CHAPTER THREE

Housing, Feeding, and Guarding Your New Flock

Housing for hobby farm sheep is the essence of simplicity. Sheep are happier and healthier when kept outdoors; you need to provide your flock with well-maintained pastureland. Yet they will also need fencing to keep them safe from predators, simple shelters to protect them from the elements, and pens and stalls for lambing and times of quarantine. Wherever you keep your sheep, you’ll need to make sure they have all the amenities.

Fencing and shelters alone often are not enough to adequately protect your flock. For additional protection, you should consider engaging the help of a guardian animal, whether that be a specially trained dog, a llama, or even a donkey.

LIE DOWN IN GREEN PASTURES

America is a huge country; Minnesota pasture species don’t thrive in the Ozarks, nor do western forage grasses in the Deep South. Again, touch base with your friendly county agricultural extension agent. He can help you choose what’s right for your locale and teach you how to plant and maintain it.

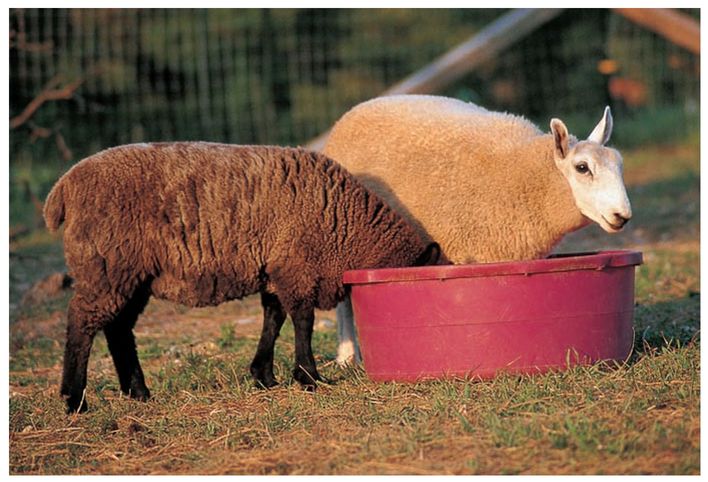

Provide plenty of water in your pasture, and keep it sparkling clean. Sheep won’t drink enough to satisfy their needs if their water supply is alive with green algae or is a scummy mess the flock has pooped in. Don’t just dump and refill the trough; scrub it out. A weak chlorine bleach solution helps chase away stubborn algae deposits. Feed stores sell low, sheep-appropriate fiberglass and metal water troughs, but we prefer injection-molded plastic horse stall cleaning baskets. Heavy-duty plastic cattle and horse mineral lick tubs and pans make dandy, easily cleaned sheep waterers, too. Pastured sheep need shelter from sun, hail, and possibly snow and freezing rain. Trees work fine as sunshades, but your sheep need manmade shelter to withstand harsh storms. If you don’t take your sheep inside at night, make a point of checking them at least twice a day. Count noses. Walk around each sheep, checking for illness or injuries. Patrol all fences and associated structures on a weekly basis, scouting for downed wire, exposed nails, loose tin, wasp nests, and any other accidents waiting to happen.

Lush, green pasture provides essential nutrition for a grazing flock. Given their choice of victuals, sheep choose 40 percent grass and 60 percent browse, meaning they’ll cheerfully rid your meadows and open woodlots of tender tree sprouts, brambles, and briar roses.

Did Ewe Know?

In days of yore, shepherds in Europe were often buried with a tuft of wool in their hands. This practice sometimes signified their devotion to their charges. At other times, it simply showed that they were shepherds—thus excusing occasional lapses in church attendance, because they couldn’t leave their flocks during lambing.

Provide pastured animals with a high-quality, free-choice, granulated sheep mineral mix. Place it inside their shelter, or buy or make a covered container to install outside. Feed a little “sheep candy” every day. A scant handful of corn, pellets, or sweet feed per head keeps them happy to see you, and happy sheep are a whole lot easier to handle.

If your sheep don’t keep weeds and saplings in check, occasionally mow the pasture—or buy a few goats to add to the flock. Constantly grub poisonous plants out of your pastures. Many are bitter, and well-fed sheep won’t eat them—although there are notable exceptions. It takes only a nibble of certain species to dispatch a lamb. It’s best to err on the side of caution.

Our lamb Ewephemia calls to her mother from inside a sturdy, well-ventilated enclosure. The fence is key to the weaning process. Lured in with grain, the flock is released from the enclosure one by one until only the newly weaned lambs remain.

