CHAPTER SEVEN

Fleece: Shearing, Selling, Spinning

Unless your sheep are hair sheep, they absolutely must be shorn. This is necessary not just to harvest fleece, although that’s a valid reason; it’s the healthy and humane thing to do for several reasons. For one thing, most unshorn sheep keep growing wool. For another, rain-logged fleece pulls on tender skin, causing skin separation, pain, and sores. Masses of filthy fleece invite fly-strike. Megawoolly, unshorn sheep are prone to heat stroke. Pregnant ewes may lie down, roll onto their backs, get stuck, and die.

Whether made from the fine wool of a Merino or the felt from scraps obtained during your first attempt at shearing, you can make a wide variety of garments. You can also pick up some hefty bucks from others who wish to use your fleece, such as handspinners.

THE FLEECE COMES OFF

That the wool has to come off is a given, but shearing is a stressful time for sheep (and shepherd, too). Make the process as neat and painless as you possibly can. First, learn which time of the year is best for shearing your sheep. Next, decide whether to hire a professional shearer or to learn to do the job yourself.

TIME IT RIGHT

Although mild-climate wool producers sometimes opt for winter shearing, sheep are traditionally shorn from March through May. Some breeds are shorn twice a year, in spring and again in early fall. Your shearing schedule will depend on a number of factors, including the type of sheep you have and your locale.

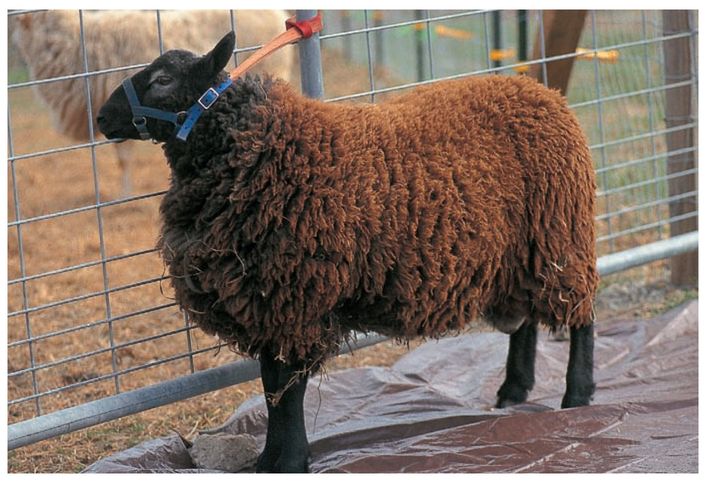

Before shearing: Baasha models a year’s growth of sun-bleached fleece.

Many shepherds shear their ewes before lambing. Otherwise, new lambs seeking their mothers’ teats sometimes find and suck wool tags instead, missing out on vital early meals of colostrum.

Shorn ewes take shelter when it’s cold, whereas sheep with warm, heavy wool may stay outdoors where their tender, newborn lambs are apt to freeze. The downside to pre-lamb shearing is that late-term ewes must be handled more carefully than other sheep. It’s wise to have them shorn well before lambing.

Did Ewe Know?

Wild sheep have hair rather than fleece; they do grow a woolly winter undercoat, which they shed each spring. However, a 6,000-year-old figure of a woolly sheep was unearthed at an archaeological dig in Sarab, Iran, proving that wool sheep had been developed by that early era. By the ninth century BC, the Greek poet Homer praised the whiteness and quality of wool produced in Thessalia, Arcadia, and Ithaca.

Unless you can temporarily place them in a warm barn or blanket them, don’t shear sheep until the last winter storms have passed. It takes most sheep six weeks to grow an insulating layer of wool, and they’re especially vulnerable for several days post shearing. By the same token, in steamy southern locales, you should shear before warm weather sets in. Heavily fleeced sheep, especially dark-colored individuals, sizzle under a sultry summer sun.

