For the seventh-century kings of Northumbria, Dunnichen was a long way from home. Bede refers to it as ‘a tight place of inaccessible mountains’ and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as a remote land ‘by the northern sea’(be northan sae). Dunnichen lay deep in the heart of a Pictish kingdom known as Fortriu (pronounced ‘fortry’), which broadly coincides with today’s Scottish district of Tavside. The affairs of the kings of Fortriu are recorded only at secondhand, and always very briefly, in the Irish annals. In the seventh-century melting-pot there was much interplay between the various kingdoms of northern Britain. The dominant power was the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria, which was then at the apogee of its power. To the north lay the ever-shifting tribal kingdoms of the Picts, which included Fortriu, the Scots and the Britons. The power of Northumbria at times extended over a large area beyond the present-day border at least as far as the Forth. This was particularly so during the reign of King Ecgfrith of Northumbria, who ruled from 670 to 685. Ecgfrith’s southern ambitions had been checked, and he turned instead to Ireland, and to the lowlands north of the Forth. Ecgfrith (pronounced ‘edge-frith’, with a soft ‘th’as in froth) is one of the protagonists in our battle. What took him to Dunnichen?

The answer is only hinted at in the sources but it involved his dealings with a brother king called Bridei. Shortly after he succeeded his father Oswy in 670, Ecgfrith fought a battle against the Picts at a place called the Two Rivers. The only account of it is in the Life of St Wilfrid, written c.720 by a monk called Stephan. When Ecgfrith was still attempting to establish his rule, ‘while the kingdom was still weak’, the Picts rebelled. ‘The bestial Pictish people’, writes Stephan, began to ‘throw off from themselves the yoke of servitude’.1 It seems that they overthrew Northumbria’s client-king, called Drust, and refused to pay further tribute to Northumbria. Doubtless they also signalled their rejection of Northumbrian power by raiding Anglian settlements south of the Forth.

Stephan relates how the Picts prepared for war, gathering ‘like a swarm of ants in summer, sweeping from their hills’. ‘Being a stranger to tardy operations’, King Ecgfrith forthwith assembled a mounted force (equitatus exercitus), and rode north. Though outnumbered by a vast and concealed enemy, he ‘slew an enormous number of the people’. Stephan repeats the legend that two rivers were filled with their corpses ‘so that wondrous to relate the slayers, passing dry-foot over the rivers, pursued and slew a crowd of fugitives’. By these means, the Picts of that region were once again ‘reduced to servitude’.

The location of the Two Rivers is unknown, though it evidently lay north of the Forth. One of the rivers was probably the Tay, the other possibly the Almond or the Earn, though this is only a guess. By means of this victory, Ecgfrith overthrew the Pictish leader, who was succeeded by the seemingly more compliant Bridei, son of Beli also spelt Bruide or Brude in some sources, and pronounced Bridey or Broody according to taste. It seems that he and Ecgfrith were related in some way; indeed one Irish annal refers to them as brothers ( fratrueles).2 They cannot have been literal brothers, but they could have been cousins by marriage and may both have been grandsons of King Edwin.3 They were also both second-generation Christians. In gratitude for helping him to the throne it was no doubt expected that Bridei would be a friendly and subservient tributary king, as his predecessors had been in the days of King Oswy.

As a king whose imperium or overlordship stretched well beyond his nominal kingdom in northern England, Ecgfrith spent much of his reign confronting hostile neighbours. The greatest threat, as for his predecessors, came from south of the Trent from the kingdom of Mercia. In c.673, Ecgfrith defeated the Mercian King Wulfhere, son of Penda, at an unknown and unnamed battlefield.Butin678 or 679Wulfhere’s successor and younger brother Aethelred turned the tables and decisively defeated Ecgfrith at ‘a great battle near the River Trent’. Its location is unknown, but Elford near Lichfield, Staffordshire, has been suggested on the grounds that Elford may mean ‘Aelfwine’s ford’ (although Elford lies on the Tame, not the Trent). Aelfwine was Ecgfrith’s well-regarded younger brother, who lost his life in the battle. Ecgfrith may have been attempting to reimpose his father’s policy of divide-and-rule over the large and loosely knit Midland kingdom. At any rate, the Trent seems to have been a serious and possibly decisive battle. Never again would a Northumbrian king be able to exert his will over his powerful southern neighbour, as Ecgfrith’s father and uncle had.

