Generosity contest—last to be jettisoned—the expansion mechanism—Joe’s dexterity—midnight—the doctor’s watch—Kennedy’s watch—he dozes off—the blaze—shrieks—out of range.

Right off Dr. Fergusson took some star sights and fixed his position; he was barely twenty-five miles from the Senegal River.

“All we have to do, my friends,” he said after tapping his map, “is to cross the river; but there are no bridges or rowboats, so we must cross by balloon at any cost; therefore we need to lighten her still more.”

“But I’m not too clear on how we’ll manage that,” the hunter replied, worried about his weapons. “Unless one of us agrees to be jettisoned and left to bring up the rear … and it’s my turn to claim that honor.”

“Blimey!” Joe replied, “Haven’t I gotten good at—”

“This isn’t about jumping overboard, my friend, but reaching the African coast on foot; I’m an expert hiker, an expert hunter—”

“I’ll never go along with it!” Joe shot back.

“My gallant friends, you aren’t in a competition to see who’s the most generous,” Fergusson said. “Hopefully such an extreme measure won’t be necessary; but if it is, we won’t separate—we’ll cross this country together.”

“Now you’re talking,” Joe said. “It wouldn’t hurt us to go for a little stroll.”

“But beforehand,” the doctor went on, “we’ll do one last thing to lighten our Victoria.”

“What?” Kennedy asked. “You’ve got my curiosity up.”

“We need to get rid of the tanks for the burner, the Bunsen battery, and the coil; they’re a weight of nearly 900 pounds that we’ve had to carry through the air.”1

“But Samuel, how will you get your gas to expand?”

“I won’t; we’ll manage without it.”

“Hear me out, my friends; I’ve meticulously calculated the lifting power we’ll have left; it’s enough to carry all three of us plus the few items still remaining; we’ll weigh barely 500 pounds including our two anchors, which I want to hold onto.”

“My dear Samuel,” the hunter replied, “you’re better informed on these matters than we are; you’re the only one who can assess the situation; tell us what we should do, and we’ll do it.”

“Just say the word, master.”

“I repeat, my friends—no matter how serious this decision may be, we need to jettison our mechanism.”

“We’ll jettison it!” Kennedy shot back.

“Let’s get going!” Joe urged.

It wasn’t an easy task; they had to dismantle the mechanism piece by piece; first, they took out the mixing tank, then the tank for the burner, and finally the tank in which the water was broken down; it required nothing less than the combined strength of all three travelers to wrench these containers from the bottom of the gondola where they had been tightly fitted in; but Kennedy was so muscular, Joe so crafty, and Samuel so ingenious, they prevailed in the end; the different pieces vanished consecutively over the side and into the sycamores below, making huge gaps in the foliage.

“Those Negroes will be pretty startled,” Joe said, “to bump into things like that in the woods; they could turn ’em into idols!”

Next they had to deal with the pipes running from the coil up inside the balloon. Joe managed to sever their rubber joints a few feet above the gondola; but as for the pipes themselves, they were more trouble because they were secured at the upper end, and brass wires fastened them right to the valve wheel.

That’s when Joe put on a marvelous display of dexterity; in his bare feet so he wouldn’t scratch the envelope, he clung to the netting and managed to climb all the way up the outside of the balloon, despite her shaking and shivering; after a thousand difficulties he got to the very top, hung on by one hand to that slippery surface, and undid the outside bolts that held the pipes in place. The latter were easy to remove, and they drew them out the lower appendix, which they tied off tightly so it was hermetically sealed.

Freed of this considerable weight, the Victoria rose straight into the air and pulled the anchor rope taut.

By midnight they had successfully finished these various tasks and were seriously exhausted; they ate a quick meal of pemmican and cold grog, since the doctor no longer had any heat to put at Joe’s disposal.

In any case the lad and Kennedy were dropping from exhaustion.

“Lie down and get some sleep, my friends,” Fergusson told them. “I’ll take the first watch; at two o’clock I’ll wake Kennedy up; at four Kennedy will wake Joe up; at six we’ll set out, and heaven protect us during this last travel day!”

The doctor’s two companions needed no coaxing, stretched out in the bottom of the gondola, and immediately fell sound asleep.

It was a peaceful night; a few clouds crowded against the moon in her final quarter, her tentative rays barely breaking through the darkness. Leaning an elbow on the gondola’s rim, Fergusson looked all around him; he kept a careful eye on the dark curtain of foliage that spread beneath his feet and hid the ground from his view; the tiniest noise aroused his suspicions, and every time the leaves rustled, he launched a full investigation.

