The food we created for The Cecil and Minton’s, and the recipes in this book, are inspired by an Afro-Asian-American flavor profile: a foodway that reflects the depth and breadth of the African diaspora. It’s a new concept, and if you’re not into culinary history, it can be a bit of a head-scratcher. I think the simplest way to put it is that the recipes in this book are a modern take on heritage food. If you grew up in or spent significant time in the West Indies or in China or in Korea, if you’re from Ghana or ever lived in Senegal or South Africa or on the coast of Costa Rica, then this food will remind you of food you ate in those places. I love it when we have guests at the restaurant say, “What did you put in this feijoada? It tastes just like my grandmother’s. Soooo good, but just a little different.” The truth is that people aren’t used to getting that super-impact flavor from food in a fine dining setting. They’re used to getting strong flavors at home or in that little ethnic hidden-gem hole-in-the-wall spot. I love the way the dishes in this cookbook bridge that gap between restaurants and heritage food.

This is Heritage Food.

The biggest compliment

you can give us is that

a dish tastes like

your grandmother’s.

All across America, heritage food is experiencing a renaissance. It brings together everything we’ve developed a passion for: sustainability, farm to table, eating local, thinking global. It’s the kind of food you once could expect to eat only in someone’s home. But now you can go out to a nice restaurant and eat gumbo and cornbread with a great bottle of wine. Chefs now want to cook like their grandmothers. We want to cook heritage food, serve it at the highest level. We want to add our touch, make the dish look pretty, and have it taste amazing with the soul of our grandmothers in it.

I try not to give you something you’ve seen before. I’ve cooked in Ghana and Israel, down South and in Singapore. I grew up in an African diaspora household and I have this formal culinary education. So I look to create dishes that express who I am at a really high level. You take a bite, and you have sweet and tangy and crunchy and sour—ingredients you may recognize on a menu but haven’t had together like this before.

I start with the question “How can I make this fun?” So I put the oxtail meat that I grew up eating in a dumpling wrapper. Then I serve the oxtail dumplings in a bowl with a beautiful green apple curry. I’m like a DJ who loves the mash-up: egg rolls filled with barbecue brisket and edamame, udon noodles with goat meat and West African peanut sauce, roast fish with hominy stew and homemade kimchi. Flavors upon flavors upon flavors.

NOT JUST RISOTTO WITH PEAS

At the Culinary Institute of America, I learned the foundations: Italian cooking, French cooking, and, partly because of the popularity of Spanish chefs like Ferran Adrià, a little bit about cooking from Spain. I think we did one week of Chinese cooking. I didn’t learn about the rich Lowcountry cooking tradition that Alexander brought to life at Cafe Beulah. I didn’t learn about the food of New Orleans or all that a great chef like Leah Chase has contributed to the American culinary tradition. Leah’s restaurant, Dooky Chase’s, was a gathering place for the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s and is still regarded today as the standard-bearer for Creole cuisine in that city.

I remember being in the second or third grade and telling my mother, “I want to be a chef.” She would say, “No, you should be a politician. You should be a doctor. You should be a lawyer.” You know moms. They want the best for you. But maybe if she’d known about someone like Leah Chase, she might have thought a little bit differently about the place I could occupy in the food world.

Culinary school did not do much to help me feel like I could use my history to create great food. I used to call culinary school the food factory. We all dressed the same, we talked the same, we did everything the same. We cooked celery and onions the same. We roasted chicken in the exact same way. There was no thinking outside the box. We were learning the foundations. And I get it, that’s important: You have to have a foundation. But I didn’t see myself in the food. I didn’t know if I ever would.

We talk a lot in the restaurant world about the Indian spice traders and their legacy. But everybody misses that the spice traders came through West Africa and then crisscrossed back through the West Indies—that’s why it’s called the West Indies! When I started to read about all of this, I thought, “Hold on, I’m connected to this personally.” My grandfather is from Barbados. I used to go to the island as a kid. Plantain, roti, curry: These are the foods that I used to eat and now I’m reading about them, as research, for my job, in the encyclopedia. Not only could I draw a line from Barbados to West Africa to India through the spice trade, I could place myself and my family, my own personal history, on that continuum. That was exciting—and inspiring.

When Alexander approached me about cooking with him in Harlem, I was excited about the opportunity to draw on American history to change the landscape of American cuisine. That’s why I’m so excited about this cookbook. If you’re at all like me or my friends, you don’t need another cookbook full of recipes for things like risotto and peas. You want to try familiar ingredients cooked in a different way. You want to try new flavors, new spices, new grains, and new cuts of meat.

