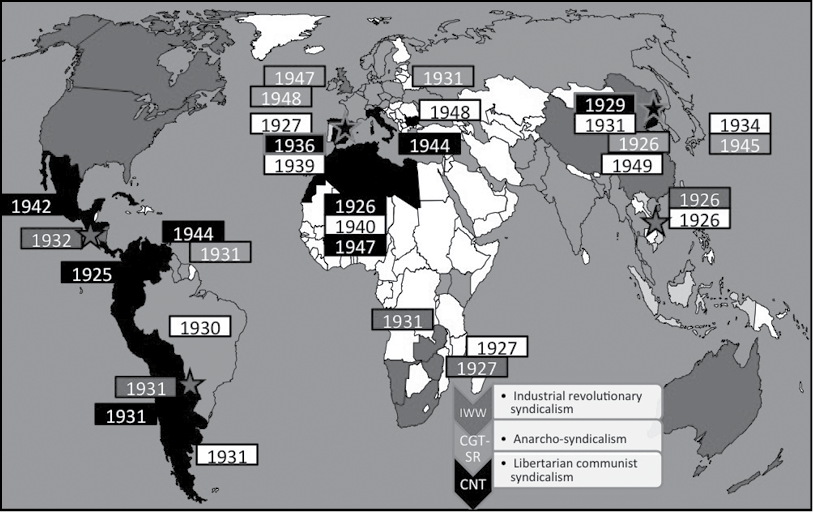

The Third Wave, 1924–1949

The Anarchist Revolutions Against Imperialism, Fascism, and Bolshevism

The Conservative counter-revolution of the 1920s generated anarchism’s greatest challenge, that of two opposing totalitarianisms, Fascism and Bolshevism, which would crush the autonomous, militant working class in a deadly vise for decades to come. Bolshevism was in many ways more insidious than Fascism, establishing a similar style of totalitarianism, but posing as the liberator of the working class under the “dictatorship of the proletariat” (an early Marxist idea coined by former Prussian military officer Joseph Weydemeyer and expanded on by Marx and Engels). In Russia, the dictatorship’s class structure was cynically revealed when Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky explicitly demanded the regimentation of labour. Disoriented by the propagandist success of the Bolshevik model and silenced in its gulags, anarchism lost ground throughout the world. It did retain strongholds in Latin America and the Far East, while in Brazil, China, Egypt, France, Mexico, Portugal, and South Africa, anarchists helped establish the first “communist” parties, which were initially noticeably anarchist and syndicalist in orientation or, at least, deeply influenced by anarchism/syndicalism until they were Bolshevised on Moscow’s orders. It was, however, an era not solely about repression: the Second Wave broke against reformism, the new welfare state sugar-coating that defused militancy in countries as diverse as Uruguay, Sweden, and the USA. While many anarchist/syndicalist organisations were forced underground or destroyed in this long slide into darkness, important struggles against fascism and imperialism were unfolding in countries such as Bulgaria, Korea, and Poland.

In Poland, the anarchist movement had first consolidated during the Russian imperialist period in 1907 with the formation of the Federation of Anarchist-communist Groups of Poland and Lithuania (FAGPL), which operated clandestinely—yet several of its militants were executed by the Russian authorities for belonging to the organisation. A new generation established the Anarchist Federation of Poland (AFP) in 1926 in independent Poland, and before long, a syndicalist General Workers’ Federation (GFP) of about 40,000 members emerged. But in the same year, Poland and Lithuania fell under the dictatorship of the socialist ultra-nationalist Jozef Pilsudski, who in 1930 forcibly merged the GFP with nationalist, independent, and socialist unions to form the Union of Trade Unions (ZZZ) as as a yellow union affiliated to his regime—an odd mix of socialists, liberals, and right-wing ex-soldiers—albeit structured along the lines of the reformist syndicalist French CGT). But the ZZZ grew to 170,000 members and became dominated by the syndicalists who aligned as a tendency to the IWA. When the inevitable clash with their employers and the state came, the conservative unions in the ZZZ such as the munitions workers broke away, leaving the remainder to be radicalised by the anarcho-syndicalists. The ZZZ was forced underground by the Nazi invasion in 1939 but reformed as the clandestine Polish Syndicalist Union (ZSP) with perhaps 4,000 members, and was active in the underground resistance to Nazism, publishing papers, cooperating with the Home Army, and, though its contribution is seldom recognised today, participating directly in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising through bodies like the 104th Syndicalist company.75

