meaning from their darkness. Finally, Lewis begins to recover a sense of spiritual balance, recalibrating his theology in light of the shattering events of the previous weeks.

A letter Lewis wrote a few weeks before his death both captures the argumentative flow of A Grief Observed and accurately summarises its outcome. Lewis had maintained a correspondence since the early 1950s with Sister Madeleva Wolff (1887–1964), a distinguished medieval literary scholar and poet who had recently retired as president of Saint Mary’s College at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana. Lewis speaks of expressing his grief “from day to day in all its rawness and sinful reactions and follies.” He warns her that, though A Grief Observed “ends with faith,” it nevertheless “raises all the blackest doubts en route.”712

It is all too easy—especially for those predisposed towards depicting Lewis as having become an agnostic, or who lack the time to read him properly—to fix on these “sinful reactions and follies” as if they represent the final outcome of Lewis’s no-holds-barred exploration of the entire gamut of theistic possibilities in response to his crisis of grief. Yet Lewis’s judgement on his own writing is precisely the conclusion that will be reached by anyone who reads the work in its entirety.

It is difficult, and possibly quite improper, to seize on a single moment, a solitary statement, that represents a turning point in Lewis’s grief-stricken meditations. Yet there seems to be a clear tipping point in Lewis’s thinking, which centres around his desire to be able to suffer instead of his wife: “If only I could bear it, or the worst of it, of any of it, instead of her.”713 Lewis’s line of thought is that this is the mark of the true lover—a willingness to take on pain and suffering, in order that the beloved might be spared its worst.

Lewis then makes the obvious, and critical, Christological connection: that this is what Jesus did at the Cross. Is it allowed, he “babbles,” to take on suffering on behalf of someone else, so that they are spared at least something of its pain and sense of dereliction? The answer lies in the crucified Christ:

It was allowed to One, we are told, and I find I can now believe again, that He has done vicariously whatever can be so done. He replies to our babble, “You cannot and you dare not. I could and dared.”714

There are two interconnected, yet distinct, points being made here. First, Lewis is coming to a realisation that, great though his love for his wife may have been, it had its limits. Self-love will remain present in his soul, tempering his love for anyone else and limiting the extent to which he is prepared to suffer for that person. Second, Lewis is moving towards, not so much a recognition of the self-emptying of God (that theological idea is readily found elsewhere in his writings), but a realisation of its existential significance for the problem of human suffering. God could bear suffering. And God did bear suffering. And that, in turn, allows us to bear the ambiguity and risks of faith, knowing that its outcome is secured. A Grief Observed is a narrative of the testing and maturing of faith, not simply its recovery—and certainly not its loss.

So why did Lewis react so severely to Davidman’s death? There are clearly a number of factors involved. However questionably the relationship had been initiated, Davidman had become Lewis’s lover and intellectual soul mate, who helped him retain his passion and motivation for writing. She played—or, more accurately, was allowed to play—a role unique among Lewis’s female circle. Her loss was deeply felt.

In the end the storm was stilled, and the waves ceased to crash against Lewis’s house of faith. The assault had been extreme, and the testing severe. Yet its outcome was a faith which, like gold, had passed through the refiner’s fire.

Lewis’s Failing Health, 1961–1962

Lewis’s faith might have survived, perhaps even becoming more robust. But the same could not be said of his health. In June 1961, Lewis spent two days in Oxford with his childhood friend Arthur Greeves. It was, he later declared, “one of the happiest times.” Yet Lewis’s letter to Greeves thanking him for visiting him had a darker aspect. Lewis disclosed he would soon have to enter the hospital for an operation to deal with an enlarged prostate gland.715 It is unlikely that Greeves would have been totally surprised by this news. Lewis, he had noted during his visit, “was looking very ill.” Something was clearly wrong with him.

The operation was scheduled to take place on 2 July in the Acland Nursing Home, a private medical facility outside the National Health Service, close to the centre of Oxford. Yet it soon became clear to Lewis’s medical team that any operation was out of the question. His kidneys and heart were both failing him. His condition was inoperable. It could only be managed; it could not be cured. By the end of the summer, Lewis was so ill that he was unable to return to Cambridge to teach in the Michaelmas Term of 1961.

