The 1888 edition of Housekeeping in the Blue Grass.

CHAPTER TWO

Post–Civil War Cookbooks

In the introduction to The Kentucky Housewife: A Collection of Recipes for Cooking, Mrs. Peter A. White includes the intriguing but cryptic statement that her cookbook will help “home life in Kentucky under the new regime” (1885, 3).1 Although she provides no explanation, I think the “new regime” refers to the dramatic changes occurring in the white, upper-class households of the region after the freeing of enslaved persons and other stresses caused by the Civil War. These households had fewer staff after the war. They lost not only the physical help but also the knowledge of the formerly enslaved women, gained over years of service. One result was an increase in the number of cookbooks published during this period. John Egerton, speaking of the South in general, expresses the situation clearly: “One of the most fascinating and ironic indicators of the pervasiveness of this social pattern was the spate of post-Civil War cookbooks aimed at white women who found themselves quite literally help-less after the Civil War” (1993, 16). Toni Tipton-Martin’s words resonate with Egerton’s, as she states in the introduction to a reprint of The Blue Grass Cook Book, “the nation was in the throes of an entirely restructured social order.” She goes on: “Black servants fled the hard and thankless work in Southern households for better job opportunities in the promised land of the North” (Tipton-Martin 2005, xxv). More and more, upper-class housewives were on their own. Culturally, the community’s store of culinary knowledge was diminished with the loss of African American staff who understood both recipes and cooking techniques. According to Tipton-Martin, “Cookbooks appeared in record numbers,” and “most of them appealed in one way or another to the emotional needs of frustrated housewives who had lost their help mates” (ibid.). This may have increased the need and hence the market for cookbooks. As Bourbon County native Nannie Talbot Johnson wrote in the early pages of What to Cook and How to Cook It, “This is indeed a day of cookbooks” (1899, 3).

In addition to these important social changes, there were substantial improvements in cooking technology. At the heart of these innovations was the increased availability of mass-produced and affordable wood- or coal-fired cookstoves, which had an almost revolutionary impact on food preparation (see O’Neill 2004; Groft 2005; Brewer 2000). Hearth cooking became uncommon, and cookbooks like Mrs. Bryan’s The Kentucky Housewife fell out of favor, replaced by those that focused on woodstove cooking (see Fowler 2008). There were also changes in the design of pots and pans and food storage equipment. Another important advance was the advent of branded packaged goods and their inclusion in cookbooks from this period.

The starting point of our discussion of this era is an important central Kentucky charity cookbook, Housekeeping in the Blue Grass, produced by the Ladies of the Presbyterian Church of Paris, Kentucky, and first published in 1875. There were numerous (at least five) editions of this book; it was apparently published as late as 1905 with the same title. It seems that recipes in the new editions were treated as addendums, rather than making pervasive changes in the text. This cookbook was compiled, published, and sold by the Missionary Society to benefit the church. The preface says, “It was suggested, after mature consideration of ways and means, that we might not only greatly increase our funds, but also contribute to the convenience and pleasure of housekeepers generally, by publishing a good receipt book” (Presbyterian Church 1875, v). Before discussing this cookbook and its contents, I examine the early history of American charity cookbooks.

The 1888 edition of Housekeeping in the Blue Grass.

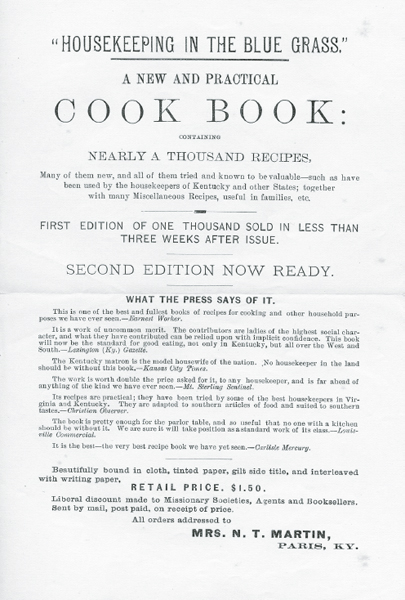

Flyer advertising the second edition of Housekeeping in the Blue Grass.

