Two months later

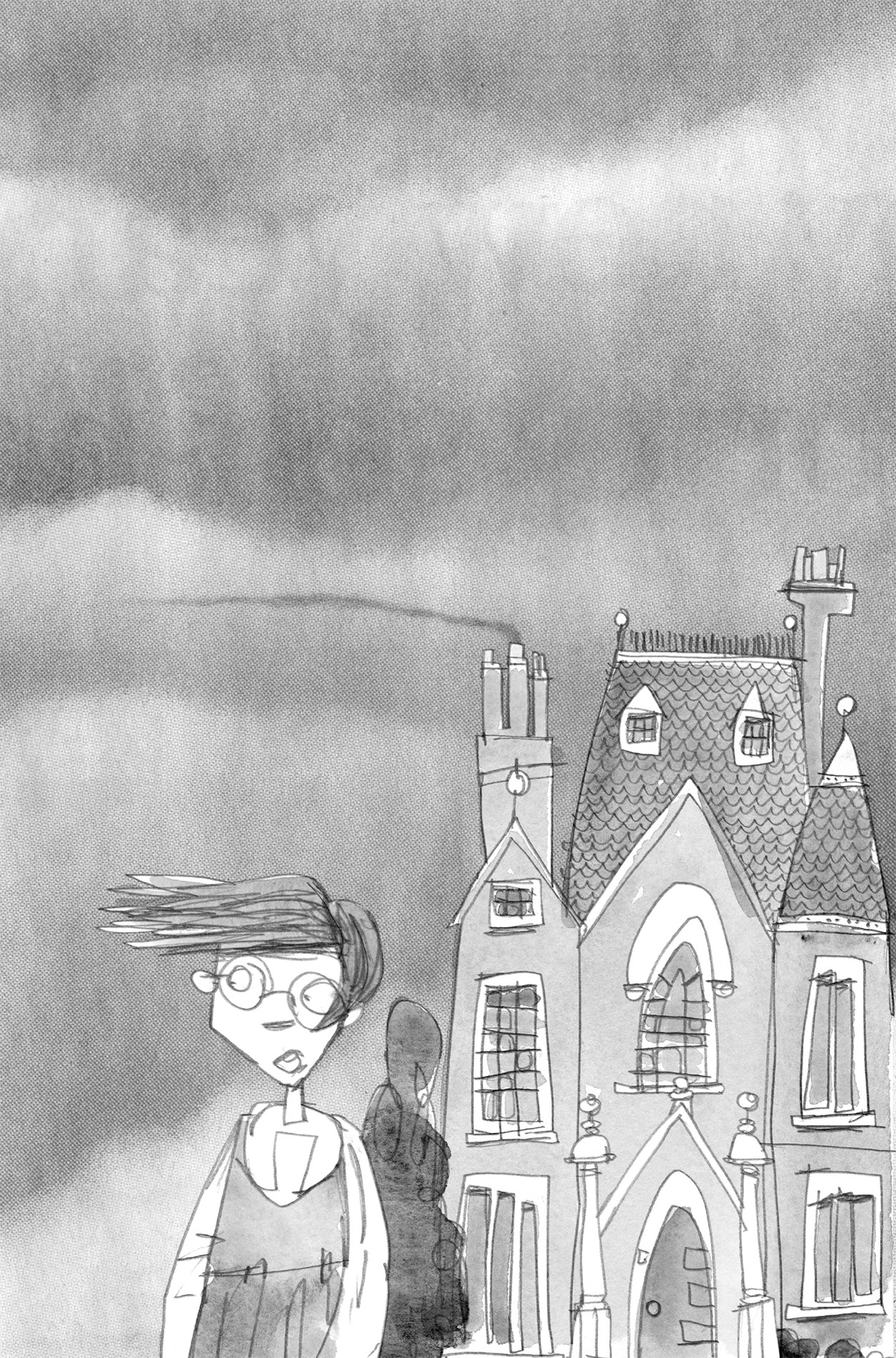

Tig stood on the driveway of St Halibut’s Home for Waifs and Strays, watching the dot that was Maisie the postmistress increase in size as it lumbered towards her up the steep, winding path with their mail. As ever, she marvelled at the dedication of the woman who risked a heart attack by climbing all the way up here every time the orphanage had a single item of post, even if it was just a flyer for one of Ma Yeasty’s regular bakery sales (ten per cent off any muffins more than six months old). If it were Tig’s job, she’d let the letters build up for a couple of weeks and then send one of the town kids to deliver them for her, with the promise of a shiny halfpenny. She allowed herself a small smile. It wasn’t as if she was short of halfpennies anymore. And Maisie could keep her job – she, Herc and Stef weren’t ever going to need one. Just as long as they kept their mouths shut.