Instead, Ecgfrith turned his attention to Ireland. In 684, the year before Dunnichen, Ecgfrith dispatched an expedition to Ireland under a deputy (dux) called Berct to punish an Irish kinglet for lending support to his enemies. ‘In the month of June [684]’, record the Annals of Ulster, ‘the Saxons lay waste Mag Breg [i.e. the plain of Brega in County Meath], and many churches’. Berct’s actions were deplored by contemporary churchmen, and not just in Ireland. In hindsight, it seemed that God was about to punish Ecgfrith for, in Bede’s words ‘wretchedly wasting a harmless people that had always been friendly to the English’.4

Bede links these events in Ireland with Ecgfrith’s expedition to Dunnichen the next year. The outraged inhabitants of Brega prayed for divine vengeance, and those responsible, claimed Bede, soon ‘suffered the penalty of their guilt . . . Ecgfrith’s punishment for his sin was that he would not now listen to those who sought to save him from his own destruction.’Did the Irish expedition stir up trouble in Fortriu? Or was Bridei already on a collision course with his cousin? Success for a Dark Age king was measured by the extent of his imperium: the more land he ‘ruled’, the wealthier he became, and hence his ability to reward his chief men, raise large armies and defend his frontiers was increased. Bridei was no exception. He was connected by blood and alliance to a network of Celtic and English kingdoms. One source claims that Bridei’s father Beli was the king of British Dumbarton,5 and another that the kingdom of Fortriu was the inheritance of his grandfather.6 He may therefore have imposed his rule over an unusually large area, and been able to call on human resources considerably greater than an average tribal king.

Be that as it may, Bridei definitely had ambitions. With no possibility for the moment of extending his imperium southwards, he looked north and west. Around 680 he attacked the stronghold of Dunnottar, on its rock near modern Stonehaven, and a few years on took Dundurn (Dunduirn), a Pictish fort at the foot of Loch Earn in the Trossachs. More surprisingly, he is said to have ‘annihilated’ the inhabitants of Orkney,7 which suggests a Viking-like leader at the head of a marauding fleet (the unlikeliness of an obscure king of Tayside sailing halfway round Scotland to trash the Orkneys is a reminder of how little we know about the Picts). Bridei was a ‘wide ruler’on the make. Perhaps events on theTrent and in Breda encouraged him to make the momentous and perilous decision of breaking with cousin Ecgfrith and denying him his annual tribute of cattle, corn and gold. Or perhaps Ecgfrith had decided that cousin Bridei was getting too big for his boots and prepared to overthrow him as he had Bridei’s predecessor. Bede, the main authority, saw the events of 685 in a different light. By ignoring sensible warnings, Ecgfrith was treading a divinely ordained path. His refusal to heed advice created its own punishment.8

Scholars do not always agree about the name of a battlefield. Although the decisive battle of 1066 was known as the Battle of Hastings within a generation of the event, many authors have followed the nineteenth-century historian E A Freeman in preferring to call it the Battle of Senlac. The battle which brought the Tudors to the throne was apparently known nearer the time as the Battle of Redemore, but posterity has preferred the Battle of Bosworth or, as Shakespeare knew it, ‘Bosworth Field’.

The battle in which the Northumbrian English fought the Picts in what is now Scotland in 685 has been known by several names. Until recently it was the Battle of Nechtansmere, or, in the original Old English spelling, Nechtanesmere.This may well have been the contemporary name of the battle in Saxon England, though its first documentary appearance is in a twelfth-century chronicle as stagnum Nechtani,the lake (or possibly bog) of Nechtan.9 The earliest source refers to it only as ‘Ecgfrith’s Battle.10