Charity Cookbooks

The production of fund-raising cookbooks by “women’s charitable organizations” began toward the end of the Civil War and accelerated dramatically in its aftermath (Longone 1997, 18). This occurred in both the North and the South. Initially these compilation projects were undertaken to raise money for veterans, widows, orphans, and other victims of the war. Margaret Cook’s bibliography of charitable cookbooks (1971) cites her view that A Poetical Cookbook by Maria J. Moss, published in 1864 in support of a “sanitary fair” in Philadelphia, was the first of its kind.2 By the mid-twentieth century there was a virtual flood of charity cookbooks, made possible by the marketing efforts of printing firms that had these books at the heart of their business plans. This trend continues to the present. Although it is not clear how many different cookbooks the women of the First Presbyterian Church of Paris produced between 1875 and today, their most recent, Feeding the Flock, was published in 2009 and pays homage to the original by reprinting its preface. As must be true of most regions in America, the fund-raising or charity cookbook is easily the most common type of cookbook published in Kentucky. Unfortunately, only a limited number of charity cookbooks can be found in libraries.

Charity cookbooks generally consist of recipes contributed from members of the community. For instance, the majority of recipes in Housekeeping in the Blue Grass are from Paris or Bourbon County (Paris is the county seat). Most of the rest of the contributors are from nearby communities in central Kentucky, and a handful come from other adjacent states. I list seven charity cookbooks published before 1900 in the bibliography—all of them church produced in Paris, Maysville, Louisville, Bowling Green, or Owensboro. The denominational breadth is quite narrow, being limited to mainline Protestant churches: Presbyterian, Methodist, Christian, and Baptist. The first cookbook from a Pentecostal Protestant church was produced more than ninety years later.

Because cookbooks of this type are group efforts, one could call them committee cookbooks. As a result, they tend to lack a clear culinary voice—for example, the formatting of recipes can vary. Charity cookbooks produced by the Junior League and similar efforts that appeared later in the twentieth century are exceptions, as they are produced with considerable editorial discipline.

Although they make interesting reading, these early charity cookbooks would require considerable adaptation if a twenty-first-century cook wanted to use the recipes. They tend to have very limited descriptions of procedures, with no specific times and temperatures. In a few cases I have found recipes consisting only of the word take and an ingredients list. Take is the right term. Recipe is derived from the imperative form of the Latin verb “to take.” Receipt, which is used interchangeably with recipe in early cookbooks, has the same meaning, but the etymology is Greek. Both terms were originally used for medical concoctions and were abbreviated Rx. The simple instruction “take” makes it quite clear that the users of these cookbooks had lots of skills and knew how to apply them, making detailed discussions of procedures superfluous. Illustrating this common assumption is a charming quote from Bettie Sue Broaddus, who contributed her mother’s recipe for hickory nut cake to Recipes Old and New: A Community Cookbook, published by the Estill County Historical and Genealogical Society in 2004. She writes, “Mama gave me no directions for mixing. She said, you know how to make a cake!” Nevertheless, Broaddus adds some instructions for the less experienced cook: “Just in case you are a beginner: Cream butter and sugar together. Add eggs, one at a time, mixing well after each one. Sift flour and baking powder together … ” (Estill County 2004, 81).

Others have made their own observations about the lack of instructions. In referring to a late-seventeenth-century English cookbook, irrepressible food writer M. F. K. Fisher points out that much technique is taken for granted in cookbooks: “In mixing the cake, the mace and nutmegs which have been prescribed are not mentioned again. Any idiot knows that they could be sifted along with the flour, and that of course they would be grated or powdered … but as a spoiled idiot-child of the twentieth century I want to be told” (1968, 6).

Following is an example of a “no instructions” recipe from Housekeeping in the Blue Grass. Only a few of its recipes are this simple.

White Sponge Cake (1875)

Ten eggs (whites only), one and a half tumblers of sugar, one tumbler (heaping) of flour, one teaspoonful cream of tartar, one teaspoonful essence of lemon. (Presbyterian Church 1875, 97)

A more typical and complex recipe is the one for Woodford pudding, which most assume is named for Woodford County, Kentucky. Recipes for Woodford pudding appear in other cookbooks more or less up to the present, and it is featured in John Egerton’s seminal Southern Food (1993). It is a jam-flavored baked pudding that is almost like a cake and is served with a sauce. Butterscotch and vanilla are popular flavors, and both the pudding itself and the sauce can be spiced up with bourbon. The following recipe, contributed by Mrs. Amos Turney Jr., is typical of the era, with its obsolete measure of teacups and no precise temperature or cooking time cited.

