CHAPTER 5

1927–1930

Fellowship, Family, and Friendship: The Early Years at Magdalen College

Magdalen College, Oxford, was founded in 1458 by William Waynflete (ca. 1398–1486), Bishop of Winchester and Lord Chancellor of England. As the bishop of a wealthy diocese, and without any close family, Waynflete saw the endowment of Magdalen College as his personal project. Over a period of twenty years, Waynflete showered his new college with buildings and assets. When Waynflete drew up Magdalen’s first statutes in 1480, the college was wealthy enough to support forty fellows, thirty scholars, and a chapel choir. Few Oxford or Cambridge colleges could hope to be so well endowed. When Lewis took up his fellowship, Magdalen was still—along with St. John’s—widely regarded as the richest of the Oxford colleges.

Fellowship: Magdalen College

Lewis was formally admitted to his fellowship at Magdalen in a ceremony in August 1925. The entire fellowship of the college assembled to witness his admission, following the ancient tradition. Lewis was required to kneel before the president as a long Latin formula was read out. The president then lifted Lewis to his feet, addressing him with the words, “I wish you joy.” The dignity of the occasion was somewhat spoiled when Lewis clumsily tripped over his gown. Happily, he recovered from this disaster, and slowly worked his way around the room so that everyone present might personally wish him “joy,” while clearly wishing they were somewhere else.256 The reader might linger over that repeated word joy, given its significance for Lewis.

Lewis actually took up his fellowship on 1 October. After spending more than two weeks with his father in Belfast, Lewis returned to Oxford to move into a set of rooms in Magdalen’s New Building (1733), a magnificent eighteenth-century Palladian structure which was originally intended to be the north side of a new quadrangle, but in the end remained standing alone in splendid isolation. Lewis was allocated room 3 on staircase III, a set of rooms consisting of a bedroom and two sitting rooms. The larger of the sitting rooms looked north over Magdalen Grove, home to the college’s herd of deer. The bedroom and smaller sitting room faced southwards, giving Lewis a magnificent view over a lawn to the main college’s buildings and famous tower. It is no exaggeration to say that Lewis had managed to secure one of the most beautiful views in Oxford.

The character of Magdalen College at this time had been shaped by Sir Herbert Warren—affectionately known as “Sambo” to the fellows—who had been elected president of the college in 1885 at the age of thirty-two. Warren would not retire until 1928, and over the forty-three years of his presidency, he moulded the college in his own likeness. Perhaps one of the most striking features of the academic culture established by Warren was Magdalen’s “almost exaggerated collegiality and communal living.”257 Fellows were strongly encouraged to lunch and dine together. Bachelor fellows living in college—such as Lewis—would also breakfast together.258 Lewis had become part of a community of scholars.

5.1 The president and fellows of Magdalen College, July 1928. This photograph was taken to mark the retirement of Sir Herbert Warren (centre front) as president of the college. Lewis is standing to the right of Warren in the back row.

Where some colleges allowed their fellows to lunch or dine privately in their rooms, Warren insisted on fellows sharing meals, seeing this as a way of developing the corporate identity of the college and reinforcing its social hierarchy. At college dinner, fellows were required to process in gowns into Hall from the Senior Common Room in order of seniority. Their seats at High Table were likewise allocated according to seniority, and the familiar use of forenames was avoided. Fellows would refer to each other by surname or by office—“Mr. Vice-President,” “Senior Fellow,” or “Science Tutor.”259

The complex social and intellectual machinery of Oxford University at this time was lubricated by vast quantities of alcohol. Magdalen was perhaps one of the most bibulous of Oxford’s colleges, with its resident fellows being particularly prone to overindulgence. During 1924 and 1925, the Senior Common Room paid off a debt by selling twenty-four thousand bottles of port, raising the sum of £4,000.260 Fellows who wagered against each other would calculate their winnings in terms of cases of claret or port, rather than cash. The Senior Common Room butler was once observed carrying a silver tray laden with brandy and cigars through the college cloisters at eleven o’clock one morning. On being asked what he was doing, the butler replied that he was bringing one of the fellows his breakfast. Lewis kept a barrel of beer in his rooms to entertain colleagues and students, but otherwise seems to have avoided the alcoholic excesses of the prewar years.

President Warren’s trenchant views on collegiality shaped Lewis’s weekly routines. By January 1927, Lewis had perfected his regular working pattern. Outside university Full Term, he would reside at Hillsboro, and take a bus into college, where he remained during working hours, lunching in college. During university Full Term, Lewis slept in college, and bussed home to be with “the family” for the afternoons when he had no teaching or administrative responsibilities. He would return to Magdalen in the late afternoon, and dine with his colleagues.

