Four centuries of Roman rule in Britain came to an end in the year ad 410. This date has become one of the turning-points of history, the supposed hinge between Latin civilization and the Dark Ages. In retrospect, as recalled in the writings of Gildas and Bede many years later, it represented the moment when the light of civilization went out. One moment Britain seemed to be a united, sunlit land of villas, well-maintained roads and orderly towns, and the next it was plunged into the feral chaos of roving war-bands, hill-forts and whole cities in flames. The unity of Britannia is supposed to have fallen apart soon after the Roman legions departed, when civic governance was replaced by anarchy, invasion and war. To the Saxons watching from the wings, it seemed that they had only to kick the door down and the land would be theirs for the taking.

In reality it probably wasn’t much like that. The departure of the Roman legions was not a sudden event (and a lot of individual legionaries probably did not depart). The rot started at least as early as 367, when Roman Britannia was brought close to collapse by ‘barbarian’ invasions from the north and south. In the chaos, Britain’s senior general (Dux Britanniacum) was taken prisoner, and his deputy killed. Then, in 383, many troops departed when the new general, a Spaniard called Magnus Maximus, made a bid for the Empire and took his British legions with him to Gaul. Maximus was killed the following year, but his men did not return to Britain.

The final denouement came in 406 when, according to the Greek historian Zosimus, the army in Britain set up first one rival emperor and then another. The eventual winner was Constantine III, who, like Maximus, was obliged to denude Britain of its garrisons and standing army in order to deal with the even more serious situation in Gaul, over-run by Vandals, Burgundians and Franks from central Europe. By 410, it seems, the legions had already left. All that happened in that year was that the emperor was obliged to send a circular to the cities of Britain inviting them to take responsibility for their own defence. Rome could no longer spare the men.

In practice, Britain had already taken steps to protect itself long before the climactic date of 410. However they were being constantly frustrated by emergencies across the Channel. In the circumstances, ‘independence’ from Rome need not necessarily have been a disaster, since for many years Britain had been providing troops for the Empire rather than the other way round. The real problem seems to have been the failure to establish a central authority in place of the Roman governor. Britain needed a man on the spot to take charge of the army and navy, and co-ordinate the national defence: in other words, its own emperor or dictator. But without Rome, the tribes of Britain could not agree on a successor. Britain was not a unified country but a collection of tribal territories. The tribes seem to have maintained their identity throughout the centuries of Roman domination, and no doubt also their traditional rivalries and alliances. The position in 410 was as if today’s central government had disappeared, leaving only the boroughs and county councils, each with their own interests and agenda. Who was to organize and command a national army, maintain the garrisons of Hadrian’s Wall and guard the great military forts of the Saxon Shore?

In the decades after 410 it seems that such a leader did emerge. Later generations called him Vortigern, the tyrannus superbus or ‘proud tyrant’. But Vortigern’s power was probably much more restricted than that of the Roman governors, who had three legions to maintain order. He was more of a tribal over-king, whose authority was strictly personal, and so limited. He would have had enough trouble maintaining his authority among the British without fighting invading Picts and Saxons as well. Britain’s defences, like those of the greater Roman Empire, were based on keeping the enemy out. But the enemy was already within and Vortigern urgently needed men to fight them. And so, far from keeping the external Saxons out, he invited them in as foederati, that is, federal troops or, as we would call them now, mercenaries.

Who were the Saxons? They were part of the people the Roman historian had described three centuries earlier as Germans. Their homeland was in what is now northern Germany and Denmark. Tradition preserved in the later writings of Bede divides them into three tribal groups. One was the Jutes from Jutland, who are said to have settled in Kent and, later, in the Isle of Wight and parts of Hampshire (the New Forest was known in Bede’s day as ‘the Jutish nation’). The Saxons in the middle colonized Essex, Sussex and most of Wessex; while the third tribe, the Angles, helped themselves to the rest of East Anglia, the Midlands and the land north of the Humber, soon to be known as Northumbria.

Whether the three tribes, all from broadly the same area and speaking dialects of the same language, were really as distinct as Bede makes them out to be is debatable. There is nothing particular to distinguish them archaeologically, apart from a greater sophistication in grave-goods on the part of the Jutes – and that is more likely to be due to trade between Kent and Gaul than any actual cultural superiority. Recent DNA evidence from buried bones suggests that genetically they were one and the same people. They were all effectively the English. And, of course, being English in the fifth century meant being pagan, barn-living, slave-driving and violent.

The native lowland British, by contrast, tended to live in towns, many of which now sheltered behind high walls. The better-off had villas in the country with under-floor heating and hot baths. Most of the British were Christians. They went to church and paid for goods with coins. They had a road system better than anything that people would see again until the eighteenth century. The country was fertile and well-watered with a prosperous agriculture, numerous wood-based industries, including iron and tin-smelting, glassworks and potteries. The population was around three to four million. What they may not have had was the cultural and political unity to maintain law and order once the Empire came under severe pressure. Like everywhere else in the Empire, this was a fragile civilization depending on central authority from Rome. To someone living in the middle of the fifth century and watching it all collapse about them it must have seemed like the end of the world. Quite how Roman Britain fell apart is not clear, but it certainly happened violently. The archaeological record indicates that for a long while after the mid-fifth century there was no currency, no native glassware, no hot baths and no literate clergy to record what was happening. All we have to remember this darkest of Dark Ages are words written down in later centuries from tales remembered perhaps in song and verse. They may not be accurate or even necessarily true but they are all we have.