Woodford Pudding (1875)

Three eggs, one tea-cupful of sugar, one half tea-cupful of butter, one half tea-cupful of flour, one tea-cupful of jam or preserves, one teaspoonful of soda dissolved in three teaspoonfuls of sour milk. Cinnamon and nutmeg to taste. Mix all well together and bake slowly in a pudding pan. Serve with sauce. (Presbyterian Church 1875, 87)

The recipes in Housekeeping in the Blue Grass and other cookbooks of this era are sometimes vague about cooking times, most likely attributable to the variability of heat in woodstoves and assumptions about the cook’s knowledge. That said, a few recipes gear their instructions to the daily flow of work. Mrs. Morris Gass advises that one should put “a little flour” in her recipe for salt-rising bread at “about 11 o’clock” (Presbyterian Church 1875, 53). In a recipe for Sally Lunn, Mrs. J. Payne adjusts the timing of mixing the dough—combining flour, butter, eggs, salt, milk, and “good yeast”—based on the season: “Make it up about nine o’clock in the morning in winter, and eleven o’clock in summer; work it over about four o’clock, and make it in a round shape into pans and bake for seven o’clock tea” (ibid., 57).

In addition to Housekeeping in the Blue Grass, a number of other cookbooks were produced by groups of women as church fund-raisers. The New Kentucky Home Cook Book, published by the women’s group of the Methodist Episcopal Church South of Maysville, Kentucky, in 1884, was intended to help finance the construction of a parsonage. A somewhat expanded edition was published in 1885. Egerton comments, “This is a surprisingly broad and elegant assortment of culinary creations” (1993, 360). The following recipe for deviled eggs was contributed by Mrs. Robert Ficklin.

Deviled Eggs (1884)

Take one dozen hard-boiled eggs; when cold, remove the shell, and cut lengthwise; take out the yelks,3 and mash them well, with two tablespoons of butter, salt and pepper to taste, one heaping teaspoonful of mustard, and one level teaspoon of celery seed; moisten well with vinegar; replace the yelks, and press the two halves together. Place them in a dish, thin the rest of the yelks with more vinegar, and pour over the eggs. Grated cheese may be added to the filling, if desired. (Methodist Episcopal Church 1884, 184)

The Louisville Cookbook, Containing over Five Hundred Receipts, Some of Them Original, Many New, and All Thoroughly Tested, compiled by the First Christian Church Young Ladies’ Missionary Society of Louisville, uses the block or narrative format. It includes a recipe for Saratoga potatoes—the prototype for today’s potato chips. The recipe was submitted by Mrs. R. H. Wilson.

Saratoga Potatoes (1890)

Peel and slice very thin six large Irish potatoes. Let stand in salt water ten hours or over one night; dry on towel. Have beef suet hot in deep vessel, suet not less than 2 inches deep. When smoking hot, drop in about one-half of potatoes at one time. Fry very quickly; take out when light brown on a dish and sprinkle with salt while hot, when cool they will be dry. (First Christian Church 1890, 52–53)

Celebrity Cookbooks

The late nineteenth century gave rise to the first celebrity cookbooks. Mrs. John G. Carlisle’s Kentucky Cook Book, published in 1893, is the first cookbook listed in the bibliography to include the author’s name in the title. The question is, who is Mrs. John G. Carlisle? As I learned, she was the wife of a well-known politician from Kentucky. John G. Carlisle, a Democrat, was Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1883 to 1889 and then served as secretary of the treasury in the cabinet of his political ally President Grover Cleveland. An elementary school in Covington is named for him. Mrs. Carlisle’s compilation contains a few signed recipes, including one from Mrs. Grover Cleveland. The recipes use a mix of old and new measurements. Most are presented in a narrative format, but some consist of only lists of ingredients. Just one branded product, Cox’s gelatin, is mentioned, along with a few canned ingredients, including French peas, mushrooms, and pineapple. Mrs. Carlisle’s cookbook contains a number of baked and boiled pudding recipes, including the following.

