Voyage

It was a’ for our rightfu’ king

We left fair Scotland’s strand

It was a’ for our rightfu’ king

That we e’er saw Irish land my dear

That we e’er saw Irish land.

—Robert Burns, “It Was a’ for Our Rightfu’ King” (CD TRACK 2)

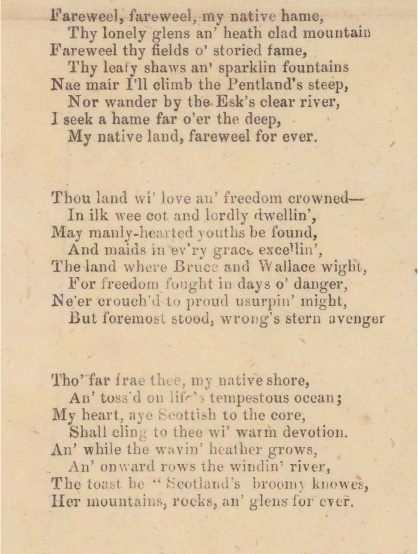

Farewell

With an eye on the next destination and a wayfaring tendency seemingly encoded in their DNA, Scots had been in a collective state of perpetual motion since the Middle Ages. In Britain and Europe, the prospect of adventure and opportunity sat eternally across the next horizon. By the seventeenth century, their gaze had turned westward across the North Channel to Ulster, where together they would write another chapter into their growing story of diffusion and diaspora. Their pattern of leave-taking may have had deep roots, yet there was a persistent tension between wanderlust and homesickness, retold in song and story over the generations from Scotland to Ulster to America. Robert Burns conveys the anguish of departure in “Farewell”:

Adieu! A heart-warm fond adieu;

Dear brothers of the mystic tie!

Ye favoured, enlightened few,

Companions of my social joy;

Tho’ I to foreign lands must hie,

Pursing fortune’s slidd’ry ba’;

With melting heart, and brimful eye,

I’ll mind you still, tho far awa’.

OVER THE SEA TO ULSTER

For the ancient maritime communities around the North Channel of the Irish Sea, the water was more a thoroughfare than a barrier. Land was impenetrable and, in places, densely wooded, so the sea was the way. Coastal migrations were the essence of life, and the North Channel was actively navigated in both directions throughout time: the first post-Ice Age crossings by Stone Age people from Scotland to Ireland over 8,000 years ago; Saint Ninian’s fifth-century outposts and early mission work to convert the Picts;1 Saint Columba’s epic voyage in the sixth century, crossing from Antrim to Galloway in a flimsy leather currach and succeeding with Christianity where Rome’s military conquest had failed;2 seafaring raiders (“Scotti” or “Scoti” as the Romans named them) colonizing western Scotland from Ireland; the Galloglaigh and the Redshanks, mercenary soldiers of the Middle Ages recruited from the Scottish Highlands and the Hebrides to fight for Irish chieftains. Foremost among these warriors were the MacDonnells of the Scottish Isles and Antrim. They were part of the branch of the Dàl Riata (Dalriada), a dynasty that established itself in modern-day Argyll and the Inner Hebrides, perhaps driven to spread from Ireland to Scotland as a result of successional tensions. Indeed, while Lowland Scots have always been linked with Ulster migrations, innumerable Highland Scots moved to Ulster’s Glens of Antrim between 1400 and 1700. Their settlement, along with Lowland Scots’ influence, helped shape Ulster’s language, music, and folkways.

The MacDonnells managed to create and command a sphere of influence that spanned the North Channel, drawing in eastern Ulster and parts of western Scotland under a single rule.3 By 1530 they oversaw the territory as a cross-channel cultural domain. The ancient Scots Gaelic lullaby “Bidh Clann Ulaidh,” (The Children of Ulster) emphasizes the connection. As well as the king’s family, the mother sings her guest list of Scottish clansfolk that will attend her baby daughter’s future wedding: the MacDonalds, the MacAulays, the MacK-enzies will all be there. Pride of place, named first, are the guests who will sail across the North Channel to come to the festivities.

Bidh Clann Ulaidh, luaidh’s a lurain

(The Clans of Ulster, my darling, my treasure)

Bidh Clann Ulaidh air do bhanais

(The Clans of Ulster will be at your wedding)

Bidh Clann Ulaidh, luaidh’s a lurain

(The Clans of Ulster, my darling, my treasure)

Dèanamh an danns air do bhanais

(Will be dancing at your wedding)

—“Bidh Clann Ulaidh”

The sea separation is so narrow that there are numerous places on the Ulster coast where the southwest of Scotland is easily visible on the horizon. Coastal villages on either side were connected by route ways well known to the seafarers of the day, who worked their way toward their destinations by relying on visual memories of rocky islets, coastal inlets, and a keen sense of direction. Mediterranean mariners had access to detailed harbor books of their ports of call, coastal maps, and travel time between ports; it was a body of information developed and shared between Venetian, Genoese, and Catalonian draftsmen. Setting sail across the North Channel was never so straightforward, and points of embarkation had to be picked very carefully. The Irish Sea can whip up a squall in a matter of minutes, and small vessels would have been easily endangered, as they are today.4 The small harbor town of Portpatrick on the Rhinns of Galloway Peninsula in Scotland has a natural harbor and a name that proclaims its historical role as a port of transportation to and from Donaghadee in Ulster. This crossing is a distance of only twenty-one miles—in fair weather a relatively easy voyage in either direction. Depending on the wind, weather, and sturdiness of craft, travel time could range widely from three to twelve hours. As emigration and trade from Scotland grew through the centuries, a whole assortment of materials might accompany the voyage, including grains, cattle, textiles, and mail. In time, it became feasible for friends to pay each other visits by crossing such channel routes.5

View from Scotland over the sea to Ulster. (Photograph by Doug Orr)

Ancient Seafarers and Channel Crossers

Dr. John Purser, Scottish composer, musicologist, and music historian; interviewed in Dunkeld, Scotland, June 2011, by Fiona Ritchie en route to the National Museum of Scotland.

Take things like, of course, the Sea Shanties. Ah, now, here’s a wonderful example in Wedderburn’s “The Complaynt of Scotland,” which is in 1549 that he writes this. And, poor devil, he’d had his house burnt down in Dundee by the English, and he’d moved down into Fife, and he’s grumbling away, “The Complaynt of Scotland,” you know, you can just see him, dipping his pen into the ink well of his thoughts, brutal, bitter thoughts, you know, writing down. And then he thinks, “But Scotland is so wonderful, and we have this wonderful music and all of these tunes,” and then he gives this huge list of tunes and dances. And then later he goes on, and he describes coming down towards a port, and the sailors are getting ready to sail in a big sailing ship and he has all their cries. And there’s about half a dozen different languages in there in 1547, and it’s just this extraordinary macaronic kind of splurge of sounds, almost half of it is very hard to make out what is meant because, you know, “Sarabossa! Sarabossa!” What the hell does that mean? I haven’t a clue. It’s some Portuguese or Spanish thing that they’re shouting. It will be a little group of sailors on the ship that handle one particular capstan or something like that. But this has ended up in a Scottish manuscript in 1547.

Well, if you’re taken right back to the Stone Age, you can see right up the western seaboard of Europe—from Brittany, Cornwall, Wales, Ireland, parts of England, Scotland, Scandinavia—these huge henges: monolithic structures and burial graves, burial mounds, and so on. Now there are big regional variations, but they are clearly part of the same culture, overall it is a western European seaboard culture, and these guys are moving around. And then when you get to the Bronze Age, you’ve got the Phoenicians coming out, the Flying Tin Men as they were called, coming to Cornwall, which had a big supply of tin. But they’ re also looking for copper, you know, after Santorini [the volcanic Greek island] blew up, you see, that suddenly screwed up copper supplies. Now these skills in handling rock and turning it into metal are these styles, and technologies are spreading right up and, indeed, possibly down the west coast.

Take the Bronze Age horns in Ireland—well, mostly in Ireland, one found in Scotland, one down in England—but the manner of working bronze from the bronze smiths of that period in Ireland is the same as the bronze smiths in Orkney and Shetland at the same time. So these boys, you know, the experts are running up and down the coast, and so yes, these influences can be very widespread. People were more mobile than you might imagine, or at least the people with technological skills were certainly mobile, and you could say the upwardly mobile people—musicians tend to be mobile, a long, long tradition of traveling musicians, and I mean, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose, you know? If you want to be a Scottish musician, why not just go to America or Germany, where they might even pay you?