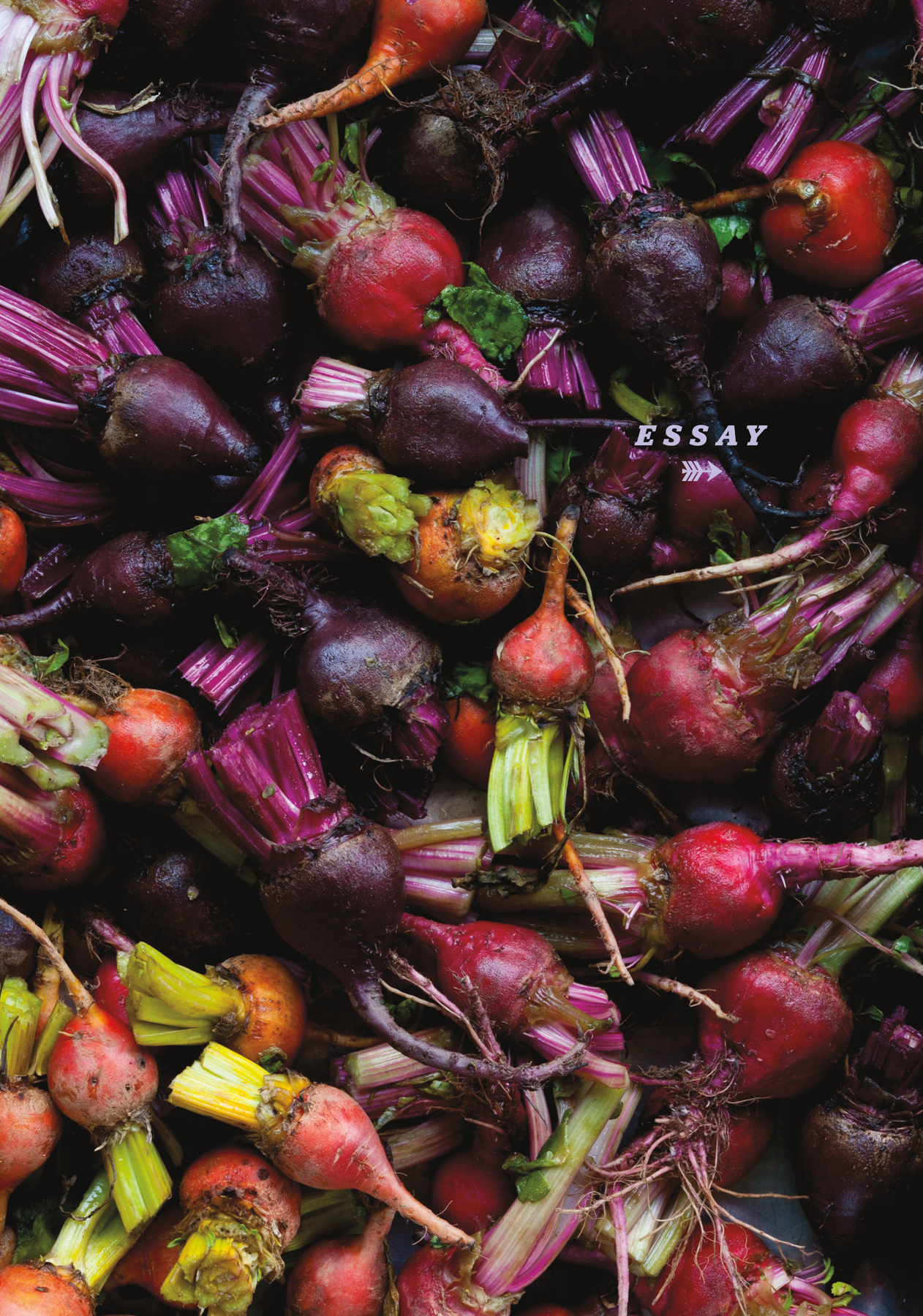

The recipes in this book embrace all the senses. We’re not just focused on look and taste; these are aromatic dishes that you can smell as they approach the table, vividly colored ingredients presented in an array of textures. This comes from our African roots. In West Africa, in particular, people like to smell their food before it comes to the table. If I could have made every page in this book scratch and sniff, I would have! Just check here, look at the picture, and then close your eyes and imagine. That cinnamon-scented guinea hen has been on the menu since our earliest days, and if we ever took it off the menu, our regulars would revolt. I think this will become one of your favorite dishes too: something you break out for Sunday suppers and special gatherings, the kind of dish that greets your guests from the minute they open the door.

In cooking school, we were taught the five French “mother sauces” as defined by the twentieth-century master of French cooking, Auguste Escoffier: béchamel, velouté, sauce espagnole (a simple brown sauce), sauce tomate, and hollandaise. The foundational sauce to the Afro-Asian flavor profile is what we call the Mother Africa sauce: West African peanut sauce. I’d like to urge you to stop reading this book and whip up a batch of it right now.

This is a

sauce that

tastes good

on everything.

You can pour it over a bowl of rice. You can dice up a sweet potato and mix it in as a stew. It tastes delicious with the meat of the chicken thigh crumbled into the mix. This sauce will keep for five days in the fridge and you can eat it every day, in a different way. It’s an easy back-pocket sauce that you can’t mess up. It’s both comfort food and comforting to cook. So give it a try.