The English lost the battle.What did the winners call it? The ancient Picts have left no written history, but the Irish annalists knew it as Bellum or Cath Dun Nechtain,that is, the Battle of Nechtan’s dun or hill-fort.11 It seems a fair bet that Nechtan’s fort lay in the same area as Nechtan’s lake. An alternative name recorded in the Welsh Historia Brittonum is Gueith Lin Garan, the Battle of the Heron Lake, a name which, the annalist tells us, goes back to the time of the battle.12

A good case has recently been made for a name-change by the battle’s most zealous investigator and promoter, Graeme Cruickshank. In place of Nechtansmere, he proposes the Battle of Dunnichen.13 Most historians accept that Dun Nechtain, whether it refers to a particular hill-fort or the broader lordship around it, lay in the vicinity of the modern village of Dunnichen (though its present-day inhabitants live in the valley rather than on the hill-top). The clinching evidence lies in a twelfth-century charter confirming lands on Arbroath Abbey in which the place is referred to as Dun-Nechtan. The new name is certainly a useful corrective to the usual England-centred view of history, and has been adopted in the most recent account of the battle by James E Fraser.14 Personally I would regret the passing of Nechtanesmere, which, to me at least, has a mystical quality, akin to Arthur’s Avalon and with the added advantage, given the nature of Dark Age sources, that it does not anchor the battle to a particular place on the map. But to the victor go the spoils, and it seems only fair to give Dunnichen an airing. Let us hope the battle was really fought there!

The traditional site of the Battle of Dunnichen, Dunnichen Hill in the background, and a flight-pond, dug in the 1990s on the supposed site of Nechtansmere.

Ecgfrith’s expedition set out in April or May 685, once the grass had grown tall enough to feed the horses. Judging from Stephan’s description of his equitatus excercitus at the Two Rivers, this expeditionary force may have been a surprisingly small one, perhaps more comparable to the 300 valiant warriors who fought at Catterick than a vast levied army.15 His strategy was evidently to strike fast and hard, before the scattered enemy could muster a large enough army to oppose him. Such raids were designed to weaken the enemy more by ravaging his lands than by bringing him to battle. Two Rivers may have been less a pitched battle and more of a running series of strikes.

In his closely argued reconstruction of the battle, James Fraser proposed a tight-knit mounted army for Ecgfrith, consisting of the young unmarried men of his household seasoned with more veteran warriors. We are given none of their names, though we know the king was accompanied for at least part of the way by his bishop Trumwine. Other members of his family seem to have been with the king, for a monk of Lindisfarne referred afterwards to ‘the fall of the members of the royal house by thecruel hand of ahostile sword’at Dunnichen.16 Whether Berct, the despoiler of the Bregan churches, or Beornheth, the ‘brave sub-king’who had helped his master at the Two Rivers, were with Ecgfrith we do not know. We can assume, however, that the king commanded an elite force, many of whom had previous battle experience. Nor need we doubt that they knew exactly where they were going and what they were going to do when they got there.

Ecgfrith probably mustered his men at Bamburgh rock (Bebbanburg), the main stronghold of his homeland of Bernicia. The road to Edinburgh (Din Eidyn)probably took him along the coast, on the same route as Edward I took when he invaded Scotland in 1296. Beyond Edinburgh there was a Roman road as far as Perth, and a series of old Roman marching camps stretching through Strathmore and beyond. Whether by coincidence or not, one of them, at Kirkbuddo, lies only four miles from the battlefield at Dunnichen. Until he reached Abercorn (Abercurnig), Trumwine’s monastery on the Forth, Ecgfrith was on home turf. He could summon men to his army as he rode. Punitive operations probably began in Strathearn around the crossings of the Earn and the Tay, a fertile area, in James Campbell’s words,‘well worth ravaging’. The burning of Tula Amain, a settlement where the Almond meets the Tay, may have been part of the ‘ravaging and laying waste’ remembered by the monk of Lindisfarne during the reign of Ecgfrith’s successor.