Possession of a boat and the ability to handle it across the North Channel, you know, you can’t just be anybody to be able to do that. The saints that came over from Ireland, and anybody who was remotely holy was a saint, these were all upper-class people, you know, Saint Columba and his followers, they all came from aristocratic families, which is how they were able, to a degree, to take over, when Dál Riata [Dalriada] became a kingdom across the North Channel, in fact, the Scottish end of it became bigger than the Irish side of it eventually. And, yes, at the same time, there would be people that scarcely ever moved. Just as there still are, I mean, my neighbor, Katy Mary, had never been out of Scotland until her son got married in New York, and she’s never been on the European Continent, and she’s very rarely left [the Isle of] Skye. She started off on Harris [in the Outer Hebrides], and coming to Skye was quite enough [laughing].

And if you look particularly at the clarsach [harp], the Scottish clarsairs [harpers] were always going over to Ireland and getting an education there as often as not, sometimes getting their harps made from there, sometimes they were made in Scotland. The so-called “Brian Boru” harp was almost certainly made in Scotland. That went right on into the nineteenth century, there’s a photograph of one of them [Patrick Byrne], a Hill and Adamson photograph, wonderful one. And he’s in a sort of Bardic robe with his harp and his Bardic pose—it’s a great picture. But he would be one of the last examples of a traveling harper.

Map of the Province of Ulster, 1676. (Mapmaker, John Speed; courtesy © Antiquarian Images/Mary Evans Picture Library)

The connections between Scotland and Ireland were forever altered by the Plantation scheme of King James VI and I. The idea was not new; the Glens of Antrim, with their close proximity to Scotland and long history of clan intermarriage, were the setting in 1380 for Clan Donald establishing a strong foothold of Scots. In that year, John Mor MacDonnell of Islay in the Hebrides became the first of the MacDonnells of Antrim to build castles at Battlecastle, Red Bay, and Glenarm in Ulster. Their headquarters was the fortress of Dunluce Castle, sitting atop a rocky outcrop and surrounded by sea on three sides. Today, the farmland around the rock is littered with lumps and bumps, remnants of a lost settlement. When archaeologists lifted the sod in 2011, they exposed a well-preserved seventeenth-century Scottish townscape with cobbled streets and merchants’ houses laid out on a grid—all indications of the significant trading post built there by Randall MacDonnell, the first earl of Antrim. Dunluce was attacked and set ablaze during an Irish rebellion in 1641, after which many settlers returned home to Scotland and the town was abandoned. Archaeologists continue to unearth many artifacts, and, as the remaining 95 percent of the town is carefully excavated, they will uncover the material story of the early Scottish settlements of Ulster.

The principle of “planting” peoples on Irish land started with Henry VIII in 1541. In 1556 Queen Mary authorized a similar scheme in southern parts of Ireland, and her policy of land grants to English landlords persisted under Elizabeth I, with limited success. James Hamilton and Hugh Montgomery, two entrepreneurial Scots from Ayrshire, founded private Ulster enterprises in 1606. The focus of their settlement projects were Antrim and Down, the two counties closest to Scotland. Both allies of King James I, Hamilton and Montgomery offered cheap rents to attract new tenants across the water. In May 1606 the first boatloads of Lowland Scottish (almost entirely Presbyterian) settlers arrived to take up tenancy on the Hamilton and Montgomery estates. There, they established the first permanent settlement of “Ulster Scots”; today’s descendants of Sir James Hamilton (the Rowan-Hamilton family) and Sir Hugh Montgomery (the Montgomeries of Greyabbey) still live in the area.

Ulster and Scotland: An Ancient Link

Len Graham, Irish traditional singer and song collector; interviewed in Swannanoa, North Carolina, July 2013, by Fiona Ritchie and Doug Orr during Traditional Song Week at the Swannanoa Gathering folk arts workshops.

Common language, common culture, the whole fiddle tradition and the whole music tradition is all very, very similar and connected. The history and the geography have all played a part in it. You know the shamrock, the rose, and the thistle, meaning the three—England, Scotland, and Ireland—all contribute to what we now call the Ulster song tradition, or Ulster music tradition for that matter. And you know, you’ve got the bagpipes, which are common to both Ireland and Scotland. It became popular with the British regiment, you know, Scottish and Irish regiments, in the nineteenth century, but it was a common instrument in both countries. The harp, of course, is common to both Ireland and Scotland. The fiddle is most popular by far in Scotland and Ireland [with] traditional musicians. And then the songs reflect that as well. You’ve got songs that have got definite Scottish origins but with very much an Ulster or a northern dialect or accent. And you find that goes two ways. One of the early songs that I would have heard from my grandmother, and it also turns up in Kintyre [Scotland] about a shipwreck, the Enterprise, that went down in 1834. So that song turns up and was collected by Hamish Henderson in Campbeltown in that area of Argyllshire, and also I got the same song because that distance is so close—twelve miles—and the ship had gone down between the two. So the song turns up in both camps. There’s those connections, but there’s much more than that: the history, the language, the Irish language, the Gaelic language, as you call it in Scotland, was spoken. So there’s a long association between the two countries.

North Channel Crossing Points

The success of the 1606 Hamilton and Montgomery settlement secured the foothold that facilitated the Plantation of Ulster, launched by King James in 1610. It also emboldened James with his Virginia colony, and in 1607 the first English settlers arrived in Jamestown. With the “Dawn of the Ulster Scots,” the Ulster Scots-American connection was also born.

The Scots were “a people on the move.” As the seventeenth century began, their population was increasing, and there was a surplus of young men seeking employment and adventure overseas, not only in Ulster. In fact, during the early part of the seventeenth century, Scots were more likely to emigrate to Scandinavia and Poland than to Ireland. The period was, nevertheless, marked by periodic waves of Scottish emigration over the sea to Ulster, especially through the ports of Carrickfergus and Derry-Londonderry. The Scottish famine years of the 1690s unleashed an exodus of tens of thousands, at which time the Scots became a majority community in the province of Ulster.

THE ULSTER SCOTS

The rose of all the world is not for me.

I want for my part

Only the little white rose of Scotland

That smells sharp and sweet—and breaks the heart.

—Hugh MacDiarmid, “The Little White Rose”6

Scots in Ulster began settling into life in their new land, but the memories were still fresh of a home across the sea. The old life may have been tough and trying, but their urge to explore beyond the next horizon was tempered, as ever, with nostalgia for the place left behind. For some, the connections were restored by occasional return visits to see family and friends. The majority never again set foot on their ancestral land, however, which gradually receded into folk memory. Some who left were missed eternally by those they left behind. In the Hebridean song “Dh’fhalbh Mo Nighean Chruinn Donn” (My Lovely Brown-Haired Girl Has Gone), a man sings in Scots Gaelic of his lost love, gone to live in Newry, near the Mountains of Mourne.

Dh’fhalbh mo nighean chruinn donn (My lovely brown-haired girl)

Bhuam do’n Iùraidh (Has gone from me to Newry)

Dh’fhalbh mo nighean chruinn donn (My lovely brown-haired girl)

Cneas mar eal’ air bhàrr thonn (Her breast as white as the swan on the waves)

Och ’s och, mo nighean chruinn donn (Oh, my brown-haired girl)

A dh’fhàg mi-shunnd orm (You have left me unhappy)

She may have married for better prospects in Ulster, but sorrow lingers on both shores.

Ged tha thusa an drasd’ (Although you are now)

Ann an Gleann Iùraidh (In a glen in Newry)

Ged that thus’ ann an tàmh (Although you are dwelling there)

Tha t’aigne fo phràmh (Your mind is sorrowful)

Agus mise gun stàth (And I am without purpose)

Le do gràdh ciùrrte (With the pain of your love) (CD TRACK 3)

As the Plantation plan proceeded into the seventeenth century, many more families began making the journey toward resettlement in Ulster. The majority of the Scottish emigrants entered this new colony as landless tenants. They would rent from a class of principal landowners called “undertakers” These English and Scots settlers received up to 2,000 acres and were required at their own expense to settle ten Scottish or English families for each 1,000 acres. Other designated landowners were the “servitors,” administrative and military men who were granted Ulster estates from the government in London.

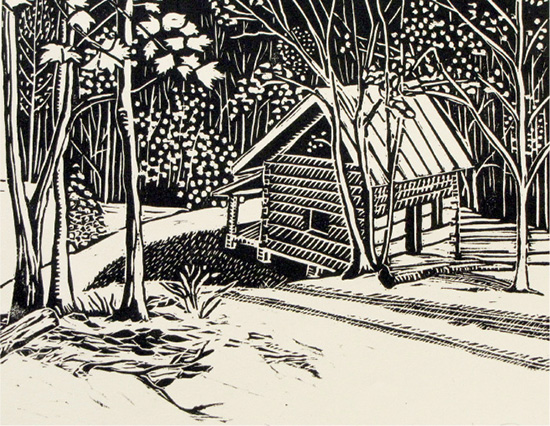

Ulster Cottage. (Woodcut; courtesy of Declan Forde)

Belfast to London was over 460 miles by land and sea, and the region was undeveloped, underpopulated and noncompliant to English rule. So the Ulster Plantation, Ireland’s largest, was a high priority for colonization. During much of the seventeenth century, rents were low and land abundant, fostering a steady stream of immigration into the colony. The year after the King James Plantation era was launched, approximately 8,000 new families had settled into the six official Plantation counties: Armagh, Cavan, Donegal, Fermanagh, Londonderry, and Tyrone. Antrim and Down, the coastal stretches of East Ulster with closest proximity to Scotland, had been part of the original private Plantation plan, and they continued to absorb the largest number of Scottish settlers.