Poor Man’s Pudding (1893)

One teacupful of shredded suet rubbed thoroughly into four cups of flour, two cups of New Orleans molasses, one cup of milk, into which put a teaspoonful of soda dissolved in hot water; one pound of currants washed and dried; one pound of raisins, stoned and chopped, one nutmeg, one large tablespoon of cinnamon. Put into a well floured pudding bag and boil for three hours. The water must be kept boiling hard or the pudding will be heavy. (Carlisle 1893, 121)

An interesting western Kentucky cookbook from this period is Mary Rochester Coombs’s Kentucky Cook Book. It was published in 1894 by a Bowling Green printer, C. M. Coombs, probably her husband. The recipes have “been gathered up by myself, not from doubtful sources, but from those of my friends who have had long experience in household duties” (Coombs 1894, i). Mrs. Coombs uses both the older block format and the more modern practice of providing a list of ingredients separate from the instructions. A number of the recipes are signed, usually without comment. In some cases, Mrs. Coombs mentions the location of the recipe contributor. For example, a potato soup recipe is signed by Mrs. Gillette, from a cooking class held in Louisville, and a recipe for gumbo soup is signed by Mrs. Frank Williams of New Orleans. One recipe is attributed to Miss Parloa; this is presumably the noted cookbook author Maria Parloa, whose Miss Parloa’s New Cookbook and Marketing Guide was first published in 1880. Most intriguing are the recipes for Kentucky corn dodgers and crackling bread signed by Mammy Charlotte, who, I believe, was an African American cook. If so, they could be the first published recipes attributed to an African American in a Kentucky cookbook. I don’t mean to slight Mrs. Coombs’s recipes, but I have included Mammy Charlotte’s recipe for corn dodgers here.

Kentucky Corn Dodgers (1894)

Make up one pint of meal, with one teaspoon of salt, a piece of lard the size of an egg, mix with warm water and sweet milk, (don’t make too thin as you cannot handle to make nice smooth pones) work the mixture well, with your hand until perfectly smooth, then make into pones, put on a hot baker that is well greased, cook in a hot oven, put on top shelf and let brown first, (as it prevents cracking) then place at the bottom and finish cooking. (Coombs 1894, 88)

The unsigned recipe for pumpkin bread following this one simply instructs the cook to add a teacup of stewed pumpkin to the corn dodger recipe.

Single-Author Cookbooks

Mrs. Peter A. White’s The Kentucky Housewife: A Collection of Recipes for Cooking, mentioned earlier in this chapter, is the first single-author cookbook from this era included here. There are others. Although Mrs. White’s book was published in Chicago, she was apparently raised in Lexington and wrote the book while a resident of Cincinnati.4 Unlike the charity cookbooks of the era, Mrs. White’s comprehensive volume demonstrates her sole authorship with its a uniform editorial voice. She presents the recipes in the modern format, starting with a list of ingredients. Mrs. Lincoln’s Boston Cook Book had first utilized that innovation the preceding year. Careful measurement is an important feature of the cookbook. Mrs. White’s introduction states: “Having always regarded a cookery book as a book for the kitchen, I have, in order to carry out my idea, not only been explicit in giving proportions, but have endeavored to express myself so simply that any cook who can read can take this book and be her own teacher” (1885, 8). The theme of “exact proportions” was featured in the advertising copy used by the publisher. That said, Mrs. White uses a diverse set of measures, mixing the modern and the obsolete. For example, on one page she uses the dessert spoon, cooking spoon, and salt spoon, as well as the familiar teaspoon. The book has an unusual publication history. The title was changed to The Kentucky Cookery Book: A Book for Housewives in 1891. It was apparently republished in 1903 as The Blue Grass Cook Book, with Genevieve Long listed as the author.

Mrs. Peter A. White’s The Kentucky Housewife.

Most of Mrs. White’s quick bread recipes include baking powder, but some make use of soda and cream of tartar or sour milk. These ingredients are usually accompanied by the admonition to “bake immediately.” Actual cooking times are sometimes included. For example, she gives the following cooking times for vegetables, which seem very long by today’s standards: “Peas and asparagus should be cooked one hour; beans, three hours; beets, two hours; turnips, two hours; potatoes, half an hour; cauliflower should be wrapped in a cloth and boiled two hours, and served with drawn butter” (White 1885, 59). Mrs. White’s recipe for okra soup uses a time-of-day cooking format.