Vortigern, so the story goes, invited three ship’s companies of Saxons to serve him as federal soldiers (foederati) in his wars against the northern tribes. Their leaders were the brothers Hengest and Horsa. They were given lands in the east, and served Vortigern with distinction in the northern wars. Nonetheless Hengest and Horsa’s real interest lay in founding an independent kingdom. They sent news to their compatriots on the continental mainland that Britain was fertile and its native people cowardly. Swollen by immigrants, the Saxons became a formidable military force. When Vortigern ran out of money and rations, they mutinied. Gildas says they rampaged from coast to coast. Which coast that was is unclear. He may have meant the coast of Kent.

The archaeological record tells a different story. The traditional year of Hengest’s arrival at Ypinesfleot (Ebbsfleet) in Kent is 449. But Germans had settled in Britain long before that. Germanic objects, including brooches, pottery and the distinctive square belt-buckles worn by Germans in Roman military service, have been found over a wide area of south-eastern Britain in the first half of fifth century, from the Channel to the Humber. Hence soldiers and settlers of Saxon origin and with Saxon customs were already living in Britain long before the arrival of Hengest’s modest fleet of ‘three keels’ (i.e. ships). Hengest is the name around which stories later clustered, but he may be a mythical figure. His name means ‘stallion’ (Horsa means ‘mare’) and possibly has its origin in a Germanic horse-god. Or possibly it was a nickname, taken perhaps from the stallion on an unnamed war-lord’s banner. The myth of founding twin brothers is also reminiscent of Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome.

But at least the circumstances of Hengest’s rebellion are plausible. So are the battles associated with him and recorded, along with their supposed dates, in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The first of these was fought between the armies of ‘Hengest’ and Vortigern, at Agaelesthrep or Aegaelesford (Aegle’s Ford) in 455. It was remembered for two reasons, first, because Horsa was killed in the battle, and secondly because, as a result of it, ‘Hengest succeeded to the kingdom’. This battle is also mentioned in an independent source, the Historia Brittonum, a collection of ancient documents preserved by the Welsh monk Nennius in the early ninth century.1 In this version it was fought at ‘the ford called Episford in their language, Rhyd yr afael in ours, and there fell Horsa and also Vortigern’s son Cateyrn (Catigern)’.

The agreement of two separate sources makes it probable that this was a real event. Agaelesthrep has been plausibly identified with Aylesford, just north of Maidstone, one of the few fordable points on the Medway. Horsa, according to Bede, was buried ‘in east Kent where his monument still stands’2 – though unfortunately we don’t know where. Tradition places Catigern’s burial in the Neolithic chambered tomb called Kit’s Coty, a short way north-east of Aylesbury. This may be folklore but they do say the place is haunted.

Two years later ‘Hengest’, this time accompanied by his son Aesc (or Oesc, and pronounced ‘ash’), fought against the Britons at Crecganford. This is modern Crayford, many miles west of the Medway in what are now the suburbs of London. Again there is confirmation in Nennius’s chronicle, which mentions a battle fought on the Darenth, into which the River Cray flows just north of the town. Crayford happens to be crossed at this point by the Roman road called Casing Street, linking Rochester and London. Perhaps the most likely scenario for this battle, therefore, is that the Britons were barring a Saxon march on London by massing at the river crossing. The battle was a disaster for Vortigern. The army of ‘Hengest’ and Aesc is said to have slain 4,000 men; ‘and the Britons then forsook Kent and fled to London in great terror’. Crecganford may have sealed the fate of west Kent and so consolidated the first Saxon kingdom.

Kit’s Coty, a prehistoric tomb, is associated in legend with Catigern, leader of the British resistance to the fifth-century Saxon invaders.

The first recorded Dark Age battles, as well as many later ones, were fought by fords in rivers. The northward-flowing rivers of Kent formed natural barriers against an enemy advance towards London, and so provided good defensive positions. In the case of Crayford, the junction of two rivers forms a particularly strong defensive feature similar to those which the Vikings later used to build fortified ‘ship-camps’. The British army could be supplied and reinforced by ships from London by way of the Thames estuary and the Medway. As Caesar explained in his Gallic Wars, crossing the Medway was a particularly difficult operation as there was only one ford. In 55 bc, the Britons had fortified it with rows of stakes along the bank and driven into the riverbed. Caesar sent his cavalry across first, and their fighting élan swept all before them. Perhaps Hengest’s men, with their war-culture and battle experience, were similarly too much for the ‘softer’ British. The Saxons, too, could easily have used ships to supply their advance and perhaps prevent a British withdrawal by water.