He was in that frame of mind, intensified by solitude, in which nebulous terrors flood the brain. At the end of such a journey, after a fellow has overcome so many obstacles and right when his goal is within reach, his fears are more vivid, his feelings become more intense, his destination seems to recede before his eyes.

What’s more, their current circumstances were anything but comforting—out in a barbaric country, using a means of transportation that, when all was said and done, could fail him at any moment. The doctor no longer relied wholeheartedly on his balloon; gone were the days when he could do daredevil maneuvers because he had confidence in her.

While processing these feelings, the doctor thought he detected muffled noises down in those huge forests; he even thought he saw a flame flare up momentarily between the trees; he looked intently and aimed his night glass in that direction; but nothing was visible, and the silence seemed to grow even deeper.

No doubt Fergusson was having hallucinations; he listened without detecting the tiniest sound; his spell on watch ending at that point, he woke Kennedy up, urged the hunter to be exceptionally vigilant, and took his place next to Joe, who was sleeping with all his might and main.

Kennedy placidly lit his pipe and rubbed his eyes, which he had trouble keeping open; he leaned on an elbow in one corner and puffed energetically to drive his sleepiness away.

The most abject silence reigned around him; a mild breeze stirred in the treetops and gently rocked the gondola, lulling the hunter into a sleep that was coming over him in spite of himself; trying to resist, he blinked his eyelids several times, peered into the night with a couple of those glances that don’t really see anything, then finally yielded to exhaustion and dozed off.

How long was he plunged in that state of inertia? He couldn’t answer this question when he woke up, a development abruptly caused by an unexpected crackling sound.

He rubbed his eyes, got to his feet. Intense heat struck him in the face. The forest was in flames.

“Fire! Fire!” he yelled, not at all clear on what was happening.

His two companions got up again.

“What’s the matter?” Samuel asked.

“It’s a major blaze!” Joe said. “But who could’ve—”

Just then there was an outburst of shrieking beneath the starkly lit foliage.

“Lumme, savages!” Joe exclaimed. “They set the forest on fire to make sure we burn up!”

“Talibas!” the doctor said. “Probably marabouts serving El-Hadj Umar Tall!”

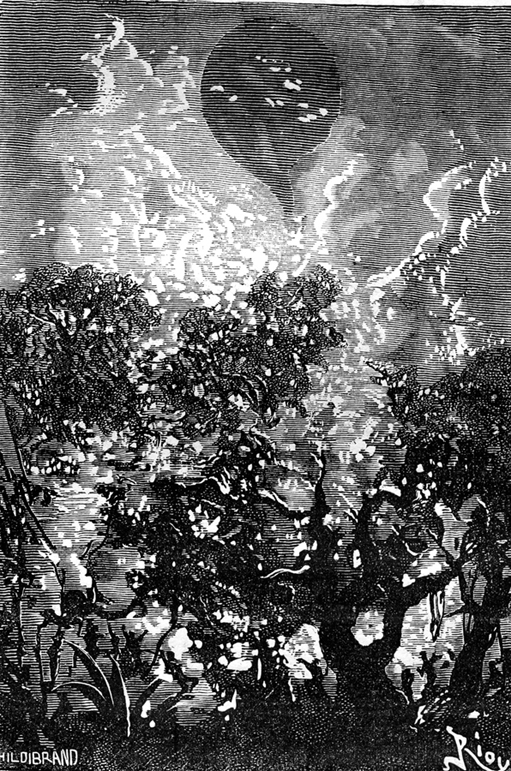

A ring of fire surrounded the Victoria; the crackling of deadwood mingled with the fizzing of green branches; creepers, leaves, and every living piece of vegetation were writhing in that lethal fire; your eyes saw only an ocean of flames; tall trees were outlined in black against the inferno, their branches covered with blazing coals; that cluster of flames, that conflagration, reflected off the clouds, and the travelers felt they were trapped inside a fireball.

“Run for it!” Kennedy yelled. “Climb down! It’s the only chance we have!”

But Fergusson held him back firmly, rushed to the anchor rope, and chopped it through with a single swing of the axe. Stretching up toward the balloon, flames were already licking at her glowing walls; but the Victoria had been released from her bonds, and she climbed over a thousand feet into the skies.

Fearsome shouts rang out in the forest below, then sharp cracks from firearms; caught in an air current that sprang up with the dawn, the balloon headed west.

It was four o’clock in the morning.