Apparently meeting little resistance, Ecgfrith crossed the Tay and headed north-east through the broad valley of Strathmore, probably along the line of the present A94 from Perth and Scone to Forfar. His objective was probably Bridei’s main stronghold in the area. But where was it? Fraser suggests Turin Hill, which is crowned by a large dun now known as Kemp’s Castle. The hills and vales around Forfar are particularly rich in hill-forts and contemporary Dark Age stones, which argue that it was an important place in Pictish times, both in terms of defence and perhaps also in some spiritual way. Now drained and cultivated, it is not easy to imagine the area in the distant seventh century when long shallow lochs stretched down the valleys with small wooded or cattle-grazed hills rising through the mist. With formidable natural defences, this was truly an ‘inaccessible’ land, to borrow Bede’s words. In certain lights and weather-moods it must have seemed an eerie place to outsiders, a mingling of land, stone and water unlike anything they had seen in northern England.

Did Ecgfrith get lost? According to Bede, the enemy pretended to retreat, luring him into this dangerous area with its plentiful ambush possibilities.17 But Fraser points out, reasonably enough, that Ecgfrith was an experienced warrior, would have used scouts and must have had at least a rough knowledge of the local geography. He was unlikely to have blundered on, frustrated and heedless, into an obvious trap. Yet that is exactly what F T Wainwright makes him do in a celebrated paper in the journal Antiquity.18 Wainwright based his reconstruction of the battle on the depression of a vanished lake near Dunnichen which had partly filled with water in the wet winter of 19467. Map investigation indicated that this was the site of Dunnichen Moss, a boggy area in the valley bottom which had been partly drained and reseeded c.1800 (it was famous in the botanical world as the only known site of the ‘cotton deer-grass’).

The site of Wainwright’s Nectansmere, now drained levels grazed by sheep.

Bogs often grow over the sites of shallow lakes. Could Dunnichen Moss have been the site of the lost Nechtanesmere, the lake of herons? Wainwright thought so, and so, following him, did a whole generation of historians before 1996 (including myself, in my book Grampian Battlefields). The terrain suggested to Wainwright a scene in which Ecgfrith’s army would have burst through the cleft in Dunnichen Hill only to fall straight into an ambush set by the Bridei. The Picts, massed inside the walls of their fort on the hill-top, must have raced down the hillside to attack the Saxons and drive them back to the boggy shores of the lake where they were cornered and cut to pieces. It is the site of Wainwright’s Nechtanesmere that is now marked by the Ordnance Survey’s crossed swords of battle, and it is by the village church, overlooking this battlefield, that a monument was raised on the 1,300th anniversary of the battle in 1985.

There is some evidence for this supposed lack of caution on Ecgfrith’s part. Bede condemns his ‘rashness’ in being lured into remote and dangerous country by the enemy. But the problem with Wainwright’s battlefield, as I discovered when I went there twenty years ago, is that the top of Dunnichen Hill is visible for miles around. Ecgfrith would have needed to be blind as well as heedless to ignore it. One overlooked clue to the battle is the use by Irish and English sources alike of the word bellum.As Fraser points out, for an ambush ormassacre the words interfectio or strages would be more appropriate. Bellum is the word for an open engagement, in other words, a battle. Both language and military probability suggest a different kind of battle by a different lake in the vicinity of Dunnichen Hill.

Monument to the battle, erected close to Dunnichen church on its 1,300th anniversary in 1985.

In a timely reassessment of the battle, Leslie Alcock suggested that the fatal lake, Nectanesmere was not at Dunnichen Moss, after all, but at Restenneth Moss, two miles to the north-east, where another now-vanished lake once lay.19 But would such a place, two miles as the crow flies from Dunnichen Hill, have been called Dun Nechtain? Possibly.One point in its favour is the presence of Restenneth Priory on what was once a promontory on the lake’s southern shore. The priory is believed to have been founded in the early eighth century within living memory of the battle, and, if so, it is tempting to see a connection. If it is the same place as Naiton’s church, built by English masons from Monkwearmouth on the Tyne, it might have symbolized reconciliation between the two nations after good relations had been restored by Ecgfrith’s successor. Churches had certainly been built on battlefields earlier in the century, notably at Maserfeld and Hefenfeld.