It is also worth sketching briefly the trajectories of the two movements who, more than most, would be tested in the fires of fascism: those of the Italians and of the Germans. The Italian movement was born in the nationalist Risorgimento, which united the scattered Italian principalities in 1861, and a section of Bakunin’s Brotherhood was set up three years later. The movement became involved in localised insurrections in 1874 and 1877, which failed, and despite the popularity of the creed, struggled to establish a national organisation: their efforts in establishing the Italian Workers’ Party (POI) in 1882 and the Revolutionary Anarchist Socialist Party (PSAR) in 1891 were wasted as the organisations merged, expelled the anarchists and formed the Italian Socialist Party (PSI); but the syndicalists came to dominate many of the regional Chambers of Labour that were combined in 1906 under Marxist PSI auspices into the General Confederation of Italian Workers (CGIL)—the syndicalists were later expelled, but had managed to form a 200,000–supporter rank-and-file network within the unions. In 1912, this network finally formed an anarcho-syndicalist federation, the Italian Syndicalist Union (USI) with 80,000 members.

Having survived World War I, the syndicalist movement grew dramatically during the Bienno Rosso, the “two red years” of 1919 and 1920 when perhaps 600,000 workers occupied their factories, with the USI growing to a respectable 800,000–member minority (the Marxist CGIL had 2.15 million members by 1919, while the conservative unions collectively mustered 1.25–million members). In 1919, a hardline Union of Communist Anarchists of Italy (UCAI) was founded, but was absorbed the following year into the less ideologically rigorous Italian Anarchist Union (UAI), which peaked at 20,000 members. In 1921, the UAI urged the creation of a “United Revolutionary Front,” bringing together all leftist forces to combat the rising threat of Fascism. But the Marxist PSI had refused to throw the weight of their CGIL unions behind the factory occupations and by the time of the Fascist “March on Rome” in 1922, the left was demoralised and the numbers of organised workers had fallen sharply; by 1927, with Fascism in full swing, veterans of the USI and UAI lived a twilight life in the resistance—but the once-powerful Marxist CGIL meekly dissolved itself when ordered to do so by the Fascists.76

The patchwork of German states had only united in 1871, and for the first three decades, the left suffered under severe anti-socialist laws. So it was only in 1901 that the German syndicalist movement had arisen, when the “localist” tendency within the dominant Marxist Social Democratic Party (SPD) unions split from the SPD and organised as the Free Association of German Trade Unions (FvDG). This soon developed in an anarcho-syndicalist direction under the influence of the French CGT, and of indigenous anarchist and anti-party, anti-state socialism. The membership of the FvDG stood at 18,353 in 1901, compared to the 500,000 members of the Free Trade Unions (FG) linked to the SPD. In 1903, groups across the country formed the German Anarchist Federation (AFD), which worked closely with the FvDG; they were the only left-wing revolutionary organisations in the country on the outbreak of World War I, when the AFD transformed itself into the underground Federation of Communist Anarchists of Germany (FKAD).