Okra Soup (1885)

One chicken, or a small knuckle of veal,

Two quarts of clear water,

Six large tomatoes,

Four large onions,

One quart of okra,

One bunch of parsley

Salt and cayenne pepper to the taste,

One teaspoonful of summer savory,

Half a teaspoonful of powdered allspice.

Put on the chicken, or veal, in the water and let it boil up twice, skimming carefully until all of the grease is taken off; add the tomatoes, parsley, onions, summer savory, allspice, cayenne pepper and salt. Put this on at breakfast time; at 12 o’clock, put in a separate saucepan the quart of okra, cut up in thin slices. Boil for an hour, or until perfectly tender. Half an hour before dinner strain the soup and add the okra. This is for a 2 o’clock dinner; if for a later dinner put on the meat and vegetables at 1 o’clock and the okra at 5 o’clock. (White 1885, 58)

Product Placement

In cookbooks of this era we find the earliest mention of branded commercial products. For the most part, these consist of basic ingredients such as flavorings, leavens, and gelatin rather than true convenience foods. Housekeeping in the Blue Grass (1875) specifically mentions and endorses Cox gelatin, stating unequivocally that “Cox is best.” Also mentioned (and, by implication, endorsed) are Baker’s chocolate, Burrows’ ground mustard, Coleman’s mustard, Maillard’s vanilla chocolate, and Twin Brother’s yeast. Mrs. White mentions Cox’s gelatin, Fleischman’s yeast, and Coleman’s English mustard.

Packaging and the branding associated with it laid the foundation for advertising. The 1875 edition of Housekeeping in the Blue Grass includes more than thirty advertisements, some of which are for grocery stores. One advertisement for Dr. Price’s cream baking powder assures readers that Dr. Price’s product is “strictly pure” and that “it is not sold in bulk; buy it only in tin cans, securely labeled” (Presbyterian Church 1875, ii). Consumers seemed to fear that bulk ingredients could be easily adulterated or spoiled in other ways, so advertisements of this era often emphasized food purity and a clean production process.

In her history of American cookbooks, Carol Fisher (2006, 46) cites Miss Parloa’s New Cookbook and Marketing Guide (1880) as one of the first cookbooks to endorse products, although Housekeeping in the Blue Grass was published a few years earlier. Maria Parloa (who contributed a recipe to Mrs. Coombs’s cookbook) preceded Fannie Farmer as the principal of the famous Boston Cooking School, which actively engaged in product placement.

Cox’s gelatin was an early convenience food. It was originally imported from England but was ultimately manufactured in the United States as well. Although contemporary food writers tend to disparage processed food (and rightly so), the 1875 edition of Housekeeping in the Blue Grass contains a recipe for making jelly out of calves’ feet that clearly shows why cooks welcomed the availability of commercially produced gelatin (The Kentucky Housewife [Bryan 1839] has similar recipes).

Calves’ Foot Jelly (1875)

Split four feet and put the whole into a stewpan; pour one gallon of cold water over; boil till reduced to about one half then strain through a sieve, to remove the bones. When settled and cold, take off the grease from the surface and boil again with the following mixture; six eggs, whipped in a little water, two pounds of sugar, and the juice of four lemons; stir all well, removing the scum as it rises. When thoroughly skimmed, set by the fire and pour one pint of Madeira, or any other wine or liquor into it; filter through a flannel bag. (Presbyterian Church 1875, 125)

Calves’ feet are also used to make the jellies included on a festive menu originally created by Fannie Farmer and described by Chris Kimball in Fannie’s Last Super (2010). In the late nineteenth century, molded jellies were often served as desserts, and well-equipped kitchens had many decorative molds. The availability of gelatin converted an extraordinarily complex, messy, multistage task into a simple matter of ripping open a cardboard box (think Jell-O, which was widely available by 1904), pouring the contents into a pot of hot water, and stirring.

A few recipes in Housekeeping in the Blue Grass call for isinglass, another thickening agent that was used like gelatin. Isinglass is a powder prepared from the dried swim bladders of fish—originally sturgeon, but later cod, because it was much cheaper. (By the way, isinglass is still used to clarify beer.) The Kentucky Housewife also included some recipes made with isinglass. In fact, Mrs. Bryan made a big pitch for the superiority of Russian isinglass over the American variety. Housekeeping in the Blue Grass also includes a recipe or two that calls for Irish moss, which is derived from algae that is also the source of the thickener carrageenan. Carrageenan is still used in foods today; check the ingredients lists on various contemporary products, and sooner or later you will find carrageenan, but I have never seen isinglass listed. All the Housekeeping in the Blue Grass recipes that use these thickeners (calves’ foot jelly, manufactured gelatin, isinglass, and Irish moss) are sweet dishes.

