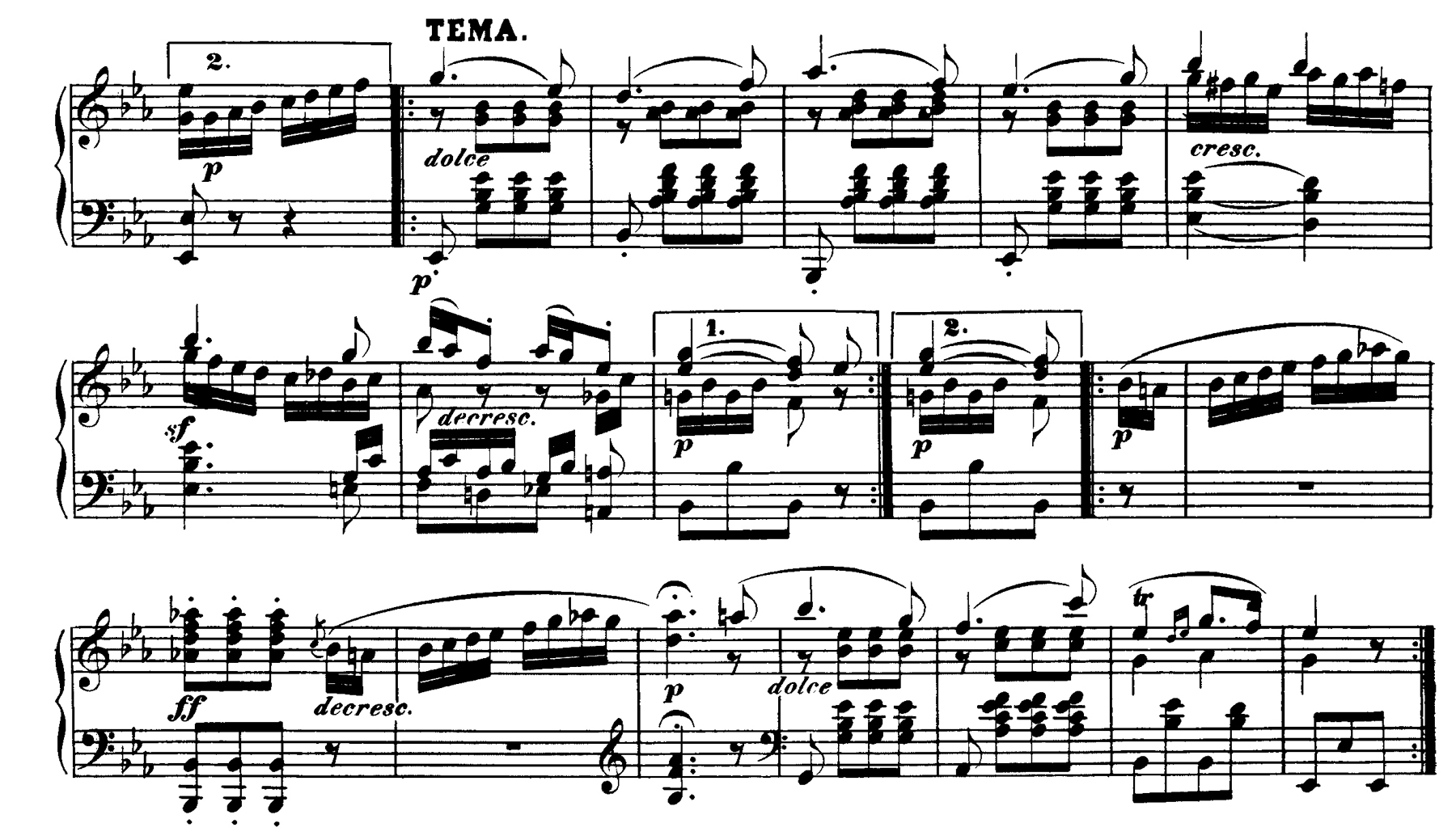

In the ballet’s finale Beethoven worked this simple tune up with contrasting sections, almost as if it were an orchestrated version of one of his bagatelles for piano. It must have had a particular significance for him because once the ballet was out of the way he went straight on to use it yet again, this time for a set of fifteen variations and a fugue for piano. At one level this was a showpiece for Beethoven himself as a virtuoso performer since it is a compendium of pianistic tricks that include hand-crossing, rapid skips and glittering passagework. In this instance the tune, as it first appears, is in the top line:

At another level these taxing variations clearly functioned as a kind of trial run for the ‘Eroica’ Symphony’s Finale, which is based on the same tune used yet again in the same rhythm and key and treated with even greater inventiveness, fugue and all. In fact, the form in both cases is unique in musical history. Never before or since had a set of piano variations started not with the main tune but with a bald, 16-bar statement of its bass line alone:

Thereafter this bare outline gathers accompanying voices until the main theme is finally stated. The symphony’s Finale begins in the same way, only this time it takes 67 bars until the ‘Prometheus’ tune is heard in full. So famous did this theme become as the symphony’s Finale that the earlier piano work is known today as the Eroica Variations, Op. 35, rather than the ‘Prometheus Variations’. The tune’s musical significance is that it perfectly lends itself to almost limitless development and elaboration. Certainly in its earliest version as a little dance tune it gave no hint of the potential for its own apotheosis as a grand symphonic finale.

Unlike the ballet, the piano variations were very well received, and so they should have been given their remarkable originality. Variation 10 in particular, with its impressionistic fragmentation of the theme and its outrageous tonal surprises, inhabits a world akin to that of the Diabelli Variations, Op. 120, of some twenty years later. A critic in the 22 February 1804 issue of the respected Leipzig weekly, Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, was to write a lengthy and admiring review of Op. 35:

Inexhaustible imagination, original humour and deep, intimate, even passionate feeling are the particular features that give rise to the ingenious character that distinguishes nearly all Herr van Beethoven’s works. This earns him one of the highest places among first-rate instrumental composers. His latest works in particular show the care he takes to maintain a chosen character and to combine the greatest freedom with purity of phrasing and contrapuntal elegance. All this composer’s peculiarities just cited can be found to a marked degree in this work. Even its overall form, which deviates so far from what is customary, bears witness to unmistakable genius.3

The ‘deviation’, of course, was the unheard-of idea of starting a set of variations without immediately stating the theme to be varied. Or, rather, without any music critic being quite sure if that really was what Beethoven had done. The absurdly naked bass line that gradually gathers harmonic garments before at last appearing fully clothed as the ‘Prometheus’ tune: might that not actually be the main theme? To this day, nobody can say for certain.

Where the Prometheus myth itself was concerned, Beethoven’s classically educated contemporaries would have spotted the parallels easily enough when eventually they heard the symphony a few years later. Many then no doubt recalled seeing the ballet and recognized its symbolic elements in the symphony’s four movements that one by one outlined the sequence of struggle, death, rebirth and apotheosis. As for the theme’s inner significance to its composer, it is quite difficult for us today not to see this notion of Promethean creativity and punishment as a multiple metaphor. For him the political struggle of the times was intimately tied in with his shifting opinion of Napoleon Bonaparte and France in general. At a private level there was above all his penitential battle with deafness. There would also have been associations with his rescue opera Fidelio, which at the time was constantly and naggingly on his mind. A prisoner being brought up from a Stygian dungeon into bright sunlight was a perfect Promethean motif. And at an obscurer level still there was his struggle as a composer to forge a new music in the teeth of the old, not to mention finally being able to step out of ‘Papa’ Haydn’s shadow.

The Op. 35 Eroica Variations were written at perhaps the most despairing point of Beethoven’s life, and it is extraordinary that their creative energy and even humour betray no hint of this. Beethoven’s new physician, Dr Johann Schmidt, had urged the composer to spare his hearing the din of the big city and retreat to the countryside. So in the summer of 1802 Beethoven took up residence in Heiligenstadt: in those days a pretty hamlet just to the west of Vienna with vistas across the Danube to the Carpathians on the horizon. The rooms he took in a farmhouse had uninterrupted views up a secluded valley behind the house: in fact the very valley he was later to walk while composing the ‘Pastoral’ Symphony. Yet despite the peacefulness of his surroundings, his life’s major crisis was steadily overwhelming him even as he wrote the piano variations. Matters came to a head in early October when he scrawled the despairing document known today as the Heiligenstadt Testament. In the guise of a last will and testament citing his two brothers as joint heirs, it is a cry from the heart: by turns self-pitying, resigned and histrionic. Even today it is impossible to read it without being moved by Beethoven’s depression as he apologizes for having appeared to his family and friends as difficult, morose and misanthropic while all the time not daring to divulge the reason, his darkest secret: that he was going deaf.