Lewis was paid a salary of £500 a year as an official tutorial fellow. It was a generous stipend, at the top of the range for fellows of the college. Had Lewis been elected a fellow by examination, he would have enjoyed only half that amount.261 However, it soon became clear that college life at Magdalen would turn out to be rather more expensive than Lewis had anticipated. For a start, his rooms were devoid of any furniture or carpets. Lewis found two, and only two, items already present in his rooms: a washstand in his bedroom, and some linoleum in his smaller sitting room. He would have to furnish his rooms completely at his own expense. In the end, Lewis had to spend £90—a substantial sum in those days—buying carpets, tables, chairs, a bed, curtains, coal boxes, and fire irons. It was a massive and unexpected expense, even though Lewis economised wherever possible by buying secondhand goods.262

Furthermore, Lewis regularly received demands from the college bursary for “Battels”—Oxford’s arcane term for college expenses incurred, such as meals and drink. Lewis confided to his diary that Mrs. Moore was far from happy when she discovered that he was receiving rather less income than he had led her to expect. After some rather awkward conversations with James Thompson, the college’s home bursar, Lewis began to realise that, after deductions, he would actually be taking home about £360 annually.263 And then there was still income tax to pay.

5.2 The New Building, Magdalen College, around 1925.

Lewis broke off his diary after a long entry for 5 September 1925 and did not resume until 27 April 1926. It is not difficult to work out why. Lewis was settling into a new way of life, with new colleagues to meet and a new institution whose workings he needed to understand. He had new lecture courses to prepare and tutorials to give. His tutorial work in philosophy was undemanding and uninteresting. Harry Weldon, Magdalen’s philosophy don, was inclined to dump the less interesting and less able pupils on Lewis, keeping the best students for himself. Yet the bulk of Lewis’s work consisted in giving lectures and tutorials in English literature, as well as teaching textual criticism to research students. There were few students reading English (and thus requiring tuition) at Magdalen at this time. But Lewis was still required to work up a new course of intercollegiate lectures in English literature, which he found very demanding.

Lewis taught undergraduates at Magdalen (and other colleges by arrangement) in tutorials. This teaching method, characteristic of both of England’s “ancient universities” of Oxford and Cambridge, typically involved a single student reading an essay to a tutor, followed by discussion and criticism. Lewis quickly developed a reputation as a harsh and demanding tutor, although this mellowed over time. The 1930s are generally regarded as Lewis’s golden period of teaching at Oxford, by which time he had perfected his lecturing and tutorial techniques.264

His early years, however, were marked chiefly by his impatience at the laziness and lack of perceptiveness on the part of his students, such as John Betjeman (1906–1984). Many of them seemed to regard their time at Oxford as an inebriated extension of their bawdy, lazy schooldays. It was no coincidence that the author P. G. Wodehouse (1881–1975) placed his immensely likable (yet equally lazy and slow-witted) character Bertie Wooster (author of “What the Well-Dressed Man Is Wearing” in Milady’s Boudoir) as an undergraduate at Magdalen just before the time of Lewis’s arrival.

Family Rupture: The Death of Albert Lewis

The death of Lewis’s mother in 1908 had marked a turning point in Lewis’s life. Lewis adored his mother, who was the anchor and foundation of his life. As we have seen, he came to despise and deceive his father. An X-ray of 26 July 1929 gave Albert Lewis’s doctors cause for concern, and led Lewis’s father to enter a comment in his pocket book: “results rather disquieting.”265 Early in September 1929, Albert Lewis was admitted to a nursing home at 7 Upper Crescent, Belfast. An exploratory operation revealed that he had cancer, although it was considered not to be sufficiently advanced to warrant immediate concern.

5.3 The last known photograph of Albert Lewis, 1928.

Lewis had travelled to Belfast to be with his father, arriving on 11 August. He found it to be a tedious business. He wrote to his close friend Owen Barfield, making his negative feelings towards his father disturbingly clear: “I am attending at the almost painless sickbed of one for whom I have little affection and whose society has for many years given me much discomfort and no pleasure.”266 Even though he had no affection for his father, he was finding his father’s deteriorated condition unbearable. What, he wondered, would it be like to attend the deathbed of someone you really loved?