The FKAD and FvDG emerged from the war with unsullied reputations for resistance to militarism, and in the heady revolutionary days after the collapse of the German monarchy in 1918, the FvDG expanded to over 100,000 members, and was renamed the Free Workers Union of Germany (FAUD), this time concentrated in the industrial Rhineland and Westphalia and dominated by metalworkers and miners. But the FAUD lost ground on the Rühr to the nascent Bolshevik party—and there were significant revolutionary syndicalist movements to contend with too: even though the FAUD rose to 200,000 members by 1922, it never managed to merge with the 300,000 members of the IWW-styled General Workers’ Union of Germany (AAUD), nor with the MTWIU’s 10,000 members on the docks, nor even with the more radical anti-Bolshevik syndicalist splinter of the AAUD, the General Labour Union—Unity Organisation (AAU-E) which reached 75,000 members by 1922. This endemic fragmentation of the German left was to prove fatal when the Nazis rose to power in 1933—by which time the FAUD was a shadow of its former self.77

Yet it was also amidst this turmoil that, in 1928 and 1929, two huge continental anarchist organisations were founded. Firstly, the East Asian Anarchist Federation (EAAF), with member organisations in China, Japan, Korea, Formosa (Taiwan), Vietnam, and India, was initiated by the Korean Anarchist Federation’s Chinese exile section (KAF-C), which also established the Korean Youth Federation in South China (KYFSC) in Shanghai in 1930, with delegates from Korea, Manchuria, Japan, and all over China.78 Secondly, the American Continental Workingmen’s Association (ACAT) was born, a Latin American IWA formation with member organisations in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay, which held a founding congress that drew about 100 unions from across the continent.79 Such ongoing anarchist resistance lead to the upsurge of a Third Wave, with the sorely understudied Manchurian Revolution of 1929–1931, the extreme isolation of which limited its impact to Chinese, Japanese, Manchurian, and especially Korean resistance. The Manchurian Revolution was unusual in that it was initially inserted from above, but quickly gained grassroots support because it was based on worker and community self-organisation.80 It demonstrated how the uplift of the working class through economic autonomy and education could combine seamlessly with a bottom-up system of decision-making and a militant defensive programme. In 1925, Korean anarchists helped form a “People’s Government” administration in the Shinmin Prefecture bordering on Korea, which helped democratise the prefecture. Subsequently, the Korean Anarchist Federation (KAF) militant Kim Jong-Jin, a close relative of the anarchist-sympathetic Korean Independence Army general Kim Jao-Jin, whose forces effectively controlled the Shinmin Prefecture, submitted an anarchist plan to the military command. It advocated the formation of voluntary rural co-operatives, self-managed by the peasantry, and a comprehensive education system for all, including adults. After some debate, and input from Yu Rim (the alias of Ko Baeck Seong), a founder of the Korean Anarchist Communist Federation (KACF), the general and his staff accepted the plan, and the anarchists were given the go-ahead for their plan.

In 1929, anarchist delegates from Hailun, Shihtowotze in the Chang Kwan Sai Ling Mountains, Sinanchen, Milshen, and other centres, also formed the Korean Anarchist Federation in Manchuria (KAF-M) at Hailin. The Shinmin Prefecture was transformed into the Korean People’s Association in Manchuria, a regional, libertarian socialist administrative structure, also known as the General League of Koreans (Hanjok Chongryong Haphoi) or HCH, which embraced a liberated territory of some two million people. This self-managed structure was comprised of delegates from each area and district, and organised around departments dealing with warfare, agriculture, education, finance, propaganda, youth, social health, and general affairs, the latter including public relations. Delegates at all levels were ordinary workers and peasants who earned a minimum wage, had no special privileges, and were subject to decisions taken by the organs that mandated them, including the co-operatives. Notwithstanding its bizarre origins from a meeting between the Kims, Yu, and the Army command, the HCH was based on free peasant collectives, mutual aid banks, an extensive primary and secondary schooling system, and a peasant army. The militia was initially drawn from the Army, but increasingly supplemented by fighters trained at local guerrilla schools. Again, we see the Bakuninist strategy of specific organisations, the KAF-M and the KAFC, operating under the aegis of a delegated civilian mass organisation based on free communes, the HCH, and defended by armed militia. In echo of the Zapatistas in the Mexican Revolution, the “Manchurians” operated almost exclusively in rural areas and relatively small towns. In Fukien province, southern China, which was under informal Japanese influence, situated as it is across the Formosa Strait, KAF-C members participated in the Chuan Yung People’s Training Centre, an initiative aimed at establishing an autonomous self-rule district in Fukien, emulating Shinmin. They were subsequently involved in attempts to form a peasant militia and rural communes in the area. But to the north, the Manchurian Revolution was destroyed by the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, and the KAF-M and KACF were forced to fight a rearguard retreat into southern China, where they continued the armed struggle against Imperial Japan alongside their Chinese comrades until Japan’s defeat in 1945.