A chilly breath of wind lifted her hair and cut a shiver down her back. She wrapped her arms closer about her and eyed the fog that had gathered over the woods below. It crouched over the uppermost branches of the trees, its misty fingers stretching out greedily, now stroking the very edge of Sad Sack. Soon the town would be almost invisible in its grip, which would improve the view from St Halibut’s no end.

The town of Sad Sack resembled nothing so much as a splodge of something unpleasant that should have been mopped up but, left to moulder, had eventually evolved its own life forms. The other local orphanage, St Cod’s Home for Ingrates and Wastrels, festered near its centre, its residents feeding off the unguarded pockets of townsfolk like leeches. The bakery, the library, the butcher’s, the pharmacy that sold incense and strange herbal medicines and smelt so thickly perfumed that the air inside the shop was almost solid in your throat – all were crammed into the winding cobbled streets in haphazard rows that looked like they might fall down if you laid a finger on one of them. But it was the huge Mending House next to St Cod’s that dominated everything. Its stone walls formed a square with one missing side; tall iron railings and gates joined the open section, making a courtyard at the front. It squatted fat and menacing, its bleak chimneys casting murky shadows over all who lived there, the darkness seeming to spread from within its very walls. Tig did not like to look at it.

From the town, the grey stone mansion of St Halibut’s looked the same as it always had – she’d made sure of that. It was beautiful in an unwelcoming sort of way. The same theme continued inside – high ceilings and great big sash windows and old paintings of gammon-faced jowly geezers, all designed to suggest that you weren’t really posh enough to gaze upon it, let alone live there. Miss Happyday had floated about inside, the lady of the manor, as though she and the house were both in denial about the fact that it was also home to scruffy orphans. No one ever ascended the rickety stone steps that led up the steep hillside, apart from Maisie, and occasionally Arfur, who described himself as a travelling curiosity salesman, though he neither travelled much, nor sold anything worth being curious about. Tig knew what he really was, of course: a total slimeball.

Both visitors always came on foot, since the route up had not been fit for horse nor carriage for hundreds of years. It took a good twenty minutes to make the climb, even if you were fit and didn’t stop to catch your breath, and the entire path was in full view of the sweeping drive, so the children were always forewarned of any approach. It was much faster on the way down, as Arfur had once demonstrated when he was drop-kicked off the driveway by Miss Happyday.

Today, Maisie’s good-natured face was as rosy as ever from her exertions. She frequently insisted that each delivery might be her last – not, as Tig suspected, because the hill was going to kill her, but because she had big plans to set up her own knitting business. She’d been delivering the mail for more than twenty years, and had been threatening to stop for nineteen of them. She often brought up her spectacularly garish handmade scarves, socks and hats for the orphans, worrying that they were constantly in danger of hypothermia and needed to be wrapped in as many layers as possible.

‘Love letter for your Miss Happyday, no doubt,’ she told Tig with a wink as she handed over a buff envelope.

The ridiculousness of this idea always raised a smile, no matter that it was an old joke now. If ever the matron of St Halibut’s had attracted feelings of love, they’d been vaporized on contact.

‘Haven’t seen her for an age, and it’s just as well, far as I’m concerned, love. Hope she’s not getting you and the other little ones down?’

‘Not at all.’

‘Ghastly, obnoxious woman. Don’t give her my regards, will you?’

‘I won’t,’ Tig promised as usual.

It was true that the matron was both ghastly and obnoxious, but she could be given no regards even if Maisie had wished it. The last thing she’d been given was two months ago, and that was a good, deep burial under the vegetable garden. The children had even chosen a suitable funeral hymn for the graveside, though it had probably never been intended to be sung quite so cheerfully as it was that day.

‘You keep nice and warm now, in this weather. And make sure that little brother of yours wears his socks. That fog is bitter cold,’ Maisie instructed.

Tig shrugged. ‘It won’t bother us up here.’ Very little did, anymore.

The matron’s death in the freak library collapse had been a shock at first, naturally. Herc claimed that the reason all the shelves had fallen on top of her was that she had been climbing them, but he’d clearly made that up. The only other theory was an earthquake, but that seemed just as unlikely. Why she’d even been there in the middle of the night was also a mystery. But before long the orphans had started calling it the Happy Accident, and after the unfortunate woman’s secret funeral, a shadow lifted from St Halibut’s. It was as though for the first time in the children’s lives, the sun had come out, and they had not until that moment realized they had existed in darkness. A week later, they buried all the hated textbooks too, in a grave even deeper than that of Miss Happyday.