Lewis decided that his father’s condition was stable enough to permit him to return to Oxford on 21 September.267 He had no desire to stay with his father, and there seemed no point in doing so. He had work to do in Oxford to prepare for the beginning of the new academic year. This understandable decision turned out to be a misjudgement. Two days later, his father lost consciousness and then died from an apparent brain haemorrhage, possibly a complication arising from the operation, rather than from the cancer itself. Lewis, having been notified of his father’s turn for the worse, hurried back to Belfast from Oxford, but failed to arrive in time. In the end, Albert Lewis died on Wednesday, 25 September 1929, alone in the nursing home, unaccompanied by either of his sons.268

The two leading city newspapers—the Belfast Telegraph and the Belfast Newsletter—published extensive obituaries of Albert Lewis, recalling his outstanding professional reputation and deep love for literature. It was easy to understand Warnie’s absence at his father’s death; after all, he was serving in the army, stationed far away in Shanghai. There was no way he would have been able to return from the Far East in time.

Where most would see Lewis’s attitude towards his father as strained but dutiful, others believed that the esteemed solicitor had been let down by his younger son, who had compounded his lamentable decision to leave Ireland by not being with his father in his final hours.

Albert Lewis had supported his younger son financially for six long years, and some in Belfast seem to have felt that he deserved better at Lewis’s hands. Canon John Barry (1915–2006), a former curate of St. Mark’s, Dundela—where Albert Lewis’s funeral took place on 27 September 1929—recalls a “sort of chill” later occasioned in certain Belfast circles by the mention of C. S. Lewis’s name, apparently on account of lingering resentment over the way he had treated his father.269 People have long memories in Belfast.

Lewis unquestionably felt both pain and guilt at his father’s death for much of the remainder of his life. There are hints of this at numerous points in his letters, especially in the dramatic opening sentence of a letter of March 1954: “I treated my own father abominably and no sin in my whole life now seems to be so serious.”270 Some agree with this criticism; others, however, feel that it is overstated.

It is important to see this episode against the cultural background of the time in Belfast, particularly concern over sons who had left their parents to seek their fortunes in England. Yet Lewis did not choose to be educated in England; his father made that decision for him, thus laying the foundation for his younger son’s career at Oxford. A sympathetic reading of Lewis’s correspondence around this period indicates that his sense of duty towards his father took precedence over any absence of affection. Lewis spent six long weeks with his father in the summer of 1929, away from “the family,” and was unable to get work done to prepare for the new academic year at Oxford University. He needed to get home, and he justifiably believed his father was out of danger. Lewis returned to Ireland the moment he knew things had turned out badly.

During his brief stay in Belfast around the time of his father’s funeral, Lewis came to certain decisions. Although his father’s will had appointed both sons as executors and sole beneficiaries, Warnie’s enforced absence in China meant that Lewis would have to act on their joint behalf in making certain legal decisions. Most important, Little Lea would have to be sold, though Lewis delayed on this. He sacked the gardener and housemaid, while retaining Mary Cullen—whom Lewis affectionately dubbed the “Witch of Endor”—as housekeeper until the house was sold. The decision to postpone selling the house was an uneconomic one, not least because the house would deteriorate over the winter, reducing its potential sale value. Yet Lewis felt he had to wait for the return of his brother before making any final decisions about the disposal of the contents of the house.271

Warnie finally returned on leave from Shanghai on 16 April 1930 and stayed with Lewis and Mrs. Moore in Oxford. Little Lea had not yet found a buyer. Lewis and Warnie travelled to Belfast to visit their father’s grave, and make their final joint visit to the memory-laden house. Both brothers found their visit to their former home depressing, partly on account of its state of decay, and partly on account of the irretrievable memories linked to it. Overwhelmed by the “intense stillness” and “utter lifelessness” of the rooms,272 the brothers solemnly buried their toys in the vegetable patch. It was a sad and forlorn farewell to their childhood, and the imaginary worlds they had once constructed and inhabited. In the end, Little Lea sold for £2,300—substantially less than they had anticipated—in January 1931. It was the end of an era.

The Lingering Influence of Albert Lewis

Lewis might have secured closure on his father in a legal and financial sense. Yet there is every reason to think that in Lewis’s own later years, he came to see his attitude towards his father in his declining years as reprehensible. Lewis secured emotional closure on the issue in his own characteristic way—by writing a book. Although Surprised by Joy can be read as a spiritual autobiography, rich in Lewis’s memories of his own past and the shaping of his inner world, it clearly played another role: it allowed Lewis to come to peace with his past behaviour.