The third battle, to which the date 465 was later assigned, was at a place called Wippedesfleot, which means Wipped’s fleet or flood. It was named in honour of a British ‘thegn’ killed in the battle, and was perhaps remembered from an elegy of that otherwise unknown warrior. Unfortunately the name of Wipped was never attached to a later settlement, and so we do not know where Wippedesfleot was. It is presumably the same place as Nennius’s third battle ‘fought in open country by the inscribed stone on the shore of the Gallic Sea’. This was evidently a well-known stone. There was such a stone, an inscription from the original gate of the Saxon Shore fortress of Richborough, which lay close to the tidal flats of Ebbsfleet, a harbour used by the Saxons. If so, perhaps the Battle of Wippedesfleot followed a bold attack on the Saxon’s naval base, with the retaking of Richborough as a possible objective. The reference to the Britons as ‘Welsh’ (Walas) has led to Wippedesfleot being included in a list of battlefields in Wales.3 In fact, the chronicler, writing centuries later, used the words ‘British’ and‘ Welsh’ interchangeably. At this date the ‘Welsh’ were not confined to Wales!

The British lost twelve ‘nobles’ in this battle, but Nennius claims that ‘the barbarians fled’, leaving Vortimer, son of Vortigern, the victor. If so, Wippedesfleot could be interpreted as a temporary reversal of the Kentish Saxons’ further campaign of conquest. However, in a fourth battle in 473, which the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle does not name, and which is missing from Nennius’s manuscript, ‘Hengest’ and Aesc again fought against the ‘Welsh’. This time the Saxons won a decisive victory, and the Britons ‘fled like fire’ leaving behind ‘innumerable spoils’. At some point, perhaps in this battle, Vortimer was killed, and with him the British lost their most effective commander.

The still impressive walls of the Saxon Shore castle at Richborough, Kent. The castle once contained a Roman triumphal arch, possibly the ‘inscribed stone by the shores of the Gallic sea’ by which Saxons and Britons fought for supremacy in the South-East.

The fourth battle marks the end of the ‘Hengest’ cycle. Nothing more is said about him in the Chronicle, but by 488 his son Aesc had become king of Kent. (We meet Aesc again in Chapter 3.) What is most puzzling about the formation of the kingdom of Kent is how ‘Hengest’ and his men were allowed to settle in such a sensitive area. By seizing eastern Kent, the Saxons had at a stroke neutralized Britain’s first line of defence. The great Roman forts of the Saxon Shore, Reculver, Richborough, Dover and Lympne, all lay in the area initially occupied by Hengest and Horsa. In the later conquests of Aelle and ‘Port’, taking the coastal forts of Sussex and Hampshire were key objectives for the Saxons. Whether ‘Hengest’ took the castles by storm, or whether Vortigern’s regime was no longer capable of garrisoning them, is unknown.

The earliest recorded battle in Dark Age Britain is this strange encounter fought somewhere in the mountainous west or north between the British forces under St Germanus and an unholy alliance of Saxons and Picts. The story was first told in a Life of the saint by Constantius of Lyons, written around 480, and repeated in Bede’s History of the English Church and People 200 years later.4 Germanus, bishop of Auxerre, had been sent to Britain by the Pope to suppress the Pelagian heresy. This taught that men may achieve salvation through their personal efforts rather than from divine grace. Germanus was an excellent choice for an emissary, having had military experience as well as a reputation as a miracle-worker. He visited Britain twice, once in 429, when he reported that the country still seemed peaceful and prosperous, and again in about 440 when things were going less well (‘The Britons in these days by all kinds of calamities and disasters are falling into the power of the Saxons’). On one of these visits, perhaps the earlier one, the Britons sought the help of Germanus and his brother bishop Lupus against the Saxons and Picts who had joined forces and were making war.

The faith and courage of the supposedly fainthearted British was buttressed by baptisms in a makeshift church. Shortly after Easter, the British forces‘fresh from the font’ advanced against the enemy in hilly terrain. The account of what happened next proceeds as follows:

Germanus promised to direct the battle in person. He picked out the most active men and, having surveyed the surrounding country, observed a valley among the hills lying in the direction from which he expected the enemy to approach. Here he stationed the untried forces under his own orders. By now the main body of their remorseless enemies was approaching, watched by those whom he had placed in ambush. Suddenly Germanus, raising the standard, called upon them all to join him in a mighty shout. While the enemy advanced confidently, expecting to take the Britons unawares, the bishops three times shouted, ‘Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!’ The whole army joined in this shout, until the surrounding hills echoed with the sound. The enemy column panicked, thinking that the very rocks and sky were falling on them, and were so terrified that they could not run fast enough. Throwing away their weapons in headlong flight, they were well content to escape naked, while many in their hasty flight were drowned in a river they tried to cross. So the innocent British army saw its defeats avenged . . . The scattered spoils were collected, and the Christian forces rejoiced in the triumph of heaven.

Having restored peace to Britain and ‘overcome its enemies both visible and invisible’ Germanus and his fellow bishops returned home.