Though Tig wasn’t quite the oldest – that was Stef – it was she who, in the first days of chaos after the death of the matron, had pointed out that their survival depended on bringing some tasks back into their lives, and suggested what might need doing. But it would never be like the matron’s old Schedule; on that they were all agreed. No more spelling tests at 5 a.m., no more ‘playtimes’ spent ironing the matron’s knickers and folding them with the help of a ruler and a ten-step diagram.

After some discussion they had decided it would be best not to rely entirely on trips down to Sad Sack for food, and so the vegetable garden was cared for as it had been before, but anything the children now found to be non-essential was ditched. As time went on, that included the reciting of times tables, the study of grammar, the washing of clothes, the using of cutlery, the making of beds, the brushing of hair and the tidying or cleaning of almost anything. Where once there had been a girls’ dormitory and a boys’ dormitory, they now fell asleep wherever took their fancy. After a wild few weeks of dragging their blankets on to window sills, into the porch and under the kitchen table, they had mostly decided beds were more comfortable, though they arranged them at awkward angles just because Miss Happyday would have been enraged to see them that way.

There was one exception to the general lack of rules, and that was that anyone going down to Sad Sack for supplies must look vaguely presentable to avoid arousing suspicion. On no account could any adult have the slightest inkling that all was not as it should be up on the hill. Even those few who seemed friendly, like Maisie, must be kept strictly in the dark. And so a bath would be filled, a comb found, and a grey St Halibut’s uniform scrubbed and pressed for the occasion, holes darned. The school hat – there was only one tattered example remaining, the others having been used variously for catching cricket balls, nesting birds, and in one case, eaten – was donned before finally each mission to Sad Sack could be undertaken. Usually this job fell to Stef.

Stef, at twelve, was large for his age – thickset and taller than some adults – with hair that looked blue-black indoors but turned chestnut in sunlight. A vivid scar ran from just under his nose, across his mouth, down his chin and all the way to his neck. He had arrived as a two-year-old with this injury, after a tragic horse-and-carriage accident in which he was the only survivor. It had been Miss Happyday who had taken out a needle and thread and sewn Stef ’s face back together, resentment seeping from her every pore. ‘Typical of them to give me the blemished ones,’ she had said as she pressed her lips into a thin line, her needle going in and out in a fury, all her frustration sewed into his hot, red, bawling face. ‘At least you’ll never have cause to be vain.’ Like the others, Stef knew nothing of his parents, although he had gathered that neither was from Sad Sack. Complete strangers seemed to have opinions on the matter – he was frequently asked where he was from and what sort of a name Stef was supposed to be, even once when he was standing in the bakery right next to Ma Yeasty, a woman named after a fungus.

Since Miss Happyday’s untimely demise, Stef had been the only one to occasionally take a bath, filling the tub in the matron’s en-suite bathroom with cold water and heating it with a stove of coals that she had fitted at vast expense for her own personal use. Therefore it was usually he who traipsed down to the town and bought meat from the butcher, tins of beans from the grocer, and more importantly the illegal – and expensive – sweets and biscuits that a few shopkeepers kept secretly under the counter, their sugar content being above the government-approved level.

There was plenty of money, since Miss Happyday turned out to have hoarded a great stash of banknotes under her bed, despite having always complained that she was poor. They’d always known this was nonsense – she clearly had enough to keep herself in comfort, and to keep the house in decent repair. But they were shocked to find that she had been sleeping on top of nearly ten thousand pounds, the sneaky old bat. It was enough to keep the three children in more sherbet lemons and pear drops than they could possibly eat for years to come.

And so, from the outside, St Halibut’s was still your average sinister-looking mansion dedicated to the care and training of abandoned and orphaned children. But on the inside, and in the grounds behind, there was exuberant chaos. It would have given any visitor the kind of shock they could normally only expect if they stood on the roof in a thunderstorm waving an electric eel.

As Maisie was plodding back down the hill, Tig opened the letter and went very still.

What had come in the post was not just an envelope with a message in it. It was the most hideous possible combination of words ever set in ink. A ticking bomb wrapped in horse manure and chucked through the window would have been far more welcome.

Tig held it pinched between her thumb and forefinger, the stiff breeze snapping at the paper as though impatient to dispose of it. She imagined letting go, watching the wind snatch it high over the driveway and the expressionless dark windows of St Halibut’s Home for Waifs and Strays.

She had been a fool to think their happiness would last for long. Three days: that was all that was left of their lives.

She barely heard Stef crunch up the gravel behind her. ‘What’s up?’

There were no words to express the horror.

‘Tig?’

She turned and handed Stef the letter, her jaw clenched.

‘DEATH is coming.’