THE MODEL of Conscious Experience you learned about in the First Interlude introduced the ideas of attention and peripheral awareness. While that model was helpful for working through the first four Stages, it was incomplete. As you progress in your practice, you’ll need more detailed models of the mind to help make sense of your new experiences. Here, we present the Moments of Consciousness model. It builds on what you’ve already learned, recasting many of the concepts already used.

This model is drawn from the Theravada Buddhist Abhidhamma, and includes some elaborations and expansions by a later Buddhist school known as the Yogācāra. This Interlude and the next take ideas about the mind from both these sources and explore them using modern terminology and a more science-based framework.

Keep in mind that this model is intended to help you understand both your own experiences and the meditation instructions better. Don’t bother with trying to decide whether the description is literally true or not. As your meditation skills mature, you’ll have plenty of time to decide what you think, based on your own experiences. What’s more important is that the model is useful for making sense of and working more effectively in your practice.

Our everyday conscious experience of the world—the thoughts and sensations that arise and pass away—appear to flow together seamlessly from one moment to the next. However, according to the Moments of Consciousness model, this is an illusion. If we observed closely enough, we would find that experience is actually divided into individual moments of consciousness. These conscious “mind moments” occur one at a time, in much the same way that a motion picture film is actually divided into separate frames. Because the frames pass so quickly and are so numerous, motion on the film seems fluid. Similarly, these discrete moments of consciousness are so brief and numerous that they seem to form one continuous and uninterrupted stream of consciousness.

If you observed closely enough, you’d find that experience is actually divided into individual moments of consciousness.

According to this model, consciousness is a series of discrete events rather than continuous, because we can only be conscious of information coming from one sense organ at a time. Moments of seeing are distinct from moments of hearing, moments of smelling from moments of touch, and so on. Therefore, each is a separate mental event with its own unique content. Moments of visual experience can be interspersed with moments of auditory, tactile, mental, and other sensory experience, but no two can happen at the same time. For example, a moment of visual consciousness must end before you can have a thought (a moment of mental consciousness) about what you’ve just seen. It is only because these different moments replace each other so quickly that seeing, hearing, thinking, and so forth all seem to happen at the same time.

The Moments of Consciousness model posits that, within each of these moments, nothing changes. They are truly like freeze-frames. Even our experience of watching something move is the result of many separate moments of visual consciousness, one rapidly following the next.1 Therefore, all conscious experience, without exception, consists of individual, brief moments, each containing a single, static chunk of information. In that sense, we can say that each mind moment provides only a single “object” of consciousness. Because moments of consciousness coming from different sense organs contain such different information, consciousness is less like a film, in which every frame is similar to the last, and more like a string of differently colored beads.2

Within each moment of consciousness, nothing changes—they are like freeze-frames. Your experience of seeing movement is many separate moments of visual consciousness, rapidly following each other.

While this model is quite different from how we usually think about consciousness, it’s not just a nice theory someone thought up. The basic premise of distinct moments of consciousness arising and passing away in sequence is based on the actual meditation experiences of advanced practitioners from across a broad range of traditions.3 It’s an experience that the composers of the Abhidhamma, who formulated this model, either had firsthand, or learned about from other advanced meditators. It’s also an experience you yourself will have in the later Stages. Yet, long before you do, this model will help you, just as it has helped other practitioners for over two millennia.

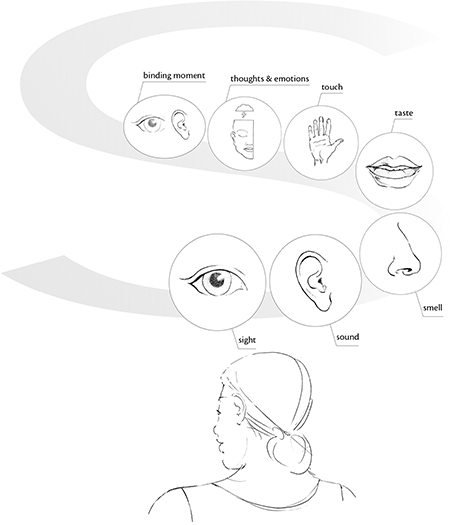

In this model, the different types of moments of consciousness vary according to which of our senses provides the “object” in a given moment. In all, there are seven kinds of moments. The first five are obvious, since they correspond to the physical senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. The sixth category, maybe less obvious, is called the mind sense,4 meaning it includes mental objects like thoughts and emotions. Finally, there is a seventh type of consciousness, called binding consciousness, that integrates the information provided by the other senses. Let’s take a closer look at these different kinds of moments of consciousness.

Figure 27. In all, there are seven kinds of moments of consciousness. The first five correspond to the physical senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. The sixth category is called the mind sense, meaning it includes mental objects like thoughts and emotions. Finally, there is a seventh type of consciousness, called binding consciousness, that integrates the information provided by the other senses.