The ‘Alleluia Victory’ is a moral tale of the power of faith (it is reminiscent of several hymns of the Church Militant, especially the one that goes: ‘Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia, The strife is o’er, the battle won’). If nothing else it is a reminder of the part magic and terror must have played in the wars of Christian against heathen. The ‘Saxons’ were overcome not only by surprise but by the realization that, on this occasion at least, their gods were not as strong as that of Germanus. The story, though obviously legendary in its details, is probably based on a real event. Place-names apparently commemorating Germanus are thicker on the ground in Powys than anywhere else, and that is also where an early tradition places the battle – though Powys would be a funny place to find a Saxon in the fifth century (the most likely invaders would be Irish Gaels). Based on place-names, the battlefield is likely to be in either the Vale of Llangollen near Correg, or near Mold in Clwyd. Just to the west of Mold is a site called Maes Garmon or the Field of Germanus (Garmon is the Welsh name for Germanus). An obelisk commemorating the battle raised there in1736 is one of the most impressive monuments to any Dark Age battle. Like the Alleluia Victory itself, belief in it having taken place here is a matter of faith.

The next cycle of battles remembered in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle begins in 477 with a new wave of Saxon invasions on the south coast. Like the warrior remembered as Hengest, Aelle (‘Ella’) crossed the Channel with very modest means – just three ships. His landing place was Cumenesora, identified with the Ower Banks just off Selsey Bill, which was then dry land. Aelle and his three sons, called Cymen, Wlencing and Cissa, were opposed near their beach-head, but, though few in numbers, they slew many ‘Welshmen’ and drove others to flight into the Andredesleag, the well-wooded area now known as the Weald. Evidently Aelle and sons were the spearhead of a new set of ‘South Saxon’ invaders which had chosen the future county of Sussex as their place of abode. Aelle is a historical figure. Bede called him the first of the bretwaldas (broad-rulers), implying that, for a short while at least, Aelle had authority over other Saxon kings.

The crucial battle was fought ‘near the bank of Mearcredesburna’ in c.485. This name means something like ‘stream of the agreed frontier’, but too little is known of frontiers at this time to be sure which stream it was. It might have been the Cuckmere near the border of what became Hampshire and Sussex. We are not even told who won the battle, which, since the source is the Saxon Chronicle, may mean that Aelle lost it. Six years later, however, in 491, Aelle and Cissa won a decided victory at Andredescester, the Saxon name for the Roman fort of Anderida, now Pevensey Castle. This was one of the forts of the Saxon Shore with high flint walls, parts of which are still standing today. The fort, now several miles from the sea, then overlooked an important harbour and a substantial settlement, whose inhabitants had doubtless taken refuge behind the castle walls. To take such a place Aelle must have commanded substantial forces, including perhaps siege equipment. The storming of Anderida probably cost him dearly. At any rate, Aelle was in no mood to take prisoners, and he ‘slew all the inhabitants; there was not even one Briton left there’.

With Anderida in flames and its garrison dead or fled, the victorious Aelle became king of Sussex, the first of a line that continued until the eighth century. Archaeological and place-name evidence indicates that the population was homogeneous. The Britons were ‘ethnically cleansed’ and the towns abandoned. The resolutely rural Saxons preferred to live in stockaded villages of wooden huts clustered around a wooden hall. The walls, colonnades, fountains and statues of the towns were left to crumble into ruins.

Another set of Saxon raiders and settlers took the remaining Saxon Shore fort of Portchester in c.501. By tradition they were led by one Port, and his two sons Bieda and Maegla, who arrived in only two ships (the number of ships in these raids consistently equals the number of sons). There is doubt as to whether Port gave his name to the city of Portsmouth, or whether the city gave its name to an anonymous Saxon leader. At all events a battle took place at Portsmutha in which ‘a young Briton, a very noble man’ was killed. Welsh tradition names this young nobleman as Geraint, who later took his place in Arthurian romance. An early ‘Elegy of Geraint’ describes his last battle at Llongborth or ‘ship-port’ which could be Portsmouth. In vigorous, if generalized terms, the poet recalls Geraint leading a charge on a white horse‘ swooping like milk-white eagles’ and ‘the clash of swords, men in terror, bloody heads’. He saw ‘spurs and men who did not flinch from spears’.5 Geraint was not a local man but a prince of Dumnonia in present-day Devon and Dorset who had come to the aid of the local Britons. It is possible that Port was not his enemy but his ally in the battle, and that their common enemy was the more formidable Cerdic, the traditional founder of Saxon Wessex.

The walls of Pevensey Castle within the Saxon Shore castle of Anderida. Here Aelle’s South Saxons besieged and massacred the Britons c.491.

Cerdic is a well-known if shadowy figure. In Alfred’s day, the kings of Wessex traced their ancestry back to Cerdic, who first appears in the Chronicle in 494, immediately after the ‘Aelle cycle’. But Cerdic is an odd name for a Saxon king. It is Celtic, probably a variant of ‘Caradoc’. Was Cerdic a renegade Briton? According to one quite plausible legend, Cerdic was a British nobleman from Winchester (the Roman Venta) who subsequently emigrated and spent his life among the Saxons across the Channel. His tribe was eventually pushed westwards by the Frankish leader Clovis, and so Cerdic decided to seek his fortune in his old homeland. Thereupon this former Briton, now Saxon by adoption, carved out a kingdom of his own, having overcome his former compatriots in battle. Alternatively he could be a semi-legendary ancestral figure around whose shadowy form the names of remembered wars and battles began to cluster.