Scots settlers were more accustomed to difficult living conditions and humble means than their English Plantation neighbors. More restless by nature, too, they were prone to relocate in search of better farmland. The largely rural culture best supported the small individual agricultural settlement called a “clachan,” which housed a cluster of cottages whose tenants worked together on the surrounding land. Much smaller than the organized agricultural villages elsewhere in Europe, the clachan communities were less regulated, more self-sufficient, and only semipermanent. Yet there was a sense of neighborhood, ties of kinship and church, music gatherings (including songs from their Scottish background and Presbyterian Church hymns), and fairs and markets to bind the district together. These were key elements of a society that their descendants would later replicate in their southern Appalachian homesteads.7

The Province of Ulster is of special historic significance to both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, although today it has no official administrative or political status. Its name is derived from the Irish “Cuige Uladh,” which translated means “Fifth of the Ulaidh.” The Ulaidh were a collection of prehistoric tribes in the area, and the “fifth” refers to the five ancient regions of Ireland. Ulster evolved as one of Ireland’s four provinces, along with Leinster, Munster, and Connacht. Meath, originally the fifth province, was absorbed into Leinster, with smaller parts included in Ulster. The late Irish musician Tommy Makem composed the iconic ballad “Four Green Fields” to represent the shared essence of the four provinces, notwithstanding contemporary national boundaries and political divisions.

Historic Ulster comprised nine counties: Antrim, Armagh, Cavan, Donegal, Down, Fermanagh, Derry-Londonderry, Monaghan, and Tyrone. The 1920 Government of Ireland Act oversaw the partition of the island, with the Republic of Ireland established in the south and Northern Ireland created out of six Ulster counties (both sections remained part of the United Kingdom). Counties Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan were assigned to the newly independent Irish Free State, known today as the Republic of Ireland, with its capital in Dublin. Northern Ireland’s capital is Belfast, home of the Northern Ireland Assembly. This was established in 1998 by agreement of

political parties in Northern Ireland and the British and Irish governments and is the devolved legislature of Northern Ireland. The assembly is responsible for making laws regarding certain matters in Northern Ireland, with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland’s Parliament in London assuming designated government functions on behalf of all the constituent parts of the United Kingdom.

The partition of Ireland was calculated to place the Unionist counties (which had safe Protestant majorities) in Northern Ireland and the Roman Catholic counties in the Republic of Ireland. Today, however, Tyrone and Fermanagh have Catholic majorities, and slightly more than half of Northern Ireland’s 2 million people are Catholic. To this day, Antrim and Down, the two private Plantation counties that were resettled by Scottish landowners and are closest to Scotland, are the Irish counties with the largest percentage of Protestant citizens.

The ethnonationalistic conflict in Northern Ireland began with intensity in the 1960s but has deep roots in the area going back to King James’s seventeenth-century Plantation colonization. The 1998 Good Friday Agreement largely ended three decades of sectarian violence between Nationalist (Catholic) and Unionist (Protestant) paramilitaries. Political tensions between the once-bitter rivals have eased considerably, although the official peace has failed to eliminate conflict from the troubled housing estates of the Province, and sectarian rioting still erupts periodically. The two communities, separated in some parts of Belfast by “peace walls” work on jointly run programs to help children integrate across the historic divisions. The Good Friday Agreement also saw the establishment of the Ulster-Scots Agency (Tha Boord o Ulstèr-Scotch). Funded by government departments from north and south of the border, the agency supports the use of Ulster Scots or “Ullans” as a living language and promotes understanding of Ulster Scots history and culture.

The landscapes of Ulster are beautiful, from northwest coastal Donegal on the windswept shores of the Atlantic and the volcanic formations of the Giant’s Causeway on the northern coast to the scenic villages that rim the North Channel looking toward Scotland and Lough Neagh, the largest lake anywhere in Ireland or the United Kingdom. The capital of Northern Ireland, Belfast, is the country’s largest city, with a population of around half a million people. The university town is a historic center for shipbuilding, including the ill-fated RMS Titanic, constructed at the Harland and Wolff shipyard. The second-largest city in Northern Ireland is Derry, or Londonderry. Founded in the sixth century by Saint Colmcille (Columba), Derry was renamed Londonderry in 1613 upon receipt of its royal charter for King James I. The city’s name has always been contentious; today’s Catholic and Protestant communities have settled on a new name for the city, symbolized by its famous Peace Bridge across the River Foyle: Derry-Londonderry.

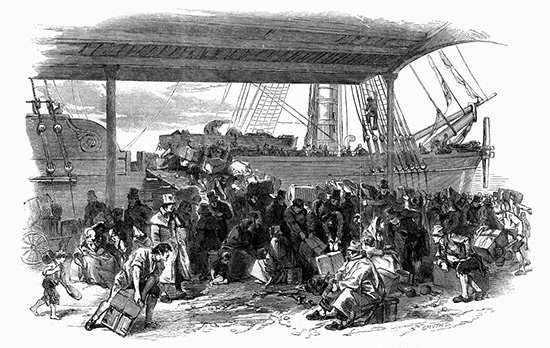

Lough Foyle was the most important embarkation port for eighteenth-century Ulster Scots’ emigration to America. Along with the familiar names of well-loved villages and counties, Northern Ireland’s two main cities are celebrated in many a traditional Ulster song—from the legacy of the early Scots to heartrending love ballads, American Wake songs, and the storytelling ballads that recorded personal tales of emigration across the Atlantic foam.

The Presbyterian faith of the Ulster Scots was a significant element of their lives and communities. The Plantation schematic was a complex cultural environment of three contrasting yet intermingling groups: Scottish Presbyterians, Irish Catholics, and English Anglicans. The original Plantation blueprint had been designed to deliver a controversial outcome: the displacement of the native Irish. The undertakers, which included land-owning Scots, were thus forbidden to lease land to Irish tenants. However, the reality of Plantation life caused theory and practice to differ; workers were needed on the farms, and the Scots leased land to Irish tenants from the outset, with the promise that they would not be deposed. There had, understandably, been considerable resentment by the Irish, who feared not just the loss of land to the settlers but also the depreciation of the old Gaelic order. Yet in the harsh reality of their existence, Scots and Irish lived amicably and worked side by side, and the government had to accept that it could not force the landowning undertakers to evict their Irish tenants. Consequently, a 1628 accord permitted the leasing of up to one-fourth of Plantation lands to the native Irish. Cordial and close interrelationships between the Scots and Irish were settled and accepted from then, transcending linguistic and religious differences. Seventeenth-century plantation life found its balance.8

I ONCE LOVED A LASS

Intermingling and Intermarriage

I once loved a lass and I loved her sae weel,

That I hated all others that spoke o’ her ill;

But noo she’s rewarded me weel for my love,

She has gone tae be wed tae another.

“I Once Loved a Lass” an old song of unrequited love with roots in Scottish and Irish balladry, embodies the melancholy sense of loss running through the heart of many a song and story: love lost through cultural, religious, and economic divides; family intervention; departures to foreign fields of work and war. The close-at-hand clachan communities of the Ulster Scots and their Irish neighbors must have presented opportunities for romance across the boundaries of class or church.

So this begs the question: with intermingling of the two cultures established, to what extent was there intermarriage? And in view of that, are the Scots-Irish in the United States of mixed Scots and Irish blood? Scholars have debated these questions and differ sharply. James Leyburn, in his landmark book, The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, addressed the issue from both sides, while admitting that no documentary evidence is available to settle the matter firmly.9

Only an examination of Ulster marriage records of the time could provide clear proof of intermarriage, but such documents do not exist. Circumstantial evidence of intermarriage is, however, quite significant. The communities shared bonds of language (a good percentage of early Presbyterian settlers were Gaelic speaking), work, and hardship, and—tellingly—they also shared family names. In the close-knit clachans, there is no doubt that some young people would have been moved more by romantic impulse than by religious loyalty. Surely, marriage and, as a consequence, religious conversion must occasionally have taken place.10

Leyburn is more persuaded that religion and pride of culture were significant deterrents to intermarriage. Irish Catholics and Scottish Presbyterians living their faith could each be zealous in their religious fervor. It was a passion that ran deep in the veins of Irish patriots in the long struggle for freedom from the English.11 Crossing the religious line beyond routine socializing was taboo and met with strong parental disapproval. In the tragic County Down ballad “Johnny Doyle” parents intervene between Catholic Johnny and his Protestant lover, and the girl’s family forces her to marry a boy of her own faith.