THE PROFESSIONAL SHEARER

If you can hire a competent shearer, you’re wise to do so. The job requires know-how, a strong back, and specialized tools. Shearers are in very short supply, and good ones are scarcer still. If you can hire a shearer, choose one with a sterling reputation. The shearer should handle sheep humanely and remove their fleeces in readily marketable condition. To locate shearers, ask other shepherds for recommendations, scout for business cards and flyers on the bulletin boards of feed stores and large-animal veterinary practices, call your county agricultural agent or state vet school, and peruse online livestock directories.

After shearing: The beautiful Baasha appears much darker with her sleek new ‘do.

Skills and Fees

Ask for and check shearers’ references, and explain your expectations up front. Shearers are paid by the head, so they want to work quickly and be on their way; some aren’t willing to slow down to bow to humane demands. If that’s the case, look elsewhere or learn to shear your own sheep.

The epidermal layer of sheep skin is thin and tender, so even the best shearers sometimes nick, scrape, and ding your sheep. But multiple superficial wounds, deep cuts, and teat and penis injuries are unacceptable, as is hauling sheep around by their wool. A fleece should be removed in a single piece. Reshearing a given area results in short bits called second cuts. They drastically reduce market value and are the mark of a careless or inexperienced shearer.

Shearers charge by the head, usually in the two- to fifteen-dollar range. They figure fees based on how far they must travel to your farm, the number of sheep they’ll process, and the type of wool they’ll be handling. If you have a small flock, be willing to pay premium per capita, mileage, or setup fees to obtain quality service. It’s not cost effective for professional shearers to drive many miles to shear a flock of fifty head or fewer.

Did Ewe Know?

Today’s method of shearing sheep—the Bowen Technique—was pioneered by New Zealander Godfrey Bowen in the 1940s. His brother, Ivan Bowen, won the first International Golden Shears title in 1960, along with four more world championships. At eighty-four, Ivan still competes in Golden Shears veteran competitions, shearing a sheep in about sixty seconds. He does a hundred push-ups each morning to stay in shape.

Better Fleece

Producing Better Fleeces

Whether or not you jacket your sheep, there are ways to produce better fleeces.

• Clean up your pastures. Weeds, burdock burrs, thistle fluff, and seed heads all work deeply into fleece.

• Avoid hay and straw put up with polypropylene strings. Short bits of twine sucked into the baler end up tangled in fleeces, and it’s the hardest contaminant to remove. Keep an eye out for stray plastic feed-sack fibers, too.

• Don’t use feeders that allow sheep to bury their heads in hay. Standard big-bale feeders are especially poor choices.

• Don’t toss hay at feeders when there are sheep in the path. When feeding concentrates, try to avoid pouring grain onto the heads of sheep jostling for position at the feeder.

• Choose contaminant-free, long-stemmed straw for bedding; reject straw full of weeds, seeds and chaff. Waste hay will work if it’s free of dust, mold, and fleece contaminants. Don’t use sawdust or wood shavings unless they’re tipped by straw or hay.

• If you use a marking harness on your ram or you spray paint numbers on ewes and lambs for identification purposes, choose chalk, crayons, or paint that easily scours out of fleeces.

• Never allow your sheep to be shorn when they’re wet. Damp fleece yellows and molds.

• Keep your sheep dewormed and free of sheep keds, lice, and other skin irritants.

• Follow a well-balanced feeding program. Well-fed sheep grow twice as much wool as scrawny, sickly sheep.

• Vaccinate for diseases prevalent in your locale. Sick and otherwise stressed sheep suffer wool break when their fleece growth is temporarily interrupted and then resumes growing, leaving a weak spot in each wool fiber.

• Choose a breed that produces the type of wool you want to market. If you’re not sure, scope out the resources at the end of this chapter or join a fiber arts e-group.