Realising that he might not live much longer, Lewis drew up his will. This document, dated 2 November 1961, appointed Owen Barfield and Cecil Harwood as his executors and trustees.716 Lewis bequeathed his books and manuscripts to his brother, along with any income arising from Lewis’s publications during the period of his lifetime. After Warnie’s death, Lewis’s residuary estate was to pass to his two stepsons. The will made no provision for a literary executor. Warnie would receive income from Lewis’s publications, but would have no legal rights over them.

Lewis also stipulated that four further individuals were to receive £100, if there were sufficient funds in Lewis’s bank account at the time of his death: Maureen Blake and his three godchildren, Laurence Harwood, Lucy Barfield, and Sarah Neylan.717 Shortly afterwards, Lewis seems to have realised that he had failed to give any recognition to those who had cared for him at The Kilns. In a codicil of 10 December 1961, Lewis added two further names to this list: his gardener and handyman Fred Paxford, who was to receive £100, and his housekeeper Molly Miller, who was to receive £50.

14.1 The Acland Nursing Home, 25 Banbury Road, Oxford, in 1900. The nursing home, founded in 1882, was named after Sarah Acland, wife of Sir Henry Acland, formerly Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford University. It moved to its Banbury Road site in 1897.

These seem paltry sums, given that, after probate on 1 April 1964, Lewis’s estate was valued at £55,869, with a death duty payable of £12,828. Yet Lewis had little idea of his personal worth, and was now constantly worried about large demands from the Inland Revenue, which might bring him close to bankruptcy. His will also reveals anxiety over what might happen if the death duty were to exceed his realisable assets.

Lewis had hoped to be able to return to his normal teaching responsibilities at Magdalene College the next term, in January 1962. Yet as the months passed, Lewis realised that he was simply not well enough to allow this to happen. He wrote to a student he was meant to be supervising to apologise for his enforced absence in the spring of 1962, and to explain the problem:

They can’t operate on my prostate till they’ve got my heart and kidneys right, and it begins to look as if they can’t get my heart & kidneys right till they operate on my prostate. So we’re in what an examinee, by a happy slip of the pen, called “a viscous circle.”718

Lewis was finally able to go back to Cambridge on 24 April 1962 and resume his teaching, giving biweekly lectures on Spenser’s Faerie Queene.719 Yet he had not been healed; his condition had merely been stabilised through a careful diet and exercise regimen. Apologizing to Tolkien for being unable to attend a celebratory dinner at Merton College the following month to mark the publication of a collection of essays dedicated to him, Lewis explained that he now had to “wear a catheter, live on a low protein diet, and go early to bed.”720

The catheter in question was an amateurish contraption involving corks and pieces of rubber tubing, which was notoriously prone to leaks. It had been devised by Lewis’s friend Dr. Robert Havard, whose failure to diagnose Davidman’s cancer early enough to allow intervention ought to have raised some questions in Lewis’s mind about his professional competence. Lewis grumbled about Havard’s shortcomings in a letter of 1960, noting that he “could and should have diagnosed Joy’s trouble when she went to him about the symptoms years ago before we were married.”721 Yet despite these misgivings, Lewis still seems to have allowed Havard to advise him on how to cope with his prostate troubles, including letting Havard design the catheter. The frequent malfunctions of this improvised device caused inconvenience and occasionally chaos to Lewis’s social life, as at an otherwise dull Cambridge sherry party which was enlivened with a shower of his urine.

Lewis’s declining last years were not peaceful. Warnie was increasingly prone to alcoholic binges, alleviated but not cured by the loving ministrations of the nuns of Our Lady of Lourdes in Drogheda. The sisters appear to have developed a sentimental soft spot for the routinely dipsomanic retired major, treating him with a well-intentioned indulgence that probably only encouraged his addiction. The Kilns was in poor repair, with damp and mould beginning to make their appearance.