However, Alcock overlooked geographical history. Analysis of peat-core samples from the valley floor indicate that Restenneth Moss was once part of a much larger lake that also took in the present-day Loch Fithie, Rescobie Loch and Balgavies Loch; in other words, that Nechtanesmere, if this be it, must have been a large lake around four miles long, though little over half a mile wide. Moreover it stood only a few miles to the east of another long lake, the original Loch of Forfar, leaving only a saddle of land in the vicinity of the modern town of Forfar where an army could cross the valley.

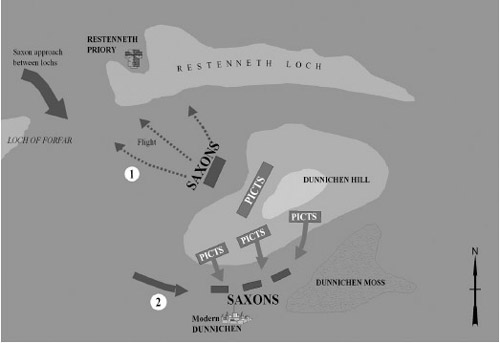

To Fraser, this Dark Age topography suggests a likely battlefield on Green Hill, a northward extension of Dunnichen Hill between Burnside Farm and Loch Fythie.20Here one can imagine the Picts arrayed in conventional battle order on the hillside as Ecgfrith’s army crossed the tongue of land between the lochs and approached Dun Nechtan from the west. In this reconstruction the English precipitated the battle, although they were at a disadvantage with limited space to manoeuvre on the dry land between the hill and the lake.

For the battle itself, we are dependent on an unconventional and controversial source. This is not a written document but a stone, a beautifully carved upright slab about seven feet high called the Aberlemno Stone. Today it stands in Aberlemno kirkyard four miles north of Dunnichen Hill, but only two from Turin Hill, which, as Fraser suggests, may have been Bridei’s ‘capital’ and Ecgfrith’s objective. On one side is a Celtic cross, richly carved in high relief and with decorative motifs in the corners. On the other is a portrait of a battle. There are nine figures in all, arranged on three levels. At the top we see two mounted soldiers galloping from left to right. In the middle three men on foot face another mounted soldier cantering in from the right. And at the bottom two mounted soldiers face one another. To their right a figure larger than the rest is apparently sprawled on the ground where he is being pecked by a large bird. The juxtaposition of the Christian cross on one side and pagan symbols on the other suggests a date for the stone from the eighth or ninth century. The battle scene is unique in its vividness and complexity. But what battle is it, and why did it merit this exceptional monument?

Alternative reconstructions of the Battle of Dunnichen

Past generations assumed that the Aberlemno Stone refers to some biblical event, perhaps to the fall of King Saul, or alternatively to some unidentifiable conflict between northern tribes. However, in 2000 Graeme Cruickshank made a powerful and persuasive case that the scene on this stone is none other than the Battle of Dunnichen!21 The argument turns on the proximity of the stone to the battle field, its probable dateand the details on the stone itself.To my mind the most convincing evidence is in the details of arms and armour shown on the stone. Three of the horsemen, as well as the crow-pecked figure on the ground, wear helmets with neck-guards and long nose-guards that are strikingly similar to the Coppergate Helmet excavated at York and which has been dated to c.750. They also wear some form of body armour, perhaps mail hauberks which are split at the hip for fighting on horseback, much like the hauberks of the Norman cavalry on the Bayeux Tapestry. They fight with shields and lances. Their horses too have quilted protection along the body. This is evidently an aristocratic army, well-equipped household warriors with war-horses and body-armour.

By contrast, their adversaries seem be less well armed, lacking helmets and wearing only light knee-length tunics. They have beards and shoulder-length hair and carry round shields with a big central spike. They fight with spears and, in one case, a short sword. With the exception of a single mounted warrior they fight on foot in a mass with swordsmen at the front covered by spearmen in the second rank, and another line of spears in reserve. There is nothing here to contradict Cruickshank’s interpretation that these men are intended to be Ecgfrith’s Saxons and Bridei’s Picts fighting it out. The fallen figure is probably meant to be Ecgfrith himself.The carrion-bird, probably a crow or a raven, reminds us of the war-poem of Brunanburh with its ‘horn-beaked raven with dusky plumage’ enjoying the feast of the battle-dead.