However, it was the explosion of the running class war in Spain into full-throated revolution, taking place when the Fascist-oriented colonial military staged a coup d’état in 1936, that captured the attention of the whole world. Seen as a laboratory of virtually every known competing political tendency from anarchism to Fascism, the Spanish Revolution was in many ways the most compelling of the century. Detail on the Spanish Revolution of 1936–1939 is largely unnecessary because the events are so well known. For my purposes here, suffice it to say that the loosely-structured Makhnovist model of free communes and soviets, organically linked to revolutionary/anarcho-syndicalist unions (IWW, etc.), overseen by a mass class organisation (Congress of Peasants, Workers, and Insurgents), linked to specific anarchist organisations (Nabat, GAK, etc), and defended by affiliated or autonomous militia (RPAU and the Black Guards) was replicated. It was done in a tighter formation and a more continuous fashion in the cities of Catalonia, Aragon, and Valencia than had been the case in Ukraine, where the constantly shifting front-line had meant that Makhnovist urban administrations had few chances to establish themselves for long. The Spanish Revolution saw free communes more closely linked to the two-million-strong, anarcho-syndicalist National Confederation of Labour (CNT), which had declared itself for libertarian communism at its 1936 Zaragoza Congress. The CNT, in turn, was in formal alliance with the synthesist Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI), the Libertarian Youth Federation of Iberia (FIJL), and its Catalan-language corollary, the Libertarian Youth (JJLL). The CNT-FAI-FIJL and the free communes were defended by affiliated Confederal militia, such as the famous Durruti Column.81 Sadly, compromises and strategic blunders were made by reformists and opportunists in the anarchist ranks, who betrayed the class line by elevating the CNT-FAI to regional and then national office in the Republican state, accepting minority posts on the Councils of Aragon and Valencia when they were the overwhelming majority on the ground, and failing to implement the Zaragoza resolution on establishing a national Defence Council to federate all worker and peasant communes. Equally destructive were the technocrats in the FAI who attempted to turn it into a conventional political party, a seizure of the organisation made possible precisely because of its synthesist lack of internal coherence, and undermined the Revolution from within.82 Along with the earlier experiences of the handful of leading anarchists in Czechoslovakia, China, and Korea who tried to use the vehicle of the nation to achieve anarchist ends, the example of Spain clearly shows that internationalist anarchism and the interests of the global working class are totally at odds with nationalist government, however “revolutionary.” The outside support for the Francoist rebels of the pro-Fascist imperial powers, the betrayals of the Bolsheviks, and the extremely fragmented nature of the republican camp all led to Spain being recalled, incorrectly, as the swan-song of anarchism, a song soon drowned in the carnage of the Second World War. Still, the worker- and peasant-run fields and factories of Spain—the socialised tramways of Barcelona carried eight million passengers annually—provided the best-studied methods for the successful operation of an egalitarian society on a large scale, a lesson that humanity will not easily forget.

Although the defeat of the Manchurian and Spanish Revolutions was a great blow for the class, the Third Wave did not break until the end of the Second World War, when it peaked with armed anarchist resistance movements in France, China, Korea, Poland, Italy, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Francoist Spain, movements that were soon echoed in the anti-colonial struggles to come. Not only that, but numerous anarchist federations were formed in the closing phases of the World War II period and its immediate aftermath, as anarchists attempted to rebuild their political and trade union presence. According to Phillip Ruff, the Nabat was re-established in the Ukraine and staged an armed uprising in 1943, being commended by the 4th Guard of the Soviet Army for holding a bridgehead on the west bank of the Dnieper River. Its leader, school headmaster V.I. Us, was, however, jailed by the Soviet authorities for four years, though rehabilitated after Stalin’s death. Ukrainian anarchist partisans reportedly continued fighting as late as 1945, while within the Red Army occupying Germany and Austria immediately after the war, a secret Makhnovist organisation called the Kronstadt Accords (ZK) apparently operated.