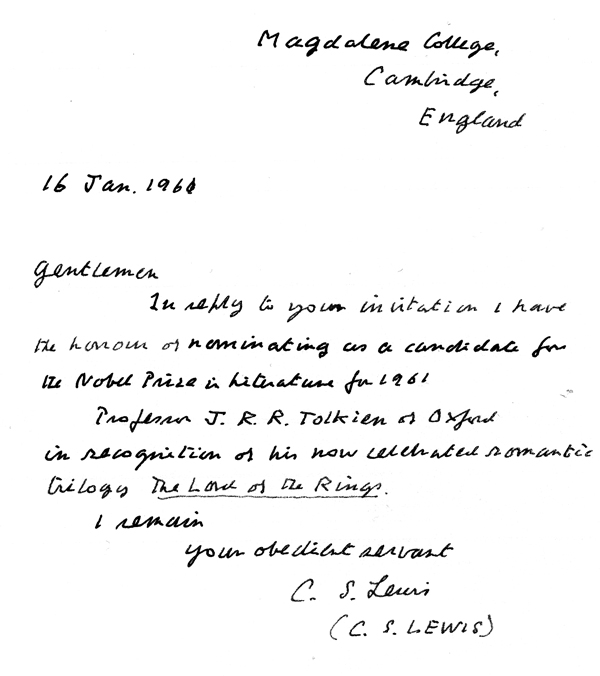

14.2 C. S. Lewis’s unpublished letter of 16 January 1961, nominating J. R. R. Tolkien for the 1961 Nobel Prize in Literature. Copyright © C. S. Lewis Pte. Ltd.

A further concern was the continued cooling of the relationship between Tolkien and Lewis. This, it must be noted, was largely on Tolkien’s side, reflecting his darkening views about Lewis. Yet Lewis never lost his respect or admiration for Tolkien. This is clear from an episode that has only recently come to light. Early in January 1961, Lewis wrote to his former student, the literary scholar Alastair Fowler, who had asked Lewis whether he ought to apply for a chair of English at Exeter University. Lewis told him he should. Then he asked Fowler’s advice. Whom did he think ought to get the 1961 Nobel Prize in Literature?722 The reason for this curious request has now become clear.

When the archives of the Swedish Academy for 1961 were opened up to scholars in January 2012, it was discovered that Lewis had nominated Tolkien for the prize.723 As a professor of English literature at the University of Cambridge, Lewis had received an invitation from the Nobel Committee for Literature in late 1960 to nominate someone for the 1961 prize. In his letter of nomination, dated 16 January 1961, Lewis proposed Tolkien, in recognition of his “celebrated romantic trilogy” The Lord of the Rings.724 In the end, the prize went to the Yugoslavian writer Ivo Andriæ (1892–1975). Tolkien’s prose was judged inadequate in comparison with his rivals, which included Graham Greene (1904–1991). Yet Lewis’s proposal of Tolkien for this supreme literary accolade is an important witness to his continued admiration and respect for his friend’s work, despite their increasing personal distance. If Tolkien ever knew about this development (and there is nothing in his correspondence that suggests he did), it did nothing to rebuild his deteriorating relationship with Lewis.

As if this were not enough, both of Davidman’s sons—now entrusted to the care of Lewis and Warnie—had issues which needed to be resolved, not least concerning their schooling. David, apparently suffering a crisis of identity, had decided to become an observant Jew, reaffirming his mother’s religious roots. This obliged Lewis to find kosher food to enable him to meet his new dietary requirements. (Lewis eventually tracked some down at Palm’s Delicatessen in Oxford’s covered market.) Lewis encouraged David’s reassertion of his Jewish roots, including arranging for him to learn Hebrew rather than the more traditional Latin at Magdalen College School. He sought the advice of Oxford University’s Reader in Post-Biblical Jewish Studies, Cecil Roth (1899–1970), about how to accommodate his stepson’s growing commitment to Judaism.725 It was on Roth’s recommendation that David began his studies at North West London Talmudical College in Golders Green, London.

During the spring of 1963, Lewis’s health recovered sufficiently to allow him to spend the Lent and Easter Terms teaching at Cambridge. By May 1963, he was planning his lectures for the Michaelmas Term. He would deliver a lecture course at Cambridge on medieval literature on Tuesday and Thursday mornings in full term, beginning on 10 October.726

At this point, Lewis developed a friendship which would initially prove to be of critical importance in his final months, and subsequently in reviving interest in him after his death. Lewis had many American admirers with whom he corresponded over the years. One of these was Walter Hooper (1931– ), a junior American academic from the University of Kentucky who had researched his writings and was interested in writing a book on him. Hooper had begun a correspondence with Lewis on 23 November 1954, while serving in the US army, and developed a long-standing interest in Lewis’s work during his subsequent academic career. Hooper had been particularly impressed by a short preface Lewis had contributed to Letters to Young Churches (1947), a contemporary translation of the New Testament Epistles by the English clerical writer J. B. Phillips (1906–1982). Even as early as 1957, Lewis had agreed to meet Hooper if he should ever have cause to visit England.727

In the end, Hooper’s visit was postponed, although their correspondence continued. In December 1962, Hooper sent Lewis a bibliography of Lewis’s published works that he had compiled, which Lewis appreciatively corrected and expanded at several points. He once again agreed to meet with Hooper when Hooper was next in England, and suggested June 1963 as a time when he expected to be at home in Oxford.728 The meeting was finally arranged for 7 June, when Hooper would be in Oxford to attend an International Summer School at Exeter College.