If we accept that the Aberlemno Stone as an accurate portrayal of the fighting men of Dunnichen, then it should contain clues to the battle. Its most surprising revelation is that at least some of Ecgfrith’s men fought on horseback. This turns on its head the traditional view that, while the Saxons might ride to the battlefield, they always fought on foot. This tradition may however date from later times when the bulk of Saxon armies were made up of the fyrd, county levies who in most cases would not have been able to afford to own a war-horse. Judging from Stephan’s account of the Two Rivers campaign, Ecgfrith’s northern expeditions were well-mounted and presumably capable of fighting on horseback when the occasion demanded.

Was Dunnichen, then, a cavalry charge against infantry? The stone certainly gives a sense of horses galloping towards the enemy, and of the foot-soldiers braced to resist with spears or pikes, much as the men of Robert the Bruce did at Bannockburn. Bridei evidently had horsemen of his own which, to judge from the final scene on the stone, he kept back for a perhaps decisive sortie once the English efforts to break the line ran out of steam. The Battle of Dunnichen was not one of those battles that went on all day. According to the anonymous monk of Lindisfarne, it began at the ninth hour, that is, at three o’clock in the afternoon (the remarkable precision about the time suggests that our monk had heard it from an eye-witness). Perhaps Ecgfrith had staked the outcome on a glorious charge straight at the enemy. More likely, as an intelligent if impetuous king, he would have tried hit-and-run tactics that worked so well for Duke William at Hastings. Probably he was overcome by sheer force of numbers. A timely sortie from Bridei’s horse might have hemmed the English in at the bottom of the hill on their exhausted mounts. Floundering in the mud by the lake-side, the king ‘and a great part of his soldiers’ were cut down one by one by Bridei’s lightly armed militia. Ecgfrith was probably among the last to fall, his bodyguard lying dead around him, true to their oaths. Not all the English were slain. Some were captured and taken into servitude, and at least a few escaped and returned to England. St Cuthbert, then at Carlisle, heard of ‘the woeful disaster’ within a few days.22

Given the likely odds, one might wonder why Ecgfrith accepted battle, when, with his mounted equitates, he might easily have made a tactical retreat. In war-games, even when the forces are fairly evenly matched at three Saxons to four Picts, Ecgfrith tends to do badly. The best Guy Halsall playing Ecgfrith could manage was to extricate the English army from a hopeless position.23 But perhaps, as Fraser suggests, the option of retreat was not really open to the Saxon king. Loss of face could have fatal consequences. Although Ecgfrith may not have been expecting to fight a pitched battle, he may have welcomed the opportunity to achieve a swift and spectacular victory. What he might have overlooked was the ability of the formidable Bridei to transform the Picts from the disunited tribes of the 670s to a united kingdom with shared goals and common purpose: something close, perhaps, to a sense of national identity.

We are told more about the reactions to the news of the battle than about the battle itself. According to the monk of Lindisfarne, St Cuthbert had predicted the death of King Ecgfrith twelve months before the battle.24 At the actual moment of the battle, Cuthbert was in Carlisle admiring the city walls and ‘the well built in a wonderful manner by the Romans’. Suddenly the holy bishop paused for a moment with downcast eyes, leaning on his staff. Then, raising his eyes heavenwards he cried out with a groan,‘O O O! I think that a battle is over and that judgement has been given against our people in the war.’And so of course it proved when, a few days later, ‘it was announced far and wide that a wretched and mournful battle had taken place at the very day and hour in which it had been revealed to him’.25

Despite Ecgfrith’s shortcomings, Cuthbert was obviously grieved at his death. Cuthbert’s brother bishop Wilfrid, who had fallen foul of the king, was less charitable. While celebrating Mass he is said to have had a vision of a headless Ecgfrith falling, and his soul being dragged off to hell by a pair of demons, ‘sighing with a terrible groan’.26 What may have been another portent is recorded in the Anglo-Saxon ‘F’ Chronicle. In the year 685, it says, ‘it rained blood and milk and butter was turned into blood’. Red rain is a rare but genuine phenomenon, apparently caused by tiny marine algae. Presumably it was held to foretell bloody events, though, unfortunately for that theory, this particular chronicle doesn’t mention the battle at all!