Cerdic’s battles, which were retrospectively given dates between 494 and 530, are centred on Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. Several of them are named after Cerdic himself. He is said to have arrived in Britain with his son Cynric and five ship’s companies. As Aelle had done, he fought his way ashore at an unknown place simply called Cerdices ora, or Cerdic’s shore. Then, in c.508, Cerdic and Cynric ‘slew a Welsh king, whose name was Natanleod, and five thousand men with him’. Natanleod did not necessarily come from modern Wales; more likely he was a local British ruler. The district in which the battle was fought was known afterwards as Natanleag, meaning ‘wet wood’ (the ‘g’ is silent, hence it is pronounced ‘Natanley)’. There are two Netleys in Hampshire, one by Southampton Water between the Itchen and the Hamble, and the other near Old Basing in the north-east corner of Hampshire, where tradition records an ancient battle on the still wet and boggy Greywell Moor. There is also a lost village of Netley in the New Forest, remembered in the name of Netley Bog. According to tradition, Cerdic took Winchester after the battle and established a heathen temple there on the smoking ruins of the old church.

In 514 yet another group of ‘West Saxons’ under Stuf and his son Wightgar landed at Cerdices ora with three ships. Like Cerdic, they fought a battle there ‘and put the Britons to flight’. According to the Chronicle, these two were close relations (nafa) of Cerdic; they may have been Jutes. The climactic encounter of the series took place at Cerdicesford – another battle at a river crossing – in 519, by established tradition the year the West Saxon kings began their rule (however a lost version of the Chronicle used by the tenth-century chronicler Aethelweard has him establishing a kingdom c.500). Again, the site of Cerdicesford is unknown, though Charford by the River Avon in Hampshire between Downton and Breamore has been suggested.

Cerdic’s last battles were fought at an unknown Cerdicesleag (Cerdic’s-ley or Cerdic’s wood) in 527, and at a place later known as Wihtgaraesburh (Wightgar’s fort) on the Isle of Wight in 530, where they found that most of the inhabitants had fled before their arrival. The capture of the Isle of Wight at about this time is confirmed by the Welsh annals, although the Isle’s name is borrowed from Wightgar, not Cerdic. Wihtgareaesburh was probably on the site of Carisbrooke Castle near Newport. The medieval castle stands on the remains of a late Roman fortified building which may have been among the forts of the Saxon Shore. According to the Chronicle, Cerdic on his deathbed ceded the island to Wightgar and his Jutes. Cerdic died in c.534. His burial place at Cerdicesbeorg has been identified with Stoke, near Hurstbourne in north-west Hampshire.

The locations of Cerdic’s battles suggest that he gradually enlarged his territory in south Hampshire. The area around the New Forest and the Hamble was known in Bede’s time as the Jutish Nation, suggesting that it was in fact Stuf and Wightgar’s tribe that settled here, not the ancestors of the later Wessex kings. Inevitably, given his dates, Cerdic has become entangled with the Arthurian legend. He arrived shortly before 496, the most probable year for ‘Arthur’s’ climactic battle at Mount Badon (see next chapter), and Arthurian theorists have linked Cerdic’s battles with some of the legendary twelve battles of Arthur listed in the Historia Brittonum. One of these, fought by ‘the river called Dubglas’, might have been Natanleag, while ‘the battle on the river called Bassas’ might be the same battle as Cerdicesford. ‘The battle in Guennion fort’ could be ‘Wihtgarasburh’. The evidence is based on Romano-British place-names, such as the Welsh name ‘Gwyn’ for the Isle of Wight, aided by a lot of speculation. Cerdic and Arthur belong to a time when legend and history are hopelessly entangled. Whether Cerdic and Arthur ever met, or even whether either of them ever existed, is something theorists will continue to argue about – perhaps without ever coming to a firm conclusion!

Apart from Cerdic’s adventures in Hampshire, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle has little to say about the first half of the sixth century. The next cycle of battles and conquests begins in 547, with the building of a fortress at Bamburgh by Ida, the leader of a war-band of Angles and the traditional founder-figure of the kings of Northumbria. But it has nothing to add about Ida’s subsequent career except that he ruled his little kingdom for twelve years. Instead, the Chronicle turns to the exploits of Cerdic’s descendants in the south. The brief annal for 552 celebrates Cerdic’s son, or possibly grandson, Cynric (as he crossed the sea with Cerdic in 494 he would have been at least in his seventies) who besieged the Britons at Searoburh. Four years later, he and his son Ceawlin fought the Britons at Beranburh, and then, after an interval in which Ceawlin fought against his fellow Saxon king Aethelbert, came what was clearly an important battle at Deorham in 577. The Britons were slaughtered at Deorham, and afterwards the cities of Cirencester, Gloucester and Bath fell to the Saxons.