In this period, along the lines of the Amsterdam model, anarchist-specific organisations suppressed by the war emerged in parallel to anarcho-/revolutionary syndicalist unions. For example, in France, the clandestine International Revolutionary Syndicalist Federation (FISR) emerged in 1943, leading to the establishment of the National Confederation of Labour (CNT) in 1945, alongside and within which operated the Francophone Anarchist Federation (FAF), which was established the same year. It is possible that the 17,500 Senegalese who defected in 1948 from the French Marxist CGT, joined the anarcho-syndicalist CNT which had a far more progressive stance towards national independence for the colonial world—but I am still researching this. The Federation of Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria (FAKB) and its unions resurfaced. In Italy, the Federation of Italian Anarchist Communists (FdCAI) was founded in 1944 and had some influence on the anarchist tendency in the new General Italian Workers’ Federation (CGIL). The Anarchist Federation of Britain (AFB) was founded in 1945 and worked alongside the new Syndicalist Workers’ Federation (SWF). The AFB did not survive the Third Wave, and another regional federation was only rebuilt during the Fourth Wave in 1967, alongside an equally short-lived Anarchist Communist Federation (ACF) the following year. The ACF seeded a lineage in the 1970s, however, which resulted in the refounding of the ACF in 1986.83

The Japanese Anarchist Federation (JAF) was founded clandestinely under US military occupation in 1945 with about 200 members, followed the next year by the syndicalist Federation of Free Labour Unions (FFLU) and Conference of Labour Unions (CLU).84 The JAF split in 1951, with the “pure” anarchists founding the Japanese Anarchist Club (JAC) and the anarcho-syndicalists forming the Anarchist Federation which in 1955 was renamed the JAF again. It affiliated to the IFA but collapsed in 1968, being replaced by the Black Front Society (KSS) in 1970, followed by a Libertarian Socialist Council (LSC). In 1983, the anarcho-syndicalist Workers’ Solidarity Movement (RRU) was established, becoming for a while the Japanese section of the IWA. In 1988, a new Anarchist Federation was established in Japan. In 1992, the Workers’ Solidarity (RR) anarcho-syndicalist network split from the RRU, which turned towards ultra-left communism and left the IWA.

New formations also emerged in regions where organised anarchism had been absent for some time: the Federation of Libertarian Socialists (FFS) was established in Germany in 1947; built by the likes of veteran anti-militarist, anarcho-syndicalist, and journalist Augustin Souchy (1892–1984)—who was active in Germany, then in exile in Revolutionary Spain, jailed in France, then active in Mexico, and who wrote probably the best first-hand critique of looming authoritarianism in Revolutionary Cuba in 1960—the FFS survived into the 1950s. In 1977, an anarcho-syndicalist Free Workers’ Union (FAU) was established in Germany in echo of the old FAUD; still active today, it is affiliated to the IWA and is online at www.fau.org. The North African Libertarian Movement (MLNA), which came to embrace Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, was founded in 1947.85 The revolutionary syndicalist Independent League of Trade Unions (OVB) was founded in the Netherlands in 1948; the OVB, which is online at www.ovbvakbond.nl, was based among dock-workers and fishermen at The Hague, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam; it split in 1988 with the anarcho-syndicalists leaving to form the Free Union (VB), which is online at www.vrijebond.nl. The collapse of Spain also sent an anarchist diaspora out into the world, from North Africa to Chile. Its greatest impact was felt in France, where militants fought in the resistance against the Nazis, in Cuba, where the movement experienced a dramatic growth-spurt, coming to dominate both the “official” and the underground union federations after World War II, and in Mexico and Venezuela where the exile presence was large enough to form two significant autonomous anarcho-syndicalist formations: the General Delegation of the CNT (CNT-DG) in Mexico in 1942, which co-ordinated CNT exile Sub-Delegations across Latin America, and the Venezuelan Regional Workers’ Federation (FORV) in 1944.86