There is also a reaction from the opposite perspective preserved in the Irish annals in the form of a poem, the Inui Feras Bruide Cath,attributed to a Riaguil of Bangor. In James Fraser’s translation, the relevant lines run as follows:

Today the son of Oswy was slain

In battle against iron swords;

Even though he did penance,

It was penance too late,

Today the son of Oswy was slain

Who was wont to have dark drinks;

Christ has heard our prayer

That Bridei would avenge Brega.

Like Cuthbert, the poet attributes Ecgfrith’s destruction to his predations in Brega the previous year. Evidently the king repented what had been done there, but repentance did not save him. The relevance of ‘the dark drinks’ is obscure, but it is clearly part of the imagery of doom.27

Symeon of Durham preserved a story that Ecgfrith’s remains were taken across Scotland for burial at St Columba’s foundation on Iona, known by the Irish annalists as theisland of Hi. One possible reason for so surprising a resting place is that Ecgfrith’s brother and successor as king, Aldfrith, had, like Oswald, been a monk at Iona. However, it is more likely that the royal remains would have been claimed by the Abbey of Whitby where Ecgfrith’s father Oswy lay among other members of the family. Whatever the truth of the matter, the evident respect shown to the dead king can only be because both sides at Dunnichen were Christians. As we have seen, the pagan Penda mutilated and dishonoured the bodies of Kings Oswald and Edwin,as the pagan Vikings were to do to the ninth-century Saxon Kings Aelle and Edmund. Christian kings still had no compunction about killing one another, but mocking a man’s soul after death was a different matter.

The news of the battle and the death of the king with most of his following was clearly a shock for the English. Kings had been killed in battle before, but never against northern tribesmen. The event was sensational enough to be recorded in the English, Scottish and Irish annals, and has even been called the best recorded episode in Pictish history.28 Dunnichen was a famous battle, but was it a decisive one? Bede certainly thought so. From this point on, he wrote, quoting Virgil for an appropriate phrase, the hopes and strengths of the Anglian kingdom ‘began to ebb and fall away’.29 The Picts drove out or enslaved the English settlers north of the Forth, and sent Bishop Trumwine packing. The fall-out spread to the Scots of Dal Riata and the Britons of Strathclyde, who recovered the liberty they had lost under Oswy and Ecgfrith. The compiler of the Historia Brittonum agreed: ‘the Picts with their king emerged as victors, and the Saxon thugs never grew thence to exact tribute from the Picts’.

These judgements have led some historians to regard Dunnichen as ‘among the great and decisive battles of Scotland’30 and even ‘the first battle of Scottish Independence’.31 It may be, however, that Saxon power in the area was already waning before Ecgfrith rode to his doom at Dunnichen. Bede includes the earlier seventh-century Kings Edwin, Oswald and Oswy among his bretwaldas, but significantly not Ecgfrith. The real turning-point, as Fraser suggests, may have been the Battle of the Trent in 679, when Ecgfrith was heavily defeated by the Mercians. While Bede’s view cannot be dismissed lightly, since here he was reporting events from his own lifetime, there were at least two more clashes between Northumbrians and Picts in the Strathearn area in the opening years of the next century, in which the former devastated lands as far north as Strathtay. Dunnichen may, Fraser argues, have only seemed decisive in retrospect. The immediate effect of the battle was the succession of the childless Ecgfrith by his scholarly and more peacefully inclined brother Aldfrith. Aldfrith was in turn succeeded by his son, Osred, but within a generation Osred was assassinated and the dynasty of the house of Aethelfrith, the kings of Northumbrian greatness, brought to an inglorious end. Looking back, some may have seen Dunnichen as marking the beginning of the end.