The impression is of a sustained campaign of conquest which resulted in the collapse of the British kingdoms in the upper Thames and lower Severn area. This is broadly borne out by archaeology, which shows Saxon settlements spreading across central southern England at this time and the fall of key British towns. For example, Silchester, the ‘capital’ of tribal lands in Berkshire and the middling reaches of the Thames valley, remained a functioning walled town throughout most of the sixth century, but had evidently become a deserted ruin by its close. One sign that the Britons were losing control of central southern England was their re-use of long-abandoned Iron Age hill-forts. Excavations at the hill-fort at South Cadbury in Somerset revealed that the original earth ramparts had been refortified with a 4,000-feet long stone-dressed timber platform at this time and the entrance defended by a gate-tower. The walls enclosed a large hall and other substantial buildings, and was no doubt occupied as the headquarters of an important personage.

There is no evidence that South Cadbury was attacked, but the Chronicle’s Seoroburh and Beranburh were both fortified places which can be securely identified with the elaborate hill-forts at Old Sarum near Salisbury and Barbury Castle on the Ridgeway south of Swindon. Seoroburh or Saerobyrig was later Normanized as Sarum, and became ‘Old Sarum’ after the inhabitants moved from the windy hilltop into the valley and built a new city at Salisbury. Seoroburh had been the Roman town of Sorviodunum, and lay at the conjunction of the Roman roads from Winchester, Silchester and Dorchester. It was heavily fortified with multiple rings of earthworks and had its own water supply. It was large enough to enclose the later Norman castle and cathedral as well as a bustling small town. Seoroburh‘s capture was clearly an important milestone in the Saxon Conquest of southern England. How it fell, whether by storm or after a field battle fought outside, we are not told, and archaeological evidence has not yet provided any clues. The Chronicle states simply that ‘Cynric fought against the Britons at the place called Seoroburh, and put the Britons to flight’.

This sudden aggressive surge by the West Saxons may be due to the emergence of a new leader, Cynric’s son Ceawlin (chey-awlin). He is not mentioned at the capture of Seoroburh, but was with Cynric at Beranburh in 556, and succeeded him as king of the West Saxons in 560. Beranburh or Barbury lies just above the Ridgeway close to a strategic intersection of Roman roads. The double walls are still impressive today and it must have been a formidable obstacle in the sixth century when it had no doubt been restored and refortified. Barbury Castle encloses four hectares, room enough for a substantial military garrison, and excavations there suggest that the fort was in use from the Iron Age, through the Roman occupation and into the Dark Ages. It stands close to another hill-fort at Liddington Hill, a contender for site of Mons Badonicus or Mount Badon, fought half a century earlier (see Chapter 3). The Saxons probably approached from the east using the Ridgeway and so attacked from the north. The capture of Barbury would bring the Ridgeway under Saxon control and open up the further advance towards Cirencester or Bath.

The Chronicle says only that the Saxons fought the Britons there, not that the Saxons were victorious or that Barbury was taken. The natural assumption is that it was not taken, and that the attack was beaten off. Things then go quiet for a decade, and when we hear of Ceawlin again it is in the context of a war against his neighbour to the east, Aethelbert, king of Kent, and not against the Britons. Beranburh may therefore have been a British victory to rank with the Battle of Mount Badon. Against Aethelbert, Ceawlin was more successful. The two Saxon armies met at a place called Wibbandun in 568. From the similarity of their names, Wibbandum has been equated with Wimbledon in south London. Opinion today is that the battle was more likely fought near the River Wey which divides Surrey from the then kingdom of Kent. Whitmoor Common between Worplesdon and Guildford is a possible battle site. The result was that Aethelbert was driven back with the loss of two Kentish ‘princes’, Oslaf and Cnebba. This is the same Aethelbert who, nearly forty years later, allowed St Augustine to convert the Saxons of Kent and became the first Christian Saxon king. By now the Dark Ages are becoming a little lighter.

The walls of Barbury Castle: scene of a great battle between Briton and Saxon in 556. The battlefield may lie between the castle and the Ridgeway, here passing below the downs 400 m to the north.

The 570s saw the decisive turning-point in the see-saw wars between Briton and Saxon. In 571 a West Saxon kinglet called Cuthwulf fought against the ‘Brito-Welsh’ (Bretwalas) at Biedcanford and captured four villages (tuns), identified as Limbury, Aylesbury, Benson and Eynsham. Cuthwulf died shortly afterwards, and perhaps was mortally wounded in the battle. The location of Biedcanford is uncertain. The obvious match is with Bedford or ‘Beada’s ford’, but that redundant ‘c’ is problematical. The only way Biedcanford could be made Bedford is if the original scribe had made a spelling mistake that was then copied faithfully by all the other scribes. But the battle was clearly fought by a river, perhaps the Ouse. The significance of the battle is that it seems to represent the mopping up of the last British enclave in south-east England, and may therefore have opened up the Midlands to conquest. Biedcanford decided the fate of the area broadly covered by the Chilterns and the Vale of Aylesbury, an area known by the next century as the Chilternsaete, an area of 4,000 hides of land (it survives today as ‘the Chiltern Hundreds’). The four seemingly insignificant places mentioned by the annalist cover a wide area: Eynsham and Benson are in central Oxfordshire, Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire and Limbury is now a suburb of Luton. They were perhaps the fortified settlements of local magnates who were now overthrown once and for all. Archaeology shows no Saxon settlement in this area much earlier than 570.