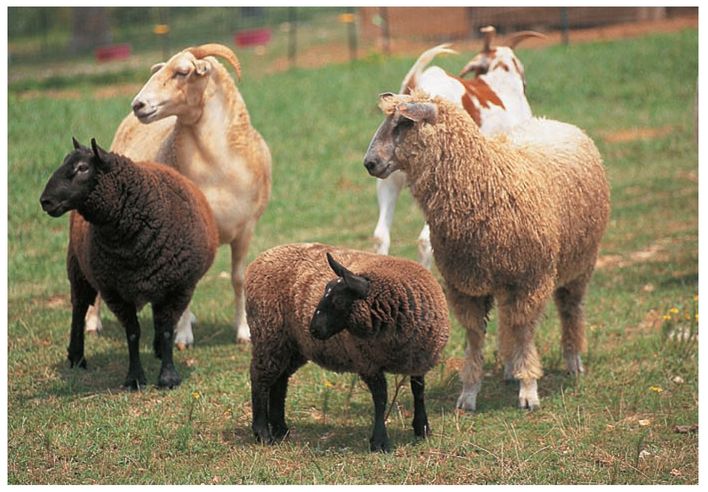

• Consider black sheep. Most handspinners prefer black (which actually ranges from ebony to shades of pale gray) or uniquely colored fleeces such as those grown by Icelandics, Shetlands, and Navajo-Churros. Quality white fleece sells too, but colors are all the rage.

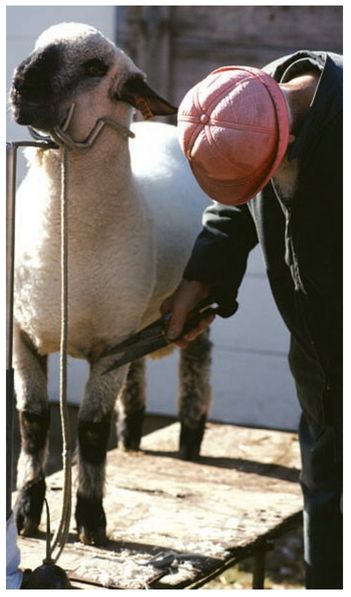

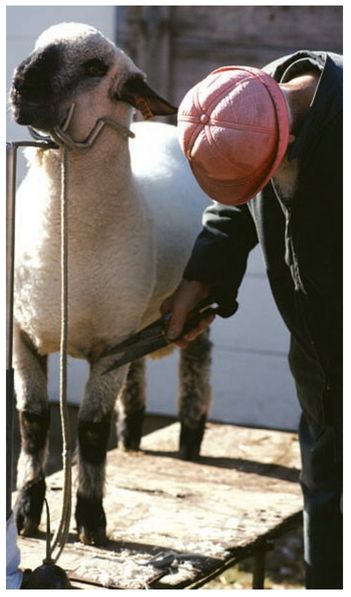

Positioning sheep on a grooming stand, as shown here, is helpful for new hobby farmers who may find professionals’ moves cumbersome. The elevation allows the shearer to move around the animal for a precise cut rather than awkwardly bending over a fidgeting sheep.

Another option is to check with other small flock keepers in your locale and arrange everyone’s shearing for the same day or weekend. If you do, ask the shearer to visit each farm; don’t gather sheep at a central location. Commingling sheep easily spreads disease from flock to flock.

In days past, many shearers accepted shorn fleece in lieu of fees. Today’s commercial wool prices are too low to make this economically feasible, although some will charge less if they take your wool.

Shearing Prep

Once you’ve scheduled the services of a recommended shearer, start preparing for his or her arrival. The night before the visit, pen your sheep in a clean, dry, roomy section of a barn or shed. Sheep can’t be shorn if they’re wet—and that includes dew or frost.

Sheep shouldn’t eat for eight to twelve hours before shearing. The positions the shearer places them in are fairly comfortable for sheep as long as their stomachs aren’t packed. Uncomfortable sheep are likely to struggle, and struggling sheep often get nicked.