Lewis clearly enjoyed meeting Hooper, and invited him to come along to the next meeting of the Inklings the following Monday. These meetings now took place on the other side of St. Giles, the Inklings having reluctantly transferred from the Eagle and Child to the Lamb and Flag, following renovations which had ruined the privacy and intimacy of the “Rabbit Room.”729 Since Lewis had to be in residence at Magdalene College during term time, the meetings now took place on Mondays, allowing Lewis to take the afternoon “Cantab Crawler” to Cambridge. Hooper, who was an Episcopalian at this point, accompanied Lewis to church at Holy Trinity, Headington Quarry, on Sunday mornings.

Final Illness and Death

Lewis had intended to travel to Ireland in late July 1963 to visit Arthur Greeves. Aware of his declining physical strength, Lewis had arranged for Douglas Gresham to join them, partly to help carry his luggage. On 7 June, when Lewis returned to Oxford at the end of Cambridge’s summer term, Warnie had left for Ireland, assuming that Lewis would join him during the following month. But it was not to be. Lewis’s health deteriorated sharply in the first week of July.

On 11 July, Lewis reluctantly wrote to Greeves to cancel his trip. He had had a “collapse as regards the heart trouble.”730 Lewis was now tired, unable to concentrate, and prone to falling asleep. His kidneys were not functioning properly, allowing toxins to build up in his bloodstream, causing him fatigue. The only solution was blood transfusions, which temporarily eased the situation. (The general use of kidney dialysis still lay some years in the future.)

When Walter Hooper arrived at The Kilns on the morning of Sunday, 14 July 1963 to take Lewis to church, he realised that Lewis was seriously ill. Lewis was exhausted, scarcely able to hold a cup of tea in his hands, and seemed to be in a state of confusion. Worried about his failure to maintain his correspondence in his brother’s extended absence, Lewis invited Hooper to become his personal secretary. Hooper was already signed up to teach a course in Kentucky that fall, but agreed to take the position in January 1964. Lewis, however, possibly confused and unable to concentrate fully, failed to explain what kind of financial arrangement he had in mind to recompense Hooper for his work, or what formal expectations he had for his new employee.

On the morning of Monday, 15 July, Lewis wrote a short letter to Mary Willis Shelburne, explaining how he had lost all mental concentration, and would be going into the hospital that afternoon for an examination and evaluation of his condition.731 Lewis arrived at the Acland Nursing Home at five o’clock that afternoon, and suffered a heart attack almost immediately after his arrival. He fell into a coma, and was judged to be close to death. The Acland informed Austin and Katharine Farrer, having failed in their efforts to contact Lewis’s next of kin—Warnie.732

The next day, Austin Farrer made the decision that Lewis, who was being kept alive with an oxygen mask, would wish to receive the last rites. He arranged for Michael Watts, curate of the Church of St. Mary Magdalen, a few minutes’ walk from the Acland Nursing Home, to visit Lewis for this purpose. At 2.00 p.m., Watts administered the last rites. An hour later, to the astonishment of the medical team, Lewis awoke from his coma and asked for a cup of tea, apparently unaware that he had been unconscious for the better part of a day.

Lewis later told his friends that he wished he had died during the coma. The “whole experience,” he later wrote to Cecil Harwood, was “very gentle.” It seemed a shame, “having reached the gate so easily, not to be allowed through.”733 Like Lazarus, he would have to die again. In a more extended comment in his final letter to his confidant Arthur Greeves, he remarked:

Tho’ I am by no means unhappy I can’t help feeling it was rather a pity I did revive in July. I mean, having been glided so painlessly up to the Gate it seems hard to have it shut in one’s face and know that the whole process must some day be gone thro’ again, and perhaps far less pleasantly! Poor Lazarus! But God knows best.734

Lewis had remained in regular correspondence with Greeves since June 1914—one of the most significant and intimate relationships of his life, which few of his circle knew anything about until the publication of Surprised by Joy revealed their youthful friendship (though not its prolonged extension into the present). Characteristically, Lewis apologised for the consequences of his condition: “It looks as if you and I shall never meet again in this life.”