In a letter written to Dom Bede Griffiths in 1956, shortly after the publication of Surprised by Joy, Lewis reflected on the importance of being able to discern patterns in an individual’s life. “The gradual reading of one’s own life, seeing the pattern emerge, is a great illumination at our age.”273 It is difficult to read Lewis’s autobiographical reflections without bearing this point in mind. For Lewis, the narration of his own story was about the identification of a pattern of meaning. This enabled him to grasp the “big picture” and discern the “grand story” of all things, so that the snapshots and stories of his own life could assume a deeper meaning.

Yet the next sentence in this letter to Griffiths discloses a deeper concern that Lewis clearly saw as significant: “getting freed from the past as past by apprehending it as structure.” The close reader of Surprised by Joy will note the omission or marginalization of three extended issues that clearly caused Lewis emotional difficulty for much of his later life.

First, and perhaps most famously, he makes it clear that he is honour bound not to mention Mrs. Moore, despite the enormous role she played in his personal history. “Even were I free to tell the story,” he writes, “I doubt if it has much to do with the subject of the book.”274

The second notable feature is the relative absence of reference to the suffering and devastation of the Great War, which created intellectual havoc in the minds and souls of so many. We have drawn attention to this point earlier in this narrative, and it is important to understanding Lewis’s development, both as a scholar and as a Christian apologist. Where some have argued that Lewis’s rediscovery of religious faith can be seen within a broadly psychoanalytic narrative thread that gives unity to Lewis’s development, the evidence does not warrant such a conclusion. The real issue lies in the destruction of the fixed certainties, values, and aspirations of an earlier generation by the haunting memories of the horrors of the mass carnage of modern warfare—a theme that pervades much English literature of the 1920s.

The third understatement concerns the death of Albert Lewis in 1929. This, Lewis declares, “does not really come into the story” he wants to tell.275 Perhaps Lewis deemed it irrelevant. Perhaps it was also too painful to discuss. How much are we to read into a section of Lewis’s later essay “On Forgiveness” (1941), in which he emphasises the need to accept that we have been forgiven, even though we believe ourselves to be unforgivable? In inviting his audience to reflect on the need to acknowledge human failings, Lewis gives some examples of persistent behaviours that need constant forgiveness. One stands out to all who know Lewis’s personal history: the “deceitful son.” “To be a Christian means to forgive the inexcusable, because God has forgiven the inexcusable in you.”276

One of the major themes of Till We Have Faces (1956)—arguably the most profound piece of fiction written by Lewis—is the difficulty of coming to know ourselves as we really are, and the deep pain that such knowledge ultimately involves. Perhaps we ought to read Surprised by Joy with this point in mind. The suppression of certain themes in Lewis’s account of his own development is not a mark of dishonesty, but of the pain their memory engendered.

There is one particular point that puzzles the reader of Lewis’s correspondence around the time of his father’s death. In Surprised by Joy, Lewis tells us he began to actively believe in God at some point during Oxford’s “Trinity Term of 1929”277—at least three months, and possibly five, before his father’s death. Yet at no point in his correspondence around the time of his father’s death—or, indeed, for the six months following—does Lewis mention this belief, or speak of deriving any consolation from it.

Lewis did not regard his father with great affection, and seems to have found his passing a relief rather than a trauma. Yet this absence of reference to God around this time is as conspicuous as it is curious. It does not fit well into Lewis’s own chronology of his conversion. Might it be that the death of Albert Lewis actually caused Lewis to explore the question of God, instead of being something that Lewis interpreted in the light of such a belief? Might his father’s death have prompted Lewis to ask deeper—and as yet unanswered—questions about life, and search for more satisfying answers? We shall return to this question in the following chapter, where we shall raise further concerns about the traditional understanding of Lewis’s journey from atheism to Christianity.

Family Reconnection: Warnie Moves to Oxford

In 1930, Lewis’s domestic arrangements changed significantly. As we have seen, following the death of their father in September 1929, the two Lewis brothers were left as sole heirs to Little Lea. Lewis had corresponded with his brother, Warnie, in Shanghai in January 1930 about the difficult and painful matter of placing their childhood home on the market. Warnie wanted to visit the house for one last time before it was sold; Lewis wanted to get it sold as soon as possible, while realising that an early sale would prevent his brother from making such a sentimental visit.278

It is clear that another possibility was beginning to emerge in Lewis’s mind: the re-creation of the brothers’ shared childhood “Little End Room” of “Little Lea” in Oxford. What if Warnie were to move in with Lewis when he left the army—perhaps by using one of Lewis’s set of rooms at Magdalen? Or perhaps by joining with Mrs. Moore and getting a larger house than Hillsboro? Mrs. Moore, it must be emphasised, appears to have been actively supportive of this latter, more ambitious possibility. It was a natural outcome of her intrinsically hospitable nature. Warnie would not be their guest, but an integral part of their household—their family.