Another strongpoint of anarcho-syndicalist organising in the immediate post-war period, usually overlooked, may have existed in China, where the movement reportedly maintained a minority trade union presence of only about 10,000–strong in Guangzhou and Shanghai together, under the difficult conditions of conflict between the nationalists and the Bolsheviks, but this is hard to verify. In Korea, the defeat of Japan lead to a rapid reorganisation of anarchist forces, as the KAF-C, its youth wing, the KYFSC, affiliates in the Eastern Anarchist Federation, as well as many other “black societies,” combined to create the huge Federation of Free Society Builders (FFSB).87 A strong libertarian reformist tendency also developed, with the entry of a few key members of the KACF, such as Yu Rim, and of the Korean Revolutionist Federation (KRF), into the five-party, left-wing Korean Provisional Government (formed in exile in 1919) from 1940 until about 1946. American and Russian occupational forces allowed this shadow government no access to power and supplanted it with their own proxy governments in 1948.

In 1948, at a pan-European anarchist conference in Paris, the Anarchist International Relations Commission (CRIA) was established with the aim of maintaining ties between the dispersed, rather battered, but still vibrant, post-war anarchist movement. CRIA established a sister organisation in Latin America, the Montevideo-based Continental Commission of Anarchist Relations (CCRA). The CRIA/CCRA saw itself as continuing the work of the 1907–1915 Amsterdam International and maintained a network of correspondence between anarchist organisations, journals, and individual militants in Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Bolivia, Brazil, Britain, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, France, Germany, Guatemala, India, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Morocco, the Netherlands, Panama, Peru, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Tunisia, Uruguay, the United States, Venezuela, and Yugoslavia. The CRIA/CCRA held its first congress in Paris in 1949, and, at its congress in London in 1958, it joined with the Provisional Secretariat on International Relations (SPIRA) and was transformed into the Anarchist International Commission (CIA), which survived until about 1960.88

The Durrutist and neo-Makhnovist response: The “Revolutionary Junta” Pushes for a Fresh Revolution

During the Spanish Revolution, at the height of the Third Wave, anarchists faced the same question raised in the 1920s by the Platform: how to organise in a free, yet effective, manner. Aware that the communists and reformists within the trade unions were selling out the revolution, a militant group of anarchists formed in 1937 to maintain the revolutionary hard line. The Friends of Durruti (AD) were named after the brilliant Spanish anarchist railway worker and guerrilla fighter, Buenaventura Durruti, who died defending the capital of Madrid against the Francoist forces in 1936. The AD was founded by rank-and-file CNT militants, key anarchist hardliners, and anarchist militia, in particular from the famous Durruti Column and the Iron Column. They opposed the “revolutionary” state’s order to turn the militia into an ordinary authoritarian army, with class divisions and a murderous regime of punishment.

In 1938, encouraged by the Spanish Communist Party, the counter revolution was in full swing, in the rear of and at the revolutionary front. The AD published Towards a Fresh Revolution, a strategic document that critiqued the reformist tendency within the CNT, one which had lead to confederated collaboration with bourgeois, nationalist, conservative, and Bolshevik forces in the Republican government. The document called for a “revolutionary junta” (meaning a “council” or “soviet”) to maintain the revolutionary character of the war by means of the anarchist/syndicalist militia, and for the economy to be placed entirely in the hands of the syndicates—the revolutionary anarcho-syndicalist unions which made up the base of the CNT. It was, in effect, a call by the organised revolutionary working class under arms to dissolve the bourgeois Republican government and replace it with a decentralised militant counter-power structure. In the document, the AD also demanded the seizure of all arms and financial reserves by the workers; the total socialisation of the economy and food distribution; a refusal to collaborate with any bourgeois groups; the equalisation of all pay; working class solidarity; and a refusal to sign for peace with foreign bourgeois powers.

