Prologue

THE CARRYING STREAM

The old songs were in our heads and hearts, like breathing, and were handed down through the generations in a living tradition, as if they had been carried along in a migration stream from across the sea.

—Jean Ritchie, Singing Family of the Cumberlands, 254

The clamor of worldwide music media and the identity-blurring effects of globalization—each dazzles our senses in the kaleidoscope of contemporary life. It becomes harder to hear clearly the notes ringing from Jean Ritchie’s “old songs,” more difficult to see the light they beam into her “living tradition.” We must listen and look more carefully today for her family’s song stream, part of a remarkable diaspora: the great musical migration from Scotland, through Ulster, to Appalachia.

The story of our central characters unfolds over successive generations and journeys. As Scots in Ulster, then Ulster Scots in colonial America, they became known as the Scots-Irish, settling in and often moving on through Pennsylvania. Some then headed west, but many more followed the Great Wagon Road that started in Philadelphia and led them on through the Shenandoah valley of Virginia into the Carolina Piedmont and the Appalachian Mountains. Each stage of their pathway represented a life-changing and sometimes harrowing episode for the migrants.

This journey is vividly expressed in their songs: laments and emigration ballads for leaving; lively dance tunes for traveling; homesick and hopeful songs upon arrival; and finally, new songs and sounds that emerged as cherished ballads adapted to new lifestyles in an adopted land. Though these songs and the traditions that birthed them reveal many stories, here we chart their imprint along a particular route. Marking the verse and fiddle footfalls, we explore the influences they embraced and consider the lasting impact of it all on contemporary music.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott, and Francis James Child had already demonstrated the worth of collecting and cataloging music from folk traditions, preserving hundreds of ballads and songs for posterity. The musical legacy of the Scots-Irish may have been reshaped in the New World, but its heart and soul was captured by nineteenth-century collectors—the “songcatchers”—working in the more-isolated settlement areas of the southern Appalachians. At times, they followed an idealized agenda to be sure. Convinced that the remoteness of some communities had preserved a cultural purity, they took steps in their collecting to guarantee they found just that, often sidelining young, “impressionable” singers in favor of older “source” balladeers and largely overlooking any African influences on the music they uncovered. Still, their work was pioneering in its day and offers something of a guiding light to this book. The “Minstrel of the Mountains,” Bascom Lamar Lunsford of Madison and Buncombe Counties in western North Carolina, was an accomplished musician who collected and preserved over 3,000 songs, tunes, square-dance calls, and stories that might otherwise have been lost to history. He held a romanticized reverence for the ancestry of the music and those who came before him, as he expressed on May 22, 1948, in the Asheville Citizen:

“Yes sir,” he would say, after a fiddle tune had been finished. “Your great-great-great-grandpappy might have played the same tune in the court of Queen Elizabeth.” Then he would tell them how the songs and square dances came straight from the jigs, reels and hornpipes of Scotland, Ireland and England, trying to show that though the words had changed from country to country and generation to generation, even from valley to valley in the same range of hills, the essence of the music changed not at all. It formed a link, unbroken, back through time, tying them to the past.1

An Appalachian farm. (Courtesy of Amy White/Al Petteway)

Rooted mostly in the rolling hills of Scotland and Ireland, this music spread along the boughs and branches of a family tree of songs, reaching into the shady wooded groves of the southern Appalachians. It had flowed into the New World along what Scottish poet, songwriter, and folklorist Hamish Henderson so memorably called a “carrying stream.” This current was prone to meander along its winding course, and as song collector and scholar John Moulden observed, a song might settle in a mountain hollow as “the end result of an unknown series of passages and re-passages of the Atlantic, the North Channel or the Irish Sea . . . and some versions could have started in Scotland, some in Ireland, and some could have been lurking in New England since being imported on ballad sheets.”2

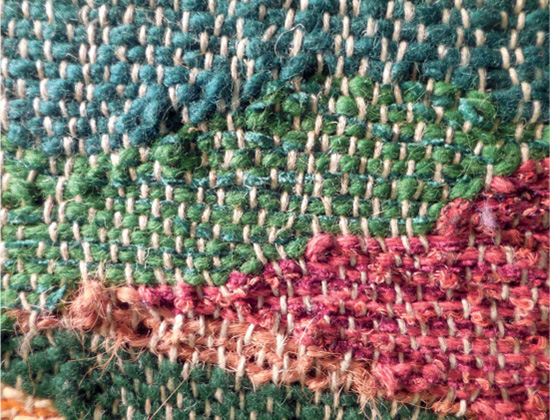

Along the way, the Scots-Irish brought their fiddles and jaw harps, adopting the lap dulcimer and, of course, carrying their cache of beloved songs. Old ballads and fiddle tunes were adapted to their new landscape. For those hardy settlers moving into the mountains, the isolated coves were a natural habitat for their evolving customs, vernacular, and music. Old World oral tradition ensured these were conscientiously handed down; New World encounters enlivened the repertoire with fresh ideas and influences. Stories and songs reflected another inheritance running through the Scots-Irish temperament: a deep longing for an old country far away across a half-forgotten sea, balanced all the while by devotion to their adopted home place in the deep recesses of the Appalachian mountain valleys. Music, as ever, provided the social fabric, creating a sense of community amid isolation and reinforcing identity. That said, while the Scots-Irish origin is clearly the dominant one, it is the braiding and weaving of European, African, and indigenous American influences that creates the unique tapestry of Appalachian music. Extract any one of the essential threads—Scots-Irish, English, German, French, African American, Cherokee—and the pattern is lost.

They were a man’s words, a ballad of an old time

Sung among green blades, whistled atop a hill.