(DO) FENCE ME IN

In most cases, a sheep fence is more important for keeping things out than for keeping them in. Sheep are incredibly easy to fence; one nose-first encounter with electric wire convinces them they want to stay put. Keeping Arkansas coyotes and other predators at bay is another story.

One solution is to coyote-proof nighttime quarters for your sheep. Come sundown, they’ll be in a nighttime fold, with tightly stretched, all-the-way-to-the-ground, woven wire fence surrounding the area. You can reinforce it with strands of electric fence along the top and outside bottom. Should you leave the farm during the day, the sheep can go in then, too. Dogs can be far more lethal than coyotes, and dogs tend to strike during daylight hours. You can purchase a goat companion or two wearing bells to warn of approaching danger.

Some variables to consider when selecting fencing are soil base (for example, rock, sand, or clay), lay of the land, proximity to roadways or neighbors, breed(s) of sheep involved and associated predators from which you want to protect them, available fence-erecting labor, and fencing costs. Fat books have been written about fencing; it’s beyond the scope of this book to discuss the hundreds of types of fencing available in the United States. Before deciding on one, talk to your county agricultural agent and peruse the fine agricultural bulletins available online from the university resources listed in the Appendix of this book. Send for the Premier fencing catalog (contact information also provided in Appendix). If it’s about fencing, it’s in there: which types work where, what each costs, and exactly how to erect it. The energizer (electric fencer) section is an education in itself. If you aren’t already fencing savvy—or even if you are—get the catalog!

Advice from the Farm

Housing and Fences

Our expert sheep advisers talk about housing and fences for sheep.

Housing Hair Sheep

“Although we do have barns and other sheltered areas, most of our sheep don’t use them except on extremely rainy, windy days. They’ll stay out in the rain most of the time. Hair sheep have a thicker skin to compensate for their lack of wool.”

—Connie Wheeler

A Good Pasture

“It’s good to have a hilly pasture where your sheep get lots of exercise going up and down hills to feed and water.”

—Connie Wheeler

Close the Gate!

“My mantra is, ‘Always close all of the gates, all they way, all the time.’ Even if you’re just popping into the pasture to grab a bucket or something. It’s tempting to not always bother. Sometimes you get away with it, but sometimes not.”

—Lisa Maclver

The Ideal Fence

“The ideal fence would be made of the kind of non-climb fencing that equestrians use, although this is quite expensive compared to regular ‘field fence.’ “An electric wire placed away from the fence about twelve inches and off the ground about twelve inches will keep sheep completely away from the fence. It’s also a good idea to spray vegetation killer under and on both sides.”

—Connie Wheeler

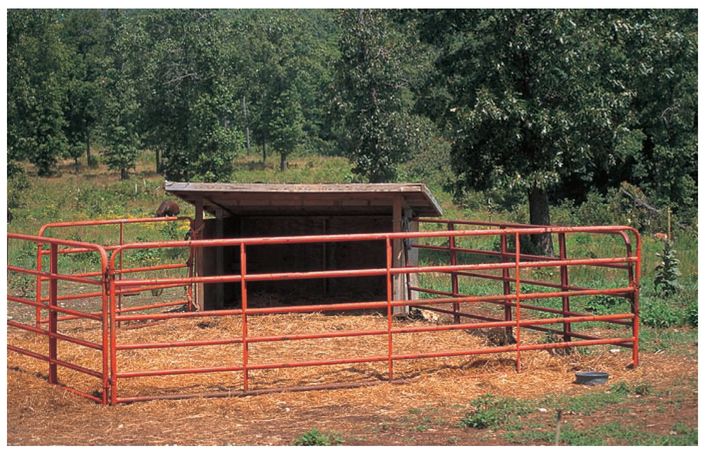

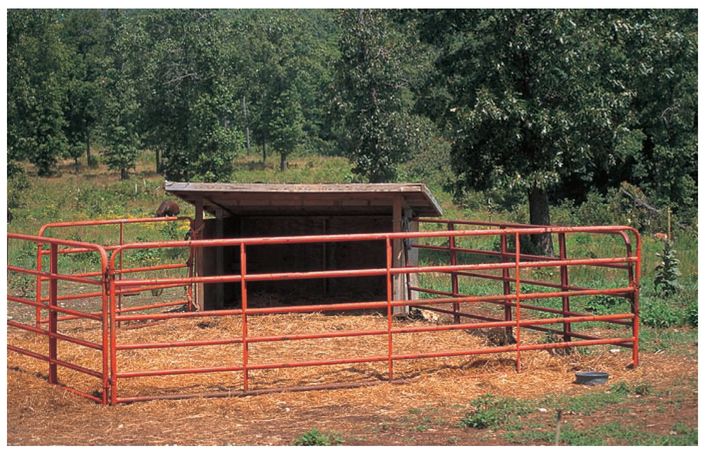

Designed to house miniature horses, this inexpensive, three-sided plywood structure with attached pipe gate enclosure provides adequate shelter for sheep.