Provide a clean, level shearing surface. Have it in place before the shearer is scheduled to arrive. Two possibilities are a clean tarp or two sheets of plywood with the space between them sealed with duct tape. Shake the tarp or sweep the wooden surface between sheep. The shearing floor should be situated in a well-lit, well-ventilated, covered area. Have heavy-duty extension cords on hand if your shearer needs them (ask when you make your appointment); flimsy household cords won’t do.

Arrange for additional help if you need it (and you probably will). The shearer’s basic fee doesn’t include snagging reluctant sheep from the flock or hauling them to a pen when finished. Stock up on season-appropriate hot or cold drinks for your shearer and helpers; wrestling sheep is thirsty work. If shearing overlaps lunch or supper time, provide sandwiches but not a heavy meal.

Abram is haltered and ready for shearing. A drop cloth or plastic tarp such as this protects shorn fleece from contaminants. It should be swept or shaken clean between sheep.

Just Between Ewe and Me

Whether or not you jacket your sheep, there are ways to produce better fleeces.

• Wear old shoes. Sooner or later, someone will pee on your foot.

• Don’t wear shorts. Scrabbling sheep hooves hurt—a lot.

• If you thing the gentlest sheep will be the easiest to shear, you are mistaken.

• Newbies don’t peel off nice, neat one-piece fleeces—ever.

• After the sheep are shorn, you can touch up your motley job with horse clippers. But clean them between each sheep!

• Mistakes grow out, and sheep forgive you—no matter how funny they look.

Pen your nonworking dogs, and keep herding dogs away from the shearing floor. Dogs worry many sheep, causing undue stress and fidgeting. Stay with your flock until the job is finished. Make certain it’s done to your satisfaction.

Keep antiseptic at the ready to treat nicks and dings. The shearer shouldn’t have to wait while you fetch it. If you trim hooves and deworm on shearing day, do it after the sheep are shorn. Don’t expect the shearer to hold each sheep while you trim or treat it.

Advise the shearer of special needs before shearing begins. Elderly, chronically lame, and recently ill sheep require gentler handling, and a lone wether in a flock of ewes could have his penis zipped off if a speedy shearer doesn’t know it’s there. If it’s cold and you haven’t proper shelter for shorn sheep, ask the shearer to use winter combs that leave a short layer of fleece on your animals. When the shearing is done, pay up. Don’t expect the shearer to mail you a bill.

A strange dog’s approach puts our wee flock on alert; even the lambs are wary. Since sheep remain constantly aware of their surroundings, make sure your shearing area is secured from dogs and other animals whose presence may stress your sheep.

WHEN THE SHEARER IS YOU

Amateurs can certainly shear their own sheep, but don’t expect a professional-looking job the first few times. Invest in quality tools. Determine which sheering position—sitting or standing—will work for you. Your back and your sheep will be grateful you did.

Tools: Hand Shears or Handheld Electric Shearing Machines

When you have only a few sheep to shear, or if money is a concern, traditional hand shears will do the trick. A high-quality, triple-ground shear with 6.5-inch blades costs about twenty-five dollars, and a second set of twenty-dollar minishears makes touchups a snap. Add a six-dollar sharpener to refresh their edges between professional grindings, and you’re in business!

Keep your shears sharp. Hold them parallel to the animal’s body. While you’re learning, work slowly and cautiously, or you’re likely to cut your sheep. As you gain experience, you can work considerably faster.

If you’re short on time, have a lot of sheep, or cost isn’t terribly important, invest in good electric shears. Shears are not horse or dog clippers; they are heavy-duty machines equipped with heads specifically designed to shear sheep. Oster, Andis/Heiniger, Lister, and Premier build quality shearing machines. You’ll find a comparison of handheld electric shears in Premier’s free sheep and goat supply catalog (see Appendix).

Plan to spend 250 to 350 dollars for electric shears and roughly forty to fifty dollars for each comb and cutter set.