There’s one thing that grieves me and I must confess,

I go to meeting and my true love goes to mass,

But for to go to mass with him, I would count it no toil,

For to kneel at the altar, with young Johnny Doyle.

A horse and side-saddle, my father did provide,

With four and twenty horsemen to ride by my side,

Five hundred bright guineas, my father did provide,

The day that I was to be Sammy Moore’s bride.

Folding down the clothes, he found she was dead,

And Johnny Doyle’s handkerchief tied round her head,

Folding down the clothes, he found she was dead,

And a fountain of tears over her he did shed.

Over and above the religious boundaries, Leyburn contends that the depth of cultural pride, especially on the side of the Irish, was profound. If a marriage was made, Leyburn adds, it usually involved the Irish partner coming into the colonizing Scottish or English family.12 Others, such as Ulster scholar and musician Len Graham, take a broader view, citing the dynamics of substantial intermingling already mentioned and the evidence of merged Irish and Scottish surnames in America.13 Time may well have obscured any clear answer, but it is commonly accepted that there was a great deal of contact between the Ulster Scots and the Irish, whether at work or at social gatherings. The irrepressible nature of folk traditions suggests, at the very least, that some shared musical culture would surely have been woven among the communities.

Hearth scene at Ulster American Folk Park, Omagh, Northern Ireland. (Courtesy of Ian MacRae Young, www.photographsofscotland.com)

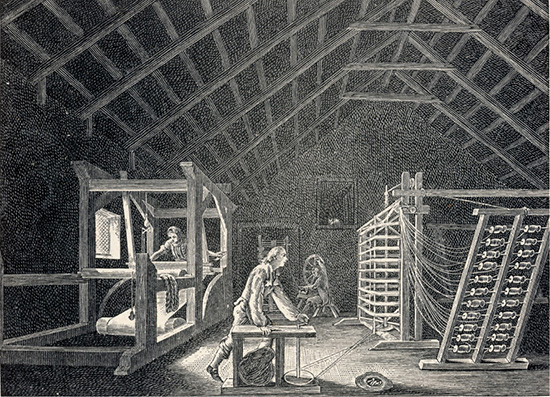

An assortment of threads and textures would have colored the musical fabric as smaller ethnic groups also came to Ulster, attracted by the linen industry—Welsh, French Huguenots, and English Plantation settlers among them, foreshadowing the later melting-pot scenario of the United States. Through the ages, traditional musicians have exhibited openness and a strong democratic streak, inviting a diversity of people and their music into the circle. No one person, or indeed any community, has ever been able to constrain the power of a song or a tune as a force for mutual understanding and shared joy.

ULSTER SONG

The Hearth and the Ceili

I am a rambling Irishman, in Ulster I was born in,

Many’s a happy hour I spent on the banks of sweet Lough Erne.

—“The Rambling Irishman” (CD TRACK 5)

Although the music of Ulster Scots bore an indelible imprint of the original Scottish immigrants, it steadily evolved beyond simply Scottish music now played in Ulster. Geography dictated the most obvious influences. Ulster place names, from Belfast and Derry-Londonderry to the River Foyle, appeared in the lyrics of many an Ulster refrain, and plenty of songs and instruments crossed back over the North Channel to Scotland. Other elements of Ulster Scots’ music bore the hallmark of the native Irish, and new compositions stemmed from the hybrid culture of thistle and shamrock. Wherever people gathered to sing or dance to a fiddle tune, the stage was set for the spark of something new. This might happen around the cottage hearth, at “ceili” gatherings (in Scotland, “ceilidh”), in music halls, and even at rural crossroads, where young people from a scattered community would unite at a midpoint on their country roads, a fiddle or accordion in hand to play for open air dancing. Since the church at the time frowned upon dancing, crossroads marked a safe haven for the musical fun. From Ulster to the Outer Hebrides, such scenes can be witnessed in paintings and old photographs; a single flute, an accordion, a fiddle, or a set of pipes is invariably in the frame, with the dancers evidently making the most of the experience. (Heavier road traffic, even in rural areas, brought the days of crossroad dancing to a close in the modern era.)

Nuala Kennedy, Irish singer, songwriter, and flute and whistle player; interviewed in Dunkeld, Scotland, June 2013, by Fiona Ritchie during Kennedy’s concert tour playing Irish and Appalachian music with A.J. Roach.

There is a good connection historically between the east coast of Ireland and Scotland because it is so close. Gerry O’Connor, a friend of mine and a fiddle player from Dundalk, he did some research into a manuscript: “The Donnellan Collection.” And we looked through that together, through all the tunes, and I recognized a lot of them (from living over here in Scotland) as Scottish pipe tunes. So there was obviously a lot of interchange musically between the east coast of Ireland and Scotland through the years.

You’re probably aware of a great record that was made a few years ago by Colum Sands and Maggie MacInnes, “Báta an tSìl” [CD track 3], about Newry in the north of Ireland, and how there were people coming from the Western Isles of Scotland and traveling down to the east coast of Ireland to the Newry area for marriage and for trade, so it seems like there’s a pretty strong connection.

I play in a band with Gerry called Oriela that plays the music of that area, which is the old Kingdom of Oriel (Airgíalla), which is an old division of Ireland around about the seventh century, and so the repertoire that we’re playing is local to that area. So it’s satisfying to me to have grown up in that area and come away and lived in Scotland and lived in America, but now to come back and explore my own native music again.

I came to Scotland to go to Edinburgh College of Art and came across some sessions and loved the atmosphere and the people that were playing. The music was very vibrant; the whole city was alive with it. I discovered all the pipe music and really got into that. I’d see the titles of tunes written in Gaelic, and I, having grown up with Irish, I’d recognise names; it’s very similar to Irish. And that sparked a deep interest in Gaelic, so I ended up studying a bit of Scots Gaelic in Inverness. It was great to find that connection over here. It really made me feel at home in Scotland in a very connected way with the culture here.

Music at Home—The Blind Fiddler. (Courtesy of the Mary Evans Picture Library)

Most of all, however, family gatherings by the hearth with friends and neighbors were the primary social outlet, especially during the long winter nights. In an era lacking electric power or easy transport, ceilis or ceilidhs were inclusive, regardless of social status and ethnic background. In these circumstances, it is easy to imagine a free flow of oral song and story traditions as described by Len Graham in his biography of legendary Irish musician Joe Holmes:

This sort of ceilidh with song, story, and dance was common to many houses in County Antrim and other parts of Ulster irrespective of religious affiliation and background. The sub-culture of the ceili-house which was the scene of fireside philosophers, rustic bards, storytellers, balladeers, traditional musicians and dancers was that of ordinary people with extraordinary skills and imaginations. The Holmes hearth and homestead was a welcome oasis bringing together neighbors, tailors, tinkers, itinerant musicians and singers which was the “university” of Joe’s learning and experience.14

Stemming from an old Gaelic root word meaning “companion,” the spellings have diverged into the Scottish “ceilidh” and the Irish “ceili”; however, the essence of the tradition is the same. A later definition was “a visit,” and the ceilidh culture retains its drop-in, social spirit. Other tags may capture the idea just as well: “spree,” “song swap,” “kitchen time,” “kitchen racket,” “bottle night,” and “big night.” In the rural areas of Scotland and Ireland prior to modern transportation and entertainment, it was the major social activity throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A warm welcome was guaranteed to all, especially those known to bring stories, songs, instrumental tunes, and dances.

In days gone by, the get-togethers were a forum for sharing the news or gossip of the day. This is not such a central part of the gatherings today, but what has endured is the egalitarian spirit, allowing a social mix of revelers from different backgrounds and places. Poteen (illegal whiskey) was common—and one reason for the clergy to stay away (though this is not necessarily the case any more). Whether the beverage was legal or not, glasses were filled and refilled from the flask, explaining the origin of the name “bottle night.” Within the modest family cottage, the activity centered around the hearth or in the kitchen, which in many cases was the same room. In larger dwellings, one room might host the songs and stories, impromptu and in seamless transition, while dancing was held in another room and sometimes in a barn or outbuilding. This dancing custom gave name to the varieties of ceili and ceilidh dances that

are still extremely popular at parties, weddings, and concerts. At the end of the evening, a parting glass was shared, along with songs for the road from the vast pool of parting songs in the Scottish and Irish repertoire. In some ways, the evening shared elements with the American Wakes; however, there was jollity in the air because the partings were not permanent.

Of all the money that e’er I had, I spent it in good company.

And of all the harm that e’er I’ve done, alas it was to none but me.

And all I’ve done for want of wit, to memory now I can’t recall.

So fill to me the parting glass. Goodnight and joy be with you all.