The year 577 saw the climactic Battle of Deorham. It was important enough to be recorded woefully in the Welsh annals as ‘the battle we lost’.6 Deorham was Ceawlin’s finest hour, the day when he finally cracked the stubborn British hold on ‘the strategic triangle’ defined by the Roman roads linking Cirencester, Gloucester and Bath. The British leaders were killed in the battle, and the cities all taken. It was perhaps after Deorham that Ceawlin was hailed as the second bretwalda of the Saxons. He may not have been the most powerful king in terms of territory – Ceawlin nearly always made war with allied war-lords – but he personified qualities that the pagan Saxons respected most: courage, dash, wisdom in battle and a sense of destiny. He was a true Dark Age hero; it is a pity we do not know him better.

Fortunately we do know where Deorham was. It is the modern village of Dyrham a few miles north of Bath, whose name means ‘deer enclosure’ or ‘deer park’. There has been a deer park there at least since the Middle Ages, which evidently had a Dark Age precursor. We can only speculate why the battle was fought at this deeply rural spot among the Cotswold Hills. Perhaps Ceawlin, who was accompanied by his son Cuthwine, had changed his strategy from besieging hill-forts to a mobile strike into the heart of enemy territory. He seems to have chosen to march through the ‘strategic triangle’, avoiding the strongly defended cities and aiming to isolate the Britons of the Severn valley from those of Somerset and Devon.

The strategic triangle, 496–577

The British massed to oppose him, led by three ‘kings’ (kyningas in the Chronicle, tyranni in British sources) named as Coinmail, Condiddan and Farinmail. It is assumed, though not explicitly stated, that they were the respective rulers of Gloucester, Cirencester and Bath. Like their compatriots at Beranburh and at Badon, they would have refortified the hill-forts, and it can be assumed that they rendezvoused at one of them: Hinton Hill Camp, between the villages of Dyrham and Hinton, and within a short march on mostly good roads from all three cities. They were hence in a good position to intercept Ceawlin, if, as they probably expected, his objective had been to take the city of Bath.

The landscape around the village has invited much speculation about how the battle may have been fought. Hinton Hill Camp lies on a spur of land above the Cotswold escarpment which slopes away to the west and on both flanks. It does not lie on an important road – the Fosse Way runs straight as an arrow several miles to the east – but Dyrham lies on an ancient track running westwards from Wiltshire via Nettleton, Stanton St Quinton and Christian Melford. Most likely Ceawlin advanced this way from the Marlborough Downs. His scouts having located the Britons massed at Hinton Hill Camp, Ceawlin decided to attack.

Alternative reconstructions of the Battle of Deorham by Burne (right) and Smurthwaite (left)

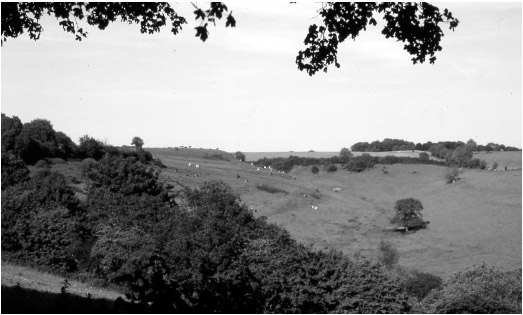

The battlefield of Deorham in Alfred Burne’s interpretation as seen from Hinton Hill Camp. Ceawlin’s Saxons stood on the further ridge, the Britons under their three kings on the ridge nearest the camp.

The best interpretation of the Battle of Deorham is Alfred Burne’s in More Battlefields of England.7 Burne found two ridges in front of the camp along Ceawlin’s likely line of advance, one close to the camp, and another slightly higher one 300 yards further forward. He proposed that the British had occupied the forward line, with the other as a fall-back position. For what followed Burne seized on the one detail we know but whose significance had been overlooked: that all three British leaders were killed in the battle. Burne regarded this circumstance as unique (though it also happened at Hastings) and concluded that the British army must have been surrounded. If so, the lie of the land suggests how it might have happened. The Britons were pushed back towards the hill-fort. Then the wings of Ceawlin’s army outflanked them by charging downhill and instinctively swinging inwards (‘as troops do’). The Saxons joined hands in the rear of the hill-fort and cut off the Britons’ line of retreat. The fort was then besieged, and, if still alive, the three kings were captured and then ‘knocked on the head’.