Although Lewis enjoyed two days of mental clarity after awakening from his coma, he then entered a dark period of “dreams, illusions, and some moments of tangled reason.”735 On 18 July, the day on which these delusions began, Lewis was visited by George Sayer, who was disturbed to find him so very confused. Lewis told Sayer that he had just been appointed Charles Williams’s literary executor, and urgently needed to find a manuscript hidden under Mrs. Williams’s mattress. The problem was that Mrs. Williams wanted a vast sum of money for the manuscript, and Lewis didn’t have the ten thousand pounds she was demanding. When Lewis began to talk about Mrs. Moore as if she were still alive, Sayer realised that Lewis was delusional. When Lewis then told him that he had asked Walter Hooper to be his temporary secretary to handle his correspondence, Sayer not unreasonably assumed this was also a delusion.736

Once Sayer realised that there really was a Walter Hooper, outside the dark hallucinatory realm that Lewis was occupying at that time, and that Hooper would be able to help look after Lewis, he decided that he ought to travel to Ireland to track down Warnie. In the end, Warnie turned out to be in such a bad state of alcohol poisoning that he was incapable of understanding what had happened to Lewis, let alone contributing to the amelioration of the situation. Sayer returned alone to Oxford.

On 6 August, Lewis was allowed to return to The Kilns, under the care of Alec Ross, a nurse provided by the Acland. Ross was used to caring for wealthy patients in their well-appointed homes, and was shocked by the squalid conditions he found at The Kilns, particularly its filthy kitchen. A major cleanup began, to make the house habitable. Lewis was forbidden to climb stairs, and so had to be accommodated on the ground floor. Hooper took over Lewis’s old upstairs bedroom and acted as secretary to Lewis. Among the more pathetic missives Hooper wrote on behalf of Lewis at this point were Lewis’s letters of resignation from his chair at Cambridge University and his fellowship at Magdalene College.

But how was Lewis to move all his books from Cambridge? He was totally unable to travel. On 12 August, Lewis wrote to Jock Burnet, the bursar of Magdalene College, informing him that Walter Hooper would be coming to Cambridge on his behalf to remove all the possessions from his room. The following day, Lewis penned an even more pathetic missive, telling Burnet that he was free to sell anything that remained. Walter Hooper and Douglas Gresham turned up at Magdalene on 14 August, armed with seven pages of detailed instructions from Lewis concerning his possessions. It took them two days to sort things out. On 16 August, they returned to The Kilns in a truck containing thousands of books, which were stacked in piles on the floor until space could be found for them in bookcases.

In September, Hooper returned to the United States to resume his teaching responsibilities, leaving Lewis to be cared for by Paxford and Mrs. Molly Miller, Lewis’s housekeeper. Lewis was clearly anxious about his own situation. Where was Warnie, and when would he return? Sadly, Lewis concluded that Warnie had “completely deserted” him, despite knowing the seriousness of his condition. “He has been in Ireland since June and doesn’t even write, and is, I suppose, drinking himself to death.”737 Warnie had still not returned by 20 September, when Lewis wrote a somewhat furtive letter to Hooper to clarify the nature of his future employment.

It is clear that Lewis had not given proper thought to what he wished Hooper to do in his role as his private secretary, nor how he would pay for this.738 When Hooper wrote to broach the subject of a salary for his proposed employment, Lewis somewhat shamefacedly confessed that he just didn’t have the funds to pay him, offering plausible yet weak excuses. Having resigned his chair, he no longer had a salary. And what if one of the Gresham boys needed money?739 Having Hooper as a “paid secretary” would be a luxury that he just couldn’t afford. But if Hooper could afford to come over in June 1964, he would be most welcome. The unspoken assumption seems to have been that Hooper would be funding himself.

We see here one of the matters that preyed heavily on Lewis’s mind after the resignation of his Cambridge chair—money. Lewis continued to live in fear of tax demands that he might not be able to pay. His income was limited to royalties from his books. This was quite substantial at the time; yet Lewis was convinced that they would soon decline as interest in his works waned. His anxieties about his financial future were clearly fuelled in September by his loneliness. He had no soul mate with whom to share his worries.