—“The Parting Glass” (CD TRACK 20)

While the home remained a place for a ceili or ceilidh, over time the ceilidh house—”taigh ceilidh”—became a more common site for gatherings, along with public houses and hotels in recent decades. It is a tradition very much alive and well, with music sessions hosted in many a home, hall, or pub in Ireland and Scotland. The spirit of music making and revelry has followed the Scottish and Irish diaspora to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States. The southern Appalachians would carry on the tradition, in essence if not in name, through jam sessions and song circles from the front porch to the crossroads store.

Music author Aidan O’Hara refers to this coming together of various musicians and their music as a “shared fusing,” unconcerned by the background of the participant—Catholic or Protestant, Irish or Scot, farmer or tradesman.15 As such, the “playlists” for a ceili, usually spontaneous, might include a lively fiddle tune that set the visitors dancing, or a song—sad or humorous—from any origin or era. Nonsense choruses were always enthusiastically shared.

Here I am amongst you and I’m here because I’m here,

And I’m only twelve months older, than I was this time last year, righ-ah,

With me to-righ-ah, with me to-righ-oor-i-ah,

Righ de dom with me to-righ-ah, with me to-righ-oor-i-ah.

Oh, the more a man has, the more a man wants, the same I don’t think true,

For I never met a man with one black eye, that wished that he had two, righ-ah.

With me to-righ-ah, with me tour I oor I ah, etc.16

A well-traveled song that originated in Scotland, was sung at ceilis in Ulster, and eventually found its way to the Appalachians was the “Dark-Eyed Gypsy.” Its many variants go by as many names, all of which reflect the constant enduring themes of love and class. Tracing roots to Scotland as “The Earl o’ Cassillis Lady” or “The Gypsy Laddie” it sailed onward to Ulster to be reborn as “The Raggle Taggle Gypsy.” In the United States, Woody Guthrie learned the song from his mother as “Gypsy Davy.” The popular Appalachian version is “Black Jack Davy.” This is the oral tradition at its busiest—lyrics and titles are changed with careless abandon, but the essence of the story remains constant: the lady of the castle always runs off with the “dark-eyed gypsy o.”

The Scottish version sets the ballad among the characters and countryside of Ayrshire in the southwest:

The gypsies they came to my Lord Cassillis’ yett,

And O but they sang bonny;

They sang sae sweet and sae complete

That down came our fair Ladie.

She came tripping down the stairs

And all her maids before her,

As soon as they saw her weel-far’d face,

They coost their glamourie o’er her.

She gave to them the good wheat bread,

And they gave her the ginger,

But she gave them a far better thing,

The gold ring off her finger.

Will ye go with me, my hinny and my heart,

Will ye go with me, my dearie?

And I shall swear by the staff of my spear

That your Lord shall ne’er come near thee.

Gae tak’ from me my silk manteel,

And bring to me a plaidie;

For I will travel the world o’er

Along with the Gypsie Laddie. (CD TRACK 7)

In “coosting their glamour” or casting a spell over her, the Scots ballad retains a magic and mystery that is missing from the American “Gypsy Davy,” which cuts, literally, to the chase:

It was late last night when the squire came home and he’s asking for his lady

Only answer that he got, “she’s gone with the Gypsy Davy”

[Refrain] Rattle to my Gypsum, Gypsum, Rattle to my Gypsum Davy-O

“Go saddle me up my milk white steed, the black one he ain’t so speedy

I’ll ride all night I’ll ride all day til I bring home my lady”

Well he rode all night until broad daylight til he comes to a river raging,

There he spied his darling bride in the arms of Blackjack Davy

“Come home my true love, come home my honey

I’ll put you in a tower so high where the gypsies can’t come around you”

“Well I won’t come home my true love, I won’t come home my honey

I wouldn’t give a kiss from the gypsy’s lips for all your lands and money”

“Would you forsake your house and home would you forsake your baby?

Would you forsake your husband dear for the love of Gypsy Davy?”

“Yes, I’ll forsake my house and home, I’ll forsake my baby

And I’ll forsake my husband dear, for the love of Gypsy Davy” (CD TRACK 8)

Songs like this, heard throughout the British Isles, Ireland, and the United States, are the footprints of a traditional culture on the move. In their earliest homes, they were usually sung unaccompanied (a ca-pella) and solo in the revered “sean-nós” (“old-style”) tradition. The most riveting sean-nós singers rarely made eye contact, standing quite still and letting the song take center stage. Shared in this way, songs belonged to an entire community, enduring across time and place. Although some came to be associated with great singers in different eras, they belonged to a living communal song pool.17 Over time, people embraced other forms of singing, including two or more a capella singers joined in unison (without harmony)—a particular Ulster style—as well as voices accompanied by different musical instruments.

An Ulster tradition and song style evolved. It resonated with an unmistakable Scottish influence through songs with roots in Aberdeenshire and the Borders of Scotland, in the Highlands and Islands, and in towns. Although Robert Burns never made it to Ulster in his travels, his songs certainly did become popular there. “A Man’s a’ Man for a’ That” Burns’s stirring anthem for equality and justice, was first published anonymously in The Glasgow Magazine in August 1795 and then two months later in Belfast’s Northern Star, a radical newspaper of the United Irishmen. Considered somewhat provocative at the time, it appeared the next year in the London Oracle with authorship attributed to Burns. This caused him concern, as the sedition laws were in force and he was working for the government at the time. His “Address to the Toothache” was first printed in the Belfast Newsletter in September 1797.18 Burns’s larger body of work crossed the North Channel as well, including “Song Composed in August” (“Westlin’ Winds”), “Afton Water” “Highland Mary” “The Banks o’ Doon,” “A Red, Red Rose,” and “Ae Fond Kiss.” All were popular in the different communities of Ulster, his love songs easily covering ground throughout Ireland. The Burns family even fit the profile of Ulster Scots, some migrating from Ayrshire in the southwest of Scotland across the sea. His sister Agnes is buried in St. Nicholas Churchyard, Dundalk, County Louth, and granddaughter Eliza Everitt lived in Belfast’s York Street area. Her daughter entrusted Eliza’s private Robert Burns collection to the Linen Hall Library in Belfast. Another substantial Burns collection belonged to Andrew Gibson, who, like Burns, was a native of Ayrshire. He became governor of the Linen Hall Library, to which he bestowed his internationally significant collection of Burnsiana.

Religious psalms and hymns formed the basis of another song legacy that made the journey from Scotland to Ulster and then to America. When entire Presbyterian congregations followed their ministers on the promise of greater religious and economic freedom, their religious music made the crossing with them. “Singing schools” were common among the Presbyterian congregations in Ulster. These gatherings convened at the meeting house, or at members’ homes, to sing psalms paired with one of the twelve melodies, the “auld twelve” used by the Covenanters of old.19 Group singing was eased along by the old Scottish custom of “lining out” the lyrics, whereby the minister or song leader would “give out the line” one at a time. This practice later proved popular in the southern Appalachians, where hymnbooks were often scarce and illiteracy common. Today, leading by vocal lining out is still used in the Gaelic psalm singing on Lewis in Outer Hebrides and in a few rural churches in the American South, including some African American congregations. Over time, the Ulster Presbyterians introduced hymns and instrumental accompaniment to their services, but not without some resistance.

Len Graham, Irish traditional singer and song collector; interviewed in Swannanoa, North Carolina, July 2013, by Fiona Ritchie and Doug Orr during Traditional Song Week at the Swannanoa Gathering folk arts workshops.

Robert Burns, the national poet of Scotland, is very much loved and admired and recited [in Ulster]. My earliest recollection is hearing songs of his being sung, and versions actually of melodies and interpretations that are very different to what you would find in Scotland, so he was very much revered and still is revered in Ulster. His older sister Agnes married a man [William] Galt from Stephenstown, and she’s actually buried in St. Nicholas’s churchyard in Dundalk in County Louth. His granddaughter, Elizabeth, married a local doctor, Everett, and she lived in Belfast for quite a while. And he had also a nephew, Valentine Rainey, who taught harp in the harp academy in Belfast in the early years of the nineteenth century. See, what you have to remember: there was only one university in Ireland, an Anglican university in Dublin, up until 1840’s, when Queen Victoria built the colleges, the Queen’s colleges they were known [Queen’s University]. Prior to that, the Northern Irish Presbyterians sent their people for third-level education to Scotland. So they were all going over to Edinburgh and St. Andrews, Aberdeen and Glasgow, and coming back and forth, to the extent that Burns, [though] he never came over to Ireland personally, his poetry came over and appeared in the Kilmarnock edition here before the Belfast edition was printed. The ports would be Portpatrick in Galloway and Donegal Bay: those two ports would be in-flowing with people bringing their songs, traditions, poetry, all those cultures were coming back and forth constantly, right, for a long time.