Developments in Cookstoves

As stated earlier, cooking was typically done on a woodstove. Wood-fired cookstoves constructed of brick, with iron cooktops, were first developed in the 1730s. Improvements in these early patterns were achieved by an American-born physicist, Benjamin Thompson (aka Count Rumford). His work in the 1790s led to more fuel-efficient fireplaces and ovens. Cast-iron cookstoves became available by around 1830, although they were smaller than later versions. Wood-burning cast-iron cookstoves became more common after the Civil War and reached a high point in their development in the 1890s. By that time, gas cookstoves and a supply infrastructure were becoming available.

The big advantage was that wood- and coal-fired cookstoves used fuel far more efficiently than fireplaces (Brewer 1990, 35). Cookstoves also reduced the workload by raising the cooking pots off the hearth’s floor, making it much easier to move them from one source of heat to another. In addition, the fires of stoves required much less tending than fireplaces did. As a result, Housekeeping in the Blue Grass and the other cookbooks from this period contain fewer direct references to issues related to cooking fires compared with Mrs. Bryan’s hearth-focused cookbook.

A small woodstove at the McCreary County Museum in Sturges, 2013. (John van Willigen)

In this era there were hundreds of stove foundries in the United States, including in Kentucky. Some of the nineteenth-century Kentucky stove manufacturers were Baxter, Kyle and Fisher, Bridgeford, J. S. Lithgow, O. K. Stove, Progress, and Scanlon, all of Louisville; Bogenschutz in Covington; and Gladiator Stove in Russell in Greenup County. All the Kentucky stove manufacturers were located on the Ohio River. Woodstoves of this era were made of heavy cast iron, which increased transportation costs, so proximity to the river was an important consideration.5

Cast-iron stoves were often embellished with porcelain enameled surfaces, nickel trim, and other elaborate decorative elements. The heart of the woodstove was the firebox, which was usually situated at one side of the stove, with a door through which the fire could be stoked. Because the fire needed an adequate draft, there were adjustable vents to control the airflow into the firebox and a damper in the flue to control the heat and gases going up the chimney (the stove was connected to the chimney flue with a sheet-metal pipe). If the fire did not draw properly, the wood might smolder, and smoke could back up into the kitchen. If the stove drew too well, it would consume fuel too quickly and overheat.

Coal- and wood-burning stoves were superficially the same, but there were some differences. For one thing, wood could be burned in coal stoves, but coal could not be used in woodstoves. In coal stoves the firebox contained a grate on which the burning fuel rested. Typically, coal stoves came with a cast-iron handle that could be attached to this grate and used to shake the ashes into an ash box below. The ash box could be removed when it was full and dumped. Those that used coal would sift the ashes to recover unburned fuel. If woodstoves came with shaker grates, they were of a different design than those used in coal stoves.

The heat from the firebox was available for both the oven and the stove top. The stove top was flat and had two to eight removable round caps, usually eight inches in diameter. The caps were supported by a frame that could be lifted out, and each cap had a recess in which a cap lift er could be inserted. Although these caps might have resembled burners, they did not work that way. The entire surface of the stove top was hot, although the heat level varied with the distance from the firebox. A skilled cook knew how to reduce the heat by moving a pot away from the firebox. The recipe for “Clear Beef Soup” in Housekeeping in the Blue Grass addresses this situation: “After it has been well skimmed, set the pot on the back of the stove and let it boil gently six hours” (Presbyterian Church 1875, 2–3). This reminds one of putting something “on the back burner.”

Various options could be purchased with a basic stove. Many wood-stoves were equipped with hot water reservoirs and places to keep food warm. The optional hot water reservoir was often located adjacent to the oven, on the side opposite the firebox. It was typical for stoves to have metal shelves or cabinets above the stove top at eye level. There might also be cabinets underneath the oven, used to store pots and pans.