A month later, Lewis wrote again to Hooper, bringing the good news that Warnie had finally returned.740 Lewis, it soon became clear, was still anxious about his finances. He was not sure what he could pay Hooper—if anything. His best offer was that Hooper could live at The Kilns, where they would have to share a fire and a table. Then there was the problem of Warnie, who might resent Hooper’s presence. The most Lewis could afford to pay Hooper was five pounds a week—fourteen dollars.741 It was hardly an attractive prospect. In the end, however, Hooper agreed to come. His arrival was scheduled for the first week of January 1964.742

In the middle of November, Lewis received a letter from Oxford University which can be seen as a sign—if a sign were indeed needed—marking a rehabilitation of his reputation there. He was invited to deliver the Romanes Lecture in the Sheldonian Theatre, perhaps the most prestigious of Oxford University’s public lectures. With great regret, Lewis asked Warnie to write a “very polite refusal.”743

Friday, 22 November 1963, began as usual in the Lewis household, Warnie later recalled: after they had breakfast, they turned to the routine answering of letters, and tried to solve the crossword puzzle. Warnie noted that Lewis seemed tired after lunch, and suggested that he go to bed. At 4.00, Warnie brought him a cup of tea, and found him “drowsy but comfortable.” At 5.30, Warnie heard a “crash” from Lewis’s bedroom. He ran in to find Lewis collapsed, unconscious, at the foot of the bed. A few moments later, Lewis died.744 His death certificate would give the multiple causes of his death as renal failure, prostate obstruction, and cardiac degeneration.

At that same time, President John F. Kennedy’s motorcade left Dallas’s Love Field Airport, beginning its journey downtown. An hour later, Kennedy was fatally wounded by a sniper. He was pronounced dead at Parkland Memorial Hospital. Media reports of Lewis’s death were completely overshadowed by the substantially more significant tragedy that unfolded that day in Dallas.

Warnie was overwhelmed by his brother’s death, which triggered another alcoholic binge. He refused to let anyone know when the funeral was taking place.745 In the end, Douglas Gresham and others telephoned a few key friends to let them know the arrangements. While Warnie spent Tuesday, 26 November in bed drinking whisky, others gathered on that cold, frosty, sunlit morning to bury Lewis at Holy Trinity Church, Headington Quarry, Oxford. There was no funeral procession into the church; Lewis’s coffin had been brought to the church the previous evening. No public announcement was made of the funeral. It was a private affair, attended by Lewis’s circle of friends—including Barfield, Tolkien, Sayer, and the president of Magdalen College. The service was led by the vicar of Holy Trinity, Ronald Head. Austin Farrer read the lesson. There being no immediate family present, the small funeral procession from the church into the graveyard was headed by Maureen Blake746 and Douglas Gresham, who followed the candle bearers and processional cross into the churchyard, where the freshly dug grave awaited them.747

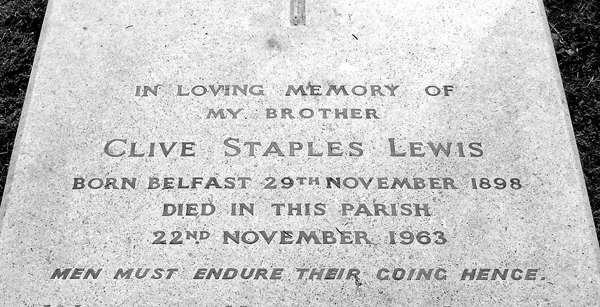

14.3 The inscription on Lewis’s gravestone in the churchyard of Holy Trinity, Headington Quarry, Oxford.

The rather melancholic text Warnie chose for his brother’s gravestone was that displayed on the Shakespearean calendar in Little Lea on the day of their mother’s death in August 1908: “Men must endure their going hence.” Yet perhaps some of Lewis’s own words, penned a few months earlier, capture both his style and his hope in the face of his inevitable death somewhat better than this severe and forbidding epitaph. We are, Lewis suggested, like

a seed patiently waiting in the earth: waiting to come up a flower in the Gardener’s good time, up into the real world, the real waking. I suppose that our whole present life, looked back on from there, will seem only a drowsy half-waking. We are here in the land of dreams. But cock-crow is coming.748