SHELTERS

All a small flock (twenty-five or fewer sheep) really needs is access to simple shelters such as the one pictured here, erected with their open sides facing away from prevailing winter winds. They’re inexpensive and portable, useful for cleaning purposes, and they can be simply constructed by any reasonably adept home carpenter in a day. Be sure to allot enough space in your shelters for the number and type of sheep you own. Eight square feet is right for most breeds; twelve square feet is adequate for ewes with lambs. We call these structures mini-folds in honor of our Cheviots’ Scottish roots.

Whenever possible, place shelters on a southern slope with well-drained soil. Keep them close to your house to discourage predators and to make midnight-lambing time checks a little bit easier on a sleepy shepherd. Available space in an existing barn or shed can be used as well; just remember that sheep need to get outside at least part of the day. Indoor accommodations must be well ventilated but draft free.

PENS AND STALLS

You’ll need an indoor spot to erect your lambing jugs (small pens where ewes are confined with their newborn lambs for a few days postpartum; we’ll talk more about jug requirements in Chapter 6) and a quarantine, or “sick sheep,” stall. The areas needn’t be elaborate, just big enough for a single sheep or a ewe and her lambs to be comfy, dry, and out of drafts.

When choosing bedding, seek absorbency in a form unlikely to work its way deep into fleece and thereby spoil it. Don’t bed shelters, jugs, or quarantine stalls with wood shavings or saw dust. Shavings quickly imbed themselves in fleeces and ruin them, and the fine dust particles in sawdust are hard on sheep’s respiratory systems. Dust-free long-stem wheat straw is the bedding of choice, but other types of long-stem straws are all right, too. Avoid finely chopped straws of any kind. Other workable options include peanut hulls, ground corncobs, and the hay your sheep inevitably pull down and waste.

Can Ewe Safely Eat It?

There are few things more heart-breaking than losing animals because they ate poisonous plants that you should have grubbed out of their pasture. As shepherds, it’s our obligation to make pastures as safe as possible for our woolly friends. Unfortunately, it can be hard to know which plants and brush to remove. What’s perfectly safe for one livestock species to browse can dispatch another in record time, and flora varies widely from place to place, so contact your county agricultural agent to identify mystery plants your sheep are munching. Don’t assume they’re all safe to eat.

SHEEP FEEDING PRINCIPLES

Only a few classes of sheep routinely require concentrates: ewes during flushing, late-gestation and lactating ewes, hard-working rams, geriatric or underweight sheep, and an occasional lamb.

Concentrates must be sheep specific: whole or cracked grains, or commercial products labeled for sheep. Although the subject is complicated, suffice it to say sheep are easily poisoned by too much copper in their diets. Swine and poultry feeds are high in copper, as are some beef and dairy cattle rations. Even some goat mixes contain more copper than some breeds can handle. It pays to look for the words “sheep feed” on the label. For the same reason, you shouldn’t expose sheep to mineral licks or loose minerals designed for other species. Sheep require minerals, but in sheep-specific form.

No matter what some folks insist, sheep cannot safely digest spoiled or moldy feed, including musty hay. Consider mycotoxins—poisonous compounds produced by molds. They could be in that moldy feed. Moldy feed can trigger bloat, too. Measure feed, especially concentrates. Don’t feed a lot today and half that amount tomorrow. When group feeding concentrates, don’t let bossy gluttons hog it all. They can bloat or get acidosis and founder, while meeker flockmates literally starve. Sheep are creatures of habit. Try to feed them about the same time every day. They prefer to eat during daylight hours and in the company of other sheep. If you must switch feeds, do so gradually, over a ten- to fourteen-day period to allow sheep’s rumens to adjust.

HAY THERE!

Forage is the basis of most sheep diets. Consider hay, for example. Most hobby farmers have to buy it; you’re exceedingly lucky if you don’t. In some parts of the country, acquiring decent hay is an expensive proposition. It’s either not locally grown or not fit to feed. If you live in a place where quality hay is grown, you are at an advantage.