Tunes were played at rites of passage—weddings, christenings, and wakes. Dances would be held at fairs and ceilis, where a fiddler would be called upon to bring the dancers to the floor. By the seventeenth century, the sound was enriched by an array of instruments entering Ireland from other lands, including wooden flutes, tin whistles, accordions, and concertinas. With the arrival of the Boehm system keyed metal flute in the early half of the nineteenth century, classical musicians began to discard their old wooden flutes. Irish musicians also acquired the metal flutes and found them ideally suited to Irish traditional music. When Englishman Charles Wheatstone invented the concertina in 1829, these, along with the melodeons and accordions from continental Europe, soon brought the sound of free reed instruments into the music and had enough volume to hold the floor in dance halls. Percussion drove the tempo; simple tambourines, homemade frame drums constructed with willow branches and leather, and bones or spoons all were used. The jaw harp was common in Scotland, Ireland, and England dating back to the early seventeenth century. This modest instrument had many names across Asia and Europe and was known as the “trump” in Scotland and northern England. It could easily be used in combination with vocal “lilting” of mouth music to provide rhythm for dancing in the absence of pipes or fiddle. The jaw harp (often called the “Jew’s harp”) became a popular companion of the Scots-Irish settlers on the trail southward along the Great Wagon Road into the southern Appalachians.

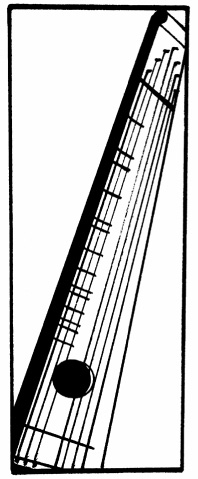

Bagpipes. (Darcy Orr)

Harp from Illustrated British Ballads (1881). (Collection of Darcy and Doug Orr)

The long historical sagas of Ireland and Scotland, if set to music, would surely be played on the small harp and bagpipe. A ninth-century woodcarving in Ireland depicts a piper, and mouth-blown bagpipes were established in Ireland and Scotland from ancient times; there are many tales of bagpipes and music being passed down by minstrels and their oral traditions. In 1396 bagpipes, or “warpipes,” were carried into the Battle of the North Inch at Perth, and there has been a long tradition of Highland pipes being played at battles up into the twentieth century, when the 51st Highland Division used them at El Alamein during World War II. On the Highland bagpipes, “piobaireachd,” or “ceol mor” (big music), the so-called classical music of the “piob mor” (big pipes), dates back to the 1500s, when it was conceived by the MacCrimmon family, hereditary pipers to the Clan MacLeod on the Isle of Skye. However, most instrumental pipe music—reels, jigs, hornpipes, and strathspeys—is dance music dating back little more than three centuries.

It is often claimed that the bagpipes were banned in Scotland under the Act of Proscription, created to weaken the clan system after the defeat of Jacobite Highland clans at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. While wearing tartan and kilts was formally outlawed under the “Dress Act,” no records exist documenting prosecutions for owning or playing pipes. Certainly, the fact that clan chiefs were stripped of their powers would have ended the system of patronage that had supported generations of pipers and harpers. The decline of Highland society and widespread emigration were more contributory to the instrument’s decline. Regiments were raised in the Highlands in the late eighteenth century, and eventually Highland bagpipes were integrated into nineteenth-century regimental life, initially as a rallying instrument to bolster the ranks. The bagpipes have been associated with military bands and Scottish and Irish regiments ever since. In the eighteenth century, bellows-blown bagpipes entered England, Scotland, and Ireland via Europe. Various types of bellows pipes thrive today in Northumberland in England (Northumbrian pipes) and as “cauld-wind pipes” in Lowland Scotland. The most sophisticated of these instruments evolved in Ireland as the “union pipes”; in the twentieth century, these became known as the “uilleann” (meaning “elbow”) pipes.

The primitive harp, still found in Africa, was once widespread throughout the world. Did the harp find its way into the hands of the Atlantic Celts from the ancient European continent? It may be the case that harp instruments were independently born among the ancient people of the British Isles and Ireland, evolving there independently. Certainly, in Ireland and Scotland, the harp has been established since ancient times, as several different stringed instruments were being played in both countries by the eighth and ninth centuries. Images of triangular-framed harps were carved onto Pictish stones on the east coast of Scotland in the eighth century.1 Irish carvings show lyres from this era, and the first triangular framed harp appears on a carved stone in Ireland in the twelfth century. So we know that harp-like instruments have been played in Scotland and Ireland for more than 1,200 years. The earliest ancient specimen, the Brian Boru harp, dates from the thirteenth century and is housed in Trinity College, Dublin.

The small harp, or “clarsach” (Scotland) and “clairseach” (Ireland), played an important role in the ancient culture and identity of both countries. This was the instrument of the aristocracy, who held their professional harpers in high regard. Traditionally, harpers would accompany epic poetry of great heroic and tragic tales. Their patrons expected them to be able to summon tears, laughter, and sleep. They played laments, lullabies, and formal listening music that, in Scotland, may have provided inspiration for the highly stylized theme and variations “ceol mor” (“big music”) or “piobaireachd” of the bagpipe repertoire. Harpers were performing the art music of their day, and, like many song tradition bearers, they considered it a point of pride that their music was not written down. They carried their tunes, poetry, and tales in memory, passing them orally from teacher to pupil and from player to player. It may be that much of the older music composed for the harp was picked up on bagpipe and fiddle as the harp waned in popularity with the fading of the traditional clan-based society, often termed the “old Gaelic order.”

The 1790s saw the beginnings of modern Irish nationalism, accompanied by a cultural revival that injected momentum into efforts to document traditions in music and language. This awareness of an endangered cultural heritage coincided with a sharp decline in harp playing. In response, Belfast citizen Dr. James MacDonnell organized a gathering of harpers in the city, intending to witness and record the ancient music of the Irish harpers before it disappeared. He engaged the services of organist Edward Bunting to transcribe their music. Ten harpers, six of whom were blind, attended the festival and played their tunes over a three-day period, including ninety-seven-year-old Donnchadh Ó hAmhsaigh (Denis Hempson, 1696–1807). The melodies set down by Bunting for his General Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland (1796)—the riches of an era of orally transmitted music reaching back centuries—were captured just in time. Bunting then traveled throughout Ulster to complete his first volume of tunes and followed with two more in 1809 and 1840, including dances and pipe airs, some of which would have been adopted as song melodies. The music contained in Bunting’s collections offers a glimpse of a passing age in rural Ireland, when music, like song, existed only as an oral tradition.

1. Keith Sanger and Alison Kinnaird, Tree of Strings (Temple, Midlothian, Scotland: Kinmor Music, 1992), 20.

Sorrowing harp from Illustrated British Ballads (1881). (Collection of Darcy and Doug Orr)

The small harp has been made and played in Scotland and Ireland since at least the eighth century, when its image was hewn onto Pictish stones from that era in Scotland’s North East. Both countries supported a system, over a period of centuries, where clan chiefs and other gentry patronized hereditary resident pipers and other itinerant musicians. Many of these were harpers who would visit their patrons’ homes in an extended grand tour. Much traditional Highland music was composed under this system of patronage by legendary harpers, such as Rory Dall Morison (“blind Rory” 1656–1713). After English colonization began in Ireland under Henry VIII, harpers, pipers, and other wandering musicians were often routed out. By 1640, Oliver Cromwell’s troops would ruthlessly track and kill pipers and destroy their instruments, as the army of Elizabeth I had done sixty years earlier. Although no longer outlawed, the status of harpers was very much diminished by the end of the seventeenth century. The blind harper Turlough O’Carolan (1670–1738) was born during a relatively peaceful time when the ancient harp was staging a brief comeback among the landed gentry. Smallpox had robbed him of his sight, so he studied harp to make his living playing in the big houses of the few remaining wealthy landowners. He would be expected to recite, sing, and compose for his patrons, the remnants of a ruling class for whom the harp was a beloved bond to a more-glorious past. Car-olan composed more than 200 melodies and became known as the “last of the Irish Bards.” Many compositions, some of which he called “planxtys,” were named for his patrons and are still popularly played today.

In Ulster, however, the voice of one instrument rose above all others at dances and music sessions. The fiddle had migrated to the western reaches of Europe from the Continent, and so did some of its dance-tune repertoire. In his book Folk Music and Dances of Ireland, Brendan Breathnach maintains that the reel, schottische, and strathspey come from Scotland; hornpipes come from England; most of Europe had some variation of the jig; and polkas and mazurkas have origins in eastern Europe.20 It was all stirred into the cultural broth of the Ulster Scots and Irish, seasoned and served up as their own.

In Ulster halls and homes, fiddlers gave their tunes a Scottish or Irish definition. Many are familiar today in the Appalachians: “Blackberry Blossom,” “Miss McLeod’s Reel” “Soldier’s Joy” and “Flowers of Edinburgh” In fiddle music, an atavistic return to roots running deeper than memory gave voice to the old Celtic reverence for beauty, passion, and romance, as Len Graham captured in “The Fiddler”:

The fiddler with ancient art,

Fingering and bowing, heard and unheard melody,

The sensitive lug, the inherent part,

No man can drum into you.