You’ll need twice as many cutters (extras run about five dollars each), as they dull much faster than combs. Pros shear up to twenty sheep per comb and ten per cutter; novices should allow two cutters and a comb for each pair of sheep. Combs and cutters can be professionally resharpened about ten times; don’t try to resharpen them yourself! You’ll also need clipper oil; choose a clear product to avoid staining fleece.

While in use, cutters with clipper oil at three- to five-minute intervals. Clean and coat blades with clipper oil within an hour after you finish shearing; store them in plastic clipper-blade boxes. Stow everything in a sturdy case or padded bag. Take care of your shearing gear to make it last.

Taking a Seat or Standing

Professional shearers follow a set shearing protocol, swiftly setting and swiveling sheep in a series of positions whereby they’re immobilized, and marketable fleece is zipped off in a single piece. Hobby farmers can learn this set of moves or shear their sheep while standing. Weekend shearers of limited strength and battered back will likely prefer the latter ploy.

A shearing stand makes the job a whole lot easier. A goat-milking platform or the sort of stand designed for beautifying show lambs works very well. If you don’t have one, not to fret; you can shear sheep standing on the ground.

Secure the sheep’s head. Show sheep stands are fitted with a cradle apparatus that does just that; a fencemounted version is available from Premier. If you have neither, use a halter and lead to tie the sheep to a sturdy fence. Use a slip knot in case it gets tangled and needs to be set free fast.

John shears Abram the old-fashioned way, using traditional hand shears. This is often the best method for small flock owners (though Abram isn’t certain he thinks it’s a good idea).

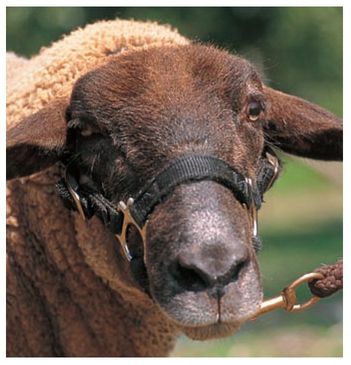

Dodger sports a sheep halter and lead—just the right gear for shearing time. Hobby shepherds have many varieties of halters to choose from, including popular show halters such as this, one-size-fits-all plastic rope halters that cost under three dollars each, and flat nylon halters designed for miniature horse foals and yearlings.

Be patient. Most sheep aren’t thrilled with this situation. Start at her head and work carefully to remove desirable fleece in a single piece. When it’s off, shear her face, lower legs, and as much belly wool as you can, then set her on her butt to finish the rest. Take long, bold strokes with electric shears, and keep the comb flat against your sheep’s skin. If the comb rises, don’t make a second sweep—at least not until the fleece has been removed.

Don’t expect instant success. Your first shearing will probably ruin the fleece for commercial purposes and embarrass both you and your sheep. But take heart; you can use the wool for home felting projects or quilt batts, and the more you shear your sheep, the better you’ll get.

Whether a professional shears your sheep or you do it yourself, you must take proper care of the shorn fleece if you plan to sell it. This includes caring for the fleece while it’s on the sheep as well as after it’s removed. Some ingenious ideas have been developed for such purposes.

SHEEP CHIC

In 2001, Australian Wool Innovation Ltd. commissioned a study to determine the economics of jacketing sheep. Twelve hundred Australian sheep in six flocks (including a control group) took part in the study. Its findings: covers significantly improved wool yield, reduced fleece contamination, and drastically reduced fleece rot and fly-strike. They didn’t affect fleece weight, micron count, or staple length and strength. The paper recommends that sheep coats be constructed of tightly woven ripstop nylon treated for UV resistance, with expandable fronts, rump coverings, and roomy leg straps. The experiment was a rousing success.

Did Ewe Know?