Like the Makhnovist Platform, the AD manifesto was also labelled vanguardist and authoritarian, this time because of a misunderstanding, mostly among English-speakers, of what was meant by the revolutionary junta. In the AD’s usage, junta did not have the connotations of a ruling military clique that the term carries in English. It was not to be an “anarchist dictatorship,” supplanting the bourgeois government with an anarchist one. Its task was merely to co-ordinate the war effort and make sure that the war did not defer or dismantle revolutionary gains. The rest of the revolution was to be left in civilian worker hands.

In 1945, the Bulgarian platformist FAKB, founded in 1919, called a congress at Knegevo, in the capital city of Sofia, to discuss the repression of the anarchist/syndicalist movement by the Fatherland Front government. This government had been installed by the Red Army and consisted of Communist Party and Agrarian Union members and fascist Zveno officers, involved in the 1934 fascist putsch. However, all 90 delegates were arrested by Communist militia and put into forced labour camps. Anarchist locals were forcibly shut down and the revived FAKB newspaper Rabotnicheska Misal (Workers’ Thought) was forced to suspend publication after only eight issues. It reappeared briefly during Fatherland Front-rigged elections, held in 1945 under American and British pressure, surging from a circulation of 7,000 to 60,000, before being banned again. More than 1,000 FAKB militants were sent to concentration camps and the next annual congress of the FAKB had to take place clandestinely in 1946.

Despite the repression, in 1945, the FAKB was able to issue a key platformist strategic document. The Platform of the Federation of Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria argued for an anarchist/libertarian communist future order. While rejecting the traditional political party as “sterile and ineffective,” and “unable to respond to the goals and the immediate tasks and to the interests of the workers,” it advocated for anarcho-/revolutionary syndicalist unions, cooperatives, and cultural and special organisations (like those for youth and women), as well as a specifically anarchist political group along the lines of the original 1927 Platform:

It is above all necessary for the partisans of anarchist communism to be organised in an anarchist communist ideological organisation. The tasks of these organisations are: to develop, realise and spread anarchist communist ideas; to study the vital present-day questions affecting the daily lives of the working masses and the problems of the social reconstruction; the multifaceted struggle for the defence of our social ideal and the cause of working people; to participate in the creation of groups of workers on the level of production, profession, exchange and consumption, culture and education, and all other organisations that can be useful in the preparation for the social reconstruction; armed participation in every revolutionary insurrection; the preparation for and organisation of these events; the use of every means which can bring on the social revolution. Anarchist communist ideological organisations are absolutely indispensable in the full realisation of anarchist communism both before the revolution and after.

According to this neo-Makhnovist manifesto, such anarchist political/ideological organisations were to be federated across a given territory, “co-ordinated by the federal secretariat”—similar to the Durrutist “revolutionary junta”—but the “local organisation” was to remain the basic policy-making unit, and both local and federal secretariats to be “merely liaison and executive bodies with no power” beyond executing the decisions of the locals or federation of locals. The FAKB Platform emphasised the ideological unity of such organisations, stating that only committed anarchist communists could be members, and that decision-making must be by consensus, achieved by both persuasion and practical demonstration, rather than by majority vote (the latter being the method applicable to anarcho-/revolutionary syndicalist and other forms of organisation, with allowances made for dissenting minorities). Anarchist militants, so organised, would participate directly in both syndicalist unions and mainstream unions, arguing their positions, defending the immediate interests of the class, and learning how to control production in preparation for the social revolution. Militants would also participate directly in co-operatives, “bringing to them the spirit of solidarity and of mutual aid against the spirit of the party and bureaucracy”—and in cultural and special-interest organisations which support the anarchist communist idea and the syndicalist organisations. According to the FAKB Platform, all such organisations would relate to each other on the basis of “reciprocal dependence” and “ideological communality.”