In raising this possibility with his brother, Lewis emphasised that this would have drawbacks. Would he be able to abide by their indifferent “cuisine”? With Maureen’s frequent “sulks”? With “Minto’s mare’s nests”? Yet there was no concealing that Lewis wanted Warnie to be part of his family life. “I have definitely chosen and don’t regret the choice. What I hope—very much hope—is that you, after consideration, may make the same choice, and not regret it.”279

In May 1930, Warnie made two decisions. First, he would edit the papers of the Lewis family, as a way of paying homage to his parents; second, he would move into Hillsboro with his brother and his brother’s family as soon as it was possible. Another possibility was developing even as Warnie made his decision—the purchase of a new and larger house. Up to this point, Lewis and Mrs. Moore had rented properties together. But Lewis’s fellowship had been renewed after its initial five years. He was now in a financially stable situation, with the assurance of a regular income for the rest of his working life. He and Warnie could expect to receive a reasonable sum when Little Lea finally sold. Warnie had savings. And Mrs. Moore had inherited a trust fund as a result of the death of her brother, Dr. John Askins. If they pooled their resources, they could purchase a property big enough for them all.

5.4 Lewis, Mrs. Moore, and Warnie at The Kilns during the summer of 1930.

On 6 July 1930, Lewis, Warnie, and “the family” saw “The Kilns” for the first time. It was a somewhat unimpressive, low-lying building in Headington Quarry, close to the foot of Shotover Hill, where Lewis enjoyed walking. Set in eight acres of grounds, the property would need expansion to accommodate four people. Yet all three partners in the enterprise pronounced themselves satisfied with the property, even with all the work that needed to be done. The asking price was £3,500, which was negotiated down to £3,300. Warnie paid the cash deposit of £300, and contributed £500 towards the mortgage. Mrs. Moore’s trustees advanced her £1,500, and Lewis himself added £1,000.280 Two additional rooms were added on shortly afterwards, ready for Warnie’s final return from military service.

The property was held in Mrs. Moore’s name, with each brother having permanent right of occupation during his lifetime. The Kilns was not, strictly speaking, Lewis’s home. He lived there, but did not own it. He had all that he needed—a “Right of Life” tenancy which allowed him and Warnie permanent right of abode until their deaths. On Mrs. Moore’s death in January 1951, title to the property passed to her daughter, Maureen, with both Lewis brothers continuing to have right of abode until their deaths.281 (In the end, free-and-clear title to the house and estates passed to Maureen on the death of Warnie in 1973.)

The Kilns would play a significant role in consolidating Lewis’s life, not least because it provided a stable home for his brother. Warnie embarked from Shanghai on 22 October 1932 on the SS Automedon. He arrived in the port city of Liverpool on 15 December, and then travelled south to Oxford. “It all seems too good to be true!” Lewis wrote to him. “I can hardly believe that when you take your shoes off a week or so hence, please God, you will be able to say ‘This will do for me—for life.’”282 Warnie finally retired from the army on 20 December, although he remained on the reserve list.283 This renewed relationship with his brother, for better or worse (and it was mostly better), would be of critical importance for the remainder of Lewis’s life.284

Yet we must mention another relationship to emerge around this time, which would also be of importance to Lewis: his deepening friendship with John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (1892–1973).

Friendship: J. R. R. Tolkien

Lewis’s teaching responsibilities extended beyond Magdalen. He was a member of Oxford University’s Faculty of English Language and Literature, and delivered intercollegiate lectures on aspects of English literature—such as “Some Eighteenth-Century Precursors of the Romantic Movement.” He also attended meetings of the faculty, which largely consisted of discussing teaching and administrative arrangements. These meetings were held at 4.00 p.m., following afternoon tea at Merton College, the home base of Oxford’s two Merton Professors of English, and were often referred to as the “English Tea.”285