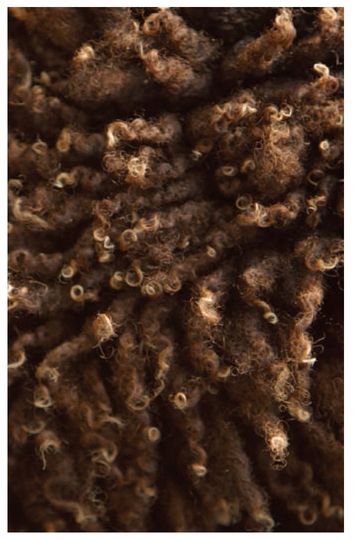

A single, magnified wool fiber resembles a stack of flowerpots piled one inside another, all facing outward from the base. Stroked through fingertips from base to tip, its shaft feels smooth; tip to base—stickery. This scaly outer covering is called the cuticle; it causes fibers to interlock with one another. Inside each fiber, a cablelike cortex imparts strength. A wool fiber is so springy and elastic that it can be bent more than 30,000 times without harm. Stretched, considerable crimp allows it to spring back to shape.

Most American small-scale producers of handspinners’ fleeces jacket their sheep. Besides keeping fleeces clean, covers keep sheep warmer after shearing and cooler in the hot summer months (white jackets on colored sheep are especially useful). Their failings: shepherds spend considerable time and effort making, laundering, repairing, changing, and making certain sheep coats fit. Some felting of fleece may occur in some breeds, especially along the spine and around necklines. Considering that coated fleece routinely sells for considerably more than the price of unjacketed fleeces, most shepherds consider it a pretty fair trade-off.

Whether light or dark in color, wool samples such as this are evaluated according to set guidelines for grade, class, and quality.

It’s fairly easy to sew your own sheep coats, but you can buy them, too. You’ll need several sizes per sheep to allow for fleece growth. However, the size one sheep outgrows may neatly fit a flockmate—at least for a while. Ready-made sheep coats run ten to eighteen dollars each, depending on size.

You have some choice in materials. If coats aren’t crafted of breathable fabric, the wool they cover can mildew or mold. Uncoated nylon and woven plastic fabrics work well, but canvas is usually a poor choice, especially in damp climates.

Most commercial models slip over a sheep’s head, then its legs are threaded through the leg straps. It’s fairly easy to jacket sheep that are accustomed to wearing covers. Things can get terribly exciting, however, the first time your flock gets dressed.

SELLING THE FLEECE

Nowadays it usually costs more to have sheep shorn than their wool is worth. Yet a growing legion of small-scale sheep keepers—hobby-farm shepherds, if you will—show a tidy profit (or at least pay for their flocks’ annual upkeeps) by producing quality fleece for handspinners. There are other markets and uses for the fleece as well.

THE LINGO

To deal in wool, you must learn the lingo. First, familiarize yourself with terms that refer to the fiber itself. The value of handspinners’ fleece is determined by its grade (the fineness of the fiber), class (its staple length, meaning the length of the fiber), and quality (its freedom from contaminants and the character of the fiber).

Advice from the Farm

Sheep Coats and Wool Selection

Our sheep experts talk about sheep coats and wool selection.

Nylon Coats

“I’ve seen sheep coats made of canvas and have used them, as well as coats made out of lawn furniture fabric, but I like nylon ones best—they’re light, so the wool doesn’t felt underneath; they’re puffy, so the wool doesn’t press; and they shed water, so the wool doesn’t rot.

“The ones I’m using are fabulous! I get them from

moharefarms.com. I’ve never seen my coated sheep pant any more than non-coated sheep, and if I stick my hand under their coats, the sheep aren’t sweaty. I can’t recommend them highly enough. The only drawback is that they do tear easily. One good snag against a fence post splinter and RIIIIIPPPPP, a nice big tear. That’s why I get sheep coat patches from Melissa Gray (grayjoe@charter.net); then they last me for years.”

—Laurie Andreacci

High-Value Wool

“I did a lot of looking via the Internet and discovered that there is an up-and-coming market for fiber animals to meet the needs of the resurgence of spinning and weaving. There is a demand for both the animals and the fiber.