Of course there are other possible interpretations of what might have happened. The British could have chosen to stay inside the fort with the hope of counterattacking at the right moment, as they evidently did at Mount Badon. Or it may have been a contact battle and not involved the hill-fort at all. David Smurthwaite suggests that the Saxons attacked at dawn from the escarpment, sweeping away the Britons in the valley below before they could form up to receive the charge.8 If so, the battle that decided the fate of Wessex couldhave been over in minutes. However it turned out, with the annihilation of the British field army and the death of their leaders, the three cities fell to Ceawlin.

Ceawlin’s view looking towards Hinton Hill camp (marked by the trees in the distance).

Another view of the Battle of Deorham has Ceawlin occupying the heights above the present village and falling on the Britons as they advance. The field system shown so clearly on the scarp slope probably pre-dates the battle.

The archaeological record suggests that Cirencester and Bath both fell without a fight. It was at this point that their names changed from the British Caer Ceri and Caer Baddan to the Old English Cirenceaster and Bathanceaster. The victory marked the beginning of Saxon settlement in the Severn valley and the creation of the kingdom of the Hwicce in modern-day Worcestershire and Gloucestershire. While the Saxons could now sweep from the Cotswolds into the fertile lowlands of the Severn, the British could no longer easily penetrate the Cotswolds. Henceforth the western Britons were increasingly isolated in the far west, in Wales, and in Cornwall and Devon.

After Deorham, Ceawlin’s triumphant career went into reverse. In 584, he and ‘Cutha’ (probably the same person as ‘Cuthwine’, and if so his son) ‘fought against the Britons at a place which is called Fethanleag, which means ‘‘battle-wood’’ ’. Though Cutha was slain in the battle, the Saxons may have won it since Ceawlin went on to capture ‘many villages and countless booty’. However things did not go as he intended for he soon ‘departed in anger to his own’, that is, his own land. From place-name evidence, Fethanleag was first identified as Faddiley in Cheshire, but this seems an unlikely place for the battle. Sir Frank Stenton identified it much more plausibly with Stoke Lyne, near Ardley in Oxfordshire, from a medieval charter mentioning a wood then called Fethelee.9 Stoke Wood, Stoke Little Wood and Stoke Bushes may be fragments of the original, much larger, ‘Battle Wood’. The nearby village names include Fringford, Fritwell and Hethe, which have echoes of the lost Old English wood. Another village, Cottisford, could possibly be named after the dead Cutha. Cutha is said to have been buried in a magnificent barrow by the road at Cutteslow, now a northern suburb of Oxford. The barrow is unfortunately long gone – it was demolished in 1261, an early victim of a road improvement scheme (the barrow was a haunt of robbers on the king’s highway).

Ceawlin’s last battle was fought in 592 at Wodnesbeorh, where ‘there was much slaughter’. ‘Woden’s Barrow’ has been plausibly identified with Adam’s Grave on the Pewsey Downs. A large Neolithic long barrow surrounded by a ditch, it crowns the summit of Walkers Hill a mile from the village of Alton Priors. Adam’s Grave was originally ‘Woden’s Grave’, and the name seems also to have been borrowed by the village of Woodborough, visible beyond Alton Priors from the hill-top. Wodensbeorh seems to have been a civil strife in which Ceawlin was ‘driven out’, that is, deposed, by a younger relative called Ceol. The twelfth-century historian William of Malmesbury got hold of a story that the battle was ‘the result of the Angles and the British conspiring together’. Perhaps therefore Ceol had been helped by the Britons, as King Penda was to be in the next century (though not against his own kith and kin). The battle was probably fought in the pass between the downs between Walkers Hill and Knap Hill. That this was then a boundary of some sort is indicated by the contemporary Wansdyke snaking over the downs just north of Adam’s Grave. There was a second battle here in 715 when the kings of Mercia and Wessex fought on the same spot.

The site of Ceawlin’s last battle: Walker’s Hill, as seen from Knap Hill in the vale of Pewsey. Wodensbeorth or Woden’s Barrow is Adam’s Grave, the Neolithic long barrow that crowns Walker’s Hill.

Perhaps Ceawlin tried and failed to force the passage over the downs in an attempt to retake his hard-won lands north of the Wansdyke. It is tempting to assume that the dyke played some part in the battle, but we can only speculate what might have happened, and why it was named after the barrow and not the dyke.

The Chronicle’s record for 593 consists of a bare sentence: ‘In this year Ceawlin and Cwichelm and Crida perished’. Perhaps Ceawlin had formed an alliance with the other two and fell attempting to retake his ‘own’. The wording suggests that the three fell together in the same incident. Ceawlin’s death closes the cycle of battles and campaigns of the Saxon Conquest of southern England. Ceol’s successor Ceolwulf, son of Cutha, seems to have led his war-band far and wide, ever fighting ‘against the Angles, or against the Welsh, or against the Picts, or against the Scots’. But the Chronicle records not a single one of his battles. Quite abruptly, the record switches to a different kind of conquest. In 601 St Augustine came to England as head of a papal mission to convert the English to Christianity. Cynegils, the son of the warlike Ceolwulf, became the first Christian king of the West Saxons. Unlike his predecessors he rests not under the turf below the wind and sky but in the sanctuary of Winchester Cathedral among bishops and saints.