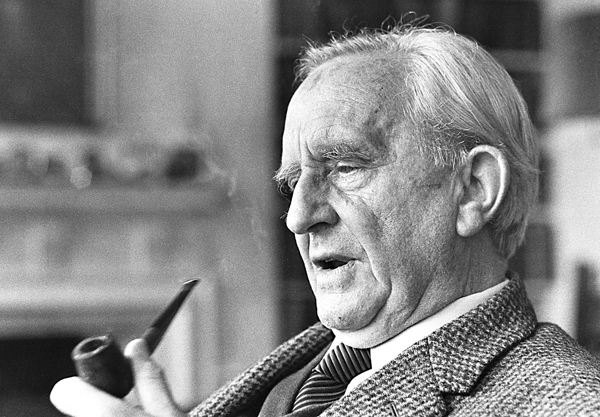

5.5 J. R. R. Tolkien, photographed in his rooms at Merton College in the 1970s. © Billett Potter, Oxford.

It was at an English Tea on 11 May 1926 that Lewis first met J. R. R. Tolkien—a “smooth, pale, fluent little chap,”286 who had joined Oxford’s English faculty as Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon the previous year. Lewis and Tolkien would quickly find themselves embattled over the shape of the Oxford English curriculum. Tolkien argued for a curriculum closely focussed on ancient and medieval English texts, requiring the mastery of Old and Middle English; Lewis believed English was best taught by focussing on English literature after Geoffrey Chaucer (ca. 1343–1400).

Tolkien was prepared to defend his corner, and worked hard to promote the study of forgotten languages. To advance his agenda, he founded a study group he named the Kolbítar, aimed at fostering an appreciation of Old Norse and its associated literature. Lewis became a member.287 The curious term Kolbítar was adopted from Icelandic; it literally means “coal-biters,” and was a derisive term for Norsemen who refused to join in the hunt or fight battles, preferring instead to stay indoors and enjoy the protective warmth of the fire. As Lewis put it, the term (which he insisted is to be pronounced “Coal-béet-are”)288 refers to “old cronies who sit round the fire so close that they look as if they were biting the coals.” Lewis found this “little Icelandic club” a massive stimulus to his imagination, throwing him back into “a wild dream of northern skies and Valkyrie music.”289

The relationship between Lewis and Tolkien is one of the most important of his personal and professional life. They had much in common, in terms of both literary interests and shared experiences of the battlefields of the Great War. Yet Lewis’s correspondence and diary make little save incidental reference to Tolkien until late in 1929. Then evidence of a deepening relationship begins to emerge. “One week I was up till 2.30 on Monday (talking to the Anglo Saxon Professor Tolkien),” Lewis wrote to Arthur Greeves, “(who came back with me to College from a society and sat discoursing of the gods & giants & Asgard for three hours).”290

Something that Lewis said that evening must have persuaded Tolkien to take the younger man into his confidence. Tolkien asked Lewis to read a long narrative poem he had been composing since his arrival in Oxford, titled The Lay of Leithian.291 Tolkien was a senior Oxford academic with a public reputation in the field of philology, but with a personal and intensely private passion for mythology. Tolkien had drawn the curtains aside from his private inner self and invited Lewis into his sanctum. It was a personal and professional risk for the older man.

Lewis could not have known it, but at this point Tolkien needed a “critical friend,” a mentor who would encourage and criticise, affirm and improve, his writing—above all, someone who would force him to bring it to completion. He had had such “critical friends” in the past, in the form of two of his old school friends—Geoffrey Bache Smith (1894–1916) and Christopher Luke Wiseman (1893–1987).292 However, Smith had joined the Lancashire Fusiliers, and died of wounds inflicted in the Battle of the Somme; and Wiseman had drifted from Tolkien after his appointment in 1926 as headmaster of the Queen’s College, Taunton, in England’s West Country. Tolkien was a niggling perfectionist, and he knew it. Indeed, his late story “Leaf by Niggle”—which deals with a painter who can never finish his painting of a tree because of his constant desire to expand and improve it—can be seen as a self-parodying critique of Tolkien’s own difficulties in writing. Someone had to help him conquer his perfectionism. And what Tolkien needed he found in Lewis.

We may safely assume that Tolkien breathed a deep sigh of relief when Lewis responded enthusiastically to the poem. “I can quite honestly say,” he wrote to Tolkien, “that it is ages since I have had an evening of such delight.”293 While we must pause the telling of this particular story as we move on to focus on other matters, it is no exaggeration to say that Lewis would become the chief midwife to one of the great works of twentieth-century literature—Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

Yet in a sense, Tolkien would also be a midwife for Lewis. It is arguable that Tolkien removed the final obstacle that stood in Lewis’s path to his rediscovery of the Christian faith—a complex and important story, which demands a chapter in its own right.