Small square bales usually work best for sheep; they’re easier to handle and store in a hobby-farm situation. Because you can dole out exactly what they need, the sheep waste less when fed from smaller bales. Large round bales are acceptable if they’ve been stored under cover and are free of mold. However, your sheep will pull hay down, then defecate and lie in it. You also can expect a lot of debris-contaminated fleece at shearing time. Nutrient-rich hay is green. Quality alfalfa is dark green; if it’s a strange lime green, it has been treated with propionic acid preservative. Authorities claim it’s safe, but if you’re not convinced, avoid it. Well-stored grass hay is light to medium green. The outsides of both legume and grass hays become bleached if exposed to light in storage, but inside the bales the hay should still be green.

If you see white dust, blemishes, or black spots, or if there is a musty smell, the hay was cut and stored before being fully dry. Even if you don’t spot actual mold, this hay shouldn’t be fed. Hay that’s pale to golden yellow inside and out wasn’t put up promptly; it got sun bleached in the field. It’s nutrition poor and apt to be dusty. Furthermore, it’s definitely not a good buy.

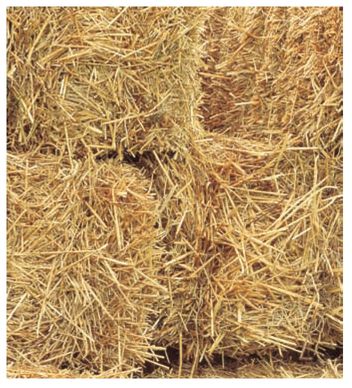

Hay bales of this size are a good choice for a hobby farm. Depending on the number of sheep you keep, larger sized bales sit longer in storage, gradually losing certain nutrients.

Golden yellow hay such as this offers up a nice snapshot, but it is likely to make poor feed for sheep. When purchasing bales, examine them closely for color, smell, texture, and moisture.

Quality hay is made from leafy plants mown just before blooming. It has thin, flexible stems that easily bend without breaking. Coarse, stemmy hay is low in nutrients and unpalatable, too. Leaves contain most of the plant’s protein; stems are mainly hard-to-digest, low-energy cellulose. As plants mature, they grow more stem than leaf. Stemmy hay made from older plants is no bargain, and hay containing mature blossoms and seed heads was mown well past its prime.

Refuse hay containing sticks, rocks, dried leaves, weeds, and insect or animal parts: your sheep can’t eat the sticks and rocks; the weeds may be toxic, and their seeds will infest your property; and baled insects and desiccated animals can cause serious disease. Don’t feed your animals uncured new crop hay, either. Age new hay fresh from the field for five to six weeks before feeding it. If you haven’t enough hay to last, buy enough dry hay to tide you over. Feeding uncured hay can easily trigger bloat. Old hay isn’t necessarily bad hay. Nutritious hay put up dry and carefully stored holds its nutrient content for several years. When its still green inside, old hay can be a bargain.

Whenever possible, buy tested hay from a reputable hay dealer. It takes a lot of guesswork out of the equation. Be extra cautious if you buy hay at auction. Some sellers place their best bales on the outside, where buyers can see them, and tuck junky hay deep inside the stack. Inspect the hay you plan to buy. Agree to pay for a couple of bales you can open. See what they look like inside. If the hay doesn’t pass muster, you aren’t obligated to buy the rest.

If you can have your hay delivered and neatly stacked in the barn, do it. Unless you’re young and energetic, and have a great back and knees, it’s extra money well spent. Buy only the amount of hay you can store under cover. Stack it on pallets to get it off the floor; if you don’t, the bottom layer will rot. Don’t let barn cats defecate or have kittens on it; cats are primary carriers of toxoplasmosis. Finally, to minimize waste and prevent disease, use those feeders. Never feed hay off the ground.

ALL THE AMENITIES

Your sheep need something to eat out of. There are countless styles of hay and grain feeders to choose from. Large, sturdy-plastic grain feed pans are tough, portable, and easily cleaned. Wallmounted steel rod racks work well for hay. A great portable hay feeder for just a few sheep is a horse-style nylon hay bag. You’ll find durable multisheep feeders at farm and feed stores, or you can order them from sheep supply catalogs.

Another option is to build your own feeders. If you request item #900000 when placing an order from the Premier sheep supply catalog, the company will send free plans for its walk-through and drive-by flock feeders. The walk-through plan is especially nice if your flock includes a testy ram.