A typical morning ritual was to start the fire with a corncob soaked with coal oil (Slade 2004, 3) under a crisscross of kindling topped by the fuelwood itself. The men and boys of the household had the task of keeping the wood box full, which involved chopping wood into pieces of various sizes (including kindling), as well as harvesting the wood in the first place. Farms might have woodlots specifically for this purpose. This required axes, saws, chopping blocks, and other tools.

During the winter, the stove provided a welcome source of heat. In rural settings, it was common to care for lambs, typically born in the early spring, by the heat of the stove. Some cooks would hang green beans to dry on the wall in back of the stove. In summer, it was common practice to fire up the stove for breakfast in the relative cool of the morning, cook dinner early, and then let the fire die out. Supper would consist of leftovers from dinner. During canning season and on wash days, this was not an option, and kitchens could get very hot.

Cast-iron wood-burning stoves required a lot of maintenance (U.S. Department of Agriculture 1915, 44). Ashes had to be emptied daily and disposed of. Because the stove was made of assembled parts, they had to be sealed periodically with special fireproof material; in addition, the vent pipe, heat passages, and chimney had to be cleaned of soot and creosote from time to time to preserve efficiency and prevent fires. This was often a springtime task for the man of the house. The black stoves required the application of a graphite or carbon black–based polish to prevent rusting.

Woodstoves could be dangerous. While in use, they presented a burn risk to those in the confined space of the kitchen. Because the surface got extremely hot, children had to be watched constantly. The stove had to be placed carefully to avoid burning the floor and walls of the home. The ashes produced also presented a fire risk. Finally, a stove could expose the occupants of the house to carbon monoxide if there were leaks in the stove, flue, or chimney.

The heat available for cooking varied, based on the amount and variety of wood used, when the fueling occurred, the setting of the dampers, and a pot’s distance from the stove’s firebox. There was a lever that shunted heat to the oven for baking. In contrast to gas and electric stoves, there was no thermostat to control the oven temperature, although some woodstoves had a thermometer on the oven door. The problem of maintaining an even temperature in a wood-fired oven is illustrated by the following warning in the cake section of Housekeeping in the Blue Grass: “Never allow the heat to diminish while cake is baking or it will fall.” It also advises, “In baking cakes it is a good plan to fill a large pan with cold water and set it on the upper grate of the stove, to prevent them from burning or cooking too fast on top. Let it remain until the cakes are baked” (Presbyterian Church 1875, 96).

As mentioned in the preceding chapter, the transition from fireplaces to wood-burning (and gas and electric) stoves changed the practice of roasting meat. Originally, the meat was placed in front of the heat source, outside an oven, creating a dry cooking environment. With the woodstove, roasting involved cooking the meat in an enclosed space. Although the term roasting was still used, this was actually baking; nevertheless, people continued to refer to roasted chicken, pork, and beef (but, interestingly, baked ham). Baking created a moister atmosphere because, as the meat’s internal temperature rose, the moisture in the meat was released in the oven as steam. The drippings often spattered inside the oven, causing smoke that flavored the meat. Cooks attempted to enhance this process by starting with a high initial temperature to sear the meat and using prepared browning agents, such as Kitchen Bouquet, to brown the drippings and improve the flavor of the gravy. Kitchen Bouquet (currently manufac-tured by the Clorox Corporation) was first sold in 1880. Worcestershire sauce may have been used in the same way.

Today, some people still use wood-fired cookstoves for various reasons, including a desire to be self-reliant and live “off the grid.” There are firms that renovate and resell vintage woodstoves of various kinds. Wood- burning cast-iron cookstoves are still being manufactured in the twenty- first century; one of the oldest and largest cast-iron stove manufacturers is the United States Stove Company in South Pittsburgh, Tennessee. These firms make a variety of models—from very modern-looking woodstoves to those that resemble vintage stoves. In addition, some gas and electric stoves are manufactured to look like late-nineteenth-century woodstoves. There are also firms that convert old-time woodstoves to gas or electric for those who want to combine modern convenience with old-fashioned country charm.

This era brought considerable change in cooking technology, but it is important to keep in mind that the transition from fireplace to woodor coal-burning stove was quite gradual and occurred at different times in different places. And although they are not mentioned in the Kentucky cookbooks of the late nineteenth century, gas and kerosene stoves were already available.