At any rate, Dunnichen has become the most famous of all the Dark Age battles fought in the north. It helps that we know roughly where and exactly when the battle took place.The1,300th anniversary of the battle, and, still more, the identification of the Aberlemno Stone by Graeme Cruickshank as a unique Dark Age battle monument, caught the popular imagination. Hence, alone among pre-Conquest Scottish battlefields, Dunnichen is a listed battlefield. It already features prominently in a recent novel, Credo, by Melvin Bragg. It can surely be only a matter of time before someone turns it into a film.

The old ‘Wainwright battlefield’ and the new ‘Fraser variant’ lie within two miles of one another on opposite sides of Dunnichen Hill, a few miles ESE of Forfar (OS 1:50,000 map no. 54). The grid co-ordinates are approximately NO 515492 and 493511 respectively. A good starting-point is the churchyard in Dunnichen from where you have a view over the Wainwright battlefield and can imagine Ecgfrith’s men falling back in confusion towards the lake as they are enveloped by Pictish warriors pouring down the slope of Dunnichen Hill. Although nothing now remains of the original lake, or even the bog that replaced it, a pond dug to attract wild duck in the 1990s does at least mark its approximate centre. The monument to the battle, unveiled in 1985, stands nearby, along with a cast of the Dunnichen Stone, a slab inscribed with Pictish symbols. Although the stone could be roughly contemporaneous with the battle, it has no obvious connection with it. The original is now on display at the Meffan Institute in Forfar. In 1998 a new cairn commemorating the battle was raised by the footpath between Dunnichen and the neighbouring village of Letham, closer to the centre of the Wainwright battlefield. It is dedicated to the memory of the late Scott Kidd who led the fight to save Dunnichen Hill from quarrying in the 1990s (see below).

Next the visitor should ascend Dunnichen Hill via the minor road and then the track that lead to the summit. On a clear day there is a grand view southwards over the Wainwright battlefield of crop fields and pasture, and beyond over the hills, vales and scattered woods eastwards of the Sidlaw Hills. The hill was once crowned By a stone rampart that may have fromed part of the defences of the original dun Unfortunately it was destroyed in the nineteenth century to provide material for stone walls. In 1947 Wainwright found a ‘broken line of what seems to be a stone wall or earthwork’ which he thought worthy of further investigation (but has not, so far, received any).This was probably the same grassy terrace with scattered rocks that I remember from a visit to the battlefield in 1983. Unfortunately a communications mast has since disturbed the hill-top, and in 1991 the entire hill was threatened when a company applied for planning permission to remove 4.5 million tonnes of andesite stone from its vicinity over thirty years. The application was objected to by historians from all over Scotland and beyond, on the grounds that it would ‘destroy the visual explanation for Bridei’s battle strategy’,32 not to mention any possible remaining archaeological evidence. The application was withdrawn, but the threat remains. On the more positive side, the Save Dunnichen Hill campaign drew attention not only to the importance of the Battle of Dunnichen but to Scottish battlefields more generally.

New monument to the battle raised on the northern shore of the lost lake where Ecgfrith and his men fought to the death.

The Fraser battlefield is easily accessible as the A932 from Forfar passes straight over it in the vicinity of the farms of Foresterseat and Murton. From here you can see across Loch Fythie to the broach-tower of Restenneth Priory in the middle distance. Behind you lie the now wooded slopes of Dunnichen Hill, crowned by a communications mast, where Bridei’s men may have stood in spear-bristling lines, with Bridei himself at a command post further up with his small corps of mounted warriors. The priory ruins on their promontory on the north-western side of Loch Fythie by the B9113 are open to the public and are well worth visiting. Surprisingly the site seems never to have been investigated by archaeologists.

The Aberlemno Stone shows scenes of battle which match the events of Dunnichen. Could this be a genuine Dark Age war memorial?

Finally, one should seek the Aberlemno Stone in the kirkyard of Aberlemno just off the B9134 from Forfar to Brechin. The side showing the scene of battle faces eastwards towards the church, which can make photography awkward without artificial lights. Early in the morning is probably the best time. The whole area around Forfar is rich in Pictish antiquities, and a visit to the battlefield could form part of a fascinating Dark Age tour in a fascinating and surprisingly little-known area.