“Based on the wool sale results at the 2002 Black Sheep Festival in Eugene, Oregon, I narrowed my search down to breeds who have a high-value wool. My next criterion was breeds with lambs selling for a minimum of two hundred dollars a head for breeding purposes. I wanted breeds that would average one hundred dollars a head on the lambs between the ones who went for breeding and the ones sold for meat. My third criterion, since there was going to be a percentage of meat animals raised, was that the breed had to have some size to it. My last criterion was a breed that shorn a minimum of 10 pounds of wool a year.”

—Lynn Wilkins

These wool samples are (from left to right) Rambouillet, Border Leicester, Keyrrey-Shee, and Scottish Blackface sheep.

Fiber diameter is measured in microns (a micron is 1/1,000 of a millimeter, and about 1/25,000 of an inch; this is called the Micron System) or numerical count (also called the English or Bradford Spinning Count System). Numerical count refers to the number of 560-yard hanks of wool that could be spun from 1 pound of clean wool. For example, Cheviots grade 27 to 33 microns and 46s to 56s (46 to 56 hanks of yarn).

The American Blood Count System is a largely obsolete third way to measure fiber thickness. In it, wool is compared to Merino fleece, which is considered fine wool (2.5-inch staple with lots of teensy crimps per inch). The seven accepted grades are: 1/2 blood, 3/8 blood, 1/4 blood, low 1/4 blood, common, and braid.

Staple length is the length of a lock (staple) of greasy (unwashed) wool measured in inches in the United States and in millimeters abroad. Staple strength is the force needed to break a staple measured in newtons per kilotex. Crimp is measured in crimps per inch in the United States and per centimeter elsewhere. Fine wool measures more crimps per inch than do coarser wools. Yarn spun from closely crimped fiber is more elastic than yarn spun from uncrimped wool.

Luster (lustre in Great Britain) equals sheen. Coarser wools from breeds such as the Leicester Longwool, Teeswater, and Wensleydale are more lustrous than wool from fine-wool and down breeds. Sheep coats keep junk such as dirt, burrs, grain, hay, and bedding out of the best parts of a fleece. Although coats don’t completely cover a sheep, the exposed wool is on parts skirted (cut) off of handspinners’ fleeces anyway. Yield is how much fleece is left after skirting. Wise producers skirt generously, removing all low-grade and contaminated wool. Skirted material isn’t waste; it can be packaged separately and sold at a lower price to felt makers. Grease wool is unwashed fleece, just as it comes off the sheep. Some breeds are greasier than others; Merinos and Rambouillet produce heavy-grease wool. After scouring (washing), a fleece weighs considerably less than when it was “in the grease” (unwashed).

It’s time for shearing! The quality of fleece—and the price it fetches at market—depends on shepherds’ preventive care and maintenance. (See Producing Better Fleeces sidebar.)

HANDSPINNING

Handspinning as a craft has taken the country by storm. If you’re interested in producing handspinners’ fleeces, there’s a ready market for a quality product. The best way to get a feel for handspinning is to try it yourself. Start with simple drop-spindle spinning and if you like it, take some classes and buy a spinning wheel. Due to the burgeoning interest in handspinning, classes are increasingly easy to find. You may want to consider buying a copy of Paula Simmons’ Turning Wool Into a Cottage Industry—it’s an absolute must-read.

DROP-SPINDLE SPINNING

As many as 10,000 years ago, even before they domesticated sheep, New Stone Age humans gathered bits of shed wool and spun them into yarn. Archaeologists working Neolithic and Bronze Age digs throughout the world uncover stone whorls from ancient drop spindles.

All wool was processed with drop spindles until the spinning wheel was invented during the Middle Ages. But the drop spindle never fell out of vogue. It’s inexpensive, portable, and easy to use. Drop-spindle spinning is still the mode of choice in many third-world countries, and it’s enjoying a revival right here at home, too.