Sheep shouldn’t eat out of standard big-bale feeders. When they bury their heads in the hay to choose the choice morsels, they imbed a lot of nasty debris in their fleeces. They may also rub off patches of their fleeces when they lean against pipe rails while eating.

•Don’t feed hay off the ground. Once one sheep defecates or urinates on it (and one will) none of the others will eat it. Eating off the same stretch of worm-egg-infested earth encourages worm infestation, too.

●Mount feeders reasonably close to the ground so hay chaff doesn’t drift into faces and fleeces while sheep are eating.

●Locate feeders where you can place hay or grain in them rather than flinging it. Sheep raise their heads when it’s least expected: voilà, a face full of hay or grain.

Two of our girls, Ewephemia and Ewelanda, munch supper from a secondhand cattle mineral lick pan. Feed stores carry myriad styles of livestock feeding and watering troughs. Alternatively, you can be creative with homemade or used versions.

Advice from the Farm

Sheep Feeding Tips and Tricks

Our panel of sheep experts discuss feeds and feeding.

Feeding Geriatric Sheep

“After breeding time, we take our older girls and pen them together in a separate area from our younger ewes. We call it our geriatric pen. These old ewes get about one-half pound each per day of Equine Senior. It has made an amazing difference in their weight, activity, and the babies they produce. For a treat, they love bread.”

—Lyn Brown

Selecting Feed

“My four kids raised the three main species of farm animals for 4-H and Future Farmers of America (FFA) market shows, with numerous grand champions along the way. We always fed the feed that the local feed mill produced for that particular species and our specific location . It worked well for us. The feed contained the trace minerals our area needed and the feed composition percentages the species needed.”

—Lynn Wilkins

GUARDING YOUR SHEEP

According to the National Agricultural Statistics Service, predators (coyotes, dogs, bears, cougars, bobcats, foxes, and eagles) killed nearly 5 percent of America’s sheep population in 1987. This represented a loss of $83 million to the farmers and ranchers who kept them. By 1999, predation losses were down to $16.5 million. The reason? A growing legion of sheep producers have been turning to flock guardians—dogs, donkeys, and llamas—to protect their flocks.

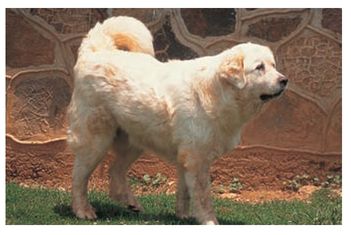

Canine flock guardians are not herding dogs or pets; they’re specialists bred to guard livestock—and they do it well. Originating in Europe and Asia, guardian breeds include the Great Pyrenees (from France), the Yugoslavian Sharplaninetz, the Hungarian Komondor and Kuvasz, the Turkish Akbash and Anatolian Shepherd, and the Italian Maremma Sheep Dog. These dogs are raised with and bond with sheep, so they simply remain with their “flockmates” at pasture. About three-fourths of these dogs become good guardians by actively repelling small predators and by alerting their owners when the flock is threatened. However, some simply don’t like sheep, others wander, and still others want to stay by the house and be pets.

Guardian donkeys live longer than do guardian dogs, they’re inexpensive to buy and maintain, and they require no special training. Like llamas, donkeys instinctively dislike the canine clan and protect their herds (be they sheep, goats, poultry, or other donkeys) from stray dogs, coyotes, and even wolves. A donkey in attack mode can gallop and stomp at the same time. Needless to say, a new guardian donkey must be carefully introduced to family dogs—who will quickly learn to give the newcomer a wide berth! Like dogs, some donkeys dislike sheep and will hang around the barn seeking human contact instead of minding the flock. However, people who like donkeys swear by these long-eared guardians.

Llamas may be the best bet for hobby flock guardians. Llamas bond with their woolly charges extremely well, eat the same feed, and require most of the same vaccinations as sheep. Llamas, especially females with cria (suckling offspring) and castrated males, instinctively guard their herdmates, even when their “herd” consists of sheep. Guard llamas shriek at, charge, and sometimes stomp marauders. Few small predators (such as dogs and coyotes) willingly tackle the same angry guard llama twice. (See the Appendix for more information.)

This handsome Great Pyrenees guards the farm of Dick Harward and Barb Zebbs. Great Pyrenees are the North American livestock guardian dogs of choice. Other favorites include the Akbash, Anatolian Shepherd, and the Tibetan Mastiff.