Rhythm and time; notes with “ghost,”

Pass over inept ears.

But to those who know—no mighty host,

A few unsung peers.21

Sara Grey, American traditional singer, banjo player, and song collector; interviewed in Perth, Scotland, March 2010, by Fiona Ritchie at the singer’s home.

I’ve heard a lot of songs from the North of Ireland . . . because my husband’s family to-ed and fro-ed a lot between that part of Dumfries and Galloway and Northern Ireland, where the crossing is short. But when it comes to songs, when you listen to the style in Northern Irish singing, it’s quite different from the Scots style of singing. Every area: the big ballad areas of the North East of Scotland, the midland area—the Lowlands Scots, the Border Scots, and the Western Isles, they don’t sound like Northern Irish singers. There’s a cadence that the Northern Irish singers have that’s quite different from the sean-nós style of singing certainly, and I think it’s very different than the lyrical Border ballads style that you get and the lyrical style that you get in the North East of the big ballads.

And somewhere along the line, I don’t know if you’ve found this, but Ireland got bypassed when it came to a lot of the big ballads. You know, I don’t think England gets enough credit for the ballads because the big ballads were primarily Scotland and England. Some of them dropped from Ireland, but most of them went from England and Scotland and then to Ireland and then across the pond. And sometimes they bypassed Ireland all together, and I’ve sung with so many different Irish people who know very few of the big ballads, you know. And it’s something that’s puzzled me, I’ve never known quite why that is so. I mean, when you listen to the Ulster people sing, it’s just almost like a spoken word, it’s almost like the Ozark region. ‘Cause I’ve done a lot of listening to old singers around Mountain View and Timbo, Arkansas, and you get that almost extended lines where they’re wonderful, they’ re a little bit—what’s the word they use for it? Oh, “crooked”: you get slightly crooked songs.

People, goods, and languages were all intermingled in the historic comings and goings between Scotland and Ulster, especially its three most northerly centers of Antrim, Derry-Londonderry, and Donegal. The rocky reaches of the Atlantic shores became home to an extended musical society that would eventually make its way to America. Fair Head on the Antrim coast is the closest point to Scotland, with the Mull of Kintyre in Argyll only twelve miles away. The ancient kingdom of Dalriada encompassed a large swathe of present-day County Antrim and Scotland’s Argyll and Bute, including the Scottish Western Isles. The kingdom’s independence ended by the end of the eighth century with the arrival of the Vikings, who marked the area with a Norse imprint. However, Donegal’s deeply rooted ties with Scotland extend back more than 1,500 years. It is often said that the people of Donegal historically looked toward Scotland and Spain more than Dublin and London for their commerce and culture. Donegal is one of nine counties within the ancient boundaries of Ulster, although today it is one of three, along with Cavan and Monaghan, that are now part of the Republic of Ireland. A simple scan of the map, forgetting present-day borders, makes sense of the Scottish-Donegal connection. Inishowen Peninsula protrudes into the North Channel in clear sight of Kintyre and the Scottish Hebridean islands of Jura and Islay. Early people managed to navigate that twenty-mile-plus crossing in the first post-Ice Age migrations from Britain to Ireland. Centuries later, seasonal migrations of Irish farm laborers traveled in the opposite direction, following many routes to Scottish farms. Today it is all very routine, with a daily ferry/bus service between Inishowen and Glasgow. Locals joke that “Scotland is the northernmost county of Ulster.”22

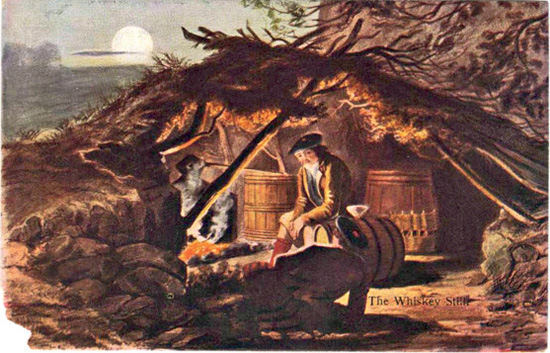

UISGE BEATHA: THE WATER OF LIFE

The ethnonationalistic conflict, known colloquially in Northern Ireland as “The Troubles,” is a tragic demonstration of the consequences of imposed change. There are many other legacies of the Ulster Plantation era of King James VI and I, some more benign than others. One of the more permanent—and welcomed—legacies was the license to distill granted by King James to Sir Thomas Phillips, landowner and governor of County Antrim. This allowed him to found the Bushmill’s Distillery near the Giant’s Causeway in 1608, almost within sight of his sovereign’s motherland. Not only the first distillery in the British Isles, Bushmill’s is now the oldest licensed whiskey distillery in the world. Subtle and distinct differences mark the shared heritage of this legendary beverage. First, it is spelled slightly differently: “uisge beath” or “whisky” in Scotland and “uisce beatha” or “whiskey” in Ireland, both meaning “lively water” or “the water of life.” Irish whiskey must be distilled three times and stored in casks for a minimum of five years before it can officially be labeled as whiskey. For Scotch whisky, the requirement is twice distilled and then aged for a minimum of three years. The triple-distillation Irish whiskey can be the smoother beverage and has considerable potency. While the Irish usually blend their whiskey, however, the Scots maintain their distinguishing tradition of distilling Single Malts as well as blends. Both are made from fermented grain mash and from different grains—barley, malted barley, wheat, rye, and corn—and are typically aged in oak casks. Bourbon, sherry, and port barrels are recycled from other drink manufacturers, and this gives the different labels their special taste characteristics.

Distillation is an ancient art, possibly tracing back to the Babylonians in Mesopotamia and subsequently to the Greeks in the third century A.D. Thirteenth-century Italian monasteries were the first places to record the distillation of alcohol from wine. The practice came to Scotland and Ireland in the early fifteenth century, and King James IV of Scotland, in addition to his taste for music, had a liking for the early Scotch whiskies. From the fifteenth century, whisky was heavily taxed in Scotland, and most of the spirit was illegally produced. The English Malt Tax of 1725 essentially drove Scotland’s whisky manufacturers underground, launching a tradition of illegal distilling that eventually spread to America and the Appalachian Mountains. Scottish distillers came up with creative subterfuges, operating homemade stills out of sight of the government excise men (the infamous “revenuers” in America) and under the cover of darkness—hence the name “moonshine.” In 1823 Parliament finally passed an act that penalized unlicensed distilling and made commercial distilleries profitable in Scotland.

From the very beginning, the colorful stories of making and imbibing the “sacred juice” were tailor-made for poets and song makers; “Whiskey You’re the Devil,” “Nancy Whisky,” “Fare Ye Weel Whisky,” “The Moonshiner,” “Gie the Fiddler a Dram,” “Whiskey in the Jar,” and “A Bottle o’ the Best” are but a few examples. Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson hinted at the illicit nature of the refreshment shared by three friends “while the mune was shinin’ clearly,” while Robert Burns made it clear that the bravado of his everyman hero Tam o’ Shanter was very much bottle sourced: “Wi’ tippenny, we fear naeevil; Wi’ usquebae we’ll face the devil!” Len Graham collected “Flowing Bowl,” an old Glens of Antrim song in praise of Irish whiskey:

Oh the whiskey me boys keeps my mind alert and free,

’Tis the whiskey that makes life’s cares lie light on me,

Each bold rustic bard it is hard that he should be denied,

Of his darlin’ reward that his pipes well with oil be supplied.

It cures all diseases that seizes the human frame,

The heart-ache it eases, the toothache, the gout and the spleen,

The coughing, stuffing, water-stopping, the stone and the small-pox,

By it buying and supplying you would close up Pandora’s box.

Glens of Antrim (Oil painting; courtesy of Hugh O’Neill, b. Belfast, County Antrim, Northern Ireland, 1959)

Whisky Still in the Moonlight; Mclan postcard. (Courtesy of Photo Archives, Inverness Museum and Art Gallery, High Life Highland, Scotland)

Whisky barrels at a distillery. (Watercolor; courtesy of Madeleine Hand)

Evening at Edradour (whisky distillery). (Watercolor; courtesy of Madeleine Hand)

Inishowen had a notorious reputation for distilling illicit “poitín” (poteen, or Irish moonhsine), and Scottish influences are significant on the legal distillery business. Intermarriage was more commonplace here than elsewhere in Ulster, and tunes were traded as commonly as drams of whiskey. The short staccato bow strokes of the Donegal fiddle style set it apart from the rest of Ireland. This freer and less-ornamented style would one day crop up in the southern Appalachians. Donegal voices amalgamated phrasing from Irish sean-nós singing with Hebridean pitch and tempo and Scots wording. Eventually, the “high lonesome sound” of the Appalachian and American bluegrass styles harked back to the sound of early Donegal voices.