They were words lost to any page, tender and fierce,

And quiet and final, and quartered in a rhyme.

This was a man’s song, a ballad of ridge and hound,

Of love and loss. The words blossomed in the throat.

This was a man’s singing along behind his plow

With a bird’s excellence, a man’s shagbark sound.

—James Still, “Ballad”3

Over time, details may blur and voices fade in the stories we hold and share. When our own tales pass from individual living anecdotes into collective memory, the characters, places, and distinctive voices become hazier still. Perhaps then, for some, books are primarily a place where traditions can be recorded and preserved, a repository for things “as they were.” For us, however, the musical migrations described in Wayfaring Strangers live and breathe. They are best experienced through today’s tradition bearers and the music they share. This is why it was fundamental to our book that their voices speak through its pages. They have a story to tell that illuminates the gray journals of history with a warm, living flame. You will not hear them claim that their forebears alone laid the foundation stones of country music or rock and roll, as if such clear-cut lineage can ever be established; they are simply immersed in Hamish Henderson’s “carrying stream.” Today’s performers and raconteurs are included to highlight the sheer vibrancy, the “living tradition” of this musical culture. For this is the key to its irresistible appeal and the enduring curiosity about its history.

Tapestry woven by Barbara Grinnell. (Collection of Darcy and Doug Orr; photograph courtesy of Karen Holbert)

Shawl. (Collection of Darcy and Doug Orr; photograph courtesy of Karen Holbert)

So Wayfaring Strangers features the words of revered tradition bearers who have personal stories to tell and professional insight to share. These include Appalachian singer and dulcimer player Jean Ritchie, who as a young woman visited Scotland and Ireland on a Fulbright Scholarship to trace the roots of her family’s songs; Ron Pen, University of Kentucky folklorist and shape-note singer; Alan Jabbour, retired head of the Folk Life Division of the Library of Congress and a longtime fiddle player and scholar of the music; and Sheila Kay Adams, seventh-generation Appalachian ballad singer, musician, and storyteller from North Carolina who in 2013 was recognized as a National Heritage Fellow. Members of the Seeger family share their wisdom, including Pete, the legendary folk songwriter and grassroots campaigner, and Mike, folklorist and traditional roots-music preservationist. For many years, Grammy Award–winning multi-instrumentalist and song collector David Holt partnered with Doc Watson, North Carolina’s flat-picking guitar master; both add their perspectives on the music. A host of their Scottish and Irish counterparts share the view from the other shore, including Archie Fisher, Jean Redpath, John Purser, Jack Beck, Brian McNeill, Cara Dillon, John Doyle, and Len Graham.

Many of the world’s cultures share the concept of diaspora as part of their national identity. By choice or coercion, their pioneering forebears endured life-changing relocations, carrying songs, dances, stories, and other priceless traditional arts to the far corners of the globe. And on it goes up to the present day. Wayfaring Strangers provides a metaphor, in this respect, for other musical migrations. At some point in life’s journey, each of us longs to find our way back “home,” and as such, this book may be a welcome companion for many a wayfarer. In this role, the following pages do not seek to offer a new angle on the historic backstory. Indeed, the Scots-Irish migration narrative has been revisited many times as a core tale of American history and culture. How it has usually been told, however, is in itself quite curious. Generations of texts on the story of the Scots-Irish begin in the early seventeenth century, yet movements of people between Scotland and Ireland can be traced back to 8000 B.c. So there really is no starting point; this is a story joined in progress. Likewise, Scots-Irish settlement in the United States is heavily chronicled as an eighteenth-century event, petering out after the American Revolution. If pinpointing a start constrains the story, setting an end point is just as unrealistic. Far from fading out in the mists of time, this narrative flows on as part of an epic migration saga that saw 50 million souls cross the ocean from Europe in the nineteenth century. Emigration is a perpetual chain, each migrant adding a unique link to its infinite length. So the Scots-Irish story is, above all, part of a wider American and even human experience, and that underpins what we seek to chronicle.

To grasp the full scope of this exodus and the effects on its living musical soundtrack, we will follow a twisting trail through discrete stages of our migration story. The first stage, “Beginnings,” traces the antiquity of musical traditions to troubadour and minstrel balladry and through people and regions of extraordinary musical influence in Scotland. “Voyage,” the next stage, considers millennia of seafaring exchanges between Scotland and Ulster that are concentrated into a planned resettlement scheme, a catalyst for the evolving music traditions of Ulster Scots, leading to yet another epic farewell with songs of parting and emigration. Our story then follows a long and traumatic crossing of the Atlantic “Sea of Green Darkness” in the age of sail, during which the music persisted in their daily lives. Near the end of their transatlantic journey, these wayfarers must reinvent themselves and bring their music to yet another shore, a new horizon of the promised “Canaan’s Land.” Finally, in “Singing a New Song,” we consider how these wayfarers, now at least twice transplanted, express a deep-rooted migratory nature and move on once again to meet and mingle with other cultures, shaping and enriching their music.

Basket. (Collection of Darcy and Doug Orr; photograph courtesy of Karen Holbert)

After you emerge from this book, resolve to lay aside the words and meet the music in person. Then you will truly grasp its timeless essence and understand very plainly that, just as there is no true starting point, this is also a story to be continued.

The lovely past was not gone, it had just been shut up inside of a song, inside of a hundred songs. I knew that no matter how far apart we might settle the world over, that we’d still be the Ritchie Family as long as we lived and sang the same old songs, and that the songs would live as long as there was a family.4

—Jean Ritchie

Sunset on Loch Linnhe. (Courtesy of Ian MacRae Young, www.photographsofscotland.com)