Of the five physical senses, the last on the list, “touch,” properly known as “somatic sensation,” is more complicated and diverse than the first four. It would be more accurate to say that the somatosensory category is actually comprised of many different senses. For example, there’s the category of skin sensations, which includes not just touch, but also pressure, movement, and vibration. There’s a separate category that includes things like temperature, pain, tickle, itch, and some sexual sensations. Then, there’s what’s called “proprioception,” the sense that informs us about the position, location, and movement of the parts of our body. Sensations of muscle tension, deep visceral sensations, and the physical sensations we associate with emotions each constitute other distinct categories of sense experience. Finally, the sensations of acceleration, rotation, balance, and gravity make up yet another category completely overlooked by the classical “five senses.” From a physiological perspective, each of these somatosensory categories is actually a unique sense unto itself, served by its own subsystem within the central nervous system. According to the Moments of Consciousness model, information from no two of these somatic sense categories can occupy the same moment of consciousness, either; just as we can’t see an object and hear a sound at the same time, we can’t, for example, sense motion and feel pain at the same time. So there are, in fact, more than five different kinds of physical senses.

It’s the same situation with the mind sense. It was traditionally treated as a single “sense” through which we become conscious of “mental objects.” Yet in reality, memories, emotions, and abstract thoughts, for example, each derive from distinctly different brain processes, and each provides a unique kind of information. Therefore, information from two different mental categories can’t share the same moment of consciousness, either; you can’t solve an algebra problem while, at the same time, remembering a childhood pet. We have to recognize that both the mind sense and the somatic sense are actually blanket labels encompassing many sense categories, each conveying its own unique kind of information. However, for the sake of simplicity, we will ignore these diverse senses and just refer to six basic categories of moments of consciousness corresponding to the sight, smell, taste, touch, hearing, and mental senses.5

However, if the contents of one moment are gone before the next arises, how do these distinct kinds of information ever get integrated with each other in conscious experience? How do we ever put it all together so we can understand what’s actually happening? The answer is that the content of many separate moments, provided by the first six sense categories, get briefly stored in a kind of “working” memory, where they are combined and integrated with each other. Then the “product” of this integration is projected into consciousness as yet another distinct type of mind moment, the combining or binding moment of consciousness.6

Consider the experience of hearing someone speak. When the contents from visual and auditory moments of consciousness have been combined, binding moments are produced. These binding moments match the sounds we hear to the specific objects we see in our visual field. In other words, our subjective experience is hearing words come from a particular person’s mouth. This kind of mental activity also occurs when we watch a movie: notice how your mind automatically attributes particular voices to specific characters, when in fact the sound originates from speakers in the theater walls. The sound may even be coming from behind you! And, of course, the reason ventriloquists can fool us is because binding moments don’t always put the information together in an accurate way.

Figure 28. If the contents of one moment are gone before the next arises, how do we ever put it all together so we can understand what’s actually happening? The content of separate moments gets briefly stored in “working” memory, where the moments are combined and integrated with each other. The “product” is projected into consciousness as a “binding moment” of consciousness.

Binding moments are integrated perceptions combining information from the other six senses to produce complex representations of what’s happening within and around us. They are regarded as a seventh kind of moment of consciousness, distinct from the other six. Therefore, the seven different kinds of moments of consciousness are: sight, sound, smell, taste, somatosensory, and mental, plus the binding moment.

Recall from the First Interlude that all conscious experience gets filtered through either attention or awareness. They form two distinct ways of knowing the world. But how do attention and awareness fit into this more in-depth model? If all conscious experience consists entirely of the seven kinds of mind moments, what place is there for attention and awareness? It’s simple: any moment of consciousness—whether it’s a moment of seeing, hearing, thinking, etc.—takes the form of either a moment of attention, or a moment of peripheral awareness. Consider a moment of seeing. It could be either a moment of seeing as part of attention, or a moment of seeing as part of peripheral awareness. These are the two options. If it’s a moment of awareness, it will be broad, inclusive, and holistic—regardless of which of the seven categories it belongs to. A moment of attention, on the other hand, will isolate one particular aspect of experience to focus on.

Any moment of consciousness can be either a moment of attention or a moment of peripheral awareness. Moments of awareness contain many objects; moments of attention contain only a few.

If we examine moments of attention and moments of awareness a bit closer, we see two major differences. First, moments of awareness can contain many objects, while moments of attention contain only a few. Second, the content of moments of awareness undergoes relatively little mental processing, while the content of moments of attention is subject to much more in-depth processing. Of course, these two are not so neatly divided experientially. But understanding these differences will help you appreciate how each functions and their different purposes in organizing subjective reality.