SENSE OF PLACE

This is my country,

The land that begat me.

These windy spaces

Are surely my own.

And those who toil here

In the sweat of their faces

Are flesh of my flesh,

And bone of my bone.

—Sir Alexander Gray, “Scotland”23

Many cultures celebrate the idea of home in their music, stories, and literature but few people have their sense of place etched as plainly on their hearts as the Scots and Irish. Irish scholar Linde Lunney described the feeling of belonging to Ulster.

It has been said that if you know where you are you know who you are . . . and in the north of Ireland you still occasionally hear someone say something like “Johnny Archibald belonged to Ballymoney” or “Sammy Taggert belonged to Bal-lyportery.” The concept that an individual in some sense is owned, presumably in perpetuity, by the place where he is born is a wonderfully strong and poetic way of describing the merging of self and background. Even if you willfully tear up your roots, you still belong to that place, and cannot not belong there.24

It is an eternal feeling, this longing for home and nostalgia for the old familiar place. As ever, poets and song makers are best placed to capture the sentiments. The word “nostalgia” stems from the Greek word for a return home. Home is an eternal compass, guiding life’s journey, an abiding memory or a real destination for the return trip. A village, hillside, stream, road, or waterside, named for a setting in a far-off land, will trigger deep emotions. For Irish Nobel Laureate Seamus

Heaney, the poet’s sense of place ideally rose above physical landscape and “picturesqueness,” becoming “a country of the mind.”

Tory Island, Knocknarea, Slieve Patrick, all of them deeply steeped in associations from an older culture, will not stir us beyond a visual pleasure unless that culture means something to us, unless features of the landscape are a mode of communication with something other than ourselves, something to which we ourselves still feel we might belong. . . . As we pass along the coast from Tory to Knocknarea, we go through the village of Drumcliff and under Ben Bulben, we skirt Lissadell and Innisfree. All of these places now live in the imagination, all of them stir us to responses other than the merely visual, all of them are instinct with the spirit of the poet and his poetry . . . our imaginations assent to the stimulus of the names, our sense of the place is enhanced, our sense of ourselves as inhabitants not just of a geographical country but a country of the mind.

—Seamus Heaney, “The Sense of Place,” Preoccupations25

This depth of connection to the “country of the mind” surely explains why the Irish and Scots have managed to engrave their place names on features of the physical landscape in every continent. It follows that the towns and landscapes of Scotland and Ireland are among the most heavily cited of any of the world’s song traditions. In Scotland, “The Gallowa’ Hills,” “The Road to Dundee,” “The Loch Tay Boat Song,” “Bonnie Glenshee,” and “The Dowie Dens of Yarrow” barely scratch the surface of the inventory. From Robert Burns, “The Birks of Aberfeldy,” “The Banks o’ Doon,” and “Sweet Afton” are but three compositions that demonstrate the bard’s unfettered urge to publicize his fond feelings for the landscapes of home. On the Ulster side, “Star of the County Down,” “Slieve Galleon Braes,” “Carrickfergus,” “The Banks of Claudy,” “Boys from the County Armagh,” and “Fare Thee Well to Enniskillen” are, again, just a few from a long list of titles. The Republic of Ireland would show a good many more. Beyond the titles, lyrics of traditional songs are a directory of town and country from Belfast to Glasgow, between and beyond.

I wish I was in Belfast town and my true love along with me,

I would get sweethearts plenty, to keep me in good company,

With money in my pocket and a flowing bowl on every side,

Hard fortune ne’r would daunt me, while I’d be young in this world wide.

—“The Rambling Boys of Pleasure”

My name is Jamie Raeburn, frae Glasgow toon I came;

My place and habitation I’m forced to tae leave wi’ shame;

From my place and habitation I now maun gang awa’,

Far frae the bonnie hills and dales o’ Caledonia.

—”Jamie Raeburn”

As Ulster Scots made ready to sail onward again, they sang from the heart in their native dialect of homelands past and present. Their artistic descriptions were cultural archives and personal directions, all memories to treasure and transport.

TO CANAAN’S LAND

The Promise of America

To Canaan’s land I’m on my way where the soul of man never dies,

And all my nights will turn to day where the soul of man never dies.

—“To Canaan’s Land” (American spiritual)

But Moses being a holy man got orders from God,

And from the house of bondage set his children free.

And led them to fair Canaan’s land,

Where they have cause to weep no more,

Yet after all he brought them to the land of liberty.

And perhaps we’ll meet again in time where milk and honey flows.

—“Campbell’s Farewell to Ireland”

The biblical land of Canaan has been held as a timeless symbol of the Promised Land for history’s emigrants and refugees. The lyrics of the spiritual join together the hopes of enslaved Israelites in Egypt with the destitute and the desperate seeking passage to America’s land of liberty, as well as the “Hereafter” destination of American hymn singing. “Canaan” also was a code word for the slaves of the American South pursuing the Underground Railroad route to the North and Canada. “Campbell’s Farewell” likely traces its roots to the eighteenth-century Presbyterian emigration from Ulster, the Campbells being a prominent and staunchly Protestant clan in the west of Scotland. Like the spirituals of the South, it makes the universal plea: a cry for a better chance over the horizon.

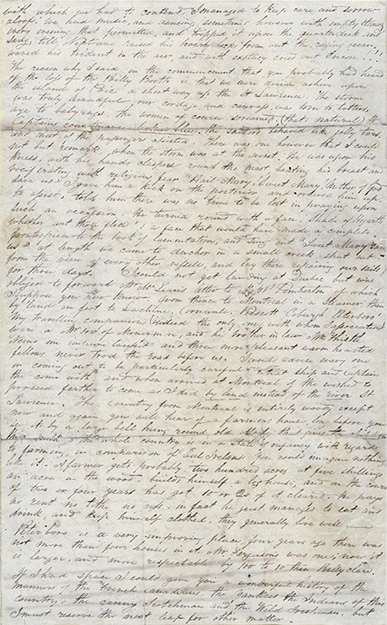

Whether from countryside to city or across national boundaries and oceans, factors that drive people onward are universal. “Push” forces come into play as life becomes unbearable owing to political, economic, or cultural challenges. The “pull” of another place offering greater opportunity and the promise of freedom from oppression, including religious persecution, completes the cycle. The Ulster Scots began to feel the pull of Canaan’s land of milk and honey, which they imagined flowing across the American soil, as they became disillusioned in their still relatively new homeland. The Scottish settlers that had left their ancestral homes and crossed the sea to Ulster held high expectations for their new lives and prosperity. Initially, their lives were improved. The eighteenthcentury Plantation system in Ulster was governed and controlled by a small landowning elite. In London, the Guilds that were expected to fund the plantation project diverted their attention to New World plantations around Jamestown, Virginia, and many British Protestant settlers emigrated there or to New England. More than that, it was mounting economic and religious discrimination that combined to alienate the discouraged Ulster Scots. Parliament in London decreed that Anglican Protestantism, the Church of England, be the official denomination for the Ulster Scots. They established severe penalties for dissenters who refused to fall in line, a practice already firmly in place for the native Irish Catholics. Having been pioneers for their new faith, Ulster Presbyterians were now a persecuted people. The Church of Scotland, Presbyterian, was officially recognized in 1690, and so it became commonplace for Ulster Presbyterian ministers to journey to Scotland for sermons. Presbyterians living close to the east coast of Ulster might even cross the North Channel to have their children christened. Jaded Ulster Presbyterian ministers began to fan the vapors of discontent among their parishioners, promoting emigration.

The economy was even more forceful in the push Ulster Scots felt toward America. A rent escalation practice known as “rent racking” and a decrease in the length of land leases made it increasingly difficult for the settlers to sustain a living. The population had grown, and land was scarcer. Paying more for less made no sense. Recurring crop failures and poor prices for meager harvests sealed the argument. They could also see that in Scotland, where Presbyterian Calvinist values were by now embedded, an egalitarian and democratic spirit was spreading. As David Fischer writes in Albion’s Seed, “They were increasingly exploited by rent-racking landlords, bullied by county oligarchies and taxed by a church to which they did not belong.”26 They seemed hopelessly trapped in an oppressive economic and political vice: “Betwixt landlord and rector, the very marrow is squeezed out of our bones.”27 The traditional Ulster ballad “Slieve Gallion Braes” makes the case clear:

My name is James McGarvey, as you may understand,

I come from Derrygennard where I owned a farm of land.

But the rents were getting higher and I could no longer stay,

So farewell unto you bonny, bonny, Slieve Gallion Braes.

It was not the lack of employment alone,

That caused the poor sons of old Erin to roam.

But it was the cruel landlords who drove us all away,

So farewell unto you bonny, bonny Slieve Gallion Braes.